1. Introduction

Badlands are among the most distinctive erosional landforms globally, forming under conditions of high relief energy, limited vegetation, and easily erodible materials. They occur in various climatic and tectonic contexts, including for example the American Great Plains, the Chinese Loess Plateau and the Mediterranean basin [

1,

2,

3]. Despite regional differences, badlands share a common set of geomorphic processes like intense gullying, piping and mass wasting, which make them sensitive indicators of land degradation and environmental change.

In the Mediterranean region, badlands are particularly widespread due to the interplay between marine clays, steep relief, and seasonally concentrated rainfall [

3]. In Italy, they are known as calanchi and biancane, and have long served as natural laboratories for studying slope instability, gully dynamics, and erosion rates [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Given their miniature fluvial system geometry, badlands are often considered ideal natural laboratories for studying landscape evolution [

8]. Erosional processes include linear forms (gullies, rills, piping) and areal forms (slides, flows, sheet erosion) [

9]. Morphometric analyses can quantify the relationships between badland erosion and parameters such as shape, area, drainage frequency, drainage density, slope, and relief [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In fact, the badlands drainage basin shape properties affect the way in which surface runoff is formed and moves within the drainage area, through hillslopes and channel networks [

8,

15,

16,

17]. Traditional morphometric analyses for highly dissected terrain often depend on local slope, curvature, and flow accumulation fields derived from very high-resolution DEMs and their reliability rapidly degrades when DEM resolution or quality are insufficient. In addition, automated extraction of drainage networks in badlands is frequently affected by DEM noise, artifacts, and difficulties in representing very narrow gullies, which may lead to inconsistent estimates of drainage density and related indices. However, many of these morphometric indices rely on laborious analytical procedures and high-resolution digital elevation models, a requirement that limits their applicability in small, highly dissected basins such as those found in badland environments.

To overcome this limitation, this study introduces the Badland Dissection Index (BDI), a new morphometric parameter designed to express the degree of internal dissection and drainage maturity of badland basins. This index is extremely simple to calculate and can be applied worldwide, as it only requires the mapping of the main channel (LMs) and of the total channelized network (LTs), which can be derived from a combination of medium-resolution DEMs and orthophoto-based manual digitization. As a consequence, BDI is less sensitive to sub-cell noise and to the exact resolution of the DEM than indices that depend on pixel-scale slope and curvature fields. The BDI links channel organization with geomorphic evolution, allowing for a clearer understanding of how fluvial and mass-wasting processes interact during different stages of landscape development.

The main objectives of this work are to:

- –

quantitatively describe the morphometric attributes of 87 calanchi basins in the Basilicata region of southern Italy;

- –

evaluate the geomorphic meaning and potential universality of the BDI;

- –

interpret the relationships between basin shape, relief, and drainage characteristics to infer the evolutionary stages of badland development.

Through this approach, we aim to provide a methodological and conceptual framework that can be applied to badland environments in other semiarid regions worldwide.

2. Study Area

The research area is located in the Ionian Basilicata (southern Italy), within the Fossa Bradanica depression between the middle Basento River and the Salandrella–Cavone basins (

Figure 1). The investigated surface covers about 35.7 km

2, of which approximately 3.0 km

2 are affected by active calanchi and biancane. This sector is emblematic of the Apennine foredeep, where Quaternary uplift and denudation have exposed thick sequences of Pleistocene Subappennine Clays [

18].

The area exhibits a monoclinal structural arrangement with strata dipping gently to the northeast [

19]. The geological succession includes a lower unit of blue-gray clays overlain unconformably by sandy-gravelly regressive deposits forming marine terraces. The caprock promotes slope steepening and instability, while the underlying clays are prone to piping and shallow landsliding.

Two main morphological zones are identified [

18,

19]:

High-energy reliefs (HER): compound scarps with steep slopes (>25°) formed by sandy-conglomeratic caprock over plastic clays. These slopes are dominated by rotational slides, debris flows, and fluvial incision, leading to the exclusive development of calanchi;

Low-energy reliefs (LER): gentler slopes (5–25°) characterized by homogeneous clay lithology locally capped by sands, where surface runoff, rainsplash, and piping dominate, giving rise to mixed calanchi–biancane morphologies.

The area has a Mediterranean semiarid climate, with mean annual rainfall of 550–650 mm, mostly concentrated in autumn and winter, and mean annual temperature around 16 °C [

20]. In recent years, the area has experienced an increase in moderately extreme to extreme events (hourly rainfall exceeding the 95th and 99th percentiles, and the number of hourly rainfall events greater than 10 mm), particularly during summer and autumn [

21,

22].

3. Materials and Methods

This study integrates field observations, aerial photo interpretation, and GIS-based morphometric analysis. Aerial orthophotos from the Basilicata Regional Cartographic Database (Regione Basilicata, Potenza, Italy, 2020) and a 1 m-resolution numerical topographic base (CTR 1:1000, Regione Basilicata, Potenza, Italy) were used to delineate drainage networks and basin boundaries. The 1 m-resolution digital elevation model provided the basis for slope and relief analyses.

All data were processed in ArcGIS 10.5 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). For each of the 87 selected calanchi basins (vegetation-free, south-facing, and within homogeneous lithology and climate), the following parameters were extracted:

- –

Badland basin perimeter (P);

- –

Total badland basin area (A);

- –

Length of the badlands basin (Lb);

- –

Length of the main badland channel (LMs);

- –

Total length of badland channels (LTs);

- –

Drainage density (DD);

- –

Relief ratio (RR);

- –

Slope (S);

- –

Topographic wetness index (TWI) [

23];

- –

Stream power index (SPI) [

24];

- –

Hypsometric integral (HI) [

25,

26].

Since the degree of evolution of a badland basin depends on the extent of cross-dissection of its drainage network, this paper introduces a new index called the Badland Dissection Index (BDI), defined as the ratio of the length of the main stream (LMs) to the total length of all streams within the badland basin (LTs):

Badland channels were identified through a combination of high-resolution DEM analysis and orthophoto interpretation. Flow direction and flow accumulation were derived from the 1 m-resolution DEM, and preliminary channel networks were extracted using accumulation thresholds calibrated on field observations. These networks were then manually refined using 2020 orthophotos to exclude ephemeral rills and include only well-defined, incised channels representative of active erosion (

Figure 2).

Although the BDI is derived from DEM-based drainage networks, it does not rely on local terrain derivatives such as slope, curvature, or pixel-scale contributing area, which are highly sensitive to DEM resolution and noise. Instead, the index is based on spatially aggregated properties of the drainage network at basin scale, namely the relative organization of main and secondary channels. As a result, while BDI is not independent of DEM quality, it is less sensitive to resolution effects than many traditional morphometric indices and can be reliably applied using medium-resolution topographic data.

The advantage of this index is that its values range from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates the presence of a single watercourse (

Figure 2). Very high values (>0.7) reflect a juvenile stage in the evolution of the badland basin, characterized by a poorly developed gully network. Conversely, very low values (<0.3) indicate a highly mature stage, with strong cross-dissection and numerous furrows. We can reasonably exclude that high BDI values correspond to senescent stages, since the steep slopes of the reliefs ensure a continuous rejuvenation of these basins.

The BDI offers several practical advantages. It is extremely simple to compute, requires only the total length of the channelized badland network, and can be applied even in areas lacking high-resolution topographic data. In addition, it is sensitive to geomorphic processes driving dissection and can be used for spatial comparisons, temporal analyses, and erosion monitoring at different scales.

To complement the analysis, the most common morphometric indices used in basin shape studies were considered [

27], namely:

- –

Circularity ratio (CR);

- –

Elongation ratio (ER);

- –

Form factor (FF);

- –

Melton ratio (MI);

- –

Gravelius compactness index (GCI);

- –

Constant of channel maintenance (CCM);

- –

Lemniscate index (K).

Circularity ratio (CR) [

28] is defined as the ratio of the basin area (A) to the area of a circle with the same perimeter (P). This parameter is critical in assessing the maturity of the basin. Low values (CR < 0.3) indicate a young stage, medium values (0.3 < CR < 0.7) a mature stage, and high values (CR > 0.7) an old stage in the geomorphic cycle. Circular basins, where the distance from the boundary to the center is relatively uniform, typically exhibit shorter and more uniform response times for runoff to reach peak discharge [

29].

Elongation ratio (ER) is defined as the ratio between the diameter of a circle of the same area as the basin and the maximum basin length. Values close to 1 indicate circular basins and low relief, while values below 0.8 suggest greater relief and steeper slopes. Re values can be classified as circular (>0.9), oval (0.9–0.8), less elongated (0.8–0.7), and elongated (<0.7) [

30].

Form factor (FF) represents basin shape, calculated as the ratio of basin area to the square of its length [

31]. Values range from 0 (very elongated) to 1 (square-shaped). Lower values indicate elongated basins with lower peak flows and longer runoff durations [

17].

Melton ratio (MI) is the ratio of basin relief to the square root of basin area [

32]. It is used to distinguish between basins prone to flooding (MI < 0.3) and those where debris flows predominate (MI > 0.6) [

33,

34].

Gravelius compactness index [

35,

36] is the ratio of the basin perimeter to the circumference of a circle with the same area. A value of 1 corresponds to a perfectly circular basin, and the index increases with elongation or irregular basin boundaries.

Constant of channel maintenance [

30] is a geomorphological parameter representing the ratio of a watershed’s drainage area to its total channel length, often defined as the inverse of drainage density. It indicates the drainage area required to maintain one unit of channel length and is used to classify watershed texture and erodibility, with higher values generally meaning lower erodibility and coarser texture.

Lemniscate ratio (K) corresponds to the ratio between the surface of a lemniscate of same length over the basin area [

37]. A higher value of K (K > 2) indicates a more elongated basin, which generally results in faster hydrological response times and potentially higher sediment yield, while lower values (K ≤ 1) are associated with more compact or circular basins, where runoff is distributed more evenly over time.

Finally, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the full set of morphometric parameters to identify the main factors controlling basin morphology and to explore inter-variable relationships. The PCA was conducted in R using the built-in prcomp() function (after appropriate centering and scaling).

A multiple linear regression analysis was performed to quantify the relative contribution of morphometric controls on BDI variability. Predictor variables for the multiple linear regression were selected based on the results of the principal component analysis, which was used to identify the dominant morphometric controls on BDI variability. Additional variables representing relief and runoff conditions were included to test their secondary influence, while redundant indices were excluded to limit multicollinearity.

4. Results

Badland basin morphology shows a wide range of erosional conditions controlled by geometric configuration and relief energy. The degree of transverse dissection (BDI) varies from 0.13 to 0.62, and approximately 65% of the basins exhibit values below 0.30, indicating that most catchments belong to a relatively mature geomorphic stage where fluvial incision dominates over mass wasting. Pearson correlations (

Table 1) show that BDI is strongly and negatively correlated with CR (r = –0.710) and FF (r = –0.582), and positively correlated with the GCI (r = 0.737) and K (r = 0.675). These relationships indicate that basin geometry exerts a substantially greater influence on the variability and dissection of badland basins than hydraulic or topographic parameters. In particular, transverse dissection decreases as basins become more circular and compact, a pattern that is consistent with mature badland morphology.

These patterns are consistent with the moderate positive correlation between BDI and the Melton ratio MI (r = 0.463), indicating that transverse dissection tends to increase with relief energy.

Plotting circularity against the MI (

Figure 3a) shows that all catchments fall within the debris flow-prone field, with the highest MI values associated with steep, young basins and the lowest values with more evolved forms. This reflects the combined influence of lithological erodibility and relief energy; the marine clay lithologies in the study area are weak and easily mobilized, so basins with higher MI are more susceptible to rapid mass-wasting processes such as debris flows, which enhance channel incision and progressive reduction of BDI.

Although the correlation between drainage density and relief ratio is not significant (r ≈ 0.16), the overall trend is geomorphically meaningful (

Figure 3b). Drainage density increases with relief ratio up to ~0.75, indicating that steeper slopes and higher energy flows promote channel initiation and extension. Beyond a relief ratio of 0.90, drainage density declines as slope-dominated processes become prevalent, reducing the organization of the channel network. The black line represents the regression line for all data points (A), while the red line shows the regression for basins with relief ratios greater than 0.90 (B).

Figure 3c shows the relationship between mean basin slope and relief ratio. As RR increases, basin and channel slopes become steeper, concentrating more gravitational energy along the channels. This favors energetic processes, including channel incision and debris flows, and drives basins towards lower BDI values, indicating higher transverse dissection.

These geomorphometric relationships are statistically confirmed by the principal component analysis (

Figure 4). PC

1 explains 38.55% of total variance. PC

2 explains 18.88% and together they account for 57.42%, while the first three components reach 72.7%, indicating that most morphometric information is contained within the first two axes. PC

1 is dominated by compactness- and form-related indices, with high loadings for GCI (0.82), BDI (0.78), CR (0.74) and K (0.69), separating compact, highly dissected catchments from elongated low-incision basins. PC

2 shows moderate positive loadings for TWI (0.51) and SPI (0.47), indicating that hydrological storage and flow accumulation form a secondary and independent control on basin morphology. The Melton index exhibits moderate loadings on both PC

1 (0.43) and PC

2 (0.41), confirming its dual control by relief energy and runoff potential. Scores in the PC

1–PC

2 plane form a continuous, symmetric point cloud with no discrete clusters, suggesting that the basins represent a morphometric continuum rather than distinct geomorphic families.

To further assess the relative influence of different morphometric parameters on badland dissection, a multiple linear regression was performed with BDI as the dependent variable and the Gravelius compactness index (GCI), Melton index (MI) and relief ratio (RR) as predictors (n = 87). Predictor variables were selected based on the results of the PCA. In particular, GCI was chosen as the main geometric predictor because it showed the highest loading and the strongest association with BDI on the first principal component, thus representing the most effective morphometric descriptor of basin geometry. Relief ratio and Melton index were included to represent relief-related and runoff-related controls, respectively, corresponding to additional physical processes identified by the PCA.

The resulting model is:

and explains 57.8% of the variance in BDI (R

2 = 0.578; adj. R

2 = 0.563;

p < 0.001). GCI emerges as the dominant predictor (β = 0.58,

p < 0.001), while MI shows a weaker and statistically non-significant effect (β = 0.08,

p = 0.15) and RR exerts a moderate negative influence (β = −0.22,

p = 0.02). These results confirm that basin compactness is the primary control on the degree of badland dissection expressed by the BDI, with relief contributing a secondary modulation.

5. Discussion

The results demonstrate that the geomorphic evolution of badland basins is strongly conditioned by geometric configuration and transverse dissection. High BDI values correspond to juvenile morphologies dominated by mass wasting, where slope instability and vertical scarp retreat control sediment production and transfer. In this early phase, drainage networks remain poorly developed and energy expenditure is concentrated on wall degradation and removal of landslide debris. As basins evolve, BDI decreases and channel incision becomes more efficient, marking the transition to fluvially dominated erosion. The finding that most BDI values are below 0.30 indicates that the majority of studied basins have reached a mature stage of development characterized by organized channel networks and well-defined runoff pathways. In particular, BDI decreases as the basin becomes more circular and compact, indicating better-developed badland topography, as observed in other Italian regions such as Sicily and Marche [

9,

10,

14].

The correlation structure provides further hydrological insight. High circularity and form factor values indicate shorter concentration times and a greater predisposition to flash flooding, because simultaneous rainfall input produces rapid convergence of flow toward the outlet [

38]. Conversely, elongated catchments distribute runoff more uniformly and allow for greater infiltration, reducing peak discharges [

39,

40].

Figure 3 summarizes the combined effects of (a) basin and channel slope, (b) lithological resistance and erodibility, and (c) rainfall erosivity and flow power on badland evolution.

Panel (a) shows that all basins fall within the debris flow-prone field of the CR–MI diagram, indicating that weak clay lithologies combined with high relief energy favor rapid, episodic sediment transfer. Young basins with high Melton ratios are more susceptible to debris flows due to steep slopes and limited infiltration, while more mature basins retain the same process style but exhibit lower relief energy.

Panel (b) shows that drainage density increases with relief ratio up to ~0.75. The weak but meaningful trend between drainage density and relief ratio reflects a shift in erosion dynamics. At low to moderate relief ratios, higher gradients promote channel incision and therefore increase drainage density. However, when relief ratio exceeds a threshold (~0.90), slope processes outpace channel incision, increasing the critical drainage area needed to sustain headwater channels and reducing network density. This behavior agrees with the transition from fluvial threshold control to slope-dominated mass wasting described by Howard [

41]. Convex slope profiles observed in the field confirm this shift, indicating that diffusive mass wasting, rather than fluvial incision, shapes the hillslopes.

Panel (c) illustrates how increasing basin and channel slopes enhance stream power and shear stress, especially under intense storms, accelerating gully deepening and cross-dissection and thus driving basins towards lower BDI values.

The role of rainfall erosivity and flow power suggested by

Figure 3 is consistent with recent studies in the Basilicata region [

21,

22], which document increasing tendencies in sub-daily rainfall extremes and storm erosivity over the last decades. The combination of steeper basin and channel slopes, weak clayey lithologies and more frequent or higher-intensity storms enhances the efficiency of sediment mobilization along badland channels, reinforcing the transition from juvenile, mass-wasting-dominated morphologies towards mature, strongly dissected basins with low BDI values.

The PCA quantitatively supports this interpretation. The fact that more than half of the total variance (57.42%) is captured by the first two components, and that PC1 is dominated by compactness indices, demonstrates that geometric configuration is the primary driver of morphometric variability. Hydrological indices load primarily on PC2 and are nearly orthogonal to compactness variables, confirming their statistical independence. The absence of clustering in the score plot indicates continuous morphometric adjustments rather than discrete evolutionary stages, supporting the idea that badland development in the study area progresses along a gradient of incision and slope transport efficiency. The dual loading of the Melton index confirms its role as a transition parameter linking relief energy with geometric form.

Building on this, the multiple linear regression analysis confirms and quantifies these relationships. BDI was modeled as a function of GCI, MI, and RR, representing the three main controlling processes identified by PCA: basin geometry, relief-related energy, and runoff-driven channel power. This analysis reinforces that compactness is the dominant control on transverse dissection, while slope modulates incision efficiency and runoff-driven metrics play a secondary role at the basin scale.

Overall, the combined geomorphometric, PCA, regression, and evidence shown in

Figure 3 suggests that the studied badlands evolve from steep, debris flow-dominated systems toward progressively more incised and channelized forms, yet maintain high susceptibility to rapid sediment transfer even at mature stages. The steep slope angles (mean 40–45°) imply that debris flow initiation can occur even under moderate rainfall, consistent with observed field conditions. These findings reinforce the interpretation that slope instability, runoff concentration, and limited infiltration capacity collectively drive badland evolution in the study area.

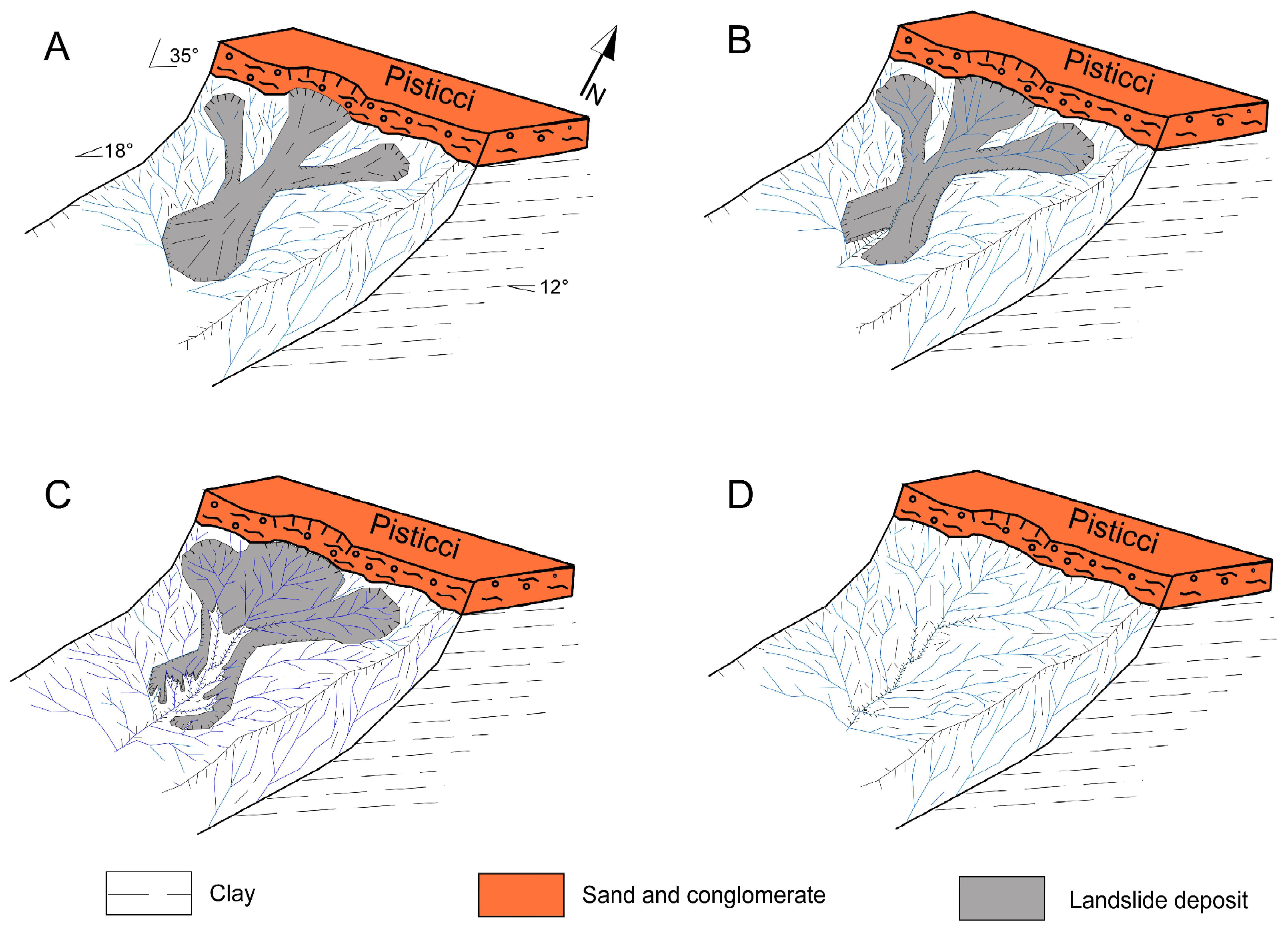

Conceptual Model of Badland Evolution in the Bradanic Trough

Based on data from field observations, morphometric analysis, and the literature [

18,

19,

42] a conceptual model of badland evolution in the high-energy relief of the Bradanic Trough hillslopes (

Figure 5) was developed. In this framework, the Badland Dissection Index (BDI) provides a quantitative measure of the degree of internal dissection and drainage maturity, allowing each evolutionary stage to be associated with a characteristic range of BDI values. Each morphological stage depicted in

Figure 5 can therefore be associated with a specific range of BDI values, so that the qualitative evolutionary sequence from landslide-dominated, elongated basins to mature, circular and densely dissected basins can be expressed as a quantitative trajectory in terms of drainage development.

The presence of a caprock controls the gradient of the upper relief, consistent with typical badland morphodynamics [

43,

44]. The higher friction angle of sands and conglomerates sustains slopes between 25° and 35°, reaching up to 45°, imposing steep inclinations on the underlying clays. Field observations and slope profiles reveal convex catchment shapes, indicating dominance of linear diffusional mass wasting. At hilltops, the caprock’s angle of repose supports steep slopes that the lower angle of repose clays cannot maintain, resulting in failure and active mass wasting on the steeper slopes.

Initially, the basin is elongated with near-vertical upper slopes and a landslide body occupying much of the mid to lower basin. Rainfall-driven runoff incises the upper slopes vertically, progressively widening slope edges. Steeper slopes favor rapid runoff and reduced infiltration, dissipating most system energy on landslide dismantling and hydrographic network reorganization.

As the landslide deposit erodes, incision and sediment transport equilibrate, rounding the basin’s highest parts and accumulating sediments mid-lower basin. Transverse gullies begin to form, and basin morphology evolves from elongated to more circular, equalizing the distance from perimeter to outlet. This synchronizes runoff delivery, producing sharp discharge peaks after rains, enhancing upstream gully incision and downstream sediment transport. The basin thus enters an advanced juvenile phase characterized by progressive gully deepening and continual small-scale shallow mass movements on upper slopes, sustaining hillslope rejuvenation.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces the Badland Dissection Index (BDI), a simple, dimensionless morphometric parameter that quantifies the internal dissection and drainage maturity of badland basins. The index was applied to 87 calanchi basins developed on marine clays in the Ionian sector of Basilicata (southern Italy), where BDI values range from 0.13 to 0.62. Approximately 65% of the basins exhibit values lower than 0.30, indicating that most catchments are in a relatively mature geomorphic stage dominated by organized fluvial incision rather than mass-wasting processes.

Correlation analysis shows that BDI is strongly related to basin shape and compactness indices (r = −0.71 with circularity ratio, r = −0.58 with form factor, r = 0.74 with Gravelius compactness index, r = 0.68 with Lemniscate index) and moderately related to relief (r = 0.46 with Melton ratio), highlighting the primary control exerted by basin geometry on badland dissection and the secondary role of relief energy. Principal component analysis confirms this pattern; compactness-related variables and BDI dominate the first component, which explains 38.6% of the total variance, while hydrological indices define an independent second component. Together, the first two components account for 57.4% of the total variance, indicating that most morphometric variability is organized along a geometric–hydrological gradient.

A multiple linear regression model further demonstrates that BDI can be effectively predicted from a limited subset of traditional indices, with the Gravelius compactness index emerging as the dominant predictor (R2 = 0.58; adj. R2 = 0.56), while the Melton index and relief ratio exert weaker or secondary influences once basin compactness is accounted for.

These quantitative results demonstrate that BDI is not a mere reformulation of existing morphometric parameters, but an integrative metric that synthesizes basin compactness and channel network organization into a single measure of drainage development. Because it requires only the relative lengths of main and subsidiary channels, BDI can be readily applied to other badland systems and highly dissected erosional landscapes using medium-resolution DEMs and orthophotos, providing a practical tool for regional morphodynamic comparisons and for monitoring temporal changes in badland evolution where repeat topographic datasets are available.