13q Deletion Syndrome Involving RB1: Characterization of a New Minimal Critical Region for Psychomotor Delay

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Subjects

2.2. Whole-Genome Array-Based Comparative Genomic (a-CGH)

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Description

3.1.1. Patient 1 (#349/19)

3.1.2. Patient 2 (#82/2013)

3.1.3. Patient 3 (#2148/18)

3.1.4. Patient 4 (#2794/20)

3.1.5. Patients 5–6 (#387–#404)

3.1.6. Patient 7 (#3311/17)

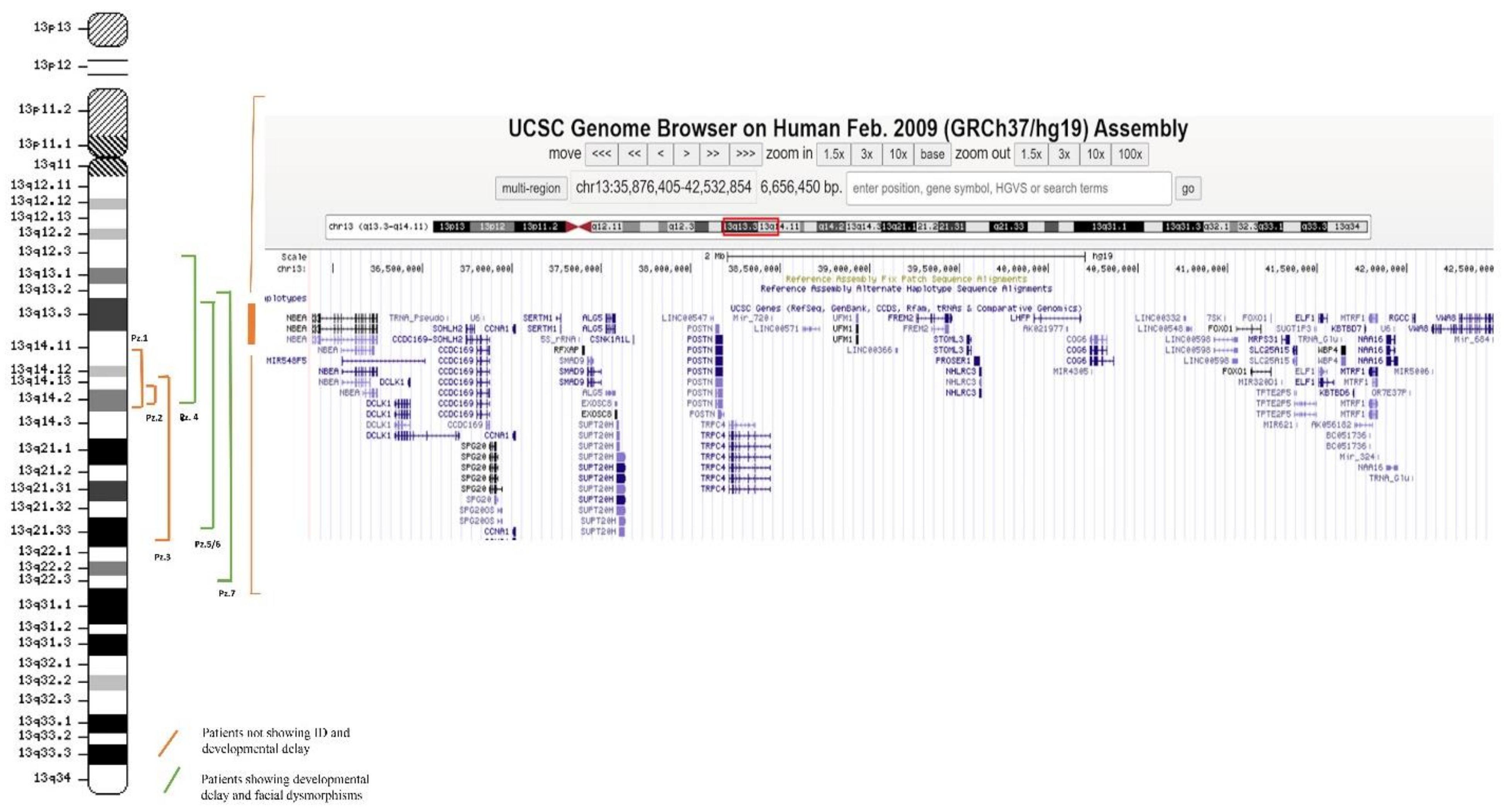

3.2. Molecular Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caselli, R.; Speciale, C.; Pescucci, C.; Uliana, V.; Sampieri, K.; Bruttini, M.; Longo, I.; De Francesco, S.; Pramparo, T.; Zuffardi, O.; et al. Retinoblastoma and mental retardation microdeletion syndrome: Clinical characterization and molecular dissection using array CGH. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 52, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, P.; Ansperger-Rescher, B.; Schüler, A.; Zeschnigk, M.; Gallie, B.; Lohmann, D.R. Spectrum of gross deletions and insertions in the RB1 gene in patients with retinoblastoma and association with phenotypic expression. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, A.; Gavin, M.R.; Luo, R.X.; Dean, D.C. Role of the LXCXE Binding Site in Rb Function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 6799–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kloss, K.; Währisch, P.; Greger, V.; Messmer, E.; Fritze, H.; Höpping, W.; Passarge, E.; Horsthemke, B. Characterization of deletions at the retinoblastoma locus in patients with bilateral retinoblastoma. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1991, 39, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, D.R.; Gallie, B. Retinoblastoma: Revisiting the model prototype of inherited cancer. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 129, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motegi, T.; Kaga, M.; Yanagawa, Y.; Kadowaki, H.; Watanabe, K.; Inoue, A.; Komatsu, M.; Minoda, K. A recognizable pattern of the midface of retinoblastoma patients with interstitial deletion of 13q. Qual. Life Res. 1983, 64, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, O.; Cormier-Daire, V.; Lyonnet, S.; Desjardins, L.; Turleau, C.; Doz, F. Dysmorphic phenotype and neurological impairment in 22 retinoblastoma patients with constitutional cytogenetic 13q deletion. Clin. Genet. 1999, 55, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojinova, R.I.; Schorderet, D.F.; Addor, M.-C.; Gaide, A.-C.; Thonney, F.; Pescia, G.; Nenadov-Beck, M.; Balmer, A.; Munier, F.L. Further delineation of the facial 13q14 deletion syndrome in 13 retinoblastoma patients. Ophthalmic Genet. 2001, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Gersen, S.; Anyane-Yeboa, K.; Warburton, D. Preliminary definition of a “critical region” of chromosome 13 in q32: Report of 14 cases with 13q deletions and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993, 45, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavotinek, A.M.; Lacbawan, F. Large interstitial deletion of chromosome 13q and severe short stature: Clinical report and re-view of the literature. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2003, 12, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, D.; Ullmann, R.; Muradyan, A.; Klein-Hitpaß, L.; Kanber, D.; Ounap, K.; Kaulisch, M.; Lohmann, D. Genotype–phenotype correlations in patients with retinoblastoma and interstitial 13q deletions. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 19, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miura, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Nakagawa, E.; Sasaki, M.; Kurosawa, K.; Inoue, K.; Goto, Y.-I. 13q13.3 microdeletion associated with apparently balanced translocation of 46,XX,t(7;13) suggests NBEA involvement. Brain Dev. 2020, 42, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, K.M.; Thompson, M.L.; Amaral, M.D.; Finnila, C.R.; Hiatt, S.M.; Engel, K.L.; Cochran, J.N.; Brothers, K.B.; East, K.M.; Gray, D.E.; et al. Genomic diagnosis for children with intellectual disability and/or developmental delay. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, Y.; Balice-Gordon, R.J.; Hess, D.M.; Landsman, D.S.; Minarcik, J.; Golden, J.; Hurwitz, I.; Liebhaber, S.A.; Cooke, N.E. Neurobeachin Is Essential for Neuromuscular Synaptic Transmission. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 3627–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrihan, L.; Rohlmann, A.; Fairless, R.; Andrae, J.; Döring, M.; Missler, M.; Zhang, W.; Kilimann, M.W. Neurobeachin, a protein implicated in membrane protein traffic and autism, is required for the formation and functioning of central synapses. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 5095–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.; Altunoglu, U.; Miller, R.; Maroofian, R.; James, K.N.; Caglayan, A.O.; Wu, K.M.; Bakey, Z.; Kayserili, H.; Schmidts, M.; et al. MAB21L1 loss of function causes a syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder with distinctive cerebellar, ocular, craniofacial and genital features (COFG syndrome). J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deuel, T.A.; Liu, J.S.; Corbo, J.; Yoo, S.-Y.; Rorke-Adams, L.B.; Walsh, C.A. Genetic Interactions between Doublecortin and Doublecortin-like Kinase in Neuronal Migration and Axon Outgrowth. Neuron 2006, 49, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koizumi, H.; Tanaka, T.; Gleeson, J.G. doublecortin-like kinase Functions with doublecortin to Mediate Fiber Tract Decussation and Neuronal Migration. Neuron 2006, 49, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, E.; Kashiwagi, Y.; Kuriu, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Koizumi, H.; Gleeson, J.G.; Okabe, S. Doublecortin-like kinase enhances dendritic remodelling and negatively regulates synapse maturation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shu, T.; Tseng, H.; Sapir, T.; Stern, P.; Zhou, Y.; Sanada, K.; Fischer, A.; Coquelle, F.M.; Reiner, O.; Tsai, L. Doublecortin-like kinase controls neurogenesis by regulating mitotic spindles and M phase progression. Neuron 2006, 49, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Håvik, B.; Degenhardt, F.A.; Johansson, S.; Fernandes, C.P.D.; Hinney, A.; Scherag, A.; Lybæk, H.; Djurovic, S.; Christoforou, A.; Ersland, K.M.; et al. DCLK1 variants are associated across schizophrenia and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, J.; Yourshaw, M.; Mamsa, H.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S.; Menezes, M.P.; Hong, J.E.; Leong, D.W.; Senderek, J.; Salman, M.S.; Chitayat, D.; et al. Mutations in the RNA exosome component gene EXOSC3 cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia and spinal motor neuron degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boczonadi, V.; Muller, J.S.; Pyle, A.; Munkley, J.; Dor, T.; Quartararo, J.; Ferrero, I.; Karcagi, V.; Giunta, M.; Polvikoski, T.; et al. EXOSC8 mutations alter mRNA metabolism and cause hypomyelination with spinal muscular atrophy and cerebellar hypoplasia. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, H.; Cross, H.; Proukakis, C.; Hershberger, R.; Bork, P.; Ciccarelli, F.D.; Patton, M.A.; McKusick, V.A.; Crosby, A.H. SPG20 is mutated in Troyer syndrome, an hereditary spastic paraplegia. Nat. Genet. 2002, 31, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, H.E.; McKusick, V.A. The Troyer syndrome. A recessive form of spastic paraplegia with distal muscle wasting. Arch. Neurol. 1967, 16, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Herberg, F.W.; Laue, M.M.; Wüllner, C.; Hu, B.; Petrasch-Parwez, E.; Kilimann, M.W. Neurobeachin: A protein kinase A-anchoring, beige/Chediak-higashi protein homolog implicated in neuronal membrane traffic. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 8551–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrett, S.; Beck, J.C.; Bernier, R.; Bisson, E.; Braun, T.A.; Casavant, T.L.; Childress, D.; Folstein, S.E.; Garcia, M.; Gardiner, M.B.; et al. An autosomal genomic screen for autism. Collaborative linkage study of autism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 88, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steele, M.M.; Al-Adeimi, M.; Siu, V.M.; Fan, Y.-S. Brief report: A case of autism with interstitial deletion of chromosome 13. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritvo, E.R.; Mason-Brothers, A.; Menkes, J.H.; Sparkes, R.S. Association of autism, retinoblastoma, and reduced esterase D activity. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988, 45, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volders, K.; Nuytens, K.; Creemers, J. The autism candidate gene neurobeachin encodes a scaffolding protein implicated in mem-brane trafficking and signaling. Curr. Mol. Med. 2011, 11, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odent, P.; Creemers, J.W.; Bosmans, G.; D’Hooge, R. Spectrum of social alterations in the Neurobeachin haploinsufficiency mouse model of autism. Brain Res. Bull. 2021, 167, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Woodroffe, A.; Smith, R.; Holguin, S.; Martinez, J.; Filipek, P.A.; Modahl, C.; Moore, B.; Bocian, M.E.; Mays, L.; et al. Molecular genetic delineation of a deletion of chromosome 13q12–>q13 in a patient with autism and auditory processing deficits. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2002, 98, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, S.E.; Fitch, D.H.; Kassem, I.A.; Emmons, S.W. Pattern formation in the nematode epidermis: Determination of the arrangement of peripheral sense organs in the C. elegans male tail. Development 1991, 113, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederlund, M.L.; Vendrell, V.; Morrissey, M.E.; Yin, J.; Gaora, P.Ó.; Smyth, V.A.; Higgins, D.G.; Kennedy, B.N. mab21l2 transgenics reveal novel expression patterns of mab21l1 and mab21l2, and conserved promoter regulation without sequence conservation. Dev. Dyn. 2011, 240, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, J.G.; Lin, P.T.; Flanagan, L.A.; Walsh, C. Doublecortin Is a Microtubule-Associated Protein and Is Expressed Widely by Migrating Neurons. Neuron 1999, 23, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Des Portes, V.; Pinard, J.M.; Billuart, P.; Vinet, M.C.; Koulakoff, A.; Carrié, A.; Gelot, A.; Dupuis, E.; Motte, J.; Berwald-Netter, Y.; et al. A novel CNS gene required for neuronal migration and involved in X-linked subcortical laminar heterotopia and lissencephaly syndrome. Cell 1998, 92, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, T.; Serneo, F.F.; Higgins, C.; Gambello, M.J.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Gleeson, J.G. Lis1 and doublecortin function with dynein to mediate coupling of the nucleus to the centrosome in neuronal migration. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 165, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bielas, S.L.; Serneo, F.F.; Chechlacz, M.; Deerinck, T.J.; Perkins, G.A.; Allen, P.B.; Ellisman, M.H.; Gleeson, J.G. Spinophilin facilitates dephosphorylation of doublecortin by PP1 to mediate microtubule bundling at the axonal wrist. Cell 2007, 129, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaar, B.T.; Kinoshita, K.; McConnell, S.K. Doublecortin microtubule affinity is regulated by a balance of kinase and phospha-tase activity at the leading edge of migrating neurons. Neuron 2004, 41, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijkmans, T.F.; Antonia van Hooijdonk, L.W.; Fitzsimons, C.P.; Vreugdenhil, E. The doublecortin gene family and disorders of neuronal structure. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Wang, X.; Beveridge, N.J.; Tooney, P.A.; Scott, R.J.; Carr, V.J.; Cairns, M.J. Transcriptome Sequencing Revealed Significant Alteration of Cortical Promoter Usage and Splicing in Schizophrenia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, B.; Sanderson, C.M. A Protein Interaction Framework for Human mRNA Degradation. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Estévez, A.M.; Lehner, B.; Sanderson, C.M.; Ruppert, T.; Clayton, C. The Roles of Intersubunit Interactions in Exosome Stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 34943–34951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burns, D.T.; Donkervoort, S.; Müller, J.S.; Knierim, E.; Bharucha-Goebel, D.; Faqeih, E.A.; Bell, S.K.; AlFaifi, A.Y.; Monies, D.; Millan, F.; et al. Variants in EXOSC9 Disrupt the RNA Exosome and Result in Cerebellar Atrophy with Spinal Motor Neuronopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robay, D.; Patel, H.; Simpson, M.A.; Brown, N.A.; Crosby, A.H. Endogenous spartin, mutated in hereditary spastic paraplegia, has a complex subcellular localization suggesting diverse roles in neurons. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 2764–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Miao, H.; Yang, H.; Gong, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H.; Pan, H. Dwarfism in Troyer syndrome: A family with SPG20 compound heterozygous mutations and a literature review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1462, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 (Twin of Patient 6) | Patient 6 (Twin of Patient 5) | Patient 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | F | F | F | F | F | M |

| Age (years/months) at first examination | 4 years | 3 years and 11 months | 5 months | 9 months | 6 months | 6 months | 8 months |

| Auxological parameters at birth (OFC, weight, length) | Weight 1.50 kg (50°–75° percentile); length 46 cm (>90° percentile) | n.a. | OFC 38 cm (95° percentile); weight 4.0 kg (85°–97° percentile); length 52 cm (85°–97° percentile) | Weight 2.25 kg(<5° percentile); length 47 cm (15° percentile) | OFC 31.5 cm (10°–25° percentile); weight 2.04 kg (<1° percentile); length 42 cm (<1° percentile) | Weight 1.95 kg (<1° percentile); length 42 cm (<1° percentile) | OFC 32.9 cm (50° percentile); weight 2.075 kg (10° percentile); length 45 cm (>25° percentile) |

| Auxological parameters at evaluation (OFC, weight, length) | OFC 49.5 cm (25°–50° percentile); weight 17 kg (50°–75° percentile); height 101 cm (25–50° percentile) | OFC 51 cm (25°–50° percentile); weight 17 kg (50°–75°percentile); height 103 cm (25°–50° percentile) | OFC 51 cm (>99° percentile); weight 11.5 kg (25° percentile) | OFC 38.8 cm (<5° percentile); weight 6.63 kg (75°–90° percentile); height 63 cm (<5° percentile) | OFC 39.8 cm (3°–10° percentile); weight 5. 16 kg (<5° percentile); height 62 cm (25° percentile) | OFC 40 cm (3–10° percentile) | Weight 5.8 kg (25° percentile); height 60 cm (50° percentile) |

| RB characteristics (age at diagnosis, tumor) | 5 months; unilateral, left eye | 3 years old; bilateral | 4 months; unilateral, left eye | 9 months; unilateral, right eye | 6 months; unilateral, left eye | 6 months; unilateral, left eye | 7 months; bilateral |

| RB treatment | Chemotherapy and laser therapy; enucleation | Enucleation of the right eye; chemotherapy of the left eye | Enucleation | Chemotherapy | Systemic and intra- arterial chemotherapy | Brachytherapy | Chemotherapy |

| Facial dysmorphisms (yes/no) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Developmental psychomotor delay (yes/no) | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Follow up (age in years; considerations) | 14 years and 9 months; good school performance, no specific facial features, denied further major diseases. No ID or developmental delay. | 12 years; no developmental delay, very good school performance, good social integration, normal performance in sports. | 3 years; independent walking, acquired fine motor skills. Good language skills. | 1 year and 3 months: neuromotor delay. Acquired sitting position, hands folded but fine motor skills. Absent babble speech, no crawling or walking, but supine to prone rolling. | 7 years; important psychomotor delay. No language skills, not acquired sphincter control. Walking only with support. Important hand stereotypies on the midline, trunk movements. 13 years: no language skills, nor independent walking. No hands stereotypes anymore; normal sexual development. | 7 years; important psychomotor delay. No language skills, not acquired sphincter control, walking only with support. Important hand stereotypies on the midline, trunk movements. Important difficulties in walking. 13 years: no language skills, nor independent walking. No hands stereotypes anymore; normal sexual development. | 2 years; axial hypotonia, poor head control. No sitting position, absent language. Exclusively liquid feeding. |

| Dysmorphic Features | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 (Twin of Patient 6) | Patient 6 (Twin of Patient 5) | Patient 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad and wide forehead | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Frontal bossing | − | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Bushy eyebrows | − | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| Deeply-set or small eyes | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Nostrils anomalies | − | +; hypoplastic | +; everted | − | − | − | − |

| Prominent philtrum | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Depressed nasal root | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Broad nasal bridge | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Thick everted lower lip | − | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Ear abnormalities | − | +; overfolded helix | − | +; low-set posteriorly rotated ears | − | − | +; low-set |

| Others | |||||||

| Hypertrichosis | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Micrognathia | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Altered head morphology | − | − | − | − | Brachycephaly | Brachycephaly | Plagiocephaly |

| Clinodactyly | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Cutis Marmorata | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Brain anomalies | Frontal capillary angioma | − | − | − | Agenesis of the corpus callosum | − | Brain stem hypoplasia |

| Cardiac anomalies | − | − | − | − | 3 mm interatrial defect, with left > right shunt and slight dilation of right chambers | − | − |

| Hearing loss | − | − | − | − | − | − | +; sensorineural, bilateral |

| Features | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 (Twin of Patient 6) | Patient 6 (Twin of Patient 5) | Patient 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of deletion/heredity | de novo | n.a. | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo |

| Array CGH analysis (proximal-distal breakpoints of the deletion) | 42532854_50275341 | 46851293_49614283 | 45712553_71933242 | 30898736_49309890 | 35876405_69983996 | 35876405_69983996 | 35398085_75462802 |

| Location and size of deletion | 13q14.11q14.2; 7.8 Mb | 13q14.14q14.2; 2.76 Mb | 13q14.12q21.33; 26.24 Mb | 13q12.3q14.2; 18.4 Mb | 13q13.2q21.33; 34.1 Mb | 13q13.2q21.33; 34.1 Mb | 13q13.2q22.3; 40 Mb |

| Gene Symbol (OMIM#). | Phenotype (OMIM#) | Inheritance | Association with Neurodevelopmental Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBEA (OMIM#604889) | Neurodevelopmental disorder with or without early-onset generalized epilepsy (OMIM#619157) | AD | Reported mutated in autosomal dominant neurodevelopmental disorder with or without epilepsy [12]. It was cited with a score of 1 in the SFARI Gene database as a candidate gene for autism spectrum disorder [13]. It is involved in synaptic transmission and exocytosis [14], neuron excitability, and brain development [15]. |

| MAB21L1 (OMIM#601280) | Cerebellar, ocular, craniofacial, and genital syndrome (OMIM#618479) | AR | Loss-of-function mutations cause an extremely rare autosomal recessive condition, the Cerebellar, ocular, craniofacial, and genital (COFG) syndrome, characterized by moderate to severe developmental delay and impaired intellectual development [16]. |

| DCLK1 (OMIM#604742) | Association with neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders | N/A | The gene exerts multiple roles in neurogenesis, neuronal migration, axon/dendrite growth, and spine formation [17,18,19,20]. GWAS indicated an association between DCLK1 and neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders [21]. |

| EXOSC8 (OMIM#606019) | Pontocerebellar hypoplasia, type 1C (OMIM#616081) | AR | Patients with recessive EXOSC8 mutations present with a characteristic spectrum of overlapping phenotypes of infantile onset hypomyelination, cerebellar and corpus callosum hypoplasia and spinal muscular atrophy [22,23]. |

| SPART (OMIM#607111) | Troyer syndrome (OMIM#275900) | AR | Causative gene of the Troyer Syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by spastic paraparesis, developmental delay, dysarthria, distal amyotrophy, skeletal defects, and short stature [24,25]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Privitera, F.; Calonaci, A.; Doddato, G.; Papa, F.T.; Baldassarri, M.; Pinto, A.M.; Mari, F.; Longo, I.; Caini, M.; Galimberti, D.; et al. 13q Deletion Syndrome Involving RB1: Characterization of a New Minimal Critical Region for Psychomotor Delay. Genes 2021, 12, 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12091318

Privitera F, Calonaci A, Doddato G, Papa FT, Baldassarri M, Pinto AM, Mari F, Longo I, Caini M, Galimberti D, et al. 13q Deletion Syndrome Involving RB1: Characterization of a New Minimal Critical Region for Psychomotor Delay. Genes. 2021; 12(9):1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12091318

Chicago/Turabian StylePrivitera, Flavia, Arianna Calonaci, Gabriella Doddato, Filomena Tiziana Papa, Margherita Baldassarri, Anna Maria Pinto, Francesca Mari, Ilaria Longo, Mauro Caini, Daniela Galimberti, and et al. 2021. "13q Deletion Syndrome Involving RB1: Characterization of a New Minimal Critical Region for Psychomotor Delay" Genes 12, no. 9: 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12091318

APA StylePrivitera, F., Calonaci, A., Doddato, G., Papa, F. T., Baldassarri, M., Pinto, A. M., Mari, F., Longo, I., Caini, M., Galimberti, D., Hadjistilianou, T., De Francesco, S., Renieri, A., & Ariani, F. (2021). 13q Deletion Syndrome Involving RB1: Characterization of a New Minimal Critical Region for Psychomotor Delay. Genes, 12(9), 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12091318