Odorant Binding Proteins in Tribolium castaneum: Functional Diversity and Emerging Applications

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Tribolium castaneum: A Global Pest and Powerful Genetic Model

1.2. Odorant Binding Proteins: Canonical Roles in Insect Chemoreception

2. Molecular Architecture and Functional Dynamics of T. castaneum OBPs

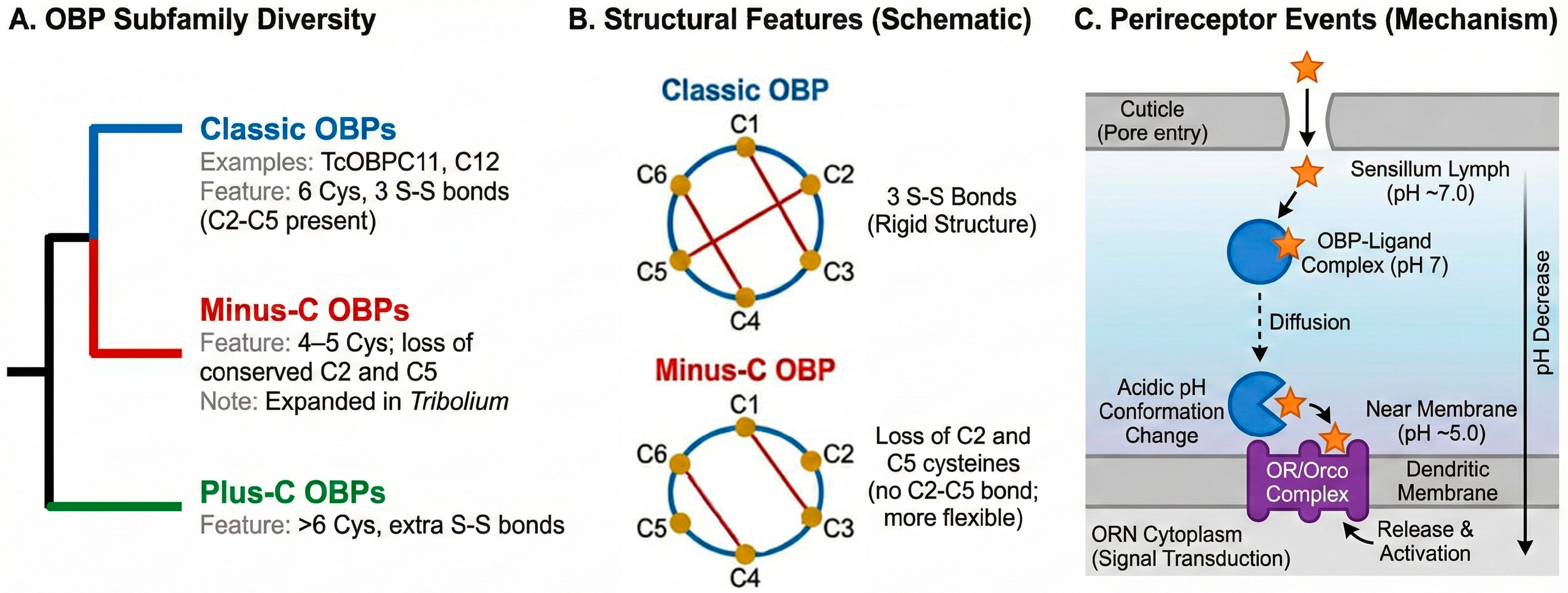

2.1. Structural Hallmarks and Subfamily Diversity

2.2. Ligand Binding: Specificity, Affinity, and Release Mechanisms

2.3. The OBP-Receptor Interface and Signal Transduction

3. Genomic Organization, Expression, and Regulation

3.1. A Spatiotemporal Expression Atlas of T. castaneum OBPs

3.2. The Regulatory Network: Transcriptional, Hormonal, and Environmental Control

3.3. Emerging Layers of Regulation: Epigenetic Modifications and miRNA Regulations

4. The Expanding Functional Repertoire of T. castaneum OBPs

4.1. Central Roles in Detoxification and Defense Against Xenobiotics

4.2. Contributions to Innate Immunity and Other Physiological Processes

5. Translational Prospects: Leveraging OBP Biology for Innovation

5.1. Targeting OBPs for Novel Pest Management Strategies

5.1.1. OBP-Modulating Compounds as Repellents and Insecticides

5.1.2. RNA Interference (RNAi) as a Tool for OBP-Targeted Control

5.2. OBPs in Biotechnology: From Biosensors to Bioremediation

5.2.1. OBP-Based Biosensors

5.2.2. Other Potential Applications

6. Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives

6.1. Evolution of the OBP Gene Family in Coleoptera

6.2. Functional Divergence and Conservation Across Insecta

7. Synthesis and Future Outlook

7.1. Summary of Key Advances and Emerging Paradigms

7.2. Current Gaps, Challenges, and Future Research Frontiers

- CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing: Moving beyond the transient effects of RNAi, CRISPR/Cas9 technology allows for the creation of stable, heritable knockout lines for precise functional analysis. Crucially, it enables the generation of multi-gene knockouts, which will be essential for overcoming the challenge of functional redundancy and dissecting the roles of clustered or closely related OBP genes.

- Single-Cell Transcriptomics (scRNA-seq): This revolutionary technology provides the ability to resolve OBP expression profiles at the ultimate level of resolution: single cells. Applying scRNA-seq to the beetle’s antennae and other tissues will create a high-resolution atlas of the chemosensory and defensive systems, identifying the precise cellular context in which each OBP functions and revealing novel, rare cell types that may have been missed by bulk analyses.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: The growing volume of sequence, structure, and functional data for OBPs is ripe for the application of AI. Machine learning models can be trained to predict ligand-binding properties with increasing accuracy, to perform virtual screening of immense chemical libraries for novel OBP inhibitors or modulators, and to mine large-scale ‘omics datasets to generate new, data-driven hypotheses about OBP function.

- Structural Biology: A concerted effort to solve the experimental 3D structures of key TcOBPs—both in their unbound (apo) form and in complex with ecologically relevant ligands—is a critical priority. Techniques like X-ray crystallography, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) will provide the atomic-level detail necessary to understand the dynamics of ligand binding and release, which is the essential foundation for the rational design of next-generation pest control molecules.

- Systems Biology: Ultimately, the goal is to move beyond studying individual proteins in isolation. The future lies in integrating these multilevel data streams—genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, structural, and functional—to build systems-level models of the beetle’s entire chemosensory and defensive apparatus. This will allow researchers to understand how the system as a whole responds to complex chemical environments and to predict the consequences of targeted interventions. From an applied standpoint, it is also important to recognize practical constraints. Field deployment of OBP-targeted RNAi will have to contend with dsRNA instability, formulation costs, and regulatory hurdles, while OBP-based biosensors must be engineered into robust, user-friendly devices before they can move beyond laboratory prototypes. Likewise, turning high-affinity OBP ligands into viable repellents, attractants, or synergists involves extensive medicinal chemistry and safety evaluation. Explicitly acknowledging these constraints provides a more realistic context for the promising translational opportunities outlined above.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, A.; Agashe, D. The Red Flour Beetle Tribolium castaneum: A Model for Host-Microbiome Interactions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.F.; Athanassiou, C.G.; Hagstrum, D.W.; Zhu, K.Y. Tribolium castaneum: A Model Insect for Fundamental and Applied Research. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2022, 67, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingler, M.; Bucher, G. The Red Flour Beetle T. castaneum: Elaborate Genetic Toolkit and Unbiased Large Scale RNAi Screening to Study Insect Biology and Evolution. EvoDevo 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösner, J.; Wellmeyer, B.; Merzendorfer, H. Tribolium castaneum: A Model for Investigating the Mode of Action of Insecticides and Mechanisms of Resistance. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 3554–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herndon, N.; Shelton, J.; Gerischer, L.; Ioannidis, P.; Ninova, M.; Dönitz, J.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Liang, C.; Damm, C.; Siemanowski, J. Enhanced Genome Assembly and a New Official Gene Set for Tribolium castaneum. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt-Engel, C.; Schultheis, D.; Schwirz, J.; Ströhlein, N.; Troelenberg, N.; Majumdar, U.; Dao, V.A.; Grossmann, D.; Richter, T.; Tech, M. The iBeetle Large-Scale RNAi Screen Reveals Gene Functions for Insect Development and Physiology. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihani, K.; Ferveur, J.-F.; Briand, L. The 40-Year Mystery of Insect Odorant-Binding Proteins. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.S.; Xiao, S.; Carlson, J.R. The Diverse Small Proteins Called Odorant-Binding Proteins. R. Soc. Open Biol. 2018, 8, 180208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abendroth, J.A.; Moural, T.W.; Wei, H.; Zhu, F. Roles of Insect Odorant Binding Proteins in Communication and Xenobiotic Adaptation. Front. Insect Sci. 2023, 3, 1274197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mam, B.; Karpe, S.D.; Sowdhamini, R. Minus-C Subfamily Has Diverged from Classic Odorant-Binding Proteins in Honeybees. Apidologie 2023, 54, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Sharma, D.; Choudhary, K.; Kumari, P.; Ruchika, K.; Yangchan, J.; Kumar, S. Insight into Insect Odorant Binding Proteins: An Alternative Approach for Pest Management. J. Nat. Pestic. Res. 2024, 8, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, W.S. Odorant Reception in Insects: Roles of Receptors, Binding Proteins, and Degrading Enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.-C.; Li, D.-Z.; Zhou, A.; Yi, S.-C.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.-Q. Predicted Structure of a Minus-C OBP from Batocera Horsfieldi (Hope) Suggests an Intermediate Structure in Evolution of OBPs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hou, M.; Liang, C.; Xu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Z. Role of Odorant Binding Protein C12 in the Response of Tribolium castaneum to Chemical Agents. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 201, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.-H.; Wang, C.-Q.; Li, K.-B.; Cao, Y.-Z.; Peng, Y.; Feng, H.-L.; Yin, J. Molecular Characterization of Sex Pheromone Binding Proteins from Holotrichia Oblita (Coleoptera: Scarabaeida). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, K. Minus-C Odorant Binding Protein TcasOBP7G Contributes to Reproduction and Defense against Phytochemical in the Red Flour Beetle, Tribolium castaneum. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2023, 26, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wen, Z.; Liu, S.-W.; Zhang, L.; Finley, C.; Lee, H.-J.; Fan, H.-J.S. Overview of AlphaFold2 and Breakthroughs in Overcoming Its Limitations. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 176, 108620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, C.; Liu, D. Analyses of Structural Dynamics Revealed Flexible Binding Mechanism for the Agrilus Mali Odorant Binding Protein 8 towards Plant Volatiles. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 1642–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Nakano-Baker, O.; Godin, D.; MacKenzie, D.; Sarikaya, M. iOBPdb a Database for Experimentally Determined Functional Characterization of Insect Odorant Binding Proteins. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.-S.; Li, R.-M.; Xue, S.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Wang, J.-S.; Zhang, K.-P. Odorant Binding Protein C17 Contributes to the Response to Artemisia Vulgaris Oil in Tribolium castaneum. Front. Toxicol. 2021, 3, 627470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, R. Odorant Binding Protein C12 Is Involved in the Defense against Eugenol in Tribolium castaneum. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 179, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Guo, M.; Yu, W.; Miao, W.; Ya, H.; Liu, D.; Li, R.; Zhang, K. Odorant Binding Protein TcOBPC02 Contributes to Phytochemical Defense in the Red Flour Beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Entomol. Res. 2024, 54, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montino, A.; Balakrishnan, K.; Dippel, S.; Trebels, B.; Neumann, P.; Wimmer, E.A. Mutually Exclusive Expression of Closely Related Odorant-Binding Proteins 9A and 9B in the Antenna of the Red Flour Beetle Tribolium castaneum. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, M.; Fuchs, P.F.; Sowdhamini, R.; Offmann, B. Insights on pH-Dependent Conformational Changes of Mosquito Odorant Binding Proteins by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2014, 32, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, P.; Iovinella, I.; Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Dani, F.R. Beyond Chemoreception: Diverse Tasks of Soluble Olfactory Proteins in Insects. Biol. Rev. 2017, 93, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, A.Q.; Ryu, J.; Del Mármol, J. Structural Basis of Odor Sensing by Insect Heteromeric Odorant Receptors. Science 2024, 384, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wang, B.; Guan, Z.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cao, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Gong, Z. Structural Basis for Odorant Recognition of the Insect Odorant Receptor OR-Orco Heterocomplex. Science 2024, 384, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engsontia, P.; Sanderson, A.P.; Cobb, M.; Walden, K.K.; Robertson, H.M.; Brown, S. The Red Flour Beetle’s Large Nose: An Expanded Odorant Receptor Gene Family in Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 38, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterwick, J.A.; Del Mármol, J.; Kim, K.H.; Kahlson, M.A.; Rogow, J.A.; Walz, T.; Ruta, V. Cryo-EM Structure of the Insect Olfactory Receptor Orco. Nature 2018, 560, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Jafari, S.; Pask, G.; Zhou, X.; Reinberg, D.; Desplan, C. Evolution, Developmental Expression and Function of Odorant Receptors in Insects. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223, jeb208215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Ma, Y.-F.; Wang, M.-M.; Wang, H.; Dewer, Y.; Abd El-Ghany, N.M.; Chen, G.-L.; Yang, G.-Q.; Zhang, F.; He, M. Silencing the Odorant Coreceptor (Orco) Disrupts Sex Pheromonal Communication and Feeding Responses in Blattella germanica: Toward an Alternative Target for Controlling Insect-transmitted Human Diseases. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latief, M. A Family of Chemoreceptors in Tribolium castaneum (Tenebrionidae: Coleoptera). PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Otake, J.; Mitsuno, H.; Ozaki, K.; Kanzaki, R.; Chieng, A.C.-T.; Hee, A.K.-W.; Nishida, R.; Ono, H. Functional Characterization of Olfactory Receptors in the Oriental Fruit Fly Bactrocera dorsalis That Respond to Plant Volatiles. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 101, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassau, S.; Krieger, J. The Role of SNMPs in Insect Olfaction. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Xue, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Li, B. Odorant-Binding Proteins Contribute to the Defense of the Red Flour Beetle, Tribolium castaneum, against Essential Oil of Artemisia Vulgaris. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, B.; Qin, Z.; Kader, A.; Song, B.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W. Identification of Candidate Olfactory Genes in Scolytus Schevyrewi Based on Transcriptomic Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 717698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, G.; Yi, X. FoxO Directly Regulates the Expression of Odorant Receptor Genes to Govern Olfactory Plasticity upon Starvation in Bactrocera dorsalis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 153, 103907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, P.T.; Casasa, S.; Moczek, A.P. Assessing the Evolutionary Lability of Insulin Signalling in the Regulation of Nutritional Plasticity across Traits and Species of Horned Dung Beetles. J. Evol. Biol. 2023, 36, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stočes, D.; Šipoš, J. Multilevel Analysis of Ground Beetle Responses to Forest Management: Integrating Species Composition, Morphological Traits and Developmental Instability. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, K.; Benton, R. Olfactory Receptor Gene Regulation in Insects: Multiple Mechanisms for Singular Expression. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 738088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Länger, Z.M.; Israel, E.; Engelhardt, J.; Kalita, A.I.; Keller Valsecchi, C.I.; Kurtz, J.; Prohaska, S.J. Multiomics Reveal Associations between CpG Methylation, Histone Modifications and Transcription in a Species That Has Lost DNMT3, the Colorado Potato Beetle. J. Exp. Zool. Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2025, 344, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güney, G.; Schmitt, K.; Zicola, J.; Toprak, U.; Rostás, M.; Scholten, S.; Cedden, D. The MicroRNA Pathway Regulates Obligatory Aestivation in a Flea Beetle. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, Y.; Tian, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, S. Transcriptome-Wide Evaluation Characterization of microRNAs and Assessment of Their Functional Roles as Regulators of Diapause in Ostrinia Furnacalis Larvae (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Insects 2024, 15, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsouri, A.; Douris, V. The Role of Chemosensory Proteins in Insecticide Resistance: A Review. Insects 2025, 16, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, M.; Eleftherianos, I.; Mohamed, A.; Cao, Y.; Song, B.; Zang, L.-S.; Jia, C.; Bian, J.; Keyhani, N.O. An Odorant Binding Protein Is Involved in Counteracting Detection-Avoidance and Toll-Pathway Innate Immunity. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 48, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, F.; Flisi, S.; Careri, M.; Riboni, N.; Resimini, S.; Sala, A.; Conti, V.; Mattarozzi, M.; Taddei, S.; Spadini, C. Vertebrate Odorant Binding Proteins as Antimicrobial Humoral Components of Innate Immunity for Pathogenic Microorganisms. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.C.; Gordon, B.; McDonough-Goldstein, C.E.; Misra, S.; Findlay, G.D.; Clark, A.G.; Wolfner, M.F. The Seminal Odorant Binding Protein Obp56g Is Required for Mating Plug Formation and Male Fertility in Drosophila Melanogaster. Elife 2023, 12, e86409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yang, L.; Wu, Z.; Chen, M.; Lu, Y. Volatiles of the Predator Xylocoris Flavipes Recognized by Its Prey Tribolium Castaneum (Herbst) and Oryzaephilus Surinamensis (Linne) as Escape Signals. Insects 2024, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajaro-Castro, N.; Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Neurotoxic Effects of Linalool and β-Pinene on Tribolium castaneum Herbst. Molecules 2017, 22, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, D.; Zhong, J.; Wen, L.; Yu, X. The dsRNA Delivery, Targeting and Application in Pest Control. Agronomy 2023, 13, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, Q.; Lin, X.; Smagghe, G. Recent Progress in Nanoparticle-Mediated RNA Interference in Insects: Unveiling New Frontiers in Pest Control. J. Insect Physiol. 2025, 167, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolge, H.; Kadam, K.; Ghormade, V. Chitosan Nanocarriers Mediated dsRNA Delivery in Gene Silencing for Helicoverpa Armigera Biocontrol. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 189, 105292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Chai, L.; Chang, B.H.; Malak, M.; El Wakil, A.; Moussian, B.; Zhao, Z.; Zeng, Z. Chitosan Nanoparticle-mediated Delivery of dsRNA for Enhancing RNAi Efficiency in Locusta migratoria. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 87, 5260–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurot, C.; Brenet, S.; Buhot, A.; Barou, E.; Belloir, C.; Briand, L.; Hou, Y. Highly Sensitive Olfactory Biosensors for the Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds by Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 123, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, G.D.; Esteves, C.; Moro, A.J.; Lima, J.C.; Barbosa, A.J.; Roque, A.C.A. An Odorant-Binding Protein Based Electrical Sensor to Detect Volatile Organic Compounds. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 411, 135726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.S.; Smith, D.P. Recent Insights into Insect Olfactory Receptors and Odorant-Binding Proteins. Insects 2022, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensana, A.; Achi, F. Analytical Performance of Functional Nanostructured Biointerfaces for Sensing Phenolic Compounds. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 196, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z. High-Efficiency Removal of Pyrethroids Using a Redesigned Odorant Binding Protein. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capo, A.; Cozzolino, S.; Cavallari, A.; Bruno, U.; Calabrese, A.; Pennacchio, A.; Camarca, A.; Staiano, M.; D’Auria, S.; Varriale, A. The Porcine Odorant-Binding Protein as a Probe for an Impedenziometric-Based Detection of Benzene in the Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffan, A.; Subandiyah, S.; Makino, H.; Watanabe, T.; Horiike, T. Evolutionary Analysis of the Highly Conserved Insect Odorant Coreceptor (Orco) Revealed a Positive Selection Mode, Implying Functional Flexibility. J. Insect Sci. 2018, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondón, J.J.; Moreyra, N.N.; Pisarenco, V.A.; Rozas, J.; Hurtado, J.; Hasson, E. Evolution of the Odorant-Binding Protein Gene Family in Drosophila. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 957247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.M.; Baits, R.L.; Walden, K.K.; Wada-Katsumata, A.; Schal, C. Enormous Expansion of the Chemosensory Gene Repertoire in the Omnivorous German Cockroach Blattella germanica. J. Exp. Zool. Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2018, 330, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venthur, H.; Zhou, J.-J. Odorant Receptors and Odorant-Binding Proteins as Insect Pest Control Targets: A Comparative Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| OBP | GenBank Accession | Subfamily | Primary Expression Tissues | Key Ligands/Inducers | Established Function(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TcOBPC11 | XM_962706 | Classic | Fat body, Malpighian tubules, Epidermis, Antennae | Artemisia vulgaris essential oil | Detoxification, Defense, Immunity | [35] |

| TcOBPC12 | NP_001107842.1 | Classic | Epidermis, Fat body, Antennae | Eugenol, Various chemical agents, Insecticides | Detoxification, Defense, Immunity | [21] |

| TcOBPC17 | XP_008194483.1 | Classic | Head, Fat body, Epidermis, Hemolymph | Artemisia vulgaris essential oil | Detoxification, Defense | [20] |

| TcOBPC02 | - | Classic | Head, Epidermis, Hemolymph | Eucalyptol | Phytochemical Defense | [22] |

| TcasOBP9A | NP_001107850.1 | Classic | Antennae | General odorants (e.g., green leaf volatiles) | Olfaction (General Volatile Detection) | [23] |

| TcasOBP9B | NP_001107851.1 | Classic | Antennae | General odorants (e.g., green leaf volatiles) | Olfaction (General Volatile Detection) | [23] |

| TcasOBP7G | - | Minus-C | Reproductive tissues, Antennae | Juvenile Hormone III, Phytochemicals | Reproduction, Defense, Immunity | [16] |

| Strategy | Target OBP(s) | Approach/Method | Key Finding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNAi-mediated lethality enhancement | TcOBPC11, TcOBPC12, TcOBPC17 | Larval dsRNA injection or feeding | Knockdown significantly increases mortality when larvae are subsequently exposed to eugenol or Artemisia vulgaris essential oil (mortality significantly higher than control). | [20,21,35] |

| TcOBPC02 | Larval dsRNA injection | Knockdown increases the susceptibility of larvae to eucalyptol. | [22] | |

| Proof-of-concept synergist | TcOBPC12 | In silico docking and fluorescence competition binding assays | Docking and fluorescence competition identified several ligands with strong micromolar affinity to TcOBPC12; proposed as candidate synergists against eugenol, but no in vivo insecticidal tests have been performed. | [14,21] |

| Antennal sensitivity enhancement | TcOBP9A, TcOBP9B | Electroantennography (EAG) + RNAi | Knockdown of TcOBP9A or TcOBP9B significantly reduces antennal responses to several food-related volatiles (e.g., 2-hexanone, (E)-2-heptenal, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one), indicating that these OBPs enhance odor detection at the antennal level; behavioral attraction assays were not performed. | [23] |

| Behavioral repellence (predator-derived) | Not directly via OBP blockade | Exposure to Xylocoris flavipes volatiles | Volatiles emitted by the predator X. flavipes, particularly linalool and geraniol, significantly reduce the orientation of T. castaneum towards food sources and act as potent spatial repellents in laboratory olfactometer assays; no OBP-based mechanism has been validated. | [49,50] |

| Application Field | Insect OBP(s) | Platform/Technique | Actual Reported Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene-based bioelectronic nose prototype | TcOBP9A, TcOBP9B (preliminary) | Graphene/reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) field-effect transistor (FET) | Recombinant TcOBP9A/B immobilized on graphene-based FET devices show reproducible electrical responses to model volatiles such as sulcatone and (S)-(+)-3-octanol in buffer; proposed as a proof-of-concept olfactory biosensor, but no food-matrix or field applications have been reported. | [56,57,58] |

| Fluorescence binding assay/future nanosensor | TcOBPC12 (preliminary) | Solution fluorescence quenching | Intrinsic fluorescence quenching assays demonstrate binding of eugenol and related phenolic/terpenoid compounds to TcOBPC12 in vitro; the protein has been suggested as a candidate recognition element for future nanosensors, but no immobilized sensor device has yet been reported. | [21] |

| Environmental pollutant removal (non-T. castaneum) | Porcine and lepidopteran OBPs | OBPs immobilized on biopolymers | Laboratory-scale studies with porcine and lepidopteran OBPs demonstrate up to ~90% removal of phenolic pollutants in aqueous systems; no experimental bioremediation has been performed with T. castaneum OBPs. | [59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Z. Odorant Binding Proteins in Tribolium castaneum: Functional Diversity and Emerging Applications. Insects 2025, 16, 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121250

Wang L, Lu Y, Zhao Z. Odorant Binding Proteins in Tribolium castaneum: Functional Diversity and Emerging Applications. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121250

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lei, Yujie Lu, and Zongpei Zhao. 2025. "Odorant Binding Proteins in Tribolium castaneum: Functional Diversity and Emerging Applications" Insects 16, no. 12: 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121250

APA StyleWang, L., Lu, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2025). Odorant Binding Proteins in Tribolium castaneum: Functional Diversity and Emerging Applications. Insects, 16(12), 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121250