Chlorination Is Ineffective at Eliminating Insects from Wastewater: A Case Study Using Ceratitis capitata

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing and Egg Collection

2.2. Chlorine Solution Preparation and Experimental Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

- -

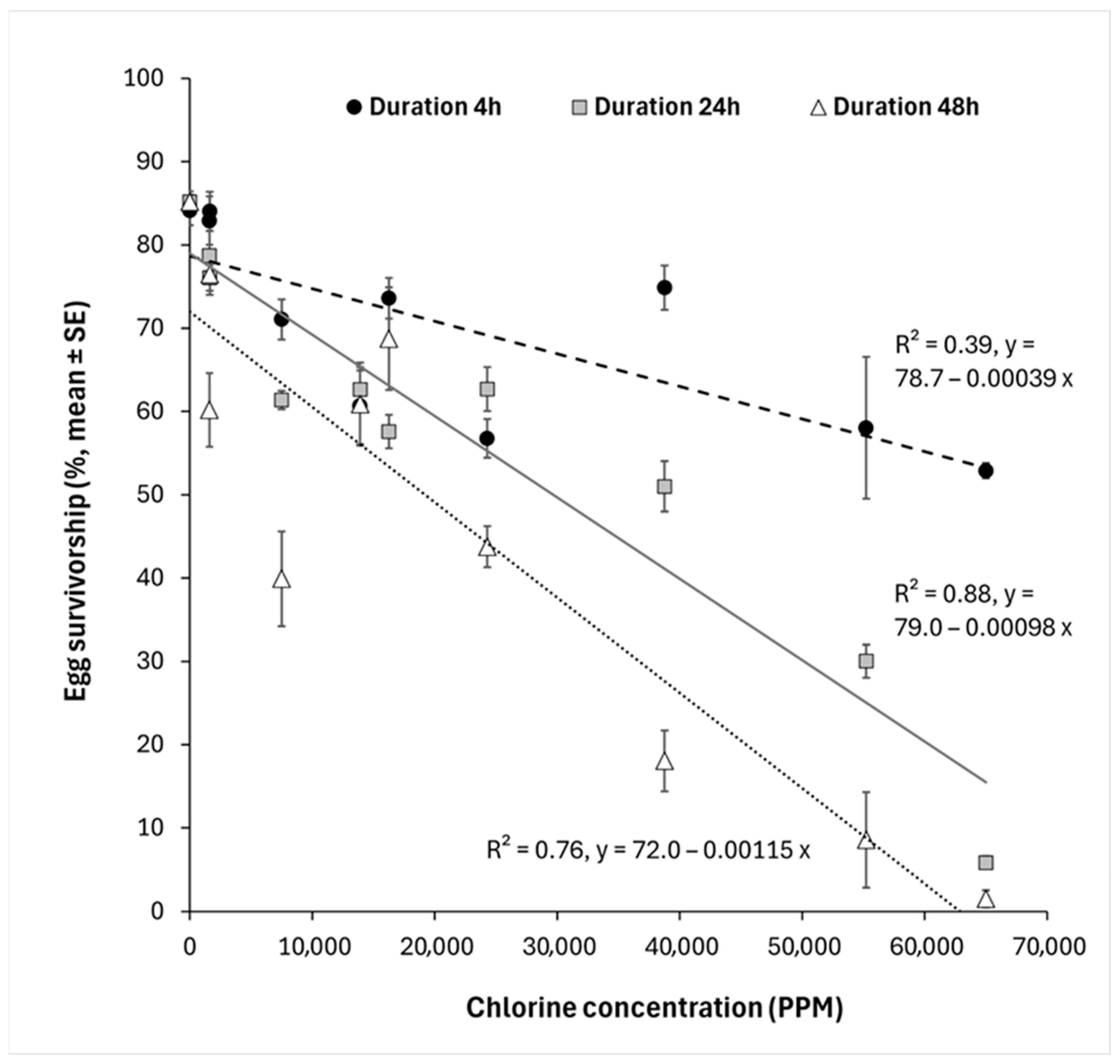

- For 4 h, % egg survivorship = 78.7 − 0.00039 × chlorine concentration, R2 = 0.39, F1,48 = 32.5, p < 0.0001. LC50 value = 71,509 ppm; LC90 value = 192,769 ppm.

- -

- For 24 h, % egg survivorship = 79.0 − 0.00098 × chlorine concentration, R2 = 0.88, F1,48 = 347.8, p < 0.0001. LC50 value = 27,048 ppm. LC90 value = 73,420 ppm.

- -

- For 48 h, % egg survivorship = 72.0 − 0.00115 × chlorine concentration, R2 = 0.76, F1,48 = 158.2, p < 0.0001. LC50 value = 16,987 ppm. LC90 value = 53,214 ppm.

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bull, R.J.; Birnbaum, L.; Cantor, K.P.; Rose, J.B.; Butterworth, B.E.; Pegram, R.; Tuomisto, J. Water chlorination: Essential process or cancer hazard? Toxicol. Sci. 1995, 28, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.M.; Fernandez, F.; Malats, N.; Grimalt, J.O.; Kogevinas, M. Meta-analysis of studies on individual consumption of chlorinated drinking water and bladder cancer. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Huang, J.; Min, F.; Zhong, H.; Ling, J.; Kang, Q.; Li, Z.; Wen, L. Characterization of Disinfection By-Products Originating from Residual Chlorine-Based Disinfectants in Drinking Water Sources. Toxics 2024, 12, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, T.; Coulomb, B.; Boudenne, J.-L. Occurrence, origin, and toxicity of disinfection byproducts in chlorinated swimming pools: An overview. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, A.J.; Amador, M.; Felix, G.; Acevedo, V.; Barrera, R. Evaluation of Household Bleach as an Ovicide for the Control of Aedes aegypti. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2015, 31, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.A. Efficacy of Australian quarantine procedures against the mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2001, 17, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shahen, M.; El-Wahsh, H.; Ramadan, C.; Hegazi, M.; Al-Sharkawi, I.; Seif, A. A comparison of the toxicity of calcium and sodium hypochlorite against Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. J. Environ. Sci. Curr. Res. 2020, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayaturrahman, H.; Kwon, H.J.; Bao, Y.; Peera, S.G.; Lee, T.G. Assessing the Efficacy of Coagulation (Al3+) and Chlorination in Water Treatment Plant Processes: Inactivating Chironomid larvae for Improved Tap Water Quality. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-B.; Cui, F.-Y.; Zhang, J.-S.; Xu, F.; Liu, L.-J. Inactivation of Chironomid larvae with chlorine dioxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 142, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.Q.; Burt, A.; Capurro, M.L.; De Barro, P.; Handler, A.M.; Hayes, K.R.; Marshall, J.M.; Tabachnick, W.J.; Adelman, Z.N. Recommendations for laboratory containment and management of gene drive systems in arthropods. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018, 18, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondeville, E.; Failloux, A.-B.; Simard, F.; Volf, P.; Crisanti, A.; Haghighat-Khah, R.E.; Busquets, N.; Abad, F.X.; Wilson, A.J.; Bellini, R. Infravec2 guidelines for the design and operation of containment level 2 and 3 insectaries in Europe. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoback, W.W.; Stanley, D.W. Insects in hypoxia. J. Insect Physiol. 2001, 47, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, J.D. Surviving a flood: Effects of inundation period, temperature and embryonic development stage in locust eggs. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2015, 105, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunti, G.; Benelli, G.; Campolo, O.; Canale, A.; Kapranas, A.; Liedo, P.; De Meyer, M.; Nestel, D.; Ruiu, L.; Scolari, F. Management of the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata: Past, present, and future. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 1241–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Staples, D.; Díaz-Fleischer, F.; Montoya, P. The sterile insect technique: Success and perspectives in the Neotropics. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, C.; Hendrichs, J.; Vreysen, M.J. Development and improvement of rearing techniques for fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) of economic importance. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2014, 34, S1–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaada, D.S.Y.; Ben-Yosef, M.; Yuval, B.; Jurkevitch, E. The host fruit amplifies mutualistic interaction between Ceratitis capitata larvae and associated bacteria. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardonnet, F.; Blanchet, A.; Hurtrel, B.; Marini, F.; Smith, L. Mass-rearing optimization of the parasitoid Psyttalia lounsburyi for biological control of the olive fruit fly. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, C.; Ramírez, E.; Wornoayporn, V.; Islam, S.M.; Ahmad, S. A protocol for storage and long-distance shipment of Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) eggs. I. Effect of temperature, embryo age, and storage time on survival and quality. Fla. Entomol. 2007, 90, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Retnakaran, A. Evaluating single treatment data using Abbott’s formula with reference to insecticides. J. Econ. Entomol. 1985, 78, 1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.A. Toxic effects of residual chlorine on larvae of Hydropsyche pellucidula (Trichoptera, Hydropsychidae): A proposal of biological indicator. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1991, 47, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-S.; Kim, G.-T.; Ahn, K.-S.; Shin, S.-S. Effects of disinfectants on larval development of Ascaris suum eggs. Korean J. Parasitol. 2016, 54, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.M.; Hill, V.R.; Arrowood, M.J.; Beach, M.J. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum under chlorinated recreational water conditions. J. Water Health 2008, 6, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, D.; Ruggeri, L.; Trentini, M. The use of sodium hypochlorite as ovicide against Aedes albopictus. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2006, 22, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, C.; Fernandez, E.A.; Chan, A.S.; Lozano, R.C.; Leontsini, E.; Winch, P.J. La Untadita: A procedure for maintaining washbasins and drums free of Aedes aegypti based on modification of existing practices. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998, 58, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, D.; Johnson, E.; Abhinay, A.; Jayabalan, R.; Mishra, M. A protocol to generate germ free Drosophila for microbial interaction studies. Adv. Tech. Biol. Med. S 2015, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navis, S.; Waterkeyn, A.; Voet, T.; De Meester, L.; Brendonck, L. Pesticide exposure impacts not only hatching of dormant eggs, but also hatchling survival and performance in the water flea Daphnia magna. Ecotoxicology 2013, 22, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sil, T.B.; Malyshev, D.; Aspholm, M.; Andersson, M. Boosting hypochlorite’s disinfection power through pH modulation. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukubuiwe, A.C.; Ojianwuna, C.C.; Olayemi, I.K.; Arimoro, F.O.; Ukubuiwe, C.C. Quantifying the roles of water pH and hardness levels in development and biological fitness indices of Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2020, 81, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabots, G. Un système sécurisé de traitement thermique des eaux usées dans des locaux confinés d’élevage d’insectes règlementés. Cahier des Techniques de l’INRA 2017, 25–33. Available online: https://revue-novae.fr/article/view/8811 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

| Chlorine Concentration (PPM) | Immersion Duration 4 h | Immersion Duration 24 h | Immersion Duration 48 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 ± 3.0 a | 0 ± 1.3 a | 0 ± 2.2 a |

| 1600–1625 | 0.7 ± 3.8 a | 9.2 ± 3 a | 19.7 ± 4.2 ab |

| 7490 | 15.6 ± 3.4 ab | 27.9 ± 1.5 b | 53.2 ± 6.7 bc |

| 13,900 | 27.8 ± 5.7 b | 26.5 ± 2.8 b | 28.5 ± 6.0 ab |

| 16,250 | 12.5 ± 3.4 ab | 32.4 ± 2.4 b | 19.4 ± 7.4 ab |

| 24,280 | 32.5 ± 3.1 b | 26.4 ± 3.2 b | 48.6 ± 2.9 bc |

| 38,760 | 10.9 ± 3.7 ab | 40.1 ± 3.6 b | 78.9 ± 4.2 cd |

| 55,220 | 31.0 ± 10.2 b | 64.8 ± 2.4 c | 89.9 ± 6.7 d |

| 65,000 | 37.1 ± 1.7 b | 93.2 ± 0.9 d | 98.2 ± 1.2 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kafunda, F.; Blanchet, A.; Desurmont, G.A. Chlorination Is Ineffective at Eliminating Insects from Wastewater: A Case Study Using Ceratitis capitata. Insects 2025, 16, 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121213

Kafunda F, Blanchet A, Desurmont GA. Chlorination Is Ineffective at Eliminating Insects from Wastewater: A Case Study Using Ceratitis capitata. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121213

Chicago/Turabian StyleKafunda, Flora, Arnaud Blanchet, and Gaylord A. Desurmont. 2025. "Chlorination Is Ineffective at Eliminating Insects from Wastewater: A Case Study Using Ceratitis capitata" Insects 16, no. 12: 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121213

APA StyleKafunda, F., Blanchet, A., & Desurmont, G. A. (2025). Chlorination Is Ineffective at Eliminating Insects from Wastewater: A Case Study Using Ceratitis capitata. Insects, 16(12), 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121213