Predictive Factors of Significant Findings on Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Suspected Small Bowel Bleeding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Definitions

2.3. Patients

2.4. Capsule Endoscopy Procedures

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. SBCE Findings

3.2. Post CE Follow-Up

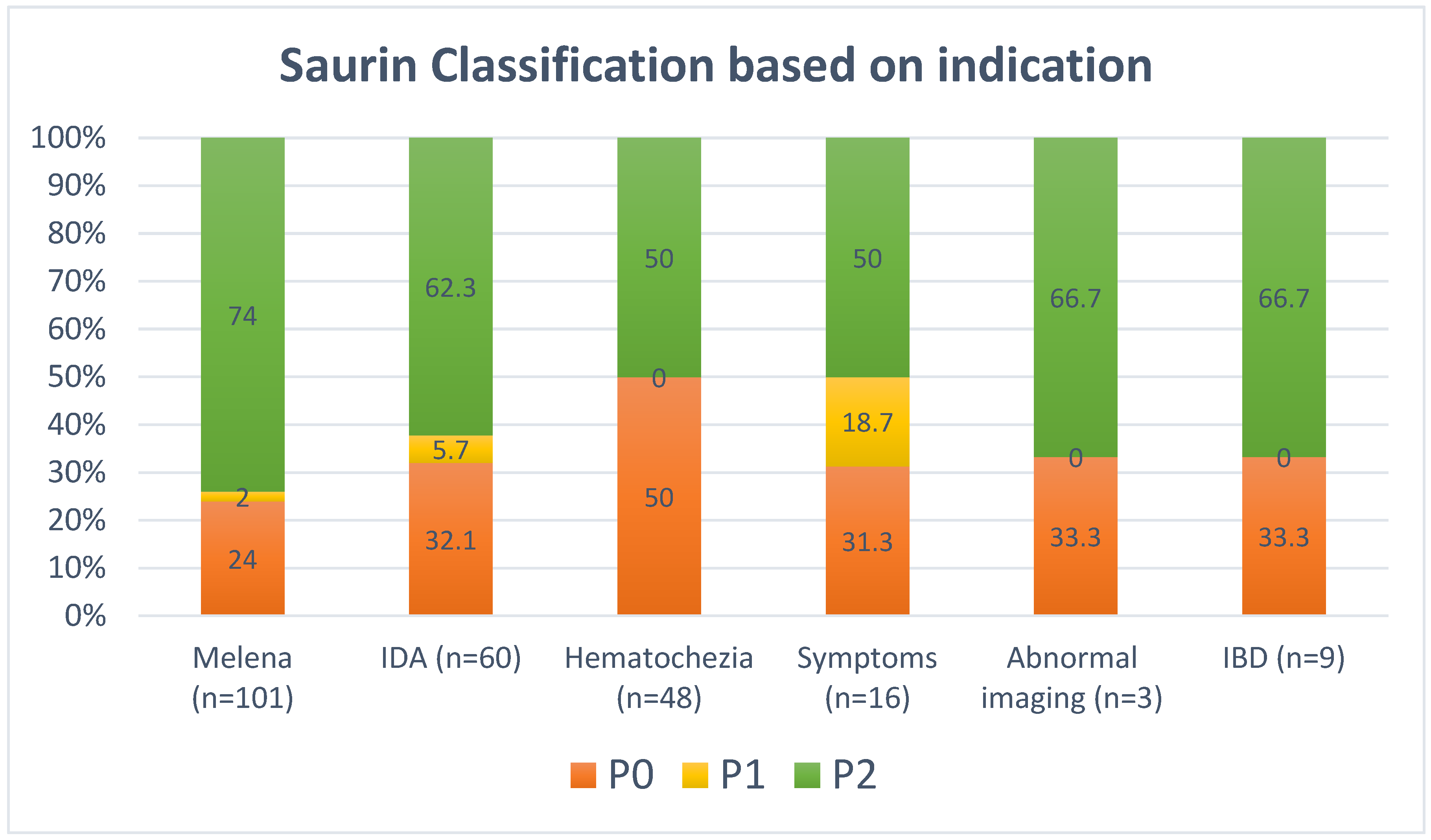

3.3. Saurin Classification and Predictors of Abnormal Findings

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| ESGE | European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| IDA | Iron deficiency anemia |

| SBCE | Small bowel capsule endoscopy |

| OGIB | Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding |

References

- Gunjan, D.; Sharma, V.; Rana, S.S.; Bhasin, D.K. Small bowel bleeding: A comprehensive review. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2014, 2, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, A.B.; Drozdowski, L.; Iordache, C.; Thomson, B.K.; Vermeire, S.; Clandinin, M.T.; Wild, G. Small bowel review: Diseases of the small intestine. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003, 48, 1582–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerson, L.B.; Fidler, J.L.; Cave, D.R.; Leighton, J.A. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1265–1287, quiz 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerson, L.; Kamal, A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of management strategies for obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008, 68, 920–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, P.; Ray, M.; Sidhu, R. Small bowel bleeding: Clinical diagnosis and management in the elderly. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 17, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singeap, A.-M.; Sfarti, C.; Minea, H.; Chiriac, S.; Cuciureanu, T.; Nastasa, R.; Stanciu, C.; Trifan, A. Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy and Enteroscopy: A Shoulder-to-Shoulder Race. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoobi, M.; Tan, J.; Alshammari, Y.; Scandrett, K.; Mofrad, K.; Takwoingi, Y. Video capsule endoscopy versus computed tomography enterography in assessing suspected small bowel bleeding: A systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 35, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshima, C.W.; Kuipers, E.J.; van Zanten, S.V.; Mensink, P.B. Double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: An updated meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 26, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennazio, M.; Rondonotti, E.; Despott, E.J.; Dray, X.; Keuchel, M.; Moreels, T.; Sanders, D.S.; Spada, C.; Carretero, C.; Cortegoso Valdivia, P.; et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2022. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 58–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, R.A.; Hookey, L.; Armstrong, D.; Bernstein, C.N.; Heitman, S.J.; Teshima, C.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Tse, F.; Sadowski, D. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Use of Video Capsule Endoscopy. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, N.; Inavolu, P.; Jagtap, N.; Singh, A.P.; Kalapala, R.; Memon, S.F.; Katukuri, G.R.; Pal, P.; Nabi, Z.; Ramchandani, M.; et al. Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy: Experience from a single large tertiary care centre. Endosc. Int. Open 2023, 11, E623–E628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurin, J.C.; Delvaux, M.; Gaudin, J.L.; Fassler, I.; Villarejo, J.; Vahedi, K.; Bitoun, A.; Canard, J.M.; Souquet, J.C.; Ponchon, T.; et al. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: Blinded comparison with video push-enteroscopy. Endoscopy 2003, 35, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, A.K.; Chin, B.W.; Meredith, C.G. Clinically significant small-bowel pathology identified by double-balloon enteroscopy but missed by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006, 64, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baichi, M.M.; Arifuddin, R.M.; Mantry, P.S. Small-bowel masses found and missed on capsule endoscopy for obscure bleeding. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postgate, A.; Despott, E.; Burling, D.; Gupta, A.; Phillips, R.; O’Beirne, J.; Patch, D.; Fraser, C. Significant small-bowel lesions detected by alternative diagnostic modalities after negative capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008, 68, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenka, M.K.; Majumder, S.; Kumar, S.; Sethy, P.K.; Goenka, U. Single center experience of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, F.; McNamara, D. Small-Bowel Capsule Endoscopy-Optimizing Capsule Endoscopy in Clinical Practice. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.R.; Hong, K.Y.; Chung, W.C. Factors Affecting Diagnostic Yields of Capsule Endoscopy for Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olano, C.; Pazos, X.; Avendaño, K.; Calleri, A.; Ketzoian, C. Diagnostic yield and predictive factors of findings in small-bowel capsule endoscopy in the setting of iron-deficiency anemia. Endosc. Int. Open 2018, 6, E688–E693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepileur, L.; Dray, X.; Antonietti, M.; Iwanicki-Caron, I.; Grigioni, S.; Chaput, U.; Di-Fiore, A.; Alhameedi, R.; Marteau, P.; Ducrotté, P.; et al. Factors associated with diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding by video capsule enteroscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Schoen, R.E.; Slivka, A. Diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes of capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2004, 60, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delvaux, M.; Fassler, I.; Gay, G. Clinical usefulness of the endoscopic video capsule as the initial intestinal investigation in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: Validation of a diagnostic strategy based on the patient outcome after 12 months. Endoscopy 2004, 36, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurin, J.C.; Delvaux, M.; Vahedi, K.; Gaudin, J.L.; Villarejo, J.; Florent, C.; Gay, G.; Ponchon, T. Clinical impact of capsule endoscopy compared to push enteroscopy: 1-year follow-up study. Endoscopy 2005, 37, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccioni, M.E.; Urgesi, R.; Cianci, R.; Rizzo, G.; D’Angelo, L.; Marmo, R.; Costamagna, G. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding reliable: Recurrence of bleeding on long-term follow-up. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 4520–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziatzios, G.; Gkolfakis, P.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Triantafyllou, K. Antithrombotic Treatment Is Associated with Small-Bowel Video Capsule Endoscopy Positive Findings in Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viazis, N.; Christodoulou, D.; Papastergiou, V.; Mousourakis, K.; Kozompoli, D.; Stasinos, G.; Dimopoulou, K.; Apostolopoulos, P.; Fousekis, F.; Liatsos, C.; et al. Diagnostic Yield and Outcomes of Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Small Bowel Bleeding Receiving Antithrombotics. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevinho, M.M.; Pinho, R.; Rodrigues, A.; Ponte, A.; Afecto, E.; Correia, J.; Freitas, T. Very High Yield of Urgent Small-Bowel Capsule Endoscopy for Ongoing Overt Suspected Small-Bowel Bleeding Irrespective of the Usual Predictive Factors. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lesion Type | Bleeding Potential | Example |

|---|---|---|

| P0 | None | Visible submucosal vein Diverticula without blood Nodule without mucosal breaks Erythematous patch |

| P1 | Uncertain | Red spots Small or isolated erosions |

| P2 | High | Angioectasia Large ulcers Tumors Varices |

| Variable | Results |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 129 (61.4) |

| Female | 81 (38.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.9 (18.5) |

| Indications, n (%) * | |

| Overt Obscure GI bleeding | 149 (70.9) |

| Occult Obscure GI bleeding | 60 (28.6) |

| Abnormal imaging | 3 (1.4) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 9 (4.3) |

| Other GI symptoms | 16 (7.6) |

| Adequate bowel preparation, n (%) | 185 (88.1) |

| Small bowel transit time, min (SD) | 282.3 (134.3) |

| Capsule endoscopy completion, n (%) | 194 (92.4) |

| Capsule endoscopy retention, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Capsule endoscopy complications, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Variable | Results |

|---|---|

| Vascular lesion in small bowel | 84 (40.0) |

| Small bowel erosion | 48 (22.9) |

| Small bowel ulcer | 48 (22.9) |

| Small bowel mucosal abnormality | 29 (13.8) |

| Red spots in small bowel | 16 (7.6) |

| Small bowel stricture | 8 (3.8) |

| Small bowel submucosal lesion | 6 (2.9) |

| Small bowel polyp | 1 (0.50) |

| Small bowel mass | 1 (0.50) |

| Blood in small bowel | 38 (18.1) |

| Saurin classification ** | |

| P0 | 67 (31.9) |

| Normal | 54 (25.7) |

| Erythematous patch only | 13 (6.2) |

| P1 | 13 (6.2) |

| Red spot | 10 (4.8) |

| Erosion with erythematous patch | 3 (1.4) |

| P2 | 130 (61.9) |

| Vascular lesion | 84 (40.0) |

| Small bowel ulcer | 26 (12.4) |

| Small bowel stricture | 8 (3.8) |

| Small bowel mass/polyp | 8 (3.8) |

| Blood in small bowel | 4 (1.9) |

| Altered management | 147 (70) |

| Post-CE Procedures | Results |

|---|---|

| Endoscopy | 8 (5.4) |

| Colonoscopy | 17 (11.6) |

| Push enteroscopy | 38 (25.9) |

| Double balloon enteroscopy | 31 (21.1) |

| Medical treatment | 53 (36.1) |

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odd Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | Odd Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| Older age (Age ≥ 60 years) | 1.52 (0.88–2.73) | 0.2 | 1.47 (0.83–2.58) | 0.2 |

| Male gender | 1.40 (0.80–2.48) | 0.3 | 1.37 (0.78–2.43) | 0.3 |

| Melena | 2.25 (1.10–4.42) | 0.04 | 2.10 (1.03–4.30) | 0.04 |

| Fresh blood per rectum | 0.63 (0.20–2.23) | 0.4 | 0.60 (0.17–2.17) | 0.4 |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 1.10 (0.50–2.1) | 0.9 | 1.04 (0.54–1.98) | 0.9 |

| Abnormal radiological imaging | 1.34 (0.10–14.58) | 0.8 | 1.29 (0.11–14.55) | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alali, A.A.; Alrashidi, R.; Allahow, F.; Dangi, A.; Alfadhli, A. Predictive Factors of Significant Findings on Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Suspected Small Bowel Bleeding. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14212352

Alali AA, Alrashidi R, Allahow F, Dangi A, Alfadhli A. Predictive Factors of Significant Findings on Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Suspected Small Bowel Bleeding. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(21):2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14212352

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlali, Ali A., Reem Alrashidi, Farah Allahow, Abhijit Dangi, and Ahmad Alfadhli. 2024. "Predictive Factors of Significant Findings on Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Suspected Small Bowel Bleeding" Diagnostics 14, no. 21: 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14212352

APA StyleAlali, A. A., Alrashidi, R., Allahow, F., Dangi, A., & Alfadhli, A. (2024). Predictive Factors of Significant Findings on Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Suspected Small Bowel Bleeding. Diagnostics, 14(21), 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14212352