In the context of the one-parameter spatial kinematic

, a stationary line

will generally generate a ruled surface symbolized by

in

. In kinematics, this ruled surface

is a line trajectory. Line trajectories with particular values of velocity and acceleration have many specific distinctions in kinematics. Therefore, given a fixed point

displaced by

where

the velocity and the acceleration vectors of

, respectively, are [

10,

11,

12,

13]:

and

Equation (

27) displays that the stationary lines

that generate ruled surfaces with the same distribution parameter are affiliated with a plane parallel to the

. From Equation (

27), we also have two cases: If

, then

is attendant with the lines in planes passing through the

. If

, the attendant line

of the movable axode generates a developable ruled surface, and Equation (

27) reduces to

Then,

where

is the Darboux vector and

is the dual spherical curvature of

. The dual unit vectors

,

, and

represent alternately orthogonal lines. Their intersection point is the central (striction) point

on the ruling

.

is the joint orthogonal to

and

and is named the central tangent of

at the central point. The locus of the central points is named the striction curve. The line

is the central normal of

at the central point. The tangent vector of striction curve

is

3.1. Inflection Line Congruence

We now examine the line trajectories which are the spatial equivalent of the inflection circle of plane kinematics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It is evident that for all points with

, their loci lie on a dual great circle up to third order. Thus, from Equations (

35), we have:

Therefore, the spatial synonymous of the inflection circle in planar kinematics is situated at (i) the line complex recognized by the inflection cone c: and (ii) the line complex recognized by the associated plane of lines : . All the pencils of lines of the movable space and also in the plane satisfy : , initiating the inflection line congruence. Therefore, the inflection congruence is composed of a pencil of planes, each of which is tied with a direction of the inflection cone c.

Hence, we gain the following theorem:

Theorem 3. Through the movement , consider a pencil of correlating lines of the movable axode, such that each one of these pencils resembles an inflection circle. Then, this pencil of lines forms an inflection line congruence which is the joint lines of the two-line complexes c: and π:

Furthermore, from Equations (

31) and (

34), we can also see that

In this instant, the lines

,

, and

form the Blaschke frame and they are intersected at the striction point of the ruled surface

. From Equations (

31) and (

37), it may be shown that the striction curve of

will have a tangent orthogonal to its ruling; that is,

. In this case, (

) is a binormal ruled surface. Furthermore, if we use

in Equation (

30), we have

. The curve that satisfies this ODE is a great dual circle on

. For example, a great dual circle can be designated as

. The tangent vector can be defined as

. Thus,

has the form

. Let

be a point on

, then

A relationship such as

,

reduces the inflection line congruence to an inflection ruled surface. Thus, we set

, with

h indicating the pitch of

. Then, by excluding

u and

t, we attain

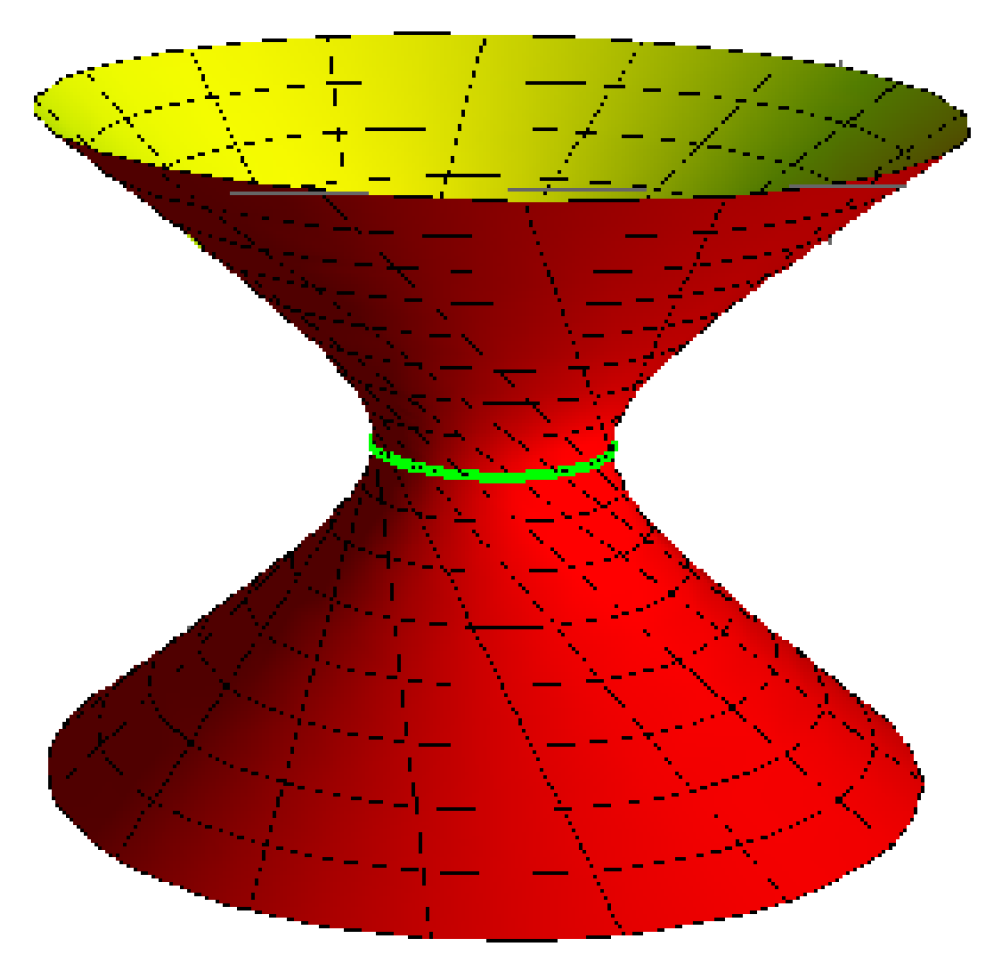

which is a one-parameter family of helicoidal surfaces. If we set

,

, and

, then an element of such a family can be attained (

Figure 1).

Theorem 4. In the Euclidean 3-space , any right helicoidal surface belongs to inflection line congruence.

3.2. Procedure for Locating a Line Congruence

In this subsection, we offer a procedure for locating a line congruence from the coordinates of

. Then, as a special case, we will induce the procedure for the inflection line congruence. From Equation (

20), we have that

is an orthogonal dual vector to both

and

; that is,

Then, the set {

} constitutes a hyperbolic line congruence whose focus line is the line

. We place

with respect to

by its restrict distance

, metrical through the

and the angle

metrical with respect to

. We insert the dual angles

and

, which display the locations of

and

along

(see

Figure 2). Then,

From Equations (

29) and (

39), we attain

Similarly, we have

where

. Notably,

is the origin of the relative Blaschke frame, that is,

, see

Figure 2. This indicates that

and

are real constants. Via the real and the dual parts of

in Equation (

39), we attain:

Let

a be a point on

. Since

a, we have a system of linear equations in

(i = 1, 2, 3, and

are the coordinates of

a):

The matrix of coefficients of unknowns,

, is the skew symmetric matrix

and thus its rank is 2 with

(

k is an integer). The rank of the augmented matrix

is also 2. Then, this system has infinite solutions specified by

Since

can be arbitrary, then we may take

. In this case, we have

which is the base surface of the line congruence. Let

be a point on the directed line

, then

where

. Since

and

are two independent variables, we can say that (

), in general, is a line congruence in the

space. If we take

and

as the movement parameter, then

is ruled in the

space. As a result, the base surface reduces to the striction curve on (

), that is,

The curvature

and torsion

can be assigned by

Then,

is a cylindrical helix along the

, and the ruled surface is

The constants

h,

, and

can control the situation of the surface

. In the case where

and

, we attain:

where

and

. Thus,

is a two-parameter hyperboloid of one sheet. The intersection of each hyperboloid and the plane

is a one-parameter family of cylinders

:

, which is the envelope of

. Furthermore, the ruled surface

can be separated as follows:

- (1)

An Archimedes helicoid, where its striction curve is a cylindrical helix, for

,

,

, and

(

Figure 3).

- (2)

A hyperboloid of one sheet, where its striction curve is a circle, for

,

,

, and

(

Figure 4).

- (3)

A right helicoid, where its striction curve is a line, for

,

,

,

, and

(

Figure 5).

- (4)

A cone, where its striction curve is a stationary point, for

,

,

, and

(

Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Archimedes helicoid.

Figure 3.

Archimedes helicoid.

Figure 4.

A hyperboloid of one sheet.

Figure 4.

A hyperboloid of one sheet.

Figure 5.

A right helicoid.

Figure 5.

A right helicoid.

Explanations of the Inflection Line Congruence

For the kinematic differential geometry of the inflection line congruence, from Equation (

31), we have

Equation (

46) is the dual inflection point trajectory in spherical kinematics (compared with [

1,

2,

3]). This spherical recognition is a dual spherical curve of the third degree. The real part of Equation (

46) displays the inflection cone as

The meeting of the inflection cone with a real unit sphere fixed at the peak of the cone demonstrates a spherical curve. The dual part of Equation (

42) demonstrates the linked plane of lines:

Furthermore, if we substitute Equation (

46) into Equations (

47) and (

48), respectively, we attain

and

If Equation (

49) is solved with respect to

, we gain

From Equations (

51) and (

50), we find

Equation (

52) is linear in the coordinates

and

of

. Thus, for a one-parameter spatial movement

, the lines in a given stationary direction in the

space lie on a plane. As shown in

Figure 7, the angle

identifies the central normal

; thus, Equation (

52) defines two lines

and

in the plane spanned by

and the

(

and

are conformable to the inflection circle in planar kinematics). If the distance

over the

is taken as the independent parameter, then Equation (

52) becomes

where

. Equation (

53) displays that the two lines

and

intersect the

at a distance of

. for

these lines are through

, and their achieve their minimum slope

. Furthermore,

(or

will change its place if

is realized as a varying value and

is a constant. Furthermore, the place of the plane

changes if the variable

of

(or

has several values and

is a constant. Therefore, the set of all lines

and

realized by Equation (

53) is an inflection line congruence for all values of

(

Figure 7).

Now, it is simple to explain a parametric equation of the ruled surface in the inflection line congruence. For this objective, from the real part of Equation (

39) and from Equation (

51), we obtain

which is the inflection curve of the spherical part of the movement

. From Equations (

44) and (

51), we attain

where

h,

, and

can control the shape of the surface

. Furthermore, for example, from Equations (

54) and (

55), we have:

- (1)

An inflection curve and a ruled surface with a striction curve for

,

,

, and

(

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

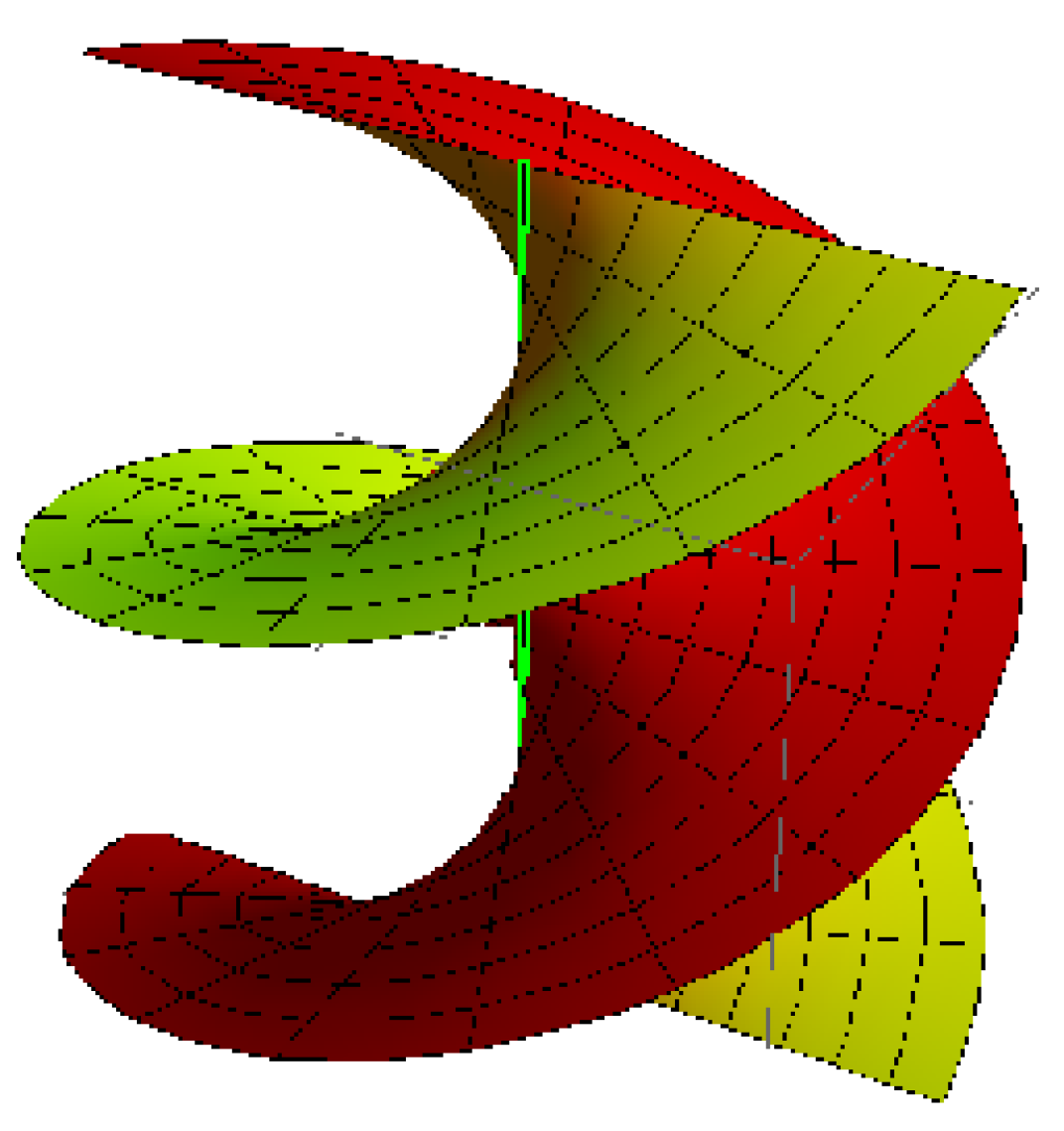

- (2)

An inflection curve and a ruled surface with a striction curve for

,

,

, and

(

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

Figure 8.

Inflection curve.

Figure 8.

Inflection curve.

Figure 10.

Inflection curve.

Figure 10.

Inflection curve.

Figure 11.

Ruled surface.

Figure 11.

Ruled surface.

3.3. Euler–Savary Equation and Disteli Formulae

In 1914, Disteli [

9] succeeded in locating a curvature axis for the generating line of a ruled surface and established the Euler–Savary equation in spatial kinematics. The Disteli formulae may be gained

directly by calculating the dual spherical curvature of

as follows. The dual spherical radius of curvature

can be written as (see

Figure 2):

Then, we have the identity

From substituting Equations (

34) and (

39) into Equation (

57), we acquire

After some algebraic manipulations, this becomes

Equation (

58) is a dual spherical Euler–Savary equation (compared with [

1,

2,

3]). Via the real and the dual parts, respectively, we get

and

Equations (

59) and (

60) are new Disteli formulae in a one-parameter spatial movement; the first one reveals the relationship between the places of the stationary line

in the movable space

and the Disteli axis

. The second one identifies the distance from the line

to the Disteli axis

.

At the end of this section, we derive a dual Euler–Savary formula for the axodes as follows. Substituting

,

,

, and

into Equation (

58), we find, after simple simplifications, that

This is a dual form of a well-known Euler–Savary formula from ordinary spherical kinematics [

1,

2,

3].

This dual version identifies an association between the two axodes in immediate contact and the kinematic geometry corresponding to the instantaneous invariants of the movement

. From separating the real and the dual parts, respectively, we find

and

Equation (

61) together with Equation (

62) are novel Disteli formulae for the axodes of the movement

.