Microplastics in Wastewater Systems of Kazakhstan and Central Asia: A Critical Review of Analytical Methods, Uncertainties, and Research Gaps

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Summarize MP occurrence in influent, effluent, and sludge from regional WWTPs and benchmark these values against global datasets.

- Critically evaluate analytical methods and their uncertainties—covering sampling, pre-treatment, and detection—that limit cross-study comparability and hinder mass-balance modeling.

- Propose a regional research agenda prioritizing protocol standardization, interlaboratory comparisons, and long-term monitoring to enable robust assessment and mitigation of MP pollution in developing contexts.

2. Methodology of the Review

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Document type: peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, or institutional/agency reports with traceable methods; review papers were included when providing systematic synthesis of WWTP evidence.

- Matrix/process scope: explicit focus on WWTP influent, effluent, sludge, or directly related process streams (e.g., primary/secondary clarifiers, tertiary/advanced polishing).

- Methodological transparency: clear reporting of sampling (location, volume, dates), pre-treatment (e.g., digestion, density separation), and identification technique (microscopy, µ-FTIR, Raman, Py-GC/MS), including minimum size threshold.

- Quantitative output: at least one quantitative metric, such as MP concentration (e.g., particles/L for liquids; particles/kg dry weight (DW) for sludge) and/or removal efficiency (%); when available, QA/QC indicators (blanks, spike recoveries, Limit of Detection/Limit of Quantification (LoD/LoQ)) were recorded.

- Studies dealing exclusively with marine or surface-water MPs, without linkage to wastewater sources.

- Records with insufficient methodological detail (e.g., no size cutoff or no analytical method stated).

- Publications focusing solely on modeling or ecotoxicological effects unrelated to WWTP matrices/streams.

- Non-scientific particles (news, editorials, non-traceable gray literature).

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis Variables

- Study level (n = 63 studies with 106 records). Each study corresponds to a unique publication–WWTP (or set of WWTPs) with a consistent methodological description. The following fields were extracted:

- Study ID, Reference, Country, Region, Plant Name, Population served, Average flow, Treatment train (primary/secondary/tertiary/advanced).

- Sampling period start, Sampling period end, Sampling method, Number of campaigns, Seasonality covered.

- QA/QC reporting: Blanks reported (Y/N), Spike recovery reported (Y/N), Spike recovery (%), LoD/LoQ reported (Y/N).

- Notes (e.g., particularities, deviations from standard protocols, ancillary controls).

- 2.

- Observation level (n = 402 matrices observations). Each observation is a matrix-stage datum extracted from a study (possibly multiple per study). The following variables were recorded:

- Observation ID, Study ID, Matrix (influent/effluent/sludge), Stage (e.g., primary clarifier, activated sludge, tertiary filtration, MBR, etc.).

- Microscopy (for MP counting), Size range (µm), Mass (when reported), Concentration unit, Concentration mean, Removal efficiency (%).

- Spectroscopy (for polymer ID), Dominant polymers, Polymer fractions (%), Dominant shape.

- Comments (e.g., analytical caveats, sub-LoQ handling).

2.4. Quality Assessment and Potential Sources of Bias

3. Global Evidence and Analytical Challenges

3.1. Overview of Global Evidence

3.1.1. Geographical Variability and Plant Typologies

3.1.2. Scale and Process Configurations

3.1.3. Global Occurrence Across Matrices

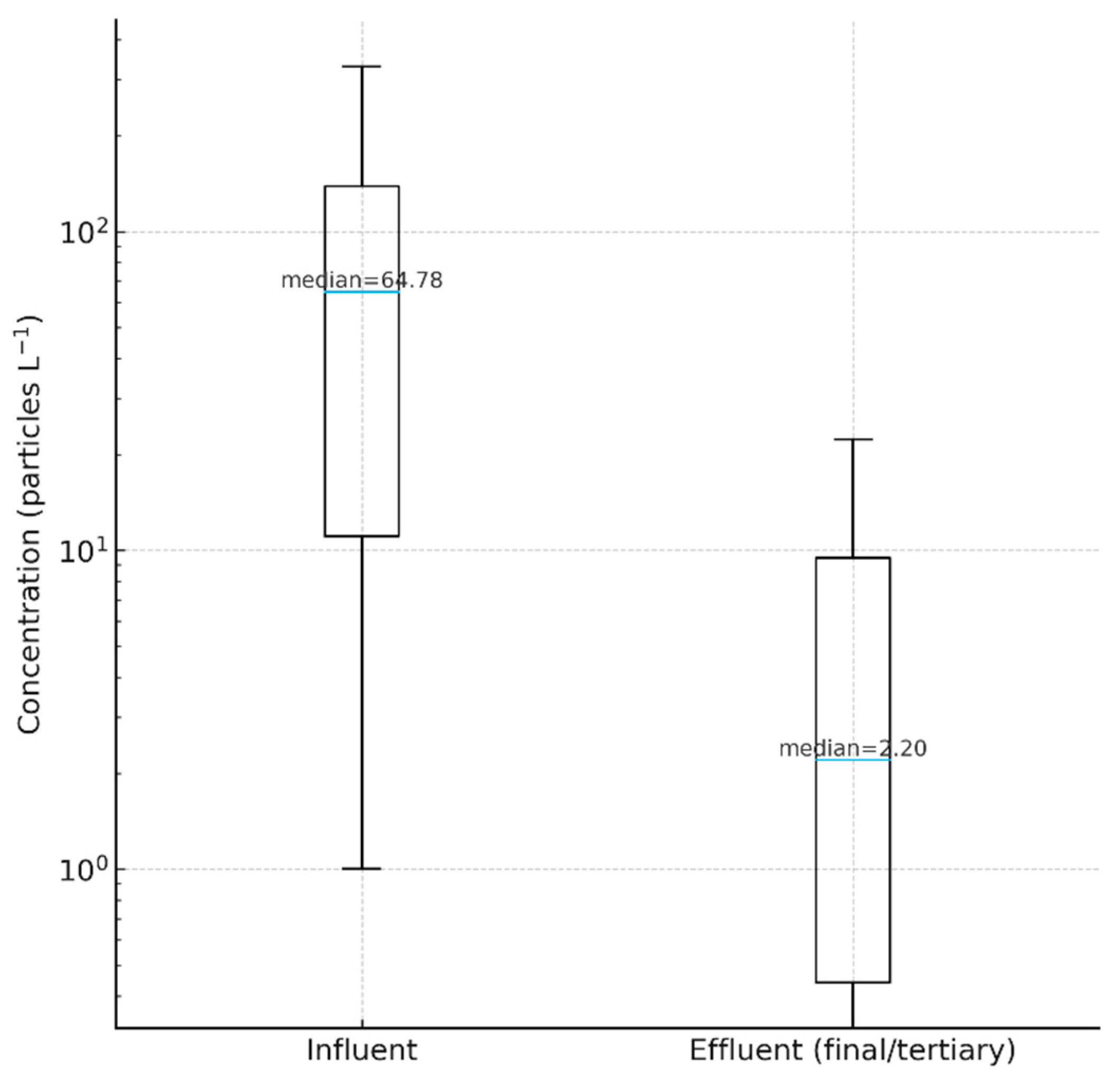

- Influent (n = 75): p10–p90 = 2.8–338; median 64.8; min 1.0; max 8.6 × 104.

- Effluent (final/tertiary; n = 129): p10–p90 = 0.096–34.1; median 2.2; min 0; max 6.4 × 103.

3.1.4. Polymer Distribution and Particle Types

3.1.5. Average Removal Efficiency (Secondary vs. Tertiary/Advanced)

- Secondary treatment: median 85.5%; IQR 65.0–96.5%.

- Tertiary/advanced: median 95.0%; IQR 74.4–98.5%.

3.1.6. Sludges (Biosolids): Sink, Pathway, and Agronomic Trade-Offs

3.2. Analytical and Methodological Uncertainties

3.2.1. Sampling Design and Representativeness

3.2.2. Minimum Detectable Size (Size Cut-Off)

- Nominal vs. effective cut-off. Many papers report the mesh/pore size of sieves/filters (e.g., 50 or 100 µm), but the effective detection limit is often co-determined by spectral resolution/segmentation (µ-FTIR/Raman) and by filter loading/clogging, which can retain particles smaller than the nominal mesh; or, conversely, allow elongated fibers to align and pass through; both effects distort the true cut-off.

- Processing cut-off vs. analytical cut-off. The sample-processing threshold (after sieving/digestion) may differ from the identification threshold (what the optical/µ-FTIR/Raman workflow can reliably classify). Studies rarely report both, making comparisons non-like-for-like.

3.2.3. Analytical Identification

3.2.4. Recovery and QA/QC Practices

- Co-reporting structure. Only a small subset documents QA/QC comprehensively: 7 studies report all three elements (blanks + spikes + LoD/LoQ), 15 report two, 26 report only one, and 13 report none. Thus, most papers lack at least one critical QA/QC component.

- Spectroscopy vs. QA/QC reporting. Comparing studies that used any spectroscopic identification (µ-FTIR/Raman/Py-GC/MS) with those that did not shows no clear advantage in QA/QC transparency: blanks are reported in ≈92% in both groups; spike-recovery reporting is ≈36% in both; LoD/LoQ remains low overall (≈15% with spectroscopy vs. 33% without), underscoring that LoD/LoQ is often framed around counting thresholds rather than spectral confirmation limits.

4. Regional Synthesis: Kazakhstan and Central Asia

4.1. Regional WWTP Infrastructure and Implications for MP Persistence

4.2. Evidence Beyond the Plant Fence Line (Rivers, Lakes) and Polymer Profiles

4.3. Treatment Trains, Upgrades, and Expected Removal

4.4. Why Standardization and Longitudinal Data Are Essential

5. Comparative Analysis

5.1. Central Asian WWTP Microplastics in a Global Context

5.2. Rivers Receiving WWTP Effluents: Central Asia vs. Global Case Studies

6. Research Gaps and Regional Priorities (2025–2030)

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. The plastic in microplastics: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.A.; Liu, J.; Tesoro, A.G. Transport and fate of microplastic particles in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2016, 91, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miino, M.C.; Galafassi, S.; Zullo, R.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C. Microplastics removal in wastewater treatment plants: A review of the different approaches to limit their release in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyare, P.U.; Ouki, S.K.; Bond, T. Microplastics removal in wastewater treatment plants: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 2664–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, T. A review of the removal of microplastics in global wastewater treatment plants: Characteristics and mechanisms. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maw, M.M.; Boontanon, N.; Aung, H.K.Z.Z.; Jindal, R.; Fujii, S.; Visvanathan, C.; Boontanon, S.K. Microplastics in wastewater and sludge from centralized and decentralized wastewater treatment plants: Effects of treatment systems and microplastic characteristics. Chemosphere 2024, 361, 142536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conley, K.; Clum, A.; Deepe, J.; Lane, H.; Beckingham, B. Wastewater treatment plants as a source of microplastics to an urban estuary: Removal efficiencies and loading per capita over one year. Water Res. X 2019, 3, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Koistinen, A.; Setälä, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution—Removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Res. 2017, 123, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lares, M.; Ncibi, M.C.; Sillanpää, M.; Sillanpää, M. Occurrence, identification and removal of microplastic particles and fibers in conventional activated sludge process and advanced MBR technology. Water Res. 2018, 133, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prus, Z.; Wilk, M. Microplastics in sewage sludge: Worldwide presence in biosolids, environmental impact, identification methods and possible routes of degradation, including the hydrothermal carbonization process. Energies 2024, 17, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatinoglu, D.; Sanin, F.D. Sewage sludge as a source of microplastics in the environment: A review of occurrence and fate during sludge treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, C.; González-Pleiter, M.; Leganés, F.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; Rosal, R. Fate of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants and their environmental dispersion with effluent and sludge. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, F.; Meza, P.; Eguiluz, R.; Casado, F.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Geissen, V. Evidence of microplastic accumulation in agricultural soils from sewage sludge disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallek, M.; Barceló, D. Sustainable analytical approaches for microplastics in wastewater, sludge, and landfills: Challenges, fate, and green chemistry perspectives. Adv. Sample Prep. 2025, 14, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Parker-Jurd, F.N.F.; Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C. Examining the release of synthetic microfibres to the environment via two major pathways: Atmospheric deposition and treated wastewater effluent. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmakhanova, M.S.; Diaz de Tuesta, J.L.; Malakar, A.; Gomes, H.T.; Snow, D.D. Wastewater treatment in Central Asia: Treatment alternatives for safe water reuse. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pu, S.; Lv, X.; Gao, Y.; Ge, L. Global trends and prospects in microplastics research: A bibliometric analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orona-Návar, C.; García-Morales, R.; Loge, F.J.; Mahlknecht, J.; Aguilar-Hernández, I.; Ornelas-Soto, N. Microplastics in Latin America and the Caribbean: A review on current status and perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 309, 114698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malematja, K.C.; Melato, F.A.; Mokgalaka-Fleischmann, N.S. The occurrence and fate of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants in South Africa and the degradation of microplastics in aquatic environments—A critical review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgalaka-Fleischmann, N.S.; Melato, F.A.; Netshiongolwe, K.; Izevbekhai, O.U.; Lepule, S.P.; Motsepe, K.; Edokpayi, J.N. Microplastic occurrence and fate in the South African environment: A review. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIZ. Baseline Study on Microplastics in ASEAN. 2024. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2024-en-baseline-study-on-microplastics.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Nweke, N.D.; Agbasi, J.C.; Ayejoto, D.A.; Onuba, L.N.; Egbueri, J.C. Sources and Environmental Distribution of Microplastics in Nigeria. In Microplastics in African and Asian Environments: The Influencers, Challenges, and Solutions; Egbueri, J.C., Ighalo, J.O., Pande, C.B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbueri, J.C.; Agbasi, J.C.; Abba, S.I.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Mirzayi, F.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Nweke, N.D.; Pande, C.B.; Ighalo, J.O. Microplastic Contamination in Nigerian Treated Waters and Packaged (Sachet, Bottled) Sources: Trends, Regional Disparities, and Policy Implications for Sustainable Practices. Anal. Lett. 2025, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, T.; Mohamad Riza, Z.H.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Abu Hasan, H.; Ismail, N.; Othman, A.R. Microplastic removal in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) by natural coagulation: A literature review. Toxics 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Recommended Harmonized Protocol for Sampling, Analysis, and Monitoring of Microplastics in Sewage Treatment Plants and Riverine Environments in ASEAN; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Kanagawa, Japan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhaxylykova, D.; Alibekov, A.; Lee, W. Seasonal variation and removal of microplastics in a Central Asian urban wastewater treatment plant. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 205, 116597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salikova, N.S.; Rodrigo-Ilarri, J.; Makeyeva, L.A.; Rodrigo-Clavero, M.-E.; Tleuova, Z.O.; Makhmutova, A.D. Monitoring of microplastics in water and sediment samples of lakes and rivers of the Akmola Region (Kazakhstan). Water 2024, 16, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Y.; Khusanov, A.; Yuldashov, M.; Vorobiev, E.; Rakhmatullina, S.; Rednikin, A.; Tashbaev, S.; Mamatkarimova, S.; Ruchkina, K.; Namozov, S.; et al. Microplastics in the Syr Darya River tributaries, Uzbekistan. Water 2023, 15, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Q.L.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Ni, B.-J. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal. Water Res. 2019, 152, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Int-Veen, I.; Löder, M.G.J.; Primpke, S.; Gerdts, G. Identification of microplastic in effluents of wastewater treatment plants using focal plane array-based micro-Fourier-transform infrared imaging. Water Res. 2017, 108, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagg, A.S.; Sapp, M.; Harrison, J.P.; Ojeda, J.J. Identification and quantification of microplastics in wastewater using focal plane array-based reflectance micro-FT-IR imaging. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 6032–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, S.; Song, B.; Burbage, C. Quantifying and identifying microplastics in the effluent of advanced wastewater treatment systems using Raman microspectroscopy. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykkemark, J.; Mattonai, M.; Vianello, A.; Gomiero, A.; Modugno, F.; Vollertsen, J. Py–GC–MS analysis for microplastics: Unlocking matrix challenges and sample recovery when analyzing wastewater for polypropylene and polystyrene. Water Res. 2024, 261, 122055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, R.R.; Lusher, A.L.; Olsen, M.; Nizzetto, L. Validation of a method for extracting microplastics from complex, organic-rich, environmental matrices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7409–7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordachescu, L.; Papacharalampos, K.; Barritaud, L.; Denieul, M.-P.; Plessis, E.; Baratto, G.; Julien, V.; Vollertsen, J. Microplastics in an advanced wastewater treatment plant: Sustained and robust removal rates unfazed by seasonal variations. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2024, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.M.; Waldron, S.; Gauchotte-Lindsay, C. Average daily flow of microplastics through a tertiary wastewater treatment plant over a ten-month period. Water Res. 2019, 163, 114909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, A.M.; O’Connell, B.; Healy, M.G.; O’Connor, I.; Officer, R.; Nash, R.; Morrison, L. Microplastics in sewage sludge: Effects of treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Prasetya, K.D.; Hanun, J.N.; Bui, H.M.; Rajendran, S.; Kataria, N.; Khoo, K.S.; Wang, Y.-F.; You, S.-J.; Jiang, J.-J. Microplastic contamination in sewage sludge: Abundance, characteristics, and impacts on the environment and human health. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 31, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, A.E.; Köper, I. Microplastics in biosolids: A review of ecological implications and methods for identification, enumeration, and characterization. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooge, A.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Heinze, W.M.; Lyngsie, G.; Ramos, T.M.; Sandgaard, M.H.; Vollertsen, J.; Syberg, K. Fate of microplastics in sewage sludge and in agricultural soils. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Environmental Performance Reviews: Kazakhstan, 3rd ed.; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://unece.org/ru/info/Environment-Policy/Environmental-Performance-Reviews/pub/2180 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning Urban Wastewater Treatment (Recast)—COM(2022) 541 Final, Brussels. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022PC0541 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Setälä, O.; Heinonen, M.; Koistinen, A. How well is microlitter purified from wastewater?—A detailed study on the stepwise removal of microlitter in a tertiary level wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2017, 109, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Dong, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, W.M. Microplastics in a municipal wastewater treatment plant: Fate, dynamic distribution, removal efficiencies, and control strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, T.; Üstün, G.E.; Kaya, Y. Characteristics and seasonal variation of microplastics in the wastewater treatment plant: The case of Bursa deep sea discharge. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, E.; Yücel, N.; Şahutoğlu, S.M. Microplastic composition, load and removal efficiency from wastewater treatment plants discharging into Orontes River. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, G.E.; Bozdaş, K.; Can, T. Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in an urban wastewater treatment plant in Turkey. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 310, 119890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardar, S.; Onay, T.T.; Demirel, B.; Kideys, A.E. Evaluation of microplastics removal efficiency at a wastewater treatment plant discharging to the Sea of Marmara. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M.; Yurtsever, M.; Karadagli, F. Microplastic removal by aerated grit chambers versus settling tanks of a municipal wastewater treatment plant. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 38, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; van Alst, N.; Vollertsen, J. Quantification of microplastic mass and removal rates at wastewater treatment plants applying focal plane array (FPA)-based Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) imaging. Water Res. 2018, 142, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, S.; Binelli, A.; Pittura, L.; Avio, C.G.; Della Torre, C.; Parenti, C.C.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F. The fate of microplastics in an Italian wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, P.J.; Dou, M.; Wang, C.; Li, G.Q.; Jia, R. Abundance and removal characteristics of microplastics at a wastewater treatment plant in Zhengzhou. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 36295–36305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayo, J.; Olmos, S.; López-Castellanos, J. Microplastics in an urban wastewater treatment plant: The influence of physicochemical parameters and environmental factors. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gies, E.A.; LeNoble, J.L.; Noël, M.; Etemadifar, A.; Bishay, F.; Hall, E.R.; Ross, P.S. Retention of microplastics in a major secondary wastewater treatment plant in Vancouver, Canada. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Heinonen, M.; Pääkkönen, J.-P.; Vahtera, E.; Mikola, A.; Setälä, O.; Vahala, R. Do wastewater treatment plants act as a potential point source of microplastics? Preliminary study in the coastal Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 72, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Saad, M.; Renault, N.; Tassin, B. Microplastic contamination in an urban area: A case study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Garneau, D.; Sutton, R.; Chu, Y.; Ehmann, K.; Barnes, J.; Fink, P.; Papazissimos, D.; Rogers, D.L. Microplastic pollution is widely detected in US municipal wastewater treatment plant effluent. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroody, S.S.A.; Hashemi, S.H.; van Gestel, C.A.M. Factors affecting microplastic retention and emission by a wastewater treatment plant on the southern coast of Caspian Sea. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 128179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, C.; Kumbur, H.; Gökdağ, K.; Kıdeyş, A.E.; Sanchez-Vidal, A. Microplastics composition and load from three wastewater treatment plants discharging into Mersin Bay, north eastern Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Cao, G.; Xie, G.; Xing, D.; Liu, B. Investigation and fate of microplastics in wastewater and sludge filter cake from a wastewater treatment plant in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.Y.; Sun, Q.; Xia, S.Y.; Tong, D.; Ni, H.G. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants and their contributions to surface water and farmland pollution in China. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, C.-S.; Cheon, S.-J.; Choi, K.-I.; Kim, J.; Jung, J.; Yoon, J.-K.; Lee, S.-H.; Jeong, D.-H. Detection of microplastic traces in four different types of municipal wastewater treatment plants through FT-IR and TED-GC-MS. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saur, T.; Paillet, F.; Robert, S.; Alibar, J.C.; Loret, J.F.; Barillon, B. Fate of microplastic pollution along the water and sludge lines in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Microplastics 2025, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.; Azadkhah, S.; Farahani, H.; Uddin, S.; Khan, F.R. Microplastics in wastewater outlets of Bandar Abbas city (Iran): A potential point source of microplastics into the Persian Gulf. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretas Alvim, C.; Bes-Piá, M.A.; Mendoza-Roca, J.A. Separation and identification of microplastics from primary and secondary effluents and activated sludge from wastewater treatment plants. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 402, 126293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Huo, M.; Coulon, F.; Ali, M.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; Ying, Z.; Wang, B.; Song, X. Understanding microplastic presence in different wastewater treatment processes: Removal efficiency and source identification. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormaniec, P.; Mikosz, J. Circulation of microplastics in a municipal wastewater treatment plant with multiphase activated sludge. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.; Kerpen, J.; Prediger, J.; Barkmann, L.; Müller, L. Determination of the microplastics emission in the effluent of a municipal waste water treatment plant using Raman microspectroscopy. Water Res. X 2019, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.A.; Arellano, J.M.; Albendín, G.; Rodríguez-Barroso, R.; Quiroga, J.M.; Coello, M.D. Microplastic pollution in wastewater treatment plants in the city of Cádiz: Abundance, removal efficiency and presence in receiving water body. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzig, C.S.; Fiener, P.; Zumbülte, N. Long-term investigation on the daily variability of microplastic concentration and composition—Monitoring in the effluent of a wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wang, W.; Ren, J.; Yu, X.; Lin, L.; Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Jin, X. Microplastic abundance, characteristics, and removal in wastewater treatment plants in a coastal city of China. Water Res. 2019, 155, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzawi, M.S.M.; Funck, M.; Kunaschk, M.; Von der Esch, E.; Jacob, O.; Freier, K.P.; Schmidt, T.C.; Elsner, M.; Ivleva, N.P.; Tuerk, J.; et al. Microplastic sampling from wastewater treatment plant effluents: Best-practices and synergies between thermoanalytical and spectroscopic analysis. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziajahromi, S.; Neale, P.A.; Telles Silveira, I.; Chua, A.; Leusch, F.D.L. An audit of microplastic abundance throughout three Australian wastewater treatment plants. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Wu, R.; Chen, L.; Zhang, K.; Lam, P.K.S. Intra-day microplastic variations in wastewater: A case study of a sewage treatment plant in Hong Kong. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maw, M.M.; Boontanon, S.K.; Jindal, R.; Boontanon, N.; Fujii, S. Occurrence and removal of microplastics in activated sludge treatment systems: A case study of a wastewater treatment plant in Thailand. Eng. Access 2022, 8, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, N.; Hait, S. Occurrence and removal of microplastics in a hybrid growth sewage treatment plant from Bihar, India: A preliminary study. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, S.; Ben-Haddad, M.; Abelouah, M.R.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Alla, A.A. Occurrence, characteristics, and removal of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants located on the Moroccan Atlantic: The case of Agadir metropolis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 862, 160815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Kamdi, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Das, S.; Bafana, A.; Krishnamurthi, K.; Sivanesan, S. Characterization and removal of microplastics in a sewage treatment plant from urban Nagpur, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Hidayaturrahman, H.; Peera, S.G.; Lee, T.G. Elimination of microplastics at different stages in wastewater treatment plants. Water 2022, 14, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.; Carbery, M.; Kuttykattil, A.; Senthirajah, K.; Lundmark, A.; Rogers, Z.; SCB, S.; Evans, G.; Palanisami, T. Improved methodology to determine the fate and transport of microplastics in a secondary wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jian, Y.; Xue, Y.; Hou, Q.; Wang, L.P. Microplastics in the wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs): Occurrence and removal. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, Y. Treatment characteristics of microplastics at biological sewage treatment facilities in Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, W.; Di, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Transfer and fate of microplastics during the conventional activated sludge process in one wastewater treatment plant of China. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Liu, X.; Xing, W. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants of Wuhan, Central China: Abundance, removal, and potential source in household wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayaturrahman, H.; Lee, T.G. A study on characteristics of microplastic in wastewater of South Korea: Identification, quantification, and fate of microplastics during treatment process. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.T.; Myers, E.; Korzin, A.; Schober, D.; Schuhen, K. Long-term monitoring of microplastics in a German municipal wastewater treatment plant. Microplastics 2024, 3, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.; Stein, J.; Reinhold, L.; Barjenbruch, M.; Fuhrmann, T.; Urban, I.; Bauerfeld, K.; Holte, A. Reduction in the input of microplastics into the aquatic environment via wastewater treatment plants in Germany. Microplastics 2024, 3, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Manjón, A.; Martínez-Díez, R.; Sol, D.; Laca, A.; Laca, A.; Rancaño, A.; Díaz, M. Long-term occurrence and fate of microplastics in WWTPs: A case study in Southwest Europe. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziajahromi, S.; Neale, P.A.; Rintoul, L.; Leusch, F.D.L. Wastewater treatment plants as a pathway for microplastics: Development of a new approach to sample wastewater-based microplastics. Water Res. 2017, 112, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhao, J.; Chan, F.; Yu, X. Effects of different treatment processes in four municipal wastewater treatment plants on the transport and fate of microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, K.; Goedecke, C.; Bannick, C.-G.; Abusafia, A.; Scheid, C.; Steinmetz, H.; Paul, A.; Beleites, C.; Braun, U. Identification of microplastic pathways within a typical European urban wastewater system. Appl. Res. 2023, 2, e202200078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollertsen, J.; Hansen, A.A. Microplastic in Danish Wastewater: Sources, Occurrences and Fate; The Danish Environmental Protection Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017; Report No. 1906; Available online: https://www2.mst.dk/udgiv/publications/2017/03/978-87-93529-44-1.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Xu, Y.; Ou, Q.; Wang, X.; Hou, F.; Li, P.; van der Hoek, J.P.; Liu, G. Assessing the mass concentration of microplastics and nanoplastics in wastewater treatment plants by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3114–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-M.-T.; Truong, T.-N.-S.; Nguyen, P.-D.; Le, Q.-D.-T.; Tran, Q.-V.; Le, T.-T.; Nguyen, Q.-H.; Kieu-Le, T.-C.; Strady, E. Evaluation of microplastic removal efficiency of wastewater-treatment plants in a developing country, Vietnam. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 29, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadsuwan, K.; Babel, S. Microplastic abundance and removal via an ultrafiltration system coupled to a conventional municipal wastewater treatment plant in Thailand. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, E.A.; Habibi, M.; Haddad, E.; Hasanin, M.; Angel, D.L.; Booth, A.M.; Sabbah, I. Microplastic distributions in a domestic wastewater treatment plant: Removal efficiency, seasonal variation and influence of sampling technique. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, K.; Cui, S.; Kang, Y.; An, L.; Lei, K. Removal of microplastics in municipal sewage from China’s largest water reclamation plant. Water Res. 2019, 155, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Bi, L.; Chen, Q.; Peng, R. A systematic review of microplastics emissions in kitchens: Understanding the links with diseases in daily life. Environ. Int. 2024, 188, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatidou, G.; Arvaniti, O.S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Review on the occurrence and fate of microplastics in sewage treatment plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 367, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas Alvim, C.; Mendoza-Roca, J.A.; Bes-Piá, M.A. Wastewater treatment plant as microplastics release source—Quantification and identification techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 255, 109739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, N.; Catarino, A.I.; Declercq, A.M.; Brenan, A.; Devriese, L.; Vandegehuchte, M.; De Witte, B.; Janssen, C.; Everaert, G. Microplastic detection and identification by Nile red staining: Towards a semi-automated, cost- and time-effective technique. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, S.R.; Roscher, L.; Primpke, S.; Hufnagl, B.; Löder, M.G.J.; Gerdts, G.; Laforsch, C. Comparison of two rapid automated analysis tools for large FTIR microplastic datasets. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 2975–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaven, S.; Banks, C.J.; Pak, L.N.; Rspaev, M.K. Wastewater reuse in Central Asia: Implications for the design of pond systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musirmonov, J.; Gafurova, L.; Ergasheva, O.; Saidova, M. Wastewater treatment in Central Asia: A review of papers from the Scopus database published in English of 2000–2020. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 386, 02005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibekov, A.; Meirambayeva, M.; Yengsebek, S.; Aldyngurova, F.; Lee, W. Environmental impact of microplastic emissions from wastewater treatment plant through life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusanov, A.; Sabirov, O.; Frank, Y.; Vorobev, D.; Vorobev, E.; Rakhmatullina, S.; Tashbaev, S.; Mamatkarimova, S.; Yakhyoyev, A.; Juraev, M.; et al. Microplastic pollution of the Zrafshan river tributary in Samarkand and Navoi regions of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Green Anal. Chem. 2025, 12, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapporov, K.; Kulmatov, R.; Opp, C. Assessment of quantity and quality indicators of water resources in the Zarafshan river basin (within the territory of Uzbekistan). E3S Web Conf. 2025, 623, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, E.; Mintenig, S.M.; Besseling, E.; Koelmans, A.A. Quality criteria for the analysis of microplastic in biota samples: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10230–10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munno, K.; Lusher, A.L.; Minor, E.C.; Gray, A.; Ho, K.; Hankett, J.; Lee, C.-F.T.; Primpke, S.; McNeish, R.E.; Wong, C.S.; et al. Patterns of microparticles in blank samples: A study to inform best practices for microplastic analysis. Chemosphere 2023, 333, 138883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QUASIMEME; NORMAN Network. Microplastics Interlaboratory Study (ILS)—Report 2020; QUASIMEME: Wageningen, The Netherlands; NORMAN: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.norman-network.net/sites/default/files/files/QA-QC%20Issues/Report%20Microplastics%20ILS%20study%20QUASIMEME%202020.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- EUROqCHARM. Analysis of Microplastics in Environmental Matrices: Results of the Interlaboratory Comparison Study—EUROqCHARM; EUROqCHARM: Oslo, Norway, 2025; Available online: https://www.euroqcharm.eu/en/news/analysis-of-microplastics-in-environmental-matrices-results-of-the-interlaboratory-comparison-study (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- ISO 24187:2023; Plastics—Microplastics—General Guidance on Sampling and Analysis. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/78033/ab8efdddef164bc0b1aff6b25bfb9669/ISO-24187-2023.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- ISO 16094-2:2025; Water Quality—Analysis of Microplastics Using Microscopy Coupled with Vibrational Spectroscopy—Part 2: Drinking Water and Low-Turbidity Waters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/84460.html (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- JRC. Analytical Methods to Measure Microplastics in Drinking Water; JRC Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC136859 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- JRC. Analysing Microplastics in Drinking Water: Towards an EU Methodology; JRC Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC143205 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- GESAMP. Guidelines for the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter and Microplastics in the Ocean; Kershaw, P.J., Turra, A., Galgani, F., Eds.; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2019; Available online: http://www.gesamp.org/publications/guidelines-for-the-monitoring-and-assessment-of-plastic-litter-in-the-ocean (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- McCormick, A.R.; Hoellein, T.J.; London, M.G.; Hittie, J.; Scott, J.W.; Kelly, J.J. Microplastic in surface waters of urban rivers: Concentration, sources, and associated bacterial assemblages. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, P.; Hiscoe, R.; Moberley, I.; Bajic, L.; McKenna, N. Wastewater treatment plants as a source of microplastics in river catchments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 20264–20267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercauteren, M.; Semmouri, I.; Van Acker, E.; Pequeur, E.; Janssen, C.R.; Asselman, J. Toward a better understanding of the contribution of wastewater treatment plants to microplastic pollution in receiving waterways. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Holsen, T.M.; Baki, A.B.M. Distribution and risk assessment of microplastic pollution in a rural river system near a wastewater treatment plant, hydro-dam, and river confluence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.; Woodward, J.; Rothwell, J.J. Microplastic contamination of river beds significantly reduced by catchment-wide flooding. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, R.; Iordachescu, L.; Bäckbom, F.; Andreasson, A.; Bertholds, C.; Pollack, E.; Molazadeh, M.; Lorenz, C.; Nielsen, A.H.; Vollertsen, J. Treating wastewater for microplastics to a level on par with nearby marine waters. Water Res. 2024, 256, 121647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, S.; Cella, C.; Geiss, O.; Gilliland, D.; La Spina, R.; Mėhn, D.; Sokull-Kluettgen, B. Analytical Methods to Measure Microplastics in Drinking Water; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; p. JRC136859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooi, M.; Besseling, E.; Kroeze, C.; van Wezel, A.P.; Koelmans, A.A. Erratum to: Modeling the Fate and Transport of Plastic Debris in Freshwaters: Review and Guidance. In Freshwater Microplastics; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Wagner, M., Lambert, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besseling, E.; Quik, J.T.K.; Sun, M.; Koelmans, A.A. Fate of nano- and microplastic in freshwater systems: A modelling study. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo De Arbeloa, N.; Marzadri, A. Modeling the transport of microplastics along river networks. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 911, 168227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciornii, D.; Hodoroaba, V.-D.; Benismail, N.; Maltseva, A.; Ferrer, J.F.; Wang, J.; Parra, R.; Jézéquel, R.; Receveur, J.; Gabriel, D.; et al. Interlaboratory comparison reveals state of the art in microplastic detection and quantification methods. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 8719–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, O.; Stefaniak, E.A.; Seghers, J.; La Spina, R.; Schirinzi, G.F.; Chatzipanagis, K.; Held, A.; Emteborg, H.; Koeber, R.; Elsner, M.; et al. Towards a reference material for microplastics’ number concentration—Case study of PET in water using Raman microspectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 3045–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Gray, A.; Christiansen, S.H.; DeFrond, H.; Deshpande, A.D.; Hemabessiere, L.; Lee, E.; Mill, L.; Munno, K.; Ossmann, B.E.; et al. Critical review of processing and classification techniques for images and spectra in microplastic research. Appl. Spectrosc. 2020, 74, 989–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.; Eo, S.; Shim, W.J. A comparison of spectroscopic analysis methods for microplastics: Manual, semi-automated, and automated Fourier transform infrared and Raman techniques. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Reference | Country | Region | WWTP Name | Population Served | Average Flow (m3·d−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S001 | [48] | Finland | Europe | Viikinmäki | 800,000 | 270,000 |

| S002 | [49] | China | East Asia | Wuxi | 300,000 | 50,000 |

| S002 | [49] | China | East Asia | Wuxi | 400,000 | 70,000 |

| S003 | [10] | Finland | Europe | Viikinmäki | — | — |

| S003 | [10] | Finland | Europe | Kakolanmaki | — | — |

| S003 | [10] | Finland | Europe | Paroinen | — | — |

| S003 | [10] | Finland | Europe | Kenkaveronniemi | — | — |

| S004 | [34] | United Kingdom | Europe | — | 650,000 | 475,000 |

| S005 | [50] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Gemlik | 150,000 | 18,250 |

| S006 | [51] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Antakya | 214,000 | 28,800 |

| S006 | [51] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Serinyol | 36,000 | 3859 |

| S006 | [51] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Narlıca | 160,220 | 21,264 |

| S007 | [52] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Nilüfer–Bursa | 650,000 | 61,800 |

| S008 | [53] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Ambarlı | 2,000,000 | 360,000 |

| S009 | [54] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Karaman | 1,626,000 | 83,000 |

| S010 | [9] | USA | North-America | Plum Island | 180,000 | 83,300 |

| S010 | [9] | USA | North-America | Rifle Range Road | 53,000 | 18,900 |

| S010 | [9] | USA | North-America | Center Street | 32,000 | 11,400 |

| S011 | [55] | Denmark | Europe | Anonymized multiple | — | — |

| S012 | [56] | Italy | Europe | Anonymized | 1,200,000 | 400,000 |

| S013 | [57] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Zhengzhou | — | 300,000 |

| S014 | [58] | Spain | Europe | Cabezo Beaza | 210,000 | 35,000 |

| S015 | [39] | United Kingdom | Europe | Anonymized Scottish | 184,500 | 166,422 |

| S016 | [59] | Canada | North-America | Metro Vancouver | 1,300,000 | 493,000 |

| S017 | [60] | Finland | Europe | Viikinmäki | 800,000 | 270,000 |

| S018 | [61] | France | Europe | Seine-Centre | 240,000 | 240,000 |

| S019 | [62] | USA | North-America | Anonymized multiple | — | — |

| S020 | [63] | Iran | Western Asia | Babolsar | 120,000 | 27,000 |

| S021 | [64] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Karaduvar | 1,010,000 | 150,000 |

| S021 | [64] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Tarsus | 340,000 | 43,000 |

| S021 | [64] | Turkey | Europe–Asia | Silifke | 120,000 | 12,000 |

| S022 | [65] | China | East Asia | Harbin | — | 240,000 |

| S023 | [66] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Shenzhen | 20,000 | 10,000 |

| S023 | [66] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Shenzhen | 5000 | 3000 |

| S024 | [67] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 115,000 | 50,000 |

| S024 | [67] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 94,200 | 32,000 |

| S024 | [67] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 137,200 | 43,000 |

| S024 | [67] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 17,900 | 58,000 |

| S025 | [68] | China | East Asia | Anonymized | 1,200,000 | 400,000 |

| S026 | [69] | Iran | Western Asia | Bandar Abbas | 680,000 | 60,480 |

| S027 | [70] | Spain | Europe | Valencia | — | 40,000 |

| S028 | [71] | China | East Asia | Changchun | — | 100,000 |

| S028 | [71] | China | East Asia | Changchun | — | 20,000 |

| S029 | [72] | Poland | Europe | Anonymized | 680,000 | 165,000 |

| S030 | [73] | Germany | Europe | Rüsselsheim/Raunheim | 98,500 | 10,000 |

| S031 | [74] | Spain | Europe | Cádiz | 375,000 | 52,329 |

| S032 | [75] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized Württemberg | 15,000 | 3204 |

| S033 | [76] | China | East Asia | Multiple Xiamen | 3,500,000 | — |

| S034 | [77] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized multiple | — | — |

| S035 | [78] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized | — | 130,000 |

| S035 | [78] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized | — | 65,000 |

| S035 | [78] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized | — | 150,000 |

| S036 | [79] | China | East Asia | Shek Wu Hui | 300,000 | 84,000 |

| S037 | [80] | Thailand | Southeast Asia | Mahidol Salaya Campus | 20,000 | 3000 |

| S038 | [81] | India | South Asia | IIT Patna Campus | 360 | |

| S039 | [82] | Morocco | Africa | Aourir | 61,000 | 7000 |

| S039 | [82] | Morocco | Africa | M’zar | 421,844 | 30,000 |

| S040 | [83] | India | South Asia | Bhandewadi | 2,800,000 | 200,000 |

| S041 | [84] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 52,000 |

| S041 | [84] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 22,925 |

| S041 | [84] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 8845 |

| S042 | [14] | Spain | Europe | Madrid WWTP | 300,000 | 28,400 |

| S043 | [85] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized | 190,000 | 48,000 |

| S044 | [86] | China | East Asia | Anonymized multiple | — | 150,000 |

| S045 | [87] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 67,700 | — |

| S045 | [87] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 235,711 | — |

| S045 | [87] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized | 245,200 | — |

| S046 | [88] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Wuhan | — | 20,000 |

| S047 | [89] | China | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 70,000 |

| S047 | [89] | China | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 300,000 |

| S048 | [32] | Germany | Europe | Multiple | — | — |

| S049 | [90] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized Daegu | — | 26,545 |

| S049 | [90] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized Daegu | — | 469,249 |

| S049 | [90] | Republic of Korea | East Asia | Anonymized Daegu | — | 20,840 |

| S050 | [91] | Germany | Europe | Landau-Mörlheim | 55,000 | 14,947 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 428,000 | 52,563 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 400,000 | 43,773 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 350,000 | 42,500 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 275,000 | 49,036 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 70,000 | 17,089 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 93,000 | 4900 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 20,000 | 1529 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 100,000 | 2773 |

| S051 | [92] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized | 15,000 | — |

| S052 | [93] | Spain | Europe | Caravaca de la Cruz | 85,000 | 8000 |

| S053 | [94] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized Sydney | 1,227,150 | 308,000 |

| S053 | [94] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized Sydney | 67,130 | 17,000 |

| S053 | [94] | Australia | Oceania | Anonymized Sydney | 150,870 | 48,000 |

| S054 | [95] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Ningbo | — | 200,000 |

| S054 | [95] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Ningbo | — | 30,000 |

| S054 | [95] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Ningbo | — | 100,000 |

| S054 | [95] | China | East Asia | Anonymized Ningbo | — | 80,000 |

| S055 | [96] | Germany | Europe | Anonymized Kaiserslautern | 100,000 | — |

| S056 | [97] | Denmark | Europe | Anonymized multiple | — | — |

| S057 | [98] | China | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 500,000 |

| S057 | [98] | China | East Asia | Anonymized | — | 200,000 |

| S058 | [99] | Vietnam | Southeast Asia | Binh Hung | 425,000 | — |

| S058 | [99] | Vietnam | Southeast Asia | Thuan An | 100,000 | — |

| S058 | [99] | Vietnam | Southeast Asia | Di An | 40,000 | — |

| S058 | [99] | Vietnam | Southeast Asia | Da Lat | 53,000 | — |

| S059 | [100] | Thailand | Southeast Asia | Anonymized Bangkok | 227,660 | 120,000 |

| S060 | [101] | Israel | Southwest Asia | Karmiel | 210,000 | 30,000 |

| S061 | [102] | China | East Asia | Gaobeidian | 2,400,000 | 1,000,000 |

| Treatment Configuration/Process | Typical MP Removal Efficiency (%) | Evidence Type/Context | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary/secondary only | Often 50–90% | Global syntheses and WWTP case studies | [5,7,26] |

| Secondary + tertiary filtration/membranes | Often >95% under well-operated conditions | Global syntheses of tertiary/advanced barriers | [5,7,26] |

| Rapid/granular sand filtration (tertiary polishing) | ≈97% | Full-scale effluent polishing study | [10] |

| DAF | ≈95% | Full-scale effluent polishing study | [10] |

| Disk filters | 40–98.5% | Full-scale effluent polishing study | [10] |

| MBR treating primary effluent | ≈99.9% | Full-scale effluent polishing study | [10] |

| Central Asian plants with scattered upgrades | Quantitative % not systematically reported; expected to fall within ranges for MBR/advanced plants above | Regional case reports and infrastructure reviews | [18,34,58] |

| Study ID | Reference | Country | Region | WWTP Name | Population Served | Average Flow (m3·d−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-CA001 | [28] | Kazakhstan | Central Asia | Astana Su Arnasy WWTP | — | 254,000 |

| S-CA002 | [110] | Kazakhstan | Central Asia | Astana Su Arnasy WWTP | — | 254,000 |

| Treatment Class | Local Methods (Cut-Off and Sampling) | Central Asia Placement vs. Global | Global Effluent Benchmark * (Particles/L) | Typical global Removal Efficiency (Median, IQR) | Practical Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary only | ≥100 µm; often grab | Upper half of global range (above global median) | Median 2.2; p10–p90 0.096–34.1 | 85.5% (65.0–96.5%) | Without a post-secondary barrier, residual fibers keep effluents comparatively high. |

| Secondary + Tertiary/Advanced (filters, DAF/BAF) | ≥100 µm; mixed grab/composite | Lower deciles (better-than-typical globally) | Median 2.2; p10–p90 0.096–34.1 | 95.0% (74.4–98.5%) | Adding filtration shifts plants toward low global percentiles even with coarser analytics. |

| Membrane (MBR/MF/UF) | ≥100 µm; method-dependent | Lower deciles (aligned with best-in-class) | Median 2.2; p10–p90 0.096–34.1 | Often ≥95% | Membranes contain most MPs; fine fibers < 100 µm may persist or be under-detected if not measured. |

| Context (global high-resolution) | <100 µm; composite/flow-weighted | Limited local data at this window | Influent median 64.8; Effluent median 2.2 | Secondary 85.5%; Tertiary 95.0% | Harmonize cut-offs (<100 µm) and use composites for like-for-like comparisons. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodrigo-Clavero, M.-E.; Rodrigo-Ilarri, J.; Alimova, K.K.; Salikova, N.S.; Makeyeva, L.A.; Berdali, M. Microplastics in Wastewater Systems of Kazakhstan and Central Asia: A Critical Review of Analytical Methods, Uncertainties, and Research Gaps. Water 2026, 18, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010104

Rodrigo-Clavero M-E, Rodrigo-Ilarri J, Alimova KK, Salikova NS, Makeyeva LA, Berdali M. Microplastics in Wastewater Systems of Kazakhstan and Central Asia: A Critical Review of Analytical Methods, Uncertainties, and Research Gaps. Water. 2026; 18(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigo-Clavero, María-Elena, Javier Rodrigo-Ilarri, Kulyash K. Alimova, Natalya S. Salikova, Lyudmila A. Makeyeva, and Meiirman Berdali. 2026. "Microplastics in Wastewater Systems of Kazakhstan and Central Asia: A Critical Review of Analytical Methods, Uncertainties, and Research Gaps" Water 18, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010104

APA StyleRodrigo-Clavero, M.-E., Rodrigo-Ilarri, J., Alimova, K. K., Salikova, N. S., Makeyeva, L. A., & Berdali, M. (2026). Microplastics in Wastewater Systems of Kazakhstan and Central Asia: A Critical Review of Analytical Methods, Uncertainties, and Research Gaps. Water, 18(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010104