Abstract

The mesocorticolimbic (MCL) system is crucial in developing risky health behaviors which lead to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Although there is some knowledge of the MCL system genes linked to CVDs and T2D, a comprehensive list is lacking, underscoring the significance of this review. This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The PubMed and Web of Science databases were searched intensively for articles related to the MCL system, single nucleotide variants (SNVs, formerly single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs), CVDs, T2D, and associated risk factors. Included studies had to involve a genotype with at least one MCL system gene (with an identified SNV) for all participants and the analysis of its link to CVDs, T2D, or associated risk factors. The quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the Q-Genie tool. The VEP and DAVID tools were used to annotate and interpret genetic variants and identify enriched pathways and gene ontology terms associated with the gene list. The review identified 77 articles that met the inclusion criteria. These articles provided information on 174 SNVs related to the MCL system that were linked to CVDs, T2D, or associated risk factors. The COMT gene was found to be significantly related to hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, obesity, and drug abuse, with rs4680 being the most commonly reported variant. This systematic review found a strong association between the MCL system and the risk of developing CVDs and T2D, suggesting that identifying genetic variations related to this system could help with disease prevention and treatment strategies.

1. Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) pose a significant global health challenge and are among the top causes of adult mortality worldwide [1]. In 2022, NCDs were estimated to account for 41 million (71%) of the 57 million global deaths, of which cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) caused 17.9 million (31%) of the global deaths and 44% of all deaths as a result of NCDs [1], whereas diabetes mellitus (DM) was attributed to 1.5 million (3%) of all global deaths and 4% of all NCD deaths [1]. Most NCDs share common risk factors, which are often categorized as behavioral or biological [2].

The mesocorticolimbic (MCL) system, originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) region of the brain [3], might play a crucial role in the development of key risky health behaviors leading to chronic NCDs of major public health importance. Studies have revealed that there is a strong association between the MCL system and the risk of developing CVDs [4,5]. A substantial body of research has demonstrated that certain single nucleotide variants (SNVs) of specific MCL genes are significant in the increased risk of CVDs. For instance, rs7396366, rs4680, and rs4714210 were found to be related to coronary artery disease [6]; rs4680 was associated with hypertension; rs4633 and rs4680 were linked to atherosclerosis [7]; and rs2097603, rs4633, rs4680, and rs174699 were associated with venous thrombosis [8]. Additionally, rs324420 was found to be related to an increased heart rate [9]. The mesolimbic system plays important roles in the regulation of behavior, vulnerability to stress, and drug abuse [10,11]. Stress is a potential activator of mesolimbic and mesocortical projections [12,13]. It is also associated with noticeable cardiovascular responses, like differential vasoconstrictor response, change in blood pressure, and heart rate [14,15]. The MCL system also regulates optimal cardiovascular responses such as the assimilation of sensory and behavioral information with cardiovascular homeostasis [4,14,16]. To sum up, it works as a connector between behaviors like locomotory and cognitive, and cardiovascular homeostasis, which result in CVDs [4,14].

Likewise, studies have revealed that the MCL system has some impacts on the etiology and pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and metabolic syndrome (MS) [17,18]. An animal experiment showed that increased dopamine tone in mesolimbic brain areas leads to an increased value of various rewarding stimuli, including food intake [19,20]. This fact may have determined an increased motivation for food consumption in the test animals, which at later stages, could result in obesity and deficits in glucose control [21].

Furthermore, environmental and genetic risk factors influence the incidence and severity of CVDs and T2D. Other behavioral risk factors that contribute to the development of CVDs and T2D are smoking, excessive alcohol intake, poor diet, drug addiction, and physical inactivity [22,23]. These lifestyle factors are closely linked to the MCL system, which involves a complex interplay between genetic and environmental influences. Research indicates that variations in MCL genes can increase susceptibility to CVDs and T2D among individuals with these risk factors [22,23]. Genome-wide association studies have revealed that heterogeneity can result in different susceptible genes being associated with CVDs and T2D [24,25].

Identifying genetic variants linked to the development of, or considered risk factors for, CVDs and T2D is critical for disease prevention and therapy. There is no comprehensive information from genetic association research on MCL system genes that have been identified as risk factors for CVDs and T2D. Therefore, this systematic review was undertaken to give a complete list of SNVs of the MCL system that are related to CVDs and T2D, as well as their possible risk factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

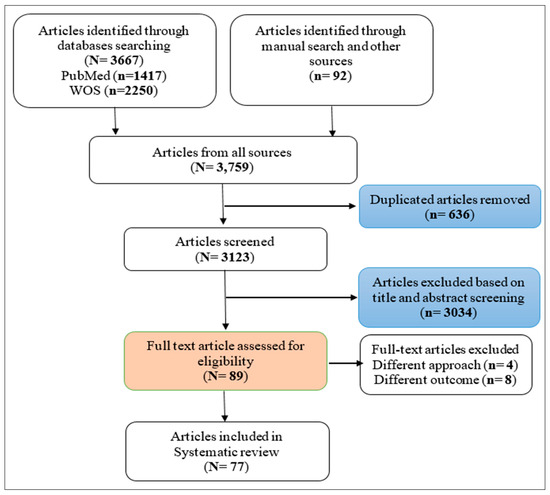

This review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [26]. Prior to sorting the studies for inclusion, the review protocol was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021273784). Two databases (PubMed and Web of Science) were searched intensively to identify articles that were related to the MCL system, SNPs, gene variants, and CVDs, T2D, or their risk factors. Those databases were used since they are considered the most fundamental sources of medical research. Search terms and keywords were developed based on the concepts that made up the research question by using the National Library of Medicine’s vocabulary thesaurus, MeSH, as indicated in Supplementary Tables S1–S3. To maximize our search sensitivity, the bibliographies of first hit articles, similar articles to those in PubMed, and articles in Google Scholar, ProQuest, and some related journals were manually screened to cover all published and unpublished related articles. The process of selecting studies is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the included studies.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies published up to 31 May 2023 were included in this review based on the following criteria: (1) at least one gene (with an identified SNV) related to the MCL system was genotyped for all study participants; (2) the genes (with identified SNVs) were associated with CVDs, T2D, or their risk factors; and (3) primary studies were conducted in the English language and on humans only.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies must not have been conducted on psychiatric-related health statuses like schizophrenia or major depressive disorder (MDD). Furthermore, no limitation was created regarding the study type or characteristics of subjects.

2.4. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

Quality assessment for all included studies was conducted using the standard genetic association study quality assessment tool (Q-Genie tool) [27]. Each article was evaluated on a scale of 1–77; the average score of all included articles was 71 (ranging from 52 to 77), which indicates good-quality studies (Supplementary Appendix S1). A preliminary synthesis of the extracted data from the included articles is indicated in Table 1. A thematic analysis was used since it is an appropriate method in the context of a systematic review of heterogeneous data [28]. Independently, two authors completed all of the above steps. In case of any inconsistency, the opinion and advice from a third reviewer was considered.

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

We performed a bioinformatics analysis to annotate and interpret genetic variants and to identify overrepresented biological functions and pathways associated with our identified genes and variant lists. The variant effect prediction (VEP) tool was used to annotate the functional effects of genetic variants [29]. The VEP tool was run with the human genome assembly GRCh38.p13 and the Ensembl transcript database release 109. For the functional annotation and enrichment analysis, the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) tools was used to identify enriched pathways and gene ontology (GO) terms for our gene list [30]. We selected the “Homo sapiens” species database and gene symbol as the gene identifier in DAVID and used the KEGG pathway as the background database. We visualized the enriched terms using a bar plot and performed gene set enrichment analysis using Excel 2019.

3. Results

Of the 3123 articles retrieved, 77 articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in this review. Out of them, seven were related to CVDs; five were related to T2D; six were related to obesity, and one was related to physical activity, as they were considered risk factors for CVDs and T2D; fourteen were associated with smoking and fifteen, with alcohol consumption; and others were related to drug addiction (three on cocaine, ten on heroin, five on opioids, three on amphetamine, and eight on substance abuse), as they can be risk factors for CVDs as well. Regarding the study designs, the majority of the studies were case–control (n = 50), seventeen were cross-sectional, seven were cohort, and three were randomized controlled trials.

Overall, 117,197 participants were included in 77 studies. Out of them, 27,883 were Asian (65.9% were Chinese), 39,727 were European (16% were European Americans), 6248 were African American, and 158 were Hispanic, although ethnicity was either reported as “Other” or not reported for 49,587 participants. A total of 174 SNVs in 69 different genes of the MCL system that were related to CVDs, T2D, and their potential risk factors were identified. Details on the identified genes and SNVs, including their IDs and other genomic features, are provided in Supplementary Appendix S2 and Supplementary Table S4. The findings were analyzed based on their themes (CVDs, T2D, obesity, smoking and nicotine dependence, alcohol dependence, drug addiction, and exercise behavior), which were related to the review question. Significant and non-significant SNVs for each gene are summarized under those thematic headings in Table 2. Notably, the significant SNVs associated with cardiovascular diseases were related to coronary artery disease, hypertension, venous thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and heart rate.

Our systematic review identified a significant association between the COMT gene and various themes related to CVDs, T2D, and their risk factors. The COMT gene was found to be significantly related to hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, obesity, and drug abuse. The rs4680 SNP within the COMT gene was the most frequently reported genetic variant associated with these diseases and their risk factors. This SNP has been shown to affect the activity of the COMT enzyme, which may impact various physiological processes related to CVDs and T2D.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included articles (n = 77).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included articles (n = 77).

| No. | First Author, Year | Country | Risk Factor/Disease | Sample Size (Male) | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adamska-Patruno et al., 2019 [31] | Poland | Obesity | 927 (473) | Case–control |

| 2 | Al-Eitan et al., 2012 [32] | Jordan | Drug use | 460 (220) | Case–control |

| 3 | Aliasghari et al., 2021 [33] | Iran | Obesity | 531 (0) | Case–control |

| 4 | Anney et al., 2007 [34] | Australia | Substance dependence | 815 (–) | Cohort study |

| 5 | Aroche et al., 2020 [35] | Brazil | Crack cocaine addiction | 1069 (605) | Case–control |

| 6 | Avsar et al., 2017 [36] | Turkey | Obesity | 448 (142) | Case–control |

| 7 | Bach et al., 2015 [37] | Germany | Alcohol dependence | 81 (43) | Cross-sectional |

| 8 | Batel et al., 2008 [38] | France | Alcohol dependence | 230 (138) | Case–control |

| 9 | Beuten et al., 2006 [39] | USA | Nicotine dependence | 2037 (668) | Cross-sectional |

| 10 | Beuten et al., 2007 [40] | USA | Nicotine dependence | 2037 (–) | Cohort study |

| 11 | Céspedes et al., 2021 [41] | Brazil | Alcohol dependence | 401 (366) | Case–control |

| 12 | Carr et al., 2014 [42] | USA | Obesity | 245 (119) | Cross-sectional |

| 13 | Clarke et al., 2014 [43] | USA | Opioid and cocaine addiction | 3311 (1554) | Case–control |

| 14 | da Silva Junior et al., 2020 [44] | Brazil | Alcohol dependence | 300 (300) | Case–control |

| 15 | Doehring et al., 2009 [45] | Germany | Opioid dependence | 88 (62) | Case–control |

| 16 | Erlich et al., 2010 [28] | USA | Nicotine and opioid dependence | 505 (153) | Cross-sectional |

| 17 | Fedorenko et al., 2012 [46] | Russia | Alcohol dependence | 501 (501) | Case–control |

| 18 | Fehr et al., 2013 [47] | Germany | Alcohol dependence | 1159 (804) | Case–control |

| 19 | Fernàndez-Castillo et al., 2010 [48] | Spain | Cocaine dependence | 338 (142) | Case–control |

| 20 | Fernàndez-Castillo et al., 2013 [49] | Spain | Cocaine dependence | 914 (755) | Case–control |

| 21 | Flanagan et al., 2006 [50] | USA | Drug addiction (cocaine, alcohol, heroin, methadone, and methamphetamine) | 1024 (–) | Case–control |

| 22 | Ge et al., 2015 [51] | China | Blood pressure and lipid level | 3079 (1864) | Cohort study |

| 23 | Gellekink et al., 2007 [8] | Netherland | Venous thrombosis | 607 (302) | Case–control |

| 24 | Gold et al., 2012 [52] | USA | Smoking cessation | 1217 (553) | RCT |

| 25 | Hall et al., 2014 [53] | USA | CVD, aspirin and vitamin E | 23,273 (0) | RCT |

| 26 | Hall et al., 2016 [54] | USA | T2D | 909 (0) | Cross-sectional |

| 27 | Harrell et al., 2016 [55] | USA | Smoking | 96 (71) | Cross-sectional |

| 28 | Huang et al., 2009 [56] | USA | Nicotine dependence | 2037 (–) | Cohort study |

| 29 | Johnstone et al., 2004 [57] | USA | Smoking behavior | 975 (399) | Cohort study |

| 30 | Joshua WB, 2013 [58] | USA | Obesity and drug abuse | 59 (29) | Cross-sectional |

| 31 | Kaminskaite et al., 2021 [59] | Lithuania | Alcohol dependence | 329 (127) | Case–control |

| 32 | Kishi et al., 2008 [7] | Japan | Meth use disorder | 944 (479) | Case–control |

| 33 | Ko et al., 2012 [60] | China | Atherosclerosis | 1503 (696) | Cross-sectional |

| 34 | Koijam et al., 2021 [61] | India | Heroin dependence | 279 (110) | Case–control |

| 35 | Kring et al., 2009 [62] | Denmark | T2D and obesity | 1557 (1557) | Cross-sectional |

| 36 | Kuo et al., 2018 [63] | China | Amphetamine dependence | 1063 (854) | Case-control |

| 37 | Lachowicz et al., 2020 [64] | Poland | Polysubstance addiction | 601 (601) | Case–control |

| 38 | Landgren et al., 2011 [33] | Sweden | Alcohol dependence | 115 (88) | Case–control |

| 39 | Långberg et al., 2013 [65] | Sweden | Obesity and Type 2 diabetes | 1177 (827) | Case–control |

| 40 | Levran et al., 2015 [66] | USA | Heroin (OD) and cocaine (CD) addictions | 522 (281) | Case–control |

| 41 | Li et al., 2006 [67] | China | Heroin dependence | 420 (–) | Cross-sectional |

| 42 | Li et al., 2016 [68] | China | Heroin addiction | 1080 (–) | Case–control |

| 43 | Lind et al., 2009 [69] | Australia | Alcohol consumption behavior | 305 (305) | Case–control |

| 44 | Lohoff et al., 2009 [70] | USA | Cocaine dependence | 608 (328) | Case–control |

| 45 | Ma et al., 2005 [71] | USA | Nicotine dependence | 2037 (686) | Case–control |

| 46 | Ma et al., 2018 [6] | China | Coronary artery disease | 611 (471) | Case–control |

| 48 | Mattioni et al., 2022 [72] | France | Alcohol use, nicotine, and cannabis dependence | 3056 (1834) | Case–control |

| 47 | Mir et al., 2018 [73] | India | Cardiovascular disease | 200 (96) | Cohort study |

| 49 | Mutschler et al., 2013 [74] | Germany | Smoking behavior | 551 (–) | Case–control |

| 50 | Najafabadi et al., 2005 [75] | Iran | Opium dependence | 230 (230) | Case–control |

| 51 | Nelson et al., 2014 [76] | USA and Australia | Heroin dependence | 3485 (2095) | Case–control |

| 52 | Noble et al., 1994 [77] | USA | Smoking | 354 (190) | Case–control |

| 53 | Peng et al., 2013 [78] | China | Heroin dependence | 844 (436) | Case–control |

| 54 | Perez de los Cobos et al., 2007 [79] | Spain | Heroin dependence | 426 (305) | Case–control |

| 55 | Prado-Lima et al., 2004 [80] | Brazil | Smoking behaviors | 625 (266) | Cross-sectional |

| 56 | Ragia et al., 2013 [81] | Greek | Smoking initiation | 410 (215) | Case–control |

| 57 | Ragia et al., 2016 [82] | Turkey | Alcohol dependence | 146 (111) | Case–control |

| 58 | Schacht et al., 2009 [9] | USA | Smoking marijuana | 40 (30) | Cross-sectional |

| 59 | Schacht et al., 2022 [83] | USA | Alcohol dependence | 87 (33) | RCT |

| 60 | Shiels et al., 2009 [84] | USA | Smoking | 10,059 (3873) | Cross-sectional |

| 61 | Sipe, et al., 2002 [85] | USA | Drug users (drugs, alcohol, nicotine) | 2881 (–) | Case–control |

| 62 | Spitta et al., 2022 [86] | Germany | Alcohol dependence | 29 (26) | Case–control |

| 63 | Suchankova et al., 2015 [87] | USA | Alcohol dependence | 2671 (2405) | Case–control |

| 64 | Sun et al., 2021 [88] | China | Methamphetamine, heroin, and alcohol addiction | 6146 (4364) | Case–control |

| 65 | Tyndale et al., 2006 [89] | Canada | Drug addiction | 749 (242) | Cross-sectional |

| 66 | Van Der Mee et al., 2018 [90] | Greece | Exercise behavior | 12,929 (5144) | Cohort study |

| 67 | Vereczkei et al., 2013 [91] | Hungary | Heroin dependence | 858 (597) | Case–control |

| 68 | Voisey et al., 2011 [92] | Australia | Alcohol, nicotine, and opiate dependence | 748 (443) | Case–control |

| 69 | Wang et al., 2018 [93] | China | Coronary artery disease | 707 (311) | Case–control |

| 70 | Wei et al., 2012 [94] | China | Nicotine dependence | 480 (480) | Cross-sectional |

| 71 | Xie et al., 2013 [95] | China | Heroin addiction | 533 (533) | Case–control |

| 72 | Xiu et al., 2015 [96] | China | Type 2 diabetes | 1320 (758) | Case–control |

| 73 | Xu et al., 2004 [97] | Germany and China | Heroin dependence | 1462 (–) | Case–control |

| 74 | Ying et al., 2009 [98] | China | Obesity | 426 (217) | Case–control |

| 75 | Yu et al., 2006 [99] | USA | Nicotine dependence | 1590 (730) | Cross-sectional |

| 76 | Zain et al., 2015 [100] | Pakistan | Type 2 diabetes | 191 (107) | Cross-sectional |

| 77 | Zhu et al., 2013 [101] | China | Opioid dependence | 939 (343 *) | Case–control |

| Total number of participants (accumulative) | 117,197 (43,839) | ||||

* = Number of males available for cases only, – = no data available on gender, RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Table 2.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms encoding proteins of the MCL system that are related to cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and their risk factors.

Table 2.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms encoding proteins of the MCL system that are related to cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and their risk factors.

| No. | Risk Factor/Disease | Gene Name ‡ | Significant SNVs † | Non-Significant SNVs † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) | AP2A2 | rs7396366 [6] | |

| BZRAP1 | rs2526378 [93] | |||

| COMT | rs4680 [51,53,60,73] Haplotype: rs2097603–rs4633–rs4680–rs174699 (G–C–G–T) [8] rs4633 [60] rs4818 [53] | (rs2097603 rs4633 rs174699) [8] Haplotypes: rs2097603–rs4633–rs4680–rs174699 (A–C-G–T, A–T-A–T, A–C–G–C) [8] | ||

| FAAH | C385A (rs324420) [9] | |||

| GLP1R | rs4714210 [6] | (rs761387 rs2268635 rs7769547 rs910162 rs3765468 rs3765467 rs3765466 rs10305456 rs10305518 rs1820) [6] | ||

| 2 | Type 2 diabetes (T2D) | 5HT2A | rs6311 [62] | |

| 5HT2C | rs3813929 [62] | |||

| ADRA2A | (rs553668 rs521674) [65] | rs11195419 [65] | ||

| COMT | rs4646312 [96] rs4680 [54,62,96] (900 I/D C) [100] (rs4633 rs4818) [54] | |||

| DRD3 | (rs167771 rs324029 rs8076005 rs20667) [96] | |||

| SLC6A4 | Haplotypes: rs4646312, rs4680 (C–G, T–A) [96] Diplotype: rs4646312–rs4680 (C–G_T–G) SNP–SNP interactions Additive × additive (rs4680 × rs2066713) Dominant × dominant (rs4680 × rs2066713) [11] | Haplotypes: rs8076005, rs2066713 (A–A, A–G, G–G) [96] | ||

| 3 | Obesity | 5HT2AR | –c.1438 A>G [98] | |

| 5HT2C | Combined genotype with COMT (rs3813929 rs4680) [62] | |||

| ANNK1 | rs1800497 [33] | |||

| ADRA2A | (rs553668 rs521674) [65] | rs11195419 [65] | ||

| COMT | rs4680 [62] | rs4580 [42] | ||

| DAT1 | rs28363170 [42] | |||

| DBH | (rs77905 rs6271 rs1611115 rs1108580) [42] | |||

| DDC | (rs2060762 rs11575543 rs11575542 rs11575522 rs11238131) [42] | |||

| DRD1 | rs4532 [42] | |||

| DRD2 | rs1799732 [33] | rs1800497 [42] (rs1800498 rs6277) [72] | ||

| DRD3 | rs6280 [42] | |||

| DRD4 | rs4646984 [42] | |||

| HTR1A | (rs6295 rs1800044 rs1799920 rs10042486) [42] | |||

| HTR1B | (rs6296 rs13212041 rs130058) [42] | |||

| HTR2A | rs6314 [42] | (rs927544 rs7997012 rs6313 rs6311 rs2770296 rs1923886) [42] | ||

| LEPR | rs1137100 [58] | rs1137101 [58] | ||

| MAOA | MAOA-LPR (3.5R/4R) [42] u VNTR [36] | |||

| MC4R | (rs1350341 rs17782313 rs633265) [31] | |||

| OPRD | (rs569356 rs2236861 rs204076 rs7773995 rs514980 rs2281617 rs1799971 rs12205732 rs10485057 rs17174801) [42] | |||

| SERT | (rs2066713 rs2020933 rs16965628 rs1042173) [42] | |||

| SPR | (rs2421095 rs1876487) [42] | |||

| TH | rs71029110 [42] | |||

| TPH2 | (rs7963720 rs7305115 rs4290270 rs17110690 rs1487275 rs17110747) [42] | |||

| 4 | Smoking and nicotine dependence | 5HT2A | T102C [80] | |

| ANKK1 | (rs11604671 rs2734849) [56] | (rs10891545 rs7945132 rs4938013 rs7118900 rs1800497) [56] | ||

| CHRNA3 | (rs660652 rs1051730) [28] | (rs6495308 rs12443170) [28] | ||

| CHRNA4 | rs2236196 [94] | |||

| CHRNA5 | (DRD2/5-HT2CR –759C>T genotype combinations: A1–/–759T–, A1+/–759T–, A1–/–759T + A1+/–759T+; DRD2/5-HT2CR –697G>C genotype combinations: A1–/–697C–, A1+/–697C–, A1–/–697C+ A1+/–697C+, 5-HT2CR –759C>T; interaction of 5-HT2CR –759C>T and DRD2 TaqIA; 5-HT2CR –697G>C; interaction of 5-HT2CR –697G>C and DRD2 TaqIA) [28] (rs936460 rs936461 rs12280580) [55] | rs16969968 [28] | ||

| CHRNB3 | rs4954 [94] rs660652 [28] | |||

| COMT | rs4680 [39,84] (rs740603 rs4680 rs174699 rs933271 rs174699) [39] Haplotype: rs740603–rs4680–rs174699 (A–G–T) rs933271–rs4680–rs174699 (T–G–T, C–A–T) [39] | rs4633 [39] rs4680 [74] | ||

| DBH | rs77905 [84] | |||

| DDC | rs11575461 [94] (rs12718541 rs1470747 rs11238214 rs2060761) [99] rs921451 [71,99] Haplotype: rs921451–rs3735273–rs1451371–rs2060762 (T–G–T–G) rs921451–rs3735273–rs1451371–rs3757472 (T–G–T–G) [71] | (rs11575542 rs732215 rs1451371 rs3823674 rs1470750 rs11575334 rs4947644) [99] (rs998850 rs3735273 rs1470750 rs1451371 rs732215 rs3757472 rs2060762) [71] | ||

| DRD2 | (rs11214613 rs6589377) [94] TaqIA1 [77] | (rs6278 rs6279 rs1079594 rs6275 rs2075654 rs2587548 rs2075652 rs1079596 rs4586205 rs7125415 rs4648318 rs4274224 rs7131056 rs4648317 rs4350392 rs6589377) [56] C32806T [57] (rs1800498 rs6277) [72] | ||

| DRD3 | rs2630351 [94] | |||

| DRD4 | (rs936460 rs936461 rs12280580) [55] | rs1805186 [55] | ||

| DRD5 | rs1967550 [94] | |||

| FIGNL1 | rs10230343 [99] | |||

| GABBR2 | rs2779562 [40] | |||

| GALR1 | rs2717162 [52] | |||

| GRB10 | (rs12669770 rs12540874 rs2715129) [99] | |||

| MAOA | rs1801291 [84] | |||

| MAP3K4 | rs2314378 [94] | |||

| PPP1R1B | Haplotype: rs2271309–rs907094–rs3764352–rs3817160 (–C–T–G–C) rs879606 [40] | rs1874228 [40] | ||

| ZNFN1A1 | (rs11980407 rs1110701) [99] | |||

| 5 | Alcohol dependence | ADH1B | rs1229984 [88] | |

| AGBL4 | rs147247472 [88] | |||

| ANKK1 | rs1800497 [59] (rs4938015 rs1800497) [72,86] | |||

| ANKS1B | rs2133896 [88] | |||

| CHRNA3 | (rs6495307 rs1317286 rs12443170 rs8042059) [34] | |||

| CHRNA4 | (rs1044396 snp12284 rs6011776 rs6010918) [34] | |||

| CHRNA6 | (rs17621710 rs10087172 rs10109429 rs2196129 rs16891604) [34] | |||

| CHRNB2 | (rs2072659 rs2072660) [34] | |||

| CHRNB3 | rs13261190 [34] | (rs62518216 rs62518217 rs62518218 rs16891561) [34] | ||

| COMT | (rs165774 rs4680) [59,83] Haplotype: rs4680–rs165774 (–A–A) [92] | (rs4633 rs740602 rs4818 rs4680 rs4646315) [41] | ||

| CRH | rs6999100 [58] | |||

| CSNK1E | rs135745 [58] | |||

| CTNNA2 | rs10196867 [88] | |||

| DDC | rs11575457 [41] | (rs5884156 rs4490786 rs11575457 rs58085392 rs2876829 rs11575375 rs3735273 rs6950777 rs6264) [41] | ||

| DAT1 | (rs6350 rs463379) [69] | (rs10064219 rs12516948 rs40184 rs6347 rs464049 rs403636) [69] | ||

| DRD1 | rs686 [38] (rs2283265 rs1076560 rs2075654 rs1125394 rs2734836 rs1799732) [32] Haplotype: rs686–rs4532 (–T–G) [38] | (rs686 rs155417 rs4532) [41] | ||

| DRD2 | (rs6277 rs1800498) [72] | A2/A1 [82] rs1800497 [34] (rs6277 rs6275 rs1076560 rs35352421 rs11608185 rs12808482) [41] | ||

| DRD3 | Ser9Gly [82] (rs149281192 rs2251177 rs3732783 rs6280) [41] | |||

| DRD4 | rs7124601 | |||

| DRD5 | (rs2076907 rs6283 rs1967551) [41] | |||

| DβH | 1021 C/T [82] | |||

| FAAH | 385 C/A [85] | |||

| GHRL | (rs42451 rs35680) [34] | (rs4684677 rs34911341 rs696217 rs26802) [34] | ||

| GHSR | rs495225 [34] | (rs2948694 rs572169 rs2232165) [34] | ||

| GLP1R | (rs7766663 rs2235868 rs7769547 rs10305512 rs2143734 rs2268650 rs874900 rs6923761 rs7341356 rs932443 rs2300613) [87] | (rs7738586 rs9296274 rs2268657 rs3799707 rs3799707 rs910170 rs1042044 rs12204668 rs1076733 rs2268640 rs2206942 rs10305514 rs4714210 rs4254984 rs9968886) [87] | ||

| GRIK1 | rs2832407 [82] | |||

| HTR2A | (rs6313 rs6311) [44] | |||

| OPRM1 | rs1799971 [37] | A118G [82] | ||

| PIP4K2A | (rs746203 rs2230469) [46] | (rs8341 rs943190 rs1132816 rs1417374 rs11013052) [46] | ||

| SLC6A3 | (rs429699 rs8179029 rs6347 rs6348 rs460000 rs465130 rs465989 rs13189021 rs2254408 rs2270914 rs2270913 rs8179023 rs6350) [41] | |||

| TH | (rs6578990 rs12419447 rs6357 rs7925924 rs4074905 rs6356 rs7925375) [41] | |||

| VMAT2 | rs363387 [47] Haplotypes: rs363332, rs363387 (–G–T, –G–G) rs363387–rs363333 (–T–T) rs363333–rs363334 (C–T) rs363387–rs363333–rs363334 (–T–T–C) rs363332–rs363387–rs363333–rs363334 (–G–T–T–C) [47] | (rs363371 rs363324 rs11197931) [47] | ||

| 6 | Drug addiction | ADH1B | rs1229984 [88] | |

| AGBL4 | rs147247472 [88] | |||

| ANKK1 | (rs877137 rs877138 rs12360992 rs4938013 rs2734849 rs2734848) [76] rs1800497 [45,91] | rs1800497 [76] rs7118900 [66] | ||

| ANKS1B | rs2133896 [88] | |||

| CDNF | (rs11259365 rs7094179 rs7900873 rs2278871) [70] | |||

| CHRM5 | rs7162140 [102] | (rs661968 257A>T rs2702309 rs2702304 rs2576302 rs2705353) [102] | ||

| CHRNA4 | (rs755203 rs2273506 rs2273505 rs3787141 rs3787140 rs2273504 rs2273502 rs2273501 rs1044396 rs1044397 rs3787137 rs2236196 rs4522666) [7] | |||

| CHRNA5 | rs16969968 [35] Haplotypes: rs16969968–rs660652–rs1051730–rs6495308–rs12443170 (A–G–A–T–G, G–G–G–T–G)) [28] (rs588765 rs514743) [35] | |||

| CHRNB2 | (rs4845652 rs2072658 rs2072659 rs2072660 rs3811450) [7] | |||

| CNTFR | rs7036351 [49] | |||

| COMT | rs4680 [66] | rs4680 [91] (rs933271 rs2239393 rs4818) [66] (rs265981 rs1800497 VNTR 130–166 bp rs2519152 VNTR) [90] | ||

| CSNK1E | rs5757037 [66] | |||

| CTNNA2 | rs10196867 [88] | |||

| DAT1 | Int8 VNTR [48] (rs28363170 rs3836790 rs246997) [61] | SLC6A3 VNTR [67] 3′UTR VNTR [48] (rs40184 rs27048 rs37021 rs250683 rs250682 rs427284) rs458609) [61] | ||

| DBH | rs6479643 [49] | rs1611115 [95] rs1108580 [66] 1021C>T [81] (rs1108580 5UTR ins/del) [48] rs2519152 [90] | ||

| DCC | (rs16956878 rs12607853 rs2292043) [68] | (rs2122822 rs2329341) [66] (rs17753970 rs934345 rs2229080) [68] | ||

| DLG2 | (rs575050, rs2512676, rs17145219, rs2507850) [68] | |||

| DRD1 | (rs4532 rs686) [101] | (rs4532 rs5326 rs2168631 rs6882300 rs267418) [78] (rs686 rs5326) [66] (rs10078866 rs10063995 rs5326 rs1799914 rs4867798) [101] rs265981 [90] | ||

| DRD2 | TaqI A1 [67,75,79] (rs2234689 rs1554929 rs2440390 rs1076563) [76] rs1079597 [91] rs1076560 [43,45] (241 A>G; TaqIB A>G; TaqID G>A; and intron 4 T>C) [97] (759 C>T; 697 G>C) [81] Haplotypes: rs1076560, rs1800498, rs1079597, rs6276, and rs180049 of the ANKK1 (C–T–G–A–T, C–T–G–A–C) [64] | rs7125415 [76] (141 ins/del C; intron 6 ins/del G; 311 Ser>Cys; 20236 C>T; exon 822640 C>G; and TaqIA G>A) [97] rs1800498 [72,91] (rs1076560 rs2283265 rs2587548 rs1076563 rs1079596 rs1125394 rs2471857 rs4648318 rs4274224 rs1799978) [66] TaqIA [81] rs1079597 [48] rs1800497 [48,90] (rs12364283 rs1799978 rs1799732 rs4648317 rs1800496 rs1801028 rs6275 rs6277) [45,72] | ||

| DRD3 | Haplotype: rs324029–rs6280–rs9825563 (A–T–A) rs2134655–rs963468–rs9880168 (A–T–A) [63] | (rs3773678 rs167771) [66] rs6280 [90] (rs2046496 rs2630351) [63] | ||

| DRD4 | rs1800955 [91] | (rs936462 rs747302) [91] VNTR 48 bp [90] | ||

| DRD5 | DRP (A9/A9) [67] rs2867383 [66] VNTR 130–166 bp [90] | |||

| FAAH | (rs12075550 rs6658556 796A>G rs932816 rs4660930) [50] | 385 C/A * [50,89] | ||

| FAT3 | (rs10765565 rs4753069 rs2197678 rs7927604) [68] | |||

| HTR1E | rs1408449 [49] | |||

| HTR2A | (rs6561332 rs6561333) [49] | |||

| KTN1 | (rs10146870 rs1138345 rs10483647 rs1951890 rs17128657 rs945270) [68] | |||

| NCAM1 | (rs4492854 rs587761) [76] | rs11214546 [76] | ||

| NGFR | rs534561 [49] | |||

| NTF3 | rs4073543 [49] | |||

| NTRK2 | rs1147193 [49] | |||

| NTRK3 | (rs12595249 rs744994 rs998636) [49] | |||

| TH | rs2070762 [49] | |||

| TTC12 | (rs2303380 rs10891536 rs4938009 rs7130431 rs12804573) [76] | rs719804 [76] | ||

| 7 | Exercise Behavior | COMT | rs4680 [90] | |

| DAT1 | VNTR 440 bp [90] | |||

| DBH | rs2519152 [90] | |||

| DRD1 | rs265981 [90] | |||

| DRD2/ANKK1 | rs1800497 [90] | |||

| DRD3 | rs6280 [90] | |||

| DRD4 | VNTR 48 bp (7r) [90] | |||

| DRD5 | VNTR 130–166 bp [90] | |||

| MAOA | VNTR 30 bp [90] |

‡ A concise summary of the role of each gene and the chromosome where it is located is provided in Supplementary Table S4, † “Significant” denotes SNVs with a statistically significant association with CVDs, T2D, and/or their risk factors, while “Non-Significant” indicates SNVs without a statistically significant association, * significant with regular sedative users only.

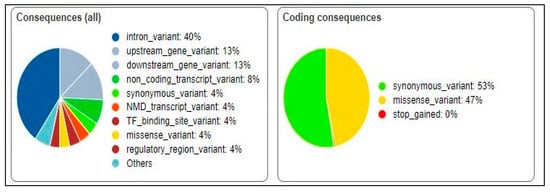

The significant SNVs were analyzed using the VEP tool [29]. The predicted effects of the genetic variants on protein function were synonymous (53%) and missense (47%) (Figure 2). Further analysis of the missense variants using VEP revealed that 48.2% were predicted to be benign, 3.38% were predicted to be likely benign, and 18.42% were predicted to initiate a drug response.

Figure 2.

Predicted effects of genetic variants on protein function.

Moreover, cellular component and functional enrichment analyses of the 69 identified genes were performed using DAVID [30]. For the cellular component enrichment analysis, we found that genes were significantly enriched in several cellular components, including serotonergic and dopaminergic synapses. These results suggest that the 69 genes are involved in various cellular processes and may play important roles in CVDs and T2D development. We also performed a functional enrichment analysis. We found that the 69 genes were significantly enriched in several functional pathways, including “dopamine neurotransmitter receptor activity”, “dopamine binding”, and “serotonin binding”. These pathways are known to be involved in various aspects of CVD and T2D development and progression. The top ten terms for the cellular components, functional enrichments, and phenotypic enrichments of the identified genes are provided in Supplementary Figures S1–S3.

4. Discussion

The MCL system, originating in the VTA region of the brain, is known to affect a person’s adverse health behaviors, which increase their risk for CVDs and T2D development [103,104]. Overstimulation of dopamine, as the main neurotransmitter of the MCL, will lead to craving for different substances, and thus, might be related to increasing the risk of developing CVDs and T2D [9]. Numerous genes in the MCL system have been found to be related to CVDs and T2D, either directly or indirectly, through their involvement in different risky behaviors [8,51,53,54,60,62,73,96]. MCL genes that were frequently found to be associated with multiple traits are discussed herein.

The catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene was found to be significantly related to all themes of this study. The COMT enzyme is encoded by the COMT gene, as it is responsible for the degradation of dopamine–adrenaline and noradrenaline, and catecholamine [73]. Studies show that regulating dopamine activities might have an impact on vascular resistance [73] and numerous reward behaviors like obesity [62]. The rs4680 (Val158Met) of the COMT gene was the most prevalent SNV that was related not only to CVDs [8,51,53,60,73] but also to T2D [54,62,96] and other risk factors [22,39,62,68,76,105]. A case–control study among subjects of European ancestry found no significant association between rs4680 and nicotine dependence when using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [74]. However, the same measurement tool revealed a significant association among two ethnic groups (African American and European American) [39]. Furthermore, a study showed a positive relationship between rs4680 and smoking initiation among females and with smoking persistence among males, as smoking status was self-reported, but not with other smoking behaviors. This variation might be due to the absence of a standard measurement tool for smoking behaviors [39].

In regards to drug addiction and rs4680, two case–control studies [66,91] have shown contradictory results for heroin addiction, even though the same standard instrument (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition) was applied for both. A study revealed that African American descent were genetically susceptible to heroin addiction, as the Val allele of the COMT gene is a risk allele [66]; in contrast, no relationship was found in another study conducted among people of European descent only [91]. These reversing findings might be attributed to the diversity in the ethnic groups and sample sizes of the studies.

A release of mesocorticolimbic dopamine is modulated by a CB1 receptor that is inactivated by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) enzymes, triggering different aspects of addiction [9,50,89]. An SNV variant (rs324420/C385A) of the FAAH gene was found to establish important risk factors for alcohol dependence [50] and marijuana use [9]. Under the recessive model of C385A, it was found to be related to increased heart rate following cannabis smoking [50]. This proved the connection between MCL and drug addiction, which is considered a risk factor for CVDs. However, a study with a larger sample size conducted among adult Caucasians found that a variant of FAAH was not significantly associated with cannabis use [89]. Despite using the same diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder (DSM-IV) in the studies by Schacht et al. [9] and Flanagan et al. [50], the heterogeneity of the sample size, ethnicity, and inclusion criteria might have contributed to the variety in the correlation between the FAAH variant and substance use.

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a hormone that regulates appetite and food intake [6,87], and its receptor activation might affect the reduction in driven behavior for alcohol use [87,106]. GLP-1R in the mesolimbic area is involved in food-related reward processing [6,87]. GLP-1R agonists have a consequence on CVDs through their physiological effects like reduction in fatty acid absorption, increased satiety, and reduction in body weight [6,87]. The risk of coronary artery diseases (CADs) was found to be lower among individuals who carried the GG genotypes of the rs4714210 variant of the GLP-1R gene than for AA genotype carriers [107]; however, another study that addressed the targeted SNVs of GLP-1R for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD) among Caucasians and African Americans indicated no relationship between rs4714210 and AUD [106]. On the other hand, rs7769547 of the GLP-1R gene was significantly associated with AUD [87], but not with that of CADs [6]. This might be due to the fact that different phenotypes were considered; as a consequence, one variant might be a risk for a particular phenotype but not for others.

Different substances such as nicotine, cocaine, alcohol, opiates, and food increase brain dopamine levels and activate the MCL dopaminergic reward pathways of the brain, hence resulting in various risky behaviors such as smoking, alcohol dependence, and obesity [42,67,75,77,79,82,94]. There are five dopamine receptor genes, DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, and DRD5, which are mainly related to different risky behaviors like substance abuse and addiction [32,38,42,55,63,67,75,77,79,90,94,101]. They are considered risk factors for CVDs and T2D. DRD2 TaqI A is an SNV with two variants: A1, the less frequent allele, and A2, the most frequent. The A1 allele is related to a reduction in the concentrations of D2 receptors which results in diverse substance use disorders (SUDs). Studies have identified that TaqI A is significantly associated with smoking [77], heroin [67,79], and opium addiction [75]. On the other hand, Ragia et al. [81] showed no interaction between the DRD2 TaqI A polymorphism and smoking initiation; however, they indicated that an interaction between DRD2 TaqI A1 and 5-HT2CR -759T alleles resulted in smoking initiation behavior [81].

Though the genetic risk factors for CVDs and T2D are abundant, no fundamental study has yet been conducted to study all MCL genetic variants in a comprehensive manner. Intensively studying the impacts of these SNVs on chronic diseases might pave the way for establishing new preventive and treatment approaches. Therefore, this systematic review was conducted to compile worthwhile SNVs encoding proteins of the MCL system that were associated with CVDs and T2D. Although some published studies did not consider ethnicity and gender as cofounders, the available data from the literature seem to designate that the MCL system has a strong relationship with increasing the risk of developing CVDs and T2D, either directly or indirectly through modifying their risk factors. Dimorphisms in gender and ethnicity among the included studies might have contributed to the heterogeneity of the outcomes of this review. Another limitation would be that relying on aggregated data restricted our ability to analyze individual patient data, curtailing detailed insights into specific subpopulations. While our comprehensive search strategy aimed to minimize bias in study selection, it is imperative to acknowledge the underrepresentation of studies in languages other than English. Moreover, interpreting biological causality remains challenging; although our review identified statistically significant associations, establishing causation necessitates a more nuanced understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms. Future research should rigorously explore molecular pathways to enhance comprehension. The generalizability of our findings is inherently constrained by the variations in the included study populations, methodologies, and geographic locations, thereby limiting the external validity of our results. Altogether, further studies using these SNVs might help in developing a better understanding of how these SNVs alter CVDs and T2D.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes15010109/s1, Figure S1: The top ten cellular component enrichment terms of the identified genes; Figure S2: The top ten functional enrichment terms of the identified genes; Figure S3: The top ten phenotypic enrichment terms of the identified genes; Table S1: Keywords used for PubMed search performed on 2023-03-06; Table S2: Search strategy on PubMed; Table S3: Search strategy on Web of Science; Table S4: Gene Catalog: Chromosome Assignment and Functional Roles.

Author Contributions

S.F. was responsible for the conceptualization, supervision, review, and editing of the manuscript. S.N. and M.M. participated equally in the data extraction/curation, analysis, and review. J.S. contributed by reviewing and adding the institutional background information. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Tempus Public Foundation, under the Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship, funded this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Hoy, D.; Rao, C.; Nhung, N.T.T.; Marks, G.; Hoa, N.P. Risk factors for chronic disease in vietnam: A review of the literature. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, 120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Swanson, L.W. The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: A combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 1982, 9, 321–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Buuse, M. Role of The Mesolimbic Dopamine System in Cardiovascular Homeostasis. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1998, 25, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cercato, C.; Fonseca, F.A. Cardiovascular risk and obesity. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lu, R.; Gu, N.; Wei, X.; Bai, G.; Zhang, J.; Deng, R.; Feng, N.; Li, J.; Guo, X. Polymorphisms in the Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Gene Are Associated with the Risk of Coronary Artery Disease in Chinese Han Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Case-Control Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 1054192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, T.; Ikeda, M.; Kitajima, T.; Yamanouchi, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Kawashima, K.; Inada, T.; Harano, M.; Komiyama, T.; Hori, T.; et al. Alpha4 and beta2 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes are not associated with methamphetamine-use disorder in the Japanese population. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1139, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, D.S.; Law, M.; Morris, J.K.; den Heijer, M.; Lewington, S.; Clarke, R.; Clarke, R.; Smith, A.D.; Jobst, K.A.; Czeizel, A.E.; et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype is associated withplasma totalhomocysteine levels andmay increase venous thrombosisrisk. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 98, 756–764. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht, J.P.; Selling, R.E.; Hutchison, K.E. Intermediate cannabis dependence phenotypes and the FAAH C385A variant: An exploratory analysis. Psychopharmacology 2009, 203, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moal, M.; Simon, H.; Burattini, C.; Battistini, G.; Tamagnini, F.; Aicardi, G.; Espejo, E.F.; Miñano, J.; Bengtson, C.P.; Osborne, P.B.; et al. Mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic network: Functional and regulatory roles. Physiol. Rev. 1991, 71, 155–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalivas, P.W.; Sorg, B.A.; Hooks, M.S. The pharmacology and neural circuitry of sensitization to psychostimulants. Behav. Pharmacol. 1993, 4, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abercrombie, E.D.; Keefe, K.A.; DiFrischia, D.S.; Zigmond, M.J. Differential Effect of Stress on In Vivo Dopamine Release in Striatum, Nucleus Accumbens, and Medial Frontal Cortex. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 1655–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitman, M.F.; Wheeler, R.A.; Wightman, R.M.; Carelli, R.M. Selective activation of dopamine transmission in the shell of the nucleus accumbens by stress Peter. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 1376–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornish, J.; Wilks, D.; Buuse, M.v.D. A functional interaction between the mesolimbic dopamine system and vasopressin release in the regulation of blood pressure in conscious rats. Neuroscience 1997, 81, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, O.A.; Devito, J.L.; Astley, C.A. Organization of central nervous system pathways influencing blood pressure responses during emotional behavior. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. Part A Theory Pract. 1984, 6, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kami, K.; Tajima, F.; Senba, E. Activation of mesolimbic reward system via laterodorsal tegmental nucleus and hypothalamus in exercise-induced hypoalgesia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpakov, A.O.; Derkach, K.V.; Berstein, L.M.; Penna, V.; Lipay, M.V.; Duailibi, M.T.; Duailibi, S.E.; Moscato, P.; Santoni, M.; Conti, A.; et al. Brain signaling systems in the Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome: Promising target to treat and prevent these diseases. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhov, I.B.; Derkach, K.V.; Chistyakova, O.V.; Bondareva, V.M.; Shpakov, A.O. Functional state of hypothalamic signaling systems in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with intranasal insulin. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 52, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.M.; Gutierrez, R.; De Araujo, I.E.; Coelho, M.R.P.; Kloth, A.D.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Caron, M.G.; Nicolelis, M.A.L.; Simon, S.A. Dopamine levels modulate the updating of tastant values. Genes Brain Behav. 2007, 6, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wise, R.A. How can drug addiction help us understand obesity? Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainetdinov, R.R. Mesolimbic dopamine in obesity and diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293, R601–R602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Reddy, K.S. Noncommunicable diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, R.; Ee, N.; Peters, J.; Beckett, N.; Booth, A.; Rockwood, K.; Anstey, K.J. Common risk factors for major noncommunicable disease, a systematic overview of reviews and commentary: The implied potential for targeted risk reduction. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Jia, W.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Shen, K.; Wu, S.; Lin, X.; Zhang, G.; et al. Genome-wide search for type 2 diabetes/impaired glucose homeostasis susceptibility genes in the Chinese: Significant linkage to chromosome 6q21-q23 and chromosome 1q21-q24. Diabetes 2004, 53, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Van den Heuvel, D.M.A.; Pasterkamp, R.J. Getting connected in the dopamine system. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008, 85, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (updated August 2023); John Wiley & Sons: Cochrane, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Sohani, Z.N.; Meyre, D.; de Souza, R.J.; Joseph, P.G.; Gandhi, M.; Dennis, B.B.; Norman, G.; Anand, S.S. Assessing the quality of published genetic association studies in meta-analyses: The quality of genetic studies (Q-Genie) tool. BMC Genet. 2015, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlich, P.M.; Hoffman, S.N.; Rukstalis, M.; Han, J.J.; Chu, X.; Kao, W.H.L.; Gerhard, G.S.; Stewart, W.F.; Boscarino, J.A. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes on chromosome 15q25.1 are associated with nicotine and opioid dependence severity. Hum. Genet. 2010, 128, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamska-Patruno, E.; Goscik, J.; Czajkowski, P.; Maliszewska, K.; Ciborowski, M.; Golonko, A.; Wawrusiewicz-Kurylonek, N.; Citko, A.; Waszczeniuk, M.; Kretowski, A.; et al. The MC4R genetic variants are associated with lower visceral fat accumulation and higher postprandial relative increase in carbohydrate utilization in humans. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 2929–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eitan, L.N.; Jaradat, S.A.; Hulse, G.K.; Tay, G.K. Custom genotyping for substance addiction susceptibility genes in Jordanians of Arab descent. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliasghari, F.; Nazm, S.A.; Yasari, S.; Mahdavi, R.; Bonyadi, M. Associations of the ANKK1 and DRD2 gene polymorphisms with overweight, obesity and hedonic hunger among women from the Northwest of Iran. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landgren, S.; Berglund, K.; Jerlhag, E.; Fahlke, C.; Balldin, J.; Berggren, U.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Engel, J.A. Reward-Related Genes and Personality Traits in Alcohol-Dependent Individuals: A Pilot Case Control Study. Neuropsychobiology 2011, 64, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroche, A.P.; Rovaris, D.L.; Grevet, E.H.; Stolf, A.R.; Sanvicente-Vieira, B.; Kessler, F.H.P.; von Diemen, L.; Grassi-Oliveira, R.; Bau, C.H.D.; Schuch, J.B. Association of CHRNA5 Gene Variants with Crack Cocaine Addiction. NeuroMolecular Med. 2020, 22, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, O.; Kuskucu, A.; Sancak, S.; Genc, E. Are dopaminergic genotypes risk factors for eating behavior and obesity in adults? Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 654, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, P.; Vollstädt-Klein, S.; Kirsch, M.; Hoffmann, S.; Jorde, A.; Frank, J.; Charlet, K.; Beck, A.; Heinz, A.; Walter, H.; et al. Increased mesolimbic cue-reactivity in carriers of the mu-opioid-receptor gene OPRM1 A118G polymorphism predicts drinking outcome: A functional imaging study in alcohol dependent subjects. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batel, P.; Houchi, H.; Daoust, M.; Ramoz, N.; Naassila, M.; Gorwood, P. A Haplotype of the DRD1 Gene Is Associated with Alcohol Dependence. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2008, 32, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuten, J.; Payne, T.J.; Ma, J.Z.; Li, M.D. Significant Association of Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) Haplotypes with Nicotine Dependence in Male and Female Smokers of Two Ethnic Populations. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuten, J.; Ma, J.Z.; Lou, X.; Payne, T.J.; Li, M.D. Association analysis of the protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 1B (PPP1R1B) gene with nicotine dependence in European- and African-American smokers. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007, 144, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Céspedes, I.C.; Ota, V.K.; Mazzotti, D.R.; Wscieklica, T.; Conte, R.; Galduróz, J.C.F.; Varela, P.; Pesquero, J.B.; Souza-Formigoni, M.L.O. Association between polymorphism in gene related to the dopamine circuit and motivations for drinking in patients with alcohol use disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, K.A.; Lin, H.; Fletcher, K.D.; Sucheston, L.; Singh, P.K.; Salis, R.J.; Erbe, R.W.; Faith, M.S.; Allison, D.B.; Stice, E.; et al. Two functional serotonin polymorphisms moderate the effect of food reinforcement on BMI. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 127, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.-K.; Weiss, A.R.D.; Ferarro, T.N.; Kampman, K.M.; Dackis, C.A.; Pettinati, H.M.; O’Brien, C.P.; Oslin, D.W.; Lohoff, F.W.; Berrettini, W.H. The Dopamine Receptor D2 (DRD2) SNP rs1076560 is Associated with Opioid Addiction. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2014, 78, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, F.C.d.S.; Araujo, R.M.L.; Sarmento, A.S.C.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Fernandes, H.F.; Yoshioka, F.K.N.; Pinto, G.R.; Motta, F.J.N.; Canalle, R. The association of A-1438G and T102C polymorphisms in HTR2A and 120 bp duplication in DRD4 with alcoholic dependence in a northeastern Brazilian male population. Gene Rep. 2020, 21, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehring, A.; von Hentig, N.; Graff, J.; Salamat, S.; Schmidt, M.; Geisslinger, G.; Harder, S.; Lötsch, J. Genetic variants altering dopamine D2 receptor expression or function modulate the risk of opiate addiction and the dosage requirements of methadone substitution. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2009, 19, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko, O.Y.; Mikhalitskaya, E.V.; Toshchakova, V.A.; Loonen, A.J.M.; Bokhan, N.A.; Ivanova, S.A. Association of PIP4K2A Polymorphisms with Alcohol Use Disorder. Genes 2021, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, C.; Sommerlad, D.; Sander, T.; Anghelescu, I.; Dahmen, N.; Szegedi, A.; Mueller, C.; Zill, P.; Soyka, M.; Preuss, U.W. Association of VMAT2 gene polymorphisms with alcohol dependence. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernàndez-Castillo, N.; Ribasés, M.; Roncero, C.; Casas, M.; Gonzalvo, B.; Cormand, B. Association study between the DAT1, DBH and DRD2 genes and cocaine dependence in a Spanish sample. Psychiatr. Genet. 2010, 20, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernàndez-Castillo, N.; Roncero, C.; Grau-Lopez, L.; Barral, C.; Prat, G.; Rodriguez-Cintas, L.; Sánchez-Mora, C.; Gratacòs, M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.; Casas, M.; et al. Association study of 37 genes related to serotonin and dopamine neurotransmission and neurotrophic factors in cocaine dependence. Genes Brain Behav. 2013, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, J.M.; Gerber, A.L.; Cadet, J.L.; Beutler, E.; Sipe, J.C. The fatty acid amide hydrolase 385 A/A (P129T) variant: Haplotype analysis of an ancient missense mutation and validation of risk for drug addiction. Hum. Genet. 2006, 120, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Wu, H.-Y.; Pan, S.-L.; Huang, L.; Sun, P.; Liang, Q.-H.; Pang, G.-F.; Lv, Z.-P.; Hu, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-W.; et al. COMT Val158Met polymorphism is associated with blood pressure and lipid levels in general families of Bama longevous area in China. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 15055–15064. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, A.B.; Wileyto, E.P.; Lori, A.; Conti, D.; Cubells, J.F.; Lerman, C. Pharmacogenetic Association of the Galanin Receptor (GALR1) SNP rs2717162 with Smoking Cessation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1683–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.T.; Nelson, C.P.; Davis, R.B.; Buring, J.E.; Kirsch, I.; Mittleman, M.A.; Loscalzo, J.; Samani, N.J.; Ridker, P.M.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; et al. Polymorphisms in Catechol-O-methyltransferase Modify Treatment Effects of Aspirin on Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Kathryn. Arter. Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.T.; Jablonski, K.A.; Chen, L.; Harden, M.; Tolkin, B.R.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Bray, G.A.; Ridker, P.M.; Florez, J.C.; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group; et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase association with hemoglobin A1c. Metabolism 2016, 65, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrell, P.T.; Lin, H.-Y.; Park, J.Y.; Blank, M.D.; Drobes, D.J.; Evans, D.E. Dopaminergic genetic variation moderates the effect of nicotine on cigarette reward. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 233, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Huang, W.; Payne, T.J.; Ma, J.Z.; Beuten, J.; Dupont, R.T.; Inohara, N.; Li, M.D. Significant Association of ANKK1 and Detection of a Functional Polymorphism with Nicotine Dependence in an African-American Sample. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, E.C.; Yudkin, P.; Griffiths, S.E.; Fuller, A.; Murphy, M.; Walton, R. The dopamine D2 receptor C32806T polymorphism (DRD2 Taq1A RFLP) exhibits no association with smoking behaviour in a healthy UK population. Addict. Biol. 2004, 9, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshua, W.B. Genetic Influences on the Human Mesolimbic Dopamine Reward System. Hilos Tensados 2010, 1, 1–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskaite, M.; Jokubka, R.; Janaviciute, J.; Lelyte, I.; Sinkariova, L.; Pranckeviciene, A.; Borutaite, V.; Bunevicius, A. Epistatic effect of Ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1–Dopamine receptor D2 and catechol-o-methyltransferase single nucleotide polymorphisms on the risk for hazardous use of alcohol in Lithuanian population. Gene 2021, 765, 145107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.K.C.; Ikeda, S.; Mieno-Naka, M.; Arai, T.A.T.; Zaidi, S.A.H.; Sato, N.; Muramatsu, M.; Sawabe, M. Association of COMT Gene Polymorphisms with Systemic Atherosclerosis in Elderly Japanese. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2012, 19, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koijam, A.S.; Hijam, A.C.; Singh, A.S.; Jaiswal, P.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Rajamma, U.; Haobam, R. Association of Dopamine Transporter Gene with Heroin Dependence in an Indian Subpopulation from Manipur. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kring, S.I.I.; Werge, T.; Holst, C.; Toubro, S.; Astrup, A.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Sørensen, T.I.A. Polymorphisms of Serotonin Receptor 2A and 2C Genes and COMT in Relation to Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.-C.; Yeh, Y.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-C.; Chen, T.-Y.; Yen, C.-H.; Liang, C.-S.; Ho, P.-S.; Lu, R.-B.; Huang, S.-Y. Novelty seeking mediates the effect of DRD3 variation on onset age of amphetamine dependence in Han Chinese population. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 268, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowicz, M.; Chmielowiec, J.; Chmielowiec, K.; Suchanecka, A.; Masiak, J.; Michałowska-Sawczyn, M.; Mroczek, B.; Mierzecki, A.; Ciechanowicz, I.; Grzywacz, A. Significant association of DRD2 and ANKK1 genes with rural heroin dependence and relapse in men. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 27, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Långberg, E.-C.; Ahmed, M.S.; Efendic, S.; Gu, H.F.; Östenson, C.-G. Genetic association of adrenergic receptor alpha 2A with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Obesity 2013, 21, 1720–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levran, O.; Randesi, M.; da Rosa, J.C.; Ott, J.; Rotrosen, J.; Adelson, M.; Kreek, M.J. Overlapping Dopaminergic Pathway Genetic Susceptibility to Heroin and Cocaine Addictions in African Americans. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2015, 79, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Shao, C.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, M.; Lin, L.; Yan, P.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, K.; Jin, L. The effect of dopamine D2, D5 receptor and transporter (SLC6A3) polymorphisms on the cue-elicited heroin craving in Chinese. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2006, 141B, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qiao, X.; Yin, F.; Guo, H.; Huang, X.; Lai, J.; Wei, S. A population-based study of four genes associated with heroin addiction in Han Chinese. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, P.A.; Eriksson, C.P.; Wilhelmsen, K.C. Association between harmful alcohol consumption behavior and dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene polymorphisms in a male Finnish population. Psychiatr. Genet. 2009, 19, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohoff, F.W.; Bloch, P.J.; Ferraro, T.N.; Berrettini, W.H.; Pettinati, H.M.; Dackis, C.A.; O’brien, C.P.; Kampman, K.M.; Oslin, D.W. Association analysis between polymorphisms in the conserved dopamine neurotrophic factor (CDNF) gene and cocaine dependence. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 453, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Z.; Beuten, J.; Payne, T.J.; Dupont, R.T.; Elston, R.C.; Li, M.D. Haplotype analysis indicates an association between the DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) gene and nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, J.; Vansteene, C.; Poupon, D.; Gorwood, P.; Ramoz, N. Associated and intermediate factors between genetic variants of the dopaminergic D2 receptor gene and harmful alcohol use in young adults. Addict. Biol. 2023, 28, e13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, R.; Bhat, M.; Javid, J.; Jha, C.; Saxena, A.; Banu, S. Potential Impact of COMT-rs4680 G > A Gene Polymorphism in Coronary Artery Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2018, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutschler, J.; Abbruzzese, E.; von der Goltz, C.; Dinter, C.; Mobascher, A.; Thiele, H.; Diaz-Lacava, A.; Dahmen, N.; Gallinat, J.; Majic, T.; et al. Lack of Association of a Functional Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Gene Polymorphism with Risk of Tobacco Smoking: Results from a Multicenter Case-Control Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafabadi, M.S.; Ohadi, M.; Joghataie, M.T.; Valaie, F.; Riazalhosseini, Y.; Mostafavi, H.; Mohammadbeigi, F.; Najmabadi, H. Association between the DRD2 A1 allele and opium addiction in the Iranian population. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2005, 134B, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.C.; Lynskey, M.T.; Heath, A.C.; Wray, N.; Agrawal, A.; Shand, F.L.; Henders, A.K.; Wallace, L.; Todorov, A.A.; Schrage, A.J.; et al. ANKK1, TTC12, and NCAM1 Polymorphisms and Heroin Dependence–importance of considering drug exposure Elliot. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 70, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, E.; Ritchie, T.; Syndulko, K.; Jeor, S.; Fitch, R.; Brunner, R.; Sparkes, R. D2 dopamine receptor gene and cigarette smoking: A reward gene? Med. Hypotheses 1994, 42, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Du, J.; Jiang, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, D.; Yu, S.; Zhao, M. The dopamine receptor D1 gene is associated with the length of interval between first heroin use and onset of dependence in Chinese Han heroin addicts. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez de los Cobos, J.; Baiget, M.; Trujols, J.; Sinol, N.; Volpini, V.; Banuls, E.; Calafell, F.; Luquero, E.; del Rio, E.; Alvarez, E. Allelic and genotypic associations of DRD2 TaqI A polymorphism with heroin dependence in Spanish subjects: A case control study. Behav. Brain Funct. 2007, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Prado-Lima, P.A.S.; Chatkin, J.M.; Taufer, M.; Oliveira, G.; Silveira, E.; Neto, C.A.; Haggstram, F.; Bodanese, L.D.; da Cruz, I.B.M. Polymorphism of 5HT2A serotonin receptor gene is implicated in smoking addiction. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 128B, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragia, G.; Iordanidou, M.; Giannakopoulou, E.; Tavridou, A.; Manolopoulos, V.G. Association of DRD2 TaqIA and DβH -1021C>T Gene Polymorphisms with Smoking Initiation and their Interaction with Serotonergic System Gene Polymorphisms. Curr. Pharmacogenom. Pers. Med. 2013, 11, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragia, G.; Veresies, I.; Veresie, L.; Veresies, K.; Manolopoulos, V.G. rs2832407C > A polymorphisms with alcohol DβH −1021C > T, OPRM1 A118G and GRIK1 Association study of DRD2 A2/A1, DRD3 Ser9Gly, dependence. Drug Metab. Pers. Ther. 2016, 31, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacht, J.P.; Im, Y.; Hoffman, M.; Voronin, K.E.; Book, S.W.; Anton, R.F. Effects of pharmacological and genetic regulation of COMT activity in alcohol use disorder: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of tolcapone. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiels, M.S.; Huang, H.Y.; Hoffman, S.C.; Shugart, Y.Y.; Bolton, J.H.; Platz, E.A.; Helzlsouer, K.J.; Alberg, A.J. A Community-Based Study of Cigarette Smoking Behavior in Relation to Variation in Three Genes Involved in Dopamine Metabolism: Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), Dopamine Beta-Hydroxylase (DBH) and Monoamine Oxidase-A (MAO-A). Prev. Med. 2009, 47, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sipe, J.C.; Chiang, K.; Gerber, A.L.; Beutler, E.; Cravatt, B.F. A missense mutation in human fatty acid amide hydrolase associated with problem drug use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 8394–8399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitta, G.; Fliedner, L.E.; Gleich, T.; Zindler, T.; Sebold, M.; Buchert, R.; Heinz, A.; Gallinat, J.; Friedel, E. Association between DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA Allele Status and Striatal Dopamine D2/3 Receptor Availability in Alcohol Use Disorder. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchankova, P.; Yan, J.; Schwandt, M.L.; Stangl, B.L.; Caparelli, E.C.; Momenan, R.; Jerlhag, E.; Engel, J.A.; Hodgkinson, C.A.; Egli, M.; et al. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor as a potential treatment target in alcohol use disorder: Evidence from human genetic association studies and a mouse model of alcohol dependence. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Chang, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Yue, W.; Sun, H.; Ni, Z.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Identification of novel risk loci with shared effects on alcoholism, heroin, and methamphetamine dependence. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndale, R.F.; Payne, J.I.; Gerber, A.L.; Sipe, J.C. The fatty acid amide hydrolase C385A (P129T) missense variant in cannabis users: Studies of drug use and dependence in caucasians. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007, 144B, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Mee, D.J.; Fedko, I.O.; Hottenga, J.-J.; Ehli, E.A.; VAN DER Zee, M.D.; Ligthart, L.; VAN Beijsterveldt, T.C.E.M.; Davies, G.E.; Bartels, M.; Landers, J.G.; et al. Dopaminergic Genetic Variants and Voluntary Externally Paced Exercise Behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereczkei, A.; Demetrovics, Z.; Szekely, A.; Sarkozy, P.; Antal, P.; Szilagyi, A.; Sasvari-Szekely, M.; Barta, C. Multivariate Analysis of Dopaminergic Gene Variants as Risk Factors of Heroin Dependence. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisey, J.; Swagell, C.D.; Hughes, I.P.; Lawford, B.R.; Young, R.M.; Morris, C.P. A novel SNP in COMT is associated with alcohol dependence but not opiate or nicotine dependence: A case control study. Behav. Brain Funct. 2011, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L. A genetic variant near adaptor-related protein complex 2 alpha 2 subunit gene is associated with coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2018, 18, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Chu, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X. Association study of 45 candidate genes in nicotine dependence in Han Chinese. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Zhuang, D.; Zhang, J.; Duan, S.; Zhou, W. Positive association between −1021TT genotype of dopamine beta hydroxylase gene and progressive behavior of injection heroin users. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 541, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, L.; Lin, M.; Liu, W.; Kong, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, P.; Liang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Chen, C.; et al. Association of DRD3, COMT, and SLC6A4 Gene Polymorphisms with Type 2 Diabetes in Southern Chinese: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2015, 17, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Lichtermann, D.; Lipsky, R.H.; Franke, P.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Cao, L.; Schwab, S.G.; Wildenauer, D.B.; Bau, C.H.D.; et al. Association of Specific Haplotypes of D2 Dopamine ReceptorGene with Vulnerability to Heroin Dependence in 2 Distinct Populations. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, S.; Liu, X.-M.; Sun, Y.-M.; Pan, S.-H. Genetic polymorphism c.1438A>G of the 5-HT2A receptor is associated with abdominal obesity in Chinese Northern Han population. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Panhuysen, C.; Kranzler, H.R.; Hesselbrock, V.; Rounsaville, B.; Weiss, R.; Brady, K.; Farrer, L.A.; Gelernter, J. Intronic variants in the dopa decarboxylase (DDC) gene are associated with smoking behavior in European-Americans and African-Americans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2192–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.; Awan, F.R.; Amir, S.; Baig, S.M. A case control association study of COMT gene polymorphism (I/D) with type 2 diabetes and its related factors in Pakistani Punjabi population. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2015, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Yan, C.-X.; Wen, Y.-C.; Wang, J.; Bi, J.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Wei, L.; Gao, C.-G.; Jia, W.; Li, S.-B. Dopamine D1 Receptor Gene Variation Modulates Opioid Dependence Risk by Affecting Transition to Addiction. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anney, R.J.; Lotfi-Miri, M.; Olsson, C.A.; Reid, S.C.; Hemphill, S.A.; Patton, G.C. Variation in the gene coding for the M5 Muscarinic receptor (CHRM5) influences cigarette dose but is not associated with dependence to drugs of addiction: Evidence from a prospective population based cohort study of young adults. BMC Genet. 2007, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemoto, S. Dopamine reward circuitry: Two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens–olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 56, 27–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Wang, H.-L.; Li, X.; Ng, T.H.; Morales, M. Mesocorticolimbic Glutamatergic Pathway. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 8476–8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshchenko, L.G.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Sitlani, C.M.; Ashar, F.N.; Kabir, M.; Biggs, M.L.; Morley, M.P.; Waks, J.W.; Soliman, E.Z.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Genome-Wide Associations of Global Electrical Heterogeneity ECG Phenotype: The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) Study and CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, J.; Kessler, T.; Venegas, L.M.; Schunkert, H. A decade of genome-wide association studies for coronary artery disease: The challenges ahead. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinoff, B. Neurobiologic Processes in Drug Reward and Addiction Bryon. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).