Advancements in Hyaluronic Acid Effect in Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Ridge Alterations After Tooth Extraction

1.2. Factors Influencing Post-Extraction Dimensional Changes

1.3. Alveolar Ridge Preservation

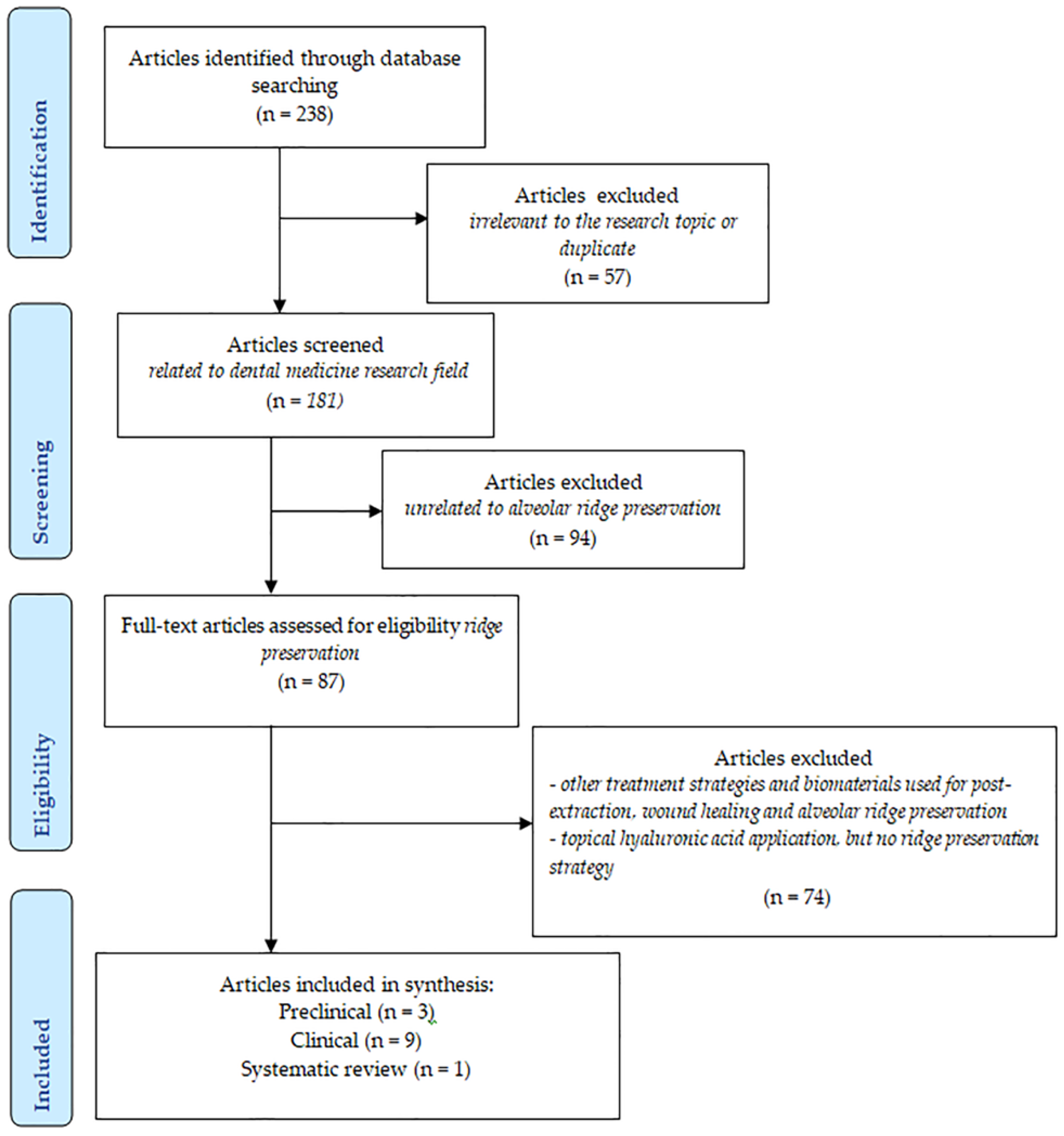

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Literature Search

2.2. Selection of the Studies

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Hyaluronic Acid Molecule and Functions

3.2. Common Applications of HYA in Dentistry

3.3. HYA Effects in Alveolar Ridge Preservation of Natural or Infected Sockets

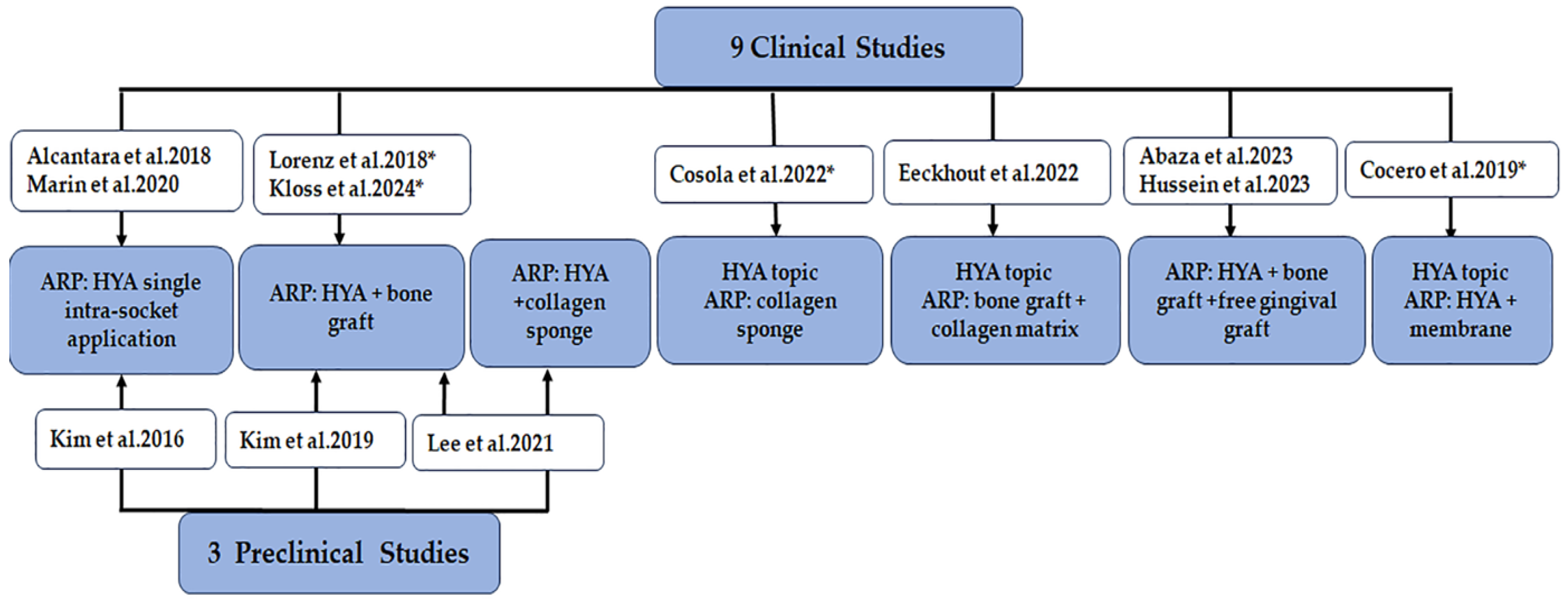

3.3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.3.2. Study Intervention and HYA Information

3.3.3. The Efficacy of HYA in Alveolar Ridge Preservation Procedures

Clinical Bone- and Soft Tissue-Related Outcomes from Clinical Studies

Imagistic Bone-Related Outcomes from Clinical Studies

Imagistic Bone-Related Outcomes from Preclinical Studies

Implant-Related Performance

Histomorphometric Data from Clinical Studies

Histomorphometric Data from Pre-Clinical Studies

3.3.4. Histological Data Associated with HYA Application in Post-Extraction Sockets

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araujo, M.G.; Lindhe, J. Dimensional ridge alterations following tooth extraction. An experimental study in the dog. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.L.; Wong, T.L.; Wong, M.C.; Lang, N.P. A systematic review of post-extractional alveolar hard and soft tissue dimensional changes in humans. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23 (Suppl. S5), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Ben Amara, H.; Chung, I.; Koo, K.T. Compromised extraction sockets: A new classification and prevalence involving both soft and hard tissue loss. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2021, 51, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Weijden, F.; Dell’Acqua, F.; Slot, D.E. Alveolar bone dimensional changes of post-extraction sockets in humans: A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Marzola, A.; Bozzi, L.; Liljenberg, B.; Lindhe, J. Modeling and remodeling of human extraction sockets. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.E.; Ioannidis, A.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Thoma, D.S. Alveolar ridge preservation in the esthetic zone. Periodontol. 2000 2018, 77, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schropp, L.; Wenzel, A.; Kostopoulos, L.; Karring, T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: A clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2003, 23, 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mardas, N.; Macbeth, N.; Donos, N.; Jung, R.E.; Zuercher, A.N. Is alveolar ridge preservation an overtreatment? Periodontol. 2000 2023, 93, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couso-Queiruga, E.; Stuhr, S.; Tattan, M.; Chambrone, L.; Avila-Ortiz, G. Post-extraction dimensional changes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, M.R.; Jin, L. Learn, unlearn, and relearn post-extraction alveolar socket healing: Evolving knowledge and practices. J. Dent. 2024, 145, 104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morjaria, K.R.; Wilson, R.; Palmer, R.M. Bone healing after tooth extraction with or without an intervention: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2014, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barootchi, S.; Wang, H.-L.; Ravida, A.; Ben Amor, F.; Riccitiello, F.; Rengo, C.; Paz, A.; Laino, L.; Marenzi, G.; Gasparro, R.; et al. Ridge preservation techniques to avoid invasive bone reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Implantol. 2019, 12, 399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Barootchi, S.; Tavelli, L.; Majzoub, J.; Stefanini, M.; Wang, H.L.; Avila-Ortiz, G. Alveolar ridge preservation: Complications and cost-effectiveness. Periodontol. 2000 2023, 92, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, A.; Mardas, N.; Mezzomo, L.A.; Needleman, I.G.; Donos, N. Alveolar ridge preservation. A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhekar, S.; Kernen, F.; Bidra, A.S. Clinical and histologic outcomes of socket grafting after flapless tooth extraction: A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 113, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Heggeler, J.M.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A. Effect of socket preservation therapies following tooth extraction in non-molar regions in humans: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implant Res. 2011, 22, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natto, Z.S.; Parashis, A.; Steffensen, B.; Ganguly, R.; Finkelman, M.D.; Jeong, Y.N. Efficacy of collagen matrix seal and collagen sponge on ridge preservation in combination with bone allograft: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulos, G.S.; Koidou, V.P.; Sonnenberger, M.; Johnson, D.; Chu, H.; Wolff, L.F. Postextraction ridge preservation by using dense PTFE membranes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, V.; Araujo, M.G.; Buser, D. Clinical relevance of dimensional bone and soft tissue alterations post-extraction in esthetic sites. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 73, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Jung, R.E.; Avila-Ortiz, G.; Blanco, J.; Cosyn, J.; Fickl, S.; Figuero, E.; Goldstein, M.; Graziani, F.; Madianos, P.; et al. Management of the extraction socket and timing of implant placement: Consensus report and clinical recommendations of group 3 of the XV European Workshop in Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsmill, V. Post-extraction remodeling of the adult mandible. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1999, 10, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Lee, C.; Yagita, H.; Williams, D.W.; Sung, E.C.; Hong, C.; Shin, K.-H.; Kang, M.K.; et al. Removal of pre-existing periodontal inflammatory condition before tooth extraction ameliorates medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw-like lesion in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 2318–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigarida, A.; Toscano, J.; Bezerra, B.d.B.; Geminiani, A.; Barmak, A.B.; Caton, J.; Papaspyridakos, P.; Chochlidakis, K. Buccal bone thickness of maxillary anterior teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 1326–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.G.; Hürzeler, M.B.; Dias, D.R.; Matarazzo, F. Minimal invasiveness in the alveolar ridge preservation, with or without concomitant implant placement. Periodontol. 2000 2023, 91, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Shen, D. Pathogenesis and treatment of wound healing in patients with diabetes after tooth extraction. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 949535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, L.; Devlin, H.; Ting, K.; Nishimura, I. Current perspectives in residual ridge remodeling and its clinical implications: A review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1998, 80, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, A.-M.; Taguchi, A.; Hujoel, P.P.; Hollender, L.G. Number of teeth and residual alveolar ridge height in subjects with a history of self-reported osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2004, 15, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Gupta, M. Oral conditions in renal disorders and treatment considerations–a review for pediatric dentist. Saudi Dent. J. 2015, 27, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, J.B.; Casati, M.Z.; Neto, F.H.; Sallum, E.A.; Nociti, F.H., Jr. Smoking may affect the alveolar process dimensions and radiographic bone density in maxillary extraction sites: A prospective study in humans. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, V.; Engel, O.; Reyes, M.; Shahim, K.; Nolte, L.P.; Buser, D. Ridge alterations post-extraction in the esthetic zone: A 3D analysis with CBCT. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92 (Suppl. S12), 195S–201S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, I.; Chen, S.T.; Buser, D. Ridge preservation techniques for implant therapy. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2009, 24, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mardas, N.; Trullenque-Eriksson, A.; MacBeth, N.; Petrie, A.; Donos, N. Does ridge preservation following tooth extraction improve implant treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26 (Suppl. S11), 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacBeth, N.; Trullenque-Eriksson, A.; Donos, N.; Mardas, N. Hard and soft tissue changes following alveolar ridge preservation: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2017, 28, 982–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Ortiz, G.; Chambrone, L.; Vignoletti, F. Effect of alveolar ridge preservation interventions following tooth extraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, P.; Manicone, P.F.; Liguori, M.G.; D’Addona, A.; Ciolfi, A.; Cavalcanti, C.; Piccirillo, D.; Rella, E. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of implant-supported single-unit crowns with cantilever extensions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 33, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atieh, M.A.; Shah, M.; Hakam, A.; AlAli, F.; Aboushakra, I.; Alsabeeha, N.H.M. Alveolar ridge preservation versus early implant placement in single non-molar sites: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yafi, F.; Alchawaf, B.; Nelson, K. What Is the Optimum for Alveolar Ridge Preservation? Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, A.; Alotaibi, A.A.; Aljaeidi, Y.; Alqhtani, N.R. The Need for Socket Preservation: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Zhurakivska, K.; Lo Muzio, L.; Laino, L.; Cicciù, M.; Lo Russo, L. Combination of Bone Graft and Resorbable Membrane for Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisiguiña Salem, C.; Ruiz Delgado, E.; Crespo Reinoso, P.A.; Robalino, J.J. Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Review of Concepts and Controversies. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 14, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-López Del Amo, F.; Monje, A. Efficacy of Biologics for Alveolar Ridge Preservation/Reconstruction and Implant Site Development: An American Academy of Periodontology Best Evidence Systematic Review. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1827–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Ortiz, G.; Bartold, P.; Giannobile, W.; Katagiri, W.; Nares, S.; Rios, H.; Spagnoli, D.; Wikesjö, U. Biologics and Cell Therapy Tissue Engineering Approaches for the Management of the Edentulous Maxilla: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2016, 31, S121–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, D.S.; Bienz, S.P.; Lim, H.C.; Lee, W.Z.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Jung, R.E. Explorative Randomized Controlled Study Comparing Soft Tissue Thickness, Contour Changes, and Soft Tissue Handling of Two Ridge Preservation Techniques and Spontaneous Healing Two Months After Tooth Extraction. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2020, 31, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalmair, T.; Fickl, S.; Schneider, D.; Hinze, M.; Wachtel, H. Dimensional Alterations of Extraction Sites After Different Alveolar Ridge Preservation Techniques—A Volumetric Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canullo, L.; Del Fabbro, M.; Khijmatgar, S.; Panda, S.; Ravidà, A.; Tommasato, G.; Sculean, A.; Pesce, P. Dimensional and Histomorphometric Evaluation of Biomaterials Used for Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.R.; Chen, C.Y.; Kim, D.M.; Machtei, E.E. Ridge Preservation Procedures Revisited: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate Dimensional Changes with Two Different Surgical Protocols. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Ortiz, G.; Gubler, M.; Romero-Bustillos, M.; Nicholas, C.; Zimmerman, M.; Barwacz, C. Efficacy of Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domic, D.; Bertl, K.; Lang, T.; Pandis, N.; Ulm, C.; Stavropoulos, A. Hyaluronic Acid in Tooth Extraction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preclinical and Clinical Trials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 7209–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Song, H.Y.; Ben Amara, H.; Kyung-Rim, K.; Koo, K. Hyaluronic Acid Improves Bone Formation in Extraction Sockets with Chronic Pathology: A Pilot Study in Dogs. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.W.; LaChaud, G.; Shen, J.; Asatrian, G.; Nguyen, V.; Zhang, X.; Ting, K.; Soo, C. A Review of the Clinical Side Effects of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2016, 22, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embery, G.; Oliver, W.M.; Stanbury, J.B.; Purvis, J.A. The Electrophoretic Detection of Acidic Glycosaminoglycans in Human Gingival Sulcus Fluid. Arch. Oral Biol. 1982, 27, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embery, G.; Waddington, R.J.; Hall, R.C.; Last, K.S. Connective Tissue Elements as Diagnostic Aids in Periodontology. Periodontol. 2000 2000, 24, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogrel, M.A.; Lowe, M.A.; Stern, R. Hyaluronan (Hyaluronic Acid) in Human Saliva. Arch. Oral Biol. 1996, 41, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.R.; Laurent, T.C.; Laurent, U.B. Hyaluronan: Its Nature, Distribution, Functions, and Turnover. J. Intern. Med. 1997, 242, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertl, K.; Bruckmann, C.; Isberg, P.E.; Klinge, B.; Gotfredsen, K.; Stavropoulos, A. Hyaluronan in Non-Surgical and Surgical Periodontal Therapy: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, A.; Vishnani, R.; Reche, A.; Buldeo, J.; Wadher, B. Hyaluronic Acid: Exploring Its Versatile Applications in Dentistry. Cureus 2023, 15, e46349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabe, C.; Adel-Khattab, D.; Kluk, E.; Struck, R.; Stiller, M. Effect of a Particulate and a Putty-Like Tricalcium Phosphate-Based Bone-Grafting Material on Bone Formation, Volume Stability and Osteogenic Marker Expression After Bilateral Sinus Floor Augmentation in Humans. J. Funct. Biomater. 2017, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, M.; Humeniuk, E.; Adamczuk, G.; Korga-Plewko, A. Hyaluronic Acid as a Modern Approach in Anticancer Therapy: Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokeshwar, V.B.; Iida, N.; Bourguignon, L.Y. The Cell Adhesion Molecule, GP116, Is a New CD44 Variant (Ex14/v10) Involved in Hyaluronic Acid Binding and Endothelial Cell Proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 23853–23864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesley, J.; Kincade, P.W.; Hyman, R. Antibody-Induced Activation of the Hyaluronan Receptor Function of CD44 Requires Multivalent Binding by Antibody. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993, 23, 1902–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Bezerra, B.; Mendes Brazão, M.A.; de Campos, M.L.; Casati, M.Z.; Sallum, E.A.; Sallum, A.W. Association of Hyaluronic Acid with a Collagen Scaffold May Improve Bone Healing in Critical-Size Bone Defects. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, P.; Peng, X.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, X. The Application of Hyaluronic Acid in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Choe, J.; Hahn, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Jeon, J.; Choi, C.; Kim, Y.-M.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid Promotes Angiogenesis by Inducing RHAMM-TGFbeta Receptor Interaction via CD44-PKCdelta. Mol. Cells 2012, 33, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, M.A.; Cassano, A.; Vincenti, A.; Vinella, A.; Dell’olio, F.; Favia, G.; Mariggiò, M.A. In Vitro Evaluation of the Effects of Hyaluronic Acid and an Aminoacidic Pool on Human Osteoblasts. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyoshi, W.; Okinaga, T.; Knudson, C.B.; Knudson, W.; Nishihara, T. High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid Regulates Osteoclast Formation by Inhibiting Receptor Activator of NF-κB Ligand Through Rho Kinase. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloss, F.R.; Kau, T.; Heimes, D.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Kloss-Brandstätter, A. Enhanced Alveolar Ridge Preservation with Hyaluronic Acid-Enriched Allografts: A Comparative Study of Granular Allografts with and Without Hyaluronic Acid Addition. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2024, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnazar, P.; Wolinsky, L.; Nachnani, S.; Haake, S.; Pilloni, A.; Bernard, G.W. Bacteriostatic Effects of Hyaluronic Acid. J. Periodontol. 1999, 70, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, P.; Kamal, R. Hyaluronic Acid: A Boon in Periodontal Therapy. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.V.; Acharya, A.B.; Bhadbhade, S.; Thakur, S.L. Hyaluronan-Containing Mouthwash as an Adjunctive Plaque-Control Agent. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2010, 8, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Eick, S.; Renatus, A.; Heinicke, M.; Pfister, W.; Stratul, S.I.; Jentsch, H. Hyaluronic Acid as an Adjunct After Scaling and Root Planing: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hofling, K.; Fimmers, R.; Frentzen, M.; Jervoe-Storm, P.M. Clinical and Microbiological Effects of Topical Subgingival Application of Hyaluronic Acid Gel Adjunctive to Scaling and Root Planing in the Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2004, 75, 1114–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistorius, A.; Martin, M.; Willershausen, B.; Rockmann, P. The Clinical Application of Hyaluronic Acid in Gingivitis Therapy. Quintessence Int. 2005, 36, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sapna, N.; Vandana, K.L. Evaluation of Hyaluronan Gel (Gengigel) as a Topical Applicant in the Treatment of Gingivitis. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2011, 2, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakata, Y.; Imafuji, T.; Nakamura, T.; Kawakami, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Pilloni, A.; Sculean, A. Periodontal Wound Healing/Regeneration of Two-Wall Intrabony Defects Following Reconstructive Surgery with Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid-Gel with or Without a Collagen Matrix: A Preclinical Study in Dogs. Quintessence Int. 2021, 52, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakata, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Kawakami, Y.; Imafuji, T.; Shinohara, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Sculean, A. Healing of Buccal Gingival Recessions Following Treatment with Coronally Advanced Flap Alone or Combined with a Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid Gel. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcântara, C.E.P.; Castro, M.A.A.; de Noronha, M.S.; Martins-Junior, P.A.; Mendes, R.d.M.; Caliari, M.V.; Mesquita, R.A.; Ferreira, A.J. Hyaluronic Acid Accelerates Bone Repair in Human Dental Sockets: A Randomized Triple-Blind Clinical Trial. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, J.; Barbeck, M.; Kirkpatrick, C.J.; Sader, R.; Lerner, H.; Ghanaati, S. Injectable Bone Substitute Material on the Basis of Beta-TCP and Hyaluronan Achieves Complete Bone Regeneration While Undergoing Nearly Complete Degradation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2018, 33, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocero, N.; Ruggiero, T.; Pezzana, A.; Bezzi, M.; Carossa, S. Efficacy of Sodium Hyaluronate and Synthetic Amino Acids in Post-Extractive Sockets in Patients with Liver Failure: Split-Mouth Study. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, S.; Popovic-Pejicic, S.; Radosevic-Caric, B.; Trtic, N.; Tatic, Z.; Selakovic, S. Hyaluronic Acid Treatment Outcome on the Post-Extraction Wound Healing in Patients with Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Split-Mouth Study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2020, 25, e154–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeckhout, C.; Ackerman, J.; Gilbert, M.; Cosyn, J. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating Hyaluronic Acid Gel as a Wound Healing Agent in Alveolar Ridge Preservation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosola, S.; Oldoini, G.; Boccuzzi, M.; Giammarinaro, E.; Genovesi, A.; Covani, U.; Marconcini, S. Amino Acid-Enriched Formula for the Post-Operative Care of Extraction Sockets Evaluated by 3-D Intraoral Scanning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husseini, B.; Friedmann, A.; Wak, R.; Ghosn, N.; Khoury, G.; El Ghoul, T.; Abboud, C.K.; Younes, R. Clinical and Radiographic Assessment of Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid Addition in Demineralized Bovine Bone-Based Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Human Randomized Split-Mouth Pilot Study. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 124, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaza, G.; Abdel Gaber, H.K.; Afifi, N.S.; Adel-Khattab, D. Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin Versus Hyaluronic Acid with Bovine Derived Xenograft for Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial with Histomorphometric Analysis. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2024, 26, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Ben Amara, H.; Park, J.-c.; Kim, S.; Kim, T.-I.; Seol, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Ku, Y.; Rhyu, I.-C.; Koo, K.-T. Biomodification of Compromised Extraction Sockets Using Hyaluronic Acid and rhBMP-2: An Experimental Study in Dogs. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chu, S.; Ben Amara, H.; Song, H.; Son, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Koo, K.; Rhyu, I. The Effects of Hyaluronic Acid and Deproteinized Bovine Bone Mineral with 10% Collagen for Ridge Preservation in Compromised Extraction Sockets. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misch, C.E.; Perel, M.L.; Wang, H.-L.; Sammartino, G.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Trisi, P.; Steigmann, M.; Rebaudi, A.; Palti, A.; Pikos, M.A.; et al. Implant Success, Survival, and Failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus Conference. Implant Dent. 2008, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Acharya, A.B.; Alliot, C.; Eid, N.; Badran, Z.; Kareem, Y.; Rahman, B. Hyaluronic Acid in Dentoalveolar Regeneration: Biological Rationale and Clinical Applications. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2024, 14, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Canellas, J.V.; Medeiros PJ, D.A.; da Silva Figueredo, C.M.; Fischer, R.G.; Ritto, F.G. Which Is the Best Choice After Tooth Extraction: Immediate Implant Placement or Delayed Placement with Alveolar Ridge Preservation? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.A.; AlGhamdi, L.; AlKadi, M.; AlBeajan, N.; AlRashoudi, L.; AlHussan, M. The Burden of Diabetes, Its Oral Complications, and Their Prevention and Management. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, D.S.; Buranawat, B.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Held, U.; Jung, R.E. Efficacy of Soft Tissue Augmentation Around Dental Implants and in Partially Edentulous Areas: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, S77–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementini, M.; Castelluzzo, W.; Ciaravino, V.; Agostinelli, A.; Vignoletti, F.; De Sanctis, M. Impact of Treatment Modality After Tooth Extraction on Soft Tissue Dimensional Changes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2020, 31, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study and Design | Ridge Preservation Method Treatment Groups HYA Application form Commercial Product | Investigation Type Outcome Parameters Follow-Up Moments | Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcantara et al. 2018 [76] RCT, split-mouth, Humans |

| Radiographic assessment (CBCT scan) of alveolar dimensional changes, percentage of newly formed bone and fractal dimension Day 30, 90 | Test group | Control group | |||

| Newly formed bone (%), 30 d | 57.27 | 45.98 | p = 0.004 | ||||

| Newly formed bone (%), 90 d | 85.83 | 83.25 | p = 0.216 | ||||

| Buccolingual alveolar ridge width at the cervical/middle/apical thirds (mm), 90 d | 0.71/0.25/0.19 | 0.75/0.54/0.21 | p > 0.005 | ||||

| Fractal dimension, 30 d | 1.098 ± 0.042 | 1.074 ± 0.045 | p = 0.003 | ||||

| Fractal dimension, 90 d | No significant | differences | p > 0.005 | ||||

| Lorenz et al. 2018 [77] Clinical trial, Humans |

| Clinical assessment of implant survival/success Radiographic assessment of implant marginal bone loss Histology/morphometry 4 months for ARP 1 year for implant success | Implant survival rate, 1 y | 100% | |||

| Marginal bone loss (mm), 1 y | 0.136 | ||||||

| Amount of newly formed bone tissue (%), 4 m | 44.92 ± 5.16 | ||||||

| Amount of connective tissue (%), 4 m | 52.49 ± 6.43 | ||||||

| Amount of residual graft biomaterial (%), 4 m | 2.59 ± 2.05 | ||||||

| Cocero et al. 2019 [78] RCT, split-mouth Humans |

Patients with liver failure | Clinical assessment of the reduction of alveolar dimensions Day 7, 14, 21 | Test group | Control group | |||

| Oral-buccal diameters (mm), 7 d | 3.89 ± 1.73 | 4.64 ± 2.03 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Oral-buccal diameters (mm), 14 d | 2.09 ± 1.31 | 3.07 ± 1.51 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Oral-buccal diameters (mm), 21 d | 0.58 ± 1.11 | 1.21 ± 1.25 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mesio-distal diameters (mm), 7 d | 3.61 ± 1.84 | 4.69 ± 2.04 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mesio-distal diameters (mm), 14 d | 1.74 ± 1.54 | 2.82 ± 1.7 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mesio-distal diameters (mm), 21 d | 0.44 ± 1.02 | 1.16 ± 1.25 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Marin et al. 2020 [79] RCT, split-mouth Humans |

Patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes | Clinical assessment of wound closure rate and wound healing scale Day 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 | Test group | Control group | |||

| Wound closure rate (%), 5 d | 51.35 ± 18.35 | 29.11 ± 15.94 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Wound closure rate (%), 15 d | 74.86 ± 11.31 | 61.61 ± 15.78 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Wound closure rate (%), 25 d | 84.36 ± 7.76 | 74.53 ± 12.94 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Wound healing scale (%), 5 d (excellent) | 16.67 | 3.33 | p = 0.069 | ||||

| Wound healing scale (%), 15 d (excellent) | 53.33 | 20 | p = 0.021 | ||||

| Wound healing scale (%), 25 d (excellent) | 76.67 | 63.33 | p = 0.521 | ||||

| Eeckhout et al. 2022 [80] RCT Humans |

| Clinical assessment of wound healing (examination and intra-oral scan) Radiographic assessment (CBCT scan) of bone dimensions 1 week 3 weeks 4 months | Test group | Control group | |||

| Bucco-lingual wound reduction (mm), 1 w | 4.26 | 3.63 | p > 0.005 | ||||

| Bucco-lingual wound reduction (mm), 3 w | 0.77 | 1.03 | p = 0.259 | ||||

| Mesio-distal wound reduction (mm), 1 w | 2.00 | 2.2 | p > 0.005 | ||||

| Mesio-distal wound reduction (mm), 3 w | 0.57 | 0.49 | p = 0.259 | ||||

| Ridge width, 1 mm coronal, (mm), 4 m | 3.57 | 6.74 | p = 0.025 | ||||

| Ridge width, 3 mm coronal, (mm), 4 m | 6.37 | 8.36 | p = 0.016 | ||||

| Ridge width, 5 mm coronal, (mm), 4 m | 8.13 | 9.01 | p = 0.213 | ||||

| Horizontal bone shrinkage, (mm), 4 m | 3.55 | 1.92 | p = 0.025 | ||||

| Buccal bone height shrinkage (mm), 4 m | 1 | 0.45 | p = 0.237 | ||||

| Oral bone height shrinkage (mm), 4 m | 1.46 | 0.96 | p = 0.351 | ||||

| Buccal soft tissue height (mm), 4 m | 1.99 | 2.71 | p = 0.226 | ||||

| Oral soft tissue height (mm), 4 m | 2.38 | 1.62 | p = 0.303 | ||||

| Soft tissue profile changes (mm), 4 m | −1.13 | −1.06 | p = 0.660 | ||||

| Buccal soft tissue height changes, 4 m | 0.15 | 0.56 | p = 0.226 | ||||

| Oral soft tissue height changes (mm), 4 m | 0.28 | −0.14 | p = 0.303 | ||||

| Socket wound healing score, 1 w | 1.87 | 1.96 | p = 0.737 | ||||

| Socket wound healing score, 3 w | 1.3 | 1.09 | p = 0.424 | ||||

| Cosola et al. 2022 [81] RCT, Humans |

| Clinical assessment of swelling and soft tissue healing rate through 3D intra-oral scanner Day 7, 14 1 month 2 months | Test group | Control group | |||

| Volume change of the soft tissue (%). 7 d | 105.05 ± 5.74 | 109.15 ± 6.3 | p = 0.038 | ||||

| Volume change of the soft tissue (%), 2 m | 95.85 ± 1.81 | 95.55 ± 1.88 | p = 0.838 | ||||

| Husseini et al. 2023 [82] RCT, Humans |

| Radiographic assessment (CBCT scan) of volumetric and linear bone resorption Histologic assessment of the newly formed bone and residual graft biomaterial 4 months | Test group | Control group | |||

| Volumetric bone resorption value (%), 4 m | 26.96 ± 1.83 | 36.56 ± 1.69 | p = 0.018 | ||||

| Linear bone resorption value (mm) (%), 4 m | 0.73 ± 0.052 | 1.42 ± 0.16 | p = 0.018 | ||||

| Abaza et al. 2023 [83] RCT, Humans |

| Radiographic assessment (CBCT scan) of bone width and crestal bone height Clinical assessment of horizontal bone width and soft tissue thickness Histologic and morphometric assessment of the newly formed bone and residual graft biomaterial 4 months, 1 year | Test group 1 | Test group 2 | Control group | ||

| Radiographic bone width (mm), 4 m | 8.60 ± 1.27 | 9.78 ± 0.87 | 7.99 ± 0.89 | p = 0.007 | |||

| Radiographic crestal bone loss (mm), 4 m | −0.53 ± 0.11 | −0.33 ± 0.15 | −0.98 ± 0.18 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Clinical bone width (mm), 4 m | 6.38 ± 1.16 | 6.94 ± 1.18 | 6.00 ± 1.81 | p = 0.42 | |||

| Clinical bone width (mm), 1 y | 6.27 ± 0.36 | 6.88 ± 1 | 6.00 ± 0.9 | p = 0.700 | |||

| Difference of clinical bone width (mm), 1 y | −1.29 ± 0.58 | −0.56 ± 0.46 | −0.44 ± 1.35 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Clinical soft tissue thickness (mm), 4 m | 1.62 ± 0.44 | 1.50 ± 0.46 | 1.75 ± 0.38 | p = 0.516 | |||

| Clinical soft tissue thickness (mm), 1 y | 1.59 ± 0.33 | 1.47 ± 0.50 | 1.66 ± 0.31 | p = 0.621 | |||

| Difference soft tissue thickness (mm), 1 y | 0.21 ± 0.12 | −0.15 ± 0.08 | −0.9 ± 0.00 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Mean area fraction newly formed bone (%), 4 m | 28.74 ± 5.15 | 56.6 ± 7.35 | 24.05 ± 3.64 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Mean area fraction of mature bone (%), 4 m | 7.51 ± 3.63 | 18.26 ± 4.44 | 2.41 ± 1.36 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Mean area fraction of residual graft (%), 4 m | 6.76 ± 2.59 | 2.63 ± 1.27 | 2.71 ± 1.24 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Kloss et al. 2024 [66] Clinical trial Humans |

| Radiographic assessment (CBCT scan) of vertical and horizontal bone loss, graft stability, graft shrinkage rate and bone density Clinical and radiographic assessment of implant survival/success 4 months for alveolar ridge preservation 1 year for implant survival and success | Test group | Control group | |||

| Bone height loss (mm), 4 m | −0.19 ± 0.51 | −0.82 ± 0.95 | p = 0.011 | ||||

| Graft shrinkage rate (%), 4 m | 10.3 ± 7.7 | 16.9 ± 11.5 | p = 0.038 | ||||

| Bone density (HU), 4 m | 211.03 ± 67.35 | 132.66 ± 48.85 | p = 0.004 | ||||

| Implant quality scale (success), 1 y | 21 implants out of 21 | 18 implants out of 19 | p = 0.475 | ||||

| Radiographic periimplant bone loss < 2 mm, 1 y | 13 implants out of 21 | 10 implants out of 19 | p = 0.523 | ||||

| Study and Design | Ridge Preservation Method Treatment Groups HYA Application form and Commercial Product Information | Investigation Type Outcome Parameters Follow-Up Moments | Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim JJ et al. 2016 [49] Preclinical study Dogs |

| Clinical assessment of wound healing. Histological/morphometric assessment 3 months | Test group | Control group | ||||

| Mineralized bone (%), 3 m | 63.29 ± 9.78 | 47.80 ± 6.60 | p < 0.05 | |||||

| Bone marrow (%), 3 m | 34.73 ± 8.97 | 50.4 ± 6.38 | p < 0.057 | |||||

| Kim JJ et al. 2019 [84] Preclinical study Dogs |

| Radiographic (Micro-CT)/morphometric assessment Histomorphometry Immunohistochemical assessment of bone formation 3 months | Test group 1 | Test group 2 | Test group 3 | Control group | ||

| Net Area (%), 3 m | −6.55 ± 9.82 | 11.73 ± 4.73 | 15.94 ± 3.12 | −10.74 ± 1.78 | p < 0.05 | |||

| Bone volume density (%), 3 m | 17.89 ± 6.02 | 20.06 ± 6.27 | 20.11 ± 6.64 | 18.00 ± 6.62 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Immune positive cells for osteocalcin (n), 3 m | 83.00 ± 27.56 | 319.00 ± 138.63 | 281.67 ± 125.74 | 88.67 ± 43.00 | p < 0.05 | |||

| Lee JB et al. 2021 [85] Preclinical study Rats |

| Histologic assesement of mineralized bone formation Morphometric assessment of mineralized bone, newly formed bone, connective tissue, residual graft particles. Radiographic (Micro-CT)/morphometric assessment 1 months 2 months | Test group 1 | Test group 2 | Test group 3 | Test group 4 | ||

| Mineralized bone (%), 1 m | 34.61 ± 13.0 | 62.97 ± 4.39 | 43.58 ± 6.65 | 46.10 ± 9.73 | p = 0.024 | |||

| Mineralized bone (%), 3 m | 45.19 ± 3.06 | 64.69 ± 3.98 | 41.89 ± 5.03 | 59.94 ± 5.44 | p = 0.002 | |||

| Newly bone form (%), 1 m | 7.14 ± 1.84 | 17.73 ± 10.36 | 5.93 ± 2.46 | 16.82 ± 6.84 | p = 0.033 | |||

| Newly bone form (%), 3 m | 7.53 ± 2.19 | 15.53 ± 2.41 | 5.57 ± 1.44 | 11.30 ± 3.06 | p = 0.008 | |||

| Connective tissue (%), 1 m | 61.15 ± 24.36 | 33.18 ± 27.00 | 44.34 ± 9.22 | 33.08 ± 13.98 | p = 0.145 | |||

| Connective tissue (%), 3 m | 17.07 ± 6.79 | 10.82 ± 4.96 | 35.05 ± 10.49 | 12.26 ± 5.55 | p = 0.002 | |||

| Residual graft particles (%), 1 m | - | - | 2.75 ± 1.35 | 1.78 ± 0.78 | p = 0.225 | |||

| Residual graft particles (%), 3 m | - | - | 3.71 ± 1.39 | 2.96 ± 2.03 | p = 0.456 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nistor, P.A.; Cândea, A.; Micu, I.C.; Soancă, A.; Caloian, C.S.; Bârdea, A.; Roman, A. Advancements in Hyaluronic Acid Effect in Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15020137

Nistor PA, Cândea A, Micu IC, Soancă A, Caloian CS, Bârdea A, Roman A. Advancements in Hyaluronic Acid Effect in Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(2):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15020137

Chicago/Turabian StyleNistor, Paul Andrei, Andreea Cândea, Iulia Cristina Micu, Andrada Soancă, Carmen Silvia Caloian, Alina Bârdea, and Alexandra Roman. 2025. "Advancements in Hyaluronic Acid Effect in Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Narrative Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 2: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15020137

APA StyleNistor, P. A., Cândea, A., Micu, I. C., Soancă, A., Caloian, C. S., Bârdea, A., & Roman, A. (2025). Advancements in Hyaluronic Acid Effect in Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics, 15(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15020137