Dutch Health Council Advisory Report on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Taking the Wrong Turn

Abstract

1. Terms of Reference for the Dutch Health Council

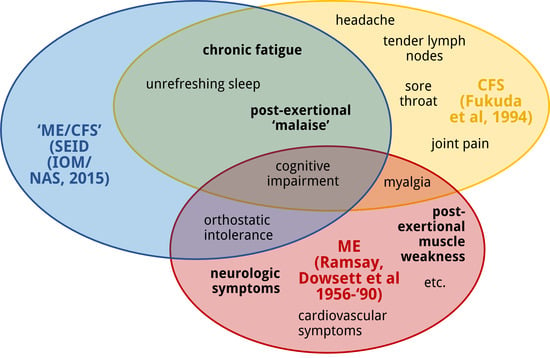

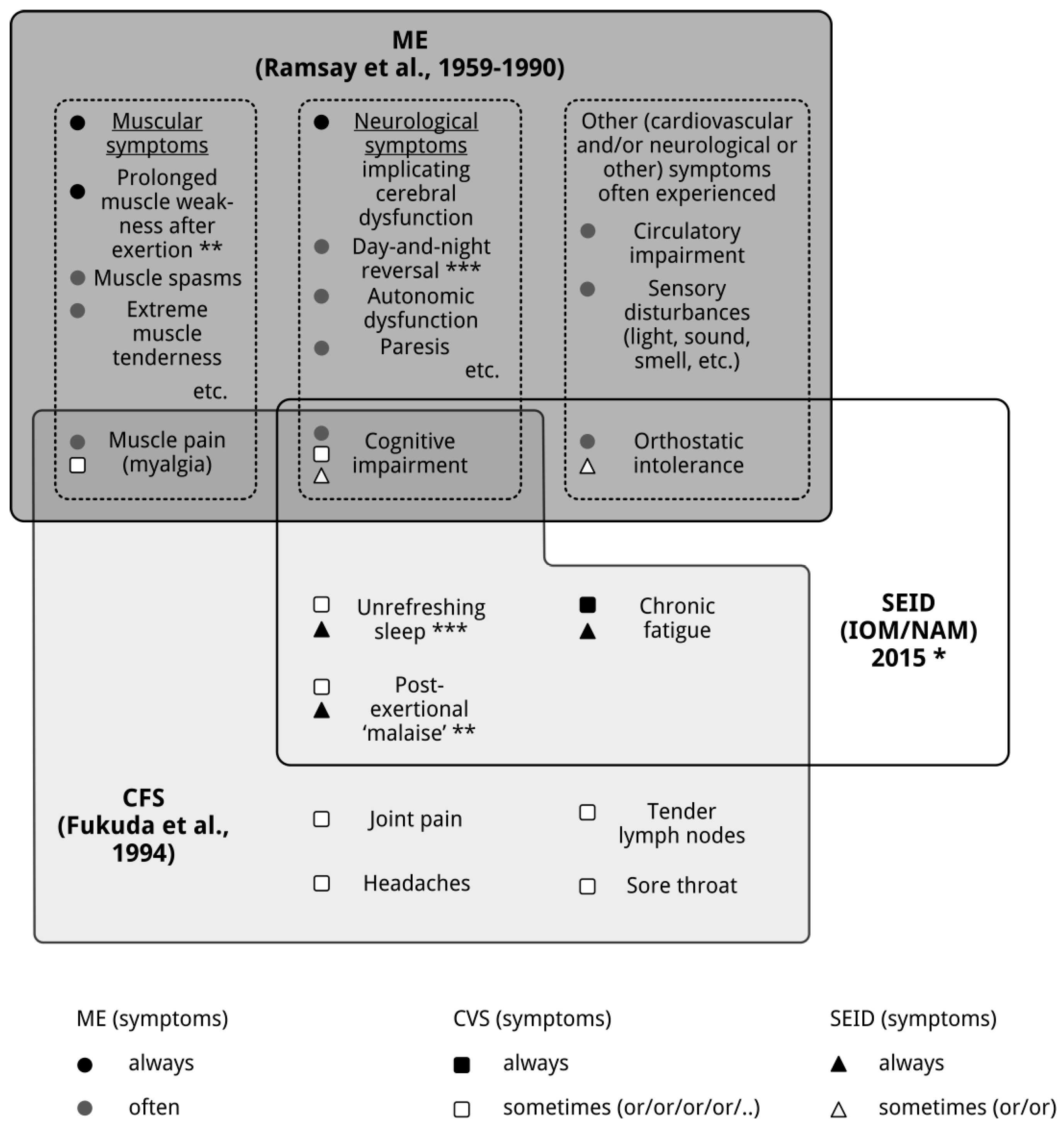

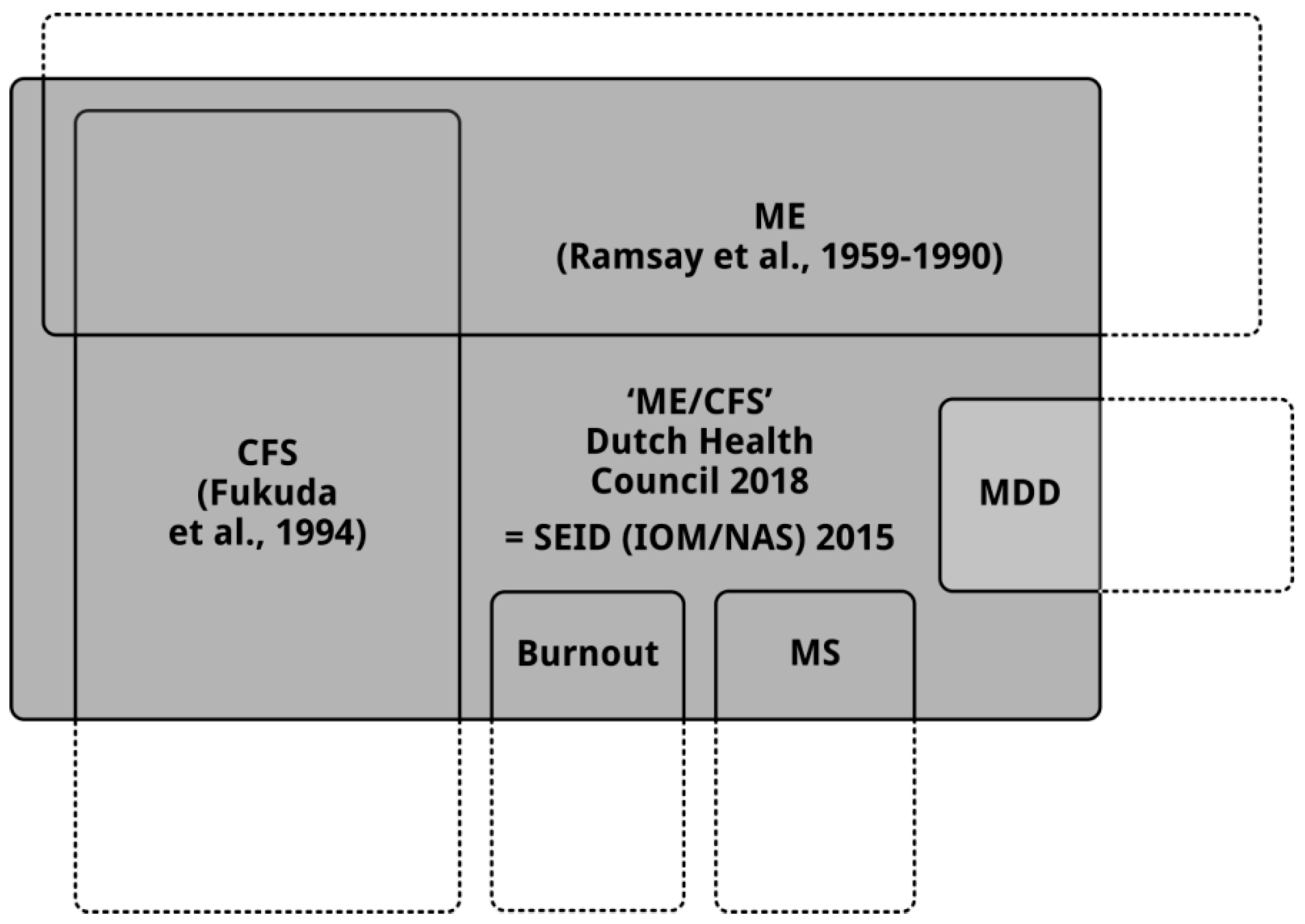

2. ME, CFS and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease (SEID): Three Distinct Clinical Entities

3. How the Dutch Health Council’s Advisory Report Came into Being

3.1. Assignment

3.2. Method

3.3. Outcome

4. Due to the New Definition of “ME/CFS” the Four Recommendations Will Have Negative Consequences for Patients with ME and Patients with CFS

4.1. The Consequences of the Wrong Definition for Research into ME

4.2. The Consequences of the Wrong Definition for the Scope of Academic Expertise Centers and Instalment of a Care Network for Patients with ME and Patients with CFS

4.3. The Consequences of a Wrong Definition of ME for the (Re)education of Medical Professionals and Care Takers

4.4. The Consequences of a Wrong Definition of ME (and CFS) and Not Using Objective Tests for the Rights to~Receive a Disability Income, Care and Medical Aid

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acheson, E.D. The clinical syndrome variously called benign myalgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neuromyasthenia. Am. J. Med. 1959, 26, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheson, D.E. A new clinical entity? Lancet 1956, 267, 789–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, A.M.; Dowsett, E.G. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: Then and now. In The Clinical and Scientific Basis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 1st ed.; Hyde, B.M., Goldstein, J., Levine, P., Eds.; The Nightingale Research Foundation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett, E.G.; Ramsay, A.M.; McCartney, R.A.; Bell, E.J. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis—A persistent enteroviral infection? Postgrad. Med. J. 1990, 66, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, K.; Straus, S.E.; Hickie, I.; Sharpe, M.; Dobbins, J.G.; Komaroff, A.L. The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, G.P.; Kaplan, J.E.; Gantz, N.M.; Komaroff, A.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Straus, S.E.; Jones, J.F.; Dubois, R.E.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Pahwa, S. Chronic fatigue syndrome: A working case definition. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988, 108, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowsett, E.G. Myalgic encephalomyelitis, or what? Lancet 1988, 332, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness; Institute of Medicine: Washington, WA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-309-31689-7. [Google Scholar]

- Twisk, F.N.M. Replacing Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome with systemic exercise intolerance disease is not the way forward. Diagnostics 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twisk, F.N.M. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease: Three distinct clinical entities. Challenges 2018, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Sunnquist, M.; Kot, B.; Brown, A. Unintended consequences of not specifying exclusionary illnesses for systemic exertion intolerance disease. Diagnostics 2015, 5, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal (Dutch Parliament). Adviesaanvraag van de Tweede Kamer aan de Gezondheidsraad (Request of Advice by the Dutch Health Council). Den Haag (The Hague). 2015. Available online: https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/sites/default/files/grpublication/adviesaanvraag_myalgische_encefalomyelitis.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2015).

- Haney, E.; Smith, M.E.; McDonagh, M.; Pappas, M.; Daeges, M.; Wasson, N.; Nelson, H.D. Diagnostic methods for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention workshop. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.E.B.; Nelson, H.D.; Haney, E.; Pappas, M.; Daeges, M.; Wasson, N.; McDonagh, M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 219; AHRQ Publication No. 15-E001-EF; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014; Addendum July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.E.; Haney, E.; McDonagh, M.; Pappas, M.; Daeges, M.; Wasson, N.; Fu, R.; Nelson, H.D. Treatment of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gezondheidsraad. ME/CVS. Den Haag. 2018. Available online: https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/sites/default/files/grpublication/kernadvies_me_cvs_1.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2018).

- Verschuren, C.M.; Nauta, A.P.; Bastiaanssen, M.H.H.; Terluin, B.; Vendrig, A.A.; Verbraak, M.J.P.M.; Flikweert, S.; Vriezen, J.A.; van Zanten-Przybysz, I.; Loo, M.A.J.M. Richtlijn één lijn in de Eerste lijn bij Overspanning en Burnout. Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Overspanning en Burnout voor Eerstelijns Professionals (Multidisciplinary Guideline for Being Overstrained and Burnout for Front-line Professionals). Amsterdam/Utrecht. 2011. Available online: https://www.nvab-online.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden-webpaginas/MDRL_Overspanning-Burnout.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2018).

- Parker, K.J.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Lyons, D.M. Neuroendocrine aspects of hypercortisolism in major depression. Horm. Behav. 2003, 43, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, C.; Newton, J.; Watson, S. A review of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in chronic fatigue syndrome. ISRN Neurosci. 2013, 2013, 784520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Eede, F.; Moorkens, G.; Hulstijn, W.; Van Houdenhove, B.; Cosyns, P.; Sabbe, B.G.; Claes, S.J. Combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing factor test in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mommersteeg, P.M.; Heijnen, C.J.; Verbraak, M.J.; van Doornen, L.J. Clinical burnout is not reflected in the cortisol awakening response, the day-curve or the response to a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Hickie, I.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Wakefield, D.; Parker, G.; Straus, S.E.; Dale, J.; McCluskey, D.; Hinds, G.; Brickman, A.; et al. What is chronic fatigue syndrome? Heterogeneity within an international multicentre study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2001, 35, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twisk, F.N.M. The status of and future research into Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: The need of accurate diagnosis, objective assessment, and acknowledging biological and clinical subgroups. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessely, S.; Nimnuan, C.; Sharpe, M. Functional somatic syndromes: One or many? Lancet 1999, 354, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.D.; Goldsmith, K.A.; Johnson, A.L.; Potts, L.; Walwyn, R.; DeCesare, J.C.; Baber, H.L.; Burgess, M.; Clark, L.V.; Cox, D.L.; et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): A randomised trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilshire, C.; Kindlon, T.; Matthees, A.; McGrath, S. Can patients with chronic fatigue syndrome really recover after graded exercise or cognitive behavioural therapy? A critical commentary and preliminary re-analysis of the PACE trial. Fatigue 2017, 5, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twisk, F.N.M. Graded exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome in GETSET. Lancet 2018, 391, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunnquist, M.; Nicholson, L.; Jason, L.A.; Friedman, K.J. Access to medical care for individuals with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: A call for centers of excellence. Mod. Clin. Med. Res. 2017, 1, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kimpe, A.; Crijnen, B.; Kuijper, J.; Verhulst, I.; van der Ploeg, Y. Zorg voor ME—Enquête onder ME-Patiënten naar Hun Ervaringen met de Zorg in Nederland 2016 (Care for ME—Survey of ME Patients about Their Experiences with Health Care in The Netherlands, 2016); ME/CVS vereniging: Driehuizen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deale, A.; Wessely, S. Patient’s perceptions of medical care in chronic fatigue syndrome. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, J.; Hirano, M.; Karaa, A.; Shepard, E.; Thompson, J.L.P. Diagnostic odyssey of patients with mitochondrial disease: Results of a survey. Neurol. Genet. 2018, 4, e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojcik, W.; Armstrong, D.; Kanaan, R. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Labels, meanings and consequences. J. Psychosom. Res. 2011, 70, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holgate, S.T.; Komaroff, A.L.; Mangan, D.; Wessely, S. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Understanding a complex illness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlaes, J.L.; Jason, L.A.; Ferrari, J.R. The development of the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Attitudes Test. A psychometric analysis. Eval. Health Prof. 1999, 22, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Taylor, R.R.; Plioplys, S.; Stepanek, Z.; Shlaes, J. Evaluating attributions for an illness based upon the name: Chronic fatigue syndrome, myalgic encephalopathy and Florence Nightingale disease. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looper, K.J.; Kirmayer, L.J. Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollebregt, B. Chronische Vermoeidheid Blijft Raadselachtig. 2018. Available online: https://www.trouw.nl/samenleving/chronische-vermoeidheid-blijft-raadselachtig~a516cbdc (accessed on 19 March 2018).

- RTL Nieuws. Erkenning voor ME-patiënt: Chronische Vermoeidheid Aangemerkt als Ernstige Ziekte. 2018. Available online: https://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nederland/erkenning-voor-me-patient-chronische-vermoeidheid-aangemerkt-als-ernstige-ziekte (accessed on 19 March 2018).

- Twisk, F.N.M. Accurate diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome based upon objective test methods for characteristic symptoms. World J. Methodol. 2015, 5, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twisk, F.N.M. Prolonged abnormal effects of exercise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Jacobs J. Physiother. Exerc. 2015, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, L.; Wood, L.; Behan, W.M.; Maclaren, W.M. Demonstration of delayed recovery from fatiguing exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur. J. Neurol. 1999, 6, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Smith, A. An investigation into the cognitive deficits associated with chronic fatigue syndrome. Open Neurol. J. 2009, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell, C.R.; Stevens, S.R.; Davenport, T.E.; Van Ness, J.M. Discriminative validity of metabolic and workload measurements to identify individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.B.; Light, A.R.; Light, K.C.; Broderick, G.; Shields, M.R.; Dougherty, R.J.; Meyer, J.D.; Van Riper, S.; Stegner, A.J.; Ellingson, L.D.; et al. Neural consequences of post-exertion malaise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 62, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, G.K.; Lewis, D.P.; Richardson, A.M.; Lidbury, B.A. Comorbidity of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome in an Australian cohort. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 275, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, I.; Pairman, J.; Spickett, G.; Newton, J.L. Clinical characteristics of a novel subgroup of chronic fatigue syndrome patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miwa, K.; Inoue, Y. The etiologic relation between disequilibrium and orthostatic intolerance in patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue syndrome). J. Cardiol. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingdon, C.C.; Bowman, E.W.; Curran, H.; Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E.M. Functional status and well-being in people with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome compared with people with Multiple Sclerosis and healthy controls. Pharmacoecon. Open 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Fagioli, L.R.; Doolittle, T.H.; Gandek, B.; Gleit, M.A.; Guerriero, R.T.; Kornish, R.J., 2nd; Ware, N.C.; Ware, J.E., Jr.; Bates, D.W. Health status in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and in general population and disease comparison groups. Am. J. Med. 1996, 101, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.S.; Resch, S.C.; Brimmer, D.J.; Johnson, A.; Kennedy, S.; Burstein, N.; Simon, C.J. The economic impact of chronic fatigue syndrome in Georgia: Direct and indirect costs. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2011, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Verzekeringsgeneeskunde (Dutch Association of Medical Insurance Physicians). Aanvulling op het Standpunt van de NVVG en GAV over het GR-advies ME/CVS: Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn CVS uit 2013 Blijft Onveranderd van Kracht en Prevaleert. 2018. Available online: https://www.nvvg.nl/nieuws/nieuws-nvvg/aanvulling-op-het-standpunt-van-de-nvvg-en-gav-over-het-gr-advies-mecvs/ (accessed on 30 March 2018).

- Carruthers, B.M.; van de Sande, M.I.; de Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International consensus criteria. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, B.M.; Jain, A.K.; de Meirleir, K.; Peterson, D.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Lerner, A.M.; Bested, A.C.; Flor-Henry, P.; Joshi, P.; Powles, A.C.P.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 2003, 11, 7–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Twisk, F. Dutch Health Council Advisory Report on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Taking the Wrong Turn. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics8020034

Twisk F. Dutch Health Council Advisory Report on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Taking the Wrong Turn. Diagnostics. 2018; 8(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics8020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleTwisk, Frank. 2018. "Dutch Health Council Advisory Report on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Taking the Wrong Turn" Diagnostics 8, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics8020034

APA StyleTwisk, F. (2018). Dutch Health Council Advisory Report on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Taking the Wrong Turn. Diagnostics, 8(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics8020034