Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Insect Cultural Services: How Do Insects Help Shape Us and Our Societies?

2.1. Insects in Traditional Beliefs and Mythology

2.2. Insects in Fashion and Design

2.3. Insects in Media

2.4. Insects in Recreation and Hobbies

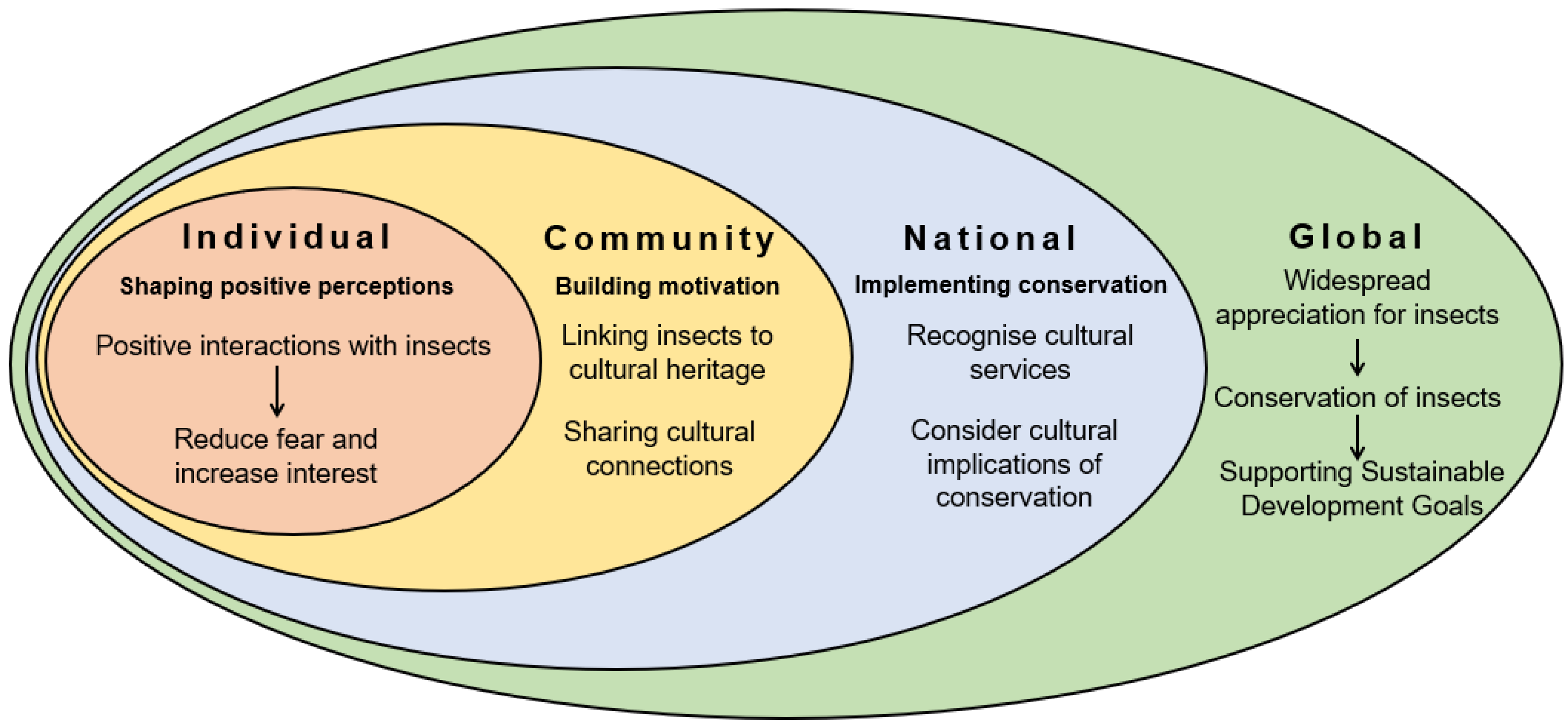

3. Bringing Insects Back into Culture: A Multi-Level Framework

- (a)

- Individual-level actions

- (b)

- Community level actions

- (c)

- National-level actions

- (d)

- Global-level actions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, J.A.; Hortal, J.; Azcárate, F.M.; Berg, M.P.; Bonada, N.; Briones, M.J.; Del Toro, I.; Goulson, D.; Ibanez, S.; Landis, D.A.; et al. Research trends in ecosystem services provided by insects. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2018, 26, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P. Habitats Directive species lists: Urgent need of revision. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2011, 5, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, C.; Jay-Robert, P.; Vergnes, A. Bias and perspectives in insect conservation: A European scale analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 215, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colléony, A.; Clayton, S.; Couvet, D.; Jalme, M.S.; Prévot, A.-C. Human preferences for species conservation: Animal charisma trumps endangered status. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, B.; Montes, C.; Benayas, J. The non-economic motives behind the willingness to pay for biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 139, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon, A.M. Does animal charisma influence conservation funding for vertebrate species under the US Endangered Species Act? Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2019, 21, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, M.R.; Burnett, N.J.; Braun, D.C.; Suski, C.D.; Hinch, S.G.; Cooke, S.J.; Kerr, J.T. Taxonomic bias and international biodiversity conservation research. FACETS 2017, 1, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammola, S.; Riccardi, N.; Prié, V.; Correia, R.; Cardoso, P.; Lopes-Lima, M.; Sousa, R. Towards a taxonomically unbiased European Union biodiversity strategy for 2030. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2020, 287, 20202166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Lindström, S.A.M.; Herbertsson, L.; Rundlöf, M.; Bommarco, R.; Smith, H.G. Experimental evidence that honeybees depress wild insect densities in a flowering crop. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2016, 283, 20161641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, C.M.; Laws, A.N. Insects as a piece of the puzzle to mitigate global problems: An opportunity for ecologists. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2018, 26, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangles, O.; Casas, J. Ecosystem services provided by insects for achieving sustainable development goals. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 35, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowalter, T.D. Insects and Sustainability of Ecosystem Services, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, P.; Barton, P.S.; Birkhofer, K.; Chichorro, F.; Deacon, C.; Fartmann, T.; Fukushima, C.S.; Gaigher, R.; Habel, J.C.; Hallmann, C.A.; et al. Scientists’ warning to humanity on insect extinctions. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.; Erwin, T.L.; Borges, P.A.; New, T.R. The seven impediments in invertebrate conservation and how to overcome them. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 2647–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.P.R.; Koma, Z.; WallisDeVries, M.F.; Kissling, W.D. Identifying fine-scale habitat preferences of threatened butterflies using airborne laser scanning. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Brandl, R. Assessing biodiversity by remote sensing in mountainous terrain: The potential of LiDAR to predict forest beetle assemblages. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbuena, R.; O’Connor, B.; Zellweger, F.; Simonson, W.; Vihervaara, P.; Maltamo, M.; Silva, C.; Almeida, D.; Danks, F.; Morsdorf, F.; et al. Standardizing Ecosystem Morphological Traits from 3D Information Sources. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegoraro, L.; Hidalgo, O.; Leitch, I.J.; Pellicer, J.; Barlow, S.E. Automated video monitoring of insect pollinators in the field. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2020, 4, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samways, M.J.; Barton, P.S.; Birkhofer, K.; Chichorro, F.; Deacon, C.; Fartmann, T.; Fukushima, C.S.; Gaigher, R.; Habel, J.C.; Hallmann, C.A.; et al. Solutions for humanity on how to conserve insects. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowalter, T.; Noriega, J.; Tscharntke, T. Insect effects on ecosystem services—Introduction. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2018, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, S.A.; Wainwright, W.A.; Christie, M. The application of an ecosystem services framework to estimate the economic value of dung beetles to the U.K. cattle industry. Ecol. Èntomol. 2015, 40, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Sumaila, U.R. A global estimate of benefits from ecosystem-based marine recreation: Potential impacts and implications for management. J. Bioecon. 2010, 12, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, J.; Albert, C.; Hermes, J.; Von Haaren, C. Assessing and quantifying offered cultural ecosystem services of German river landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabana, D.; Ryfield, F.; Crowe, T.P.; Brannigan, J. Evaluating and communicating cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcu, A.I.; Hanspach, J.; Abson, D.; Fischer, J. Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Literature Review and Prospects for Future Research. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P. Effects of sense of place on responses to environmental impacts. Appl. Geogr. 1998, 18, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhorst, A.M.; Hoon, C.; le Rutte, R.; de Snoo, G. There is an I in nature: The crucial role of the self in nature conservation. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, S.; Law, G.; Cini, A. Why we love bees and hate wasps. Ecol. Èntomol. 2018, 43, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of Neighborhood Nature: The Benefits for Mental Health of Living with Nature. BioScience 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Weinstein, P. Ancient Egyptians’ Atypical Relationship with Invertebrates. Soc. Anim. 2019, 27, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insect Fact and Folklore. Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 1954, 47, 540–541. [CrossRef]

- Cherry, R.H. Insect Names Derived from Greek and Roman Mythology. Am. Èntomol. 1997, 43, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramos Elorduy, J. Insects: A Hopeful Food Source. In Ecological Implications of Minilivestock: Role of Rodents, Frogs, Snails and Insects for Sustainable Development; Paoletti, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J.; Moreno, J.M.P.; I Vázquez, A.; Landero, I.; Oliva-Rivera, H.; Camacho, V.H.M. Edible Lepidoptera in Mexico: Geographic distribution, ethnicity, economic and nutritional importance for rural people. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J. Energy Supplied by Edible Insects from Mexico and their Nutritional and Ecological Importance. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2008, 47, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J. Insects: A sustainable source of food? Ecol. Food Nutr. 1997, 36, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faast, R.; Clarke, P.A.; Taylor, G.S.; Salagaras, R.L.; Weinstein, P. Indigenous Use of Lerps in Australia: So Much More Than a Sweet Treat. J. Ethnobiol. 2020, 40, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, I.D. The biology of the Psylloidea (Homoptera): A review. Bull. Èntomol. Res. 1974, 64, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong, C.K.; Addo-Bediako, A.; Potgieter, M.J.; Wessels, D.C.J. Nymphal Behaviour and Lerp Construction in the Mopane PsyllidRetroacizzia mopani(Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Afr. Invertebr. 2010, 51, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilby, A.; McKellar, J.; Beaton, C. The structure of lerps: Carbohydrate, lipid, and protein components. J. Insect Physiol. 1976, 22, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.; Mourits, M.C.M.; Van Der Werf, W.; Lansink, A.G.J.M.O.; Werf, W. Economic justification for quarantine status—The case study of ‘CandidatusLiberibacter solanacearum’ in the European Union. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, A.B. Insects—A mistake in God’s creation? Tharu farmers’ perception and knowledge of insects: A case study of Gobardiha Village Development Committee, Dang-Deukhuri, Nepal. Agric. Hum. Values 2003, 20, 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeser, M. Silk, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Padaki, N.; Das, B.; Basu, A. Advances in understanding the properties of silk. In Advances in Silk Science and Technology; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. The Termination of the Silk Road: A Study of the History of the Silk Road from a New Perspective. Asian Rev. World Hist. 2020, 8, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, L. The Creative Influence of History in Fashion Practice: The Legacy of the Silk Road and Chinese-Inspired Culture-Led Design. Fash. Pr. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, M. Silk in Antiquity: World History Encyclopedia. Available online: https://www.ancient.eu/Silk/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Artsor Chu Tomb: Brown-Colored Embroidered Silk with Rectangular Pattern. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.13896018 (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Ranavaada, V.P.; Karolia, A. National Fashion Identities of the Indian Sari. Int. J. Text. Fash. Technol. 2016, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 20 December 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/61/189 (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Sohn, K.-W. Conservation Status of Sericulture Germplasm Resources in the World-II. Conservation Status of Silkworm (Bombyx Mori) Genetic Resources in the World; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UN Comtrade China. Imports and Exports. World. Silk. Value (US$) and Value Growth, YoY (%). 2008–2019. Available online: https://trendeconomy.com/data/h2/China/50 (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Floyd, J. Insect Illustration, a Multi-legged History. J. Guild. Nat. Sci. Illus. 2009, 41, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dicke, M. Insects in Western Art. Am. Èntomol. 2000, 46, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachat, S.R. Insect Biodiversity in Meiji and Art Nouveau Design. Am. Èntomol. 2015, 61, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane, S.P.; Ramaswamy, S.S.; Raja, S.V. Insect architecture: Structural diversity and behavioral principles. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 42, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, C.T.; Clark, R.M.; Moore, D.; Overson, R.P.; Penick, C.A.; Smith, A.A. Social insects inspire human design. Biol. Lett. 2010, 6, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, P.; Huang, G.; Feng, S.; Shen, C.; Han, B.; Zhang, X.; Jin, F.; Xu, F.; et al. Bioinspired engineering of honeycomb structure—Using nature to inspire human innovation. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 74, 332–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorb, S.N.; Gorb, E.V. Insect-inspired architecture to build sustainable cities. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 40, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobus, L.M.; Macadam, C.R.; Sartori, M. Mayflies (Ephemeroptera) and Their Contributions to Ecosystem Services. Insects 2019, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszás, F. Tisza Mayfly and ‘Tisza Blooming’ Become Hungaricums as National Values. Available online: https://hungarytoday.hu/tisza-mayfly-and-tisza-blooming-become-hungaricums-as-national-values/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Szent-Ivany, J.J.H.; Ujhary, E.I.V. Ephemeroptera in the regimen of some New Guinea people and in Hungarian folksongs. Eatonia 1973, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bálint, M.; Málnás, K.; Nowak, C.; Geismar, J.; Váncsa, É.; Polyák, L.; Lengyel, S.; Haase, P. Species History Masks the Effects of Human-Induced Range Loss—Unexpected Genetic Diversity in the Endangered Giant Mayfly Palingenia longicauda. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenbaum, M.R.; Leskosky, R.J. Movies, Insects. In Encyclopedia of Insects; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 668–674. [Google Scholar]

- EGSA Illinois. The Insect Fear Film Festival. Available online: https://publish.illinois.edu/uiuc-egsa/ifff/ (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Worsham, H.; Diepenbrok, L. Evaluating Scientific Content. Am. Biol. Teach. 2013, 75, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da-Silva, E.; Coelho, L.; Santos, E.; Rodas, T.; Miranda, G.; Araujo, T.; Carelli, A. Marvel and DC Characters Inspired By Insects. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. Res. 2014, 4, 10–36. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, J. Insects in Rock & Roll Music. Am. Èntomol. 2000, 46, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megu, K.; Chakravorty, J.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. An Ethnographic Account of the Role of Edible Insects in the Adi Tribe of Arunachal Pradesh, North-East India. In Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, E. Insects in the World of Fiction. Am. Entomol. 2013, 59, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maya, E.M.A. Documenting and Contextualizing Pjiekakjoo (Tlahuica) Knowledges though a Collaborative Research Project; University of Washington: Washington, DA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C. The NHBS Guide to Pond Dipping. Available online: https://www.nhbs.com/blog/nhbs-guide-pond-dipping (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Fančovičová, J.; Prokop, P. Effects of Hands-on Activities on Conservation, Disgust and Knowledge of Woodlice. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 14, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfelder, M.L.; Bogner, F.X. How to sustainably increase students’ willingness to protect pollinators. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 24, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, A.E.Z.; Dikow, T.; Moreau, C.S. Entomological Collections in the Age of Big Data. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2018, 63, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudic, K.L.; McFarland, K.P.; Oliver, J.C.; Hutchinson, R.A.; Long, E.C.; Kerr, J.T.; Larrivée, M. eButterfly: Leveraging Massive Online Citizen Science for Butterfly Conservation. Insects 2017, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.C.; Hilchey, K.G. A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: Issues and opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 176, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirson, G.; Tingley, D.; Spurgeon, J.; Radford, A. Economic evaluation of inland fisheries in England and Wales. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2001, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, G.W.; Cormier, S.M. Why care about aquatic insects: Uses, benefits, and services. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2015, 11, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, S. New streams of religion: Fly fishing as a lived, religion of nature. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 2007, 75, 896–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J. Pioneers and Pioneering: The Allure and Early Days of Saltwater Fly Fishing. Am. Fly Fish. 2012, 38. Available online: https://www.amff.org/pioneers-pioneering-allure-early-days-saltwater-fly-fishing/ (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Craig, P.J.; Alger, D.M.; Bennett, J.L.; Martin, T.P. The Transformative Nature of Fly-Fishing for Veterans and Military Personnel with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Ther. Recreat. J. 2020, 54, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.L.; Piatt, J.A.; Van Puymbroeck, M. Outcomes of a Therapeutic Fly-Fishing Program for Veterans with Combat-Related Disabilities: A Community-Based Rehabilitation Initiative. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, N.J.; Bixler, R.D. Beautiful Bugs, Bothersome Bugs, and FUN Bugs: Examining Human Interactions with Insects and Other Arthropods. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C.; Lu, C.-C.; Hwang, M.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Chou, C.-Y. Larvae phobia relevant to anxiety and disgust reflected to the enhancement of learning interest and self-confidence. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 42, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, L.L.; Berenbaum, H. A naturalistic examination of positive expectations, time course, and disgust in the origins and reduction of spider and insect distress. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.S.; Teel, T.L.; Solomon, J.; Weiss, J. Evolving systems of pro-environmental behavior among wildscape gardeners. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Byg, A.; Hartel, T.; Hurley, P.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Nagabhatla, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.M.; et al. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iceland, C.; Hanson, C.; Lewis, C. Identifying Important Ecosystem Goods and Services in Puget Sound: Draft Summary of Interviews and Research for the Puget Sound Partnership; Puget Sound Partnership: Olympia, Greece, 2008.

- A Wilson, M.; Howarth, R.B. Discourse-based valuation of ecosystem services: Establishing fair outcomes through group deliberation. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosanic, A.; Petzold, J. A systematic review of cultural ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palta, M.; du Bray, M.V.; Stotts, R.; Wolf, A.; Wutich, A. Ecosystem Services and Disservices for a Vulnerable Population: Findings from Urban Waterways and Wetlands in an American Desert City. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Klain, S.; Satterfield, T.; Basurto, X.; Bostrom, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Gould, R.K.; Halpern, B.S.; et al. Where are Cultural and Social in Ecosystem Services? A Framework for Constructive Engagement. BioScience 2012, 62, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A.; Fish, R.; Haines-Young, R.; Mourator, S.; Tratalos, J.; Stapleton, L.; Willis, C.; Coates, P.; Gibbons, S.; Leyshon, C.; et al. UK National Ecosystem Assessment Follow-on Phase, Technical Report: Cultural Ecosystem Services and Indicators; UNEP-WCMC, LWEC: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duffus, N.E.; Christie, C.R.; Morimoto, J. Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them. Insects 2021, 12, 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050377

Duffus NE, Christie CR, Morimoto J. Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them. Insects. 2021; 12(5):377. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050377

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuffus, Natalie E., Craig R. Christie, and Juliano Morimoto. 2021. "Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them" Insects 12, no. 5: 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050377

APA StyleDuffus, N. E., Christie, C. R., & Morimoto, J. (2021). Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them. Insects, 12(5), 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050377