1. Introduction

The electronic throttle (ET) is a critical actuating component in engine control systems [

1]. It enables closed-loop control of the air–fuel mixture intake by adjusting the rotation angle of the throttle valve plate. In some engine architectures with simplified configurations, the ET may even serve as the sole actuator for comprehensively regulating engine operation. To ensure fast and accurate tracking of reference signals, an ET controller must exhibit not only excellent dynamic response but also strong robustness against intake disturbances. The core of ET control lies in the precise regulation of the drive motor, where input voltage adjustments produce appropriate output torque to rotate the throttle shaft via a reduction gear train. However, nonlinearities and uncertain disturbances—such as gear backlash, nonlinear torque from the return spring, and frictional resistance [

2]—introduce considerable complexity into the system, posing major challenges to high-precision control. In recent years, numerous studies [

3,

4,

5] have been conducted worldwide to address these issues, leading to the development of various control strategies.

Sliding mode (SM) control is a robust nonlinear control strategy that shapes the system behavior by enforcing the state to evolve on a designed sliding surface. Once the sliding motion is established, the closed-loop dynamics become largely insensitive to bounded parameter uncertainties and matched disturbances, while still preserving a fast transient response. For ET systems that are significantly affected by gear backlash, nonlinear spring torque, friction and load disturbances, these properties are particularly desirable, as they help maintain accurate position tracking over a wide range of operating conditions. As a result, it has been extensively applied in ET control [

6,

7,

8]. In addition, various advanced SM control frameworks have been developed for complex nonlinear and switched systems, such as switched controller design for robotic manipulators via neural-network-based sliding mode approaches [

9] and passivity-based adaptive fuzzy SMC for stochastic nonlinear switched systems via T–S fuzzy modeling [

10]. These studies further demonstrate the strong capability of SMC to cope with severe nonlinearities, switching dynamics and stochastic disturbances, which are also encountered, in a different form, in ET systems. However, conventional SM control relies on high-frequency switching via sign functions, which inevitably induces chattering. This phenomenon not only degrades tracking accuracy but also hinders the practical adoption of variable structure control in engineering applications. To mitigate these adverse effects, various methods have been proposed to suppress chattering and improve controller precision. For instance, Wan et al. [

11] developed a novel backstepping sliding mode approach to address inaccuracies in measurements, while Long et al. [

12] incorporated an online zero-crossing detection-based adaptive mechanism into traditional torsion control to enhance ET control accuracy. It is worth noting, however, that these SM control strategies are primarily designed and implemented in the continuous-time domain. In practical applications, control algorithms are usually executed in discrete time. Direct application of continuous-time sliding mode control (SMC) to discrete systems may lead to issues such as reduced accuracy, intensified chattering, discretization errors, and even instability. Therefore, the design and in-depth analysis of discrete-time sliding mode control (DSMC) algorithms that can be directly implemented in digital form constitute a major focus of this study [

13,

14,

15].

In real-world engineering, performance degradation often occurs after discretization due to limitations in sampling frequency. This has prompted extensive research into the behavior of SM control in discrete systems. Gao et al. [

16] introduced the concepts of “quasi-sliding mode” and “discrete reaching law,” noting that discrete reaching may cause the system state to cross the sliding surface alternately, resulting in a zigzagging crossing behavior. Based on this, Bartoszewicz [

17] further refined the quasi-sliding mode and proposed two improved reaching laws that avoid continuous switching and eliminate the need for crossing the sliding surface at every step. The switching nature of SM control makes its digital implementation particularly challenging. The reaching law plays a crucial role in SM control, as it characterizes the motion of the system state near the switching surface and facilitates the analysis and design of dynamics during the reaching phase. Common reaching laws include constant-rate, exponential, and power-rate laws [

18,

19]. Yu et al. [

20] proposed a fast power-rate reaching law that combines exponential and power terms, enabling fast convergence both far from and near the sliding surface. This approach improves overall dynamic performance and significantly suppresses chattering caused by high-frequency switching. These reaching laws are typically discretized using forward difference methods, yielding first-order discrete SM control strategies. However, such simple discretization may fail to fully preserve the dynamic characteristics of the continuous system, leaving challenges in accuracy and stability.

In the field of discrete-time higher-order SM control, various improvements have been proposed to address nonlinearities, uncertainties, and discretization effects. Qu et al. [

21] introduced a discrete reaching law with dynamic disturbance compensation and provided a thorough analysis of system behavior inside and outside the quasi-sliding mode band, enhancing disturbance rejection. Zhang et al. [

22] integrated a hyperbolic tangent function with second-order disturbance compensation to further reduce chattering and improve smoothness and precision. Ma et al. [

23] proposed an adaptive gain mechanism for a discrete fast power-rate reaching law, which adjusts the control gain according to the sliding phase to balance accuracy and response speed, thereby shortening the reaching time. Moreover, Ren et al. [

19] presented a novel discrete sliding mode reaching condition that offers faster convergence compared to conventional methods, facilitating quicker entry into the sliding mode and improving overall performance. These research efforts have collectively advanced the theory and application of discrete-time higher-order sliding mode control. However, from an overall perspective, existing discrete-time higher-order SMC methods still exhibit certain limitations in terms of discretization-related numerical properties and engineering implementation. On the one hand, most approaches are still designed by discretizing continuous-time sliding mode control laws, which makes their performance sensitive to the sampling period and the degree of system nonlinearity. On the other hand, for electronic throttle actuators that exhibit pronounced non-ideal characteristics such as gear backlash, nonlinear spring torque, and friction, there is still a lack of a systematic discrete-time control framework that can simultaneously ensure numerical stability, suppress chattering, and maintain implementation simplicity. It is noteworthy that most discrete reaching laws in the literature are designed based on explicit Euler integration. However, studies have shown that even in the absence of external disturbances or uncertainties, explicit Euler discretization can cause numerical chattering, especially in nonlinear systems [

24]. In contrast, the implicit Euler (backward Euler) discretization method offers greater numerical stability and ensures global asymptotic convergence without altering the control structure, effectively suppressing or even eliminating discretization-induced chattering [

25]. This makes implicit discrete strategies particularly advantageous in digital implementations of SM control.

Inspired by these developments, the implicit Euler method can be incorporated into the design of SM controllers to enhance numerical stability in discrete systems. However, conventional implicit discrete SM controllers often lack a forward recursive structure, leading to high computational complexity and implementation difficulties. To address this, this paper proposes a novel generalized implicit discrete-time fast terminal sliding mode control method (GIDFTSMC). A discrete dynamic model of the ET system is derived using Euler discretization, and a corresponding parameter tuning strategy is provided. Compared to conventional linear SM controllers, the proposed method offers an explicit recursive form, which facilitates practical implementation and improves applicability and adaptability. Experimental comparisons are conducted to demonstrate the advantages of the proposed controller.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

A generalized implicit discrete-time reaching law with an explicit recursive form is developed for electronic throttle systems. By embedding the implicit Euler mechanism into an exponential-type reaching framework and deriving an equivalent algebraically explicit recursion, the proposed reaching law achieves higher sliding mode control accuracy while retaining good numerical stability and implementation simplicity in digital controllers.

- (2)

A recursive discrete fast terminal sliding surface is designed for the third-order discrete ET model. The proposed controller guarantees fast convergence of the closed-loop states after reaching the sliding surface and significantly improves steady-state tracking accuracy, while maintaining a compact structure suitable for real-time implementation on ET actuators.

- (3)

The theoretical properties of the resulting QSM are rigorously analyzed. It is shown that the QSM band exists and that its accuracy achieves second-order precision with respect to the sampling step size. Furthermore, it is proven that, once the system enters the sliding mode, the closed-loop states converge to a neighborhood of the equilibrium point, and an explicit upper bound on the size of this neighborhood is derived.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 derives the discrete dynamic model of the ET system.

Section 3 presents the design and stability analysis of the GIDFTSMC.

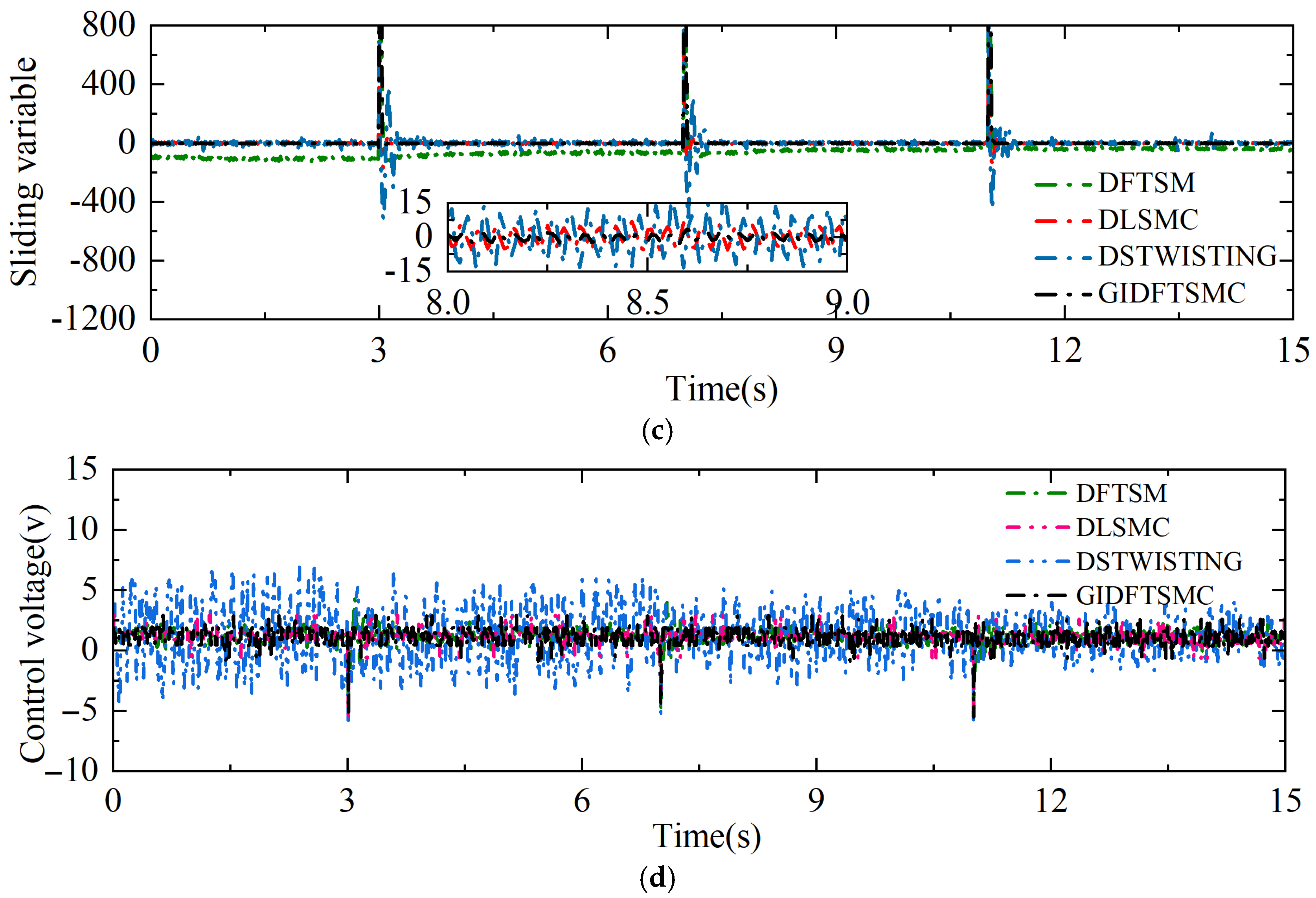

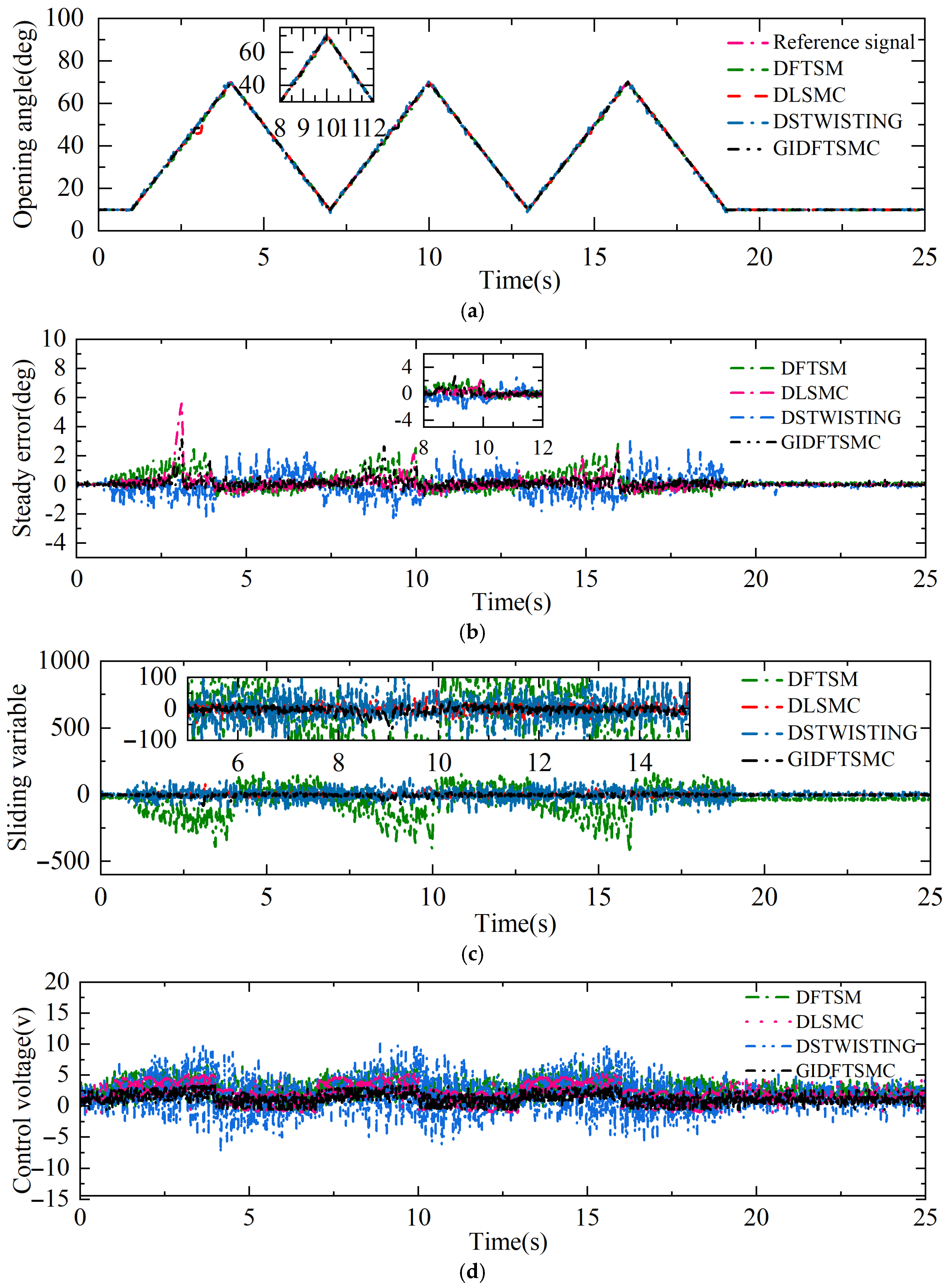

Section 4 and

Section 5 provide comparative numerical simulations and experimental results, respectively, followed by conclusions regarding the control performance.

2. Modeling of the ET System

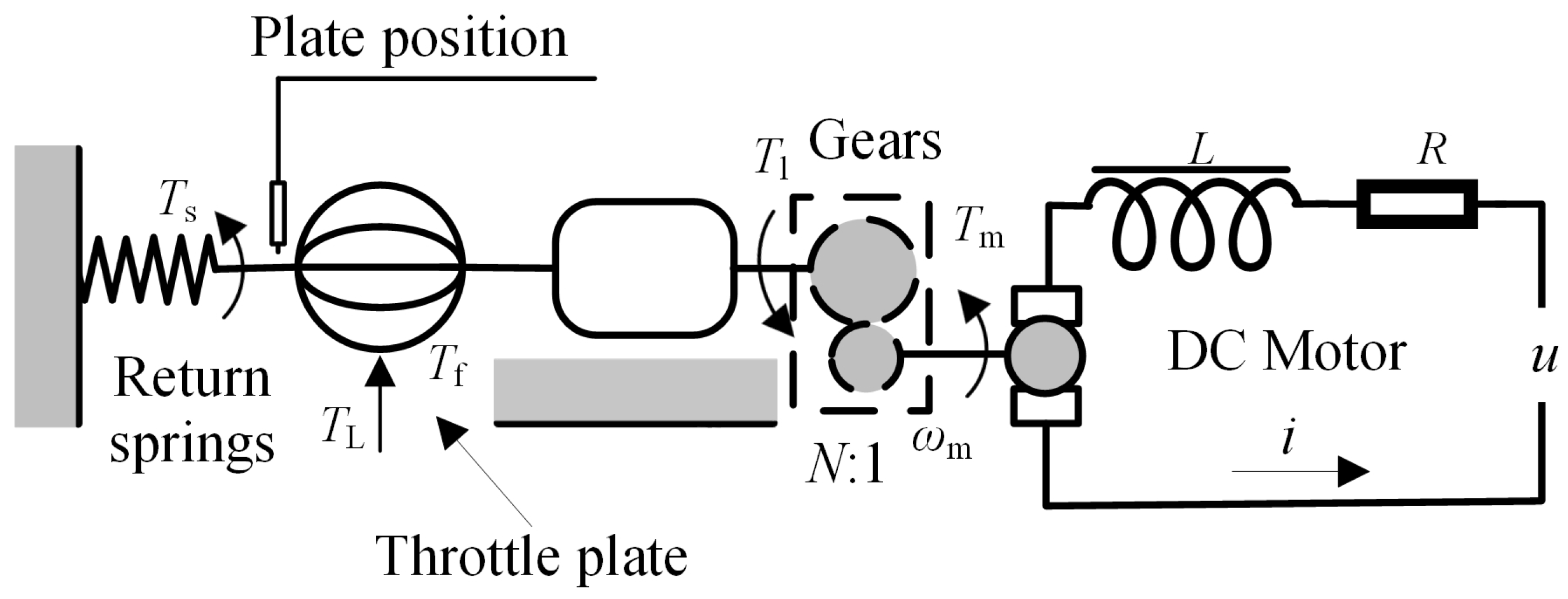

The electronic throttle (ET) system regulates the engine’s air intake precisely by controlling the opening angle of the throttle valve plate. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the system consists of an electrical unit and a mechanical assembly. The electrical unit employs a DC motor as the actuator, providing the necessary driving torque. The mechanical components include a gear reduction mechanism, dual return springs, the throttle valve plate, and a position sensor, which collectively facilitate physical actuation and position feedback. Within the closed-loop control framework, the engine control unit (ECU) generates a desired opening signal as the reference input. This reference value is compared with the actual valve opening, and the controller modulates a pulse width modulation (PWM) signal based on the resulting error to drive the DC motor, thereby achieving dynamic adjustment of the throttle opening. The dynamics of the ET system can be mathematically described as follows [

26]:

where

u denotes the supply voltage when

,

represents the maximum allowable value for safe system operation, and

I is the motor armature current.

R,

ke and

L denote the armature resistance, torque constant, and armature inductance, respectively.

N is the gear ratio, calculated as

.

indicates the output torque of the drive motor.

and

are the angular velocities of the DC motor and the ET plate, respectively.

kt is the motor torque constant.

represents the viscous damping coefficient of the DC motor.

is the moment of inertia of the DC motor.

Based on Newton’s second law, and taking into account the friction torque comprising both Coulomb and viscous friction, as well as the highly nonlinear characteristics of the return spring torque, the equilibrium equations at the valve body, the reduction gear set, the return spring, and the friction torque are established as follows:

where

Jet is the moment of inertia of the valve body.

Tl,

Tf,

Ts and

TL represent the output torque of the reduction gear set, the friction torque, the return spring torque, and the load torque, respectively.

θ denotes the rotation angle of the valve plate, that is, the opening angle of the throttle valve.

kd,

kk,

ks,

km and

θ0 are the viscous damping coefficient, Coulomb friction coefficient, spring stiffness coefficient, spring torque coefficient, and initial valve angle, respectively. By combining Equations (1)–(5), the dynamic equation of the ET system can be derived as:

The system state variables are defined as

and

, representing the valve opening error and the angular velocity error, respectively, expressed as

,

,

where

φ is the reference signal of the opening value. Therefore, the control-oriented model of the ET system can be derived as follows:

where

,

,

,

,

,

, where

d(

t) denotes the lumped disturbance resulting from parametric uncertainties. It is assumed that both the lumped disturbance

d(

t) and its derivative are bounded [

27]:

As can be seen from Equation (8), the lumped disturbance d(t) mainly consists of two parts: the uncertainty of system parameters and external disturbances. The parameter uncertainty involved in Equation (6) stems from the model parameter deviations of the DC motor and the throttle actuator, which can be estimated through modeling and calibration. Since the parameter uncertainty is bounded and the external disturbances fluctuate continuously, the lumped disturbance d(t) and its derivative satisfy and , where and are constants. However, the bounds of the lumped disturbance and its derivative are usually unknown or difficult to measure in practice. Therefore, the ET system has obvious chattering effects and singularity problems.

In view of the fact that control systems in practical engineering applications are generally implemented based on digital computing platforms, the controller needs to operate in the discrete-time domain. Different from the continuous-time SMC approaches, this paper proposes the controller

u design that is implemented digitally, i.e.,

u(

t) =

u (

kh) over the sampling interval [

kh, (

k + 1)

h], where h denotes the sampling time and k ∈ [1, 2, 3…]. In this regard, this paper adopts the explicit Euler method to discretize the equations, thereby obtaining the discrete-time expression of the throttle system [

28]:

where

denotes the sampling step size,

, The expression of

is as follows:

According to the disturbance characteristics matched by the system [

7,

29], the disturbance and its rate of change in the ET system are bounded, that is,

,

where

and

are positive constants. The disturbance term in the discretized ET system satisfies, where

represents the thickness of the boundary layer of

.

The position tracking performance of the ET system directly affects the operational safety, power performance, and fuel economy of the engine. However, during the actual operation of the ET system, the non-linearity caused by the return spring and friction, the intake fluctuations caused by changes in air mass flow, and the torque load are the difficulties in the precise control of the ET system.

3. Design of GIDFTSMC for ET System

3.1. Traditional Discrete-Time Fast Terminal SMC

Discrete-time fast terminal SMC (DFTSMC) consists of two parts: sliding surface selection and discrete-time reach law design. To achieve fast and accurate convergence of the system state to the equilibrium state, the following nonlinear sliding surface is selected:

where

s0 =

x1,

qi <

pi, and

,

,

βi > 0,

,

.

,

. The traditional explicit power reaching law is designed as follows:

where

, through algebraic operations, it is rewritten as

To satisfy the discrete sliding mode reaching condition:

must have:

From Equation (15), the quasi-sliding mode domain of

can be obtained as

Equation (15) indicates that the explicit Euler approximation of the fast power reaching law cannot precisely converge to the sliding mode surface , but can only produce discretization chattering within . By examining Equation (12), the reasons for the numerical chattering phenomenon can be identified as follows: when , occurs, which leads to over-control action within the discrete step size h. The explicit discrete reaching law cannot inherit the favorable characteristics of its continuous counterpart. The convergence speed of the explicit power reaching law heavily depends on the power parameter: when the power parameter is small, the convergence is extremely slow; when it approaches 1, it easily leads to instability. For stiff problems, its numerical stability is poor, requiring extremely small step sizes to maintain convergence, resulting in very low efficiency. In addition, this method is relatively sensitive to initial conditions and has poor fault tolerance. Moreover, it tends to get trapped in local minima or oscillations when dealing with complex nonlinear or high-dimensional problems, exhibiting poor performance.

3.2. Generalized Implicit Discrete Reaching Law

By comparison, the generalized implicit discrete reaching law, through the introduction of implicit structures, weight functions, or delay regulation mechanisms [

30], possesses higher stability and adaptability, and exhibits superior numerical characteristics, especially in handling stiff systems or nonlinear problems. Such methods allow for larger iteration step sizes, improve overall computational efficiency, and can adapt to problem characteristics through parameter adjustment, thereby achieving better performance in terms of approximation speed, precision control, and global convergence. Using the implicit Euler discretization technique, the discrete equivalent form of the fast power reaching law can be obtained as:

It is not difficult to observe from Equation (17) that

and

have the same sign and satisfy

over the entire real number domain. To derive the global convergence and explicit solution of the implicit reaching law, we can further consider:

It can be divided into the following three cases:

Case 1: When , obviously, .

Case 2: When

, Equation (18) can be rewritten as

By solving the quadratic equation, we can obtain

Considering , we can obtain: and . From Equation (17), we can obtain: , therefore, does not exist, only exists.

Case 3: When

, similar to Case 2:

From Equation (17), can be obtained; therefore, only exists.

Combining the above three cases, we can obtain:

Therefore, Equation (23) can actually be regarded as an explicit equivalent form of the implicit reaching law. By explicitizing the implicit structure that originally required iterative solution, it not only retains the numerical stability and strong robustness of the implicit method, but also significantly simplifies the implementation process of the controller. After adopting Equation (23), the control law can be obtained through direct analytical calculation, avoiding the iterative solution steps common in traditional implicit control methods, thereby effectively reducing the dependence on computing resources. In the design of discrete reaching laws, a disturbance compensator is often introduced to improve the robustness of sliding mode control. Considering the disturbance compensation, the reaching law (23) is modified as:

By combining the reaching law (24), the discrete recursive sliding surface (11), and the system state Equation (9), the control law can be obtained as

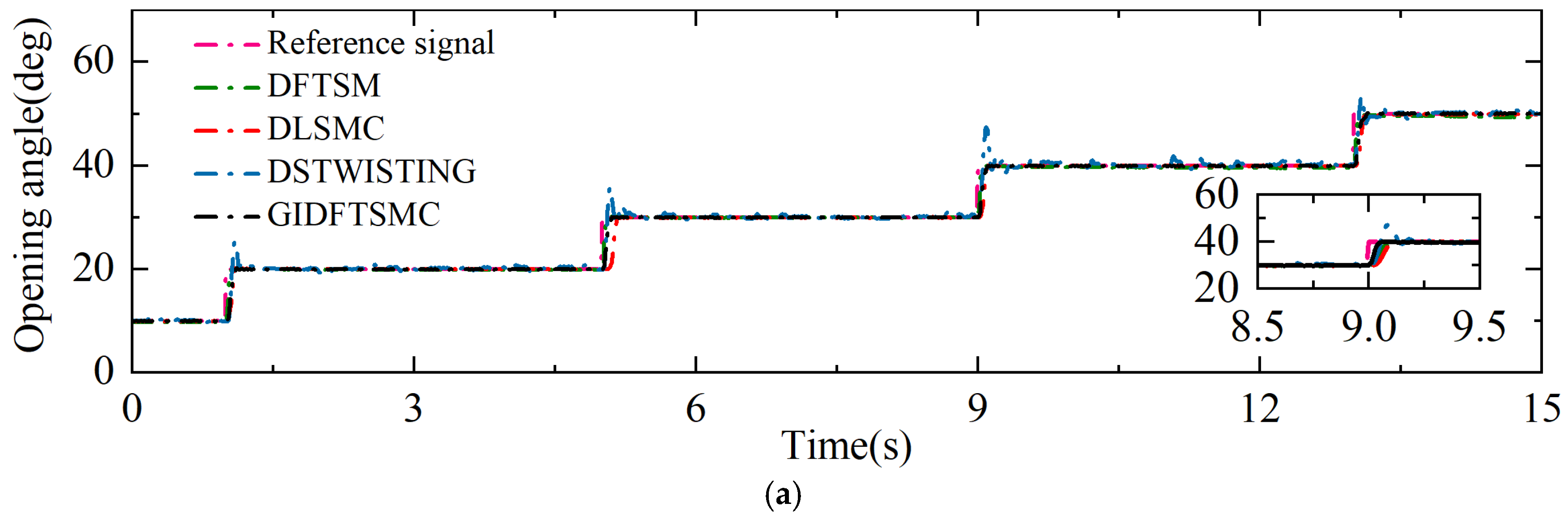

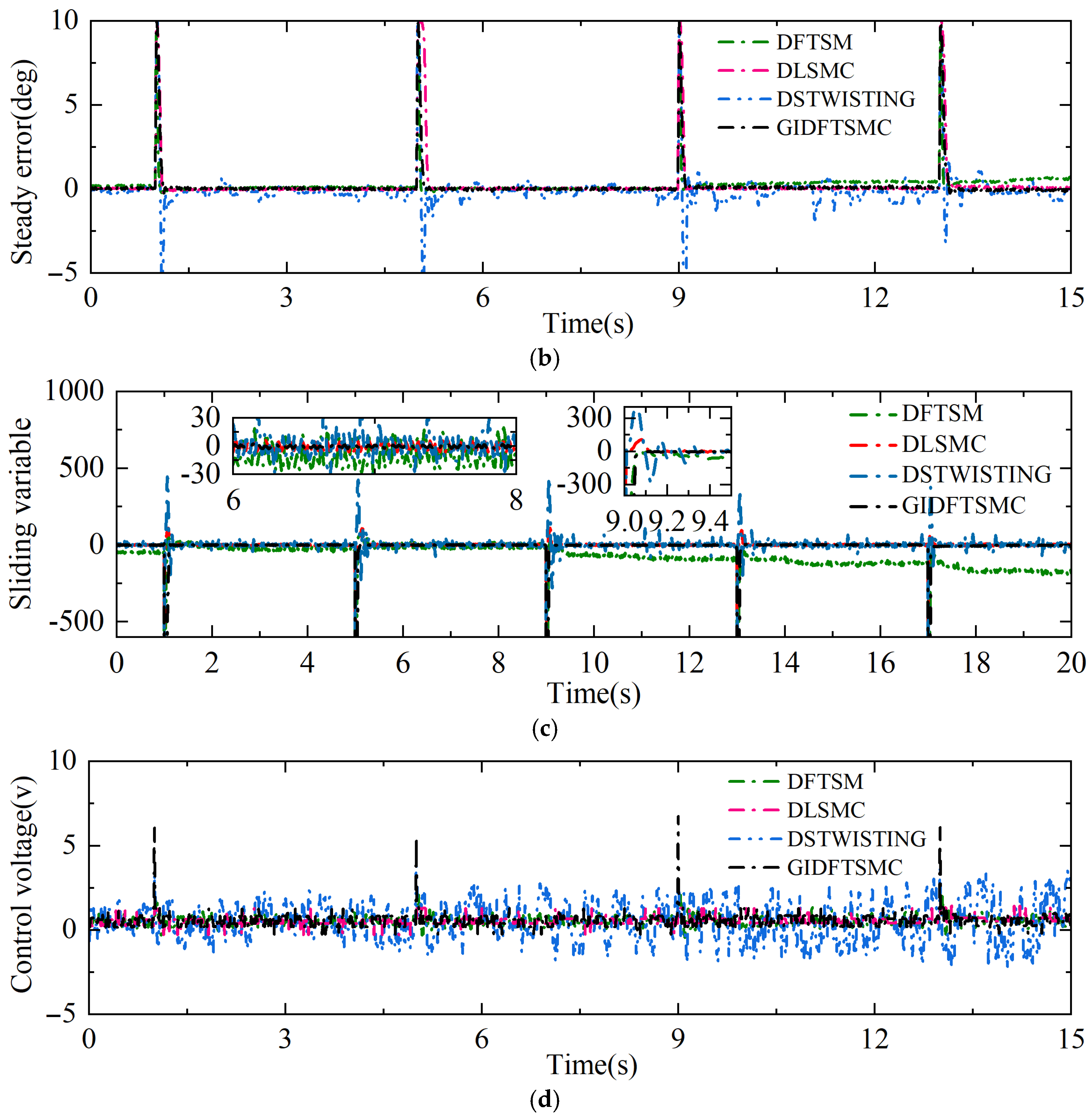

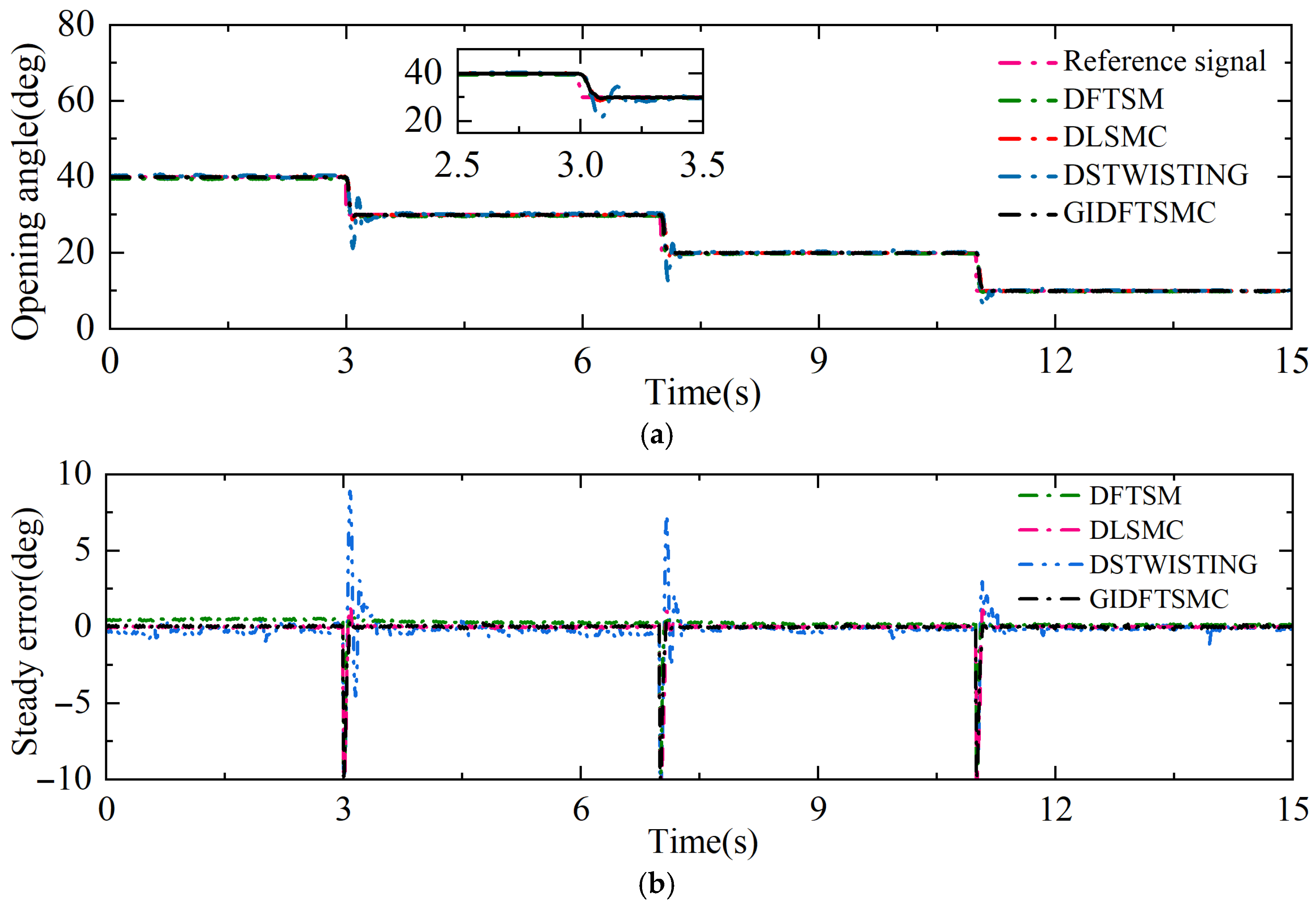

The block diagram of the GIDFTSMC control algorithm is shown in

Figure 2:

3.3. Error Bound and System Dynamics Analysis

Next, this paper will first prove the existence of the Quasi-Sliding Mode (QSM) and evaluate the width of the Quasi-Sliding Mode Domain (QSMD) in the closed-loop system. On this basis, it will further conduct a quantitative analysis of the tracking error of the ET system, so as to theoretically verify the effectiveness and control accuracy of the proposed control strategy.

Theorem 1. For the discrete throttle system (9), under the action of the control laws (11), (24), and (25), if the condition (26) is satisfied and

(definitions see (27)), then the third-order ET system can converge to the QSMD from any initial state. Proof. First, according to the reaching law (17), we can obtain

Consider the following two cases:

Case 1: If

, considering the reaching law (28), the following equation will be obtained:

when

, sampling step size

h >> 1, and from Equation (26), the convergence condition

. Therefore,

exists.

Therefore, it can be solved that when , since the convergence condition (26) is satisfied, . Therefore, , and holds. When , the convergence condition is satisfied.

It can also be observed from Equation (28) that (

k) is monotonically increasing with respect to (

k + 1). Therefore:

Therefore, we can obtain: QSMD is Δa = .

Case 2: Similarly to the above case, omitted.

Therefore, for the proposed GIDFTSMC (Equations (8), (9), (11) and (14)), under the following condition (26), if the sliding variable is outside the QSMD, the ET system will converge to the QSMD from any initial state.

Based on Theorem 1, it is obtained that the system state of the ET system will converge to the vicinity of the sliding manifold, and then, in Theorem 2, the system dynamics of the sliding manifold within the QSMD are analyzed. □

Theorem 2. For the discrete throttle system (9), under the action of the control laws (11), (24), and (25), once the system converges to the QSMD (see (32) for the definition), i.e., The system will not leave this region. If this holds at the finite sampling instant k = k0, then it also holds for any k > k0.

Proof. According to Theorem 1, the system trajectory will converge to the QSMD defined in (32). Next, we will prove that the system will never escape from the QSMD once it enters it. The basic idea of proving Theorem 2 is similar to that in [

27], i.e., to obtain the bound of

and ensure that this bound falls within [−

,

] when

belongs to [−

,

]. The proof considers the two cases based on the positive and negative values of

.

Case 1: .

From the reaching law (23), the convergence process of the sliding variable is as follows:

Taking the first-order derivative of

with respect to

, we can obtain:

Because of

,

is monotonically increasing with respect to

; when

,

satisfies the following boundary.

In summary,

. Next, the question is to determine whether the interval

is contained within

. The following inequality can be derived from the above formula:

Therefore, when , and also belongs to .

Case 2: When , it can be easily proved that under the condition , , and it also belongs to . The detailed proof process is similar to that of Case 1.

Combining the above two cases, the conclusion can be drawn: (32) is indeed valid for any k > k0. In other words, once the state of the ET system enters the QSMD defined in (36), it will never escape from it. □

Remark 1. Considering the relation (32), we can deduce that under the proposed GIDFTSMC, the QSMD has a width of

order, that is,

. Since the proposed controller adopts a two-layer sliding surface structure, the first-layer sliding surface and the system state

will have higher control precision.

Next, we will analyze the error bound of the system tracking error

under the two-layer sliding surface structure. To solve the error bound of the system state

, the following lemmas are needed.

Lemma 1. For the scalar dynamic system

, if , and , then there exists a finite number such that .

Lemma 2. Consider the scalar dynamic systemwhere

, and

is the ratio of odd numbers. If

, then there exists a finite number

such thatwhere the function

is defined as Theorem 3. For the discrete throttle system (9), under the action of the control laws (11), (24), and (25), the closed-loop system will be stable. The sliding surface s1(k) and the system tracking error x1(k) will be uniformly bounded, and the bounds satisfy the following inequality:where K* > 0 is a finite number. Proof. According to the definition of the second-layer sliding surface (11), we can obtain

Then, according to Theorem 2, QSMD satisfies

. Based on Lemma 2, it can be obtained that there exists a parameter

K* > 0 such that

Similarly, according to the definition of the first-layer sliding surface (11), we can obtain

Then, according to (40),

satisfies

. Based on Lemma 1, it can be obtained that there exists a parameter

K* > 0 such that

Obviously, in order to achieve the optimal precision of the tracking error

of the opening valve, appropriate p1 and q1 must be selected such that

Considering (45), we can obtain the range of specific parameters, and then further derive the final bound of for and the final bound of for , respectively. □