Abstract

Progress in DNA profiling techniques has made it possible to detect even the minimum amount of DNA at a crime scene (i.e., a complete DNA profile can be produced using as little as 100 pg of DNA, equivalent to only 15–20 human cells), leading to new defense strategies. While the evidence of a DNA trace is seldom challenged in court by a defendant’s legal team, concerns are often raised about how the DNA was transferred to the location of the crime. This review aims to provide an up-to-date overview of the experimental work carried out focusing on indirect DNA transfer, analyzing each selected paper, the experimental method, the sampling technique, the extraction protocol, and the main results. Scopus and Web of Science databases were used as the search engines, including 49 papers. Based on the results of this review, one of the factors that influence secondary transfer is the amount of DNA shed by different individuals. Another factor is the type and duration of contact between individuals or objects (generally, more intimate or prolonged contact results in more DNA transfer). A third factor is the nature and quality of the DNA source. However, there are exceptions and variations depending on individual characteristics and environmental conditions. Considering that secondary transfer depends on multiple factors that interact with each other in unpredictable ways, it should be considered a complex and dynamic phenomenon that can affect forensic investigation in various ways, for example, placing a subject at a crime scene who has never been there. Correct methods and protocols are required to detect and prevent secondary transfer from compromising forensic evidence, as well as the correct interpretation through Bayesian networks. In this context, the definition of well-designed experimental studies combined with the use of new forensic techniques could improve our knowledge in this challenging field, reinforcing the value of DNA evidence in criminal trials.

1. Introduction

In forensic investigations, sampling methods play a crucial role in obtaining DNA evidence. The careful collection of samples from crime scenes, victims, and suspects ensures the accuracy and reliability of DNA analysis [1]. At the same time, the extraction, quantification, and amplification of DNA from these samples further enhance the investigative process [2]. All these processes are vital as they enable forensic scientists to analyze and compare DNA profiles, aiding in the identification of individuals, linking suspects to crimes, and providing valuable evidence in court proceedings. In recent years, DNA profiling techniques have been developed into highly sensitive tools: to date, it is possible to obtain a complete profile using small quantities of DNA recovered at crime scenes (i.e., a complete DNA profile can be produced using as little as 100 pg of DNA, equivalent to only 15–20 human cells) [3,4,5,6]. In this context, on the one hand, several cold cases have been solved; however, on the other hand, it is possible to obtain a profile of a subject who was never physically at the scene. For these reasons, while defense attorneys rarely challenge the presence of DNA trace evidence (sub-source level) in court, they increasingly question the mechanisms of DNA transfer to the crime scene (activity level) [4,5,6].

The activity level of DNA transfer in criminal cases is of great importance as it has been observed that not only direct transfer of DNA (primary) can be found at a crime scene but also indirect transfer (secondary) from unrelated individuals through potential vectors such as objects or persons. Numerous studies have described this possibility, highlighting the crucial role that DNA transfer can play in criminal investigations [7,8,9,10]. A seminal paper on the possibility of indirect DNA transfer was written by van Oorschot and Jones in 1997 [11]. Fifteen years later, in another research paper on this theme, Daly et al. [12] reinforced the theory of Ladd et al. [13], describing the secondary transfer of DNA in two possible ways: from skin to skin to object or from the skin to object to skin.

Based on Locard’s exchange principle, which could be summarized with the sentence “every contact leaves a trace” [14], during a crime scene investigation (CSI), trace DNA may be collected from a suspected handled surface/object; based on a recent review, the so-called “touch DNA” could be composed of cell-free DNA, fragment-associated residual DNA, transferred exogenous nucleated cells, endogenous nucleated cells, or anucleate corneocytes [15,16,17,18]. The ability to release “touch DNA” may be subject-related. The first part of the research evaluated the ability to shed trace DNA, and forensic researchers concluded that a subject could be classified as a ‘good shedder’ or ‘poor/bad shedder’ [19,20]. Further studies clarified that on ‘shedder status’, not two but three categories of status should be used: high, intermediate, and low shedder [21,22].

In this scenario, numerous scientific works have investigated the phenomenon of ‘touch DNA’; however, the possibility of generating a ‘secondary transfer’ still remains a challenging scientific question that needs further investigation. For this reason, this review aims to provide an up-to-date overview of the experimental work carried out focusing on secondary DNA transfer, analyzing, for each selected paper, the experimental method, the sampling technique, the extraction protocol, and the main results. A critical overview of secondary transfer may be useful in order to define future research lines, filling the gaps in our knowledge in this challenging field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Search Terms and Timeline

A systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [23].

Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) databases were used as the search engines from 1 January 1997 to 20 November 2023. The following keywords were used: (Touch DNA) AND (Secondary DNA Transfer); (Touch DNA) AND (Indirect DNA Transfer); (Touch DNA) AND (Secondary); and (Touch DNA) AND (Indirect). These keywords were searched within “Article title, Abstract, Keywords” for the Scopus database and “Topic” (searching within “Searches title, abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus”) for the WOS database.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For this literature review, only original articles, published in English, were included. On the contrary, articles not in English, reviews, letters, book chapters, conference papers, and notes were excluded in order to include only articles with a full description of the section about materials and methods. Similarly, any full research papers that were captured in the search but did not have this level of detailed method information were also excluded. Moreover, only articles that were in line with the study’s aim of reviewing indirect DNA transfer were analyzed.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

All sources were screened for inclusion at both the title/abstract and full-text stages. All articles were first assessed by F.S.; then, M.S. conducted an independent re-analysis of the selected articles. If there were differing opinions concerning the articles, they were referred to C.P., who evaluated the criteria after reading the articles. Kappa’s statistical test [16] was used to gauge the level of agreement between the studies (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.92, demonstrating the strength of agreement between the included articles).

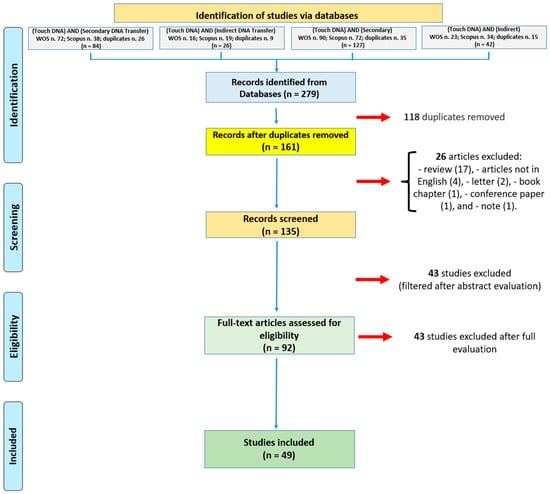

2.4. Characteristics of Eligible Studies

As summarized in Figure 1, a total of 279 articles were obtained from the used databases. Of these, 118 duplicates were removed (using the automatic tool included in the Scopus database), and 26 studies were removed based on the exclusion criteria. Forty-three papers were then removed after abstract screening. After conducting a thorough evaluation, from the pool of 92 articles, 43 studies were excluded as they were not in line with the study’s aim. Ultimately, 49 articles were deemed suitable for the current systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating included and excluded studies in this systematic review.

3. Results

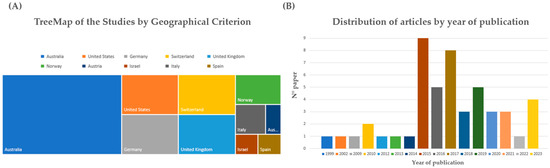

As summarized in Figure 2A, based on the first author’s affiliation, the research groups that contributed to the selected articles came from Australia (21), the United States (5), Germany (5), Switzerland (5), the United Kingdom (5), Norway (3), Italy (2), Austria (1), Israel (1), and Spain (1). Analyzing the distribution of articles by year of publication (Figure 2B), the first paper on indirect DNA transfer that included sufficient method details was published in 1999, while many studies were performed in the last seven years: 2002 (1), 2009 (1), 2010 (2), 2012 (1), 2013 (1), 2014 (1), 2015 (9), 2016 (5), 2017 (8), 2018 (3), 2019 (5), 2020 (3), 2021 (3), 2022 (1), and 2023 (4).

Figure 2.

(A) TreeMap of the studies classified by geographical criterion. The distribution is based on the nationality affiliation of the first author of the study. (B) Distribution of articles by year of publication. The majority of the studies were published in the last seven years.

The experimental model and the main results of the selected articles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The experimental method and the main results are summarized for each selected article.

3.1. Technical Results

Analyzing the main technical data (sampling method, DNA extraction, quantification, amplification), it is important to remark that all selected articles were performed over a wide period from 1999 to 2023, more than 20 years. In this period, forensic genetics constantly improved their methods, offering more sensitive and specific technologies that revolutionized this forensic field [61,62,63]. In general, the summarized results refer to DNA extraction, quantification, and amplification and are strictly related to the period when the study was performed (a study performed in 1999 did not have the possibility to use the same technologies as a study performed in 2023). The sampling method, the DNA extraction protocol, and the quantification and amplification techniques are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The sampling technique, the extraction protocol, and the quantification and amplification techniques are summarized for each selected article.

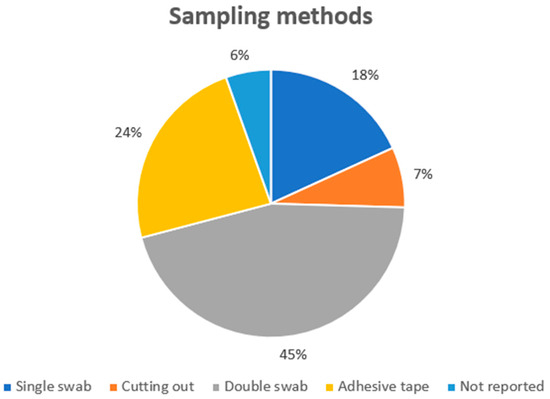

Analyzing the sampling techniques (Figure 3), the most used technique to collect biological samples was the double swab (it was used in 25 cases), while the single swab was used in 10 experimental models. Adhesive tape was used in 13 cases, while cutting-out was used in four cases. Finally, three papers did not report the sampling method. The use of the double swab technique was justified by the experimental model: the main goal of each study was to focus on the secondary transfer generated after a touch. As reported in the literature and confirmed in this review, to sample skin cells, the single/double swab techniques, or adhesive tape, are the best methods to guarantee adequate cell recovery [16,71,72]. Moreover, the cutting-out technique could be applied in selected experimental models (i.e., garment sampling), considering that it may not always be used on hard surfaces. Regarding the sampling methods, a recent literature review concluded that the single-swab method showed the highest efficiency in touch DNA recovery in a wide variety of experimental settings [16].

Figure 3.

The sampling techniques applied in the selected studies.

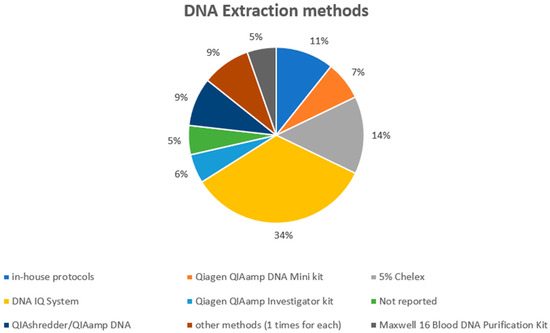

Regarding DNA extraction (Figure 4), the DNA IQ System was the most used method (applied in 19 experimental models), followed by 5% Chelex (used in eight studies), while in-house protocols were applied in seven experimental models. The QIAshredder/QIAamp DNA extraction procedure was applied in five experimental models. Qiagen QIAamp DNA Mini kit (4), Qiagen QIAamp Investigator kit (3), Maxwell 16 Blood DNA Purification Kit (3), Qiagen DNA all-tissue DNA kit (1), “First-DNA” kit (2), PrepFiler Automated Forensic DNA Extraction Kit (1), and Speedtools DNA (1) were the techniques used in the other experimental articles. In three cases, the authors did not indicate the extraction protocol, while in six cases an “in-house method” was used. In a recent research article [71], it has been demonstrated that swabs and direct PCR could positively influence the DNA profiling from a touched item, reducing the number of required cells.

Figure 4.

The DNA extraction methods applied in the selected studies.

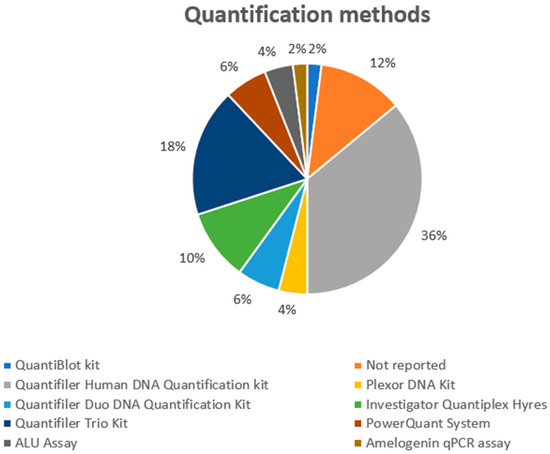

Analyzing the quantification tool (Figure 5), in two articles, three quantification techniques were used in each, while a quantification technique was not used in two research articles; moreover, this information was not included in six experimental models. The kits used are listed below: Quantifiler Human DNA Quantification Kit was used in 18 studies, while Quantifiler Trio DNA Quantification Kit was applied in nine protocols. Quantifiler Duo DNA Quantification Kit (3), Investigator Quantiplex HYres (5), PowerQuant System (4), ALU assay (2), Plexor DNA Quantification Kit (2), QuantiBlot Kit (1), and Investigator Quantiplex Kit (5) were the other methods used. As previously described, modern techniques could improve profiling by applying direct PCR after swab sampling [71]. On the other hand, the use of quantification methods that may evaluate the quantification between male and female DNA, are very useful in the evaluation of activity level.

Figure 5.

The DNA quantification methods applied in the selected studies.

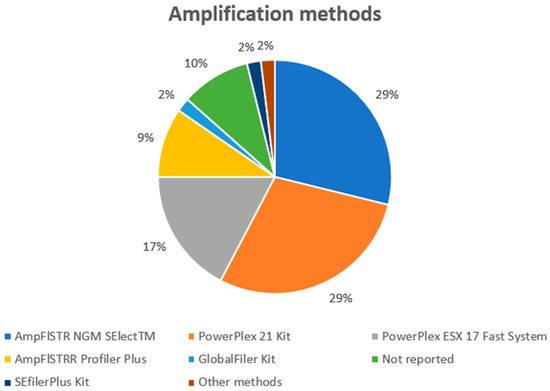

To perform genotyping (Figure 6), the most used kits were AmpFlSTR NGM SElectTM and PowerPlex 21 Kit (15), PowerPlex ESX 17 Fast System kit (10), AmpFlSTRR Profiler Plus (5), SEfilerPlus kit (1), and GlobalFiler (1). In one case, the authors reported that at least one of the following DNA amplification kits was used: AmpflSTR SGM Plus, SEFiler Plus, NGM Select (Life Technologies), PowerPlex ESX 17, ESI 17 (Promega), AmpflSTR Yfiler, or AmpflSTR Yfiler PLUS (Life Technologies) [48]. Finally, in four experimental models, the authors did not provide this information.

Figure 6.

The amplification techniques used in the selected studies.

3.2. Main Findings

In the first paper published about secondary transfer, Ladd et al. [13] analyzed two possible ways to obtain a secondary transfer: skin to skin to object (handshaking) and skin to object to skin. Based on their results, the authors concluded that secondary transfer should be considered a very unusual event. Lowe et al. [24], in one of the first papers that investigated secondary transfer, reported that shedders may be distinguished into good and poor shedders and that secondary transfer (hand to hand to object) is more probable when the time interval is shorter. These authors concluded that secondary transfer under optimized conditions is possible and may result in a single full profile. As regards this concept, to date, shedder status no longer uses two categories of status but three: low, intermediate, and high shedder [21,22]. Szkuta et al. [54] reported the possibility of transferring DNA from the hand of a known contributor to another hand after a handshake, which could be subsequently transferred to, and detected on, a surface contacted by the depositor 40 min to 5 h post handshake. Jones et al. [41] demonstrated that it was possible to transfer DNA to a waistband and outside the front of underwear worn by a male following staged nonintimate social contact, while it is well described that intimate contact allows DNA transfer from the penis to underpants. Goray and van Oorschot [33] described that during daily activities, DNA may be transferred from one object to another, and in particular cases, the hand may be considered to be an indirect vector of the same DNA. Montpetit and O’Donnell [35] reported the possibility of finding foreign DNA on a cartridge after a gunshot, demonstrating the possibility of secondary transfer. Undoubtedly, the recovered touch DNA from fired cartridges is increasing thanks to the new technologies applied to forensic investigations both in sampling and profiling [73].

Szkuta et al. [38] demonstrated that secondary transfer is a possible event during laboratory procedures, demonstrating the potential for inter- and intra-exhibit contamination through further contacts. The same research group investigated different scenarios confirming the possibility of secondary transfer [37]. Goray et al. published two papers on the theme of secondary transfer, experimenting with different situations [25,26]. Their works were very important in clarifying several important aspects. Particularly, they clarified the importance of biological fluids in order to evaluate the possibility of the second transfer and the freshness of deposition; moreover, in the case of skin cells, it is important to evaluate the surfaces of the first and the second items. Moreover, they concluded that the secondary transfer is significantly influenced by the moisture content (i.e., in the case of wet substrates), item substrate type, and manner of contact (passive and pressure contact). In 2017, Szkuta et al. [50] reported that there was no correlation between the duration of handwashing and the extent to which self-DNA was transferred to the handprints of the depositors themselves or to those of the individuals who shook their hands. Taylor et al. [44] demonstrated in their experimental model that secondary transfer is a possible event in the workplace. They demonstrated that the DNA of individuals can be found in areas they do not frequent. This last event could be considered very hazardous because in similar cases it could be very difficult to establish if the subject is involved in a crime. Similarly, Onofri et al. [69] reported the possibility of a secondary transfer at a workplace from an object to another object, simulating a DNA transfer by means of the surface of a credit card. Considering that they found that the DNA transferred could be found as a major contributor, they justified their findings based on the surface (hard and non-porous surface), the time since deposition (fresh trace), and the type of contact (slight pressure and friction). According to Fonneløp et al. [31], it was demonstrated that DNA from the original user of computer equipment, such as a keyboard or mouse, can be transferred to the hands of a subsequent user up to eight days after receiving the items. Oldoni et al. [36] focused on the first and second handler of different items, reporting that after 120 min of handling or wearing objects, the majority of DNA found belonged to the second user. Despite this, the study focused on the first and second handlers, and the authors concluded that there is the possibility of an indirect transfer considering that they found external contributors. Cale et al. [40] described the effectiveness of secondary transfer on items, reporting that the texture of the item handled does not have a significant effect on DNA transfer. In line with these data, Fonneløp et al. [45] described the possibility of detecting foreign DNA on a t-shirt normally used without direct contact, demonstrating a secondary transfer from items. This probability was confirmed by Taylor et al. [52] and Samie et al. [43]. Obviously, the possibility to obtain a complete profile starting from a few cells thanks to new techniques has improved the possibility of detecting foreign DNA on an item that has never been touched.

McColl et al. [46] reported on the possibility of transferring saliva traces from one item to another item by hand, even if it is strictly related to different areas of the hand (i.e., palm, first finger).

Wiegand et al. [27] demonstrated the possibility of a secondary transfer from dried stains to gloves to other items, although it occurred under particular conditions. In this way, Neuhuber et al. [48] reported the possibility of a secondary transfer mediated by police officers during the detection or the analysis of items located at the crime scene. Indeed, as demonstrated by Thornbury et al. [65], indirect DNA transfer without physical contact with dried biological materials from various substrates is a possible event. Nevertheless, Tanzhaus et al. [64] demonstrated that although secondary transfer may be a possible reason for DNA to be found at a crime scene, it is a highly improbable event. A similar study was performed by Fonneløp et al. [32]: these authors showed that there are good and bad transfer items, as well as humans. Regarding the transfer condition, Warshauer et al. [28] reported that secondary transfer is more probable when biological fluid is not completely dried. In another study, Lehmann et al. [29] concluded that transfer is strictly related to the different items’ composition (for example, glass transferred better compared to other surfaces). In another study, Zoppis et al. [30] determined that transfer is more probable in relation to the body zone previously touched (i.e., sebaceous vs. non-sebaceous skin areas). Romero-García et al., 2019 [59], reported that hand washing can possibly reduce the amount of DNA deposited on items. Champion et al., 2019 [57], described the possibility of visualizing the cellular transfer through new applications such as fluorescent Diamond Dye (DD). The use of DD could be important because it does not influence DNA recovery. Otten et al., 2019 [58], reported the possibility of having a secondary transfer at a crime scene via working gloves, considering the shedder status of the suspect. Butcher et al. [56] described that for the analyzed item (knife), the regular user deposited significantly higher quantities of DNA than the second user and unknown sources, irrespective of contact duration. These results are in contrast with a similar study conducted by Pfeifer and Wiegand, 2017 [49], which concluded that the outcome depends mainly on the nature of the contact, the handle material, and user-specific characteristics. In accordance with this study, Gosch et al. [61] investigated four firearm handling scenarios, simulating different actions of the shooter. The amount of DNA after indirect transfer was strictly related to handling conditions and surface types of areas of the firearm. It is important to highlight the nature of the surface and the sampling techniques applied.

The study conducted by Oldoni et al. [42] found that an increase in second contact duration led to an overall negative correlation in the relative contribution of DNA between first and second users. Various unmonitored factors such as hand-washing frequency, previous object-handling activities, and the variable manner of contact can influence secondary transfer. Obviously, as remarked by Meakin et al. [47], when indirect transfer occurs, it decreases with increasing time between DNA deposition and recovery.

Recently, Verdon et al. [39] investigated sampling techniques, concluding that there is no clear sampling method preference when attempting to differentially sample deposits of touch DNA layered over a pre-existing DNA background.

To investigate different scenarios, Voskoboinik et al. [55] tested the potential of laundry to generate DNA transfer, ascertaining the possibility of a secondary transfer through shared washing and mixing of new and used garments. These new data are in contrast with the results obtained by Kamphausen et al. [34]: in their experimental model, these authors demonstrated a possible secondary transfer between dirty clothes with biological fluids (i.e., blood cells) to another item, while they concluded that the secondary transfer generated from skin cells during a washing process is improbable. Ruan et al. [53] confirmed the opportunity for DNA transfer during regular laundry activities, demonstrating the opportunity for the acquisition of endogenous and foreign DNA during this process. Szkuta et al. [51] investigated the possibility of transferring trace DNA by reusing fingerprint brushes.

According to the experiments conducted by Szkuta et al., DNA transfer can occur during daily activities. The studies found that DNA from the person wearing a garment can accumulate in external areas, and individuals sharing the same space with the wearer can also contribute their DNA to the garment. In some cases, the wearer’s contribution may be minor or absent compared to their close associates, depending on the specific situation and the area of the garment [60,63]. Despite these important data, according to Samie et al. [62], the amount of DNA present on an item is primarily influenced by the handler’s deposition. They also found that in cases of secondary transfer, where the subject only touches the handler’s hand and not the object directly, the subject’s DNA was a minor contributor to the mixed profiles. Recently, Thornbury et al. [66] confirmed the possibility of a secondary transfer without physical contact from used clothing, e.g., through shaking. Similarly, Reither et al. [67] investigated two possible scenarios, demonstrating that an indirect DNA transfer could occur from clothing to flooring and from flooring to clothing in both ‘active’ and ‘passive’ situations, even if the DNA transfer was greater in active simulation. Interestingly, Monkman et al. [70] demonstrated that a domestic animal (in their experimental model they used a dog) could be a vector for human DNA transfer, demonstrating a transfer from the animal to a gloved hand during patting and a bed sheet while walking.

Carrara et al. [7] recently performed an experiment to investigate the possibility of generating an indirect transfer in burglary simulations, confirming this alarming event. McCrane and Mulligan [68] confirmed the possibility of an indirect transfer in their experimental model. In this study, a male and a female alternately held a pistol, and subsequently, the female’s hand was swabbed, demonstrating a secondary transfer. The study applied only a quantitative method to confirm the indirect transfer.

4. Discussion

Secondary DNA transfer is the process of transferring DNA from one object or person to another through an intermediary. For example, if two people shake hands and then one of them touches a knife, the DNA of the first person may be transferred to the knife through the second person. This phenomenon can have implications for forensic investigations as it can link innocent individuals to crime scenes or introduce foreign DNA to forensic samples. As previously described (Figure 2A), most of the articles (21 out of 49) were written by researchers from Australia, followed by the United States (5), Germany (5), Switzerland (5), and the United Kingdom (5). The other countries that had at least one article were Norway (3), Italy (2), Austria (1), Israel (1), and Spain (1). Despite the fact that this review focused only on research papers that have sufficiently detailed method sections, these results suggest that major efforts have been made by countries with common law legal systems; moreover, several countries such as Italy and Spain should improve their efforts in this challenging field. Analyzing Figure 2B, the research on secondary transfer DNA has increased in recent years, especially since 2015. The first article, with a description of the experimental model, was published in 1999, but only four more articles were published until 2010. From 2010 to 2023, there were 44 articles published, with the peak years being 2015 (9 articles), 2017 (8 articles), and 2019 and 2016 (5 articles). These data confirm that secondary transfer DNA is an emerging and relevant topic in forensic science, with a diverse and growing body of literature.

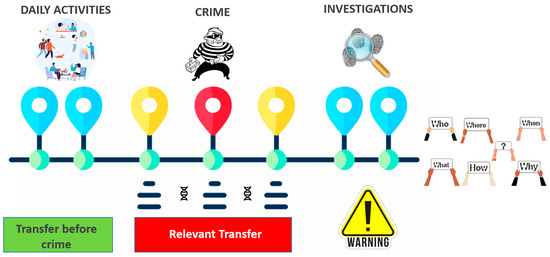

As demonstrated in all experimental models, DNA transfer can occur anywhere during daily activities. This event becomes relevant in the case of a crime or when items are collected at a crime scene (Figure 7). Several cases of indirect transfer that had occurred in real criminal investigations were reported by Neuhuber et al. [48] who described indirect transfers via a camera, a car, and a desk, demonstrating the importance of being aware of this undesirable event.

Figure 7.

DNA can be transferred during various daily activities (green bar), but it is only significant when it comes to a crime involving items or persons. Different considerations must be made if the transfer takes place during a crime (red bar). Lastly, the transfer may be an unwelcome event during crime scene investigation or lab activities (warning), although it may be controlled following rigorous protocols.

In the last seven years, advancements have been made in genetic investigations in forensic sciences with the possibility of obtaining a complete DNA profile [32,74,75] and a forensic DNA phenotyping panel using massive parallel sequencing [76,77,78] with a small number of cells. In this context, the forensic laboratory has to establish the nature of the trace [79] as well as define reliable methods to establish the time since deposition [80]. To establish the nature of the trace and the time since deposition, transcriptome sequencing combined with biostatistical algorithms may be very useful in forensic cases [81,82,83,84]. Moreover, it is fundamental to clarify all aspects of indirect transfer as much as possible. Overall, the importance of sampling methods and the subsequent analysis of DNA cannot be neglected in forensic investigations as they serve as crucial tools in the pursuit of justice. As suggested by McCrane and Mulligan [68], using an inexpensive experimental model that does not require extensive technical expertise, it is possible to improve data in this research field, allowing for the participation of a wide range of laboratories and investigating a broad range of variables that could affect DNA transfer events.

Based on the results of the present review, in accordance with previous published reviews [85,86,87,88], the following variables should be considered in the evaluation of DNA transfer:

- The presence of DNA background: This refers to the amount and source of DNA that is already present on an object or surface before contact. A high DNA background can mask or dilute the secondary transfer, making it less likely to be detected [25,28,33,35,44,48,58,89].

- The subject’s characteristics: These include age, sex, shedder status (good or bad), and lifestyle habits. Some people tend to shed more DNA than others, which can affect the amount of DNA transferred and detected. Age and sex can also influence the quality and quantity of DNA, as well as lifestyle habits such as smoking, drinking, or using cosmetics [24,49,50,56,58,62].

- The type and duration of the contact: The type of contact can be direct (touching) or indirect (through an intermediary). The duration of contact can range from seconds to hours. Generally, direct and longer contacts are more likely to result in secondary DNA transfer than indirect and shorter contacts [24,29,32,36,40,43,55,57,63,69].

- The body zone previously touched: different body zones have different amounts and types of cells that can shed DNA, such as skin cells, sweat glands, hair follicles, or saliva glands. For example, touching the face or mouth can transfer more DNA than touching the arm or leg [30,34,38,40,59,61].

- The characteristics of the item: These include material, usage, size, shape, texture, and cleanliness. Different materials have different affinities for DNA, such as cotton being more absorbent than plastic. Usage can affect the amount of DNA background on an item, such as a frequently used phone having more DNA than a rarely used pen. Size, shape, and texture can affect the surface area and roughness of an item, which can influence the amount of contact and friction between the item and the DNA source. Cleanliness can affect the presence of contaminants or inhibitors that can degrade or interfere with DNA analysis [7,25,26,31,32,33,37,42,45,46,50,51,53,55,57,58,60,64,66,69].

- Trace type: This refers to whether the trace is fresh or dry, visible or invisible, single-source or mixed-source. Fresh traces are more likely to contain viable cells that can be amplified by PCR than dry traces. Visible traces are easier to locate and collect than invisible traces. Single-source traces are easier to interpret than mixed-source traces that contain DNA from multiple contributors [27,28,29,34,38,39,47,50,51,53,65,66,69].

- The activities made before contact: These include washing hands, wearing gloves, handling other items, or performing other actions that can affect the amount and quality of DNA on the hands or other body parts. Washing hands can reduce the amount of DNA available for transfer. Wearing gloves can prevent direct contact between the source and the target of DNA transfer. Handling other items can introduce additional sources of DNA or contaminants that can affect the analysis [30,33,34,38,40,59,61,63,68].

These factors are not exhaustive and may interact with each other in complex ways.

Other factors that could influence DNA transfer and its recovery are as follows:

- Time: The period of time between the primary and secondary contact and the interval between the secondary contact and the sampling of the evidence can affect the amount and quality of DNA transferred. Generally, the longer the time gap, the lower the chance of detecting secondary transfer DNA. However, there is no clear consensus on how long DNA can persist on different surfaces or objects after secondary transfer [36,38,40,41,42,46,54,56,63].

- Environmental conditions: The temperature, humidity, presence of microbial contamination, and other environmental factors can influence the degradation and persistence of DNA after secondary transfer. For example, high temperature and humidity can accelerate DNA degradation, while low temperature and humidity can preserve DNA for longer periods. Microbial contamination can also degrade DNA or interfere with its detection [32,33,37,41,44,47,52,53,60,65,68].

- Technical methods: The sampling methods, extraction methods, and profiling techniques used in forensic analysis can also affect the detection and interpretation of secondary transfer DNA. For example, different sampling methods (such as swabbing, taping, or cutting) can yield different amounts of DNA from the same surface or object. Different extraction methods (such as organic, Chelex, or silica-based) can be more efficient in isolating DNA from complex mixtures. Different profiling techniques (such as STRs, SNPs, or NGS) can have different sensitivities and specificities in amplifying and analyzing DNA from low-template DNA or degraded samples [38,39,42,48,52].

With this literature review, we aimed to clarify several important aspects of the techniques that could be used in order to improve results in this research field. On the contrary, we are unable to perform a data analysis of the analysis of the included papers because the experimental models are too varied and affected by different flaws. For example, several experiments did not perform the T0 swab on the hand/palm of the handler to verify the presence of exogenous DNA before starting the experimentation. As recently reported by Bini et al. [90], the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer could reduce DNA transfer.

Based on these findings, DNA transfer remains challenging in forensic science, both in case evaluations and in court testimony. Considering the results of this review that show the problems related to indirect transfer, it is more probable to obtain a DNA mixture from a piece of evidence. To assign the probability of DNA results, given competing propositions that specify the mechanisms of transfer, several factors must be considered to develop Bayesian networks to define DNA movement through complex transfer scenarios [91,92,93]. In this way, the analysis of biological traces found at crime scenes can rule out/include a possible suspect, providing a numerical estimate of the similarity between crime scene DNA and that of the suspect, obtaining a relatively high confidence score [94]. In this regard, in order to assess the value of forensic biological evidence, the DNA Commission of the International Society for Forensic Genetics (ISFG) published international guidelines highlighting the importance of activity-level propositions [95]. Nevertheless, as recently remarked by Kotsoglou and McCartney [96], the focus is on analyzing and assessing evidence shifts from the source to the activity, moving one step higher on the inferential ladder. This shift includes considering the mechanics of how the DNA sample was deposited, despite the fact that a significant portion of determining evidential sufficiency relies on establishing the source, which is the initial step in the hierarchy of propositions (source–activity–offense). This exercise is challenging, and the question remains whether a jury can draw a reasonable adverse inference. For these purposes, machine learning could be an optimal tool to evaluate the number of contributors in mixed profiles [97], as well as in the evaluation of complex Bayesian networks [91]. As regards these considerations, it should be taken into account that to date, the court is not always prepared to receive and interpret this kind of report to give the right “weight of evidence”. Recently, Morgan [98] reported that there is a call for forensic science to return to a scientific approach. The integration of legal requirements and research into forensic science practice and policy is seen as crucial. This author reported the importance of situating evidence within the entire forensic science process, developing an evidence base for each stage, and understanding the interaction of different lines of evidence. Earwaker et al. [99] remarked on this concept, confirming that it is necessary to minimize the misinterpretation of scientific evidence and maximize the effectiveness of crime reconstruction approaches and their application within the criminal justice system.

In this scenario, there are several open questions: how, when, and in which manner did the DNA arrive at a crime scene? First, laboratory personnel are called on to apply their skills to obtain DNA profiles starting from biological evidence, reducing/erasing potential contamination at every step. Individual hairs, sweat, and/or saliva inadvertently deposited by an investigator at a crime scene or during laboratory activities could cost valuable time, creating the risk of excluding a valid suspect, as well as misinterpreting physical evidence. In this context, indirect DNA transfer (also called secondary, tertiary, etc., transfer) of biological material via multiple steps (i.e., hand → hand → items, hand → item → hand, etc.) represents an event that could damage irremediably the investigation. Indeed, direct contamination could be limited by adopting the exclusion database containing reference profiles of subjects (police officers, healthcare personnel, etc.) involved in the CSI for automatic elimination, while its absence could favor contamination accidents [48]. This error, in addition to irreparably compromising the investigation, could lead to the conviction of a subject who was never at the scene, as pointed out by Tanzhaus et al. [64]. To eliminate both risks of contamination, the number of people present at the crime scene should be limited to well-trained personnel. Given that the potential for contamination of evidence (or the crime scene) increases as the number of people accessing the crime scene increases, there is an increasing need for the crime scene to be secured quickly by isolating and restricting access to it.

Another crucial aspect is the possibility that indirect transfer occurs during evidence packaging or laboratory activities [85,87]. New and sterile containers must be used to package all evidence, and the packaging equipment must also be free of contaminants. As largely discussed in this review, secondary transfer is a possible event both among different objects and among the same objects [31]. Indeed, indirect contamination could occur during evidence analysis, for instance at a forensic laboratory. This is another area for potential contamination: particularly, during sampling methods, an involuntary transfer may be carried out with sterile scissors or gloves [37,100]. Despite the presence of standard procedures for decontamination, analysts are aware of the risk of contamination and routinely clean their work areas. To minimize the potential risk of contamination, facilities and forensic scientists usually adopt standard procedures and policies. Therefore, it is crucial to perform decontamination procedures repeatedly during laboratory hours.

In this scenario, the value of DNA evidence in criminal trials should be re-evaluated. Scenarios involving multiple transfer events may increasingly account for the presence of a person’s genetic material at the crime scene. Considering what was previously discussed, the finding of genetic material is no longer sufficient to place that person at the crime scene. Without data on approximate transfer rates based on a set of variables, it is very difficult to estimate the probability of an outcome in each transfer event scenario. Given the paucity of well-designed studies on the matter, in accordance with Gosch and Courts [86], it is desirable that further research should be carried out after extensive literature research in order to understand the well-studied and under-researched transfer scenarios and the relative variables investigated (such as the sampling methods, the extraction protocol, and quantification and amplification kits). In particular, a set of new studies regarding secondary transfer could be focused on the poorly studied aspects, prioritizing the under-represented variables, questions, and scenarios. In this way, the use of ‘DNA-TrAC’ could be very useful as a guiding tool in the preliminary phase of each experimental study, despite the fact that it should be updated.

Lastly, several considerations should be made from an ethical point of view, considering that ethics should be an intrinsic part of a scientist’s daily practice in forensic genetics. Scientists should understand and act within ethical and legal boundaries, incorporating the operational and societal impacts of their daily decisions: particularly, considering indirect transfer as a possible event, every trace should be analyzed with attention [101]. Moreover, the retention of DNA samples and profiles by the police has been a subject of controversy, and this question could be amplified in the context of DNA transfer. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has ruled that the ‘blanket and indiscriminate’ retention of DNA of individuals is disproportionate and breaches the European Convention on Human Rights. Under the new regime, DNA profiles of non-convicted individuals must be deleted after an investigation, with a maximum retention period of five years for those arrested or charged with qualifying offenses. Nevertheless, the impact of these limitations on the effectiveness of forensic DNA analysis remains unknown [102].

This review has several strengths, including a high value for Kappa’s statistical test, a wide temporal period analyzed, a detailed study selection process flowchart, and a comprehensive search methodology. However, there are also some limitations associated with the review. These include the possibility of selected keywords influencing the search strategy, potential influence from the author’s personal viewpoints, the inclusion of articles published only on WOS or Scopus, a small sample size that precludes complete statistical analysis, and gaps in literature searching practices that may be related to the use of selected databases. Moreover, this review included only research papers on indirect transfer that have sufficiently detailed method sections. Finally, it is important to remark that in order to perform a serious meta-analysis of data, the data should be obtained following well-defined procedures. On the contrary, the selected articles were extremely varied in their experimental model and methods, and the results were not always clearly or completely described.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, secondary transfer is a complex and dynamic phenomenon that can affect forensic investigation in various ways. It depends on multiple factors that interact with each other in unpredictable ways. It requires careful methods and protocols to detect and prevent it from compromising forensic evidence. It has serious implications for forensic practice and justice that need to be addressed with awareness and education. The concern of law enforcement and forensic practitioners regarding the risk associated with evidence contamination dates back to the inception of evidence analysis. However, newer forensic analysis techniques have magnified the potential impact of contamination on criminal investigations due to the sensitivity of current forensic DNA analysis. Proper collection, packaging, handling during transport, storage, analysis, as well as decontamination procedures can significantly reduce the potential for contamination. At the same time, the possibility that a transfer occurs during daily activities represents a very hazardous event that could compromise DNA analysis.

In this scenario, the principal take-home message of this review is related to the different flaws of the published experimental models: therefore, it is necessary to highlight the importance of making well-designed studies, diminishing variability, in order to establish a solid scientific base for this insidious topic. The definition of well-designed experimental studies and the use of the most modern extraction and amplification techniques will make it possible to fill those gaps in our knowledge, reinforcing the value of DNA evidence in criminal trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S. and C.P.; methodology, F.S., M.S., G.C., M.E., P.G. and C.P.; software, F.S.; validation, C.P.; formal analysis, F.S.; investigation, F.S.; resources, F.S.; data curation, F.S., M.S., G.C., P.G., M.E. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.S., M.S. and C.P.; visualization, F.S.; supervision, C.P.; project administration, F.S.; funding acquisition, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Scientific Bureau of the University of Catania for language support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bukyya, J.L.; Tejasvi, M.L.A.; Avinash, A.; Chanchala, H.P.; Talwade, P.; Afroz, M.M.; Pokala, A.; Neela, P.K.; Shyamilee, T.K.; Srisha, V. DNA Profiling in Forensic Science: A Review. Glob. Med. Genet. 2021, 8, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, H.; Granja, R. DNA Technologies in Criminal Investigation and Courts BT—Forensic Genetics in the Governance of Crime; Machado, H., Granja, R., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 45–56. ISBN 978-981-15-2429-5. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, K.E.; Miller, J.J. DNA Recovery and Analysis from Skeletal Material in Modern Forensic Contexts. Forensic Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddrill, P.R. Developments in Forensic Dna Analysis. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, D.; Mills, D. Past, Present, and Future of DNA Typing for Analyzing Human and Non-Human Forensic Samples. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 646130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, F.; Onofri, V.; Turchi, C.; Buscemi, L.; Pesaresi, M.; Tagliabracci, A. Past, Present and Future in Forensic Human Identification; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 9783030338329. [Google Scholar]

- Carrara, L.; Hicks, T.; Samie, L.; Taroni, F.; Castella, V. DNA Transfer When Using Gloves in Burglary Simulations. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2023, 63, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckingham, A.K.; Harvey, M.L.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. The Origin of Unknown Source DNA from Touched Objects. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 25, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.; Sessa, F.; Rendine, M.; Spagnolo, L.; De Simone, S.; Riezzo, I.; Ricci, P.; Pascale, N.; Salerno, M.; Bertozzi, G.; et al. A Multidisciplinary Approach Is Mandatory to Solve Complex Crimes: A Case Report. Egypt J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomara, C.; Gianpaolo, D.P.; Monica, S.; Maglietta, F.; Sessa, F.; Guglielmi, G.; Turillazzi, E. “Lupara Bianca” a Way to Hide Cadavers after Mafia Homicides. A Cemetery of Italian Mafia. A Case Study. Leg. Med. 2015, 17, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Jones, M.K.K. DNA Fingerprints from Fingerprints. Nature 1997, 387, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, D.J.; Murphy, C.; McDermott, S.D. The Transfer of Touch DNA from Hands to Glass, Fabric and Wood. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, C.; Adamowicz, M.S.; Bourke, M.T.; Scherczinger, C.A.; Lee, H.C. A Systematic Analysis of Secondary DNA Transfer. J. Forensic Sci. 1999, 44, 1270–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locard, E. The Analysis of Dust Traces. Am. J. Police Sci. 1930, 1, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrill, J.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. A Review of Trace “Touch DNA” Deposits: Variability Factors and an Exploration of Cellular Composition. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 39, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzo, P.; Mazzobel, E.; Marcante, B.; Delicati, A.; Caenazzo, L. Touch DNA Sampling Methods: Efficacy Evaluation and Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Ostrander, J.; Wickenheiser, R.; Hall, A. Touch DNA in Forensic Science: The Use of Laboratory-Created Eccrine Fingerprints to Quantify DNA Loss. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Bertozzi, G.; Messina, G.; Ricci, P.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V.; Cantatore, S.; Turillazzi, E.; Pomara, C. Touch DNA: Impact of Handling Time on Touch Deposit and Evaluation of Different Recovery Techniques: An Experimental Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.; Swensson, M.; Gifvars, E.; Hedell, R.; Forsberg, C.; Ansell, R.; Hedman, J. Individual Shedder Status and the Origin of Touch DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 56, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, F.; Cecati, M.; Pesaresi, M.; Turchi, C.; Carle, F.; Tagliabracci, A. Fingerprints as Evidence for a Genetic Profile: Morphological Study on Fingerprints and Analysis of Exogenous and Individual Factors Affecting DNA Typing. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, H.; Gill, P.; Roseth, A.; Fonneløp, A.E. Determination of Shedder Status: A Comparison of Two Methods Involving Cell Counting in Fingerprints and the DNA Analysis of Handheld Tubes. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 53, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.Y.C.; Tan, J.; Lee, Y.S.; Syn, C.K.C. Shedder Status—An Analysis over Time and Assessment of Various Contributing Factors. J. Forensic Sci. 2023, 68, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.; Murray, C.; Whitaker, J.; Tully, G.; Gill, P. The Propensity of Individuals to Deposit DNA and Secondary Transfer of Low Level DNA from Individuals to Inert Surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. 2002, 129, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goray, M.; Eken, E.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Secondary DNA Transfer of Biological Substances under Varying Test Conditions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2010, 4, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A. Investigation of Secondary DNA Transfer of Skin Cells under Controlled Test Conditions. Leg. Med. 2010, 12, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, P.; Heimbold, C.; Klein, R.; Immel, U.; Stiller, D.; Klintschar, M. Transfer of Biological Stains from Different Surfaces. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2011, 125, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warshauer, D.H.; Marshall, P.; Kelley, S.; King, J.; Budowle, B. An Evaluation of the Transfer of Saliva-Derived DNA. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 126, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, V.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Following the Transfer of DNA: How Far Can It Go? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2013, 4, e53–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppis, S.; Muciaccia, B.; D’Alessio, A.; Ziparo, E.; Vecchiotti, C.; Filippini, A. DNA Fingerprinting Secondary Transfer from Different Skin Areas: Morphological and Genetic Studies. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2014, 11, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonneløp, A.E.; Johannessen, H.; Gill, P. Persistence and Secondary Transfer of DNA from Previous Users of Equipment. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 5, e191–e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonneløp, A.E.; Egeland, T.; Gill, P. Secondary and Subsequent DNA Transfer during Criminal Investigation. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 17, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. The Complexities of DNA Transfer during a Social Setting. Leg. Med. 2015, 17, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamphausen, T.; Fandel, S.B.; Gutmann, J.S.; Bajanowski, T.; Poetsch, M. Everything Clean? Transfer of DNA Traces between Textiles in the Washtub. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 129, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montpetit, S.; O’Donnell, P. An Optimized Procedure for Obtaining DNA from Fired and Unfired Ammunition. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 17, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldoni, F.; Castella, V.; Hall, D. Exploring the Relative DNA Contribution of First and Second Object’s Users on Mock Touch DNA Mixtures. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 5, e300–e301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Harvey, M.L.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA Transfer by Examination Tools—A Risk for Forensic Casework? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 16, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Harvey, M.L.; Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Residual DNA on Examination Tools Following Use. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 5, e495–e497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Preliminary Investigation of Differential Tapelifting for Sampling Forensically Relevant Layered Deposits. Leg. Med. 2021, 17, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cale, C.M.; Earll, M.E.; Latham, K.E.; Bush, G.L. Could Secondary DNA Transfer Falsely Place Someone at the Scene of a Crime? J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Scott, K.; Lewis, J.; Davidson, G.; Allard, J.E.; Lowrie, C.; McBride, B.M.; McKenna, L.; Teppett, G.; Rogers, C.; et al. DNA Transfer through Nonintimate Social Contact. Sci. Justice 2016, 56, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldoni, F.; Castella, V.; Hall, D. Shedding Light on the Relative DNA Contribution of Two Persons Handling the Same Object. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 24, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, L.; Hicks, T.; Castella, V.; Taroni, F. Stabbing Simulations and DNA Transfer. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 22, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.; Abarno, D.; Rowe, E.; Rask-Nielsen, L. Observations of DNA Transfer within an Operational Forensic Biology Laboratory. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 23, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonneløp, A.E.; Ramse, M.; Egeland, T.; Gill, P. The Implications of Shedder Status and Background DNA on Direct and Secondary Transfer in an Attack Scenario. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 29, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McColl, D.L.; Harvey, M.L.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA Transfer by Different Parts of a Hand. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, e29–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, G.E.; Butcher, E.V.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Morgan, R.M. Trace DNA Evidence Dynamics: An Investigation into the Deposition and Persistence of Directly- and Indirectly-Transferred DNA on Regularly-Used Knives. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 29, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhuber, F.; Kreindl, G.; Kastinger, T.; Dunkelmann, B.; Zahrer, W.; Cemper-Kiesslich, J.; Grießner, I. Police Officer’s DNA on Crime Scene Samples—Indirect Transfer as a Source of Contamination and Its Database-Assisted Detection in Austria. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, e608–e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, C.M.; Wiegand, P. Persistence of Touch DNA on Burglary-Related Tools. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2017, 131, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szkuta, B.; Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Transfer and Persistence of DNA on the Hands and the Influence of Activities Performed. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 28, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Ballantyne, K.N. DNA Decontamination of Fingerprint Brushes. Forensic Sci. Int. 2017, 277, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.; Biedermann, A.; Samie, L.; Pun, K.-M.; Hicks, T.; Champod, C. Helping to Distinguish Primary from Secondary Transfer Events for Trace DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 28, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, T.; Barash, M.; Gunn, P.; Bruce, D. Investigation of DNA Transfer onto Clothing during Regular Daily Activities. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Kokshoorn, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Transfer and Persistence of Non-Self DNA on Hands over Time: Using Empirical Data to Evaluate DNA Evidence given Activity Level Propositions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 33, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskoboinik, L.; Amiel, M.; Reshef, A.; Gafny, R.; Barash, M. Laundry in a Washing Machine as a Mediator of Secondary and Tertiary DNA Transfer. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, E.V.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Morgan, R.M.; Meakin, G.E. Opportunistic Crimes: Evaluation of DNA from Regularly-Used Knives after a Brief Use by a Different Person. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 42, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Linacre, A. Visualising DNA Transfer: Latent DNA Detection Using Diamond Dye. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 7, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, L.; Banken, S.; Schürenkamp, M.; Schulze-Johann, K.; Sibbing, U.; Pfeiffer, H.; Vennemann, M. Secondary DNA Transfer by Working Gloves. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 43, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-García, C.; Rosell-Herrera, R.; Revilla, C.J.; Baeza-Richer, C.; Gomes, C.; Palomo-Díez, S.; Arroyo-Pardo, E.; López-Parra, A.M. Effect of the Activity in Secondary Transfer of DNA Profiles. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 7, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Ansell, R.; Boiso, L.; Connolly, E.; Kloosterman, A.D.; Kokshoorn, B.; McKenna, L.G.; Steensma, K.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Assessment of the Transfer, Persistence, Prevalence and Recovery of DNA Traces from Clothing: An Inter-Laboratory Study on Worn Upper Garments. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 42, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosch, A.; Euteneuer, J.; Preuß-Wössner, J.; Courts, C. DNA Transfer to Firearms in Alternative Realistic Handling Scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 48, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, L.; Taroni, F.; Champod, C. Estimating the Quantity of Transferred DNA in Primary and Secondary Transfers. Sci. Justice 2020, 60, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Ansell, R.; Boiso, L.; Connolly, E.; Kloosterman, A.D.; Kokshoorn, B.; McKenna, L.G.; Steensma, K.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA Transfer to Worn Upper Garments during Different Activities and Contacts: An Inter-Laboratory Study. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 46, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzhaus, K.; Reiß, M.-T.; Zaspel, T. “I’ve Never Been at the Crime Scene!”—Gloves as Carriers for Secondary DNA Transfer. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornbury, D.; Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Indirect DNA Transfer without Contact from Dried Biological Materials on Various Surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 51, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornbury, D.; Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Transfer of DNA without Contact from Used Clothing, Pillowcases and Towels by Shaking Agitation. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reither, J.B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Szkuta, B. DNA Transfer between Worn Clothing and Flooring Surfaces with Known Histories of Use. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 61, 102765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrane, S.M.; Mulligan, C.J. An Innovative Transfer DNA Experimental Design and QPCR Assay: Protocol and Pilot Study. J. Forensic Sci. 2023, 68, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onofri, M.; Altomare, C.; Severini, S.; Tommolini, F.; Lancia, M.; Carlini, L.; Gambelunghe, C.; Carnevali, E. Direct and Secondary Transfer of Touch DNA on a Credit Card: Evidence Evaluation Given Activity Level Propositions and Application of Bayesian Networks. Genes 2023, 14, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkman, H.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Presence of Human DNA on Household Dogs and Its Bi-Directional Transfer. Genes 2023, 14, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallupurackal, V.; Kummer, S.; Voegeli, P.; Kratzer, A.; Dørum, G.; Haas, C.; Hess, S. Sampling Touch DNA from Human Skin Following Skin-to-Skin Contact in Mock Assault Scenarios—A Comparison of Nine Collection Methods. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzo, P.; Giuliodori, A.; Rodriguez, D.; Caenazzo, L. Effect of Dactyloscopic Powders on DNA Profiling from Enhanced Fingerprints: Results from an Experimental Study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2014, 35, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, F.; Esposito, M.; Roccuzzo, S.; Cocimano, G.; Li Rosi, G.; Sablone, S.; Salerno, M. DNA Profiling from Fired Cartridge Cases: A Literature Review. Minerva Forensic Med. 2023, 143, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, F.; Maglietta, F.; Asmundo, A.; Pomara, C. Forensic Genetics and Genomic. In Forensic and Clinical Forensic Autopsy; Pomara, C., Fineschi, V., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Turchi, C.; Previderè, C.; Bini, C.; Carnevali, E.; Grignani, P.; Manfredi, A.; Melchionda, F.; Onofri, V.; Pelotti, S.; Robino, C.; et al. Assessment of the Precision ID Identity Panel Kit on Challenging Forensic Samples. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 49, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, C.; Onofri, V.; Melchionda, F.; Fattorini, P.; Tagliabracci, A. Development of a Forensic DNA Phenotyping Panel Using Massive Parallel Sequencing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 7, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzo, P.; Politi, C.; Delicati, A.; Gabbin, A.; Caenazzo, L. External Visible Characteristics Prediction through SNPs Analysis in the Forensic Setting: A Review. Front. Biosci. Landmark 2021, 26, 828–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, M.; De Knijff, P. Improving Human Forensics through Advances in Genetics, Genomics and Molecular Biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijen, T.; Harbison, S. On the Identification of Body Fluids and Tissues: A Crucial Link in the Investigation and Solution of Crime. Genes 2021, 12, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lech, K.; Liu, F.; Ackermann, K.; Revell, V.L.; Lao, O.; Skene, D.J.; Kayser, M. Evaluation of MRNA Markers for Estimating Blood Deposition Time: Towards Alibi Testing from Human Forensic Stains with Rhythmic Biomarkers. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 21, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Gondhali, U.; Choudhary, S. Potential of DNA Technique-Based Body Fluid; Springer: Singapore, 2022; ISBN 9789811643187. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, C.; Fleming, R. Partial Validation of Multiplexed Real-Time Quantitative PCR Assays for Forensic Body Fluid Identification. Sci. Justice 2023, 63, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.R.; Lednev, I.K. Crime Clock—Analytical Studies for Approximating Time since Deposition of Bloodstains. Forensic Chem. 2020, 19, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosch, A.; Bhardwaj, A.; Courts, C. TrACES of Time: Transcriptomic Analyses for the Contextualization of Evidential Stains—Identification of RNA Markers for Estimating Time-of-Day of Bloodstain Deposition. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2023, 67, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Szkuta, B.; Meakin, G.E.; Kokshoorn, B.; Goray, M. DNA Transfer in Forensic Science: A Review. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 38, 140–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosch, A.; Courts, C. On DNA Transfer: The Lack and Difficulty of Systematic Research and How to Do It Better. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 40, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Meakin, G.E.; Kokshoorn, B.; Goray, M.; Szkuta, B. DNA Transfer in Forensic Science: Recent Progress towards Meeting Challenges. Genes 2021, 12, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meakin, G.E.; Kokshoorn, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Szkuta, B. Evaluating Forensic DNA Evidence: Connecting the Dots. WIREs Forensic Sci. 2021, 3, e1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Sessa, F.; Cocimano, G.; Zuccarello, P.; Roccuzzo, S.; Salerno, M. Advances in Technologies in Crime Scene Investigation. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bini, C.; Giorgetti, A.; Fazio, G.; Amurri, S.; Pelletti, G.; Pelotti, S. Impact on Touch DNA of an Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer Used in COVID-19 Prevention. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 137, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.; Samie, L.; Champod, C. Using Bayesian Networks to Track DNA Movement through Complex Transfer Scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 42, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taroni, F.; Garbolino, P.; Aitken, C. A Generalised Bayes’ Factor Formula for Evidence Evaluation under Activity Level Propositions: Variations around a Fibres Scenario. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 322, 110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Pomara, C. The Interpretation of Mixed DNA Samples BT—Handbook of DNA Profiling; Dash, H.R., Shrivastava, P., Lorente, J.A., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-981-15-9364-2. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.M.; Kline, M.C.; Coble, M.D. NIST Interlaboratory Studies Involving DNA Mixtures (MIX05 and MIX13): Variation Observed and Lessons Learned. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 37, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.; Hicks, T.; Butler, J.M.; Connolly, E.; Gusmão, L.; Kokshoorn, B.; Morling, N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Parson, W.; Prinz, M.; et al. DNA Commission of the International Society for Forensic Genetics: Assessing the Value of Forensic Biological Evidence—Guidelines Highlighting the Importance of Propositions. Part II: Evaluation of Biological Traces Considering Activity Level Propositions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 44, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsoglou, K.N.; McCartney, C. To the Exclusion of All Others? DNA Profile and Transfer Mechanics—R v Jones (William Francis) [2020] EWCA Crim 1021 (03 Aug 2020). Int. J. Evid. Proof 2021, 25, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, M.S.; Ariëns, S.; Ypma, R.J.F.; Abeel, T.; Benschop, C.C.G. Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Forensics: Realistic Explanations for Number of Contributor Predictions of DNA Profiles. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 56, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.M. Conceptualising Forensic Science and Forensic Reconstruction. Part I: A Conceptual Model. Sci. Justice 2017, 57, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earwaker, H.; Nakhaeizadeh, S.; Smit, N.M.; Morgan, R.M. A Cultural Change to Enable Improved Decision-Making in Forensic Science: A Six Phased Approach. Sci. Justice 2020, 60, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiotta, G.; Tasselli, G.; Tommolini, F.; Lancia, M.; Massetti, S.; Carnevali, E. Risk of DNA Transfer by Gloves in Forensic Casework. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 5, e527–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienroth, M.; Granja, R.; McCartney, C.; Lipphardt, V.; Amoako, E.N. Ethics as Lived Practice. Anticipatory Capacity and Ethical Decision-Making in Forensic Genetics. Genes 2021, 12, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, A.O.; McCartney, C. The Effectiveness of the Current Use of Forensic DNA in Criminal Investigations in England and Wales. WIREs Forensic Sci. 2021, 3, e1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).