New Insights into the Phenology and Overwintering Biology of Glyptapanteles porthetriae, a Parasitoid of Lymantria dispar

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.1.1. Evaluation of Host Population Density

2.1.2. Sampling Techniques and Recording of Phenological Data

2.1.3. Parasitization of L. dispar by G. porthetriae

2.1.4. Hyper-parasitization of G. porthetriae

2.2. Laboratory Experiments on the Overwintering Biology of G. porthetriae

2.2.1. Experiment 1—Overwintering of G. porthetriae in Field-Collected L. dispar Eggs

2.2.2. Experiment 2—Overwintering of G. porthetriae in Laboratory-Exposed L. dispar Eggs

2.2.3. Experiment 3—Dormancy Induction in Endoparasitic Larvae or Cocooned Prepupae

2.2.4. Experiment 4—Impact of Autumn Conditions on G. porthetriae Development in L. dispar Hosts Under Semi-Field Conditions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Field Study—Host Population Density and Phenology of L. dispar

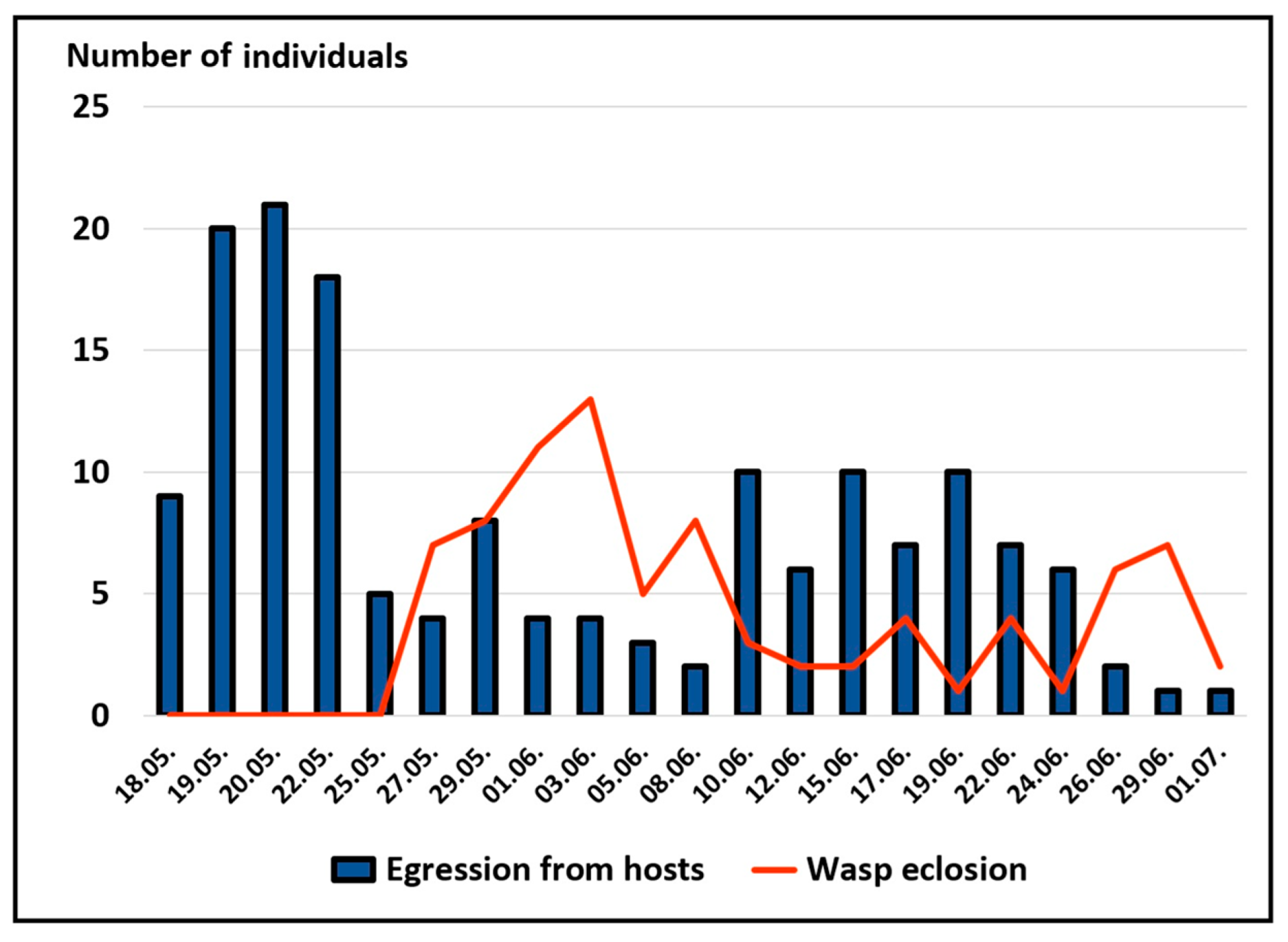

3.1.1. Field Study—Emergence Rates of G. porthetriae from L. dispar Larvae

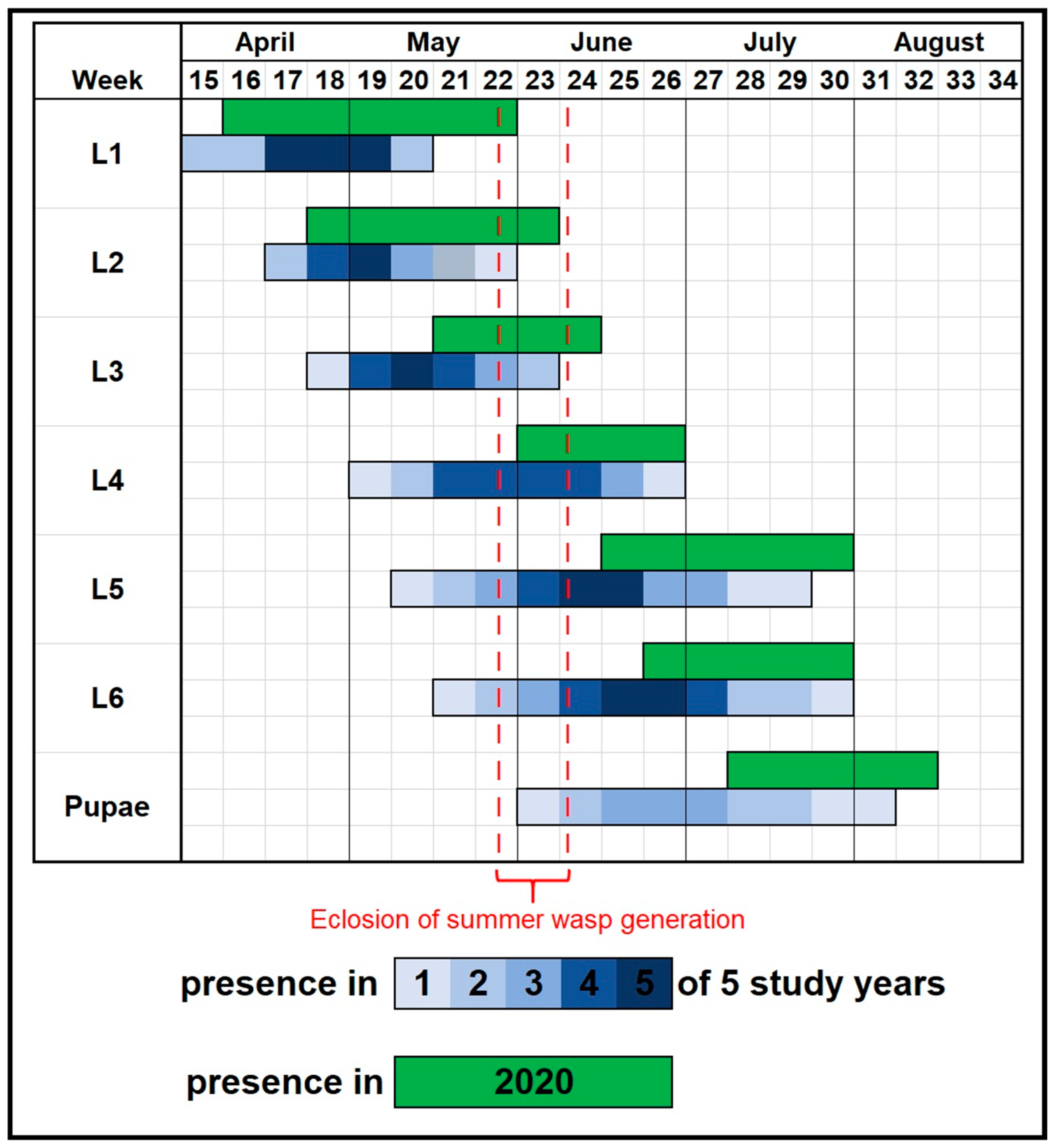

3.1.2. Field Study—Phenology and Eclosion of G. porthetriae

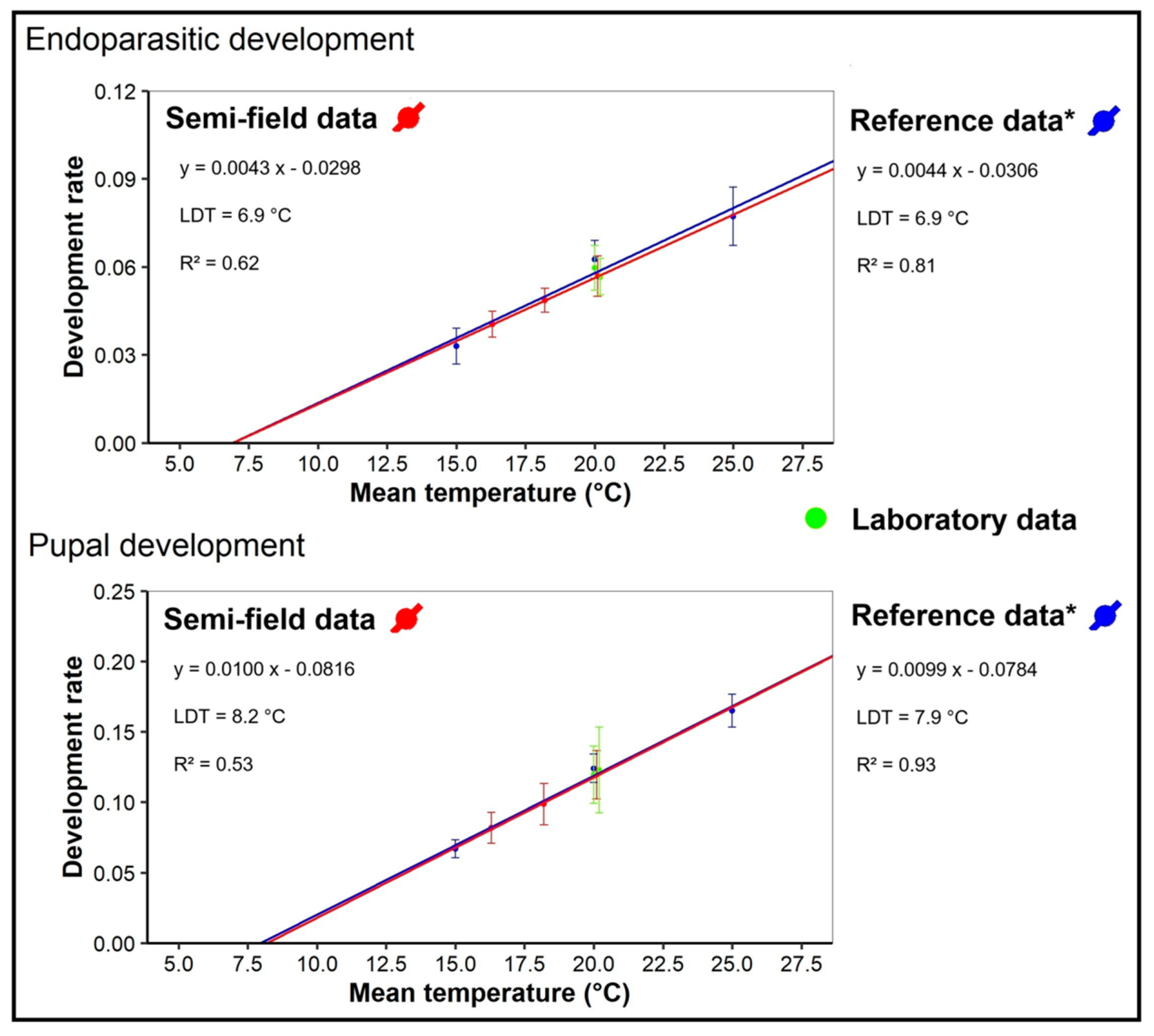

3.2. Development of G. porthetriae as Egg–Larval Parasitoid

3.3. Dormancy Induction in Endoparasitic Larvae or Cocooned Prepupae

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APHIS | Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service |

| L2d3 | three days post moult to the second instar |

| LDT | Lower Developmental Threshold |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

References

- Boukouvala, M.C.; Kavallieratos, N.G.; Skourti, A.; Pons, X.; López Alonso, C.; Eizaguirre, M.; Benavent Fernandez, E.; Domínguez Solera, E.; Fita, S.; Bohinc, T.; et al. Lymantria dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae): Current Status of Biology, Ecology, and Management in Europe with Notes from North America. Insects 2022, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindos, M.; Liebhold, A.M. The spongy moth, Lymantria dispar. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zúbrik, M.; Kunca, A.; Kulfan, J.; Rell, S.; Nikolov, C.; Galko, J.; Vakula, J.; Gubka, A.; Leontovyč, R.; Konôpka, B.; et al. Occurrence of gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar L.) in the Slovak Republic and its outbreak during 1945–2020. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2021, 67, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, B.M.; Seibold, S.; Morinière, J.; Bozicevic, V.; Jaworek, J.; Roth, N.; Vogel, S.; Zytynska, S.; Petercord, R.; Eichel, P.; et al. Metabarcoding of canopy arthropods reveals negative impacts of forestry insecticides on community structure across multiple taxa. J. Appl. Entomol. 2021, 59, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalouni, U.; Schädler, M.; Brandl, R. Natural enemies and environmental factors affecting the population dynamics of the gypsy moth. J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 137, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopf, A.; Hoch, G. Zur Bionomie und Bedeutung von Glyptapanteles liparidis (Hym., Braconidae) als Regulator von Lymantria dispar (Lep., Lymantriidae) in Gebieten mit unterschiedlichen Populationsdichten. J. Appl. Entomol. 1997, 121, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankl, T.; Schafellner, C.; Hoch, G. Parasitoids and pathogens in a collapsing Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) population in Lower Austria. J. Appl. Entomol. 2023, 147, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougeron, K. Diapause research in insects: Historical review and recent work perspectives. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2019, 167, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.R.; Skelton, M.J. Parasitism (Hymenoptera: Braconidae, Microgastrinae) in an apparently adventitious colony of Lymantria dispar (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) in southern England, with speculations on the biology of Glyptapanteles porthetriae (Muesebeck). Ent. Gaz. 2008, 59, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, A.F.; Crossman, S.S. Imported Insect Enemies of the Gypsy Moth and the Brown-Tail Moth; Technical Bulletin No. 86; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1929; pp. 1–147. [CrossRef]

- Žikić, V.; Lazarević, M.; Stanković, S.S.; Milošević, M.I. New data on Microgastrinae in Serbia and Montenegro (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and their hosts. Biol. Nyssana 2015, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, K.J. The Parasites and Predators of the Gypsy Moth: A Review of the World Literature with Special Application to Canada; Canadian Forestry Service: Saulte Ste. Marie, ON, Canada, 1976; pp. 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Marktl, R.C.; Stauffer, C.; Schopf, A. Interspecific competition between the braconid endoparasitoids Glyptapanteles porthetriae and Glyptapanteles liparidis in Lymantria dispar larvae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2002, 105, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer, C.; Schopf, A. Development of the solitary larval endoparasitoid Glyptapanteles porthetriae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in its host Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2000, 97, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čapek, M. The Braconidae (Hymenoptera) as parasitoids of the gypsy moth Lymantria dispar L. (Lepidoptera). Acta Inst. For. Zvolen. 1988, 7, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, G.; Zúbrik, M.; Novotný, J.; Schopf, A. The natural enemy complex of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar (Lep., Lymantriidae) in different phases of its population dynamics in eastern Austria and Slovakia—A comparative analysis. J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Györfi, J. Die Schlupfwespen und der Unterwuchs des Waldes. Z. Angew. Entomol. 1952, 33, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, K. Potential Alternate Hosts of the Gypsy Moth Parasite Apanteles porthetriae. Environ. Entomol. 1977, 9, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.R.; Huddlestone, T. Classification and Biology of Braconid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). In Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects; Royal Entomological Society: St Albans, UK, 1991; Volume 7, pp. 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Johannson, A.S. Studies on the relation between Apanteles glomeratus L. (Hym., Braconidae) and Pieris brassicae L. (Lepid., Pieridae). Nor. Entomol. Tidsskr. 1951, 8, 145–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert, H. Apanteles pierids (Bouché) (Hym., Braconidae), ein Parasit von Aporia crataegi (L.) (Lep., Pieridae). Entomophaga 1960, 3, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Penna, D.C.; Whitfield, J.B.; Janzen, D.H.; Hallwachs, W.; Dyer, L.A.; Smith, M.A.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Fernández-Triana, J.L. A species-level taxonomic review and host associations of Glyptapanteles (Hymenoptera, Braconidae, Microgastrinae) with an emphasis on 136 new reared species from Costa Rica and Ecuador. ZooKeys 2019, 890, 1–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koštál, V. Eco-physiological phases of insect diapause. J. Insect Phys. 2006, 52, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koštál, V.; Havelka, J.; Šimek, P. Low-temperature storage and cold hardiness in two populations of the predatory midge Aphidoletes aphidimyza, differing in diapause intensity. Physiol. Entomol. 2001, 26, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgolastra, F.; Bosch, J.; Molowny-Horas, R.; Maini, S.; Kemp, W.P. Effect of temperature regime on diapause intensity in an adult-wintering Hymenopteran with obligate diapause. J. Insect Phys. 2010, 56, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.R.; Ravlin, F.W.; Régnière, J.; Logan, J.A. Further Advances Toward a Model of Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar (L.)) Egg Phenology: Respiration Rates and Thermal Responsiveness During Diapause, and Age-dependent Developmental Rates in Postdiapause. J. Insect Phys. 1995, 41, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Tang, L.-D.; Desneux, N.; Zang, L.-S. Diapause in parasitoids: A systematic review. J. Pest Sci. 2025, 98, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzembowska, A. Temperature-Related Development and Adult Wasp Longevity of Three Endoparasitic Glyptapanteles Species (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in Their Host Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Master Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turček, F.J. Mníška Veľkohlavá [The Gypsy Moth]; SVPL: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1956; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenke, W. Die Forstschädlinge Europas—Ein Handbuch in Fünf Bänden. Band 3—Schmetterlinge; Verlag Paul Parey: Hamburg, Germany; Berlin, Germany, 1978; pp. 1–467. [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev, V.I.; Andreeva, E.M.; Shatalin, N.V. Group Effect in the Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar, Lepidoptera, Lymantriidae) Related to the Population Characteristics and Food Composition. Entomol. Rev. 2009, 89, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, E.E.; Reardon, R.C.; Ticehurst, M. Selected Parasites and Hyperparasites of the Gypsy Moth, with Keys to Adults and Immatures; Agriculture Handbook No. 540; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; pp. 1–59.

- Broad, G. Identification Key to the Subfamilies of Ichneumonidae (Hymenoptera); The Natural History Museum: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R.A.; Owens, C.D.; Shapiro, M.; Tardif, J.R. Development of mass rearing technology. In The Gypsy Moth: Research Toward Integrated Pest Management; Technical Bulletin 1584; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1981; pp. 599–633. [Google Scholar]

- Pruscha, H. A volumetric micro-respirometer with automatic recording equipment. Oecologia 1984, 62, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, G. Der Antagonistenkomplex des Schwammspinners, Lymantria dispar L. (Lep.: Lymantriidae) in Populationen Hoher, Mittlerer und Niederer Dichte im Burgenland. Diploma Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbacher, G. Untersuchungen zum Parasitoidenkomplex des Schwammspinners, Lymantria dispar (Lep., Lymantriidae), in seiner Progradations-und Kulminationsphase. Diploma Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fuester, R.W.; Drea, J.J.; Gruber, F.; Hoyer, H.; Mercadier, G. Larval parasites and other natural enemies of Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) in Burgenland, Austria, and Würzburg, Germany. Environ. Entomol. 1983, 12, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, O. Experimental studies upon the parasitoid complex of the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar L.) (Lep. Lymantriidae) in lower host populations in eastern Austria. J. Appl. Entomol. 1996, 120, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcáni, M.; Novotný, J.; Zúbrik, M.; McManus, M.; Pilarska, D.; Maddox, J. The role of biotic factors in gypsy moth population dynamics in Slovakia: Present knowledge. In Integrated Management and Dynamics of Forest Defoliating Insects; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 152–167. [Google Scholar]

- Drea, J.J.; Fuester, R.W. Larval and pupal parasitoids of Lymantria dispar and notes on parasites of other Lymantriidae [Lep.] in Poland 1975. Entomophaga 1979, 24, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, K. Beitrag zur Biologie primärer und sekundärer Parasitoide von Lymantria dispar L. (Lep., Lymantriidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 1990, 110, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukovata, L.; Fuester, R.W. Effects of gypsy moth population density and host-tree species on parasitism. In Proceedings of the 16th U.S. Department of Agriculture Interagency Research Forum on Gypsy Moth and Other Invasive Species, Amherst, MA, USA, 18–21 January 2005; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Zolubas, P.; Gedminas, A.; Shields, K. Gypsy moth parasitoids in the declining outbreak in Lithuania. J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimović, M.; Sivčec, I. Further studies on the numerical increase of natural enemies of the Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar L.) in forests. Z. Angew. Entomol. 1984, 98, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuester, R.W.; Ramaseshiah, G. A comparison of the parasite complexes attacking two closely related Lymantriids. In Lymantriidae: A Comparison of Features of New and Old World Tussock Moths; General Technical Report NE-125; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; pp. 501–516. [Google Scholar]

- Stattler, S.; Grünfelder, M.; Schafellner, C. Vergleich von thermalen Kennwerten von Freiland-und Labortieren des Schwammspinners, Lymantria dispar—Comparison of thermal traits of field collected and laboratory strains of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar. In ALVA-Tagungsbericht 2021; Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Lebensmittel, Veterinär-und Agrarwesen: Vienna, Austria, 2021; pp. 365–367. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer, C.; Stradner, A.; Schopf, A. Effects of parasitization or injection of parasitoid-derived factors from the endoparasitic wasp Glyptapanteles porthetriae (Hym., Braconidae) on the development of the larval host, Lymantria dispar (Lep., Lymantriidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2002, 126, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Fang, G.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Z.; Chen, J.; Feng, T.; Zhang, Q.; Sheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Coordinated molecular and ecological adaptations underlie a highly successful parasitoid. eLife 2024, 13, RP94748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramitsu, K.; Kainoh, Y.; Konno, K. Multiparasitism enables a specialist endoparasitoid to complete parasitism in an unsuitable host caterpillar. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Matsutani, H.; Okumura, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Sawa, T.; Nakamatsu, Y. Insufficient Polydnavirus Injection as a Physiological Factor Preventing Successful Parasitization by Cotesia ruficrus on Final Instar Host Larvae. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 119, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfmann, E. Complementary Sex Determination in the Gregarious Endoparasitic Wasp Glyptapanteles liparidis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Master’s Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weseloh, R.M. Population sampling method for cocoons of the gypsy moth (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) parasite, Apanteles melanoscelus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), and relationship of its population levels to predator-and hyperparasite-induced mortality. Environ. Entomol. 1983, 12, 1228–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, E.H.; Bruinsma, M.; Zhu, F.; Weldegergis, B.T.; Boursault, A.E.; Jongema, Y.; van Loon, J.J.A.; Vet, L.E.M.; Harvey, J.A.; Dicke, M. Hyperparasitoids Use Herbivore-Induced Plant Volatiles to Locate Their Parasitoid Host. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D.K.; Paul, R.L.; Gates, M.W.; Kubik, T.; Harvey, J.A.; Kondratieff, B.C.; Ode, P.J. Shared enemies exert differential mortality on two competing parasitic wasps. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2020, 47, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberson, J.R.; Whitfield, J.B. Facultative egg-larval parasitism of the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) by Cotesia marginiventris (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Fla. Entomol. 1996, 79, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljesthröm, G.G.; Cingolani, M.F.; Roggiero, M.F. Susceptibility of Nezara viridula (L.) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) Egg Masses of Different Sizes to Parasitism by Trissolcus basalis (Woll.) (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) in the Field. Neotrop. Entomol. 2014, 43, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.R. Notes on some European Microgastrinae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in the National Museums of Scotland, with twenty species new to Britain, new host data, taxonomic changes and remarks, and descriptions of two new species of Microgaster Latreille. Entomol. Gaz. 2021, 63, 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, U.A.M.; Shi, Z.-H.; Guo, Y.-L.; Zou, X.-F.; Hao, Z.-P.; Pang, S.-T. Maternal photoperiod effect on and geographic variation of diapause incidence in Cotesia plutellae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) from China. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2007, 42, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D.S. Insect photoperiodism: Effects of temperature on the induction of insect diapause and diverse roles for the circadian system in the photoperiodic response. Entomol. Sci. 2014, 17, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, M.A. Hybridization of Strains of the Gypsy Moth Parasitoid, Apanteles melanoscelus, and its Influence upon Diapause. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1975, 68, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, S.M.; Momoi, S. Environmental Regulation and Geographical Adaptation of Diapause in Cotesia plutellae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a Parasitoid of the Diamondback Moth Larvae. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1994, 29, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leather, S.R.; Walters, K.F.A.; Bale, J.S. The Ecology of Insect Overwintering; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 1–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert, H. Apanteles glomeratus (L.) als Parasit von Aporia crataegi (L.) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Beitr. Entomol. 1959, 9, 874–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevskii, A.S. Photoperiodism and Seasonal Development of Insects; Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh, UK; London, UK, 1965; pp. 1–283. [Google Scholar]

- Weseloh, R.M. Termination and induction of diapause in the gypsy moth larval parasitoid, Apanteles melanoscelus. J. Insect Physiol. 1973, 19, 2025–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.L.; Leonard, D.E. Mortality factors of Satin Moth, Leucoma salicis [Lep.: Lymantriidae], in Aspen Forests in Maine. Entomophaga 1980, 25, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschnig, M. Development of the Braconid Wasp Glyptapanteles liparidis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in Larvae of the Brown-Tail Moth, Euproctis chrysorrhoea (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Lymantriinae). Master’s Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, F. Untersuchungen zur Eignung von Raupen des Goldafters Euproctis chrysorrhoea (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) als Überwinterungswirt für die Brackwespe Glyptapanteles liparidis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Master’s Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schopf, A. Studien zur Entwicklungsbiologie und Ökologie von endoparasitischen Braconiden unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung des Wirt-Parasit-Systems Lymantria dispar (Lep., Lymantriidae)—Glyptapanteles liparidis (Hym., Braconidae). Habilitation Thesis, BOKU University, Vienna, Austria, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cadahia, D.; Demolin, G.; Biliotti, E. Meteorus versicolor Wesm. var. decoloratus Ruthe [Hym. Braconidae] Parasite Noveau de Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff. [Lep. Thaumetopoeidae]. Entomophaga 1967, 12, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muesebeck, C.F. Two important introduced parasites of the browntail moth. J. Agric. Res. 1918, 14, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zankl, T.; Schafellner, C. Eignung potenzieller Überwinterungswirte für parasitische Gegenspieler des Schwammspinners (Lymantria dispar) (Lep.: Erebidae). Entomol. Austriaca 2025, 32, 217–219. [Google Scholar]

- Held, C.; Spieth, H.R. First evidence of pupal summer diapause in Pieris brassicae L.: The evolution of local adaptedness. J. Insect Physiol. 1999, 45, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Instar | 14 May | 26 May | 2 June | 16 June | 23 June | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 10.1 (10) a | - | - | - | - | 10.1 (10) a |

| L2 | 35.7 (85) b | - | - | - | - | 35.7 (85) b |

| L3 | - | A 18.0 (9) | A 30.9 (27) a | B 81.8 (9) a | - | 30.2 (45) b |

| L4 | - | - | A 8.9 (4) b | B 40.0 (14) b | AB 25.0 (1) | 22.6 (19) ab |

| L1–L4 | A 28.2 (95) | A 18.0 (9) | A 23.3 (31) | B 50.0 (23) | AB 25.0 (1) | 28.1 (160) |

| Early Instars (L1 + L2) | Mid Instars (L3 + L4) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasitoid emergence rate (%) | 28 | 27 | 0.924 |

| Wasp eclosion rate (%) | 63 | 39 | 0.004 |

| Sex ratio (F:M) | 50:50 | 23:77 | 0.042 |

| G. porthetriae | Hyperparasitoids | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wasp eclosion rate (%) | 13 | 44 | 58 |

| Days from collection to eclosion | 6.3 ± 6.0 | 28.5 ± 5.1 |

| Laboratory Trial | 16L:8D | 12L:12D | p-Value | |

| Emergence rate (%) | 72 | 56 | 0.377 | |

| Eclosion rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | |

| Premature host death (%) | 0 | 8 | 0.490 | |

| Host pupation (%) | 28 | 36 | 0.762 | |

| Endoparasitic dev. (days) | 17.1 ± 2.3 | 17.6 ± 1.9 | 0.296 | |

| Pupal development (days) | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 8.3 ± 2.1 | 0.772 | |

| Respiration (µL O2 mg−1 h−1) | 0.81 ± 0.42 | 0.83 ± 0.35 | 0.881 | |

| Semi-Field Trial | Early Sep | Mid Sep | Late Sep | p-Value |

| Emergence rate (%) | 65 | 55 | 70 | 0.709 |

| Eclosion rate (%) | 92 | 100 | 91 | 0.522 |

| Premature host death (%) | 20 | 15 | 10 | 0.900 |

| Host pupation (%) | 15 | 30 | 20 | 0.630 |

| Endoparasitic dev. (days) | 17.8 ± 2.2 a | 20.7 ± 1.8 b | 25.0 ± 2.9 c | < 0.001 |

| Pupal development (days) | 8.5 ± 1.3 a | 10.4 ± 1.6 b | 12.5 ± 1.8 c | < 0.001 |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 20.1 ± 4.2 a | 18.2 ± 3.4 b | 16.3 ± 3.7 c | < 0.001 |

| Photoperiod (hours) | 13.5–12.5 | 12.5–11.0 | 12.0–10.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zankl, T.; Schafellner, C. New Insights into the Phenology and Overwintering Biology of Glyptapanteles porthetriae, a Parasitoid of Lymantria dispar. Insects 2025, 16, 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121270

Zankl T, Schafellner C. New Insights into the Phenology and Overwintering Biology of Glyptapanteles porthetriae, a Parasitoid of Lymantria dispar. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121270

Chicago/Turabian StyleZankl, Thomas, and Christa Schafellner. 2025. "New Insights into the Phenology and Overwintering Biology of Glyptapanteles porthetriae, a Parasitoid of Lymantria dispar" Insects 16, no. 12: 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121270

APA StyleZankl, T., & Schafellner, C. (2025). New Insights into the Phenology and Overwintering Biology of Glyptapanteles porthetriae, a Parasitoid of Lymantria dispar. Insects, 16(12), 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121270