Abstract

Autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disability characterised by the impairment of social interaction and communication ability. The alarming increase in its prevalence in children urged researchers to obtain a better understanding of the causes of this disease. Genetic factors are considered to be crucial, as ASD has a tendency to run in families. In recent years, with technological advances, the importance of structural variations (SVs) in ASD began to emerge. Most of these studies, however, focus on the Caucasian population. As a populated ethnicity, ASD shall be a significant health issue in China. This systematic review aims to summarise current case-control studies of SVs associated with ASD in the Chinese population. A list of genes identified in the nine included studies is provided. It also reveals that similar research focusing on other genetic backgrounds is demanded to manifest the disease etiology in different ethnic groups, and assist the development of accurate ethnic-oriented genetic diagnosis.

Keywords:

autism spectrum disorder; ASD; autism; structural variation; copy number variation; CNV; genetics; Chinese; China; Han 1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterised by diverse symptoms that affect communication, behaviour, and social interactions. For a period, the prevalence of the disorder in the US was believed to be around 1 in 110 children (data of 2006), but it was found that it raised substantially to 1 out of 36 in a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [1]. In China, according to an investigation in 2019, the prevalence of ASD children was 1%, which is comparable to the worldwide data, but the number was believed to be underestimated due to lack of awareness of the disorder and therefore under diagnosis [2].

To dissect the cause of ASD, studies focusing on genetic, environmental, and psychological aspects were conducted, and both genetic and environmental risk factors were identified [3,4,5]. Genetic factors are estimated to account for 40 to 80 percent of ASD risk. Most of the research on genetic factors focuses on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of candidate genes associated with ASD [6,7]. Recent advances in genomic technologies ushered in a new era of understanding the genetic basis of ASD, highlighting the significant role of genetic variations in its etiology [8]. Among the genetic anomalies, structural variations (SVs), such as deletions, duplications, inversions, and copy number variations (CNVs), were identified as pivotal contributors to the disorder. These variations can disrupt gene functions or modify gene dosage, ultimately affecting synaptic plasticity and brain development. In the last two decades, our technology in genomic study gently transformed from sequence-based to assembly-based techniques. New methods, such as those of Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), are typical examples of assembly based approaches [9]. Integration of these technologies with some evolving techniques, such as optical mapping, were shown to be powerful in the construction of genomes [10,11]. With these advancements, long sequence reads were made possible, which is critical to the discovery of SVs that commonly span from kilo to mega bases.

The research of genetic variations in ASD was extensive [12,13]. However, much of this was conducted in Caucasian populations, leaving a gap in the understanding of how ASD manifests in non-Caucasian populations, including the Chinese population, which contributes to 17% of the world’s population. From a research perspective, these differences highlight the need for a globally inclusive genetic database that encompasses diverse populations to ensure that genetic studies of ASD are universally applicable and not biased towards specific genetic ancestries. Clinically, understanding these differences is crucial for the development of diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies that are effective across different genetic backgrounds [14]. For instance, genetic testing protocols optimised for Western populations may need adjustment to be as effective in Chinese populations due to these differences in SV prevalence and impact [15]. This line of inquiry is crucial given the genetic and environmental differences that may influence the prevalence and manifestations of ASD in different ethnic groups.

The current review aims to summarise the types of SVs reported in ASD among the Chinese population. It also discusses the genes potentially implicated in ASD. By examining the intersection of genetics and ethnicity, this review seeks to enhance the understanding of ASD’s complex etiology and pave the way for more effective interventions tailored to different populations.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and registered in Inplasy (INPLASY202480073) [16].

2.1. Search Strategy

Literature searches were completed in five Western databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid Medline, Ovid Nursing, and CINAHL, and four Chinese databases, including CNKI, Wanfang, Sinomed, and VIP. Searches in electronic databases identified studies published from inception to March 2024. Keywords used for searching included “Autism OR Autistic” AND “Structural varia* OR Transposition* OR Transposon* OR Retrotransposition* OR Retrotransposon* OR Insertion* OR Deletion* OR Indels OR Translocation* OR Inversion* OR Tandem repeat* OR Duplication* OR Copy number varia* OR Copy number polymorphism* OR Chromosomal rearrangement* OR Recombination* OR Microdeletion* OR Genomic varia*” AND “China OR Chinese OR Han”. Studies were extracted from systematic literature search following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included (i) human case-control cohort studies; (ii) ASD cohort recognised using any standard diagnostic criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or other clinical diagnosis). Exclusion criteria included: (i) studies not having a control group; (ii) non-English/Chinese publication; (iii) in vitro and/or animal studies; and (iv) abstracts, reviews, and study protocol.

2.2. Data Extraction

The Covidence software was used to remove duplicated articles and then screen the title and abstracts of the retrieved articles. Articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria were subsequently evaluated in full text and were assessed for their suitability for data extraction and analysis. The screening and data extraction of the articles were conducted by two authors independently. Any discrepancies regarding inclusion were resolved through discussion and consensus among the researchers involved.

2.3. Quality Assessment

Risk of bias assessment of the articles was conducted by two authors independently. Discrepancies in ratings were resolved by discussion and consensus. The assessment of study quality was carried out using 8 specific items derived from the Strengthening the Reporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA) checklist [17]. The assessment criteria include a thorough description of several key aspects: (1) the genotyping methodology of the studies, such as laboratory methods, the centre that performed the genotyping, the method of false positive detection, indication of whether experiments were performed in one batch; (2) detailed data analysis approaches, including the number of samples successfully genotyped, the control of population stratification, and the methods to determine SVs; and (3) the results of the studies, indicating whether the genetic variations are reported for the first time. Each checklist item achieved by the studies earns one point. Items not met received a zero [18].

3. Results

3.1. Search Result

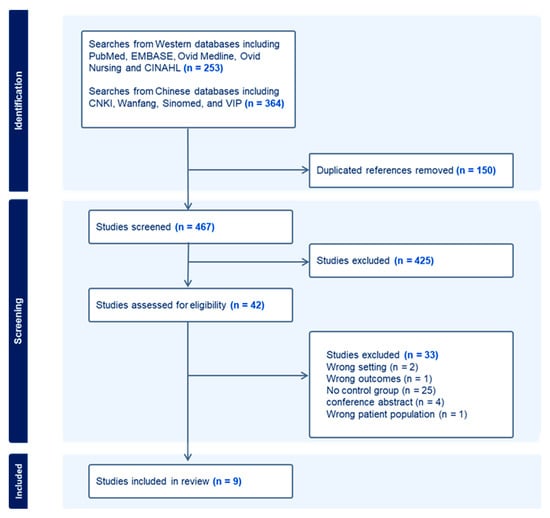

As shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), the systematic search strategy identified 253 publications from Western databases and 364 from Chinese databases, of which 150 were duplicates. The remaining 467 studies were screened by two reviewers for relevance by title and abstract, resulting in the removal of 425 studies. Full text screening of the remaining 42 studies excluded a further 33 studies, which did not meet inclusion criteria. Most excluded studies had no control group (n = 25). Other reasons for exclusion include wrong setting (n = 2), wrong outcomes (n = 1), wrong patient population (n = 1), and not a full research publication (n = 1). Finally, a total of nine studies, which fulfilled inclusion criteria, were included and evaluated in this systematic review [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Eight studies were published in English and one in Chinese language.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the study selection and exclusion process according to PRISMA guidelines.

3.2. Overview of Included Studies

Table 1 characterised the studies included in this review [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. The studies were published between 2011 and 2020. Except one study that was conducted in Taiwan, and one study that was conducted in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, all other studies were conducted in mainland China. The number of ASD subjects recruited ranged from 66 to 539. The diagnostic methods used to identify ASD individuals in the studies included the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Autism Behaviour Checklist (ABC), and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies.

3.3. Study Quality Assessment

The STREGA ratings of each included study are presented in Table 2. Overall, the quality of reporting genetic associations among the studies was low-moderate with a mean score at 3.7 and a score ranging between 2 and 6. All included studies described genotyping methods and platforms, and how the SVs were determined. None of the reports provide a hint on whether the genotyping was performed in one single batch or a few smaller batches. Only one study stated the centre at which genotyping was performed. Two studies described the methods used to control risk of false positives. About half of the studies reported the number of successful genotyping (56%) and stated whether the SVs were reported for the first time (45%). Among the nine included studies, three of them performed population stratification and two of which described how the classification was assessed.

Table 2.

Reporting the quality of the included studies by Strengthening the Reporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA).

3.4. Structural Variations Identification

Altogether, more than 70 SVs were reported in the included studies. Although the sizes of the SVs vary greatly, mainly due to the difference in technologies used, all CNVs involve deletions or duplications. Table 3 summarises the genes located at the SVs and their corresponding chromosomal banding. The SVs found could be de novo, maternal, or paternal in inheritance. The significance of some important genes implicated in autism, including CNTNAP2, GABRB3, JARID2, NLGN4X, NRXN1, PARK2, SHANK3, and UBE3A, were listed in Table 4 and reviewed in the discussion section of this review.

Table 3.

Summary of the structural variations reported in the included studies.

Table 4.

Summary of the genes reported in this review.

4. Discussion

In the present review, only nine studies were included. This reflects relevant research is lacking. This is not surprising because, firstly, the case-control study is more demanding, no matter the recruitment scale or experimental resources. However, case-control studies provide a more relevant comparison and effective analysis for exploring associations and risk factors. A familial study may be preferable when resources are limited. Secondly, the public awareness of ASD in China just started to emerge in the last two decades. With the development of standardised diagnostic instruments and the rise in public education of ASD in China, there shall be great potential to conduct similar research in the country considering the large population of Chinese people. Alongside the advancement of technologies in the discovery of SVs in genomics, a better understanding of the genetic factors for ASD in the Chinese population shall be attained. Nevertheless, studies in this review highlighted several key genes, namely CNTNAP2, GABRB3, JARID2, NLGN4X, NRXN1, PARK2, SHANK3, and UBE3A, that appear to play significant roles in the ASD. These genes are involved in various neural development processes, including synaptic formation, neuronal connectivity, and brain signalling pathways. Understanding these genes and their interactions offers potential for new therapeutic approaches and better diagnostic tools. Here we provide a quick recap of the important findings of these genes related to ASD.

4.1. CNTNAP2

Contactin-associated protein-like 2, encoded by the CNTNAP2 gene, is a synaptic cell adhesion molecule (CAMs). CNTNAP2 was pinpointed as a strong ASD risk gene by Baig et al. through in silico analysis of the relationship between genetic variants and protein structures [28]. The study illustrated that variants in CNTNAP2 can distort neuron–neuron interactions that are crucial for signal transmission across the synaptic gap. CNTNAP2 mutation altered the protein’s ability to bind with its synaptic partners, thereby impairing synaptic stability and plasticity. These distortions can affect critical areas of the brain, including language processing, cognitive function, and social behaviour, which are domains typically impacted in ASD [28]. Additionally, variants of CNTNAP2 trigger an abnormal activation of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), a marker of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. The activation of the ER stress response has significant implications for neuronal function and is linked to the developmental and functional abnormalities observed in ASD [29]. Findings of another study indicate that common variants in CNTNAP2 are associated with differences in the connectivity of specific brain regions involved in language processing and sensory integration. The study further provides evidence that the impact of CNTNAP2 on brain connectivity and multisensory integration might contribute to the communication difficulties observed in ASD [30].

4.2. GABRB3

γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit β-3 (GABRB3) is a subunit of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, which conducts inhibitory signals in the central nervous system. Studies demonstrated that variants in the GABRB3 gene are significantly associated with Asperger syndrome, a subtype of ASD. Moreover, these genetic variations are linked to a range of autism-related endophenotypes, such as sensory processing difficulties, issues with social cognition, and other cognitive challenges that are frequently observed in individuals with ASD [31]. The study also suggests that these associations may be due to the role of GABRB3 in modulating inhibitory neurotransmission, which affects neural connectivity and the functional organisation of the brain [31]. Findings from other studies indicate that variants in the GABRB3 gene are significantly associated with an increased risk of ASD by altering GABAergic signalling [32,33]. As GABA is a typical target in neurological diseases, diuretic bumetanide was investigated as a treatment of ASD [34].

4.3. JARID2

Jumanji, AT rich interactive domain 2 (JARID2) is located within chromosome 6p22.3. The gene product, Jumanji, is involved in the regulation of chromatin structure and gene expression through its interaction with the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2). Deletion of the region 6p22.3-p24.3, which affects not only JARID2 but also neighbouring genes, suggested a complex interaction between multiple genes, including ATXN1, that contribute to the risk of ASD [35]. In a study of 16 patients with deletion of, or SNPs within, the JARID2 gene alone, 16% were diagnosed with ASD, while all showed developmental delay [36]. The GWAS analysis conducted in another study pinpointed specific loci within the JARID2 gene that were significantly associated with ASD in the East Asian cohort [37]. This finding suggests that JARID2 may exhibit a unique presentation in certain populations that was not revealed in other studies using a Caucasian population dataset.

4.4. NLGN4X

Neuroligin 4 X-linked (NLGN4X) encodes a protein that is a family member of neuroligins (NLGNs), which binds to neurexins (NRXNs) for the correct formation and maintenance of synapses in the brain [38]. Disruptions of the NLGNs-NRXNs interactions, caused by genetic alterations in NLGN4X, were implicated in the development of ASD [39]. In contrast, another study found no significant association between variants in the NLGN4X gene and the prevalence of ASD in the examined Chinese cohort [40]. The study provided several reasons why these findings might differ from other studies, including population genetic differences, sample size, and the specific genetic variants analysed. The absence of an association in this study indicates the complexity of ASD’s genetic interplay and suggests that the contributions of specific genes to the disorder may vary across different ethnic and genetic backgrounds [40].

4.5. NRXN1

The SHANK3-NLGN4-NRXN1 axis is a well-documented cascade responsible for synapse physiology. NRXNs, at the presynaptic side, and NLGNs, at the postsynaptic side, interact with each other to form functional synapses [41]. Mutation of the neurexins 1 gene (NRXN1) was firstly targeted by Feng et al. (2006) for its interaction with neuroligins (NLGNs). They confirmed the contribution of NRXN1 to autism susceptibility [42]. In a large-scale comparative analysis involving over 1181 ASD families, hemizygous deletion of NRXN1 was found to be associated with ASD [43]. NRXN1 is located at chromosome 2p16.1. Kim et al. mapped breakpoints in this region in two ASD patients [44]. NRXN1 was again identified as an ASD candidate gene by Glessner et al. using genome-wide high-resolution CNV detection [45]. More single nucleotide and structural variants of NRXN1 were reported in ASD patients subsequently [46,47,48]. In a study of whole exon sequencing of 343 ASD families, NRXN1 was revealed as the only one candidate gene for autism [49]. Interestingly, according to Wang et al., among the polymorphisms selected in their study, two SNPs were found associated with NRXN2 and NRXN3, respectively, but not NRXN1 in Chinese ASD patients [50]. Deletion of NRXN1 was found to have strong association with autism, mental retardation, and language delay [51,52]. Taken together, NRXN1 is regarded as one of the strong candidate genes for autism.

4.6. PARK2

PARK2 (currently known as PRKN) encodes the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase Parkin, which is responsible for proteasomal degradation at the mitochondria. Mutation of the gene was heavily studied in Parkinson’s disease [53]. In the research of Dalla Vecchia et al., mutations or functional disruptions in PARK2 were found contributing to neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD, by affecting neuronal health and synaptic functioning [54]. Disruptions in PARK2 were suggested to impact mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, which were hypothesised to play roles in the development of ASD [54]. Additionally, animal models harbouring PARK2 mutations were shown to exhibit behavioural phenotypes resembling those presented in ASD, such as social deficits and repetitive behaviours [54]. In another study, PARK2 was identified as a locus where rare CNVs were more frequently observed in individuals with ASD compared to control groups [55]. The study demonstrated that alterations in PARK2 might lead to dysfunctional cellular mechanisms, particularly in neuronal cells, for which energy demand and protein regulation are critical for normal function [55]. Furthermore, this study underscores the importance of integrating different genetic approaches—such as examining both CNVs and single-nucleotide variations—to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic factors contributing to ASD.

4.7. SHANK3

SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (SHANK3), also known as ProSAP2, encodes a scaffolding protein at the excitatory synapses to enable proper positioning of neurotransmitter receptors [56]. SHANK3 is located on chromosome 22q13. Deletion of the gene would result in Phelan–McDermid syndrome [57]. Durand et al. and Moessner et al. both reported the association of mutations and rare nonsynonymous variants of SHANK3 with autism [58,59]. Later on, Schaaf et al. described SHANK3 as one of the genes involved in the oligogenic heterozygous events carried by ASD patients [60]. In a meta-analysis, Leblond et al. revealed that copy number variants and truncating mutations in SHANK genes were present in 0.7% of the ASD patients [61]. Recently, Loureiro et al. also reported a recurrent frameshift variant of SHANK3 in ASD patients [62]. SHANK3 was also reported in one of our included articles having a significantly higher ratio of heterozygous deletion in Chinese patients [22]. On top of genetic risk factors, the SHANK3 gene was extensively studied in neurobiology and in ASD disease pathology for its role in maintaining postsynaptic structure and hence synapse functioning [41,56].

4.8. UBE3A

Ubiquitin protein ligase E3A (UBE3A) is one of the most extensively studied autism-linked candidate genes. It is located at 15q11-q13, a region found to have a high frequency of chromosomal anomalies in ASD patients [63,64,65]. The gene product of UBE3A is responsible for protein degradation in a cell and deletion of the gene causes Angelman syndrome [66]. In an early study by Cook et al., no linkage disequilibrium could be found for the gene UBE3A with autism, including the marker D15S122 [67]. Later on, Nurmi et al. observed a significant linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the same marker in autism patients [68]. This LD result was not replicable when other markers in the region were used in a dense linkage mapping study [69]. Concurrently, Veenstra-Vanderweele et al. identified several polymorphisms of the gene in 10 ASD patients. No functional mutation was detected [70]. Later, Glessner et al. reported in their genome-wide study that a CNV affecting UBE3A was found exclusively in ASD patients but not in controls using MPLA and qPCR for detection [45]. In the development of the ASD diagnostic tool, Bremer et al. revealed clearly the duplication of 15q11-q13, which covers UBE3A, in two patients [71]. Iossifov et al. identified a missense mutation in ASD patients that led to the hypothesis that the phosphorylation of UBE3A is important for the pathophysiology of autism [72,73]. There are a couple of genome-wide screening targeting structural variations associated with autism. UBE3A was not pinpointed in those studies [43]. Although molecular and cellular analyses shaped a putative mechanism, a concrete linkage between UBE3A and autism is yet to be revealed [74]. The challenges possibly lie with the complexity of the genome in that region. The fact that UBE3A is imprinted adds another layer of variety in symptom presentation.

This is the first systematic review of case-control studies focusing on SVs in ASD of Chinese ancestry. Compared with a trio study, case-control research has the advantage of excluding a similar genetic background that runs in a family. Interestingly, it was noticed that genetic background still remained as a challenge in some of the included case-control studies as ethnicity constraints were applied. Among the nine included articles, two of them raised the concern about the disparity of variant frequencies between Chinese and Caucasian. One of the major findings of Gazzellone et al. is that, in their dataset, the microduplication of YWHAE has a high frequency (0.9%) in Chinese population regardless of ASD condition, while they could not detect any of this event in their Caucasian control [20]. Similarly, Siu et al. observed a heterozygous variant of c.3388C>T and c.2204-14_2204-2dup at a frequency of 0.045 in their Southern Han Chinese healthy controls, compared with the allele frequency of c.3388C>T being 0.0059 in the 1000 Genomes Project [24]. Apart from these two included studies, Mak et al. also identified a CNV polymorphism enriched in the Chinese population in their autism genetic study [75]. A range of research addressed the effect of ethnicity on CNV [76,77,78]. In the study by Lou et al., thousands of Asian-specific CNVs were reported, while several hundreds of CNVs specific to Han Chinese were identified [77]. Park et al. also identified 3547 putative Asian-specific CNVs among the 5177 CNVs they detected in their study [76]. These findings reflected that ancestry-matched control can be of critical importance in analysing genetic risk factors of SVs. By this token, using a population of a different ancestry background as control in genetic analysis would increase the probability of mistakes in scientific results and may even lead to misdiagnosis if applied in clinical settings [79].

To overcome this situation, genome sequences of diverse populations are essential for more reliable scientific results and for more precise clinical diagnoses. A diverse genetic database enables researchers to identify ethnic-specific genetic markers [80]. It provides hints to the understanding of ethnic-dependent disease pathology and health disparities [81]. In addition to enriching the wide breadth of biomedical knowledge, the information is needed for more accurate diagnosis for patients of different ancestral backgrounds [79,82]. It enables effective translation into clinical practice and promotes personalized therapies [83,84]. The establishment of a global inclusive genetic database requires the efforts of different stakeholders in the society, including academic, clinical, and governance sectors. The basis of success relies on strategies that reduce bias, from inclusive recruitment of participants to proper and fair data sharing, to safeguard privacy and eliminate discrimination, among the many key factors in necessity [85].

In conclusion, the present review sheds light on the demand of a globally inclusive genetic database that permits universal studies of genetic diseases that are not biased towards specific genetic ancestries. This will have significant implications for policy, clinical practice, and research, ultimately leading to more personalised, equitable, and effective healthcare solutions for people worldwide.

5. Limitations

This work reviews the extensive search of multiple databases and interpretation of results across different types of structural variations involving ASD. However, the limitation is that we were unable to complete a meta-analysis of SVs in ASD due to differences in study methodologies (e.g., selection of cases, diversion of participants) and analytical methods (e.g., sequencing thresholds, control for testing).

6. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on case-control studies of SVs in ASD within the Chinese population. This review retrieved nine included studies, of which the quality was assessed by the STREGA checklist as low to moderate. It is revealed in the present work that specific SVs, including deletions, duplications, and copy number variations, are prevalent in the Chinese ASD cohort, affecting genes crucial for neural development and synaptic function. Some important genes for ASD were implicated in the included studies, namely CNTNAP2, GABRB3, JARID2, NLGN4X, NRXN1, PARK2, SHANK3, and UBE3A. This review enriches our understanding of the genetic composition of ASD among the Chinese population. Importantly, the essential role of ethnicity in genetic research was highlighted, implying the pressing need of a diverse genetic database across different ethnicities for future research and the development of unbiased, better healthcare systems globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-Y.C., M.M.-Y.W. and K.-M.C.; methodology, J.Y.-W.C., C.W.-L.C. and B.M.-H.L.; writing, J.Y.-W.C. and C.W.-L.C.; review and editing, S.-Y.C., M.M.-Y.W., K.-M.C. and B.M.-H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maenner, M.J.; Warren, Z.; Williams, A.R.; Amoakohene, E.; Bakian, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Fitzgerald, R.T.; Furnier, S.M.; Hughes, M.M.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Allison, C.; Wei, L.; Matthews, F.E.; Auyeung, B.; Wu, Y.Y.; Griffiths, S.; Zhang, J.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Brayne, C. Autism prevalence in China is comparable to Western prevalence. Mol. Autism 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabit, H.; Tombuloglu, H.; Rehman, S.; Almandil, N.B.; Cevik, E.; Abdel-Ghany, S.; Rashwan, S.; Abasiyanik, M.F.; Yee Waye, M.M. Gut microbiota metabolites in autistic children: An epigenetic perspective. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waye, M.M.Y.; Cheng, H.Y. Genetics and epigenetics of autism: A Review. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.Y.; Menga, Y.J.; Li, T.; Huang, Y. Associations of endocrine stress-related gene polymorphisms with risk of autism spectrum disorders: Evidence from an integrated meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 1722–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; Yang, K.; Du, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Qiu, Z. Discovery and Validation of Novel Genes in a Large Chinese Autism Spectrum Disorder Cohort. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Guo, H.; Xiong, B.; Stessman, H.A.; Wu, H.; Coe, B.P.; Turner, T.N.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Hoekzema, K.; et al. De novo genic mutations among a Chinese autism spectrum disorder cohort. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.; Thiruvahindrapuram, B.; Chan, A.J.S.; Engchuan, W.; Higginbotham, E.J.; Howe, J.L.; Loureiro, L.O.; Reuter, M.S.; Roshandel, D.; Whitney, J.; et al. Genomic architecture of autism from comprehensive whole-genome sequence annotation. Cell 2022, 185, 4409–4427.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, M.D.; Harvey, W.T.; Porubsky, D.; Sulovari, A.; Li, R.; Rose, N.R.; Audano, P.A.; Munson, K.M.; Lewis, A.P.; Hoekzema, K.; et al. Familial long-read sequencing increases yield of de novo mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 109, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Lam, E.; Saghbini, M.; Bocklandt, S.; Hastie, A.; Cao, H.; Holmlin, E.; Borodkin, M. Structural Variation Detection and Analysis Using Bionano Optical Mapping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Faino, L.; Seidl, M.F.; Datema, E.; van den Berg, G.C.M.; Janssen, A.; Wittenberg, A.H.J.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Single-Molecule Real-Time Sequencing Combined with Optical Mapping Yields Completely Finished Fungal Genome. mBio 2015, 6, e00936-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, J.; Ripke, S.; Als, T.D.; Mattheisen, M.; Walters, R.K.; Won, H.; Pallesen, J.; Agerbo, E.; Andreassen, O.A.; Anney, R.; et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baio, J.; Wiggins, L.; Christensen, D.L.; Maenner, M.J.; Daniels, J.; Warren, Z.; Kurzius-Spencer, M.; Zahorodny, W.; Robinson Rosenberg, C.; White, T.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yin, Z.; Hou, M.; Guo, P.; Wang, H.; Liu, N.; Cai, C.; Wang, M. Comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between common genetic variants and autism spectrum disorder. Gene 2023, 887, 147723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parellada, M.; Andreu-Bernabeu, A.; Burdeus, M.; San Jose Caceres, A.; Urbiola, E.; Carpenter, L.L.; Kraguljac, N.V.; McDonald, W.M.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Rodriguez, C.I.; et al. In Search of Biomarkers to Guide Interventions in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Psychiatry 2023, 180, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Moher, D.; Gagnon, F.; Von Elm, E.; Khoury, M.J.; Cohen, B.; Davey-Smith, G.; Grimshaw, J.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)—An extension of the STROBE statement. Genet. Epidemiol. 2009, 33, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chair, S.Y.; Chan, J.Y.W.; Law, B.M.H.; Waye, M.M.Y.; Chien, W.T. Genetic susceptibility in pneumoconiosis in China: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2023, 96, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Du, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Yu, Y. Rare Copy Number Variations in a Chinese Cohort of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzellone, M.J.; Zhou, X.; Lionel, A.C.; Uddin, M.; Thiruvahindrapuram, B.; Liang, S.; Sun, C.; Wang, J.; Zou, M.; Tammimies, K.; et al. Copy number variation in Han Chinese individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2014, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Peng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xun, G.; Ou, J.; Sun, L.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; et al. Genome-wide copy number variation analysis in a Chinese autism spectrum disorder cohort. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; He, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, X.; Li, Q.; Sun, X. Correlation of Copy Number Variation in SHANK3, UBE3A and Other Autism Hot Gene Among Autism Children Based on Multiplex Ligation Probe Amplification and Whole-Genome Array Method. J. Mod. Lab. Med. 2011, 26, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xun, G.; Peng, Y.; Lu, L.; Xu, X.; Xiong, Z.; Xia, L.; Liu, D.; Li, W.; et al. Mutation analysis of the NRXN1 gene in a Chinese autism cohort. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, W.K.; Lam, C.W.; Gao, W.W.; Vincent Tang, H.M.; Jin, D.Y.; Mak, C.M. Unmasking a novel disease gene NEO1 associated with autism spectrum disorders by a hemizygous deletion on chromosome 15 and a functional polymorphism. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 300, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.L.; Chen, H.I.; Li, L.H.; Chien, Y.L.; Liao, H.M.; Chou, M.C.; Chou, W.J.; Tsai, W.C.; Chiu, Y.N.; Wu, Y.Y.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of copy number variations identifies PARK2 as a candidate gene for autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2016, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Yu, S. Mutation screening of the UBE3A gene in Chinese Han population with autism. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Lin, X.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, C.; Wu, Q.; Ye, A.Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Targeted resequencing of 358 candidate genes for autism spectrum disorder in a Chinese cohort reveals diagnostic potential and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, D.N.; Yanagawa, T.; Tabuchi, K. Distortion of the normal function of synaptic cell adhesion molecules by genetic variants as a risk for autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. Bull. 2017, 129, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falivelli, G.; De Jaco, A.; Favaloro, F.L.; Kim, H.; Wilson, J.; Dubi, N.; Ellisman, M.H.; Abrahams, B.S.; Taylor, P.; Comoletti, D. Inherited genetic variants in autism-related CNTNAP2 show perturbed trafficking and ATF6 activation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 4761–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.A.; Del Bene, V.A.; Molholm, S.; Woo, Y.J.; Andrade, G.N.; Abrahams, B.S.; Foxe, J.J. Common variation in the autism risk gene CNTNAP2, brain structural connectivity and multisensory speech integration. Brain Lang. 2017, 174, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, V.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Chakrabarti, B. Genetic variation in GABRB3 is associated with Asperger syndrome and multiple endophenotypes relevant to autism. Mol. Autism 2013, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskunpinar, E.M.; Tur, S.; Cevher Binici, N.; Yazan Songur, C. Association of GABRG3, GABRB3, HTR2A gene variants with autism spectrum disorder. Gene 2023, 870, 147399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.Q.; Barnes, G. A common susceptibility factor of both autism and epilepsy: Functional deficiency of GABA A receptors. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellot, G.; Cherubini, E. GABAergic Signaling as Therapeutic Target for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Pediatr. 2014, 2, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino-Soper, P.B.; Skinner, C.; Schroer, R.; Eng, P.; Shenai, J.; Nowaczyk, M.M.; Terespolsky, D.; Cushing, D.; Patel, G.S.; Immken, L.; et al. Deletions in chromosome 6p22.3-p24.3, including ATXN1, are associated with developmental delay and autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Cytogenet. 2012, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberne, E.A.; Goh, S.; England, J.; Van Ginkel, M.; Rafael-Croes, L.; Maas, S.; Polstra, A.; Zarate, Y.A.; Bosanko, K.A.; Pechter, K.B.; et al. JARID2 haploinsufficiency is associated with a clinically distinct neurodevelopmental syndrome. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shimada, T.; Otowa, T.; Wu, Y.Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Tochigi, M.; Iwata, Y.; Umekage, T.; Toyota, T.; Maekawa, M.; et al. Genome-wide Association Study of Autism Spectrum Disorder in the East Asian Populations. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Südhof, T.C. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature 2008, 455, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, P.; Comoletti, D.; Ferracci, G.; Conrod, S.; Garcia, S.U.; Taylor, P.; Bourne, Y.; Marchot, P. Structural insights into the exquisite selectivity of neurexin/neuroligin synaptic interactions. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 2461–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Du, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Gong, X. Lack of association between NLGN3, NLGN4, SHANK2 and SHANK3 gene variants and autism spectrum disorder in a Chinese population. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.-C.; Lin, L.-S.; Long, S.; Ke, X.-Y.; Fukunaga, K.; Lu, Y.-M.; Han, F. Signalling pathways in autism spectrum disorder: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Schroer, R.; Yan, J.; Song, W.; Yang, C.; Bockholt, A.; Cook, E.H., Jr.; Skinner, C.; Schwartz, C.E.; Sommer, S.S. High frequency of neurexin 1β signal peptide structural variants in patients with autism. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 409, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Autism Genome Project, C.; Szatmari, P.; Paterson, A.D.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Roberts, W.; Brian, J.; Liu, X.Q.; Vincent, J.B.; Skaug, J.L.; Thompson, A.P.; et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-G.; Kishikawa, S.; Higgins, A.W.; Seong, I.-S.; Donovan, D.J.; Shen, Y.; Lally, E.; Weiss, L.A.; Najm, J.; Kutsche, K.; et al. Disruption of Neurexin 1 Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glessner, J.T.; Wang, K.; Cai, G.; Korvatska, O.; Kim, C.E.; Wood, S.; Zhang, H.; Estes, A.; Brune, C.W.; Bradfield, J.P. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature 2009, 459, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Noltner, K.; Feng, J.; Li, W.; Schroer, R.; Skinner, C.; Zeng, W.; Schwartz, C.E.; Sommer, S.S. Neurexin 1 structural variants associated with autism. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 438, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.M.; An, J.Y.; Edson, J.; Watts, M.; Murigneux, V.; Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Jackson, C.J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Cristino, A.S.; Claudianos, C. An integrative analysis of non-coding regulatory DNA variations associated with autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniowiecka-Kowalnik, B.; Nesteruk, M.; Peters, S.U.; Xia, Z.; Cooper, M.L.; Savage, S.; Amato, R.S.; Bader, P.; Browning, M.F.; Haun, C.L.; et al. Intragenic rearrangements in NRXN1 in three families with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and speech delay. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153B, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossifov, I.; Ronemus, M.; Levy, D.; Wang, Z.; Hakker, I.; Rosenbaum, J.; Yamrom, B.; Lee, Y.-H.; Narzisi, G.; Leotta, A.; et al. De Novo Gene Disruptions in Children on the Autistic Spectrum. Neuron 2012, 74, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, J.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Gu, H.; Luo, X.; Hou, F.; Zhang, J.; Song, R. Neurexin gene family variants as risk factors for autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shehhi, M.; Forman, E.B.; Fitzgerald, J.E.; McInerney, V.; Krawczyk, J.; Shen, S.; Betts, D.R.; Ardle, L.M.; Gorman, K.M.; King, M.D.; et al. NRXN1 deletion syndrome; phenotypic and penetrance data from 34 families. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 62, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, M.S.L.; Shen, Y.; Tan, W.H.; Jeste, S.S.; Morrow, E.M.; Chen, X.; Mukaddes, N.M.; Yoo, S.Y.; Hanson, E.; Hundley, R.; et al. Deletions of NRXN1 (neurexin-1) predispose to a wide spectrum of developmental disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153B, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilarski, L.L.; Pearson, J.P.; Newsway, V.; Majounie, E.; Knipe, M.D.W.; Misbahuddin, A.; Chinnery, P.F.; Burn, D.J.; Clarke, C.E.; Marion, M.H.; et al. Systematic Review and UK-Based Study of PARK2 (parkin), PINK1, PARK7 (DJ-1) and LRRK2 in early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Vecchia, E.; Mortimer, N.; Palladino, V.S.; Kittel-Schneider, S.; Lesch, K.P.; Reif, A.; Schenck, A.; Norton, W.H.J. Cross-species models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: Lessons from CNTNAP2, ADGRL3, and PARK2. Psychiatr. Genet. 2019, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchelli, E.; Cameli, C.; Viggiano, M.; Igliozzi, R.; Mancini, A.; Tancredi, R.; Battaglia, A.; Maestrini, E. An integrated analysis of rare CNV and exome variation in Autism Spectrum Disorder using the Infinium PsychArray. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, P.; Feng, G. SHANK proteins: Roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitz, A.R.; Philyaw, T.J.; Boccuto, L.; Shcheglovitov, A.; Sarasua, S.M.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Thurm, A. Identification of 22q13 genes most likely to contribute to Phelan McDermid syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, C.M.; Betancur, C.; Boeckers, T.M.; Bockmann, J.; Chaste, P.; Fauchereau, F.; Nygren, G.; Rastam, M.; Gillberg, I.C.; Anckarsäter, H.; et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moessner, R.; Marshall, C.R.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Skaug, J.; Pinto, D.; Vincent, J.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Fernandez, B.; Roberts, W.; Szatmari, P. Contribution of SHANK3 mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, C.P.; Sabo, A.; Sakai, Y.; Crosby, J.; Muzny, D.; Hawes, A.; Lewis, L.; Akbar, H.; Varghese, R.; Boerwinkle, E.; et al. Oligogenic heterozygosity in individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 3366–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblond, C.S.; Nava, C.; Polge, A.; Gauthier, J.; Huguet, G.; Lumbroso, S.; Giuliano, F.; Stordeur, C.; Depienne, C.; Mouzat, K.; et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Gradient of Severity in Cognitive Impairments. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, L.O.; Howe, J.L.; Reuter, M.S.; Iaboni, A.; Calli, K.; Roshandel, D.; Pritisanac, I.; Moses, A.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Trost, B.; et al. A recurrent SHANK3 frameshift variant in Autism Spectrum Disorder. NPJ Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra-Vanderweele, J.; Cook, E.H. Molecular genetics of autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2004, 9, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depienne, C.; Moreno-De-Luca, D.; Heron, D.; Bouteiller, D.; Gennetier, A.; Delorme, R.; Chaste, P.; Siffroi, J.-P.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Benyahia, B. Screening for genomic rearrangements and methylation abnormalities of the 15q11-q13 region in autism spectrum disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen-Brady, K.; Robison, R.; Cannon, D.; Varvil, T.; Villalobos, M.; Pingree, C.; Leppert, M.; Miller, J.; McMahon, W.; Coon, H. Genome-wide linkage in Utah autism pedigrees. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishino, T.; Lalande, M.; Wagstaff, J. UBE3A/E6-AP mutations cause Angelman syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.H., Jr.; Courchesne, R.Y.; Cox, N.J.; Lord, C.; Gonen, D.; Guter, S.J.; Lincoln, A.; Nix, K.; Haas, R.; Leventhal, B.L.; et al. Linkage-disequilibrium mapping of autistic disorder, with 15q11-13 markers. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 62, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, E.L.; Bradford, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hall, J.; Arnone, B.; Gardiner, M.B.; Hutcheson, H.B.; Gilbert, J.R.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Copeland-Yates, S.A.; et al. Linkage disequilibrium at the Angelman syndrome gene UBE3A in autism families. Genomics 2001, 77, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, E.L.; Amin, T.; Olson, L.M.; Jacobs, M.M.; McCauley, J.L.; Lam, A.Y.; Organ, E.L.; Folstein, S.E.; Haines, J.L.; Sutcliffe, J.S. Dense linkage disequilibrium mapping in the 15q11–q13 maternal expression domain yields evidence for association in autism. Mol. Psychiatry 2003, 8, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Veenstra-Vanderweele, J.; Gonen, D.; Leventhal, B.L.; Jr, E.C. Mutation screening of the UBE3A /E6-AP gene in autistic disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 1999, 4, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bremer, A.; Giacobini, M.; Nordenskjöld, M.; Brøndum-Nielsen, K.; Mansouri, M.; Dahl, N.; Anderlid, B.; Schoumans, J. Screening for copy number alterations in loci associated with autism spectrum disorders by two-color multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153B, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, J.Y.; Berrios, J.; Newbern, J.M.; Snider, W.D.; Philpot, B.D.; Hahn, K.M.; Zylka, M.J. An autism-linked mutation disables phosphorylation control of UBE3A. Cell 2015, 162, 795–807. [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov, I.; O’roak, B.J.; Sanders, S.J.; Ronemus, M.; Krumm, N.; Levy, D.; Stessman, H.A.; Witherspoon, K.T.; Vives, L.; Patterson, K.E. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature 2014, 515, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, P.L.; Hanayama, R.; Bloodgood, B.L.; Mardinly, A.R.; Lipton, D.M.; Flavell, S.W.; Kim, T.-K.; Griffith, E.C.; Waldon, Z.; Maehr, R.; et al. The Angelman Syndrome Protein Ube3A Regulates Synapse Development by Ubiquitinating Arc. Cell 2010, 140, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.S.L.; Chiu, A.T.G.; Leung, G.K.C.; Mak, C.C.Y.; Chu, Y.W.Y.; Mok, G.T.K.; Tang, W.F.; Chan, K.Y.K.; Tang, M.H.Y.; Lau Yim, E.T.-K.; et al. Use of clinical chromosomal microarray in Chinese patients with autism spectrum disorder—Implications of a copy number variation involving DPP10. Mol. Autism 2017, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.-I.; Ju, Y.S.; Gokcumen, O.; Mills, R.E.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Suh, D.; Hong, D.; Kang, H.P.; et al. Discovery of common Asian copy number variants using integrated high-resolution array CGH and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, H.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Kang, L.; Zhang, X.; Jin, W.; Wu, B.; Jin, L.; Xu, S. A Map of Copy Number Variations in Chinese Populations. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Lou, H.; Fu, R.; Lu, D.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Fang, B.; Pu, F.; et al. Assessing genome-wide copy number variation in the Han Chinese population. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrai, A.K.; Funke, B.H.; Rehm, H.L.; Olesen, M.S.; Maron, B.A.; Szolovits, P.; Margulies, D.M.; Loscalzo, J.; Kohane, I.S. Genetic Misdiagnoses and the Potential for Health Disparities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, C.E.; Batorsky, A.; Lee, M.K.; Szeto, M.D.; Xu, X.; McCartney, D.L.; Jiang, R.; Patki, A.; Kramer, H.J.; Eales, J.M.; et al. Epigenome-wide association study of kidney function identifies trans-ethnic and ethnic-specific loci. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.C.; Baena, A.; Thim, S.; Goldfeld, A.E. Ethnic-Specific Genetic Associations with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 186, 1463–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsberts, C.M.; Groenewegen, K.A.; Hoefer, I.E.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Anderson, T.J.; Britton, A.R.; Dekker, J.M.; Engström, G.; Evans, G.W.; et al. Race/Ethnic Differences in the Associations of the Framingham Risk Factors with Carotid IMT and Cardiovascular Events. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, V.E.; Meyers, D.A. Pharmacogenetics: Implications of race and ethnicity on defining genetic profiles for personalized medicine. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettig, L.; Sahnane, N.; Pepe, F.; Cerutti, R.; Albeni, C.; Franzi, F.; Veronesi, G.; Ogliari, F.; Pastore, A.; Tuzi, A.; et al. EGFR T790M detection rate in lung adenocarcinomas at baseline using droplet digital PCR and validation by ultra-deep next generation sequencing. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebbeck, T.R.; Bridges, J.F.P.; Mack, J.W.; Gray, S.W.; Trent, J.M.; George, S.; Crossnohere, N.L.; Paskett, E.D.; Painter, C.A.; Wagle, N.; et al. A Framework for Promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Genetics and Genomics Research. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e220603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).