Dust Deficiency in the Interacting Galaxy NGC 3077

Abstract

:1. Introduction

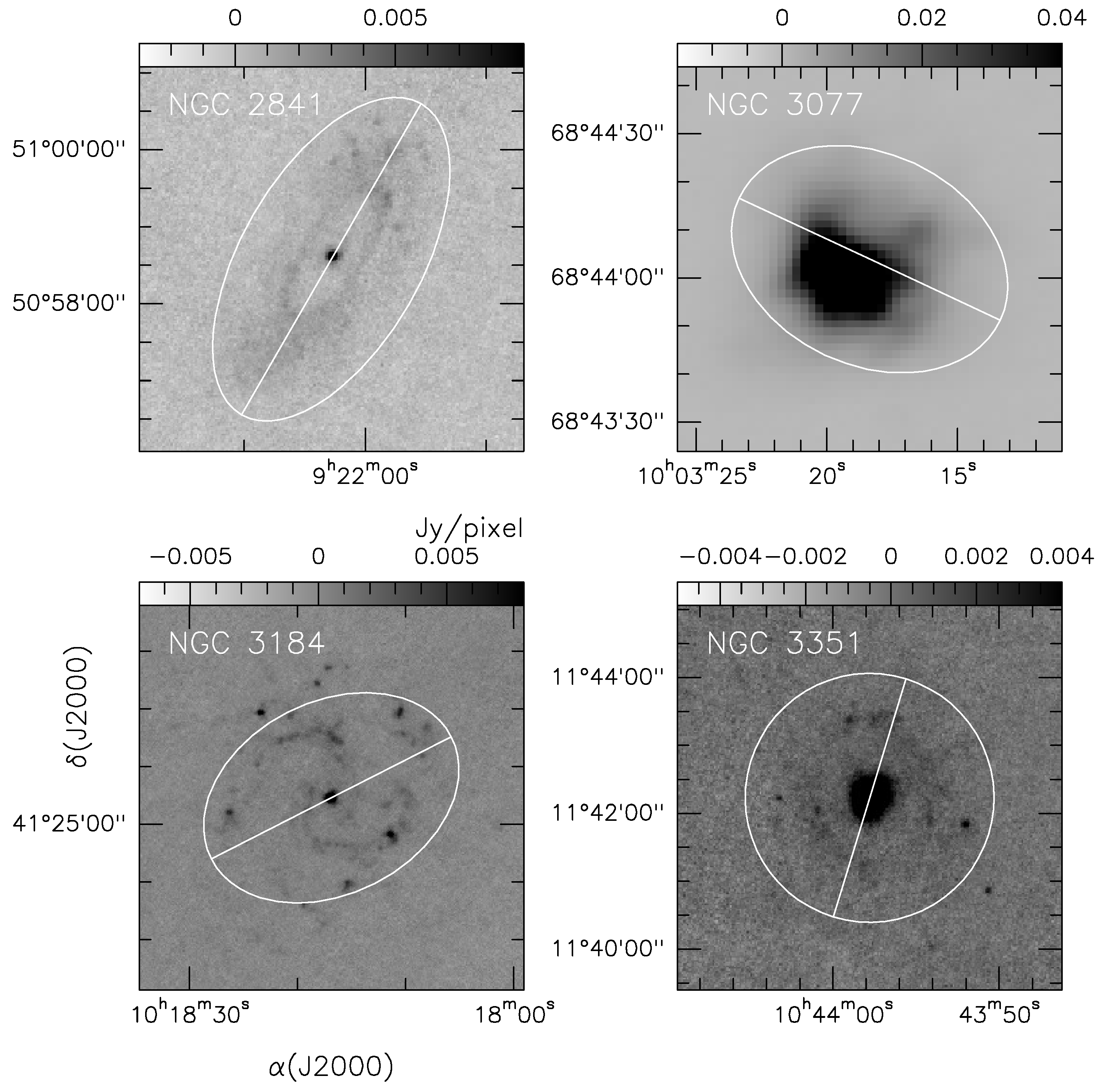

2. Infrared Data

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Infrared Flux Density

3.2. Dust Mass

3.3. Dust-To-Gas Ratio

4. Conclusions

- For the isolated NGC 2841, NGC 3184 and NGC 3351 galaxies, we find dust masses in the range of 6.5–9.1 × 10 M. The dust masses of these galaxies are a factor of ∼10 higher than the dust mass found for NGC 3077 affected by the tidal interactions of galaxies M81 and M82, indicating that NGC 3077 is a dust-deficient galaxy.

- NGC 3077 shows a dust-to-gas ratio of 17.5% that is much higher than the average value of 1.8% found for NGC 2841, NGC 3184 and NGC 3351. The ratio of 17.5% suggests that NGC 3077 is also deficient in H + HI gas, which has been stripped more efficiently than dust in this galaxy.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasmussen, J.; Ponman, T.; Verdes-Montenegro, L.; Yun, M.S.; Borthakur, S. Galaxy evolution in Hickson compact groups: The role of ram-pressure stripping and strangulation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 388, 1245–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L.; Mastropietro, C.; Wadsley, J.; Stadel, J; Moore, B. Simultaneous ram pressure and tidal stripping; how dwarf spheroidals lost their gas. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 369, 1021–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulsen, P.E.J. Transport processes and the stripping of cluster galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1982, 198, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, L.L.; Songaila, A. Thermal evaporation of gas within galaxies by a hot intergalactic medium. Nature 1977, 266, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, R.; Haynes, M.P. Gas deficiency in cluster galaxies: a comparison of nine clusters. Astrophys. J. 1985, 292, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanes, J.M.; Manrique, A.; García-Gómez, C.; González-Casado, G.; Giovanelli, R.; Haynes, M.P. The HI content of spirals. II. Gas deficiency in cluster galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2001, 548, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, C.; Bianchi, S.; Corbelli, E.; Giovanardi, C.; Hunt, L.; Bendo, G.J.; Boselli, A.; Cortese, L.; Magrini, L.; Zibetti, S.; et al. The Herschel Virgo Cluster Survey. XI. Environmental effects on molecular gas and dust in spiral disks. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 545, A75–A91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, L.; Bekki, K.; Boselli, A.; Catinella, B.; Ciesla, L.; Hughes, T.M.; Baes, M.; Bendo, G.J.; Boquien, M.; de Looze, I.; et al. The selective effect of environment on the atomic and molecular gas-to-dust ratio of nearby galaxies in the Herschel reference survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 459, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, K.M.; Leroy, A.K.; Walter, F.; Bolatto, A.D.; Crowall, K.V.; Draine, B.T.; Wilson, C.D.; Wolfire, M.; Calzetti, D.; Kennicutt, R.C.; et al. The CO-to-H2 Conversion Factor and Dust-to-Gas Ratio on Kiloparsec Scales in Nearby Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2013, 777, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, F.; Weiss, A.; Martin, C.; Scoville, N. The Interacting Dwarf Galaxy NGC 3077: The Interplay of Atomic and Molecular Gas with Violent Star Formation. Astron. J. 2002, 123, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennicutt, R.C.; Calzetti, D.; Aniano, G.; Appleton, P.; Armus, L.; Beirāo, P.; Bolatto, A.D.; Brandl, B.; Crocker, A.; Croxall, K. KINGFISH-Key Insights on Nearby Galaxies: A Far-Infrared Survey with Herschel: Survey Description and Image Atlas. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2011, 123, 1347–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.; Armijos-Abendaño, J.; Llerena, M.; Aldás, F. Upper limits to magnetic fields in the outskirts of galaxies. Galaxies 2017, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, R.H. The Determination of Cloud Masses and Dust Characteristics from Submillimetre Thermal Emission. Q. J. R. Astron. Soc. 1983, 24, 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Trewhella, M.; Davies, J.I.; Alton, P.B.; Bianchi, S.; Madore, B.M. ISO Long Wavelength Spectrograph Observations of Cold Dust in Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2000, 543, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | |

| 2. | Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia with an important NASA participation |

| Galaxy Name | RA (hh:mm:ss.s) | DEC (dd:mm:ss.s) | Morphology | Distance (Mpc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGC 2841 | 09:22:02.7 | +50:58:35.3 | SAa C | 14.6 |

| NGC 3077 | 10:03:19.1 | +68:44:02.2 | S0 C | 3.8 |

| NGC 3184 | 10:18:17.0 | +41:25:27.8 | SAc C | 11.3 |

| NGC 3351 | 10:43:57.7 | +11:42:13.0 | SBb C | 10.5 |

| Galaxy Name | Semi-Major Axis Arcsec | Semi-Minor Axis Arcsec | PA Degrees | Jy Arcsec | ×10M | ×10M | Dust-to-Gas Ratio % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGC 2841 | 140 | 70 | 150 | 24.4 | 6.6 | 9.0 | 0.7 |

| NGC 3077 | 30 | 22 | 65 | 36.1 | 0.7 | 0.04 | 17.5 |

| NGC 3184 | 140 | 100 | 117 | 34.5 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| NGC 3351 | 110 | 110 | 163 | 65.3 | 9.1 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Armijos-Abendaño, J.; López, E.; Llerena, M.; Aldás, F.; Logan, C. Dust Deficiency in the Interacting Galaxy NGC 3077. Galaxies 2017, 5, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies5030053

Armijos-Abendaño J, López E, Llerena M, Aldás F, Logan C. Dust Deficiency in the Interacting Galaxy NGC 3077. Galaxies. 2017; 5(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies5030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmijos-Abendaño, Jairo, Ericson López, Mario Llerena, Franklin Aldás, and Crispin Logan. 2017. "Dust Deficiency in the Interacting Galaxy NGC 3077" Galaxies 5, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies5030053

APA StyleArmijos-Abendaño, J., López, E., Llerena, M., Aldás, F., & Logan, C. (2017). Dust Deficiency in the Interacting Galaxy NGC 3077. Galaxies, 5(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies5030053