Repetitive Self-Inflicted Craniocerebral Injury in a Patient with Antisocial Personality Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Report

3. Material and Methods

4. Discussions

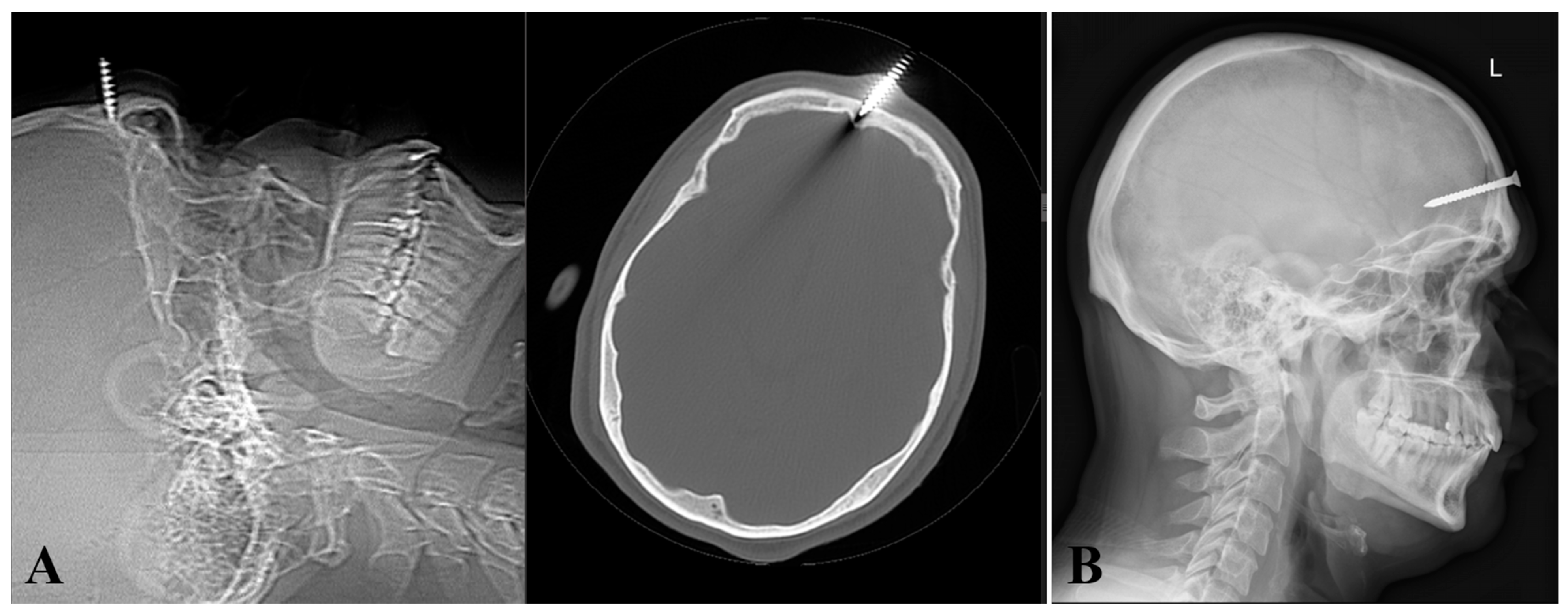

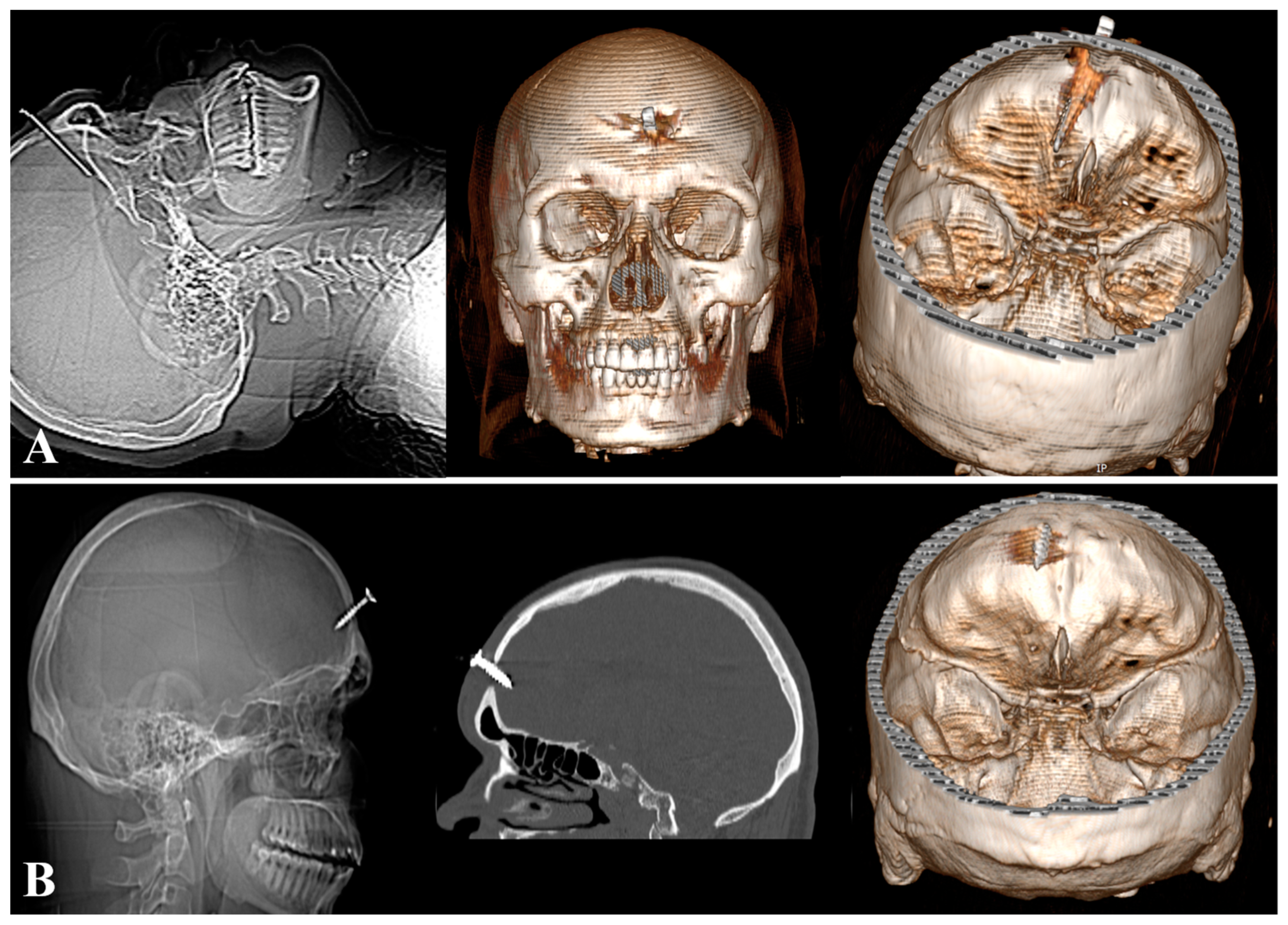

4.1. Imaging

4.2. Treatment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Large, M.; Babidge, N.; Nielssen, O. Intracranial Self-Stabbing. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2012, 33, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, L.; Sreenivasan, S.; Gross, E.; Markowitz, E.; Gross, B. Psychological Factors in the Determination of Suicide in Self-Inflicted Gunshot Head Wounds. J. Forensic Sci. 2000, 45, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, B.S.; Simpson, B.A.; Hatfield, R.H. Recurrent Self-Inflicted Craniocerebral Injury: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Br. J. Neurosurg. 1997, 11, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, K.A.; Dickman, C.A.; Smith, K.A.; Kinder, E.J.; Zabramski, J.M. Self-Inflicted Orbital and Intracranial Injury with a Retained Foreign Body, Associated with Psychotic Depression: Case Report and Review. Surg. Neurol. 1993, 40, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemphill, R.E. Attempted Suicide by Hammering a Nail into the Brain. S. Afr. Med. J. 1980, 57, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwarzschild, M. Nail in the Brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 620. [Google Scholar]

- Large, M.; Babidge, N.; Andrews, D.; Storey, P.; Nielssen, O. Major Self-Mutilation in the First Episode of Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2009, 35, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, M.J.; Monteith, S.J.; Macdonald, G. Nailed: The Case of 24 Self-Inflicted Intracranial Nails from a Pneumatic Nailgun. J. Trauma 2010, 68, E104–E107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, J.M.; Lebovitz, J.J.; Eller, J.L.; Coppens, J.R.; Bucholz, R.D.; Abdulrauf, S.I. Management of Nonmissile Penetrating Brain Injuries: A Description of Three Cases and Review of the Literature. Skull Base Rep. 2011, 1, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereggen, L.; Biétry, D.; Kottke, R.; Andres, R.H. Intracranial Foreign Body in a Patient With Paranoid Schizophrenia. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, e685–e687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Vavvas, D.; Asaad, W.F. Case 15-2015—A 27-Year-Old Man with a Nail in the Eye. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghabiklooei, A.; Molahoseini, R.; Khajoo, A.; Shiva, H. Multiple Nails in the Brain: An Unusual Suicidal Attempt. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2012, 33, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishore, K.; Sahu, S.; Bharti, P.; Dahiya, S.; Kumar, A.; Agarwal, A. Management of Unusual Case of Self-Inflicted Penetrating Craniocerebral Injury by a Nail. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock 2010, 3, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, S.; Kang, D.-H.; Kim, B.-H.; Choi, N.-C. Incidentally Discovered a Self-Inflicted a Nail in the Brain of Schizophrenia Patient. Psychiatry Investig. 2011, 8, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuh, S.-J.; Alaqeel, A. Ten Self-Inflicted Intracranial Penetrating Nail Gun Injuries. Neurosci. Riyadh Saudi Arab. 2015, 20, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriades, A.K.; Papadopoulos, M.C. Penetrating Head Injury in Planned and Repetitive Deliberate Self-Harm. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007, 82, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Martin, P.; Prat, S.; Bouyssy, M.; Sarraj, S.; O’Byrne, P. An Unusual Death by Transcranial Stab Wound: Homicide or Suicide? Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2008, 29, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frierson, R.L.; Lippmann, S.B. Psychiatric Consultation for Patients with Self-Inflicted Gunshot Wounds. Psychosomatics 1990, 31, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, L.; Hawton, K.; Simkin, S.; Turnbull, P.; Kapur, N.; Bennewith, O.; Gunnell, D. Gunshot Suicides in England—A Multicentre Study Based on Coroners’ Records. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2005, 40, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukube, S.; Hayashi, T.; Ishida, Y.; Kamon, H.; Kawaguchi, M.; Kimura, A.; Kondo, T. Retrospective Study on Suicidal Cases by Sharp Force Injuries. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2008, 15, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Nuernberg, A.; Rabinovici, R. Self-Inflicted Abdominal Stab Wounds. Injury 2003, 34, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, O.; Karadag, A.; Ozer, F.D.; Camlar, M.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Bozkurt, B.; Senoglu, M. A Rare History: An Intracranial Nail Present for Over a Half-Century. Acta Medica 2017, 60, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljunggren, B.; Strömblad, L.G. The Good Old Method of the Nail. Surg. Neurol. 1977, 7, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, K.R.; Schineller, T.M.; Tobia, A.; Schneider, J.A.; Bagayogo, I.P. Hypersexuality after Self-Inflicted Nail Gun Penetrating Traumatic Brain Injury and Neurosurgery: Case Analysis with Literature Review. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Acad. Clin. Psychiatr. 2015, 27, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, L.M.; Berrizbeitia, L.D.; Ordia, J. Crowbar Impalement of the Brain. J. Trauma 1985, 25, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gökçek, C.; Erdem, Y.; Köktekir, E.; Karatay, M.; Bayar, M.A.; Edebali, N.; Kiliç, C. Intracranial Foreign Body. Turk. Neurosurg. 2007, 17, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karabatsou, K.; Kandasamy, J.; Rainov, N.G. Self-Inflicted Penetrating Head Injury in a Patient with Manic-Depressive Disorder. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2005, 26, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, K.; Richards, P.J.; Oakley, P.A. Self-Inflicted Transcranial Stab Wound of the Pons. Injury 2002, 33, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, B.K.; el-Dosoky, A.; Barrett, J.S. Self-Inflicted Intracranial Injury. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 1994, 164, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Nakamura, N.; Sugishita, M.; Kato, Y.; Iwata, M. Partial Disconnection Syndrome Following Penetrating Stab Wound of the Brain. Eur. Neurol. 1986, 25, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, L.C.; Winestock, D.P.; Hoff, J.T. Stab Wounds of the Brain. West. J. Med. 1977, 126, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.L.; Branch, J.W. Intracranial Nail-Sets. An Unusual Self-Inflicted Foreign Body. Case Report. Acta Neurochir. 1971, 24, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azariah, R.G. An Unusual Metallic Foreign Body within the Brain. Case Report. J. Neurosurg. 1970, 32, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, D.L. Penetrating Craniocerebral Injuries. Report of Two Unusual Cases. J. Neurosurg. 1965, 23, 204–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, C.T.; Orjiaku, M.E. Management of a Nail Impalement Injury to the Brain in a Non-Neurosurgical Centre: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 2016, 19, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Bari, M.-E. Suicide Bomb Attack Causing Penetrating Craniocerebral Injury. Chin. J. Traumatol. Zhonghua Chuang Shang Za Zhi 2013, 16, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Awori, J.; Wilkinson, D.A.; Gemmete, J.J.; Thompson, B.G.; Chaudhary, N.; Pandey, A.S. Penetrating Head Injury by a Nail Gun: Case Report, Review of the Literature, and Management Considerations. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2017, 26, e143–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvack, Z.N.; Hunt, M.A.; Weinstein, J.S.; West, G.A. Self-Inflicted Nail-Gun Injury with 12 Cranial Penetrations and Associated Cerebral Trauma. Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 104, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Arita, T.; Kumate, S.; Yoshinaga, S. [Penetrating head injury caused by weed—Case report]. No To Shinkei 1995, 47, 1192–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Pk, A.; Gp, D.; Er, L. An Historical Context of Modern Principles in the Management of Intracranial Injury from Projectiles. Neurosurg. Focus 2010, 28, E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.J.; Pople, I.; Cummins, B.H. Unusual Craniocerebral Penetrating Injury by a Power Drill: Case Report. Surg. Neurol. 1992, 38, 471–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.F.; Brodkey, J.S.; Colombi, B.J. The Danger of Intracranial Wood. Surg. Neurol. 1977, 7, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bakay, L.; Glasauer, F.E.; Grand, W. Unusual Intracranial Foreign Bodies. Report of Five Cases. Acta Neurochir. 1977, 39, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwair, S.M.; Singh, R.G.; Dharker, S.R.; Chaurasia, B.D. Unusual Craniocerebral Injury by a Key. Surg. Neurol. 1978, 9, 267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chandran, A.S.; Honeybul, S. A Case of Psychosis Induced Self-Insertion of Intracranial Hypodermic Needles Causing Seizures. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015, 2015, rju145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, J.; Jensen, H.P. Intracranial Sewing Needles, an Unusual Cause of Headaches. Zentralbl. Neurochir. 1958, 18, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hargitai, R.; Kassai, A.; Udvardy, O. Cerebral Abscess in Infant Caused by Sewing Needle. Orv. Hetil. 1957, 98, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sturiale, C.L.; Massimi, L.; Mangiola, A.; Pompucci, A.; Roselli, R.; Anile, C. Sewing Needles in the Brain: Infanticide Attempts or Accidental Insertion? Neurosurgery 2010, 67, E1170–E1179, discussion E1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balak, N.; Güçlü, G.; Karaca, I.; Aksoy, S. Intracranially Retained Sewing Needle in a Child: Does the Rust on the Needle Have Any Implication? Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. Off. Publ. Eur. Trauma Soc. 2008, 34, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yürekli, V.A.; Doğan, M.; Kutluhan, S.; Koyuncuoglu, H.R. Status Epilepticus in a 52-Year-Old Woman Due to Intracranial Needle. Seizure 2012, 21, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notermans, N.C.; Gooskens, R.H.; Tulleken, C.A.; Ramos, L.M. Cranial Nerve Palsy as a Delayed Complication of Attempted Infanticide by Insertion of a Stylet through the Fontanel. Case Report. J. Neurosurg. 1990, 72, 818–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Age/Gender | Foreign Body | Psychiatric Diagnosos | Medical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saint-Martin et al., 2008 [17] | 24/M | Knife | Schizophrenia | Death |

| Gökçek C et al., 2007 [26] | 20/M | Nail | No data | Recovered |

| Karabatsou et al., 2005 [27] | 32/M | Wire | Bipolar affective disorder | Recovered |

| Mitra et al., 2002 [28] | 24/M | Knife | Schizophrenia | Recovered |

| Musa et al., 1997 [3] | 28/M | Nail | Personality disorder | Epilepsy |

| Puri et al., 1994 [29] | 30/M | Nail | Psychosis | Recovered |

| Abe et al., 1986 [30] | 25/M | Ice pick | Depression | Recovered |

| Dempsey and Hoff, 1977 [31] | 27/M | Knife | Schizophrenia | Recovered |

| Fox and Branch, 1971 [32] | 50/M | Two nails | Depression | Motor deficit |

| Azariah, 1970 [33] | 19/M | Three wires | Unknown | Death |

| Reeves, 1965 [34] | Adult/F | Nail | Psychosis | Death |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cucu, A.I.; Costea, C.F.; Silișteanu, S.C.; Blaj, L.A.; Istrate, A.C.; Patrascu, R.E.; Hartie, V.L.; Patrascanu, E.; Turliuc, M.D.; Turliuc, S.; et al. Repetitive Self-Inflicted Craniocerebral Injury in a Patient with Antisocial Personality Disorder. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14141549

Cucu AI, Costea CF, Silișteanu SC, Blaj LA, Istrate AC, Patrascu RE, Hartie VL, Patrascanu E, Turliuc MD, Turliuc S, et al. Repetitive Self-Inflicted Craniocerebral Injury in a Patient with Antisocial Personality Disorder. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(14):1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14141549

Chicago/Turabian StyleCucu, Andrei Ionut, Claudia Florida Costea, Sînziana Călina Silișteanu, Laurentiu Andrei Blaj, Ana Cristina Istrate, Raluca Elena Patrascu, Vlad Liviu Hartie, Emilia Patrascanu, Mihaela Dana Turliuc, Serban Turliuc, and et al. 2024. "Repetitive Self-Inflicted Craniocerebral Injury in a Patient with Antisocial Personality Disorder" Diagnostics 14, no. 14: 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14141549

APA StyleCucu, A. I., Costea, C. F., Silișteanu, S. C., Blaj, L. A., Istrate, A. C., Patrascu, R. E., Hartie, V. L., Patrascanu, E., Turliuc, M. D., Turliuc, S., Sava, A., & Boişteanu, O. (2024). Repetitive Self-Inflicted Craniocerebral Injury in a Patient with Antisocial Personality Disorder. Diagnostics, 14(14), 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14141549