1. Introduction

Rod mills typically consist about 30 rolling stands, including 13 roughing stands and 16–18 finishing stands, sequentially arranged to reduce a 160 mm square billet to a 5.5 mm diameter rod at elevated temperatures (950 °C and 1100 °C)—a common customer-specified rod product size [

1]. A rolling stand (or simply stand) is a functional unit consisting of a driving motor, housing, spindle, gearbox, and a pair of grooved rolls aligned in an upper–lower configuration.

Unlike hot strip mills, which usually consist of 2–4 roughing stands and 6–7 finishing stands [

2] and are equipped with load cells at each stand, most rod mills lack stand-by-stand load cells for direct roll force measurement. This absence is mainly due to two factors. First, installing and maintaining load cells across dozens of stands results in entails prohibitively high capital and operational costs. Second, rod rolling lines generally do not employ automatic gauge control (AGC) systems that adjust roll gaps in real time based on roll force feedback.

Nevertheless, roll force data in rod mill remains highly desirable. It supports optimized roll pass design, including precise roll gap settings for low-temperature rolling [

3]; and it enables early detection of abnormal roll wear [

4] and surface defects in the rolled material [

5]. However, retrofitting load cell systems into existing rod mills is practically infeasible due to structural complexity and unavoidable production downtime, even if cost is disregarded. Therefore, alternative approaches for torque and roll force estimation in rod mills are essential.

Research on indirect torque estimation in induction motors can be broadly classified into two categories: (1) sensorless methods, which estimate torque using only terminal quantities without additional torque or speed sensors, and (2) speed-sensor-based methods, in which torque is calculated from slip or from speed–torque characteristics.

In the first group, Bastiaensen et al. [

6] investigated the sensitivity of sensorless algorithms to parameter errors and measurement uncertainty in air-gap–based torque calculations, and proposed basic guidelines for evaluating sensorless torque estimation schemes. Aarniovuori et al. [

7] examined the accuracy achievable when torque is estimated solely from motor terminal voltage and current, and discussed the practical limits of such methods. More recently, Yamamoto and Hirahara [

8] presented a practical estimation method that incorporates stray-load loss into an equivalent-circuit model, enabling improved torque estimation without torque or speed meters.

In the second group, Hsu et al. [

9] introduced a simple slip-based torque calculation approach in the context of induction-motor efficiency evaluation. Yamazaki et al. [

10] improved torque prediction by considering speed-dependent stray-load loss and harmonic torque. Kawamura et al. [

11] further increased accuracy by simultaneously estimating rotor speed and stator resistance using a predictive algorithm.

These studies provide an important foundation for indirect torque estimation of induction motors. However, they primarily address general drive applications and do not explicitly consider torque or roll-force estimation under rolling-mill operating conditions. This limitation motivates the present work, in which we develop and validate a current- and rpm-based torque-conversion, in which we build and validate a current and rpm–torque conversion framework using a laboratory-scale rolling mill.

In this study, a laboratory-scale rolling mill driven by a three-phase induction motor and equipped with a proper measurement system was designed and fabricated to experimentally validate the proposed roll-force estimation framework. The system was configured to simultaneously measure motor current, roll rotational speed, and roll force, thereby enabling sequential conversion of the measured current into motor torque, roll torque, and ultimately roll force. Rolling tests were conducted under various rolling conditions, including different roll gaps and specimen widths. The motor current was converted into motor torque by applying the equivalent circuit model of an induction motor [

12,

13], which represents the electromagnetic behavior of the motor as a simplified single-phase network at rated frequency, capturing the relationships among input voltage, current, internal impedance, power losses, and magnetic flux. The roll torque is then obtained by applying the mechanical gear ratio between the motor and the rolls. Once the roll torque is then determined, the corresponding roll force is determined using the classical torque(lever)-arm model [

14], which assumes that the resultant roll pressure acts at a certain distance from the roll center.

The current–rpm–torque conversion framework proposed in this study is governed solely by the electromechanical characteristics of the drive system and is therefore independent of the particular rolling configuration—whether strip, plate, bar or rod rolling process. Provided that the system-level constraints are satisfied, and proper geometric alignment is maintained, the same conversion principles can be applied directly to hot rod rolling. In such cases, only the magnitude of the rolling torque and force changes, while the fundamental electromechanical relationships remain unchanged.

The proposed indirect torque-conversion approach eliminates the need for costly load-cell installations and avoids production downtime associated with sensor retrofitting, offering a practical and reliable alternative for real-time roll-force estimation in existing rod mills. Furthermore, the roll force estimated in real time can be directly utilized to optimize key rolling parameters, such as roll-gap settings and roll speed, enabling more stable and adaptive process control.

2. Procedure for Roll Force Estimation Using Motor Current

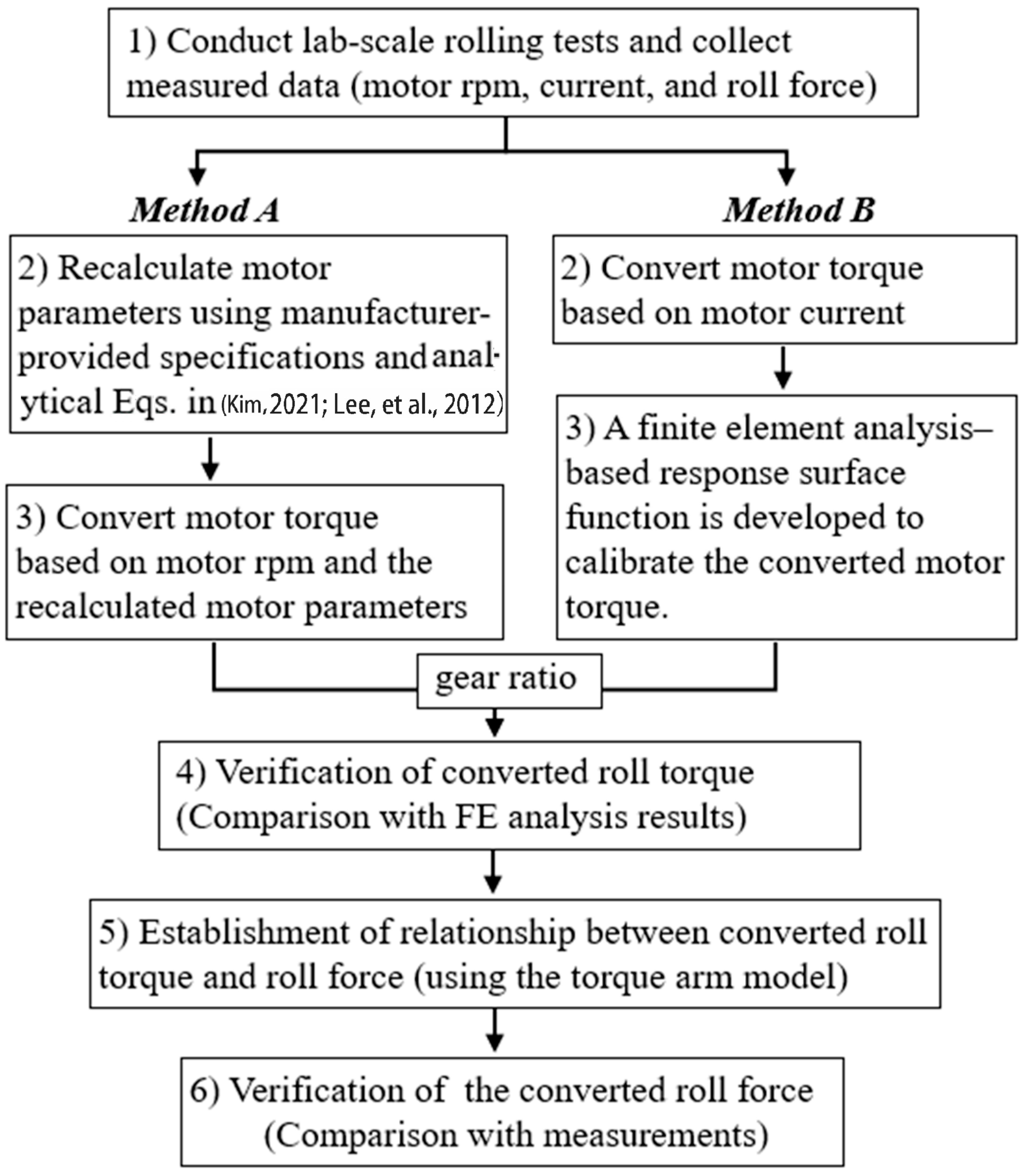

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the proposed roll-force estimation procedure comprises six sequential steps. Laboratory-scale rolling tests are first performed using the fabricated experimental mill to acquire fundamental process data, namely motor rotational speed (rpm), motor current, and roll force. Two approaches—Method A and Method B—are then applied to convert these electrical signals into torque using the equivalent-circuit model of an induction motor.

In Method A, the motor parameters are recalculated from the manufacturer-provided specifications using analytical equations [

15,

16], as the induction motor had been operated frequently for approximately one year. During prolonged operation in the rolling tests, effects such as thermal aging, magnetic saturation, and occasional overloads can alter the electrical characteristics of the motor; therefore, parameter recalibration is required. Using the recalculated parameters, motor torque is obtained via the measured rpm through the equivalent-circuit relations.

In Method B, the motor torque is estimated directly from the measured motor current signals. However, when only current signals are used, subtle variations in slip cannot be captured accurately, which leads to non-negligible errors in the current-to-torque conversion, as also noted in recent studies in the motor current-to-torque conversion [

17]. To compensate for the errors, a finite-element (FE)–based response surface function is constructed. In the FE simulations, torque and roll force are calculated under a range of rolling conditions—specifically, different reduction ratios, specimen widths, and roll diameters—chosen to match the laboratory rolling tests. Based on these results, a response surface function is constructed as a function of reduction ratio and specimen width and used to calibrate the converted motor torque.

For both methods, the converted motor torque is transferred to roll torque through the mechanical gear ratio and then verified by comparison with FE analysis results. The roll force was subsequently calculated using the classical torque–arm relationship. The final verification step, the predicted roll forces are compared with the measured roll-force data.

Either method can be chosen depending on user preference, the available measurement signals, and the capability to perform FE analysis. The proposed indirect torque-conversion framework can also be extended to rolling conditions involving temperature variations and dynamic loading. Because it is based on the electromechanical behavior of the drive system rather than on the specific deformation characteristics of the material, the framework remains applicable under varying thermal and transient load conditions.

3. Experiments

3.1. Laboratory-Scale Pilot Rolling Mill

Figure 2a illustrates the lab. scale rolling mill that was designed and fabricated by the authors’ research team. While the proposed methodology is intended for application in rod or bar rolling, cold strip-rolling tests were performed because the cold strip rolling minimizes measurement errors associated with thermal effects and reduces alignment errors along the longitudinal axis of the specimen, which are common in rod rolling test.

The pilot rolling mill is powered by a three-phase geared induction motor (model F1HM15, Hyosung Heavy Industries, Seoul, Republic of Korea), featuring a gear reduction ratio of 50:1. The motor specifications include a rated voltage of 220/380 V, rated frequency of 60 Hz, 4 poles, and a synchronous speed of 1800 rpm. For compactness and structural efficiency of the pilot rolling mill, the gearbox was mounted directly onto the mill housing. After reduction, the motor delivers an output power of 0.75 kW and a maximum torque of 207 N·m. Motor speed was controlled using an FM3-007LF-NF inverter (Hyosung Heavy Industries, Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Two types of work rolls were used with diameters of 85 mm and 100 mm, and a barrel length of 105 mm. The rolls were designed to withstand a maximum torque of 413.8 N·m and were fabricated from SKD11 tool steel by computer numerical control (CNC) machining (Boo-il Precision Co., Ltd., Siheung-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). All structural components of the mill were fabricated from SS400-grade steel, resulting in a total machine weight of approximately 250 kg, including the rolls and housing. To ensure consistent feeding direction and entry height during experiments, an adjustable entry guide was designed, allowing repositioning to accommodate specimens of different widths.

3.2. Data Acquisition

3.2.1. Motor Current Measurement

A current transformer (CT) was used to measure the current supplied to the induction motor in real time. It was installed such that the motor power cable passed through its center as shown in

Figure 2b. For precise current measurement, the CT was mounted according to the polarity markings on its housing, ensuring the motor-side (L) and breaker-side (K) directions were correctly followed.

The measured current was filtered to remove electrical noise and converted to root mean square (RMS) values before being transmitted to a programmable logic controller (PLC). The RMS value was obtained by sampling the instantaneous current at a fixed rate, squaring each sample, averaging the squared values over the acquisition interval, and then taking the square root of the mean, following .

The PLC was connected to a human-machine interface (HMI), enabling real-time current monitoring both on the current measurement console and PC. In general rolling systems, the PLC issues real-time control commands to actuators while simultaneously monitoring system status and enforcing safety interlocks. In the rolling system employed in this study, however, no control modules or actuators are installed. Consequently, the PLC is dedicated solely to acquiring sensor outputs at a fixed sampling rate, performing initial signal conditioning and timing synchronization, and buffering data to prevent loss during data transmission.

3.2.2. Roll Force Measurement

Rolling forces were measured using two LC8701-T005 load cells (rated capacity: 49 kN each) from AND Co., AND Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea. One load cell is mounted on each side of the upper roll, as shown in

Figure 2b, providing a total load capacity of up to 98 kN. The load cells are connected to an indicator (AD-4321P; AND Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea) and transmitted data to a PC via RS-232C communication.

3.2.3. Roll Rpm Measurement

The roll speed was measured using an AS5048A magnetic encoder. This non-contact absolute angle sensor detects the position of a magnet mounted on the end section of the rotating roll shaft on the operator side, enabling precise measurement of angular position and corresponding roll speed. The measured data are transmitted in real time to a PC (Personal Computer) via a wireless network based on a hybrid SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface)—Ethernet architecture, allowing continuous monitoring and analysis during rolling operations.

3.3. Specimens and Test Conditions

Pure copper (C1100P) [

18] was used as the specimen material. The specimens were prepared in strip form with an initial thickness of 2 mm and a length of 400 mm. Rolling tests were carried out under 12 different conditions, combining two roll diameters (100 mm and 85 mm), different reduction ratios, and two specimen widths (25 mm and 40 mm). To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results, each test condition was repeated three times.

Copper was selected because of practical constraints associated with constructing and operating a laboratory-scale rolling mill. This material choice satisfies several design limitations of the experimental setup, including restricted installation space, the need for easy assembly and disassembly, and the requirement that two students must be able to safely change the rolls. If steel strips were used, the substantially higher rolling loads would require a much larger stand structure, a higher-capacity motor, and increased system stiffness—requirements that exceed what is feasible in a laboratory environment.

All tests were conducted at a constant room temperature (25 °C) under dry conditions, with no additional lubricant applied between the roll and the specimen. To accurately determine the reduction ratio, the specimen thickness was measured before and after rolling using a PMU150-25MX micrometer (Mitutoyo, Japan). The device provides a maximum measurement range of 25 mm and a resolution of 0.001 mm.

Thickness measurements were taken at 13 positions along the longitudinal direction of the specimen at 30 mm intervals. Each measurement point was located at the center along the width of the specimen. This measurement protocol allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of thickness variation along the entire specimen length.

Figure 3 shows the appearance of the specimen after rolling test.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Motor Current Variation

Figure 7 presents the time variation of three-phase induction motor current measured during rolling tests performed under different combinations of roll diameter (100 mm and 85 mm), reduction ratio (9.0–24.8%), and specimen width (25 mm and 40 mm). Each curve represents the transient current response of the motor as the specimen passes through the roll bite. A rapid rise in current is observed immediately after the roll entry, corresponding to the onset of deformation and the sudden increase in rolling load. The current remains nearly constant during steady-state rolling and then drops sharply as the specimen exits the roll gap.

As the reduction ratio increases, the measured motor current increases proportionally, indicating a higher required motor torque. This behavior reflects the greater deformation resistance associated with increased thickness reduction. For a given reduction ratio, larger roll diameters result in slightly higher steady-state current values due to the larger contact arc length and increased frictional contribution to the torque.

A comparison between specimens of different widths (25 mm and 40 mm) shows that both the peak and steady-state current values are higher for the wider specimens. The concurrent increase in motor current can be attributed to the larger roll–material contact area and the greater volume of material deformed per unit time, which requires higher mechanical power input from the motor. These trends collectively demonstrate that the measured motor current reliably reflects the combined effects of roll geometry, reduction ratio, and specimen width on the rolling load, thereby validating its suitability as an indirect indicator of rolling torque and force.

6.2. Converted Roll Torque vs. FE Analysis

As shown in

Figure 8, the roll torque converted from the measured motor current using Method A captures the overall trend of the FE-predicted roll torque, including the initial peak corresponding to material entry into the roll bite and the gradual decrease toward the end of rolling. Hereafter, the term “torque” refers to the roll torque for simplicity. Deviation is defined as the average difference between the FE-predicted torque and the converted torque during the steady-state interval (excluding the initial 1 sec. transient after material entry). The deviation ranges from −11.9% to +28.8% for twelve rolling conditions that are combinations of reduction ratio, roll diameter, and specimen width. However, the converted torque exhibits noticeable time-dependent fluctuations, whereas the FE results remain comparatively smooth. These fluctuations may arise from dynamic effects in the experimental system—such as torsional oscillation of the motor shaft, gear backlash, elastic deformation in the drive train, and transient noise in the measured current. In contrast, the FE analysis assumes quasi-static conditions and idealized contact behavior, excluding such dynamic disturbances. Despite these discrepancies, the average torque levels predicted by the conversion method agree reasonably with the FE predictions.

Figure 9 compares the torque converted from the measured motor current using Method B with the torque predicted by the FE analysis. The deviation between the FE-predicted and measured values was within −7.2% to +13.8% for twelve rolling conditions examined. The converted torque obtained through Method B closely follows the FE-predicted torque in both magnitude and time-dependent response, with only minor deviations near the transient regions of roll entry and exit. Overall, Method B exhibits higher apparent accuracy and smoother temporal behavior than Method A. However, it cannot be conclusively stated that Method B is better than Method A. Although the results of

Figure 9 (Method B) show smoother and more stable behavior than those of

Figure 8 (Method A), the deviations between the FE-predicted and converted torques show no statistically significant difference. Moreover, these results were obtained by applying a surface response function derived from FE analysis of lab-scale rolling mill. Developing such a surface response function is complex and time-consuming, as numerous rolling conditions—such as roll diameter, reduction ratio, and specimen width—must be individually simulated and analyzed.

It should be noted that minor differences in the measured reduction ratios between the two methods arise because the specimen thickness varies slightly even when the roll gap is accurately set. Such small variations are inevitable in laboratory-scale rolling tests due to material inhomogeneity and elastic deformation of the rolls.

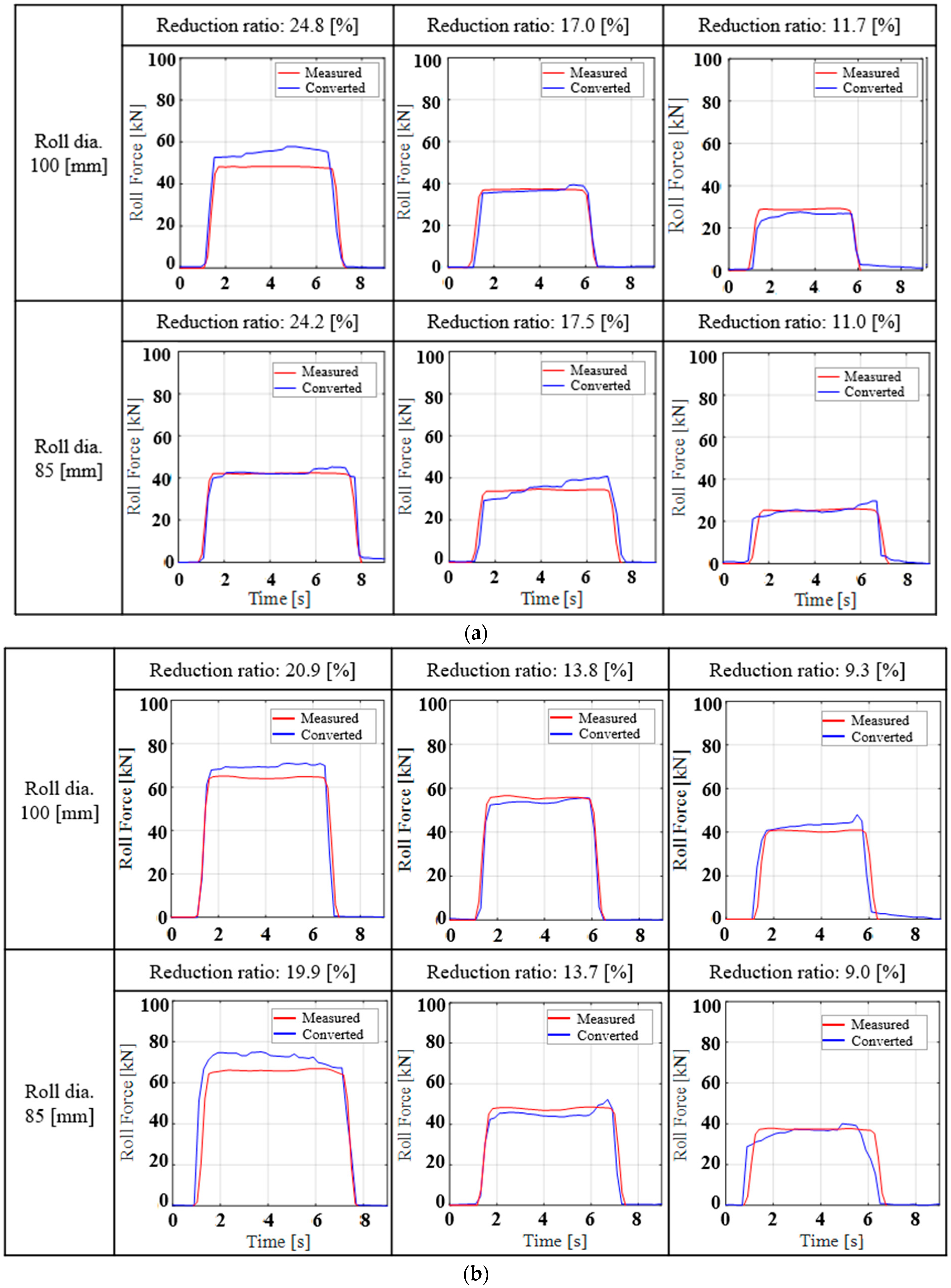

6.3. Converted Roll Force vs. Roll Force Measured by Load Cell

Figure 10 compares the roll force converted from motor torque using Method A with the roll force measured by load cell under various rolling conditions. The converted roll force successfully reproduces the overall trend of the measured data, including the initial rise at roll bite entry and the subsequent drop as the specimen exits the rolls. Across all rolling conditions, the deviation between the converted roll force and experimental measurements remained within −14.1% to +14.9% for twelve rolling conditions. However, noticeable fluctuations are observed in the converted force, particularly during the steady-state region, whereas the measured values remain comparatively smooth. These fluctuations likely arise from mechanical vibration of the rolling stand, elastic deformation of drive components, and transient variations in friction, which are not captured in the simplified torque-to-force conversion model. From a practical perspective, the indirect estimation method proves useful, as the average roll force predicted using the conversion method matches the measured values to a certain degree, without requiring expensive load cells.

Figure 11 compares the roll force converted from motor torque using Method B with the roll force measured by load cell under various rolling conditions. The converted roll forces show overall agreement with the measured data across all combinations of roll diameter, reduction ratio, and specimen width, with deviations ranging from −3.7% to +14.2%. Both data sets show similar temporal evolution—characterized by a sharp rise at roll entry, a stable plateau during steady-state deformation, and small oscillations upon roll exit. Although Method B appears to capture the transient response of the rolling process more accurately, this apparent superiority largely results from calibration using the surface response function obtained from FE analysis of lab-scale rolling mill, which requires a lot of cost and time.

The comparative results obtained from

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 highlight the distinct characteristics of the two torque-conversion schemes. Method A, which estimates slip from the measured rpm, provides a straightforward and computationally efficient means of torque and roll force estimation, even when motor-parameter recalculation—simple in practice—is included. However, torque estimation is more sensitive to transient variations in rotational speed and electrical noise. Hence, the accuracy of Method A largely depends on the precise and stable measurement of the motor’s rotational speed.

Meanwhile, Method B, which determines slip from the motor current, yields smoother and more stable responses but requires calibration of the converted motor torque using an FE-derived surface response function. Developing such a surface response function on the basis of FE analysis is complex and time-consuming, as numerous rolling conditions must be simulated to ensure adequate generality and accuracy.

In summary, Method A provides a simple procedure when reliable roll-rpm data are available, whereas Method B yields smoother temporal responses but requires FE-based calibration and exhibits higher sensitivity to uncertainties in motor parameters.

Table 3 presents a qualitative and quantitative comparison between the two approaches.

Regarding the sources of deviation, several mechanical, sensor-related, and model-related factors contribute to the observed torque and roll-force estimation errors. Dynamic disturbances—including torsional oscillations, gear backlash, and elastic deformation of the drive train—generate high-frequency fluctuations in both rpm and current signals (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). The retrofitted magnetic encoder also exhibits limited precision and high sensitivity to vibration, while the measured current is influenced by inverter harmonics and electrical noise, which propagate directly into the torque-conversion process.

In this context, the limitations and challenges of this work are summarized as follows. First, the laboratory rolling tests were performed under room-temperature, low-load conditions using soft copper, which limits their representativeness for industrial hot rolling conditions. In addition, simplifying assumptions in the FE model of laboratory-scale rolling mill, together with geometry- and reduction-dependent nonlinearities, lead to condition-dependent deviations in the predicted torque and roll force.

7. Concluding Remarks

This study evaluated two indirect torque-conversion methods—an RPM-based approach (Method A) and a current-based approach (Method B)—for estimating roll torque and roll force in a laboratory-scale rolling mill. Method B yielded smoother temporal behavior but required FE-based calibration to compensate for the errors in the current-to-torque conversion. Method A provided a straightforward and transparent conversion path but exhibited a relatively large average deviation from FE-predicted torque and force, compared with Method B.

Experimental results confirmed that both methods successfully reproduced the overall torque and roll force trends during steady-state rolling. Method A demonstrated greater robustness in the recalculated motor parameters, whereas the response-surface function applied in Method B improved agreement with FE predictions, indicating its usefulness in situations where FE simulation of rolling mill are feasible in terms of computational time and cost.

Overall, the proposed framework reliably captured the evolution of roll torque and roll force across a range of geometries and reduction conditions, providing a solid foundation for real-time roll force estimation in rolling mills. Nonetheless, several limitations remain—most notably the use of soft copper strip material, reduced dynamic loading, and room-temperature operation. Measurement accuracy was also influenced by sensor-related factors, including encoder precision and drive-train compliance.

Future work will focus on integrating higher-precision speed-sensing technologies, extending validation to elevated-temperature rolling and more industrially relevant materials, and improving the equivalent circuit model that converts induction motor current into torque.