4.2. Impact of the Drought Events on Socio-Economic Development and Livelihood

The result of the household survey in the two districts, illustrated in

Figure 3, shows how smallholder farmers assessed a moderate degree of the impacts of drought on their socio-economic development (WAI = 0.46). Smallholder farmers rated a high degree for the impact of drought when there was a reduction in household income (WAI = 0.64) and a moderate degree of impact for health (WAI = 0.60), loss of employment (WAI = 0.59), threatened household food security (WAI = 0.56), migration (WAI = 0.51), food scarcity (WAI = 0.50), limited food preference (WAI = 0.50), homelessness and sense of loss (WAI = 0.47), and a reduction in spending on festivals (WAI = 0.43). At the same time, smallholder farmers assessed a low degree of impact of drought on affected schooling for children (WAI = 0.37) and conflicts for water in society (WAI = 0.29). The results of the focus group discussions revealed that the smallholder farmers relied upon subsistent livelihoods in the two districts. When climate change places more pressure on agriculture, smallholders become more vulnerable, especially with respect to the impacts of drought. The farmers described to a higher degree that they depended on rain for their rice cultivation, wherein the higher degree that was advised meant that they were more vulnerable to climate-related hazards [Pers. Comm. FGD1 and FGD2].

The t-test analysis also revealed that the smallholder farmers in the Bakan district shared a higher degree of the impact of droughts on their loss of employment (p-value = 0.002), reduction in household income (p-value = 0.000), food scarcity (p-value = 0.005), threatened household food security (p-value = 0.000), limited food preference (p-value = 0.000), conflicts for water in society (p-value = 0.000), migration (p-value= 0.012), and homelessness and sense of loss (p-value = 0.000). In the Barsedth district, the smallholder farmers rated homelessness and sense of loss (WAI = 0.000) to a lower degree. Conflict for water became common in the Bakan district (WAI = 0.41), especially during the dry season; however, this was not a pressing issue in the Barsedth district (WAI = 0.18). Smallholder farmers in the two studied districts shared similar views regarding the reduction in spending on festivals (p-value = 0.637), their affected schooling for children (p-value = 0.735), and health impacts (WAI = 0.346).

During a consultative meeting, CoC members, AC committees, and smallholder farmers pronounced that there were water wars during the dry season. Water for paddy fields was not equally distributed among smallholder farmers in the district. Those residing near the main irrigation could pay to gain water from supplementary irrigation [Consultative Meeting]. The capacity to access water depended on their willingness to pay for gasoline and pump machines; individual smallholder farmers used their methods and investment to obtain water for their paddy fields [Pers. Comm. Interview-1]. A district officer in the Bakan district worked with smallholder farmers on these issues, but they could not solve the water conflicts. Each farmer wished to not share the water, and they did their best to obtain water for their own paddy fields as soon as possible due to their resources. The farmers in the upper parts of the district faced difficulty in receiving sufficient water because the lower part had already blocked or pumped water for their consumption [Pers. Comm. K-3]. A commune council (CoC) in the Bakan district blamed the mismanagement of irrigation and lack of cooperation between the smallholder farmers as the cause of the water problem. Smallholder farmers did not cooperate with local authorities; they simply cared for their own paddy fields [Pers. Comm. K-5].

Comparatively, the droughts affected the socio-economic development of smallholder farmers in the Bakan district more than those in the Barsedth district (p-value = 0.000). The household survey shows that 77.6% of the respondents were employed as smallholder rice farmers, whereby 80.9% were in the Bakan district and 74.3% were in the Barsedth district. Their incomes primarily relied upon rice cultivation. When drought events occurred, it highly impacted their revenues. In the Bakan district, rice cultivation was crucial for people because most individuals owned agricultural lands. Moreover, people on the community wished to continue their traditional occupation [Pers. Comm. K-3]. A committee member of the Chamreun Pal Agricultural Cooperative described the impacts of drought in 2019, which destroyed rice fields, leading to an economic loss for smallholder farmers. Drought was becoming an increasingly severe hazard [Pers. Comm. Interview-2]. In the Barsedth district, many young people opted for rice farming as their chosen industry because there are around 200 factories in the Kampong Speu province. Thousands of jobs in non-farming industries are available for people in the Barsedth district. In addition, Barsedth is just 83 km from Phnom Penh, where there are good road conditions and transportation that facilitate people with a connection to the capital for this district. The alternative income of household members from non-farm sources reduced their vulnerabilities and risks when drought events eventually occurred [Pers. Comm. K-5].

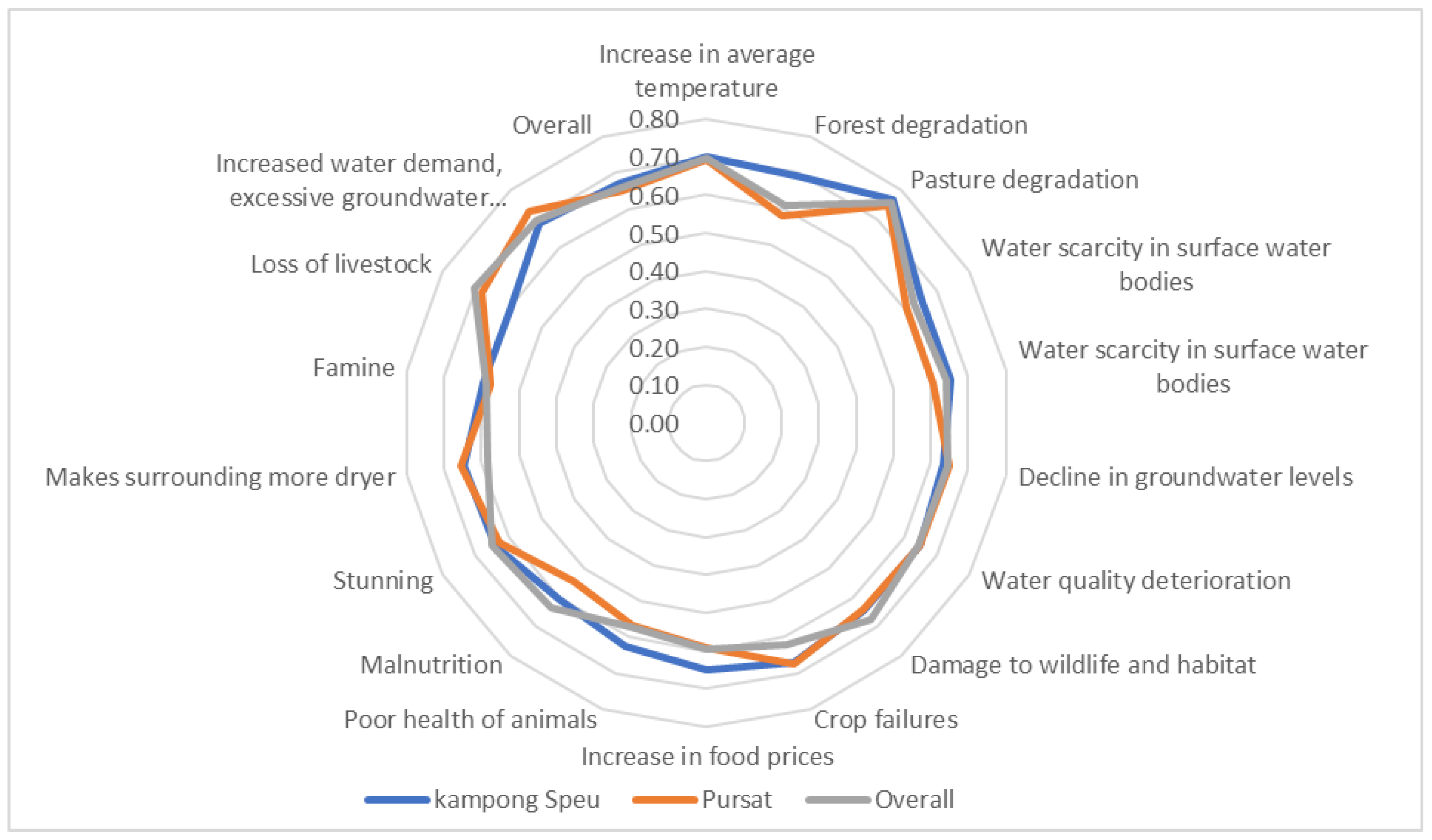

Overall, smallholder farmers rated a high degree of impact from droughts (WAI = 0.66) on their livelihoods; indeed, both districts shared this view (the Bakan district (WAI = 0.65) and the Barsedth district (WAI = 0.67)) (

p-value = 0.064). Smallholder farmers assessed that there was a high degree of pasture degradation (WAI = 0.76); increased water demand (WAI = 0.71); excessive groundwater pumping (WAI = 0.71); an increase in average temperature (WAI = 0.70); crop failures (WAI = 0.67); drier surroundings (WAI = 0.65); a greater deterioration of water quality (WAI = 0.65); declining groundwater levels (WAI = 0.64); damage to wildlife and habitats (WAI = 0.64); water scarcity in surface water bodies (WAI = 0.63); stunning (WAI = 0.63); an increase in food prices (WAI = 0.62); and forest degradation (WAI = 0.61). They rated a moderate degree of impact from droughts on the poor health of animals (WAI = 0.60); the loss of livestock (WAI = 0.59); famine (WAI = 0.58); and malnutrition (WAI = 0.57). The T-test analysis revealed that smallholder farmers in the Barsedth district rated a higher degree of the impact of droughts on forest degradation (

p-value = 0.014); water scarcity in surface water bodies (

p-value = 0.029); increases in food prices (

p-value = 0.001); the poor health of animals (

p-value = 0.010); malnutrition (

p-value = 0.001); increased water demand (

p-value = 0.040); and excessive groundwater pumping (

p-value = 0.040) (

Figure 4).

Field observation showed that the Bakan district retained greener and fuller wetlands, which are adjunct to the Tonle Sap Lake. The Barsedth district had less forest coverage and more water scarcity in its surface water bodies. Many people reduced their involvement in rice cultivation and became more involved in vegetable growing and raising livestock instead [Pers. Comm. K-5]. A committee at the Chamrostean Agricultural Cooperative observed that farmers opted to consume water from underground pumping in the Barsedth district because smallholder farmers could construct wells or pump at their houses or paddy fields [Pers. Comm. Interview-5]. For a long time, smallholder farmers benefited from the availability of natural resources, especially water from the wetlands and rains. Still, climate change has recently caused more frequent droughts and water shortages. The current water shortage and droughts have seriously affected smallholder farmers’ livelihood development [Pers. Comm. K-1].

4.3. AC Support to Deal with Drought Risk Management

In the two districts studied, the group discussions found agreement that the increased access to the five livelihood assets helped smallholder farmers improve their adaptive capacity to reduce drought impacts [FGD 1 and FDI 2]. A committee at the Agri-Productive Transport vehicle: non-cold Chain Truck worked to improve access to natural assets, human assets, physical assets, social assets, financial assets, and water during the dry season because these factors were crucial for smallholder farmers’ livelihood [Pers. Comm. Interview-4]. The ACs provided services for the smallholder farmers under the technical support of government agencies, CoCs, and NGOs. These institutions provided education on skill building and techniques and sought to bring the agricultural markets more in line with the private sector, such as supermarkets and wholesale sellers [Pers. Comm. K-2]. The multiple regression model shows that the services delivered by ACs helped to support smallholder farmers in accessing natural assets, with results of β1 = 0.226 (22.6%),

t-value = 4.366 > 1.96, and

p-value =0.000 < 0.05. In addition, the physical assets returned values of β3 = 0.206,

t-value =4.100 >1.96, and

p-value = 0.000 < 0.05. In contrast, the model predicted a significant negative contrition of the services that were delivered by ACs on social assets, with results of β4 = 0.156 **, t-value =3.132 > 1.96, and

p-value = 0.002 < 0.05. The services provided by ACs did not contribute to access to human assets, with results of β2 = 0.016,

t-value = 0.345 < 1.96, and

p-value = 0.730 > 0.05. Moreover, the access to financial support delivered results of β5 = 0.072,

t-value = 1.545 < 1.96, and

p-value = 0.123 > 0.05. Lastly, access to water from January to May for consumption delivered results of β6 = 0.077,

t-value =1.638 < 1.96, and

p-value = 0.102 > 0.05 (

Table 4).

The model revealed that the services delivered by ACs positively contribute to the access to natural assets (i.e., lakes, swamps, wells, ponds, streams, flood forests, and open access resources) and physical assets (i.e., roads, bridges, river ports, irrigations, local markets, health facilities, and school facilities for children). In the Bakan district, the ACs raised awareness and capacity building among the smallholder farmers with respect to the importance of natural assets (i.e., lakes, swamps, wells, ponds, streams, flood forests, and open-access resources). Furthermore, the knowledge and skills were helpful for smallholder farmers to become more involved in sustainable resource management [Pers. Comm. Interview-3]. The ACs in the Barsedth district had a good relationship with CoCs and NGOs in terms of mobilizing the resources to improve physical assets [Pers. Comm. Interview-5]. In 2021, Heifer International Cambodia provided the Agri-Productive Transport vehicle: a non-cold Chain Truck with a truck. The truck helped to increase the AC’s business activities for transporting the agricultural inputs of AC and for the farmers and buyers [Pers. Comm. Interview-4]. In 2021, the Accelerating Inclusive Markets for Smallholders (AIMS) also constructed a collection and distribution center of agricultural products to create a market chain; this allowed all farmers to distribute and sell their agricultural products [Pers. Comm. Interview K-5]. In the Bakan district, the ACs advised the CoCs and the District Office of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries to construct irrigation and roads to support farmers in their access to water for their paddy fields, as well as to help better facilitate the transportation of agricultural products to local markets [Pers. Comm. K-3].

In contrast, the model predicted the negative contribution of ACs to social assets, such as raising concerns about water shortage, participating in the activities of NGOs, participating in the activities of CoCs, participating in the activities of government agencies, involvement in the activities of community fishery, participation in the activities of community forestry, and being involved in community decision making. The ACs have applied a participatory approach with support from NGOs; however, smallholder farmers still felt that their participation did not contribute much to the decision-making process for community development. An AC committee in the Chamrostean Agricultural Cooperative advised that smallholder farmers in the Barsedth district had more opportunities to participate in the workshop and community meetings that were organized by government agencies and NGOs. Their participation contributed to the planning and policy implication, and they were able to raise their concerns and issues [Pers. Comm. Interview-5].

The local authority, agricultural officers, and smallholder farmers in the Bakan district agreed that the planning process at the CoC level was essential for integrating local needs and that smallholder farmers should be invited to participate. However, the local needs raised during the CoC meeting could not be fulfilled because the annual budget for the commune investment plan was mainly used for physical infrastructure only. In most cases, the yearly commune investment budget did not allocate funds for supporting AC operations, social issues, or drought management [Pers. Comm. Interview-3]. Local authorities, agricultural officers, and smallholder farmers in the Bakan district agreed that ACs did not address the promotion of social trust very well, nor did they help with promoting a culture of sharing and helping each other. In Cambodia, farmers traditionally work together, which is consistent with a vital principle of the ACs [Consultive Meeting]. All the involved agencies mainly discussed and worked to increase access to irrigation, roads, microfinance, and natural resource management, but the scope of addressing social issues remained limited [Pers. Comm. FGD 2]. During a discussion in the Bakan district, the participants announced that there were water wars occurring between the smallholder farmers; in fact, these conflicts were not predominantly caused by a lack of irrigation but were instead due to the fact that they did not share the resource. Everyone felt as if they did not receive sufficient water; however, they did not work together to solve the problem [Pers. Comm. FGD 1].

Unfortunately, the ACs did not contribute to improving access to financial assets (i.e., access to microfinances for loans, access to a commercial bank for a loan, access to local lenders for loans, participation in saving groups, and access to income generation activities), nor to access to water resources for consumption during dry seasons, such as for bathing, drinking, cooking, washing, dry rice cultivation, and crop cultivation. All the ACs applied the same core principle of share sales between the members. The smallholder farmers could invest USD 24.5 per share as shareholders and could thus expect to receive annual profits. However, the smallholder farmers who bought shares from Agri-Productive Transport vehicle: a non-cold Chain Truck in the Barsedth district had not yet received benefits from their shares in 2022 due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus of the discussion in the two districts was that the financial assets accessed by smallholder farmers through ACs remained small. The revenue produced by ACs through share sales and the distribution of agricultural inputs was not sufficient. Simultaneously, the annual benefits from shares and the available loans or savings from ACs were also small and thus made it harder to encourage people to participate. The contributions of smallholder farmers to other smallholder farmers were found to not be of much benefit. Instead, they preferred taking loans from microfinance or commercial banks with high interests because they could borrow with their demands for agricultural investment [Pers. Comm. FGD 1 and FGD 2].

Access to water was the most critical resource for smallholder farmers, especially during the dry season. In the consultative meeting, the available and accessible water for farming activities was discussed. Almost all the farmers depended on rain-fed agriculture. During the dry season, smallholder farmers had difficulty accessing water for their paddy fields. When drought events happened, as in 2018, for example, smallholder farmers needed to buy or rent pumps in order to obtain water from the nearby dikes, ponds, and cannels [Pers. Comm. Interview-1]. An officer at the District Office of Agriculture, Fishery, and Forestry in Barsedth district explained that the dikes, ponds, and cannels dried out faster and remained that way for several weeks or months. The rice of smallholder farmers who stayed away from water sources such as wetlands or cannels did not have sufficient water [Pers. Comm. K-5]. The ACs have worked closely with key stakeholders from government agencies and NGOs from district to commune levels on this issue; however, as of yet, access to water during the dry season remains unsolved [Pers. Comm. Interview-2]. In general, access to water during the dry season was not stable and was uncertain; smallholder farmers were thus challenged to maintain productivity with a lack of water during the dry season. However, Cambodia’s water from the Mekong River, Tonle Sap Lake, and other wetlands was still widely available. Still, making physical infrastructure public for smallholder farmers for the entire year has proven to be costly, especially in the dry season [Pers. Comm. K-1].

4.4. Interactions between the AC Operations, Adaptive Capacity, and Drought Impacts

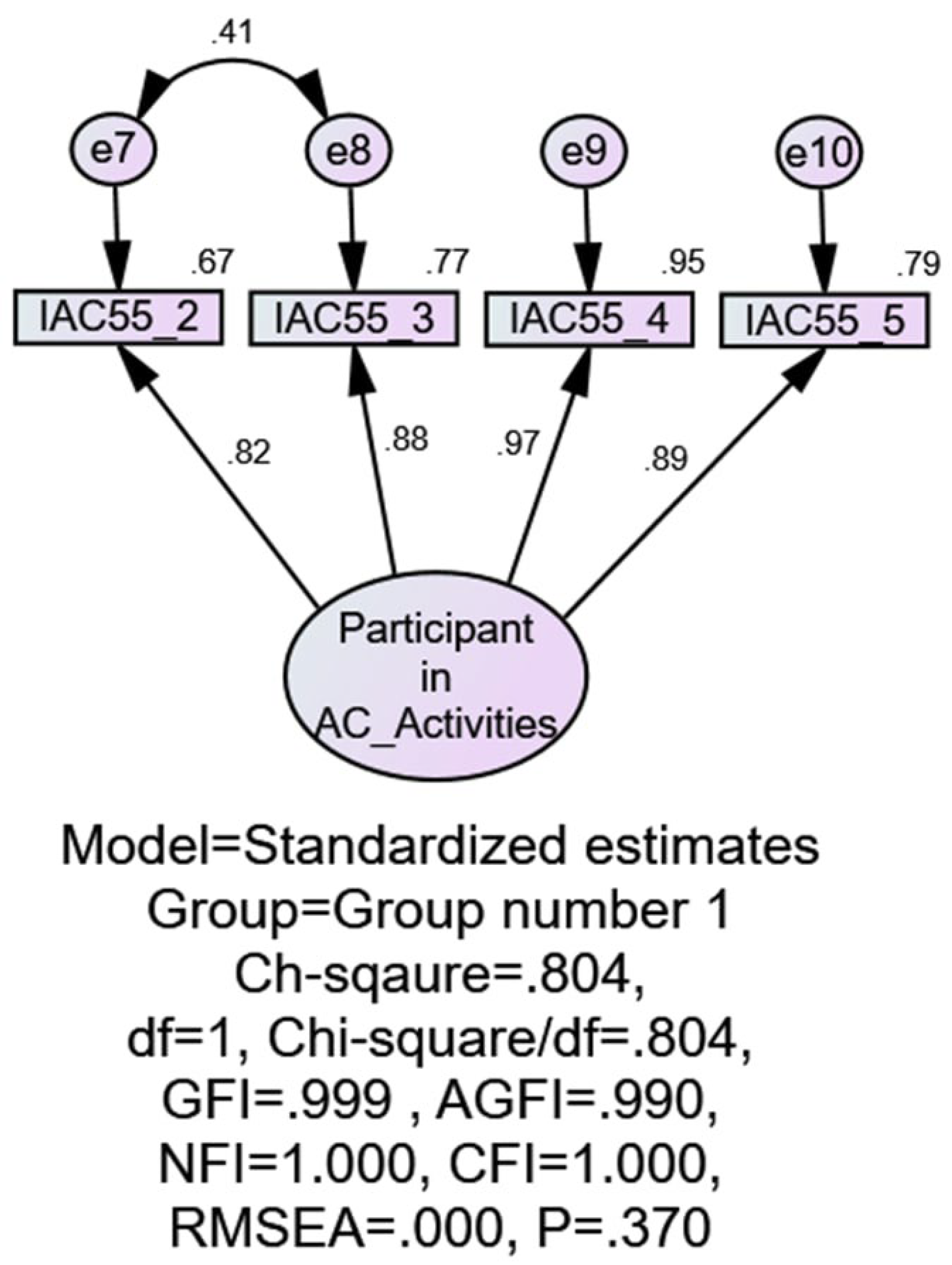

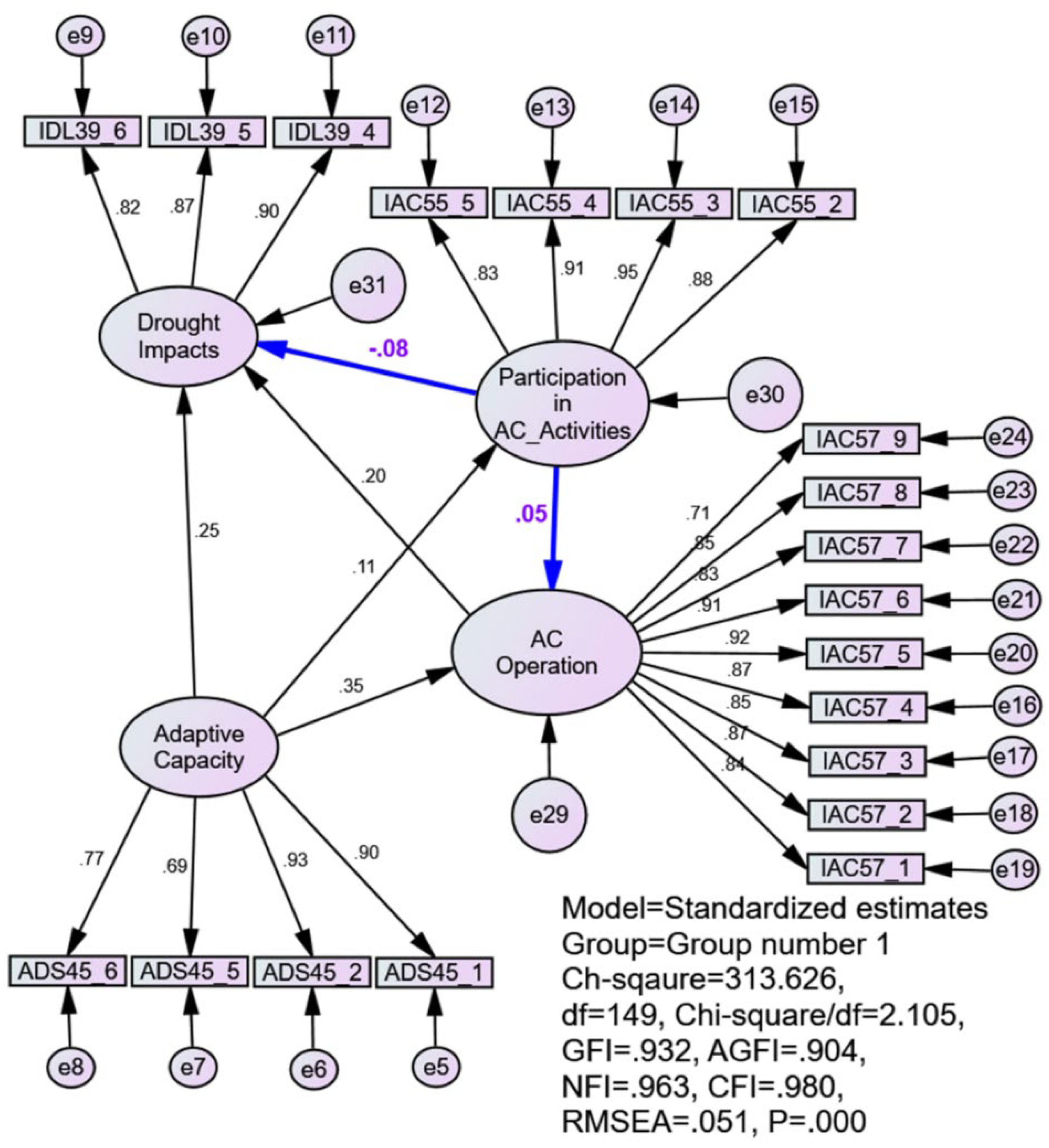

After running the CFA, the same variables illustrated in

Table 5 were also used to conduct an SEM analysis. SEM was used to test a hypothesis with the likelihood estimation method, and the SEM analysis supported the variables well. According to Anderson and Gerbing [

93], the second-order factor model was adopted to test the overall variables. The results revealed that the goodness-of-fit measurements were satisfactory (GFI = 0.932, AGF = 0.904, NFI = 0.963, CFI = 0.980, and RMSEA = 0.051) (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). Furthermore, with the goodness-of-fit assessment, they also indicated that the model was acceptable [

97]. The CFA, which applied the same variables shown in

Table 2, was also conducted before proceeding with the SEM to test the likelihood estimation method.

Table 5 and

Figure 5 show that the goodness-of-fit measurements were satisfactory (GFI = 0.932, AGFI = 0.904, NFI = 0.963, CFI = 0.980, and RMSEA = 0.051), indicating that the model is acceptable in the face of a goodness-of-fit assessment. Overall, the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers played a vital role in reducing drought impacts and enhancing AC operations. The SEM suggested that adaptive capacity had a positive and significant impact on drought impacts, as it delivered values of β = 0.254 ***,

p = 0.000 < 0.001, and

t-value = 4.511 > 1.96. The participation in AC activities resulted in β = 0.106 **,

p = 0.04 < 0.05, and

t-value = 2.053 > 1.96. At the same time, the AC operation significantly impacted the adaptive capacity, resulting in values of β = 0.352 ***,

p =0.000 (

p < 0.001), and t-value = 6.957 (

t-value > 1.96). These factors also contributed to alleviating drought impacts, as can be seen in the values of β = 0.196 ***,

p = 0.000 < 0.001, and

t-value = 3.659. However, the participation in AC activities had no significant effects on AC operations, which resulted in values of β = −0.077,

p =0.122 > 0.05, and

t-value = −1.546 < 1.96. The results on the impacts of drought were β = 0.051,

p = 0.298 > 0.05, and

t-value = 1.1041 < 1.96.

In the rural communities of Cambodia, ACs were established to empower smallholder farmers to form groups to promote agricultural development and income generation activities. According to Heifer International Cambodia, NGOs have worked with government agencies and ACs to build capacity, infrastructure development, and marketing for agricultural products [Pers. Comm. K-2]. However, promoting agricultural development cannot be separated from disaster risk management, climate change adaptation, and resilience; in addition, flood and drought are the primary hazards affecting the livelihoods of smallholder farmers [Pers. Comm. K-1]. The participants in the consultative meeting agreed that AC operations did not directly impact drought risk management, but they did contribute to increasing the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers. For example, if smallholder farmers could maintain a high crop productivity and have good markets for their agricultural products, they would be able to invest more in their paddy fields [Pers. Comm. K-3]. The agricultural officer agreed that wealthy farmers had a better and stronger adaptive capacity, and they were less vulnerable to drought. Wealthier smallholder farmers could respond to drought impact in a timelier fashion; for example, they could pay for gasoline and pump machines to fill water into their paddy fields. Some wealthier farmers could also afford to pay for drip or sprinkler irrigation and a net to protect their crops and vegetables from water shortages and insects [Pers. Comm. K-1].

All the ACs were cooperating with government agencies and NGOs to raise awareness and to provide skills and techniques to reduce the impacts of drought to some extent. Smallholder farmers were mainly involved in raising awareness, skill development, marketing, and income generation activities through AC operation, and they were also beneficial in terms of reducing the impacts of drought [Pers. Comm. FGD 2]. The officer in the Bakan district administration described the limitation of ACs as due to the fact that they did not have sufficient financial and human resources to support smallholder farmers in order to reduce drought impacts [Pers. Comm. K-3]. The community meeting discussed the relationship between participation in AC activities, adaptive capacity, and drought impacts. The participants recognized the roles of ACs in increasing adaptive capacity and reducing drought impacts. They compared the smallholder farmers who participated in ACs and those who did not; however, they had different degrees of awareness and responses to drought impacts. They argued that smallholder farmers who were engaged in ACs could better solve the problems faced during droughts than those who were not engaged in ACs. Through field observations in the Bakan and Barsedth districts, the smallholder farmers who participated in ACs obtained knowledge and techniques from agricultural offers. At their house ground, the NGOs have also started experimenting with growing vegetables to be resilient to droughts and shortages of water. Smallholder farmers have gathered banana leaves around their vegetables in order to wet the soil such that the crops did not require much water to grow.