Collaborative Action and Social Organization in Remote Rural Regions: Autonomous Irrigation Arrangements in the Pamirs of Tajikistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory, Methods and Materials, and the Study Sites

2.1. The Nexus Medium Approach

2.2. Methodology and Materials

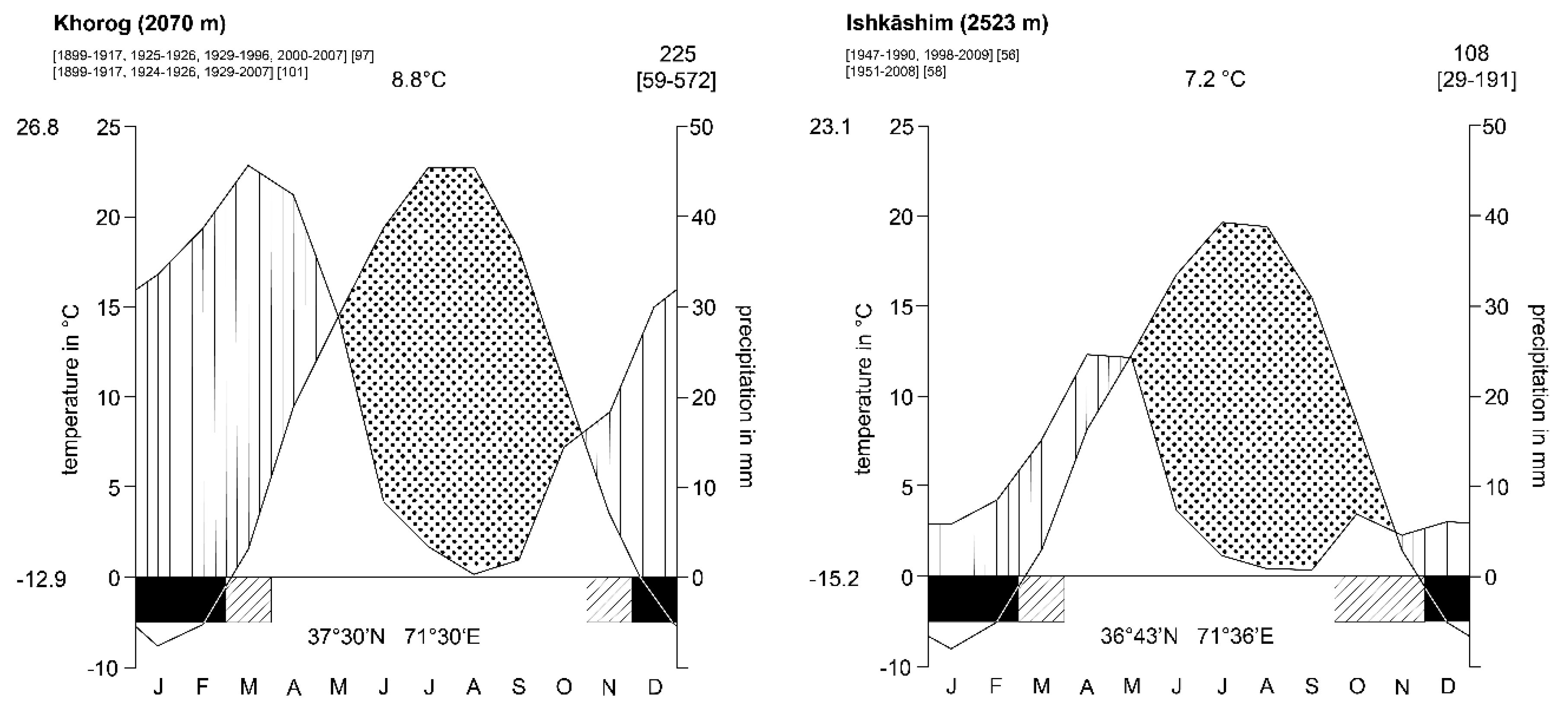

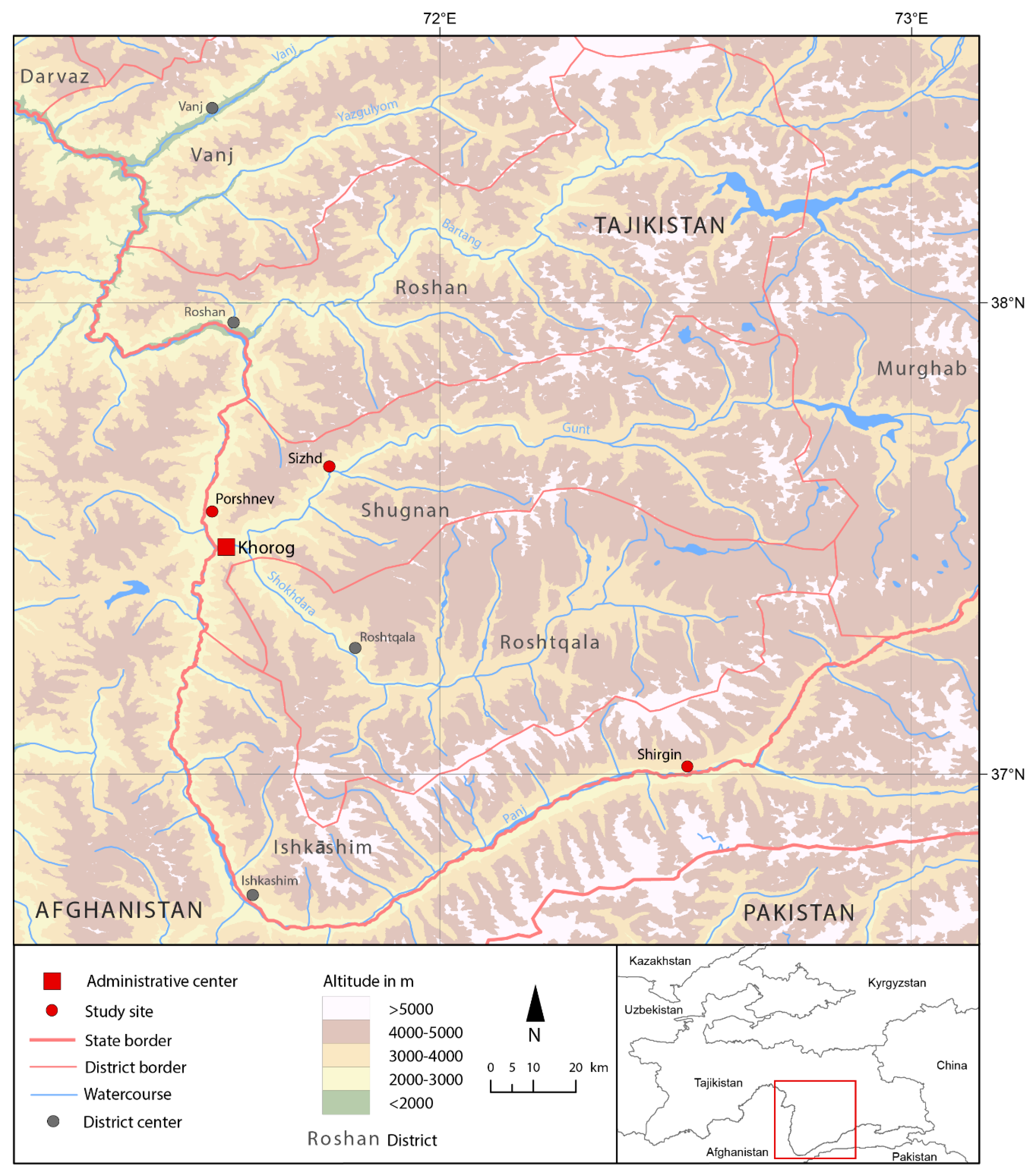

2.3. Three Study Sites in the Western Pamirs in Tajikistan

3. Results

3.1. Meanings Ascribed to Water by the Rural Communities

3.2. Autonomous Irrigation Arrangements of the Three Study Sites

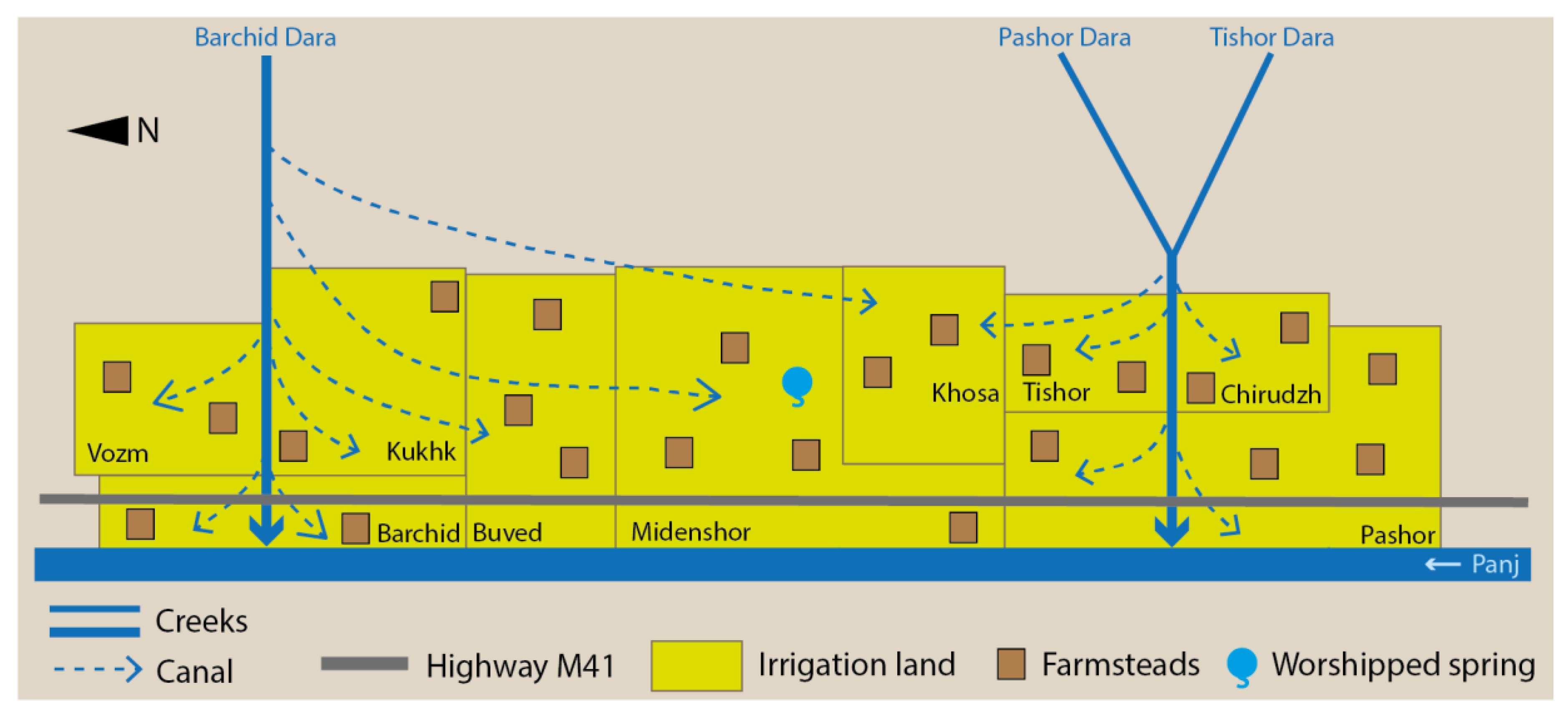

3.2.1. The Supralocal Water User Association of Porshnev Municipality

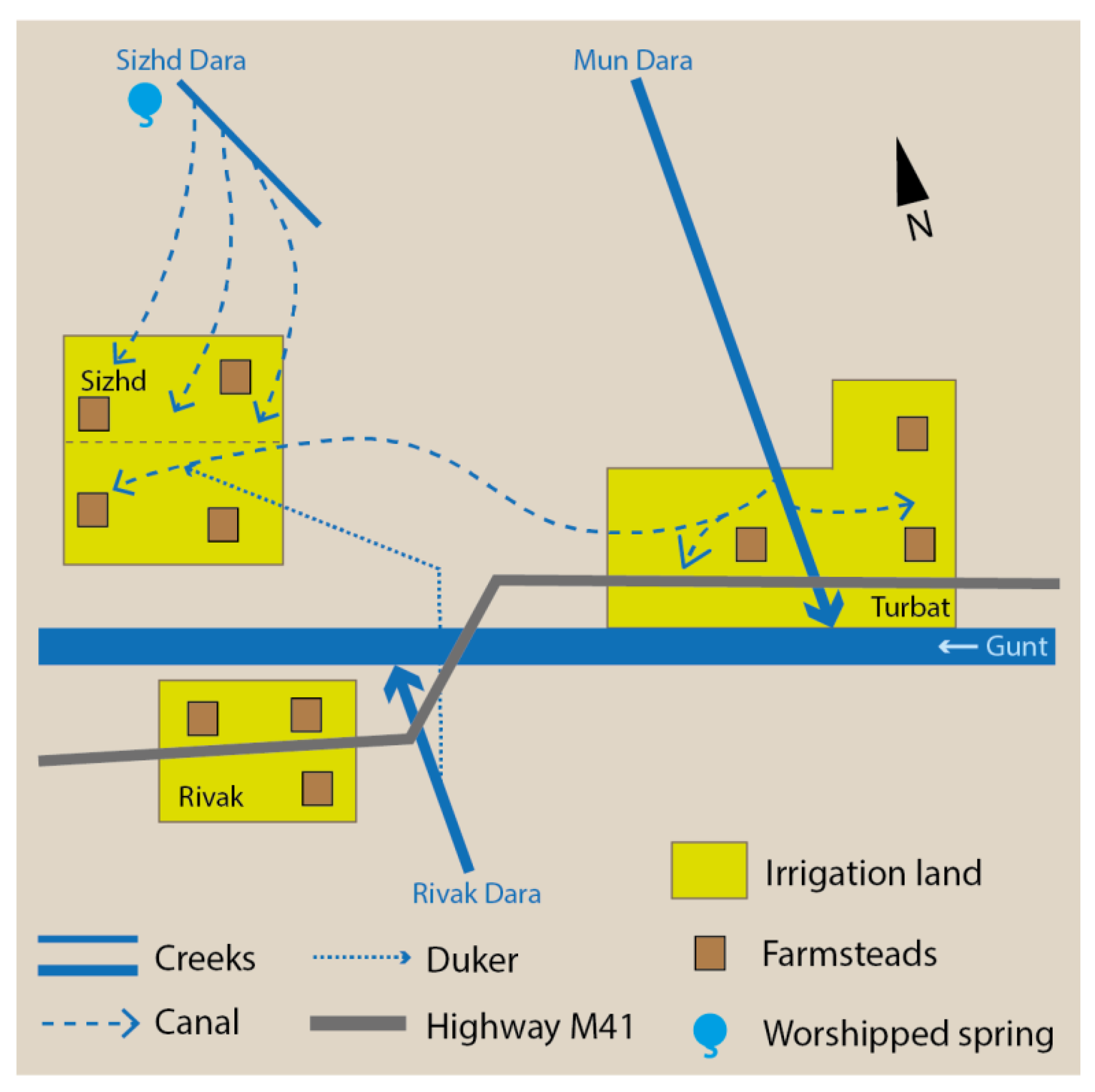

3.2.2. The Interlocal Irrigation Arrangement of Sizhd Village

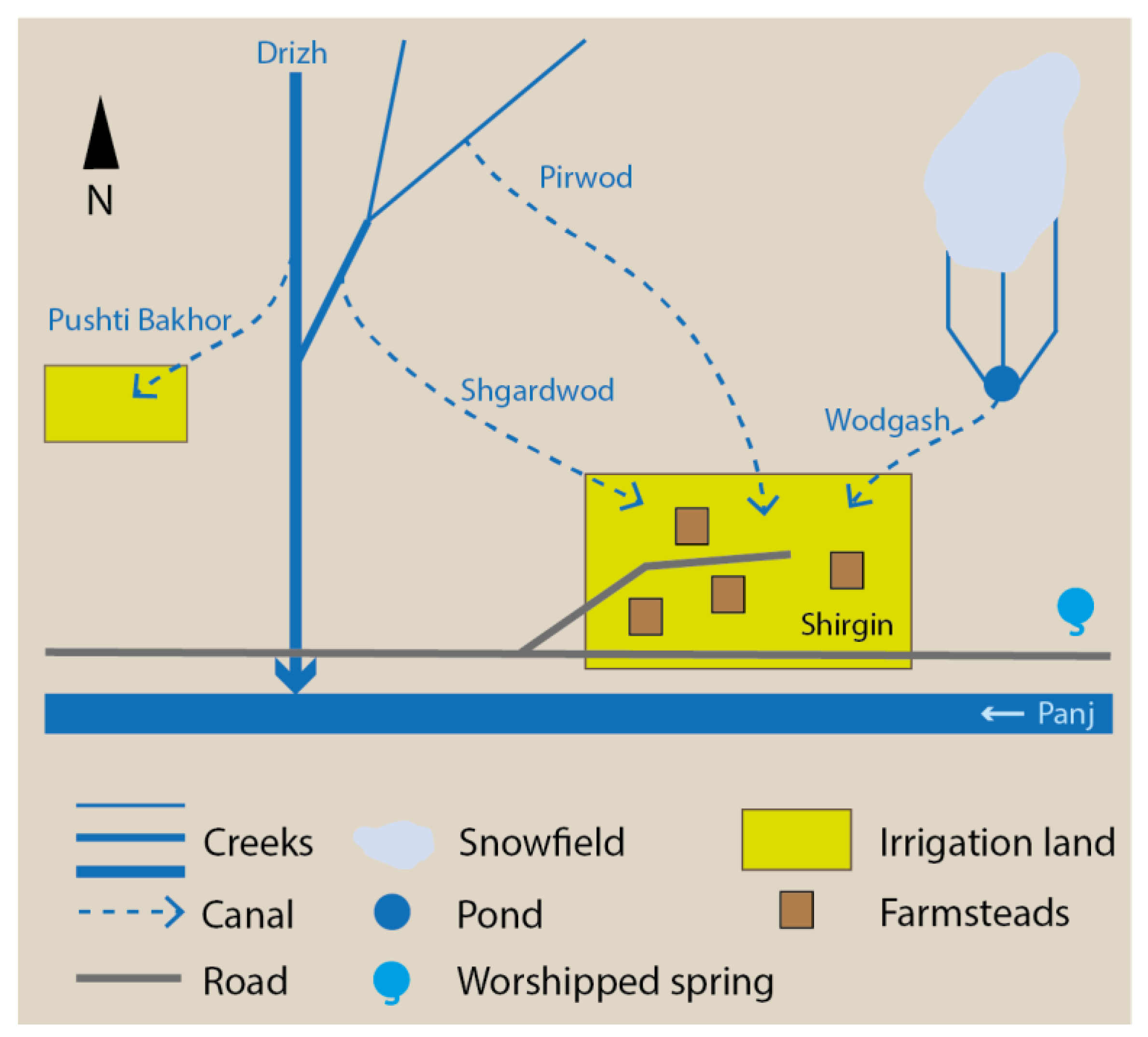

3.2.3. The Local Irrigation Arrangement of Shirgin Village

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bleischwitz, R.; Spataru, C.; VanDeveer, S.; Obersteiner, M.; van der Voet, E.; Johnson, C.; Andrews-Speed, P.; Boersma, T.; Hoff, H.; van Vuuren, D.P. Resource nexus perspectives towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizikova, L.; Roy, D.; Swanson, D.; Venema, H.D.; McCandless, M. The Water–Energy–Food Security Nexus: Towards a Practical Planning and Decision-Support Framework for Landscape Investment and Risk Management, 1st ed.; The International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nexus. Nexus in Central Asia. European Union Supports Investment to Foster Water, Energy and Food Security in Central Asia. Available online: https://www.water-energy-food.org/news/nexus-in-central-asia-european-union-supports-investment-to-foster-water-energy-and-food-security-in-central-asia/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Bazilian, M.; Rogner, H.; Howells, M.; Hermann, S.; Arent, D.; Gielen, D.; Steduto, P.; Mueller, A.; Komor, P.; Tol, R.S.J.; et al. Considering the Energy, Water and Food Nexus: Towards an Integrated Modelling Approach. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7896–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, K.; Pittock, J. The Energy-Water Nexus: Managing the Links between Energy and Water for a Sustainable Future. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, I.; Rakhmatullaev, S. Setting up the Agenda for Water Reforms in Central Asia: Does the Nexus Approach Help? Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, G.; Sharma, B. The Nexus Approach to Water–Energy–Food Security: An Option for Adaptation to Climate Change. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleischwitz, R.; Hoff, H.; Spataru, C.; van der Voet, E.; VanDeveer, S.D. (Eds.) The Resource Nexus. Preface and Introduction to the Routledge Handbook. In Routledge Handbook of the Resource Nexus, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Programme: Nexus—Water, Energy and Food Security for Bolivia. German Development Cooperation Supports the Integration and Systematic Implementation of Multi-Sectoral Development Measures; GIZ: La Paz, Bolivia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus. A New Approach in Support of Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture, 1st ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zahner, A.; Renewable Energy & Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP). Making the Case: How Agrifood Firms Are Building New Business Cases in the Water-Energy-Food Nexus, 1st ed.; REEEP, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Vienna, Austria; Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brears, R.C. (Ed.) The Green Economy and the Water-Energy-Food Nexus, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Church, M.; Mark, D.M. On Size and Scale in Geomorphology. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1980, 4, 342–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzmann, H. (Ed.) Water Towers of Humankind: Approaches and Perspectives for research on Hydraulic Resources in the Mountains of South and Central Asia. In Sharing Water. Irrigation and Water Management in the Hindukush, Karakoram, Himalaya, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Karachi, Pakistan, 2000; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fourniau, V. Some Notes on the Contribution of the Study of Irrigation to the History of Central Asia. In Sharing Water. Irrigation and Water Management in the Hindukush, Karakoram, Himalaya, 1st ed.; Kreutzmann, H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Karachi, Pakistan, 2000; pp. 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhiddinov, I. Zemledelie Pamirskikh Tadzhikov Vakhana i Ishkashima v XIX-Nachale XX v. (Istoriko-Etnograficheskii Ocherk), 1st ed.; Izd. Nauka; Glavnaya Redakciya Vostochnoi Literatury: Moskva, Soviet Union, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhiddinov, I. Osobennosti Tradicionnogo Zemledel’cheskogo Khozyaistva Pripamirskikh Narodnostei v XIX—Nachale XX Veka, 1st ed.; Izd. Nauka; Glavnaya Redakciya Vostochnoi Literatury: Moskva, Soviet Union, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Koen, B.D. Beyond the Roof of the World: Music, Prayer, and Healing in the Pamir Mountains, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Netting, R.M. The System Nobody Knows. Village Irrigation in the Swiss Alps. In Irrigation’s Impact on Society, 1st ed.; Downing, T.E., Gibson, M., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1974; pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzmann, H. (Ed.) Israr-ud-din. Social Organization and Irrigation Systems in the Khot Valley, Eastern Hindukush. In Sharing Water. Irrigation and Water Management in the Hindukush, Karakoram, Himalaya, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Karachi, Pakistan, 2000; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- WUA OU Water User Association Ob Umed. Informacionnyi Bulleten’ (Different Editions). Available online: http://obumed.org/index.php/publications (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Hajek, A.; Davis, A. Oral History. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 1st ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörre, A. Local Knowledge-Based Water Management and Irrigation in the Western Pamirs. Int. J. Environ. Impacts 2018, 1, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörre, A.; Goibnazarov, C. Small-Scale Irrigation Self-Governance in a Mountain Region of Tajikistan. Mt. Res. Dev. 2018, 38, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. (Ed.) Field Notes: How to Take Them, Code Them, Manage Them. In Research Methods in Anthropology. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th ed.; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA; New York, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada; Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 387–412. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, 1st ed.; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. (Ed.) Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture. In The Interpretation of Cultures, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Miehe, G.; Winiger, M.; Böhner, J.; Yili, Z. The Climatic Diagram Map of High Asia. Purpose and Concepts. Erdkunde 2001, 55, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenarios, S. Climate Change and Adaptation of Mountain Societies in Central Asia: Uncertainties, Knowledge Gaps, and Data Constraints. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 19, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Systems Analysis Group, UNH University of New Hampshire. Meteorological Station Data, Horog. 2010. Available online: http://neespi.sr.unh.edu/cgi-bin/station/meteo_station.pl?id=38954 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Water Systems Analysis Group, UNH University of New Hampshire. Meteorological Station Data, Ishkashim. 2010. Available online: http://neespi.sr.unh.edu/cgi-bin/station/meteo_station.pl?id=38957 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Jarvis, A.; Reuter, H.I.; Nelson, A.; Guevara, E. Hole-Filled Seamless Srtm Data V4. Tile 51–5. 2008. Available online: http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/ (accessed on 11 May 2015).

- OSM Open Street Map. Open Street Map. 2017. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 3 May 2017).

- Olufsen, O. Through the Unknown Pamirs. The Second Danish Pamir Expedition 1898–99, 1st ed.; William Heinemann: London, UK, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Andreev, M.S.; Polovcev, A.A. Materialy po Etnografii Iranskikh Plemen Srednei Azii. Ishkashim and Vakhan, 1st ed.; Tipografiya Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Saidov, M.; Ischuk, N. Natural Hazards in Tajikistan; OSCE: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2016.

- Kraudzun, T. From the Pamir Frontier to International Borders: Exchange Relations of the Borderland Population. In Subverting Borders. Doing Research on Smuggling and Small-Scale Trade, 1st ed.; Bruns, B., Miggelbrink, J., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; pp. 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzmann, H. Pamirian Crossroads. Kirghiz and Wakhi of High. Asia, 1st ed.; Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bossenbroek, L.; Zwarteveen, M. Irrigation Management in the Pamirs in Tajikistan: A Man’s Domain? Mt. Res. Dev. 2014, 34, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Pomfret, R. Consequences of Creating a Market. Economy. Evidence from Household Surveys in Central Asia, 1st ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dudwick, N.; Gomart, E.; Marc, A.; Kuehnast, K. (Eds.) From Soviet Expectations to Post-Soviet Realities: Poverty during the Transition. In When Things Fall Apart: Qualitative Studies of Poverty in the Former Soviet Union; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, F. Social and Economic Change in the Pamirs (Gorno-Badakhshan, Tajikistan), 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.; Guenther, T. Rural Livelihoods in Three Mountainous Regions of Tajikistan. Post-Communist Econ. 2007, 19, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrennikov, A.G. Ocherk Shugnana (S Kartoyu), 1895. In File 74/1/2; Archive of the Russian Geographical Society: St Petersburg, Russia, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Baranov, P.A. Pamir i Ego Zemledel’cheskoe Osvoenie, 1st ed.; Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel’stvo Kolkhoznoi i Sovkhoznoi Literatury: Moskva, Soviet Union, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Bubnova, M.A. Gorno-Badakhshanskaya Avtonomnaya Oblast’. Zapadnyi Pamir (Pamyatniki 2 tys. do n. e.—XIX v.), 1st ed.; Donish: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- GKTS Gosudarstvennyi Komitet Tadzhikskoi SSR po Statistike. Gorno-Badakhshanskaya Avtonomnaya Oblast‘ v Cifrakh v 1987 godu, 1st ed.; GOSKOMSTAT TaSSR: Dushanbe, Soviet Union, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers, H. Postsowjetische Transformation in Tadschikistan: Die Handlungsmacht der Akteure im Kontext von Landreform und Existenzsicherung, 1st ed.; Fränkische Geographische Gesellschaft: Erlangen, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- HSA PRT Head of the Statistical Agency under the President of the Republic of Tajikistan. Report on the Number of Households and Population in Rural Areas to 2015; HSA PRT: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2015.

- Parvonov, P. (Former clerk, state farm ‘Vatan’, Sizhd Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2014.

- Khudomunov, K. (Former water master, state farm ‘Vatan’, Sizhd Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2014.

- Snesarev, A.E. Statisticheskie Svedenie o Pravom Berege Reki Pyandzha v Uchastke Lyangar–Namadgut. In File 115/1/128; Archive of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences: St Petersburg, Russia, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- UNKhU Upravlenie Narodno-Khozyaistvennogo Uchyota Tadzhikskoi SSR, Sektor Uchyota Naseleniya i Kult’tury. Spisok Naselyonnykh Punktov TadzhSSR, 1st ed.; UNKhU: Stalinabad, Soviet Union, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Mudoyorov, K. (Former teacher; expert on local history, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2015, 2016.

- Deronov, S. (Teacher, farmer, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2016.

- ADC Austrian Development Cooperation; PAMIR Poverty Alleviation by Mitigation of Integrated High-Mountain Risk; FOCUS; Humanitarian Assistance, Hilfswerk Austria International. Nakshai Idorakunii Ofatkhoi Tabii. Dekhai Shirgin–Dzhamoati Vrang–Nokhiyai Ishkoshim; ADC: Khorog, Tajikistan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maklabekov, B. (Head of village, farmer, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2016.

- WUA OU Water User Association Ob Umed. Nasha Deyatel’nost’ v Cifrakh. 2018. Available online: http://obumed.org/index.php (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Khirzoev, M. (Former farm manager and water master state farm “Lenin”; water master,, Shirgin Village, affiliation, city, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2015, 2016.

- Mishkhonov, A. (Canal master, Sizhd Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2014.

- WUA OUA Administration of the Water User Association Ob Umed (Porshnev Municipality, Midenshor Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2018.

- Füssel, G.; Kaikovusova, G.; Schaddenhorst, H.; Sabzaliev, T. Understanding Community-Managed Hill Irrigation Systems in the Tajik Pamirs; Freie Universitaet Berlin, Centre for Development Studies: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhamedova, N.; Wegerich, K. The Feminization of Agriculture in Post-Soviet Tajikistan. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 57, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, Y. The Current Status of Lifestyle and Occupations in the Wakhan Area of Tajikistan. In Mapping Transitions in the Pamirs. Changing Human-Environmental Landscapes, 1st ed.; Kreutzmann, H., Watanabe, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Dodkhudoeva, L.; Yusufbekova, Z.; Shovalieva, M. National Festivals of the Tajiks Through the Ages, 1st ed.; University of Central Asia, Graduate School of Development, Cultural Heritage and Humanities Unit: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WUA OU Water User Association Ob Umed. Pervyi Poliv: Vozrozhdenie Tradicionnogo Prazdnika. Inf. Bull. 2017, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mamadnazarov, M.K.; Yakubov, Y.Y. Konstruktivnye i Funkcional’nye Osobennosti Gornobadakhshanskogo Stupenchatogo Potolka Chorkhona. In Pamirovedenie (Sbornik Statei). Vypusk 2, 1st ed.; Asimov, M.S., Ed.; Donish: Dushanbe, Soviet Union, 1985; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nekushoeva, S. The Conception of the House in the Shughni Linguistic Worldview, 1st ed.; University of Central Asia, Graduate School of Development, Cultural Heritage and Humanities Unit: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vasil’cov, K.S. Prirodnye Mesta Pokloneniya Zapadnogo Pamira. In Central’naya Aziya. Tradiciya v Usloviyakh Peremen, t. 3, 1st ed.; Rakhimov, R.R., Rezvan, M.E., Eds.; Kunstkamera: St. Peterburg, Russia, 2012; pp. 205–243. [Google Scholar]

- Beben, D. The Legendary Biographies of Nāsir-i Khusraw: Memory and Textualization in Early Modern Persian Ismā′īlism. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of History and Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khurshedov, J. (Local historian, Porshnev Municipality, Midenshor Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2018.

- Middleton, R. Legends of the Pamirs, 1st ed.; University of Central Asia: Khorog, Tajikistan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zarubin, I.I. Vypiski o Svyashhyonnykh Mestakh v Vakhane. In File 121/1/361; Archive of Oriental Manuscripts, Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Iloliev, A. King of Men: ’Ali ibn Abi Talib in Pamiri Folktales. J. Shi’a Islam. Stud. 2015, 8, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murodov, J. (Head of the village youth, farmer, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2018.

- Amonbekov, C. (Local guide, farmer, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2016.

- Omadbekov, M. (Elderly knowledgeable person, farmer, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2015.

- MSDSP Mountain Societies Development Support Programme. Tavsiyanoma Oidi Istifodabarii Samaranoki Zamin va Ob dar Dzhamoati Porshinevi Nokhiyai Shughnon, 1st ed.; MSDSP: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shabdolov, A. Incomplete Reforms and Institutional Bricolage in Community-Based Governance of Mountain Irrigation Systems in Tajikistan: A Case Study in the Pamirs, 1st ed.; Michael Succow Stiftung zum Schutz der Natur: Greifswald, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP United Nations Development Program. WUA “Ob Umed.” Tajikistan, 1st ed.; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yunonov, Q. (Expert for natural resource management, MSDSP Khorog, city, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2016, 2018.

- RT Republic of Tajikistan. Zakon Respubliki Tadzhikistan Ob Associacii Vodopol’zovatelei No 11. 2006. Available online: http://mmk.tj/ru/legislation/legislation-base/2006 (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- Freizer, S. Tajikistan. Local Self-Governance: A Potential Bridge between Government and Civil society? In Tajikistan at a Crossroad: The Politics of Decentralization, 1st ed.; De Martino, L., Ed.; Cimera: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Invarov, A. (Teacher, Shirgin Village, Tajikistan). Personal communication, 2015.

- Mirzo, O. Wakhan (A Scientific, Historic and Ethnographic Study), 1st ed.; Irfon: Khorog, Tajikistan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sehring, J. Irrigation reform in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2007, 21, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhav, R.; Xenarios, S.; Domullodzhanov, D. The Role of Water User Associations in Improving the Water for Energy Nexus in Tajikistan, 1st ed.; OSCE: Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenmark, M. Forward to the Future: A Conceptual Framework for Water Dependence. Ambio 1999, 28, 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Djumaboev, K.; Hamidov, A.; Anarbekov, O.; Gafurov, Z.; Tussupova, K. Impact of Institutional Change on Irrigation Management: A Case Study from Southern Uzbekistan. Water 2017, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasymov, U.; Hamidov, A. Comparative Analysis of Nature-Related Transactions and Governance Structures in Pasture Use and Irrigation Water in Central Asia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. The Role of Authority in the Collective Management of Hill Irrigation Systems in the Alai (Kyrgyzstan) and Pamir (Tajikistan). Mt. Res. Dev. 2013, 33, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year, Place | Institution: Professional or Social Status of Interviewee | Kind of Interview (Number of Interviews) | Gender of Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 Khorog Sizhd | Mountain Societies Development Support Programme (MSDSP): expert for natural resource management | Expert interview (1) | Male |

| Local administration: head of village | Narrative interview (1) | Male | |

| Water management: canal masters | Narrative interviews (3) | Male | |

| Former state farm “Vatan”: former employees (contemporary witnesses) | Narrative interviews (2) | Male | |

| Community members: household representatives | Semi-structured interviews (15) | Male | |

| 2015 Khorog Shirgin | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ): expert for rural development | Expert interviews (2) | Male |

| CAMP Tabiat: expert for natural resource management and regional history | Male | ||

| Community members: teacher, farmer, water master, and village elder | Narrative interviews (4) | Male | |

| 2016 Shirgin Khorog | Community members: teachers, farmers, shepherds, village elders, head of farmer organization, water master, amateur historians, religious dignitary, shop keeper, and head of the village youth | Narrative interviews (15) | Male |

| Former state farm “Lenin”: former employees (contemporary witnesses) | |||

| Local administration: head of village | Semi-structured interviews (2) | Male | |

| Community members: household representatives | Semi-structured interviews (12) | Male/Female | |

| MSDSP: expert for natural resource management | Expert interviews (2) | Male | |

| PEAS: agronomist, plant breeding expert | Male | ||

| 2018 Khorog Porshnev Shirgin | MSDSP: expert for natural resource management | Expert interviews (3) | Male |

| Pamir Experimental Agronomic Station of the Academy of Agricultural Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan (PEAS): agronomist, plant breeding expert | Male | ||

| University of Central Asia (UCA): agricultural scientist and expert on rural development | Male | ||

| Water User Association (WUA): head, deputy, water master, and clerk | Group interview (1) | Male | |

| Local administration: clerk | Male | ||

| Community members: head of farmer organization, local farmers | Male | ||

| Walk-in clinic: doctor, nurse | Semi-structured interview (1) | Female | |

| Local museum: historian | Narrative interview (1) | Male | |

| Community members: teacher, farmer, and head of the village youth | Semi-structured interviews (3) | Male |

| Porshnev Municipality | Sizhd Village | Shirgin Village | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 2000–2300 m | 2500–2600 m | 2800–3000 m |

| Inhabitants/households late 19th, early 20th century 1,2 | 283/59 | 77/8 | 110/11 |

| In 1931 3 | 1755/238 | 278/27 | 242/19 |

| In 2015 4 | 8568/1357 | 1024/153 | 893/103 |

| Main crops cultivated late 19th, early 20th century 1,2 | Grains and legumes | Grains and legumes | Grains and legumes |

| In the 1980s 5 | Forage crops and vegetables | Forage crops and vegetables | Forage crops and vegetables |

| In the 21st century 6 | Grains, legumes, root crops, and vegetables | Grains, legumes, root crops, and vegetables | Grains, legumes, root crops, and vegetables |

| Irrigation arrangement | |||

| Organizational status | Bottom–up initiated formal WUA | Informal local-specific arrangement | Informal local-specific arrangement |

| Spatio-administrative scale | Supralocal | Interlocal | Local |

| Number of beneficiaries 5,6,7 | ca. 9000 inhabitants (2018) | ca. 150 households (2014) | ca. 100 households (2016) |

| Key administrative tiers and functions 5,6 | Municipality administration, head of the WUA, water master, assembly of canal masters, individual canal masters, neighborhood groups, and individual households | VO and village assembly, canal masters, neighborhood groups, and individual households | VO and village assembly, water masters, heads of farmers, subgroups of farmers, and individual households |

| Funding and fees 5 | WUA membership fee of 1.00 TJS per household per month independent of the size of the irrigated area | A monthly fee of 15.00 TJS or 20.00 TJS from each beneficiary household dependent upon the location and the area of the irrigated land | A general annual remuneration of 10.00 TJS from each household to the water master independent of the size of the irrigated area |

| Main challenges besides scarcity and uneven distribution of irrigation water 5,6 | Lack of non-agricultural income opportunities Low wages Irrigation infrastructure vulnerable to natural hazards | Lack of non-agricultural income opportunities Low wages Growing number of farmers Water theft Irrigation infrastructure vulnerable to natural hazards | Lack of arable land and demographic growth Local of non-agricultural income opportunities Low wages Irrigation infrastructure vulnerable to natural hazards |

| May | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| Vozm/Buved | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Barchid/Midenshor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khosa/Kukhk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| June | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

| Vozm/Buved | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Barchid/Midenshor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khosa/Kukhk |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dörre, A. Collaborative Action and Social Organization in Remote Rural Regions: Autonomous Irrigation Arrangements in the Pamirs of Tajikistan. Water 2020, 12, 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12102905

Dörre A. Collaborative Action and Social Organization in Remote Rural Regions: Autonomous Irrigation Arrangements in the Pamirs of Tajikistan. Water. 2020; 12(10):2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12102905

Chicago/Turabian StyleDörre, Andrei. 2020. "Collaborative Action and Social Organization in Remote Rural Regions: Autonomous Irrigation Arrangements in the Pamirs of Tajikistan" Water 12, no. 10: 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12102905

APA StyleDörre, A. (2020). Collaborative Action and Social Organization in Remote Rural Regions: Autonomous Irrigation Arrangements in the Pamirs of Tajikistan. Water, 12(10), 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12102905