A Logistic Regression Model for Biomechanical Risk Classification in Lifting Tasks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. IMU-Based Wearable System: The Mobility Lab System

2.2. Revised NIOSH Lifting Equation

- LC: Load Constant 25/20 kg (males, <45/>45 years old, respectively), 20/15 kg (females, <45/>45 years old, respectively);

- HM: Horizontal Multiplier;

- VM: Vertical Multiplier;

- DM: Distance Multiplier;

- AM: Asymmetric Multiplier;

- FM: Frequency Multiplier;

- GM: Grab Multiplier.

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Study Protocol

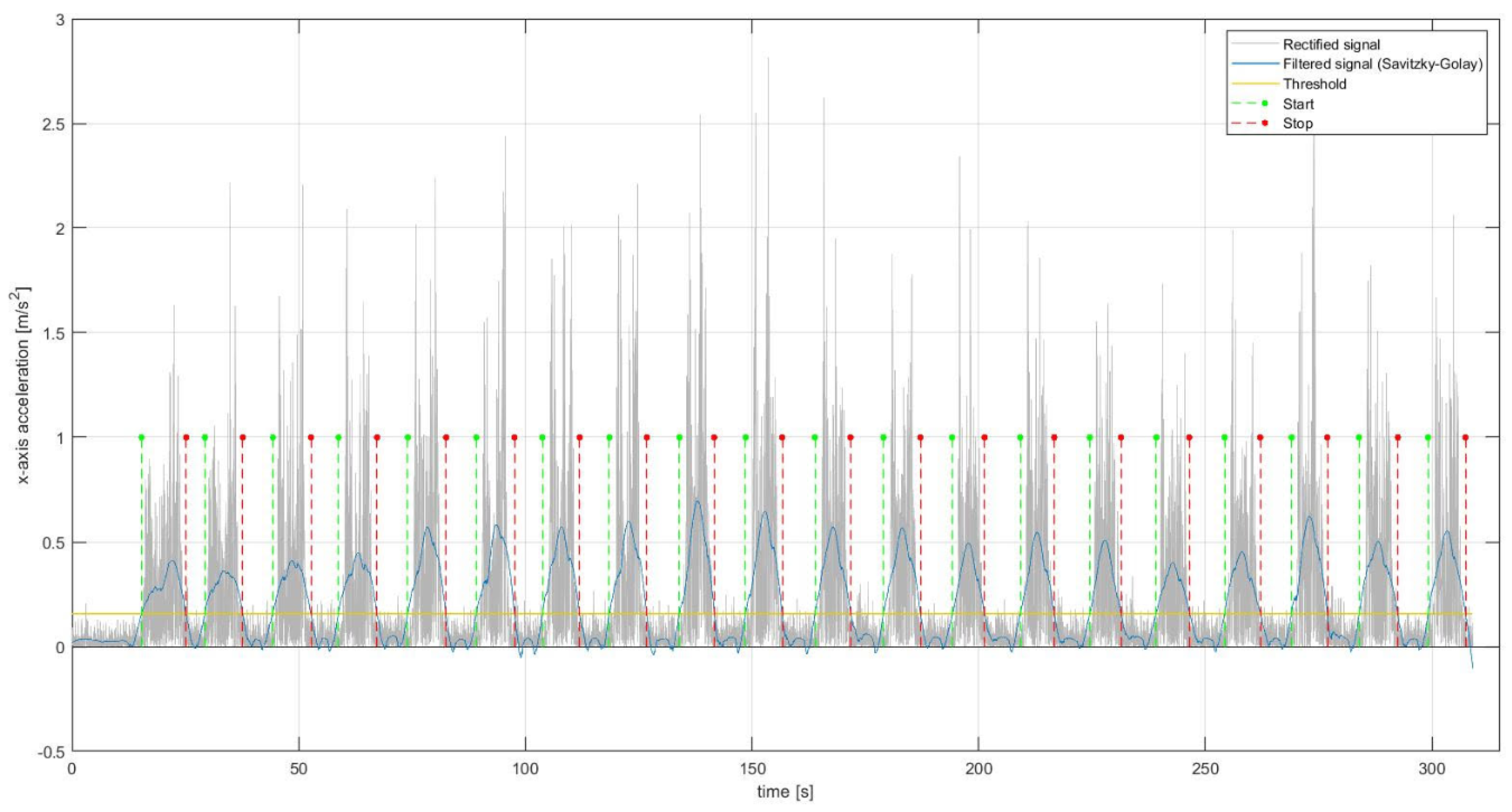

2.5. Feature Extraction

- Rectified signal area (RSA) [m/s];

- Peak to peak amplitude (PPA) [m/s2];

- Mean (MEAN) [m/s2];

- Standard Deviation (SD) [m/s2];

- Harmonic mean (HM) [m/s2];

- 25-percentile (25P) [m/s2];

- 75-percentile (75P) [m/s2];

- Zero-crossing (ZC) [adim];

- Cumulative length (CL) [m/s2];

- Fractal dimension (FD) [adim];

- Number of slope changes (NSC) [adim].

- Entropy (EN) [adim];

- Kurtosis (KU) [adim];

- Skewness (SK) [adim];

- Power (POW) [m/s2];

- Median frequency (MDF) [Hz];

- Mean frequency (MNF) [Hz];

- Peak of the power spectrum (PPS) [m/s];

- Peak frequency (PF) [Hz].

2.6. Statistical Learning Analysis

- Absence of multicollinearity;

- Absence of outliers;

- Ratio between the sample size of the smallest class and the number of independent variables (the features extracted) greater than 10 [44].

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da Costa, B.R.; Vieira, E.R. Risk factors for work--related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, B.P.; Putz-Anderson, V. Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors—A Critical Review of Epidemiologic Evidence for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck, Upper Extremity, and Low Back; DHHS (NIOSH) Publication: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1997; pp. 97–141. [Google Scholar]

- Winkel, J.; Mathiassen, S.E. Assessment of physical work load in epidemiologic studies: Concepts, issues and operational considerations. Ergonomics 1994, 37, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAtamney, L.; Corlett, E.N. RULA: A survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Appl. Ergon. 1993, 24, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hignett, S.; McAtamney, L. Rapid entire body assessment (REBA). App. Ergon. 2000, 31, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battevi, N.; Menoni, O.; Ricci, M.G.; Cairoli, S. MAPO index for risk assessment of patient manual handling in hospital wards: A validation study. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.R.; Putz-Anderson, V.; Garg, A.; Fine, L.J. Revised NIOSH equation for the design and evaluation of manual lifting tasks. Ergonomics 1993, 36, 749–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G.; Coccia, A.; Panigazzi, M.; Capodaglio, E.M.; D’Addio, G. Work-related risk assessment according to the revised NIOSH lifting equation: A preliminary study using a wearable inertial sensor and machine learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Ma, L.; Tsao, L.; Zhang, Z. Continuous measurement of muscle fatigue using wearable sensors during light manual operations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Orlando, FI, USA, 26–31 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, S.; Hashizume, H. Questions to improve quality of life with wearables: Humans, technology, and the world. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Hybrid Information Technology, Cheju, Korea, 9–11 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khakurel, J.; Melkas, H.; Porras, J. Tapping into the wearable device revolution in the work environment: A systematic review. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 31, 791–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefana, E.; Marciano, F.; Rossi, D.; Cocca, P.; Tomasoni, G. Wearable devices for ergonomics: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2021, 21, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, H.; Burch, R.F.; Talegaonkar, P.; Saucier, D.; Luczak, T.; Ball, J.E.; Turner, A.; Arachchige, S.N.K.K.; Carrol, W.; Smith, B.K.; et al. Wearable stretch sensors for human movement monitoring and fall detection in ergonomics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schall Jr, M.C.; Sesek, R.F.; Cavuoto, L.A. Barriers to the adoption of wearable sensors in the workplace: A survey of occupational safety and health professionals. Hum. Factors 2018, 60, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, I.; Mileti, I.; Del Prete, Z.; Palermo, E. Measuring Biomechanical Risk in Lifting Load Tasks Through Wearable System and Machine-Learning Approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranavolo, A.; Draicchio, F.; Varrecchia, T.; Silvetti, A.; Iavicoli, S. Wearable Monitoring Devices for Biomechanical Risk Assessment at Work: Current Status and Future Challenges—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; D’Souza, C. A narrative review on contemporary and emerging uses of inertial sensing in occupational ergonomics. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020, 76, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V.C.; Ross, G.B.; Clouthier, A.L.; Fischer, S.L.; Graham, R.B. The role of machine learning in the primary prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A scoping review. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 98, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, J.G.; Capanema, D.D.O.; de Souza, T.V.; Serrão, J.C.; Machado Pereira, A.C.; Nassis, G.P. Current approaches to the use of artificial intelligence for injury risk assessment and performance prediction in team sports: A systematic review. Sports Med-Int. Open 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzandipour, M.; Nabovati, E.; Saeedi, S.; Fakharian, E. Fuzzy decision support systems to diagnose musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic literature review. Comput. Methods Program Biomed. 2018, 163, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Maiti, J. Machine learning in occupational accident analysis: A review using science mapping approach with citation network analysis. Saf. Sci. 2020, 131, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallmuur, K. Machine learning approaches to analysing textual injury surveillance data: A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 79, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, T.R.; Bernard, B.P. Epidemiology of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1996, 27, 679–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.R. Revised NIOSH lifting equation. In Biomechanics in Ergonomics, 2nd ed.; Kumar, S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 531–564. [Google Scholar]

- Donisi, L.; Pagano, G.; Cesarelli, G.; Coccia, A.; Amitrano, F.; D’Addio, G. Benchmarking between two wearable inertial systems for gait analysis based on a different sensor placement using several statistical approaches. Measurement 2021, 173, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Horak, F.B. Potential of APDM mobility lab for the monitoring of the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2016, 13, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.; Stuart, S.; McBarron, G.; Fino, P.C.; Mancini, M.; Curtze, C. Validity of Mobility Lab (version 2) for gait assessment in young adults, older adults and Parkinson’s disease. Physiol. Meas. 2019, 40, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz-Hübsch, T.; Brandt, A.U.; Pfueller, C.; Zange, L.; Seidel, A.; Kühn, A.A.; Paul, F.; Minnerop, M.; Doss, S. Accuracy and repeatability of two methods of gait analysis—GaitRite™ und Mobility Lab™—In subjects with cerebellar ataxia. Gait Posture 2016, 48, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, G.; D’Addio, G.; De Campi, M.; Donisi, L.; Biancardi, A.; Cesarelli, M. Rehabilitation Outcome in Patients undergone Hip or Knee Replacement Surgery using Inertial Technology for Gait Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Bari, Italy, 1 June–1 July 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- D’Addio, G.; Donisi, L.; Pagano, G.; Improta, G.; Biancardi, A.; Cesarelli, M. Agreement between opal and G-walk wearable inertial systems in gait analysis on normal and pathological subjects. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia, A.; Lanzillo, B.; Donisi, L.; Amitrano, F.; Cesarelli, G.; D’Addio, G. Repeatability of Spatio-Temporal Gait Measurements in Parkinson’s Disease. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Bary, Italy, 1 June–1 July 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G.; Balbi, P.; Provitera, V.; Lanzillo, B.; Coccia, A.; D’Addio, G. Positive impact of short-term gait rehabilitation in Parkinson patients: A combined approach based on statistics and machine learning. MBE 2021, 18, 6995–7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; King, L.; Salarian, A.; Holmstrom, L.; McNames, J.; Horak, F.B. Mobility lab to assess balance and gait with synchronized body-worn sensors. J. Bioeng. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 12 (Suppl. 1), 007. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, S.; Joyce, J.; Biskis, A.; Parulekar, M.; Armijo, N.; Zampieri, C.; Tracy, R.; Palmer, A.S.; Fefferman, M.; Ouyang, B.; et al. Normative database of spatiotemporal gait parameters using inertial sensors in typically developing children and young adults. Gait Posture 2020, 80, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Z. Reference values of gait using APDM movement monitoring inertial sensor system. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 170818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.R.; Lu, M.-L.; Piacitelli, L.A.; Werren, D.; Deddens, J.A. Efficacy of the Revised NIOSH Lifting Equation to Predict Risk of Low Back Pain Due to Manual Lifting. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.L.; Waters, T.R.; Krieg, E.; Werren, D. Efficacy of the revised NIOSH lifting equation to predict risk of low-back pain associated with manual lifting: A one-year prospective study. Hum. Factors 2014, 56, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.R.; Baron, S.L.; Piacitelli, L.A.; Anderson, V.P.; Skov, T.; Haring-Sweeney, M.; Wall, D.K.; Fine, L.J. Evaluation of the Revised NIOSH Lifting Equation. Spine 1999, 24, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, J.T.; Lieblich, M.; Bao, S.; McQuade, K.; Hughes, M. Automation of Workplace Lifting Hazard Assessment for Musculoskeletal Injury Prevention. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 26, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A. Savitzky--Golay smoothing filters. Comput. Phys. 1990, 4, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrutinio, D.; Ricciardi, C.; Donisi, L.; Losavio, E.; Battista, P.; Guida, P.; Cesarelli, M.; Pagano, G.; D’Addio, G. Machine learning to predict mortality after rehabilitation among patients with severe stroke. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- D’Addio, G.; Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G.; Amitrano, F.; Coccia, A.; La Rovere, M.T.; Ricciardi, C. Extracting Features from Poincaré Plots to Distinguish Congestive Heart Failure Patients According to NYHA Classes. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donisi, L.; Ricciardi, C.; Cesarelli, G.; Coccia, A.; Amitrano, F.; Adamo, S.; D’addio, G. Bidimensional and Tridimensional Poincaré Maps in Cardiology: A Multiclass Machine Learning Study. Electronics 2022, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.; de Groot, J.A.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Reitsma, J.B. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 2455–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrecchia, T.; De Marchis, C.; Rinaldi, M.; Draicchio, F.; Serrao, M.; Schmid, M.; Conforto, S.; Ranavolo, A. Lifting activity assessment using surface electromyographic features and neural networks. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrecchia, T.; De Marchis, C.; Draicchio, F.; Schmid, M.; Conforto, S.; Ranavolo, A. Lifting Activity Assessment Using Kinematic Features and Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranavolo, A.; Varrecchia, T.; Iavicoli, S.; Marchesi, A.; Rinaldi, M.; Serrao, M.; Conforto, S.; Cesarelli, M.; Draicchio, F. Surface electromyography for risk assessment in work activities designed using the e “revisedNIOSH lifting equation”. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 68, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiyanselage, S.E.; Nguyen, P.H.D.; Rajabi, M.S.; Akhavian, R. Automated workers’ ergonomic risk assessment in manual material handling using sEMG wearable sensors and machine learning. Electronics 2021, 10, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donisi, L.; Capodaglio, E.M.; Pagano, G.; Amitrano, F.; Cesarelli, M.; Panigazzi, M.; D’Addio, G. Feasibility of Tree-based Machine Learning algorithms fed with surface electromyographic features to discriminate risk classes according to NIOSH. In Proceeding of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Messina, Italy, 22–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, M.; Madeleine, P.; Samani, A.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Skals, S.; Vinstrup, J.; Andersen, L.L. Accuracy of identification of low or high risk lifting during standardised lifting situations. Ergonomics 2017, 61, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Sex | 6 male, 7 female |

| Age [years] | 39.31 ± 12.72 |

| Weight [kg] | 67.31 ± 11.35 |

| Height [cm] | 171.50 ± 9.13 |

| Manual laterality | 10 right, 3 left |

| Subject Sex and Age | Load Weight [kg] | Lifting Frequency [Lifting/min] | Vertical Displacement (Start–End) 1 [cm] | LI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male < 45 | 6.5 | 4 | 70–120 | 0.57 |

| Male > 45 | 5.5 | 4 | 70–120 | 0.60 |

| Female | 3.5 | 4 | 70–120 | 0.50 |

| Subject Sex and Age | Load Weight [kg] | Lifting Frequency [Lifting/min] | Vertical Displacement (Start–End) 1 [cm] | LI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male < 45 | 12.5 | 4 | 20–120 | 1.48 |

| Male > 45 | 10.5 | 4 | 20–120 | 1.55 |

| Female | 10.5 | 4 | 70–120 | 1.64 |

| Features * | NO RISK Mean ± Std | RISK Mean ± Std | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSAax | 405.33 ± 110.37 | 464.06 ± 116.47 | <0.001 |

| PPAax | 4.15 ± 1.47 | 4.79 ± 1.26 | <0.001 |

| SDax | 0.57 ± 0.17 | 0.64 ± 0.14 | <0.001 |

| HMax | 0.44 ± 5.47 | 0.87 ± 19.09 | 0.1340 |

| 75Pax | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| 25Pax | −0.26 ± 0.06 | −0.31 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| MEANax | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| ZCax | 78.71 ± 20.28 | 84.75 ± 21.76 | <0.001 |

| CLax | 75.50 ± 24.03 | 99.72 ± 26.92 | <0.001 |

| FDax | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | <0.001 |

| NSCax | 319.31 45.20 | 324.22 50.43 | 0.0076 |

| ENax | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| KUax | 132.80 59.07 | 118.81 59.99 | <0.001 |

| SKax | 10.31 ± 2.27 | 9.58 ± 2.39 | <0.001 |

| POWax | 186.96 109.31 | 228.56 116.66 | <0.001 |

| MDFax | 1.87 ± 0.51 | 2.20 ± 0.71 | <0.001 |

| MNFax | 3.01 ± 0.94 | 3.66 ± 1.10 | <0.001 |

| PPSax | 21.21 ± 15.03 | 21.89 ± 12.77 | 0.149 |

| PFax | 1.38 ± 0.27 | 1.53 0.35 | <0.001 |

| Features * | NO RISK Mean ± Std | RISK Mean ± Std | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSAay | 143.70 ± 44.34 | 182.36 ± 64.92 | <0.001 |

| PPAay | 1.60 ± 0.57 | 2.15 ± 0.75 | <0.001 |

| SDay | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | <0.001 |

| HMay | 0.05 ± 0.74 | 0.91 ± 8.13 | 0.939 |

| 75Pay | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| 25Pay | −0.09 ± 0.03 | −0.11 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| MEANay | 0.38 ± 0.10 | 0.44 ± 0.09 | <0.001 |

| ZCay | 138.27 ± 24.54 | 137.88 ± 23.58 | 0.6520 |

| Clay | 50.77 ± 17.97 | 64.91 ± 23.79 | <0.001 |

| FDay | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | <0.001 |

| NSCay | 412.34 ± 50.82 | 407.90 ± 56.37 | 0.9780 |

| ENay | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| KUay | 49.79 ± 31.04 | 48.03 ± 32.89 | 0.1230 |

| SKay | 5.85 ± 1.68 | 5.68 ± 1.76 | 0.0550 |

| POWay | 21.96 ± 15.90 | 36.68 ± 30.18 | <0.001 |

| MDFay | 5.41 ± 1.96 | 5.67 ± 2.11 | 0.0130 |

| MNFay | 6.85 ± 1.41 | 7.04 ± 1.59 | <0.001 |

| PPSay | 0.91 ± 0.65 | 1.52 ± 2.26 | <0.001 |

| PFay | 3.44 ± 2.71 | 3.62 ± 2.94 | 0.9600 |

| Features * | NO RISK Mean ± Std | RISK Mean ± Std | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSAaz | 260.34 ± 75.91 | 349.12 ± 89.93 | <0.001 |

| PPAaz | 3.12 ± 1.21 | 4.30 ± 1.48 | <0.001 |

| SDaz | 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.49 ± 0.13 | <0.001 |

| HMaz | 0.08 ± 1.23 | 0.08 ± 2.34 | 0.6760 |

| 75Paz | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| 25Paz | −0.16 ± 0.04 | −0.22 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| MEANaz | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | <0.001 |

| ZCaz | 119.74 ± 32.32 | 123.01 ± 37.84 | 0.0470 |

| CLaz | 79.73 ± 32.82 | 109.49 ± 39.40 | <0.001 |

| FDaz | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | <0.001 |

| NSCaz | 418.80 ± 51.49 | 420.51 ± 73.58 | 0.1560 |

| ENaz | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| KUaz | 143.35 ± 68.52 | 118.38 ± 60.15 | <0.001 |

| SKaz | 10.48 ± 2.62 | 9.39 ± 2.59 | <0.001 |

| POWaz | 74.16 ± 46.93 | 134.43 ± 83.27 | <0.001 |

| MDFaz | 3.21 ± 2.22 | 3.61 ± 2.67 | <0.001 |

| MNFaz | 5.21 ± 1.67 | 5.64 ± 1.91 | <0.001 |

| PPSaz | 7.01 ± 4.79 | 11.39 ± 9.24 | <0.001 |

| PFaz | 1.32 ± 0.24 | 1.63 ± 1.83 | 0.6950 |

| Features * | NO RISK Mean ± Std | RISK Mean ± Std | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSAvx | 44.04 ± 10.68 | 53.42 ± 13.44 | <0.001 |

| PPAvx | 0.46 ± 0.19 | 0.60 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

| SDvx | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| HMvx | 0.48 ± 7.14 | 0.07 ± 0.50 | 0.5010 |

| 75Pvx | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 25Pvx | −0.02 ± 0.01 | −0.03 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| MEANvx | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| ZCvx | 82.54 ± 18.53 | 89.13 ± 21.74 | <0.001 |

| CLvx | 10.16 ± 3.46 | 13.30 ± 4.15 | <0.001 |

| FDvx | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | <0.001 |

| NSCvx | 313.75 ± 44.28 | 321.82 ± 51.81 | 0.0030 |

| ENvx | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| KUvx | 125.56 ± 62.74 | 107.40 ± 54.84 | <0.001 |

| SKvx | 9.79 ± 2.37 | 8.96 ± 2.22 | <0.001 |

| POWvx | 1.94 ± 1.06 | 2.85 ± 1.35 | <0.001 |

| MDFvx | 2.36 ± 0.58 | 2.71 ± 0.76 | <0.001 |

| MNFvx | 3.87 ± 0.86 | 4.41 ± 1.01 | <0.001 |

| PPSvx | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 0.23 ± 0.14 | <0.001 |

| PFvx | 1.58 ± 0.38 | 1.67 ± 0.42 | 0.0010 |

| Features * | NO RISK Mean ± Std | RISK Mean ± Std | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSAvy | 109.69 ± 28.76 | 135.25 ± 34.67 | <0.001 |

| PPAvy | 1.34 ± 0.56 | 1.59 ± 0.69 | <0.001 |

| SDvy | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| HMvy | 0.21 ± 1.88 | −0.21 ± 4.16 | 0.5380 |

| 75Pvy | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| 25Pvy | −0.07 ± 0.02 | −0.09 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| MEANvy | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| ZCvy | 68.85 ± 24.58 | 74.23 ± 30.07 | <0.001 |

| CLvy | 22.95 ± 11.30 | 29.77 ± 10.97 | <0.001 |

| FDvy | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | <0.001 |

| NSCvy | 324.49 ± 52.89 | 334.78 ± 68.65 | <0.001 |

| ENvy | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| KUvy | 194.42 ± 74.38 | 199.58 ± 86.44 | 0.5540 |

| SKvy | 12.65 ± 2.63 | 12.77 ± 2.99 | 0.6830 |

| POWvy | 13.37 ± 7.19 | 19.71 ± 11.09 | <0.001 |

| MDFvy | 1.68 ± 0.52 | 1.86 ± 0.99 | 0.0140 |

| MNFvy | 3.20 ± 1.17 | 3.67 ± 1.43 | <0.001 |

| PPSvy | 1.97 ± 1.11 | 2.88 ± 1.95 | <0.001 |

| PFvy | 1.27 ± 0.18 | 1.24 ± 0.19 | 0.0460 |

| Features * | NO RISK Mean ± Std | RISK Mean ± Std | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSAvz | 32.94 ± 9.08 | 43.54 ± 13.65 | <0.001 |

| PPAvz | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 0.49 ± 0.16 | <0.001 |

| SDvz | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| HMvz | −0.01 ± 0.28 | −0.01 ± 0.25 | 0.2170 |

| 75Pvz | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 25Pvz | −0.02 ± 0.01 | −0.03 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| MEANvz | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| ZCvz | 75.30 ± 14.85 | 79.12 ± 17.35 | <0.001 |

| CLvz | 7.14 ± 2.29 | 10.08 ± 3.31 | <0.001 |

| FDvz | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | <0.001 |

| NSCvz | 284.87 ± 40.98 | 287.71 ± 46.58 | 0.0030 |

| ENvz | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| KUvz | 99.84 ± 49.40 | 98.46 ± 51.43 | 0.4540 |

| SKvz | 8.67 ± 2.10 | 8.50 ± 2.17 | 0.1970 |

| POWvz | 1.11 ± 0.62 | 2.00 ± 1.23 | <0.001 |

| MDFvz | 2.66 ± 0.69 | 2.92 ± 0.79 | <0.001 |

| MNFvz | 3.83 ± 0.66 | 4.24 ± 0.90 | <0.001 |

| PPSvz | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | <0.001 |

| PFvz | 1.72 ± 0.66 | 1.85 ± 0.78 | 0.0430 |

| NO RISK | RISK | Percentage of Correctness [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO RISK | 218 | 39 | 84.8 |

| RISK | 49 | 207 | 80.9 |

| Accuracy [%] | Sensitivity [%] | Specificity [%] |

|---|---|---|

| 82.8 | 84.8 | 80.9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G.; Capodaglio, E.; Panigazzi, M.; D’Addio, G.; Cesarelli, M.; Amato, F. A Logistic Regression Model for Biomechanical Risk Classification in Lifting Tasks. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2624. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112624

Donisi L, Cesarelli G, Capodaglio E, Panigazzi M, D’Addio G, Cesarelli M, Amato F. A Logistic Regression Model for Biomechanical Risk Classification in Lifting Tasks. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(11):2624. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112624

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonisi, Leandro, Giuseppe Cesarelli, Edda Capodaglio, Monica Panigazzi, Giovanni D’Addio, Mario Cesarelli, and Francesco Amato. 2022. "A Logistic Regression Model for Biomechanical Risk Classification in Lifting Tasks" Diagnostics 12, no. 11: 2624. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112624

APA StyleDonisi, L., Cesarelli, G., Capodaglio, E., Panigazzi, M., D’Addio, G., Cesarelli, M., & Amato, F. (2022). A Logistic Regression Model for Biomechanical Risk Classification in Lifting Tasks. Diagnostics, 12(11), 2624. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112624