Surviving the Heat: Genetic Diversity and Adaptation in Sudanese Butana Cattle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Genotypic Data

2.2. Relationship Analysis

2.3. Diversity and Inbreeding Analyses

2.4. Signatures of Selection

2.5. Detection of Pathogens

3. Results

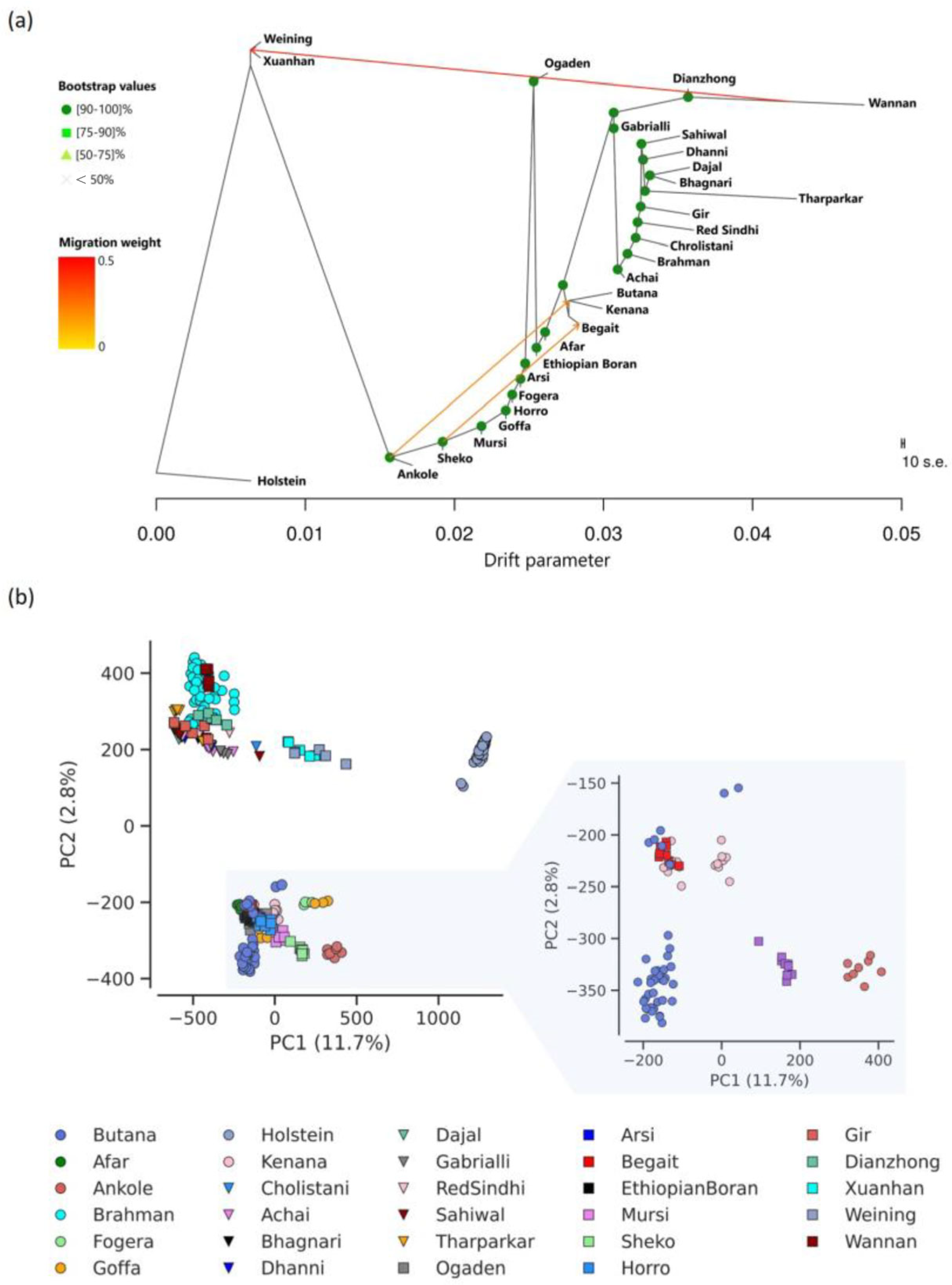

3.1. Relationship Among Indicine Cattle Breeds

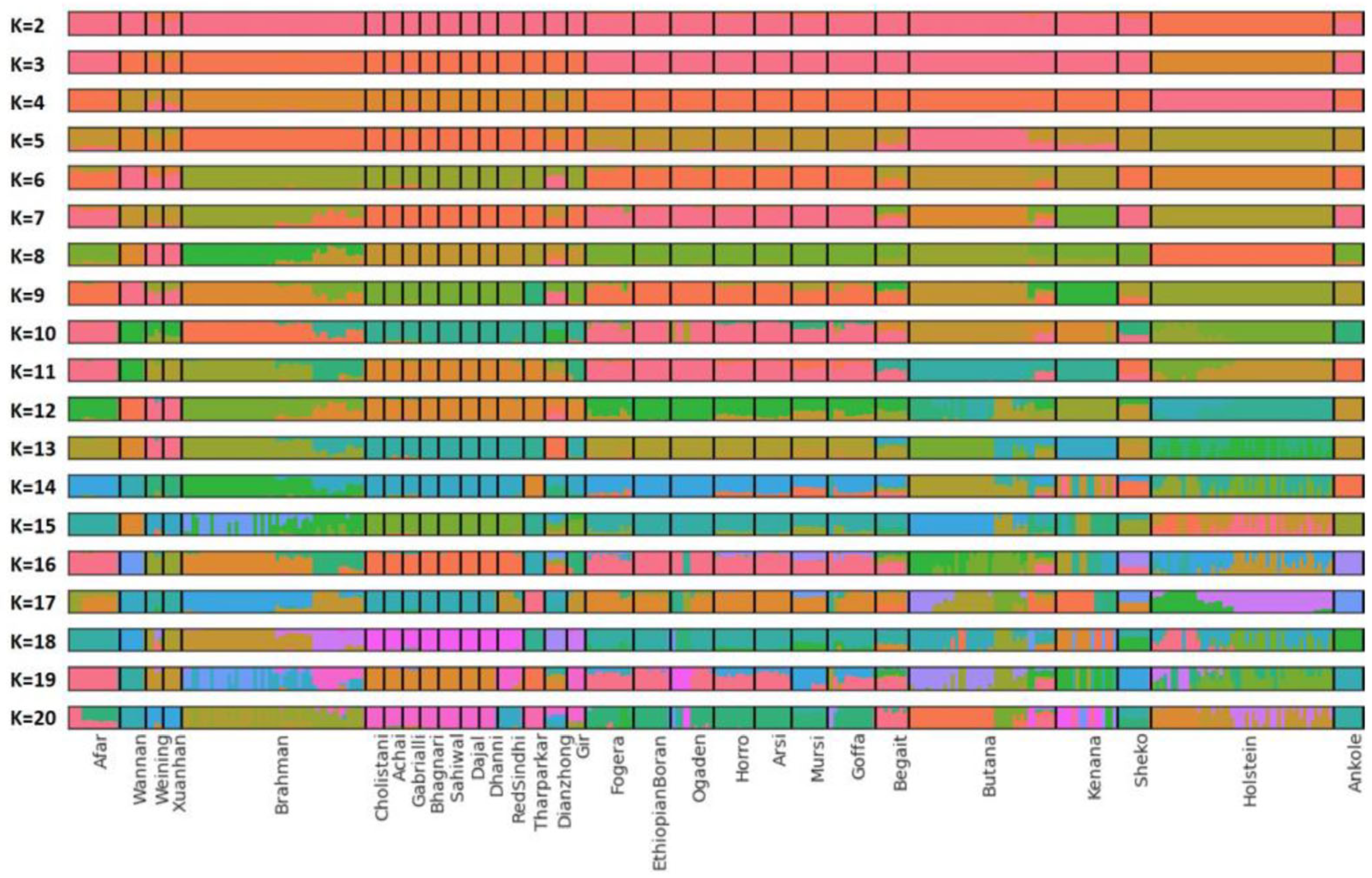

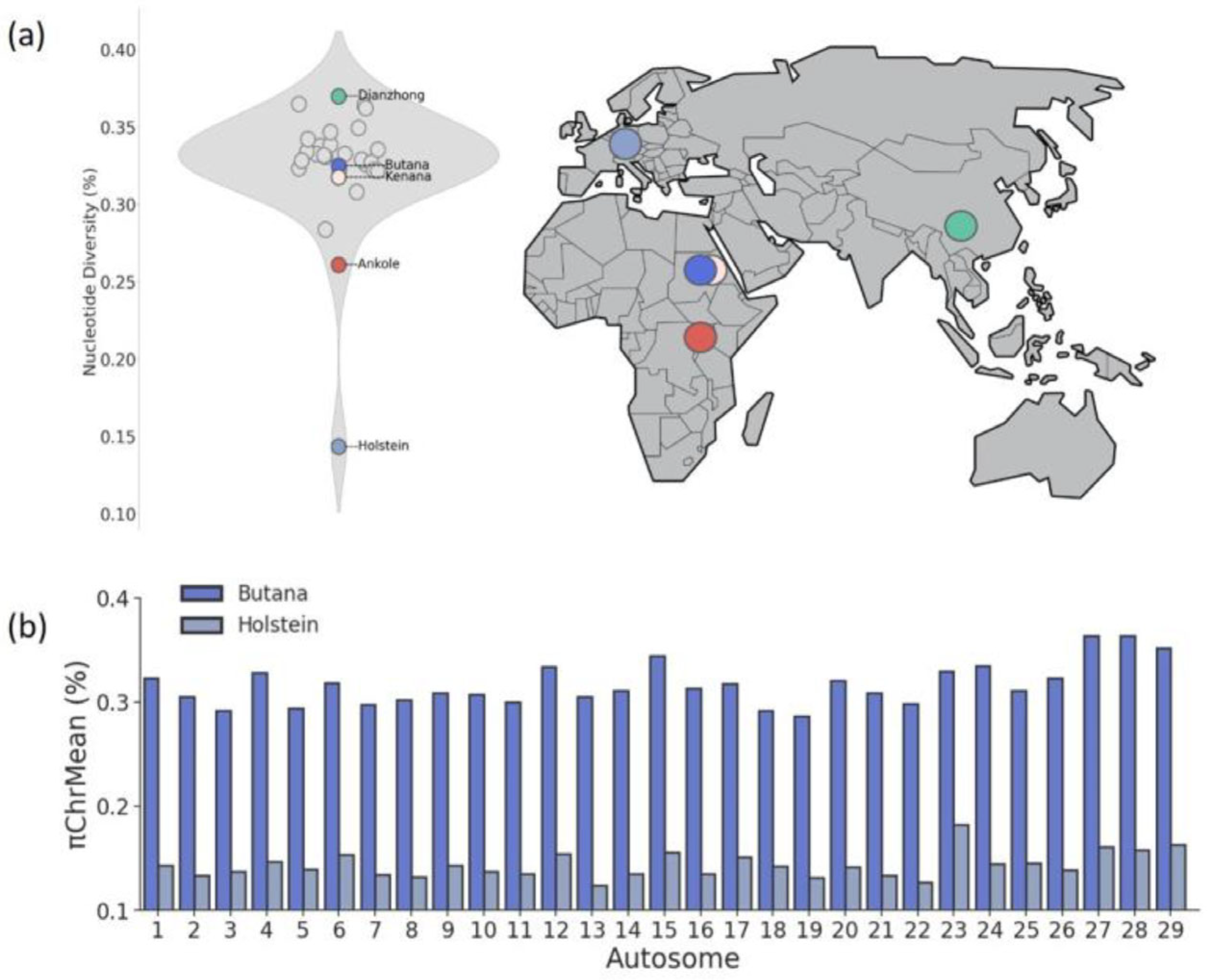

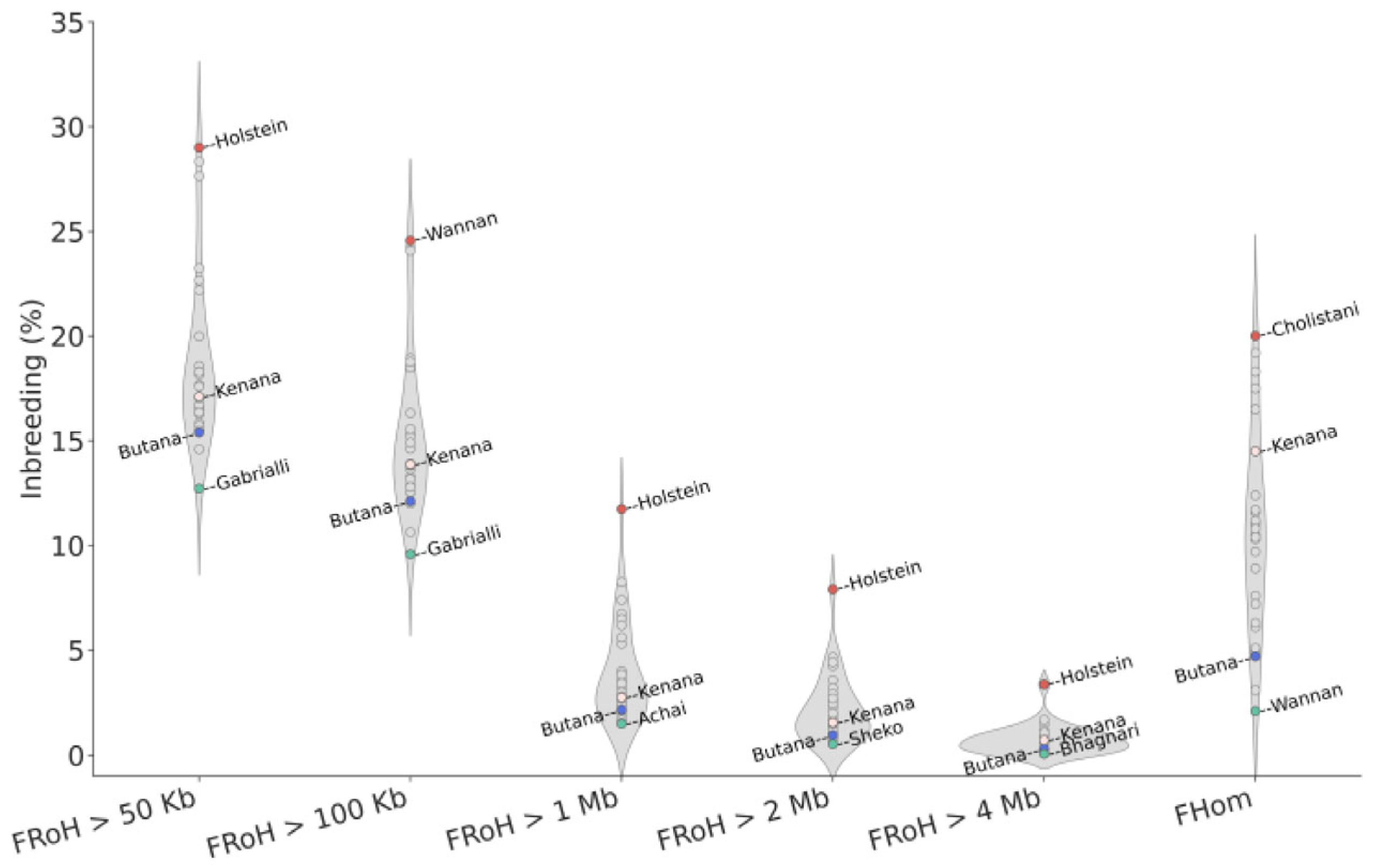

3.2. High Diversity and Low Inbreeding Detected in Butana Cattle

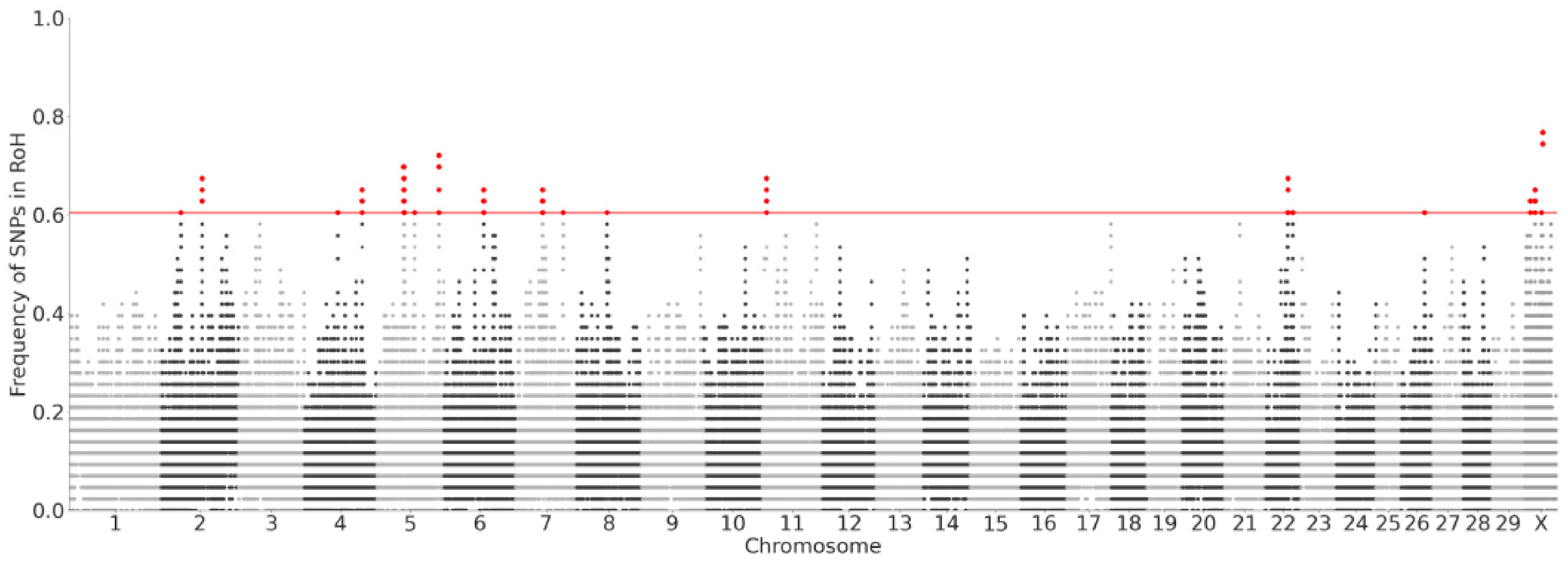

3.3. Butana’s Unique Variants May Hold Key to Heat Stress Adaptation and Immune Function

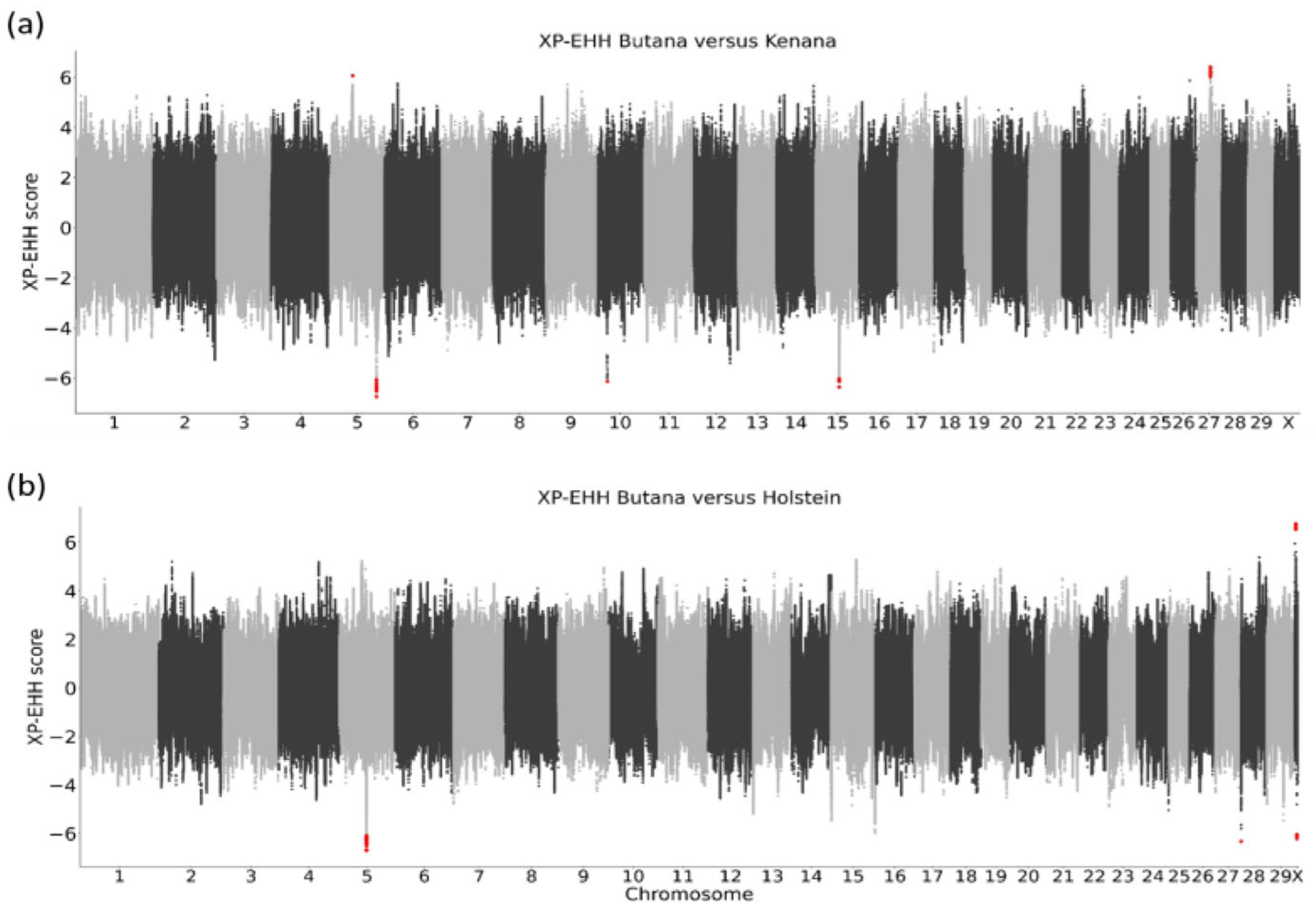

3.4. Signatures of Selection Indicate Potential Adaptation to Immune Response in Butana

3.5. Pathogen Responsible for Tropical Theileriosis Was Detected in Butana Cattle

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Affinity and Historical Introgression

4.2. Diversity and Inbreeding

4.3. Candidate Genes and Pathways for Heat Adaptation in Butana Cattle

4.4. Immune-Related Selection Signatures in Butana Cattle

4.5. Signatures of Selection Between Butana and Kenana Cattle

4.6. Signatures of Selection Between Butana and Holstein Cattle

4.7. Endemic Pathogens Detected in Butana Cattle

4.8. Breeding and Conservation Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahman, I.M.K. Sudanese Cattle Resources and Their Productivity—A Review. Agric. Rev. 2007, 28, 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Musam, M.-A.; Peters, K.J.; Ahmed, M.-K. On Farm Characterization of Butana and Kenana Cattle Breed Production Systems in Sudan. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288674640_On_farm_characterization_of_Butana_and_Kenana_cattle_breed_production_systems_in_Sudan (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Ageeb, A.; Hillers, J. Production and Reproduction Characteristics of Butana and Kenana Cattle of the Sudan. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/u1200t/u1200T0j.htm#production%20and%20reproduction%20characteristics%20of%20butana%20and%20kenana%20cattle%20of%20the%20s (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Loftus, R.; Cunningham, P. Molecular Genetic Analysis of African Zeboid Populations. In The Origins and Development of African Livestock; Blench, R., MacDonald, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 251–258. ISBN 9780203984239. [Google Scholar]

- Elzaki, S.; Korkuć, P.; Arends, D.; Reissmann, M.; Brockmann, G.A. Effects of DGAT1 on Milk Performance in Sudanese Butana × Holstein Crossbred Cattle. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, B.; Taha, K.M.; Hanotte, O.; Mwacharo, J.M. Historical Demographic Profiles and Genetic Variation of the East African Butana and Kenana Indigenous Dairy Zebu Cattle. Anim. Genet. 2014, 45, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reissmann, M.; Brockmnn, G.A.; Peters, K.J.; Musa, L.M. Genetic Characterization of the Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase Gene in Sudanese Kenana and Butana Cattle Breeds. Univ. Khartoum J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 16, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rosse, I.D.C.; Steinberg, R.D.S.; Coimbra, R.S.; Peixoto, M.G.C.D.; Verneque, R.S.; Machado, M.A.; Fonseca, C.G.; Carvalho, M.R.S. Novel SNPs and INDEL Polymorphisms in the 3′UTR of DGAT1 Gene: In Silico Analyses and a Possible Association. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 4555–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmatalla, S.A.; Reissmann, M.; Mueller, U.; Brockmann, G.A. Indentification of Genetic Variants Influencing Milk Production Traits in Sudanese Dairy Cattle. Res. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 9, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.S.; Rahmatalla, S.; Bortfeldt, R.; Arends, D.; Reissmann, M.; Brockmann, G.A. Milk Protein Polymorphisms and Casein Haplotypes in Butana Cattle. J. Appl. Genet. 2017, 58, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, L.; Riessmann, M.; Ishag, I. Characterization of the Growth Hormone Gene (GH1) in Sudanese Kenana and Butana Cattle Breeds. J. Anim. Prod. Adv. 2013, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, B.; Takeshima, S.N.; Nakao, R.; Moustafa, M.A.M.; Ahmed, M.K.A.; Kambal, S.; Mwacharo, J.M.; Alkhaibari, A.M.; Giovambattista, G. BoLA-DRB3 Gene Haplotypes Show Divergence in Native Sudanese Cattle from Taurine and Indicine Breeds. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzaki, S.; Korkuc, P.; Arends, D.; Reissmann, M.; Rahmatalla, S.A.; Brockmann, G.A. Validation of Somatic Cell Score-Associated SNPs from Holstein Cattle in Sudanese Butana and Butana × Holstein Crossbred Cattle. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahbahani, H.; Salim, B.; Almathen, F.; Al Enezi, F.; Mwacharo, J.M.; Hanotte, O. Signatures of Positive Selection in African Butana and Kenana Dairy Zebu Cattle. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hanotte, O.; Mwai, O.A.; Dessie, T.; Bashir, S.; Diallo, B.; Agaba, M.; Kim, K.; Kwak, W.; Sung, S.; et al. The Genome Landscape of Indigenous African Cattle. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geibel, J.; Reimer, C.; Weigend, S.; Weigend, A.; Pook, T.; Simianer, H. How Array Design Creates SNP Ascertainment Bias. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijjani, A.; Salim, B.; da Silva, M.V.B.; Eltahir, H.A.; Musa, T.H.; Marshall, K.; Hanotte, O.; Musa, H.H. Genomic Signatures for Drylands Adaptation at Gene-Rich Regions in African Zebu Cattle. Genomics 2022, 114, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B.J.; Daetwyler, H.D. 1000 Bull Genomes Project to Map Simple and Complex Genetic Traits in Cattle: Applications and Outcomes. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 7, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellott, D.W.; Hughes, J.F.; Skaletsky, H.; Brown, L.G.; Pyntikova, T.; Cho, T.J.; Koutseva, N.; Zaghlul, S.; Graves, T.; Rock, S.; et al. Mammalian y Chromosomes Retain Widely Expressed Dosage-Sensitive Regulators. Nature 2014, 508, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.D.; Bickhart, D.M.; Schnabel, R.D.; Koren, S.; Elsik, C.G.; Tseng, E.; Rowan, T.N.; Low, W.Y.; Zimin, A.; Couldrey, C.; et al. De Novo Assembly of the Cattle Reference Genome with Single-Molecule Sequencing. Gigascience 2020, 9, giaa021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.R.; Slatkint, M.; Maddison, W.P. Estimation of Levels of Gene Flow From DNA Sequence Data. Genetics 1992, 132, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, G.; Patterson, N.; Sankararaman, S.; Price, A.L. Estimating and Interpreting FST: The Impact of Rare Variants. Genome Res 2013, 23, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Rodrigues, M.F.; Ralph, P.; Harding, N.; Pisupati, R.; Rae, S. Cggh/Scikit-Allel, V1.3.1. bot, pyup.io bot. Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pickrell, J.K.; Pritchard, J.K. Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), version 3.6. Distributed by Author. Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. Available online: https://phylipweb.github.io/phylip/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Milanesi, M.; Capomaccio, S.; Vajana, E.; Bomba, L.; Garcia, J.F.; Ajmone-Marsan, P.; Colli, L. BITE: An R Package for Biodiversity Analyses. bioRxiv 2017. bioRxiv:181610. [Google Scholar]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the Number of Clusters of Individuals Using the Software Structure: A Simulation Study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitak, R.R. OptM: Estimating the Optimal Number of Migration Edges on Population Trees Using Treemix. Biol. Methods. Protoc. 2021, 6, bpab017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.S.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudvere, U.; Kolberg, L.; Kuzmin, I.; Arak, T.; Adler, P.; Peterson, H.; Vilo, J. G: Profiler: A Web Server for Functional Enrichment Analysis and Conversions of Gene Lists (2019 Update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W191–W198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The Variant Call Format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, V.; Danecek, P.; Scally, A.; Xue, Y.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Durbin, R. BCFtools/RoH: A Hidden Markov Model Approach for Detecting Autozygosity from next-Generation Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1749–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, P.C.; Varilly, P.; Fry, B.; Lohmueller, J.; Hostetter, E.; Cotsapas, C.; Xie, X.; Byrne, E.H.; McCarroll, S.A.; Gaudet, R.; et al. Genome-Wide Detection and Characterization of Positive Selection in Human Populations. Nature 2007, 449, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, M.; Klassmann, A.; Vitalis, R. Rehh 2.0: A Reimplementation of the R Package Rehh to Detect Positive Selection from Haplotype Structure. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, B.L.; Zhou, Y.; Browning, S.R. A One-Penny Imputed Genome from Next-Generation Reference Panels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, G.B.; Korkuć, P.; Reißmann, M.; Wolf, M.J.; May, K.; König, S.; Brockmann, G.A. Unmapped Short Reads from Whole-Genome Sequencing Indicate Potential Infectious Pathogens in German Black Pied Cattle. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Rincon, N.; Wood, D.E.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Pockrandt, C.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Steinegger, M. Metagenome Analysis Using the Kraken Software Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2815–2839. Erratum in: Nat Protoc. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01064-1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, J.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Thielen, P.; Salzberg, S.L. Bracken: Estimating Species Abundance in Metagenomics Data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017, 3, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, H.; Meng, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhou, F.; Wang, K.; Yang, Z.; Yang, C.; et al. Assessment of Adaptive Immune Responses of Dairy Cows with Burkholderia Contaminans-Induced Mastitis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1099623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.M.; Amin, W.F. Isolation of Burkholderia Cepacia Complex from Raw Miolk of Different Species of Dariy Animals in Assiut Governorate. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2012, 58, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanotte, O.; Bradley, D.G.; Ochieng, J.W.; Verjee, Y.; Hill, E.W.; Rege, J.E.O. African Pastoralism: Genetic Imprints of Origins and Migrations. Science 2002, 296, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, D.; Sevane, N.; Nicolazzi, E.L.; MacHugh, D.E.; Park, S.D.E.; Colli, L.; Martinez, R.; Bruford, M.W.; Orozco-terWengel, P. Domestication of Cattle: Two or Three Events? Evol. Appl. 2019, 12, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, G.B.; Korkuć, P.; Arends, D.; Wolf, M.J.; May, K.; König, S.; Brockmann, G.A. Genomic Diversity and Relationship Analyses of Endangered German Black Pied Cattle (DSN) to 68 Other Taurine Breeds Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 993959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiina, T.; Blancher, A.; Inoko, H.; Kulski, J.K. Comparative Genomics of the Human, Macaque and Mouse Major Histocompatibility Complex. Immunology 2017, 150, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Xie, G.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, A.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y. Convergent Genomic Signatures of Cashmere Traits: Evidence for Natural and Artificial Selection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Long, L.; Huang, X.; Tian, K.; Tian, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Z. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Genes Associated with Wool Fineness in Merinos. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Liang, H.; Zahoor Khan, M.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Chen, Y.; Xing, S.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, C. Comprehensive Transcriptomic Analysis Unveils the Interplay of MRNA and LncRNA Expression in Shaping Collagen Organization and Skin Development in Dezhou Donkeys. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1335591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harazin, M.; Parwez, Q.; Petrasch-Parwez, E.; Epplen, J.T.; Arinir, U.; Hoffjan, S.; Stemmler, S. Variation in the COL29A1 Gene in German Patients with Atopic Dermatitis, Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Dermatol. 2010, 37, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, A.; Söderhäll, C.; Fölster-Holst, R.; Baurecht, H.; Harde, V.; Müller-Wehling, K.; Rodríguez, E.; Ruether, A.; Franke, A.; Wagenpfeil, S.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of the COL29A1 Gene Does Not Support a Role in Eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 1187–1194.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderhäll, C.; Marenholz, I.; Kerscher, T.; Rüschendorf, F.; Esparza-Gordillo, J.; Worm, M.; Gruber, C.; Mayr, G.; Albrecht, M.; Rohde, K.; et al. Variants in a Novel Epidermal Collagen Gene (COL29A1) Are Associated with Atopic Dermatitis. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkrans, C.; Banks, A.; Reiter, S.; Looper, M. Calving Traits of Crossbred Brahman Cows Are Associated with Heat Shock Protein 70 Genetic Polymorphisms. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 119, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.S.; Rocha-Frigoni, N.A.S.; Mingoti, G.Z.; Roth, Z.; Hansen, P.J. Modification of Embryonic Resistance to Heat Shock in Cattle by Melatonin and Genetic Variation in HSPA1L. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9152–9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiricò, L.; Morera, P.; Primi, V.; Lacetera, N.; Nardone, A.; Bernabucci, U. Cellular Thermotolerance Is Associated with Heat Shock Protein 70.1 Genetic Polymorphisms in Holstein Lactating Cows. Cell Stress Chaperones 2011, 16, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, P.J. Prospects for Gene Introgression or Gene Editing as a Strategy for Reduction of the Impact of Heat Stress on Production and Reproduction in Cattle. Theriogenology 2020, 154, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropka-Molik, K.; Zukowski, K.; Eckert, R.; Gurgul, A.; Piõrkowska, K.; Oczkowicz, M. Comprehensive Analysis of the Whole Transcriptomes from Two Different Pig Breeds Using RNA-Seq Method. Anim. Genet. 2014, 45, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, D.; Wenhui, J.I.; Xiong, X.; Liang, Q.; Yao, W.; Mipam, T.D.; Zhong, J.; Jian, L.I. Population Genome of the Newly Discovered Jinchuan Yak to Understand Its Adaptive Evolution in Extreme Environments and Generation Mechanism of the Multirib Trait. Integr. Zool. 2021, 16, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özmen, Ö.; Karaman, K. Transcriptome Analysis and Potential Mechanisms of Bovine Oocytes under Seasonal Heat Stress. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 1179–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravastrand, C.; Yurchenko, M.; Kristensen, S.; Skjesol, A.; Chen, C.; Iqbal, Z.; Dahlen, K.R.; Nonstad, U.; Ryan, L.; Espevik, T.; et al. Rab11FIP2 Controls NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation through Rab11b. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2025.05.19.654879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedl, M.; Zheng, S.; Abraham, C. The IL18RAP Region Disease Polymorphism Decreases IL-18RAP/IL-18R1/IL-1R1 Expression and Signaling through Innate Receptor–Initiated Pathways. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 5924–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Barquero, V.; de Marco, G.; Martínez-Hervas, S.; Adam-Felici, V.; Pérez-Soriano, C.; Gonzalez-Albert, V.; Rojo, G.; Ascaso, J.F.; Real, J.T.; Garcia-Garcia, A.B.; et al. Are IL18RAP Gene Polymorphisms Associated with Body Mass Regulation? A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, S.; Jonuleit, H.; Schmitt, E.; Müller, G.; Yamauchi, H.; Kurimoto, M.; Knop, J.; Enk, A.H. Production of Functional IL-18 by Different Subtypes of Murine and Human Dendritic Cells (DC): DC-Derived IL-18 Enhances IL-12-Dependent Th1 Development. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998, 28, 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freihat, L.A.; Wheeler, J.I.; Wong, A.; Turek, I.; Manallack, D.T.; Irving, H.R. IRAK3 Modulates Downstream Innate Immune Signalling through Its Guanylate Cyclase Activity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Rahman, A.H.; Hassan, M.A.; Salih, S.E.M.; Paone, M.; Cecchi, G. An Atlas of Tsetse and Bovine Trypanosomosis in Sudan. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Singh, S.; Ganguly, I.; Bhatia, A.K.; Bharti, V.K.; Dixit, S.P. Genome-Wide Diversity Analysis for Signatures of Selection of Bos Indicus Adaptability under Extreme Agro-Climatic Conditions of Temperate and Tropical Ecosystems. Anim. Gene 2021, 20, 200115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, S.; Yao, K.; Ren, S.; Cheng, P.; Qu, M.; Ma, X.; Gao, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Lumpy Skin Disease Virus ORF127 Protein Suppresses Type I Interferon Responses by Inhibiting K63-Linked Ubiquitination of Tank Binding Kinase 1. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Ren, S.; Rehman, Z.U.; Wang, X.; Yin, X.; Sun, Y.; Wan, X.; Chen, H. Molecular Characterization, Expression, and Functional Identification of TANK-Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1) of the Cow (Bos Taurus) and Goat (Capra Hircus). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2022, 133, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorano, A.M.; Cardoso, D.F.; Carvalheiro, R.; Júnior, G.A.F.; de Albuquerque, L.G.; de Oliveira, H.N. Signatures of Selection in Nelore Cattle Revealed by Whole-Genome Sequencing Data. Genomics 2022, 114, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liang, R.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Sun, D.; Li, J. Identification of Candidate Genes for Milk Production Traits by RNA Sequencing on Bovine Liver at Different Lactation Stages. BMC Genet. 2020, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkuć, P.; Neumann, G.B.; Hesse, D.; Arends, D.; Reißmann, M.; Rahmatalla, S.; May, K.; Wolf, M.J.; König, S.; Brockmann, G.A. Whole-Genome Sequencing Data Reveal New Loci Affecting Milk Production in German Black Pied Cattle (DSN). Genes 2023, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Miki, Y.; Ibi, T.; Wakaguri, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Sugimoto, Y.; Suzuki, Y. A 44-Kb Deleted-Type Copy Number Variation Is Associated with Decreasing Complement Component Activity and Calf Mortality in Japanese Black Cattle. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieffer, K.M.; Emrich, S.M.; Yochum, G.S.; Koltun, W.A. CD163L1+CXCL10+ Macrophages Are Enriched Within Colonic Lamina Propria of Diverticulitis Patients. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 267, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cara, F.; Rachubinski, R.A.; Simmonds, A.J. Distinct Roles for Peroxisomal Targeting Signal Receptors Pex5 and Pex7 in Drosophila. Genetics 2019, 211, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cara, F.; Sheshachalam, A.; Braverman, N.E.; Rachubinski, R.A.; Simmonds, A.J. Peroxisome-Mediated Metabolism Is Required for Immune Response to Microbial Infection. Immunity 2017, 47, 93–106.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelley, T.K.; Degnan, K.; Longhi, C.W.; Morrison, W.I. Genomic Analysis Offers Insights into the Evolution of the Bovine TRA/TRD Locus. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niimura, Y.; Matsui, A.; Touhara, K. Extreme Expansion of the Olfactory Receptor Gene Repertoire in African Elephants and Evolutionary Dynamics of Orthologous Gene Groups in 13 Placental Mammals. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, P.J.; Bautista, J.M.; Gilsanz, F. G6PD Deficiency: The Genotype-Phenotype Association. Blood Rev. 2007, 21, 267–283, Corrigendum in Blood Rev. 2007, 21, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y.; Guan, Y.; Yang, J. FAM3 Gene Family: A Promising Therapeutical Target for NAFLD and Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolism 2018, 81, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Jia, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Chi, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, G.; Guan, Y.; Yang, J. FAM3A Is a Target Gene of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 4160–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro da Silva, T.; Polli, J.E.; Swaan, P.W. The Solute Carrier Family 10 (SLC10): Beyond Bile Acid Transport. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towers, R.E.; Murgiano, L.; Millar, D.S.; Glen, E.; Topf, A.; Jagannathan, V.; Drögemüller, C.; Goodship, J.A.; Clarke, A.J.; Leeb, T. A Nonsense Mutation in the IKBKG Gene in Mares with Incontinentia Pigmenti. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, M.L.; Scheidt, J.L.; Rhodes, J.L.; Henthorn, P.S.; Werner, P. Mutation Identification in a Canine Model of X-Linked Ectodermal Dysplasia. Mamm. Genome 2005, 16, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hur, S.W.; Jeong, B.C.; Oh, S.H.; Hwang, Y.C.; Kim, S.H.; Koh, J.T. The Fam50a Positively Regulates Ameloblast Differentiation via Interacting with Runx2. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, D.W.; Choi, T.-I.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lee, K.-H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, C.-H. Using Zebrafish as an Animal Model for Studying Rare Neurological Disorders: A Human Genetics Perspective. J. Genet. Med. 2024, 21, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, S.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; McConkey, H.; Balci, T.; Siu, V.M.; Skinner, C.D.; Stevenson, R.E.; Sadikovic, B.; et al. Detection of a DNA Methylation Signature for the Intellectual Developmental Disorder, X-Linked, Syndromic, Armfield Type. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotan, L.D.; Ternier, G.; Cakir, A.D.; Emeksiz, H.C.; Turan, I.; Delpouve, G.; Kardelen, A.D.; Ozcabi, B.; Isik, E.; Mengen, E.; et al. Loss-of-Function Variants in SEMA3F and PLXNA3 Encoding Semaphorin-3F and Its Receptor Plexin-A3 Respectively Cause Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Nguyen, D.T.; Choi, M.; Cha, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Dadi, H.; Seo, H.G.; Seo, K.; Chun, T.; Park, C. Analysis of Cattle Olfactory Subgenome: The First Detail Study on the Characteristics of the Complete Olfactory Receptor Repertoire of a Ruminant. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, E.E.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G.E. The Essence of Appetite: Does Olfactory Receptor Variation Play a Role? J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandl, K.; Tomisato, W.; Li, X.; Neppl, C.; Pirie, E.; Falk, W.; Xia, Y.; Moresco, E.M.Y.; Baccala, R.; Theofilopoulos, A.N.; et al. Yip1 Domain Family, Member 6 (Yipf6) Mutation Induces Spontaneous Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12650–12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mazagova, M.; Pan, C.; Yang, S.; Brandl, K.; Liu, J.; Reilly, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Loomba, R.; et al. YIPF6 Controls Sorting of FGF21 into COPII Vesicles and Promotes Obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 15184–15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houy, S.; Estay-Ahumada, C.; Croisé, P.; Calco, V.; Haeberlé, A.M.; Bailly, Y.; Billuart, P.; Vitale, N.; Bader, M.F.; Ory, S.; et al. Oligophrenin-1 Connects Exocytotic Fusion to Compensatory Endocytosis in Neuroendocrine Cells. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 11045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.Y.; Savegnago, R.P.; Lim, D.; Lee, S.H.; Gondro, C. Signatures of Selection in Angus and Hanwoo Beef Cattle Using Imputed Whole Genome Sequence Data. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1368710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, H.; Rotival, M.; Pothlichet, J.; Loh, Y.H.E.; Dannemann, M.; Zidane, N.; Laval, G.; Patin, E.; Harmant, C.; Lopez, M.; et al. Genetic Adaptation and Neandertal Admixture Shaped the Immune System of Human Populations. Cell 2016, 167, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, D.A.; El Hussein, A.M.; Kyule, M.N.; Zessin, K.H.; Ahmed, J.S.; Seitzer, U. Determination of Potential Risk Factors Associated with Theileria Annulata and Theileria Parva Infections of Cattle in the Sudan. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 101, 1285–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaker, I.A.; Salih, D.A.; El Haj, L.M.; Ahmed, R.E.; Osman, M.M.; Ali, A.M. Prevalence of Theileria Annulata in Dairy Cattle in Nyala, South Darfur State, Sudan. Vet. World 2017, 10, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayati, M.A.; Hassan, S.M.; Ahmed, S.K.; Salih, D.A. Prevalence of Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) and Theileria Annulata Infection of Cattle in Gezira State, Sudan. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2020, 10, e00148, Erratum in Parasitol Res. 2016, 115, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed-Ahmed, G.M.; Hassan, S.M.; El Hussein, A.M.; Salih, D.A. Molecular, Serological and Parasitological Survey of Theileria Annulata in North Kordofan State, Sudan. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2018, 13, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attili, A.; Tambella, A.M.; Preziuso, S.; Ngwa, V.N.; Moriconi, M.; Falcone, R.; Marconi, M.; Cuteri, V. Burkholderia Cepacia Complex in Clinically-Infected Animals: Retrospective Analysis, Antibiotic Resistance, and Potential Hazard for Public Health. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 23, 1450. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256080384_Burkholderia_cepacia_complex_in_clinically-infected_animals_retrospective_analysis_antibiotic_resistance_and_potential_hazard_for_public_health (accessed on 21 January 2025).

| Region of Signature Selection | Length (kb) | No. of Variants | Flanking Genes ±250 kb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butana (versus Kenana) | |||

| 5: 49,459,819–49,459,819 | 0.00 | 1 | TBK1, XPOT, C5H12orf56, KICS2, SRGAP1 |

| 27: 25,367,215–25,367,462 | 0.25 | 10 | PPP1R3B, TNKS |

| Kenana (versus Butana) | |||

| 5: 103,099,474–103,100,164 | 0.69 | 13 | ENSBTAG00000039256, ENSBTAG00000050301, CD163L1, PEX5, CLSTN3, RBP5, C1RL, ENSBTAG00000050749, ENSBTAG00000037743 |

| 10: 23,772,862–23,772,862 | 0.00 | 1 | ENSBTAG00000051554, ENSBTAG00000048374, ENSBTAG00000052580, ENSBTAG00000048874, TRAV24, ENSBTAG00000052314 |

| 15: 46,039,792–46,085,328 | 45.54 | 4 | OR2D2, OR10A4, OR10A5, OR10A5L, OR10A5G, OR6A2, OR6B18, ENSBTAG00000027525, OR6B17, ENSBTAG00000037603, OR2D4, OR2D3G, OR2AG1E, OR2AG1G, OR2AG1, OR2AG2, OR2D37, ENSBTAG00000051394, ENSBTAG00000037937, ENSBTAG00000049294 |

| Butana (versus Holstein) | |||

| X: 37,758,460–37,758,587 | 0.13 | 12 | FAM50A, PLXNA3, LAGE3, ENSBTAG00000014331, SLC10A3, FAM3A, G6PD, ENSBTAG00000053534, IKBKG, ENSBTAG00000001900, ENSBTAG00000048914, ENSBTAG00000055292, ENSBTAG00000053848, ENSBTAG00000052652 |

| Holstein (versus Butana) | |||

| 5: 59,654,384–59,657,407 | 3.02 | 15 | OR9K2I, OR9K2H, OR9K2K, OR9K2C, ENSBTAG00000045722, ENSBTAG00000054855, OR9K2, OR9K15, OR9K1, OR9K2F, OR9K1B, NEUROD4 |

| 28: 319,705–319,705 | 0.00 | 1 | ENSBTAG00000038418, OR5D18K, OR5L20, OR5AS1 |

| X: 82,098,289–82,098,601 | 0.31 | 5 | YIPF6, OPHN1, ENSBTAG00000052786 |

| Taxon Name | Taxon ID | Min | Max | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosea vestrisii | 151416 | 17 | 196,724 | 12 | 131,272 | 79,955 |

| Bosea sp. Tri-49 | 1867715 | 14 | 236,073 | 15 | 125,753 | 106,967 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | 105219 | 5419 | 278,625 | 22 | 78,512 | 103,706 |

| Theileria annulata | 5874 | 7282 | 259,012 | 22 | 71,638 | 72,619 |

| Botrytis cinerea | 40559 | 10,118 | 173,623 | 8 | 54,423 | 67,049 |

| Bosea beijingensis | 3068632 | 35 | 23,161 | 10 | 18,501 | 6651 |

| Bosea sp. (in: a-proteobacteria) | 1871050 | 142 | 20,174 | 10 | 16,335 | 5824 |

| Bosea sp. F3-2 | 2599640 | 33 | 22,410 | 11 | 16,332 | 8192 |

| Variovorax paradoxus | 34073 | 70 | 22,751 | 22 | 14,694 | 6100 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | 95486 | 54 | 169,760 | 22 | 14,410 | 39,918 |

| Novosphingobium sp. EMRT-2 | 2571749 | 6096 | 19,721 | 21 | 14,149 | 3119 |

| Bosea sp. NBC_00550 | 2969621 | 20 | 18,145 | 11 | 13,299 | 6647 |

| Bosea sp. UC22_33 | 3350165 | 54 | 16,451 | 10 | 13,079 | 4723 |

| Bosea sp. RAC05 | 1842539 | 30 | 15,242 | 10 | 12,217 | 4404 |

| Bosea sp. PAMC 26642 | 1792307 | 26 | 14,504 | 10 | 11,357 | 4123 |

| Bosea sp. ANAM02 | 2020412 | 26 | 15,277 | 11 | 11,247 | 5627 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 40324 | 121 | 36,873 | 22 | 10,556 | 8575 |

| Bosea sp. 685 | 3080057 | 41 | 12,778 | 10 | 10,175 | 3667 |

| Bosea vaviloviae | 1526658 | 39 | 12,369 | 10 | 9623 | 3473 |

| Bosea sp. AS-1 | 2015316 | 20 | 13,504 | 12 | 9115 | 5528 |

| Microviridae sp. | 2202644 | 12 | 24,457 | 3 | 8162 | 14,112 |

| Variovorax sp. UC74_104 | 3374555 | 49 | 13,082 | 22 | 7929 | 3911 |

| Variovorax sp. V15 | 3065952 | 46 | 9775 | 22 | 5910 | 2887 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neumann, G.B.; Korkuć, P.; Rahmatalla, S.A.; Reißmann, M.; Omer, E.A.M.; Elzaki, S.; Brockmann, G.A. Surviving the Heat: Genetic Diversity and Adaptation in Sudanese Butana Cattle. Genes 2025, 16, 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121429

Neumann GB, Korkuć P, Rahmatalla SA, Reißmann M, Omer EAM, Elzaki S, Brockmann GA. Surviving the Heat: Genetic Diversity and Adaptation in Sudanese Butana Cattle. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121429

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeumann, Guilherme B., Paula Korkuć, Siham A. Rahmatalla, Monika Reißmann, Elhady A. M. Omer, Salma Elzaki, and Gudrun A. Brockmann. 2025. "Surviving the Heat: Genetic Diversity and Adaptation in Sudanese Butana Cattle" Genes 16, no. 12: 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121429

APA StyleNeumann, G. B., Korkuć, P., Rahmatalla, S. A., Reißmann, M., Omer, E. A. M., Elzaki, S., & Brockmann, G. A. (2025). Surviving the Heat: Genetic Diversity and Adaptation in Sudanese Butana Cattle. Genes, 16(12), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121429