Typical = Random

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Some Background on Entropy and Probability

- In statistical mechanics as developed by Boltzmann in 1877 [6], and more generally in what one might call “Boltzmann-style statistical mechanics”, which is based on typicality arguments [29], N is the number of (distinguishable) particles under consideration, and A could be a finite set of single-particle energy levels. More generally, is some property each particle may separately have, such as its location in cell relative to some partitionof the single-particle phase space or configuration space X accessible to each particle. Here and different are disjoint, which fact is expressed by the symbol ⨆ in (5). One might replace ⨆ by ⋃ as long as one knows that the subsets are mutually disjoint (and measurable as appropriate). The microstate is a functionthat specifies which property (among the possibilities in A) each particle has. Thus also spin chains fall under this formalism, where is some internal degree of freedom at site n. In Boltzmann-style arguments it is often assumed that each microstate is equally likely, which corresponds to the probability on defined byfor each . This is the Bernoulli measure on induced by the flat prior on A,for each . More generally, is the Bernoulli measure on induced by some probability distribution p on A; that is, the product measure of N copies of p; some people write . This extends to the idealized case , as follows. For we definewhere means that for some (in words: is a prefix of ). On these basic measurable (and open) sets we define a probability measure byIn particular, if , then its unbiased probability is simply given byIt is important to keep track of p even if it is flat: making no (apparent) assumption (which is often taken to be) is an important assumption! For example, Boltzmann’s famous counting argument [6] really reads as follows [30,31,32,33]. The formulaon Boltzmann’s grave should more precisely be something likewhere I omit the constant k and take to be the relevant argument of the (extensive) Boltzmann entropy (see below). Furthermore, is the probability (“Wahrscheinlichkeit”) of , which Boltzmann, assuming the flat prior (8) on A, took aswhere is the number of microstates whose corresponding empirical measureequals . Here, for any , is the point measure at b, i.e., , the Kronecker delta. The number is only nonzero if , which consists of all probability distributions on A that arise as for some . This, in turn, means that for some , with . In that case,The term in (14) of course equals for any and hence certainly for any for which . For such , for general Bernoulli measures on we havein terms of the Shannon entropy and the Kullback–Leibler distance (or divergence), given byrespectively. These are simply related: for the flat prior (8) we haveIn general, computing from (13) and, again assuming , we obtainfrom which Stirling’s formula (or the technique in [Section 2.1] in [31]) giveswhere is any sequence of probability distributions on A that (weakly) converges to , i.e., the variable in . For the flat prior (8), Equation (20) yieldsAs an aside, note that the Kullback–Leibler distance or relative entropy (19) is defined more generally for probability measures and p on some measure space . As usual, we write iff is absolutely continuous with respect to p, i.e., implies for . In that case, the Radon–Nikodym derivative exists, and one hasIf is not absolutely continuous with respect to p, one puts . The nature of the empirical measure (15) and the Kullback–Leibler distance (19) comes out well in hypothesis testing. In order to test the hypothesis that by an N-fold trial , one accepts iff , for some . This test is optimal in the sense of Hoeffding [Section 3.5] in [31]. But let us return to the main story.The stochastic process whose large fluctuations are described by (22) isThen almost surely, and large fluctuations around this value are described bywhere is open, or more generally, is such that . Less precisely,which implies that if , whereas is exponentially damped if . Note that the rate function defined in (19) and (26) is convex and positive, whereas the entropy (22) is concave and negative. Thus the former is to be minimized, its infimum (even minimum) over being zero at , whereas the latter is to be maximized, its supremum (even maximum) at the same value being zero. The first term in (23) hides the negativity of the Boltzmann entropy (here for a flat prior), but the second term drives it below zero. Positivity of follows from (or actually is) the Gibbs inequality. Equation (26) is a special case of Sanov’s theorem, which works for arbitrary Polish spaces (instead of our finite set A); see [8,31]. Einstein [7] computes the probability of large fluctuations of the energy, rather than of the empirical measure, as Boltzmann did in 1877 [6], but these are closely related.Interpreting A as a set of energy levels, the relevant stochastic process still has and P as in (25), but this time is the average energy, defined byThis makes the relevant entropy (which is the original entropy from Clausius-style thermodynamics!) a function of , interpreted as energy: instead of (26), one obtainswhich “maximal entropy principle” is a special case of Cramér’s theorem [8,31]. If lies in , then . If not, this probability is exponentially small in N. To obtain the classical thermodynamics of non-interacting particles [32], one may add that the free energyis essentially the Fenchel transform [34] of the entropy , in thatFor , the first equality is a refined version of “”.

- In information theory as developed by Shannon [35] (see also [36,37,38]) the “N” in our diagram is the number of letters drawn from an alphabet A by sampling a given probability distribution , the space of all probability distributions on A. So each microstate is a word with N letters. The entropy of p, i.e.,plays a key role in Shannon’s approach. It is the expectation value of the functioninterpreted as the information contained in , relative to p. This interpretation is evident for the flat distribution on an alphabet with letters, in which case for each , which is the minimal number of bits needed to (losslessly) encode a. The general case is covered by the noiseless coding theorem for prefix (or uniquely decodable) codes. A map is a prefix code if it is injective and is never a prefix of for any , that is, there is no such that . A prefix code is uniquely decodable. Let be a prefix code, let be the length of the codeword , with expectationAn optimal code minimizes this. Then:

- Any prefix code satisfies ;

- There exists an optimal prefix code C, which satisfies .

- One has iff for each (if this is possible).

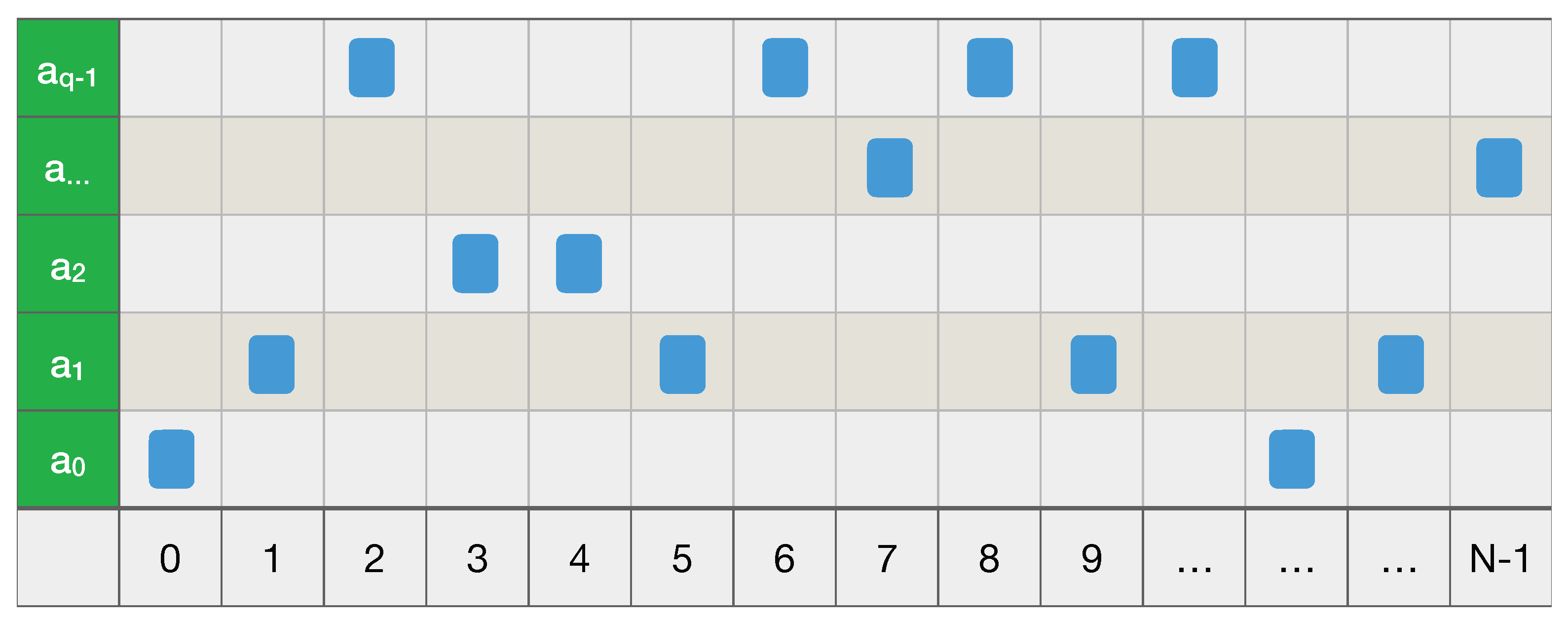

Of course, the equality can only be satisfied if for some integer . Otherwise, one can find a code for which , the smallest integer . See e.g., [Section 5.4] in [36].Thus the information content is approximately the length of the code-word in some optimal coding C. Passing to our case of interest of N-letter words over A, in case of a memoryless source one simply has the Bernoulli measure on , with entropyExtending the letter-code to a word-code by concatenation, i.e., , and replacing , which diverges as , by the average codeword length per symbol , an optimal code C satisfiesIn what follows, the Asymptotic Equipartition Property or AEP will be important. In its (probabilistically) weak form, which is typically used in information theory, this states thatIts strong form, which is the (original) Shannon–McMillan–Breiman theorem, readsEither way, the idea is that for large N, with respect to “most” strings have “almost” the same probability , whilst the others are negligible [lecture 2] in [30]. For with flat prior this yields a tautology: all strings have . See e.g., [Sections 3.1 and 16.8] in [36]. The strong form follows from ergodic theory, cf. (53). - In dynamical systems along the lines of the ubiquitous Kolmogorov [39], one starts with a triple , where X–more precisely , but I usually suppress the -algebra –is a measure space, P is a probability measure on X (more precisely, on ), and is a measurable (but not necessarily invertible) map, required to preserve P in the sense that for any . A measurable coarse-graining (5) defines a mapin terms of which the given triple is coarse-grained by a new triple . Here is the induced probability on , whilst S is the (unilateral) shiftA fine-grained path is coarse-grained to , and truncating the latter at gives . Hence the configuration in Figure 1 states that our particle starts from at , moves to at , etc., and at time finds itself at . In other words, a coarse-grained path tells us exactly that , for (). Note that the shift satisfiesso if were invertible, then nothing would be lost in coarse-graining; using the bilateral shift on instead of the unilateral one in the main text, this is the case for example with the Baker’s map on with and partition , .The point of Kolmogorov’s approach is to refine the partition (5), which I now denote byto a finer partition of X, which consists of all non-empty subsetsIndeed, if we know x, then we know both the (truncated) fine- and coarse-grained pathsBut if we just know that , we cannot construct even the coarse-grained path . To do so, we must know that , for some (provided ). In other words, the unique element of the partition that contains x, bijectively corresponds to a coarse-grained path , and hence we may take to be the probability of the coarse-grained path . This suggests an information functioncf. (34), and, as in (33), an average (=expected) information or entropy functionAs , this (extensive) entropy has an (intensive) limitin terms of which the Kolmogorov–Sinai entropy of our system is defined bywhere the supremum is taken over all finite measurable partitions of X, as above.We say that is ergodic if for every T-invariant set (i.e., ), either or . For later use, I now state three equivalent conditions for ergodicity of ; see e.g., [Section 4.1] in [40]. Namely, is ergodic if and only if for P-almost every x:The empirical measure (15) is a special case of (50). Equation (51) is a special case of Birkhoff’s ergodic theorem; equation (51) is Birkhoff’s theorem assuming ergodicity. In general, the l.h.s. is in and is not constant P-a.e. Each of these is a corollary of the others, e.g., (50) and (51) are basically the same statement, and one obtains (52) from (51) by taking . Note that the apparent logical form of (51) is: ‘for all f and all x’, which suggests that the universal quantifiers can be interchanged, but this is false: the actual logical for is: ‘for all f there exists a set of P-measure zero’, which in general cannot be interchanged (indeed, in standard proofs the measure-zero set explicitly depends on f). Nonetheless, in some cases a measure zero set independent of f can be found, e.g., for compact metric spaces and continuous f, cf. [Theorem 3.2.6] in [40]. Similar f-independence will be true for the computable case reviewed below, which speaks in their favour. Likewise for (52). Equation (51) implies the general Shannon–McMillan–Breiman theorem, which in turn implies the previous one (39) for information theory by taking . Namely:Theorem 1.If is ergodic, then for P-almost every one hasSee e.g., [Theorem 9.3.1] in [40]. Comparing this with (48) and (47), the average value of the information w.r.t. P can be computed from its value at a single point x, as long as this point is “typical”. As in the explanation of the original theorem in information theory, equation (53) implies that all typical paths (with respect to P) have about the same probability .

3. P-Randomness

- 1.

- A topological space X is effective if it has a countable base with a bijectionAn effective probability space is an effective topological space X with a Borel probability measure P, i.e., defined on the open sets .

- 2.

- An open set as in 1. is computable if for some computable function ,Here f may be assumed to be total without loss of generality. In other words,for some c.e. set (where c.e. means computably enumerable, i.e., is the image of a total computable function ).

- 3.

- A sequence of opens is computable iffor some (total) computable function ; that is,for some c.e. . Without loss of generality we may and will assume that the (double) sequence is computable.

- 4.

- A (randomness) test is a computable sequence as in 3. for which for all one hasOne may (and will) also assume without loss of generality that for all n we have

- 5.

- A point is P-random if for any subset of the formwhere is some test (since , such an N is called an effective null set).

- 6.

- A measure P in an effective probability space is upper semi-computable if the setis c.e. (assuming to some computable isomorphisms and ). Also, P is lower semi-computable if the set , defined like (62) with instead of , is c.e. Finally, P is computable if it is upper and lower semi-computable, in which case is called a computable probability space (and similarly for upper and lower computability).

- 1.

- The inequality (64) holds;

- 2.

- (as in Definition 1 (4));

- 3.

- and imply (i.e., extensions of also belong to ).

- 1.

- A string is q-random (for some ) if .

- 2.

- A sequence is Calude random (with respect to ) if there is a constant such that each finite segment is q-random, i.e., such that for all N,

While idealizations are useful and, perhaps, even essential to progress in physics, a sound principle of interpretation would seem to be that no effect can be counted as a genuine physical effect if it disappears when the idealizations are removed. (Earman, [56] (p. 191)).

4. From ‘for P-Almost Every x’ to ‘for All P-Random x’

- 1.

- For -almost every there exists such thatfor all and all , and is the best constant for which this is true.

- 2.

- -almost every is locally Hölder continuous with index .

- 3.

- -almost every is not differentiable at any .

5. Applications to Statistical Mechanics

It is the author’s view that many of the most important questions still remain unanswered in very fundamental and important ways. (Sklar [2] (p. 413)).

What many “chefs” regard as absolutely essential and indispensable, is argued to be insufficient or superfluous by many others. (Uffink [3] (p. 925)).

- 1.

- Coarse-graining (only certain macroscopic quantities behave irreversibly);

- 2.

- Probability (irreversible behaviour is just very likely–or, in infinite systems, almost sure).

- The microstates of the Kac ring model for finite N are pairswith . Here is seen as a spin that can be “up” () or “down” (), whereas denotes the presence () or absence () of a scatterer, located between and . These replace the variables for the Boltzmann equation. In the thermodynamic limit we then have

- The microdynamics replacing the time evolution generated by Newton’s equations with some potential, is now discretized, and is given by mapswhere , with periodic boundary conditions, i.e.,The same formulae define the thermodynamic limit . The idea is that in one time step the spin moves one place to the right and flips iff it hits a scatterer ().

- The macrodynamics, which replaces the solution of the Boltzmann equation, is given byIn particular, for one hasand hence every initial state with reaches the “equilibrium” state , as

6. Applications to Quantum Mechanics

7. Summary

- 1.

- Is it probability or randomness that “comes first”? How are these concepts related?

- 2.

- Could the notion of “typicality” as it is used in Boltzmann-style statistical mechanics [29] be replaced by some precise mathematical form of randomness?

- 3.

- Are “typical” trajectories in “chaotic” dynamical systems (i.e., those with high Kolmogorov–Sinai entropy) random in the same, or some similar sense?

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brush, S.G. The Kind of Motion We Call Heat; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sklar, L. Physics and Chance: Philosophical Issues in the Foundations of Statistical Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Uffink, J. Compendium of the foundations of classical statistical physics. In Handbook of the Philosophy of Science; Butterfield, J., Earman, J., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 2: Philosophy of Physics; Part B; pp. 923–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Uffink, J. Boltzmann’s Work in Statistical Physics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Summer 2022 Edition; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/statphys-Boltzmann/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Von Plato, J. Creating Modern Probability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boltzmann, L. Über die Beziehung dem zweiten Haubtsatze der mechanischen Wärmetheorie und der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung respektive den Sätzen über das Wärmegleichgewicht. Wien. Berichte 1877, 76, 373–435, Reprinted in Boltzmann, L. Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, Hasenöhrl, F., Ed.; Chelsea: London, UK, 1969; Volume II, p. 39. English translation in Sharp, K.; Matschinsky, F., Entropy 2015, 17, 1971–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Zum Gegenwärtigen STAND des Strahlungsproblem. Phys. Z. 1909, 10, 185–193, Reprinted in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein; Stachel, J., et al., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990; Volume 2; Doc.56, pp. 542–550. Available online: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol2-doc/577 (accessed on 15 June 2023); English Translation Supplement. pp. 357–375. Available online: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol2-trans/371 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Ellis, R.S. Entropy, Large Deviations, and Statistical Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.S. An overview of the theory of large deviations and applications to statistical mechanics. Scand. Actuar. J. 1995, 1, 97–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanford, O.E. Entropy and Equilibrium States in Classical Statistical Mechanics; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1973; Volume 20, pp. 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Löf, A. Statistical Mechanics and the Foundations of Thermodynamics; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; Volume 101, pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- McKean, H. Probability: The Classical Limit Theorems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Von Mises, R. Grundlagen der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung. Math. Z. 1919, 5, 52–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mises, R. Wahrscheinlichkeit, Statistik, und Wahrheit, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lambalgen, M. Random Sequences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/23899015/RANDOM_SEQUENCES (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Van Lambalgen, M. Randomness and foundations of probability: Von Mises’ axiomatisation of random sequences. In Statistics, Probability and Game Theory: Papers in Honour of David Blackwell; IMS Lecture Notes–Monograph Series; IMS: Beachwood, OH, USA, 1996; Volume 30, pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.P. Mathematical and Philosophical Perspectives on Algorithmic Randomness. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.cpporter.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/PorterDissertation.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Grundbegriffe de Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Three Approaches to the Quantitative Definition of Information. Probl. Inf. Transm. 1965, 1, 3–11. Available online: http://alexander.shen.free.fr/library/Kolmogorov65_Three-Approaches-to-Information.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Logical Basis for information theory and probability theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1968, 14, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Gács, P.; Gray, R.M. Kolmogorov’s contributions to information theory and algorithmic complexity. Ann. Probab. 1989, 17, 840–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Vitányi, P.M.B. An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.P. Kolmogorov on the role of randomness in probability theory. Math. Struct. Comput. Sci. 2014, 24, e240302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvonkin, A.K.; Levin, L.A. The complexity of finite objects and the development of the concepts of information and randomness by means of the theory of algorithms. Russ. Math. Surv. 1970, 25, 83–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsman, K. Randomness? What randomness? Found. Phys. 2020, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.P. The equivalence of definitions of algorithmic randomness. Philos. Math. 2021, 29, 153–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgii, H.-O. Probabilistic aspects of entropy. In Entropy; Greven, A., Keller, G., Warnecke, G., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grünwald, P.D.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Kolmogorov complexity and Information theory. With an interpretation in terms of questions and answers. J. Logic, Lang. Inf. 2003, 12, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricmont, L. Making Sense of Statistical Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, T. Math 254A: Entropy and Ergodic Theory. 2017. Available online: https://www.math.ucla.edu/~tim/entropycourse.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Dembo, A.; Zeitouni, A. Large Deviations: Techniques and Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dorlas, T.C. Statistical Mechanics: Fundamentals and Model Solutions, 2nd ed.; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.S. The theory of large deviations: From Boltzmann’s 1877 calculation to equilibrium macrostates in 2D turbulence. Physica D 1999, 133, 106–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwein, J.M.; Zhu, Q.J. Techniques of Variational Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lesne, A. Shannon entropy: A rigorous notion at the crossroads between probability, information theory, dynamical systems and statistical physics. Math. Struct. Comput. Sci. 2014, 24, e240311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.J. Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. New metric invariant of transitive dynamical systems and endomorphisms of Lebesgue spaces. Dokl. Russ. Acad. Sci. 1958, 119, 861–864. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, M.; Oliveira, K. Foundations of Ergodic Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier, E.; Lesne, A.; Nikolski, N.K. Kolmogorov’s Heritage in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, P.; Falcioni, M.; Lesne, A.; Vulpiani, A. Chaos and Coarse Graining in Statistical Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Löf, P. The definition of random sequences. Inf. Control 1966, 9, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertling, P.; Weihrauch, K. Random elements in effective topological spaces with measure. Inform. Comput. 2003, 181, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoyrup, M.; Rojas, C. Computability of probability measures and Martin-Löf randomness over metric spaces. Inf. Comput. 2009, 207, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gács, P.; Hoyrup, M.; Rojas, C. Randomness on computable probability spaces—A dynamical point of view. Theory Comput. Syst. 2011, 48, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bienvenu, L.; Gács, P.; Hoyrup, M.; Rojas, C. Algorithmic tests and randomness with respect to a class of measures. Proc. Steklov Inst. Math. 2011, 274, 34–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoyrup, M.; Rute, J. Computable measure theory and algorithmic randomness. In Handbook of Computability and Complexity in Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 227–270. [Google Scholar]

- Calude, C.S. Information and Randomness: An Algorithmic Perspective, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nies, A. Computability and Randomness; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, R.; Hirschfeldt, D.R. Algorithmic Randomness and Complexity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kjos-Hansen, B.; Szabados, T. Kolmogorov complexity and strong approximation of Brownian motion. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2011, 139, 3307–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitin, G.J. A theory of program size formally identical to information theory. J. ACM 1975, 22, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gács, P. Exact expressions for some randomness tests. In Theoretical Computer Science 4th GI Conference; Weihrauch, K., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; Volume 67, pp. 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, L.A. On the notion of a random sequence. Sov. Math.-Dokl. 1973, 14, 1413–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Earman, J. Curie’s Principle and spontaneous symmetry breaking. Int. Stud. Phil. Sci. 2004, 18, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörters, P.; Peres, Y. Brownian Motion; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, P. Convergence of Probability Measures; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Asarin, E.A.; Prokovskii, A.V. Use of the Kolmogorov complexity in analysing control system dynamics. Autom. Remote Control 1986, 47, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fouché, W.L. Arithmetical representations of Brownian motion I. J. Symb. Log. 2000, 65, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouché, W.L. The descriptive complexity of Brownian motion. Adv. Math. 2000, 155, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vovk, V.G. The law of the iterated logarithm for random Kolmogorov, or chaotic, sequences. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 1987, 32, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattka, V.; Miller, J.S.; Nies, A. Randomness and differentiability. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2016, 368, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rute, J. Algorithmic Randomness and Constructive/Computable Measure Theory; Franklin & Porter: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 58–114. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, R.; Griffiths, E.; Laforte, G. On Schnorr and computable randomness, martingales, and machines. Math. Log. Q. 2004, 50, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienvenu, L.; Day, A.R.; Hoyrup, M.; Mezhirov, I.; Shen, A. A constructive version of Birkhoff’s ergodic theorem for Martin-Löf random points. Inf. Comput. 2012, 210, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galatolo, S.; Hoyrup, M.; Rojas, C. Effective symbolic dynamics, random points, statistical behavior, complexity and entropy. Inf. Comput. 2010, 208, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Rojas, C.; Simpson, S. Schnorr randomness and the Lebesgue differentiation theorem. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2014, 142, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- V’yugin, V. Effective convergence in probability and an ergodic theorem for individual random sequences. SIAM Theory Probab. Its Appl. 1997, 42, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towsner, H. Algorithmic Randomness in Ergodic Theory; Franklin & Porter: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- V’yugin, V. Ergodic theorems for algorithmically random points. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.13465. [Google Scholar]

- Brudno, A.A. Entropy and the complexity of the trajectories of a dynamic system. Trans. Mosc. Math. Soc. 1983, 44, 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.S. Algorithmic complexity of points in dynamical systems. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 1993, 15, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterman, R.W.; White, H. Chaos and algorithmic complexity. Found. Phys. 1996, 26, 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.P. Biased Algorithmic Randomness; Franklin and Porter: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 206–231. [Google Scholar]

- Brudno, A.A. The complexity of the trajectories of a dynamical system. Russ. Math. Surv. 1978, 33, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schack, R. Algorithmic information and simplicity in statistical physics. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1997, 36, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouché, W.L. Dynamics of a generic Brownian motion: Recursive aspects. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2008, 394, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Allen, K.; Bienvenu, L.; Slaman, T. On zeros of Martin-Löf random Brownian motion. J. Log. Anal. 2014, 6, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fouché, W.L.; Mukeru, S. On local times of Martin-Löf random Brownian motion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.01877. [Google Scholar]

- Hiura, K.; Sasa, S. Microscopic reversibility and macroscopic irreversibility: From the viewpoint of algorithmic randomness. J. Stat. Phys. 2019, 177, 727–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Weitere Studien über das Wärmegleichgewicht unter Gasmolekülen. Wien. Berichte 1872, 66, 275–370, Reprinted in Boltzmann, L. Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen; Hasenöhrl, F., Ed.; Chelsea: London, UK, 1969; Volume I, p. 23. English translation in Brush, S. The Kinetic Theory of Gases: An Anthology of Classic Papers with Historical Commentary; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2003; pp. 262–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lanford, O.E. Time evolution of large classical systems. In Dynamical Systems, Theory and Applications; Lecture Notes in Theoretical Physics; Moser, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1975; Volume 38, pp. 1–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lanford, O.E. On the derivation of the Boltzmann equation. Astérisque 1976, 40, 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ardourel, V. Irreversibility in the derivation of the Boltzmann equation. Found. Phys. 2017, 47, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, C. A review of mathematical topics in collisional kinetic theory. In Handbook of Mathematical Fluid Dynamics; Friedlander, S., Serre, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 71–306. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, C. (Ir)reversibility and Entropy. In Time Progress in Mathematical Physics; Duplantier, B., Ed.; (Birkhäuser): Basel, Switzerland, 2013; Volume 63, pp. 19–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet, F. Is the Boltzmann equation reversible? A Large Deviation perspective on the irreversibility paradox. J. Stat. Phys. 2020, 181, 515–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodineau, T.; Gallagher, I.; Saint-Raymond, L.; Simonella, S. Statistical dynamics of a hard sphere gas: Fluctuating Boltzmann equation and large deviations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.10403. [Google Scholar]

- Aldous, D.L. Exchangeability and Related Topics; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; Volume 1117, pp. 1–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sznitman, A. Topics in Propagation of Chaos; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; Volume 1464, pp. 164–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kac, N. Probability and Related Topics in Physical Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, C.; Netocny, K.; Shergelashvili, B. A selection of nonequilibrium issues. arXiv 2007, arXiv:math-ph/0701047. [Google Scholar]

- De Bièvre, S.; Parris, P.E. A rigourous demonstration of the validity of Boltzmann’s scenario for the spatial homogenization of a freely expanding gas and the equilibration of the Kac ring. J. Stat. Phys. 2017, 168, 772–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsman, K. Foundations of Quantum Theory: From Classical Concepts to Operator Algebras; Springer Open: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319517766 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Landsman, K. Indeterminism and undecidability. In Undecidability, Uncomputability, and Unpredictability; Aguirre, A., Merali, Z., Sloan, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, S. Bohmian Mechanics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2017. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/qm-bohm/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Landsman, K. Bohmian mechanics is not deterministic. Found. Phys. 2022, 52, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürr, D.; Goldstein, S.; Zanghi, N. Quantum equilibrium and the origin of absolute uncertainty. J. Stat. Phys. 1992, 67, 843–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.Y.; Porter, C.P. (Eds.) Algorithmic Randomness: Progress and Prospects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Landsman, K. Typical = Random. Axioms 2023, 12, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms12080727

Landsman K. Typical = Random. Axioms. 2023; 12(8):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms12080727

Chicago/Turabian StyleLandsman, Klaas. 2023. "Typical = Random" Axioms 12, no. 8: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms12080727

APA StyleLandsman, K. (2023). Typical = Random. Axioms, 12(8), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms12080727