Morphological Ontogeny and Life Cycle of Laboratory-Maintained Eremobelba eharai (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Identification of Eremobelba eharai

2.2. Morphology of Eremobelba eharai

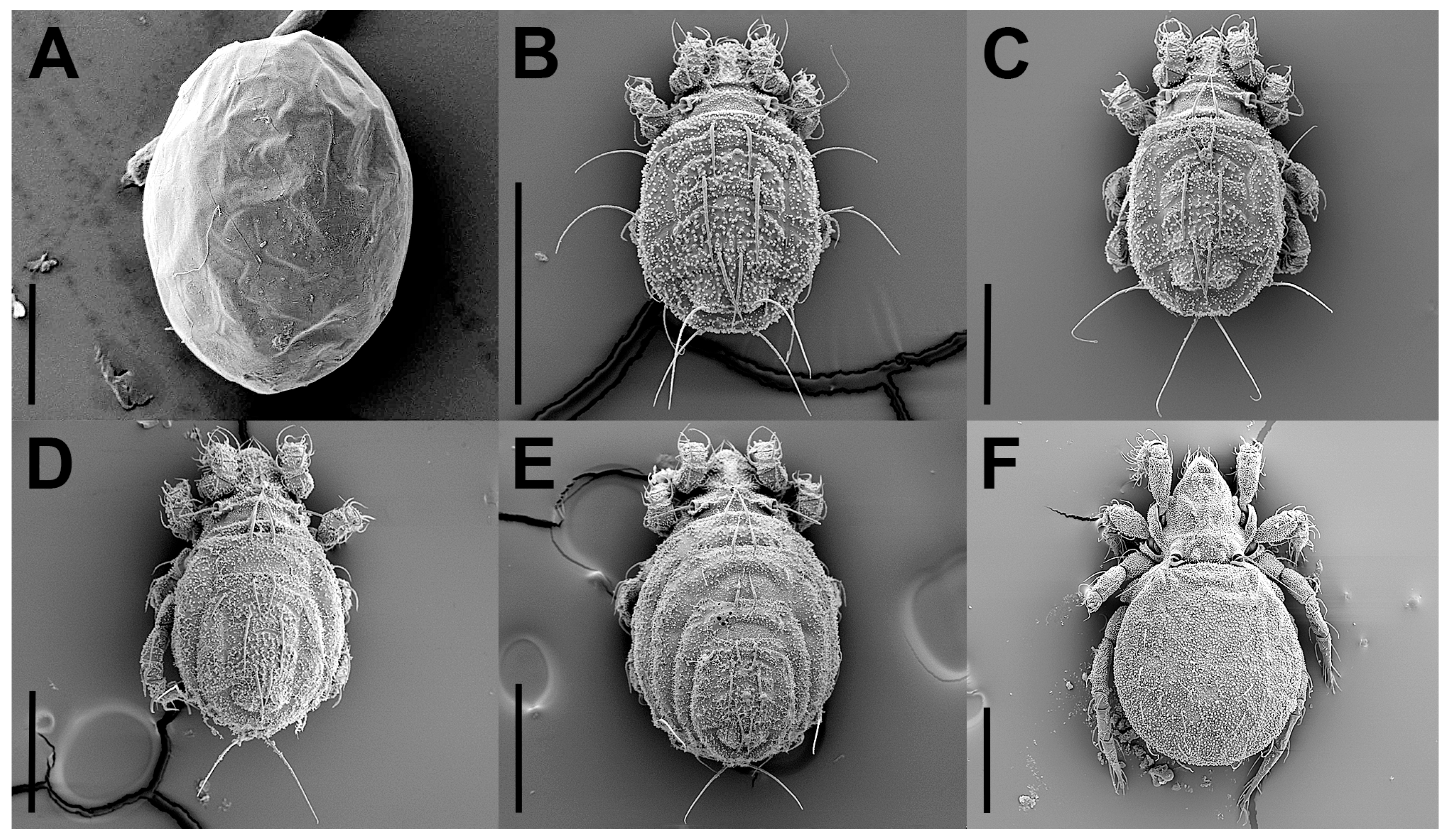

2.2.1. Observation, Documentation, and Terminology

2.2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Sample Preparation

2.3. Developmental Biology and Behavior of Eremobelba eharai

2.3.1. Living Mites Cultivation

2.3.2. Life Cycle Experiment and Developmental Monitoring

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.4. Preliminary Behavioral Observations

3. Results

3.1. Morphology and Ontogeny of Eremobelba eharai

3.1.1. Supplementary Diagnosis

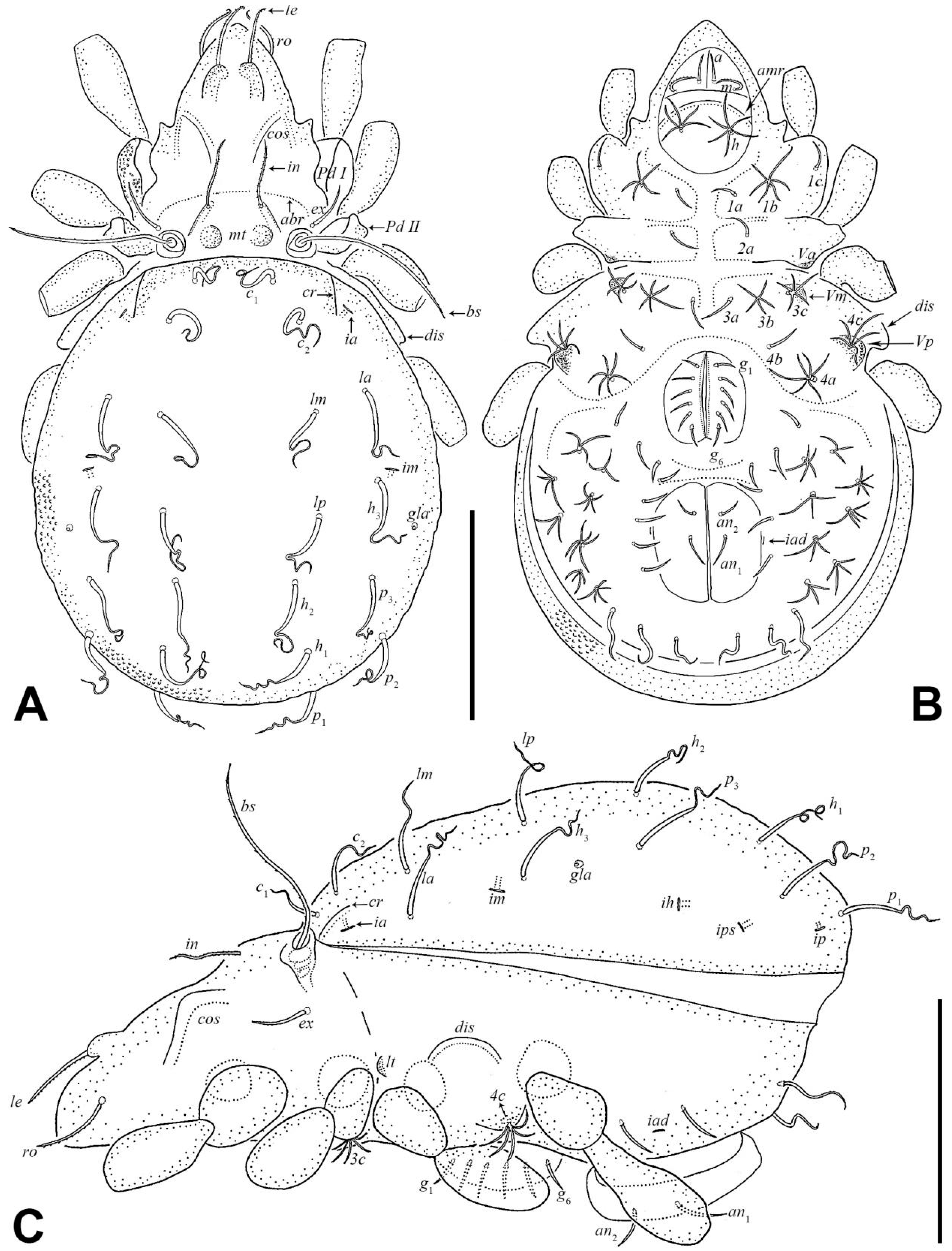

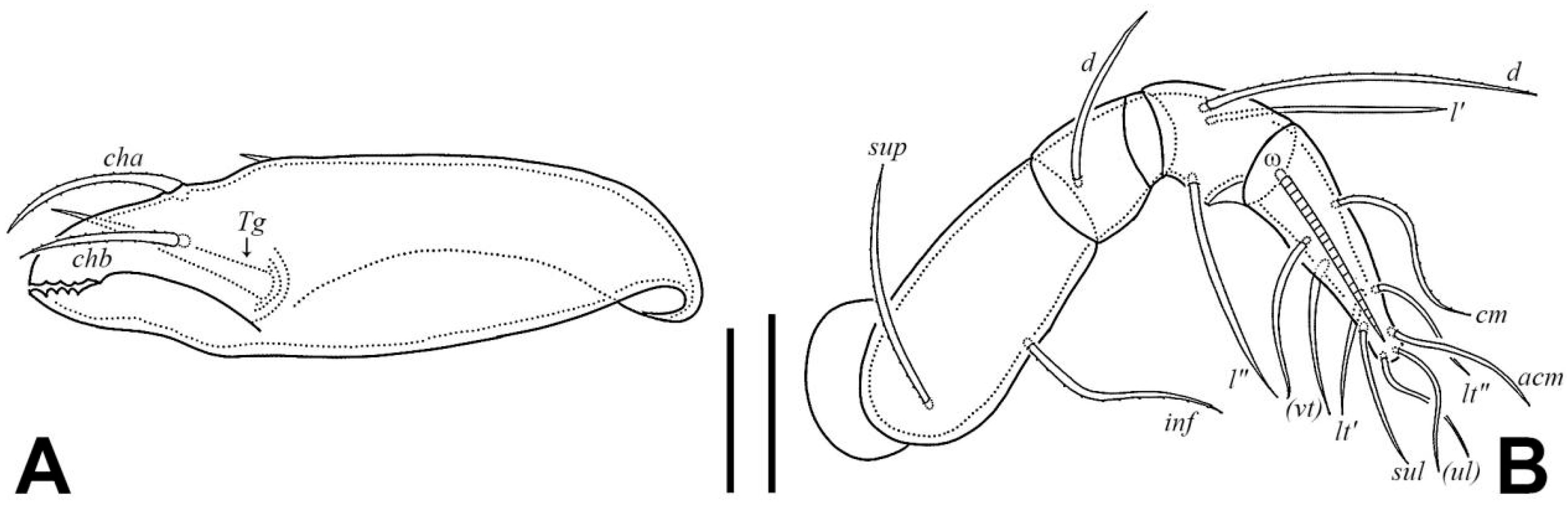

3.1.2. Redescription of Adult

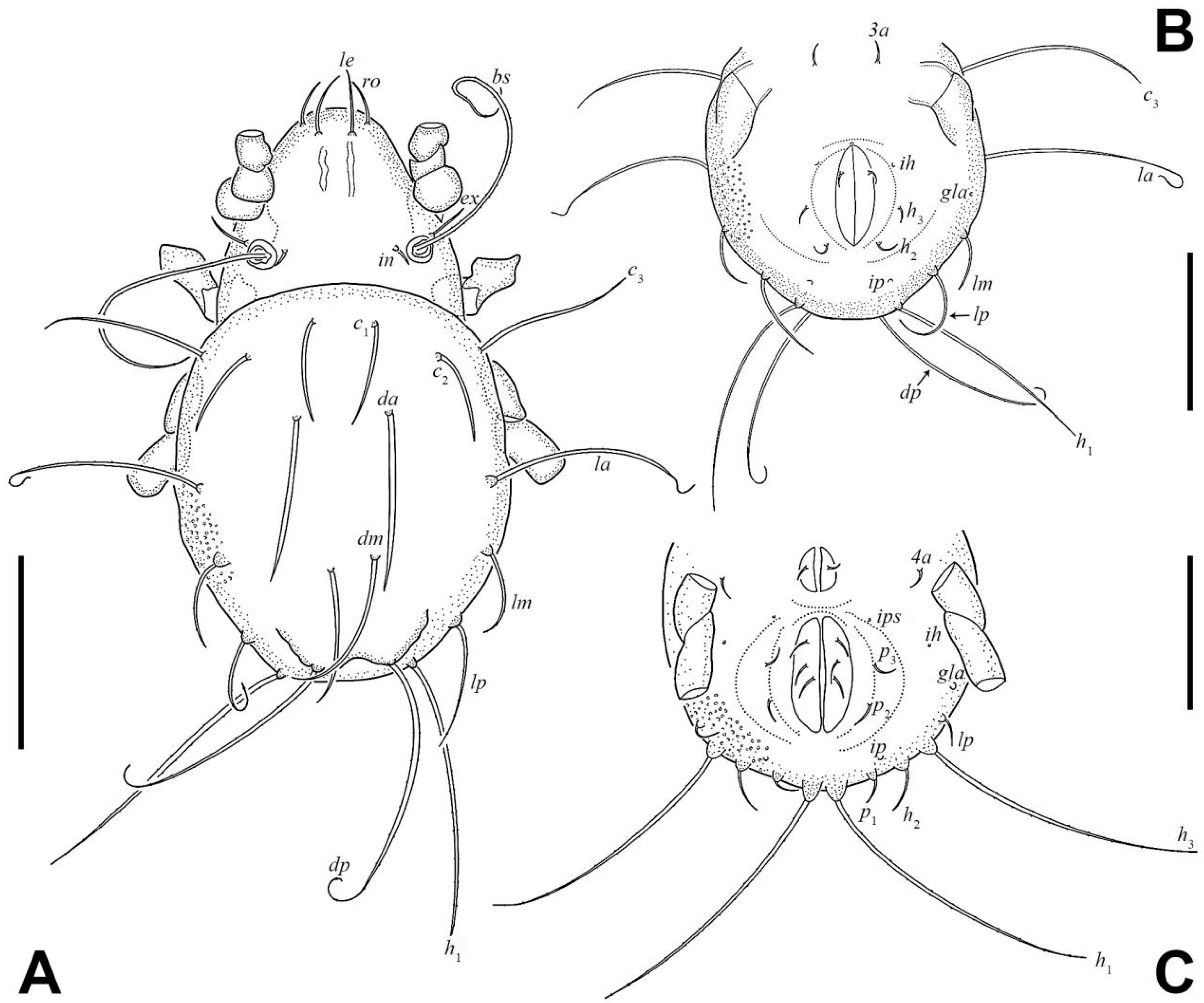

3.1.3. Description of Juveniles

3.1.4. Summary of Ontogenetic Transformations

3.1.5. Comparison of Morphological Ontogeny of Eremobelba eharai with E. geographica and E. gracilior

3.2. Developmental Stages and Behavior of Eremobelba eharai

3.2.1. Developmental Periods

3.2.2. Dark-Preference and Oviposition Behavior

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Variations of E. eharai Studied Herein Compared with Original Description

4.2. Development and Behavior of Eremobelba eharai

4.2.1. Life Cycle Duration and Behavioral Ecology

4.2.2. Preliminary Evidence for Parthenogenesis and Unresolved Questions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Koch, C.L. Deutschlands Crustaceen, Myriapoden und Arachniden; Part 3; F. Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.L. Deutschlands Crustaceen, Myriapoden und Arachniden; Part 29; F. Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.L. Deutschlands Crustaceen, Myriapoden und Arachniden; Part 30; F. Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.L. Deutschlands Crustaceen, Myriapoden und Arachniden; Part 31; F. Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1841. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.L. Deutschlands Crustaceen, Myriapoden und Arachniden; Part 32; F. Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1841. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.L. Deutschlands Crustaceen, Myriapoden und Arachniden; Part 38; F. Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1844. [Google Scholar]

- Seniczak, S. The Morphology of Juvenile Stages of Moss Mites of the Family Camisiidae (Acari: Oribatida). Zool. Anz. 1991, 227, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean, F. Essai de classification des Oribates (Acariens). Bull. Soc. Zool. Fr. 1953, 78, 421–446. [Google Scholar]

- Travé, J. Importance des stases immatures des oribates en systematique et en écologie. Acarologia 1964, 6, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.A.; Ermilov, S.G. Catalogue of juvenile instars of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida)—The next decade (2014–2023). Zootaxa 2024, 5419, 451–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfingstl, T.; Schatz, H. A survey of lifespans in Oribatida excluding Astigmata (Acari). Zoosymposia 2021, 20, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subías, L.S. Listado Sistemático, Sinonímico y Biogeográfico de Los Ácaros Oribátidos (Acariformes: Oribatida) del Mundo. Available online: http://bba.bioucm.es/cont/docs/RO_1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Maraun, M.; Thomas, T.; Fast, E.; Treibert, N.; Caruso, T.; Schaefer, I.; Lu, J.-Z.; Scheu, S. New perspectives on soil animal trophic ecology through the lens of C and N stable isotope ratios of oribatid mites. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 177, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J. Life history strategies of oribatid mites. In Biology of Oribatid Mites; Dindal, D.L., Ed.; SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.A. Evolutionary aspects of oribatid mite life histories and consequences for the origin of the Astigmata. In Ecological and Evolutionary Analyses of Life-History Patterns; Houck, M., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.A.; Behan-Pelletier, V.M. Suborder Oribatida. In A Manual of Acarology, 3rd ed.; Krantz, G.W., Walter, D.E., Eds.; Texas Tech University Press: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2009; pp. 430–564. [Google Scholar]

- Bulanova-Zachvatkina, E.M.; Shereef, G.M. Development and feeding of some oribatid mites. In Second Acarological Conference (Extended Abstracts); Naukova Dumka Press: Kiev, Ukraine, 1970; pp. 207–208. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shereef, G.M. Observations on oribatid mites in laboratory cultures. Acarologia 1972, 14, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Weigmann, G. Morphologie, Biogeographie und Ökologie einer in Zentraleuropa neuen Hornmilbe: Eremobelba geographica Berlese, 1908 (Acari, Oribatida, Eremobelbidae). Abh. Ber. Naturkundemus. Görlitz 2002, 74, 31−36. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, M. Investigations on the Oribatid Fauna of the Andes Mountains. I. The Argentine and Bolivia; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1958; Volume 10, pp. 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein, R. Soil Oribatei III. Studies on the development, biology, and ecology of Metabelba montana (Kulcz.) (Acarina: Belbidae) and Eremobelba nervosa n. sp. (Acarina: Eremaeidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1962, 55, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seniczak, S.; Ivan, O.; Kaczmarek, S.; Seniczak, A. Morphological ontogeny of Eremobelba geographica (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae), with comments on Eremobelba Berlese. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2021, 26, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermilov, S.G.; Khaustov, A.A. A contribution to the knowledge of oribatid mites (Acari, Oribatida) of Zanzibar. Acarina 2018, 26, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermilov, S.G. Redescription of Eremobelba gracilior Berlese, 1908 (Acari, Oribatida, Eremobelbidae). Acarina 2021, 29, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, R.A. A Review of F. Grandjean’s System of Leg-Chaetotaxy in the Oribatei and Its Application to the Damaeidae. In Biology of Oribatid Mites; Dindal, D.L., Ed.; State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner, A.; Schuster, R.; Smit, T.; Pollierer, M.M.; Schäffler, I.; Heethoff, M. Track the snack-olfactory cues shape foraging behaviour of decomposing soil mites (Oribatida). Pedobiologia 2018, 66, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, P. One new species in the genus Eremobelba (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae) from China. Entomotaxonomia 2017, 39, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, L. Species or morphological variation? A multivariate morphometric analysis of Afroleius simplex (Acari, Oribatida, Haplozetidae). In Trends in Acarology; Sabelis, M.W., Bruin, J., Eds.; Acarology Department, National Museum: Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2009; pp. 267–269. [Google Scholar]

- Pfingstl, T.; Baumann, J. Morphological diversification among island populations of intertidal mites (Fortuyniidae) from the Galapagos archipelago. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2017, 72, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindo, Z. Diversity of Peloppiidae (Oribatida) in North America. Acarologia 2018, 58, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seniczak, S.; Seniczak, A. Morphological Ontogeny and Ecology of a Common Peatland Mite, Nanhermannia coronata (Acari, Oribatida, Nanhermanniidae). Animals 2023, 13, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seniczak, S.; Seniczak, A.; Jordal, B.H. Morphological Ontogeny, Ecology, and Biogeography of Fuscozetes fuscipes (Acari, Oribatida, Ceratozetidae). Animals 2024, 14, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermilov, S.G.; Łochyńska, M. The influence of temperature on the development time of three oribatid mite species (Acari, Oribatida). North-West. J. Zool. 2008, 4, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Fajana, H.O.; Gainer, A.; Jegede, O.O.; Awuah, K.F.; Princz, J.I.; Owojori, O.J.; Siciliano, S.D. Oppia nitens C.L. Koch, 1836 (Acari: Oribatida): Current Status of Its Bionomics and Relevance as a Model Invertebrate in Soil Ecotoxicology. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 2593–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heethoff, M.; Laumann, M.; Bergmann, P. Adding to the reproductive biology of the parthenogenetic oribatid mite Archegozetes longisetosus (Acari, Oribatida, Trhypochthoniidae). Turk. J. Zool. 2007, 31, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Krumpálová, Z.; Štipčáková, L.; Petrovičová, K.; Ľuptáčik, P. Influence of plants on soil mites (Acari, Oribatida) in gardens. Acta fytotechn. Zootechn. 2020, 23, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madge, D.S. The humidity reactions of oribatid mites. Acarologia 1964, 6, 566–591. [Google Scholar]

- Seniczak, A.; Seniczak, S.; Słowikowska, M.; Paluszak, Z. The effect of different diet on life history parameters and growth of Oppia denticulata (Acari: Oribatida: Oppiidae). Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2017, 22, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepel, H. Life-history tactics of soil microarthropods. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1994, 18, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, P.; Straalen, N.M. Oribatid mites: Prospects for their use in ecotoxicology. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1995, 19, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miko, L. Oribatid mites may actively migrate faster and over longer distances than anticipated: Experimental evidence for Damaeus onustus (Acari: Oribatida). Soil Organ. 2016, 88, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Smrž, J. Survival of Scutovertex minutus (Koch) (Acari: Oribatida) under differing humidity conditions. Pedobiologia 1994, 38, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianciolo, J.M.; Norton, R.A. The ecological distribution of reproductive mode in oribatid mites, as related to biological complexity. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2006, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, I.; Domes, K.; Heethoff, M.; Schneider, K.; Schön, I.; Norton, R.A.; Scheu, S.; Maraun, M. No evidence for the ‘Meselson effect’ in parthenogenetic oribatid mites (Oribatida, Acari). J. Evol. Biol. 2006, 19, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, R.A.; Palmer, S.C. The distribution, mechanisms and evolutionary significance of parthenogenesis in oribatid mites. In The Acari: Reproduction, Development and Life-History Strategies; Schuster, R., Murphy, P.W., Eds.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1991; pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.A.; Kethley, J.B.; Johnston, D.E.; OConnor, B.M. Phylogenetic perspectives on genetic systems and reproductive modes of mites. In Evolution and Diversity of Sex Ratio in Insects and Mites; Wrensch, D., Ebbert, M., Eds.; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 8–99. [Google Scholar]

- Heethoff, M.; Domes, K.; Laumann, M.; Maraun, M.; Norton, R.A.; Scheu, S. High genetic divergences indicate ancient separation of parthenogenetic lineages of the oribatid mite Platynothrus peltifer (Acari, Oribatida). J. Evol. Biol. 2007, 20, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrensch, D.L.; Kethley, J.B.; Norton, R.A. Cytogenetics of holokinetic chromosomes and inverted meiosis: Keys to the evolutionary success of mites, with generalizations on eukaryotes. In Ecological and Evolutionary Analyses of Life-History Patterns; Houck, M.A., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 282–343. [Google Scholar]

- Søvik, G.; Leinaas, H.P. Long life cycle and high adult survival in an arctic population of the mite Ameronothrus lineatus (Acari, Oribatida) from Svalbard. Polar. Biol. 2003, 26, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domes-Wehner, K. Parthenogenesis and Sexuality in Oribatid Mites: Phylogeny, Mitochondrial Genome Structure and Resource Dependence. Doctoral Dissertation, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heethoff, M.; Norton, R.A.; Scheu, S.; Maraun, M. Parthenogenesis in Oribatid Mites (Acari, Oribatida): Evolution Without Sex. In Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis; Schön, I., Martens, K., Dijk, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberly, G. Recherches sur la parthénogenèse thélythoque de deux espèces d’acariens oribatides: Trhypochthonius tectorum (Berlese) et Platynothrus peltifer (Koch). IV Observations sur les mâles ataviques. Acarologia 1988, 29, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

| Morphological Characters | Larva | Protonymph | Deutonymph | Tritonymph | Adult |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body length | 255 ± 3.99 | 331 ± 4.95 | 417 ± 17.82 | 546 ± 26.44 | 632 ± 27.50 |

| Body width | 162 ± 4.16 | 197 ± 5.49 | 251 ± 7.78 | 340 ± 5.87 | 362 ± 7.08 |

| Prodorsum length | 80 ± 3.68 | 105 ± 3.07 | 118 ± 2.64 | 180 ± 3.33 | 227 ± 13.35 |

| Length of seta ro | 27 ± 1.32 | 34 ± 1.35 | 43 ± 1.26 | 49 ± 2.17 | 58 ± 4.19 |

| seta le | 29 ± 2.30 | 35 ± 1.78 | 44 ± 1.64 | 50 ± 1.90 | 65 ± 7.54 |

| seta in | 5 ± 0.32 | 8 ± 0.53 | 13 ± 0.82 | 14 ± 0.88 | 48 ± 2.90 |

| seta ex | 26 ± 1.27 | 32 ± 2.86 | 34 ± 2.12 | 47 ± 3.92 | 55 ± 6.48 |

| seta bs | 125 ± 6.79 | 139 ± 10.31 | 165 ± 7.17 | 186 ± 14.98 | 164 ± 17.54 |

| seta c1 | 56 ± 3.43 | 70 ± 2.81 | 80 ± 3.98 | 110 ± 15.17 | 39 ± 3.78 |

| seta c2 | 43 ± 2.31 | 36 ± 2.12 | 43.2 ± 2.74 | 60 ± 11.20 | 56 ± 4.49 |

| seta c3 | 107 ± 4.48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | lost |

| seta da | 84 ± 4.40 | lost | lost | lost | lost |

| seta dp | 180 ± 8.38 | lost | lost | lost | lost |

| seta la | 130 ± 4.90 | 33 ± 1.93 | 43 ± 2.00 | 49 ± 5.95 | 113 ± 10.88 |

| seta lp | 77 ± 3.45 | 22 ± 1.20 | 23 ± 1.78 | 33 ± 5.06 | 128 ± 7.99 |

| seta h1 | 149 ± 7.25 | 182 ± 7.77 | 242 ± 20.34 | 280 ± 21.96 | 115 ± 14.24 |

| seta h2 | 25 ± 3.07 | 40 ± 2.32 | 44 ± 2.21 | 73 ± 8.47 | 130 ± 7.70 |

| seta h3 | 12 ± 1.90 | 168 ± 11.29 | 215 ± 18.78 | 265 ± 18.98 | 121 ± 11.72 |

| seta p1 | nd | 23 ± 1.40 | 37 ± 1.14 | 57 ± 9.81 | 93 ± 17.68 |

| seta p2 | nd | 22 ± 1.51 | 32 ± 1.37 | 36 ± 3.22 | 118 ± 13.56 |

| seta p3 | nd | 20 ± 0.99 | 27 ± 1.43 | 30 ± 4.19 | 122 ± 15.58 |

| genital opening | nd | 29 ± 2.44 | 51 ± 4.00 | 74 ± 9.57 | 83 ± 6.34 |

| anal opening | 58 ± 2.00 | 75 ± 1.89 | 80 ± 2.26 | 113 ± 11.12 | 117 ± 8.59 |

| Morphological Characters | Larva | Protonymph | Deutonymph | Tritonymph | Adult |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape of seta ro | smooth | smooth | smooth | barbed unilaterally | barbed unilaterally |

| seta le | smooth | smooth | smooth | barbed unilaterally | barbed unilaterally |

| seta in | smooth | smooth | smooth | smooth | barbed bilaterally |

| seta ex | smooth | smooth | smooth | smooth | smooth |

| seta bs | barbed bilaterally | barbed bilaterally | barbed bilaterally | barbed bilaterally | barbed unilaterally |

| Notogastral/Gastronotal setae (pairs) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| Notogastral/Gastronotal seta c3 | present | vestigial | vestigial | vestigial | lost |

| Formula of epimeral setae | 3–1–2 | 3–1–3–1 | 3–1–3–2 | 3–1–3–3 | 3–1–3–3 |

| Genital (valves) setae (pairs) | nd | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Aggenital (valves) setae (pairs) | nd | nd | 2 | 5 | neotrichous (17–19 pairs total) |

| Anal (valves) setae (pairs) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Adanal (valves) setae (pairs) | nd | nd | 3 | 5 | neotrichous (17–19 pairs total) |

| Morphological Characters | E. eharai | E. geographica | E. gracilior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | |||

| Rostrum shape | rounded | rounded | triangular |

| Notogastral setae shape | very curved 1, smooth | slightly curved, smooth | slightly curved, barbed |

| Notogastral seta c1 length | shorter than c2 | as long as c2 | as long as c2 |

| Subcapitular seta h shape | stellate branches | ciliate branches | ciliate branches |

| amr | present | absent | absent |

| Epimeral setae 1b, 3b, 3c, 4a shape | stellate branches | setiform | ciliate branches |

| Epimeral setae 4b | setiform | setiform | phylliform |

| 3c and 4c inserted on tubercles | yes | no | yes |

| Stellate neotrichous setae | yes | no | no |

| Tritonymph | |||

| Gastronotal seta c3 length | 0 | 145 | |

| Number of genital valve setae (pairs) | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Number of adanal valve setae (pairs) | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Deutonymph | |||

| Gastronotal seta c3 length | 0 | 115 | |

| Number of genital valve setae (pairs) | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Protonymph | |||

| Gastronotal seta c3 length | 0 | 109 | |

| Number of anal valve setae (pairs) | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Larva | |||

| Seta bs | barbed bilaterally | barbed unilaterally | smooth |

| Gastronotal seta c1 | smooth | barbed unilaterally | barbed |

| Number of anal valve setae (pairs) | 1 | 2 |

| Developmental Stages | Number of Specimens | Mean (±SE) | 95% CIs (Lower–Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg Duration | 91 | 6.47 ± 0.05 | 6.37–6.58 |

| Larva Duration | 91 | 12.15 ± 0.14 | 11.89–12.42 |

| Protonymph Duration | 91 | 8.66 ± 0.09 | 8.48–8.84 |

| Deutonymph Duration | 91 | 9.05 ± 0.08 | 8.89–9.22 |

| Tritonymph Duration | 91 | 11.65 ± 0.14 | 11.37–11.92 |

| Larva Quiescent Duration | 91 | 17.89 ± 0.17 | 17.56–18.22 |

| Protonymph Quiescent Duration | 91 | 14.29 ± 0.12 | 14.05–14.52 |

| Deutonymph Quiescent Duration | 91 | 15.69 ± 0.10 | 15.50–15.89 |

| Tritonymph Quiescent Duration | 91 | 5.01 ± 0.10 | 4.81–5.21 |

| Total Immature Duration | 91 | 47.99 ± 0.19 | 47.62–48.36 |

| Adult–Egg | 91 | 22.58 ± 0.16 | 22.27–22.89 |

| Egg–Egg | 91 | 70.57 ± 0.16 | 70.27–70.88 |

| Species | Food Sources | Temperature (℃) | Humidity (%) | Total Immature Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. eharai | active dry yeast | 25 ± 3 | 80 ± 5 | 47.99 |

| E. geographica | Aspergillus flavus | 25 | 100 | 56–74 |

| E. gracilior | Trichoderma koningii | 20 | 70–80 | 68–75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chu, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. Morphological Ontogeny and Life Cycle of Laboratory-Maintained Eremobelba eharai (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae). Insects 2026, 17, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010047

Chu C, Chen Y, Chen J. Morphological Ontogeny and Life Cycle of Laboratory-Maintained Eremobelba eharai (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae). Insects. 2026; 17(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Chang, Yu Chen, and Jun Chen. 2026. "Morphological Ontogeny and Life Cycle of Laboratory-Maintained Eremobelba eharai (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae)" Insects 17, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010047

APA StyleChu, C., Chen, Y., & Chen, J. (2026). Morphological Ontogeny and Life Cycle of Laboratory-Maintained Eremobelba eharai (Acari: Oribatida: Eremobelbidae). Insects, 17(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010047