Complexity of Inheritance of Pathogenic Mutations Associated with Epilepsy in Consanguine Families from Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Subjects and DNA Collection

2.2. Exome Sequencing

2.3. Variant Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Case Reports

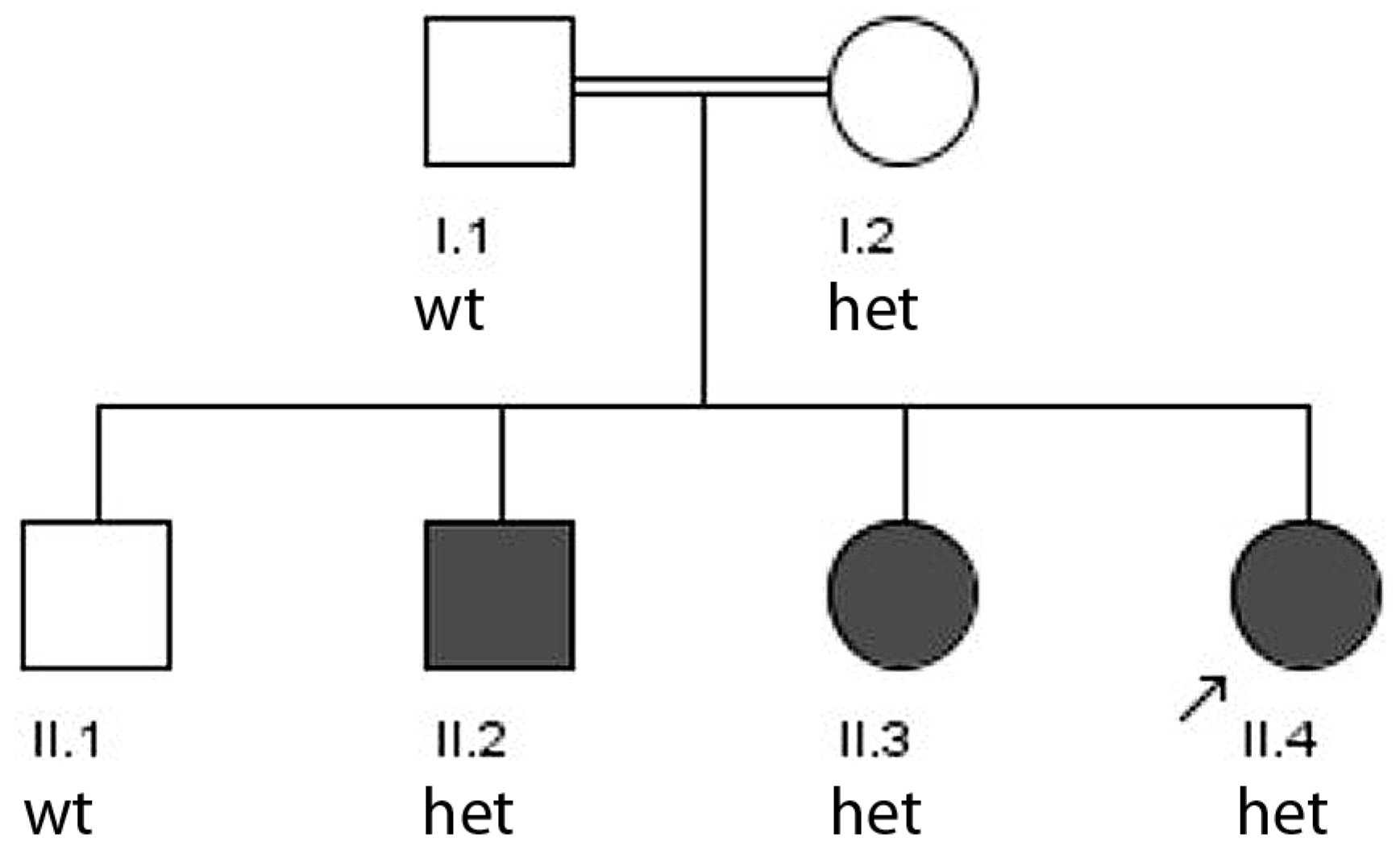

3.1.1. Family 1

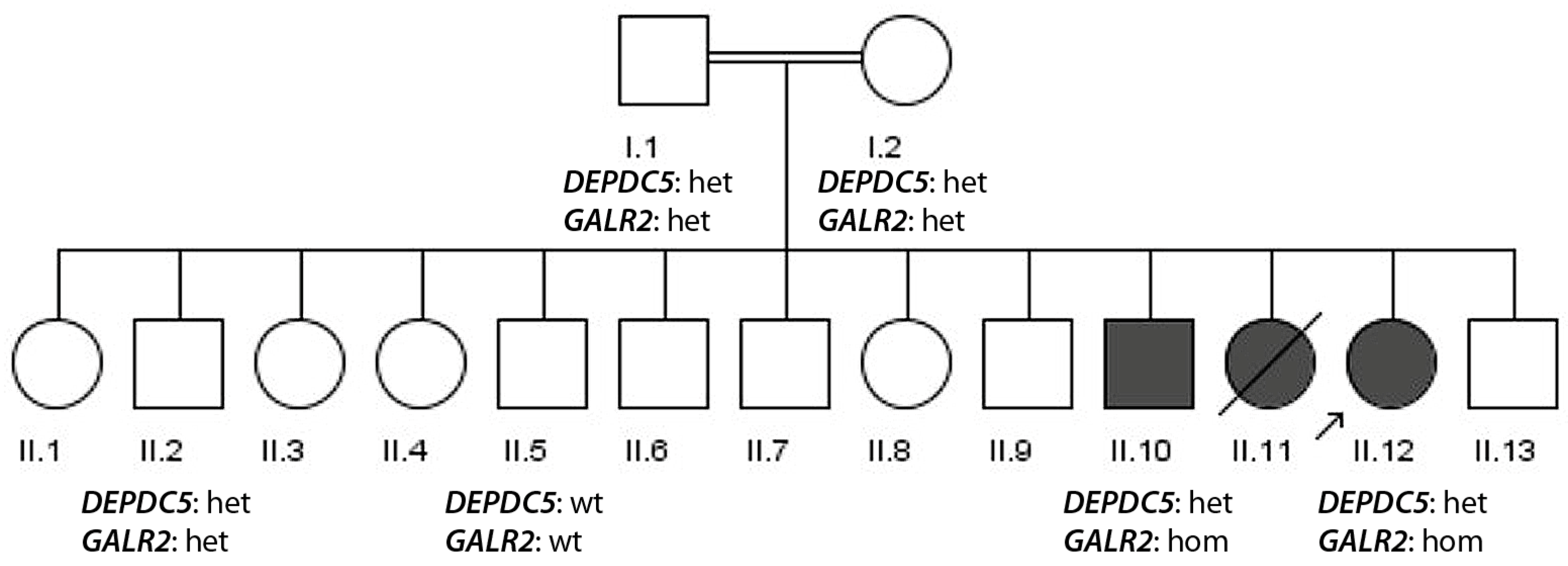

3.1.2. Family 2

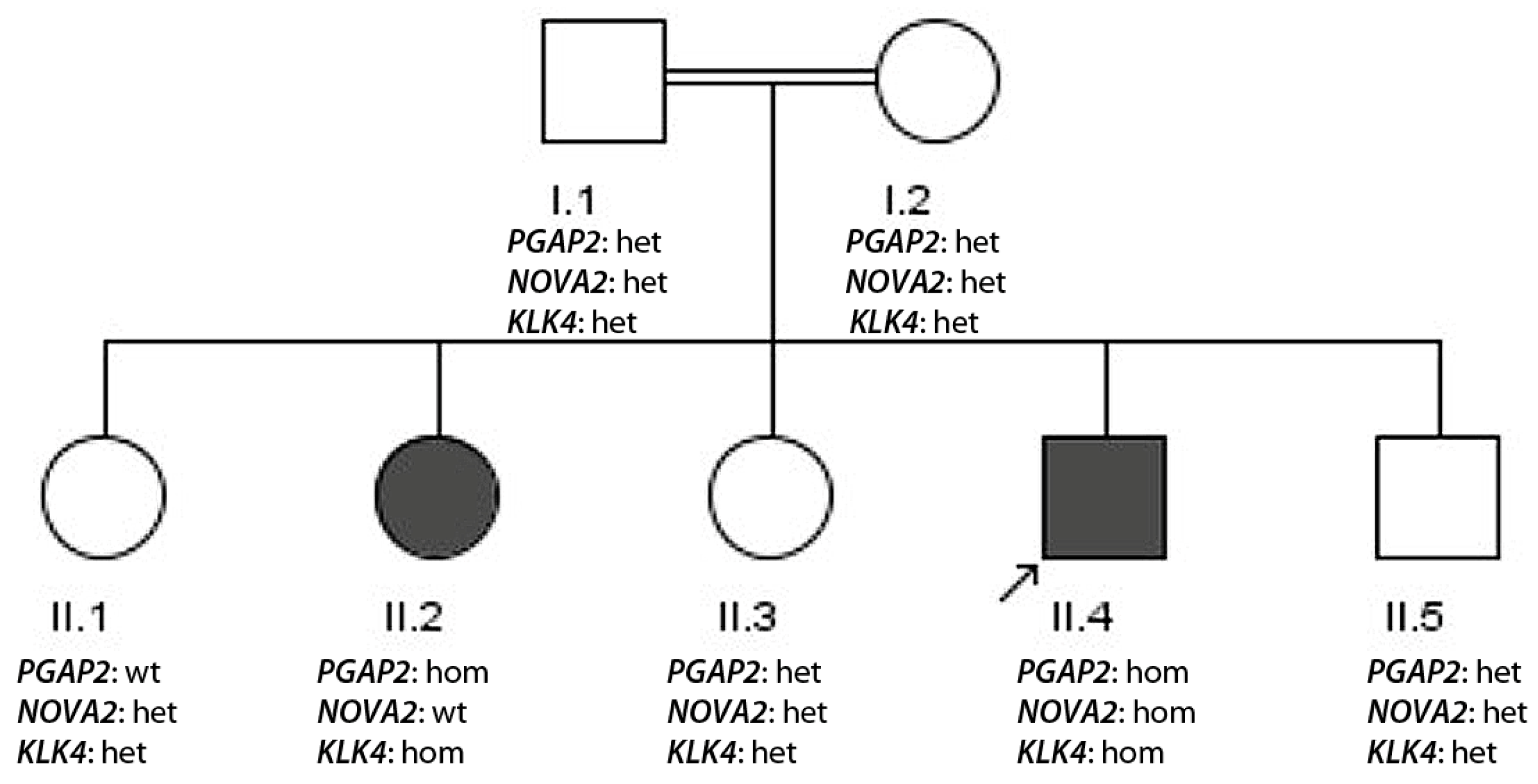

3.1.3. Family 3

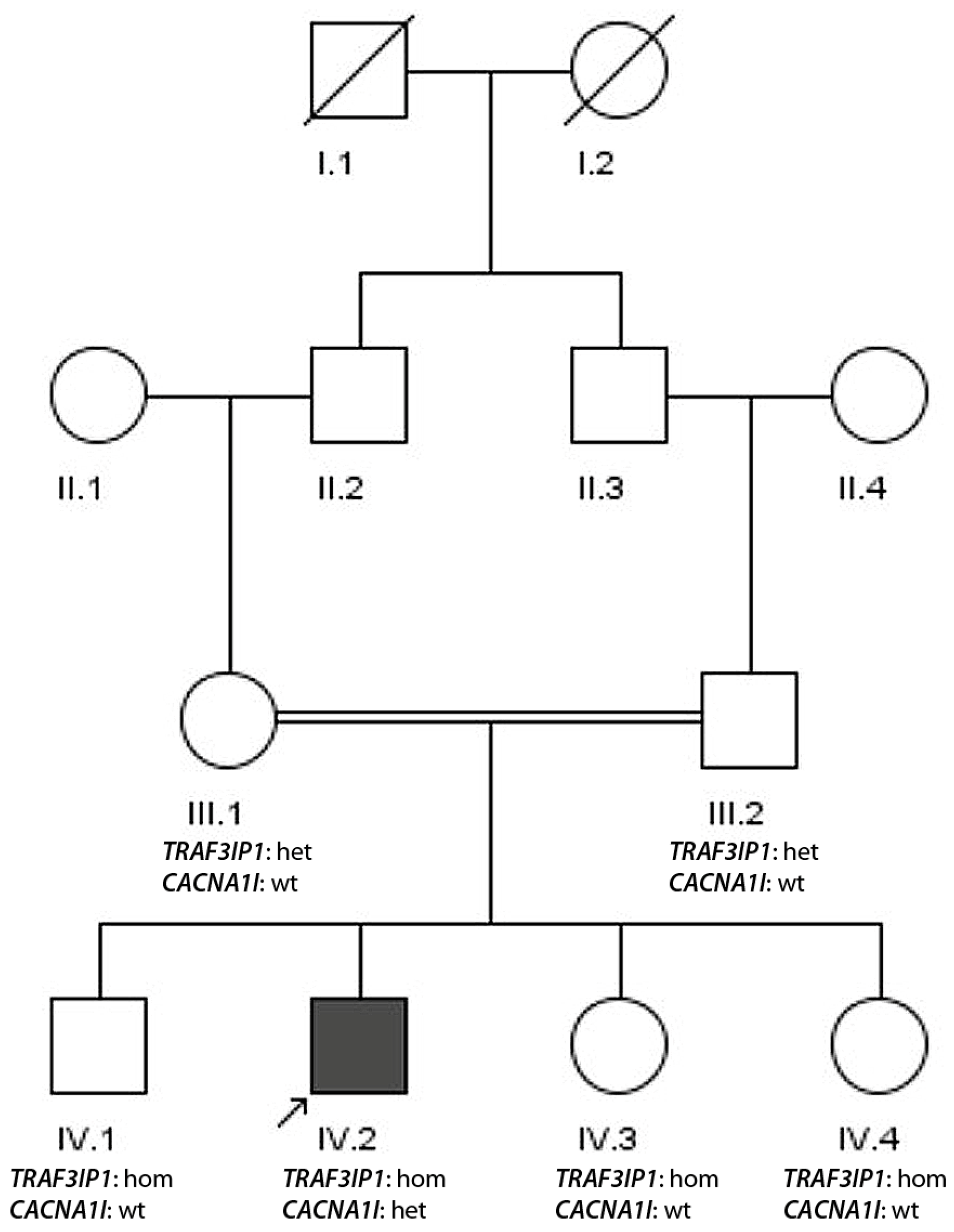

3.1.4. Family 4

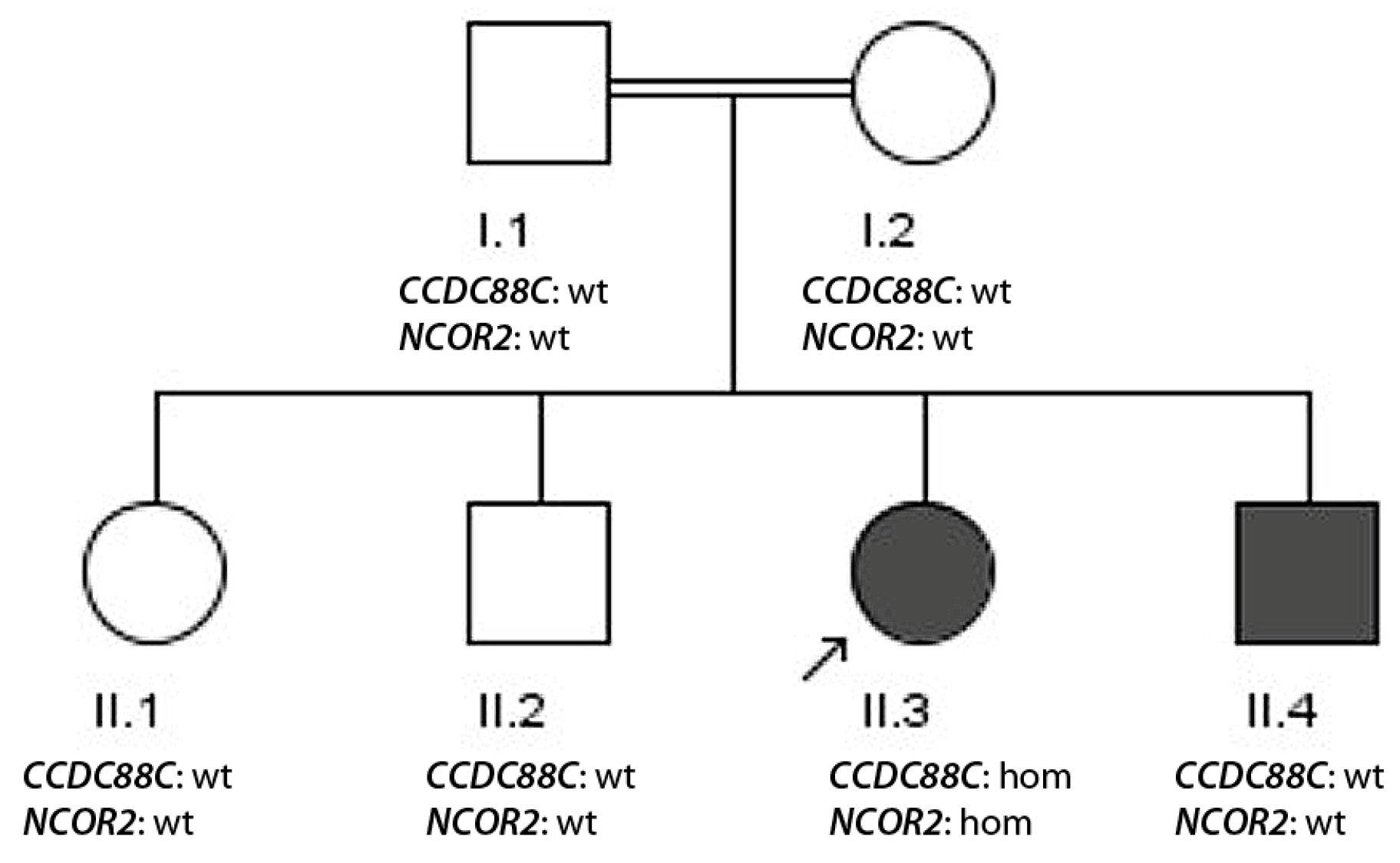

3.1.5. Family 5

4. Discussion

- (i)

- Dominant inheritance of a known epilepsy-associated mutation (family 1, TSC2).

- (ii)

- Simultaneous presence of a recessive variant and a dominant variant in epilepsy genes segregating with disease (family 2, GALR2 and DEPDC5).

- (iii)

- Multiple presence of recessive variants segregating with disease (family 3, PGAP2, KLK4 and NOVA2) in highly consanguine families.

- (iv)

- De novo appearance of a pathogenic epilepsy-associated mutation in a consanguine family (family 4, CACNA1I) in the additional presence of a homozygous pathogenic nonsense mutation in TRAF3IP1 not co-segregating with disease.

- (v)

- Missing segregation due to sample mismatch, which might generate problems in genetic counseling (family 5, CCDC88C).

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASM | Anti-seizure medication |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| ROH | Run of homozygosity |

References

- Perucca, P.; Bahlo, M.; Berkovic, S.F. The Genetics of Epilepsy. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2020, 21, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.L.; Scheffer, I.E.; Bennett, M.F.; Grinton, B.E.; Bahlo, M.; Berkovic, S.F. Genes4Epilepsy: An epilepsy gene resource. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, K.B.; Eggers, S.; Dalziel, K.; Riseley, J.; Mandelstam, S.; Myers, C.T.; McMahon, J.M.; Schneider, A.; Carvill, G.L.; Mefford, H.C.; et al. A population-based cost-effectiveness study of early genetic testing in severe epilepsies of infancy. Epilepsia 2018, 59, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, J.D.; McTague, A. Epilepsy and developmental disorders: Next generation sequencing in the clinic. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2020, 24, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, M.; Mefford, H.C. Recent advances in epilepsy genomics and genetic testing. F1000Research 2020, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibbens, L.M.; de Vries, B.; Donatello, S.; Heron, S.E.; Hodgson, B.L.; Chintawar, S.; Crompton, D.E.; Hughes, J.N.; Bellows, S.T.; Klein, K.M.; et al. Mutations in DEPDC5 cause familial focal epilepsy with variable foci. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, S.; Picard, F.; Rudolf, G.; Noe, E.; Achaz, G.; Thomas, P.; Genton, P.; Mundwiller, E.; Wolff, M.; Marescaux, C.; et al. Mutations of DEPDC5 cause autosomal dominant focal epilepsies. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Slegtenhorst, M.; de Hoogt, R.; Hermans, C.; Nellist, M.; Janssen, B.; Verhoef, S.; Lindhout, D.; van den Ouweland, A.; Halley, D.; Young, J.; et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 1997, 277, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, F.E.; Braams, O.; Vincken, K.L.; Algra, A.; Anbeek, P.; Jennekens-Schinkel, A.; Halley, D.; Zonnenberg, B.A.; van den Ouweland, A.; van Huffelen, A.C.; et al. Overlapping neurologic and cognitive phenotypes in patients with TSC1 or TSC2 mutations. Neurology 2008, 70, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricos, M.G.; Hodgson, B.L.; Pippucci, T.; Saidin, A.; Ong, Y.S.; Heron, S.E.; Licchetta, L.; Bisulli, F.; Bayly, M.A.; Hughes, J.; et al. Mutations in the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway regulators NPRL2 and NPRL3 cause focal epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, R.H.; Scheffer, I.E.; Barnett, S.; Richards, M.; Dibbens, L.; Desai, R.R.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Lev, D.; Mazarib, A.; Brand, N.; et al. Neuronal sodium-channel alpha-1-subunit mutations in generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcia, G.; Fleming, M.R.; Deligniere, A.; Gazula, V.-R.; Brown, M.R.; Langouet, M.; Chen, H.; Kronengold, J.; Abhyankar, A.; Cilio, R.; et al. De novo gain-of-function KCNT1 channel mutations cause malignant migrating partial seizures of infancy. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghaleb, Y.; Schneeberger, P.E.; Fernandez-Quintero, M.L.; Geisler, S.M.; Pelizzari, S.; Polstra, A.M.; van Hagen, J.M.; Denecke, J.; Campiglio, M.; Liedl, K.R.; et al. CACNA1I gain-of-function mutations differentially affect channel gating and cause neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain 2021, 144, 2092–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvill, G.L.; Weckhuysen, S.; McMahon, J.M.; Hartmann, C.; Moller, R.S.; Hjalgrim, H.; Cook, J.; Geraghty, E.; O’Roak, B.J.; Petrou, S.; et al. GABRA1 and STXBP1: Novel genetic causes of Dravet syndrome. Neurology 2014, 82, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Dykes, D.D.; Polesky, H.F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudin, A.P.; Baron, G.; Zsurka, G.; Hampel, K.G.; Elger, C.E.; Grote, A.; Weber, Y.G.; Lerche, H.; Thiele, H.; Nürnberg, P.; et al. Homozygous mutation in TXNRD1 is associated with genetic generalized epilepsy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 106, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varbank. Available online: https://varbank.ccg.uni-koeln.de/varbank2/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/65334/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Ochoa-Urrea, M.; Butler, E.A.; Bruenger, T.; Leu, C.; Boßelmann, C.M.; Najm, I.M.; Lhatoo, S.; Lal, D. Insights into DEPDC5-Related Epilepsy from 586 People: Variant Penetrance, Phenotypic Spectrum, and Treatment Outcomes. Neurology 2025, 105, e214235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinVar Record 50503. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/50503/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- ClinVar Record 288110. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/288110/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- ClinVar Record 852433. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/852433/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Freimann, K.; Kurrikoff, K.; Langel, Ü. Galanin receptors as a potential target for neurological disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2015, 19, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbari, N.F.; Kin, N.W.; Sharma, N.; Michaud, E.J.; Kesterson, R.A.; Yoder, B.K. Mutations in Traf3ip1 reveal defects in ciliogenesis, embryonic development, and altered cell size regulation. Dev. Biol. 2011, 360, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizet, A.A.; Becker-Heck, A.; Ryan, R.; Weber, K.; Filhol, E.; Krug, P.; Halbritter, J.; Delous, M.; Lasbennes, M.C.; Linghu, B.; et al. Mutations in TRAF3IP1/IFT54 reveal a new role for IFT proteins in microtubule stabilization. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarski, L.; Arbely, E. Translational read-through promotes aggregation and shapes stop codon identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 3747–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, S.M.; Howard, M.T. Processive selenocysteine incorporation during synthesis of eukaryotic selenoproteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 399, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drielsma, A.; Jalas, C.; Simonis, N.; Désir, J.; Simanovsky, N.; Pirson, I.; Elpeleg, O.; Abramowicz, M.; Edvardson, S. Two novel CCDC88C mutations confirm the role of DAPLE in autosomal recessive congenital hydrocephalus. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Seizure Type | Age of Onset | EEG Findings | Developmental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II.2 | tonic–clonic | 4 years | abnormal | cognitive impairment |

| II.3 | tonic–clonic | 5 years | abnormal | not able to speak |

| II.4 | tonic–clonic | 4 years | abnormal | not able to speak |

| Patient | Seizure Type | Age of Onset | EEG Findings | Developmental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II.10 | tonic–clonic | 3 years | abnormal | intellectual disability |

| II.11 | not known | <3 years | not known | deceased |

| II.12 | tonic–clonic | 5 years | normal | hyperactive |

| Patient | Seizure Type | Age of Onset | EEG Findings | Developmental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II.2 | tonic–clonic | 8 years | abnormal | non-syndromic |

| II.4 | tonic–clonic | 9 years | abnormal | intellectual disability |

| Patient | Seizure Type | Age of Onset | EEG Findings | Developmental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II.2 | tonic–clonic | 1 year | abnormal | intellectual disability |

| II.4 | tonic–clonic | 2 years | abnormal | intellectual disability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tahira, K.; Ullah, A.; Ullah, F.; Aziz, J.; Javed, M.I.; Kiyani, A.; Khanum, A.; Hallmann, K.; Baumgartner, T.; Surges, R.; et al. Complexity of Inheritance of Pathogenic Mutations Associated with Epilepsy in Consanguine Families from Pakistan. Genes 2026, 17, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020157

Tahira K, Ullah A, Ullah F, Aziz J, Javed MI, Kiyani A, Khanum A, Hallmann K, Baumgartner T, Surges R, et al. Complexity of Inheritance of Pathogenic Mutations Associated with Epilepsy in Consanguine Families from Pakistan. Genes. 2026; 17(2):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020157

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahira, Khajista, Anwar Ullah, Fazl Ullah, Jeena Aziz, Muhammad Ishaq Javed, Aasma Kiyani, Azra Khanum, Kerstin Hallmann, Tobias Baumgartner, Rainer Surges, and et al. 2026. "Complexity of Inheritance of Pathogenic Mutations Associated with Epilepsy in Consanguine Families from Pakistan" Genes 17, no. 2: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020157

APA StyleTahira, K., Ullah, A., Ullah, F., Aziz, J., Javed, M. I., Kiyani, A., Khanum, A., Hallmann, K., Baumgartner, T., Surges, R., Shaiq, P. A., & Kunz, W. S. (2026). Complexity of Inheritance of Pathogenic Mutations Associated with Epilepsy in Consanguine Families from Pakistan. Genes, 17(2), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020157