Development of Electrohydraulic Proportional Valve Model for Precise Steering Control in Autonomous Tractors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agricultural Tractor

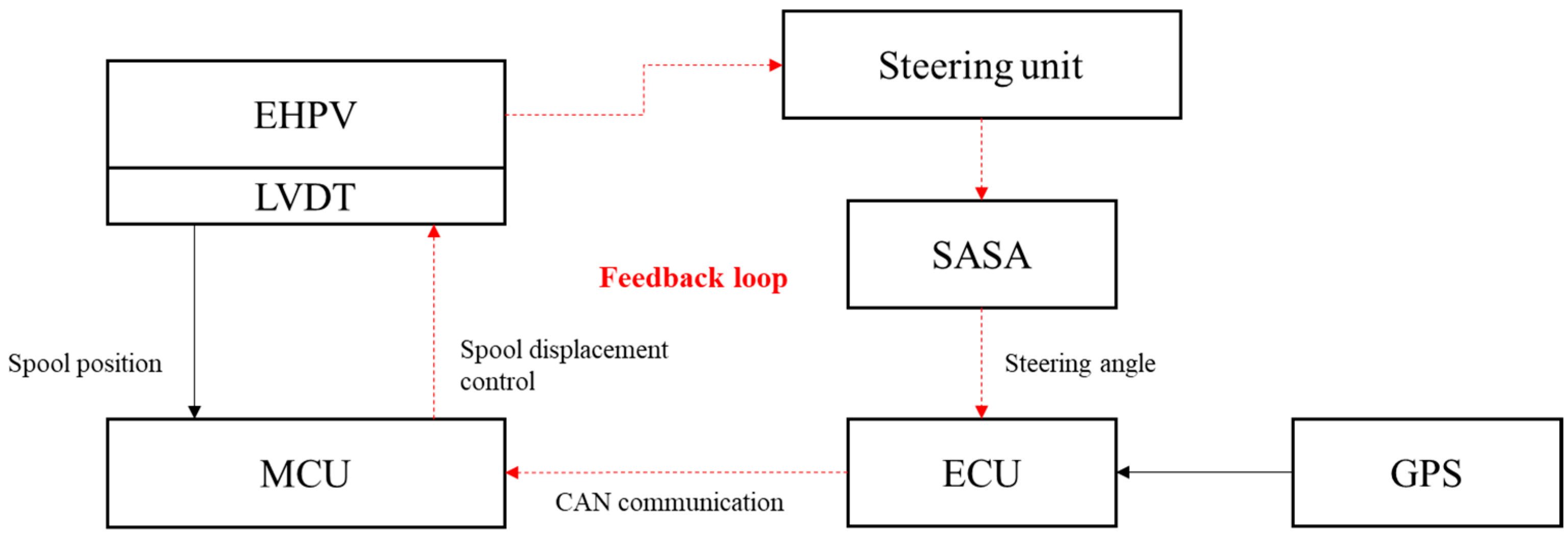

2.2. Hydraulic Steering System

2.3. Measurement System

2.4. Simulation Model

2.5. Test Methods

2.6. Analysis Method

- Steady-state error: This measured the discrepancy between the flow rate of the simulation model once it had stabilized and the value measured under identical conditions.

- Rise time: This was the time required for the flow rate to increase from 10% to 90% of the target flow rate.

- Settling time: This was the duration needed for the flow response to stay within 5% of the target flow rate without deviating.

- Overshoot: This represented the extent to which the peak flow response exceeded the target value, calculated using Equation (2).

- Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE): This represented the absolute error between experimental and simulation values as a percentage of the experimental values, calculated using Equation (3).

- Root mean square error (RMSE): This was the square root of the average squared differences between experimental and simulation values, calculated using Equation (4).

- Normalized RMSE (NRMSE): This was obtained by normalizing the RMSE by dividing it by the mean of the observed values, as calculated using Equation (5).

- Coefficient of determination (R2): This indicated the degree of agreement between the experimental and simulation values, calculated using Equation (6).

3. Results

3.1. Development of the EHPV Simulation Model

3.2. Comparison of Hydraulic Power Characteristics of the EHPV Between Field Tests and Simulation Analysis

3.3. Validation of EHPV Simulation Model

3.3.1. t-Test Results of the Simulation Analysis

3.3.2. Evaluation of Hydraulic Power Prediction Accuracy in the EHPV Simulation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.M. Study on the Utilization of Agricultural Machinery in 2021 and the Survey on the Mechanization Rate of Agricultural Work in 2022; Rural Development Administration: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2022; pp. 16–22.

- The Freedonia Group. Global Agricultural Equipment; The Freedonia Group: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.S.; Anand, R.V. A Review of Energy-Efficient Secured Routing Algorithm for IoT-Enabled Smart Agricultural Systems. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 48, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.T.; Kim, Y.H.; Baek, S.M.; Kim, Y.J. Technology Trend on Autonomous Agricultural Machinery. J. Drive Control 2022, 19, 95–99. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Stentz, A.; Dima, C.; Wellington, C.; Herman, H.; Stager, D. A System for Semi-Autonomous Tractor Operations. Auton. Robot. 2002, 13, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Zhao, L.; Miao, H. Steering Tracking Control Based on Assisted Motor for Agricultural Tractors. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2019, 17, 2556–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Kim, H.J.; Jeon, C.W.; Moon, H.C.; Kim, J.H.; Yi, S.Y. Application of a 3D Tractor-Driving Simulator for Slip Estimation-Based Path-Tracking Control of Auto-Guided Tillage Operation. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 178, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Park, C.H.; Kwon, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, T.S.; Jang, Y.Y. Performance Evaluation of Autonomous Driving Control Algorithm for a Crawler-Type Agricultural Vehicle Based on Low-Cost Multi-Sensor Fusion Positioning. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Jeon, C.W.; Han, X.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.J. Application of Electrohydraulic Proportional Valve for Steering Improvement of an Autonomous Tractor. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 47, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Kim, H.J.; Ha, J.W.; Cho, B.J.; Choi, D.S. An ISOBUS-Networked Electronic Self-Leveling Controller for the Front-End Loader of an Agricultural Tractor. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2017, 33, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Jiang, H. An Electronically Controlled Hydraulic Power Steering System for Heavy Vehicles. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2016, 8, 1687814016679566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmetmuller, W.; Muller, S.; Kugi, A. Mathematical Modeling and Nonlinear Controller Design for a Novel Electrohydraulic Power-Steering System. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2007, 12, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Reid, J.F. Fuzzy Control of Electrohydraulic Steering Systems for Agricultural Vehicles. Trans. ASAE 2001, 44, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tan, J.; Mao, E.; Song, Z.; Zhu, Z. Proportional Directional Valve-Based Automatic Steering System for Tractors. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2016, 17, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Song, Z.; Mao, E.; Zhu, Z. Design and Experiment on Integrated Proportional Control Valve of Automatic Steering System. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.H.; Kim, K.D.; Ahn, D.V.; Park, Y.J. Comparative Analysis of Tractor Ride Vibration According to Suspension System Configuration. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 48, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikwar, S.; Tewari, V.K. Development of Transmission Control Algorithm for Power Shuttle Transmission System for an Agricultural Tractor. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 48, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Raheman, H. Development of a Novel Draft Sensing Device with Lower Hitch Attachments for Tractor-Drawn Implements. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 49, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, D.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Z.; Bai, X.; Mao, Z. Predicting flow status of a flexible rectifier using cognitive computing. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Kobayashi, R.; Nabae, H.; Suzumori, K. Multimodal Strain Sensing System for Shape Recognition of Tensegrity Structures by Combining Traditional Regression and Deep Learning Approaches. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 10050–10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, J.; Shi, G.; Yuan, Q.; Lu, Y. Research on Parameter Identification and Fault Prediction Method of Hydraulic System in Intelligent Sensing Agriculture. Meas. Sens. 2025, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, T.J.; Park, S.U.; Choi, Y.; Choi, I.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, Y.J. Analysis of Power Requirement of 78 kW Class Agricultural Tractor According to the Major Field Operation. Trans. Korean Soc. Mech. Eng. -A 2019, 43, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, L.; Raheman, H. Development of Draft Force Estimation Model for Hand Tractor Powered Digger-Cum-Conveyor by Rake Angle and Digging Depth. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 48, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Gim, D.H.; Jang, M.K.; Hwang, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, Y.J.; Nam, J.S. Development of Regression Model for Predicting the Maximum Static Friction Force of Tractors with a Front-End Loader. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 48, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Specifications | |

|---|---|---|

| Tractor | Dimensions (L × W × H) (mm) | 4670 × 2250 × 2770 |

| Wheelbase (mm) | 2370 | |

| Front track width (mm) | 1680 | |

| Rear track width (mm) | 1790 | |

| Weight (kg) | 4072 | |

| Engine | Number of cylinders | 4 |

| Displacement (cc) | 3409 | |

| Rated power (kW) | 93.2 (@ 2200 rpm) | |

| Front-wheel tire | Section width (mm) | 345 |

| Type | Radial | |

| Rim diameter (mm) | 610 | |

| Overall diameter (mm) | 1184 | |

| Rear-wheel tire | Section width (mm) | 467 |

| Type | Radial | |

| Rim diameter (mm) | 864 | |

| Overall diameter (mm) | 1666 | |

| Steering actuator | Piston diameter of the actuator (mm) | 70 |

| Rods diameter of the actuator (mm) | 35 | |

| Length of stroke (mm) | 274 | |

| Item | Specifications | |

|---|---|---|

| Steering pump | Type | Gear pump |

| Gear ratio of the engine | 1:1 | |

| Displacement (cc/rev) | 21 | |

| Steering oil | Oil tank capacity (L) | 11 |

| Standard | ISO VG 46 | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 860 (at 40 °C) | |

| EHPV | Maximum flow rate (LPM) | 60 |

| Maximum control flow rate (LPM) | 25 | |

| Relief valve pressure (bar) | 210 bar (at 25 LPM) | |

| Temperature range (°C) | −40 to 120 | |

| Item | Specifications | |

|---|---|---|

| Flow meter (Hysense QG100) | Type | Gear type |

| Measurement range (LPM) | 0.7 to 70 | |

| Geometric gear volume (L) | 0.00222 | |

| Resolution (LPM) | 0.133 | |

| Accuracy (%) | ±0.4 | |

| Pressure sensor (Hysense PR130) | Pressure type | Relative pressure |

| Measuring type | Piezo-resistive | |

| Measurement range (bar) | 0 to 250 | |

| Accuracy (%) | ±0.5 | |

| Angle sensor (424A) | Measurement range (°) | 90 |

| Resolution (°) | 0.1 | |

| Accuracy (%) | ±1 | |

| DAQ (Q.brixx A107) | Number of channels | 4 universal input |

| Resolution | 24 bits | |

| Sample rate (kHz) | 10 | |

| Filter | IIR, low pass, high pass, 4th order | |

| Accuracy (%) | 0.01% | |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Fractional spool position function of priority valve | 0.025(x-y) |

| Pilot pressure of priority valve (bar) | 10 |

| Orifice diameter of priority valve (mm) | 1.5 |

| Axial load of the steering actuator mass model (kN/(m/s)) | 64.81 |

| Oil Temperature (°C) | Kinematic Viscosity (cSt) | Absolute Viscosity (cP) |

|---|---|---|

| 40 | 46 | 40 |

| 50 | 28 | 25 |

| 60 | 20 | 17 |

| 80 | 9 | 8 |

| 100 | 5 | 4.5 |

| Engine Speed (rpm) | Flow Rate (LPM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900 | 1400 | 2200 | 2800 | ||

| Spool opening (%) | 25 | 7.22 | 8.60 | 10.74 | 13.68 |

| 50 | 11.70 | 14.25 | 17.30 | 20.79 | |

| 75 | 14.19 | 17.61 | 21.66 | 24.40 | |

| 100 | 15.58 | 19.58 | 24.33 | 27.02 | |

| Engine Speed (rpm) | Oil Temperature (°C) | Control Flow Rate (LPM) | Maximum Flow Rate (LPM) | Spool Opening (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2200 | 40 | 24.33 | 27.59 | 79.26 |

| 50 | 25.05 | 27.91 | 83.60 | |

| 60 | 25.26 | 28.00 | 85.01 | |

| 80 | 25.36 | 28.04 | 85.66 | |

| 100 | 25.36 | 28.04 | 85.66 |

| Engine Speed (rpm) | 900 | 1400 | 2200 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spool Open (%) | 25 | 50 | 75 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 25 | 50 | 75 | |

| Flow rate (LPM) | Steady-state value | 7.22 | 11.7 | 14.2 | 8.7 | 14.5 | 18.1 | 11.3 | 17.8 | 22.5 |

| Max. value | 7.35 | 11.7 | 14.2 | 9.5 | 15.5 | 18.9 | 12.2 | 20.4 | 25.3 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 1.73 | 0.079 | 0.044 | 8.74 | 6.24 | 4.75 | 8.63 | 14.4 | 12.7 | |

| Steady-state error (%) | 0.306 | 0.796 | 1.247 | 0.304 | 0.910 | 1.550 | 0.261 | 1.045 | 1.839 | |

| Settling time (s) | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.57 | |

| Rise time (s) | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |

| Pressure (bar) | Steady-state value | 27.7 | 62.0 | 81.0 | 39.1 | 83.7 | 110 | 58.7 | 109 | 144 |

| Max. value | 28.6 | 62.0 | 81.1 | 46.0 | 93.5 | 119 | 68.7 | 139 | 177 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 3.29 | 0.108 | 0.172 | 17.7 | 11.7 | 8.18 | 17.1 | 28.2 | 23.2 | |

| Steady-state error (%) | 0.652 | 1.084 | 1.717 | 0.568 | 0.874 | 1.373 | 0.569 | 0.675 | 1.047 | |

| Settling time (s) | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.6 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.72 | |

| Rise time (s) | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.19 | |

| Power (W) | Steady-state value | 300 | 1088 | 1726 | 510 | 1827 | 2990 | 992 | 2905 | 4854 |

| Max. value | 315 | 1088 | 1727 | 653 | 2162 | 3373 | 1259 | 4237 | 6675 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 5.04 | 0.029 | 0.047 | 27.9 | 18.4 | 12.8 | 26.9 | 45.9 | 37.5 | |

| Steady-state error (%) | 0.346 | 0.287 | 0.469 | 0.264 | 0.037 | 0.179 | 0.308 | 0.370 | 0.794 | |

| Settling time (s) | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.7 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.74 | |

| Rise time (s) | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.16 | |

| Steering Direction | Steering Angular Speed (rad/s) | Type | Experimental Value (W) | Simulation Value (W) | MAPE * (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine Speed (rpm) | Engine Speed (rpm) | Engine Speed (rpm) | |||||||||

| 900 | 1400 | 2200 | 900 | 1400 | 2200 | 900 | 1400 | 2200 | |||

| Left turn | 0.16 | Max. | 291 | 437 | 678 | 287 | 466 | 674 | 7.89 | 8.49 | 7.45 |

| Avg. | 139 | 199 | 265 | 138 | 203 | 270 | |||||

| 0.21 | Max. | 377 | 575 | 809 | 397 | 605 | 790 | 9.32 | 9.17 | 9.39 | |

| Avg. | 208 | 290 | 345 | 218 | 291 | 335 | |||||

| 0.26 | Max. | 491 | 718 | 1027 | 518 | 720 | 1033 | 9.77 | 9.61 | 9.41 | |

| Avg. | 270 | 349 | 377 | 289 | 339 | 372 | |||||

| Right turn | 0.16 | Max. | 235 | 468 | 648 | 254 | 467 | 682 | 8.99 | 9.87 | 8.56 |

| Avg. | 148 | 168 | 318 | 147 | 171 | 316 | |||||

| 0.21 | Max. | 482 | 671 | 833 | 508 | 707 | 848 | 9.42 | 9.04 | 9.69 | |

| Avg. | 272 | 272 | 381 | 285 | 270 | 380 | |||||

| 0.26 | Max. | 689 | 877 | 1084 | 686 | 887 | 1105 | 9.56 | 9.76 | 9.79 | |

| Avg. | 342 | 336 | 438 | 353 | 328 | 448 | |||||

| Direction | Engine Speed (rpm) | Angular Speed (rad/s) | Experimental Value (W) | Simulation Value (W) | Mann–Whitney U Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. ± Std. | Avg. ± Std. | U-Statistic | Sample Size | p | |||

| Left turn | 900 | 0.16 | 139 ± 91 | 137 ± 92 | 29705 | 245 | 0.845 |

| 0.21 | 208 ± 109 | 218 ± 119 | 36405 | 263 | 0.296 | ||

| 0.26 | 269 ± 143 | 288 ± 144 | 18668 | 186 | 0.187 | ||

| 1400 | 0.16 | 199 ± 134 | 203 ± 143 | 17834 | 188 | 0.878 | |

| 0.21 | 290 ± 164 | 290 ± 177 | 19760 | 199 | 0.972 | ||

| 0.26 | 348 ± 218 | 338 ± 227 | 27843 | 239 | 0.635 | ||

| 2200 | 0.16 | 264 ± 202 | 270 ± 209 | 37858 | 274 | 0.863 | |

| 0.21 | 345 ± 252 | 334 ± 254 | 39052 | 284 | 0.514 | ||

| 0.26 | 376 ± 312 | 372 ± 318 | 39550 | 284 | 0.691 | ||

| Right turn | 900 | 0.16 | 147 ± 66 | 147 ± 74 | 39131 | 277 | 0.684 |

| 0.21 | 271 ± 149 | 284 ± 153 | 46461 | 297 | 0.260 | ||

| 0.26 | 342 ± 207 | 353 ± 219 | 26786 | 228 | 0.573 | ||

| 1400 | 0.16 | 167 ± 151 | 170 ± 152 | 39437 | 280 | 0.902 | |

| 0.21 | 272 ± 210 | 269 ± 212 | 40643 | 286 | 0.898 | ||

| 0.26 | 336 ± 276 | 327 ± 273 | 33790 | 263 | 0.649 | ||

| 2200 | 0.16 | 318 ± 215 | 315 ± 219 | 39385 | 282 | 0.846 | |

| 0.21 | 380 ± 264 | 380 ± 261 | 23693 | 217 | 0.910 | ||

| 0.26 | 437 ± 342 | 447 ± 358 | 34916 | 263 | 0.849 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Baek, S.-Y.; Baek, S.-M.; Kim, W.-S. Development of Electrohydraulic Proportional Valve Model for Precise Steering Control in Autonomous Tractors. Machines 2025, 13, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13020138

Min Y-S, Kim Y-J, Baek S-Y, Baek S-M, Kim W-S. Development of Electrohydraulic Proportional Valve Model for Precise Steering Control in Autonomous Tractors. Machines. 2025; 13(2):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13020138

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Yi-Seo, Yong-Joo Kim, Seung-Yun Baek, Seung-Min Baek, and Wan-Soo Kim. 2025. "Development of Electrohydraulic Proportional Valve Model for Precise Steering Control in Autonomous Tractors" Machines 13, no. 2: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13020138

APA StyleMin, Y.-S., Kim, Y.-J., Baek, S.-Y., Baek, S.-M., & Kim, W.-S. (2025). Development of Electrohydraulic Proportional Valve Model for Precise Steering Control in Autonomous Tractors. Machines, 13(2), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13020138