FMR1 and Autism, an Intriguing Connection Revisited

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fragile X Syndrome

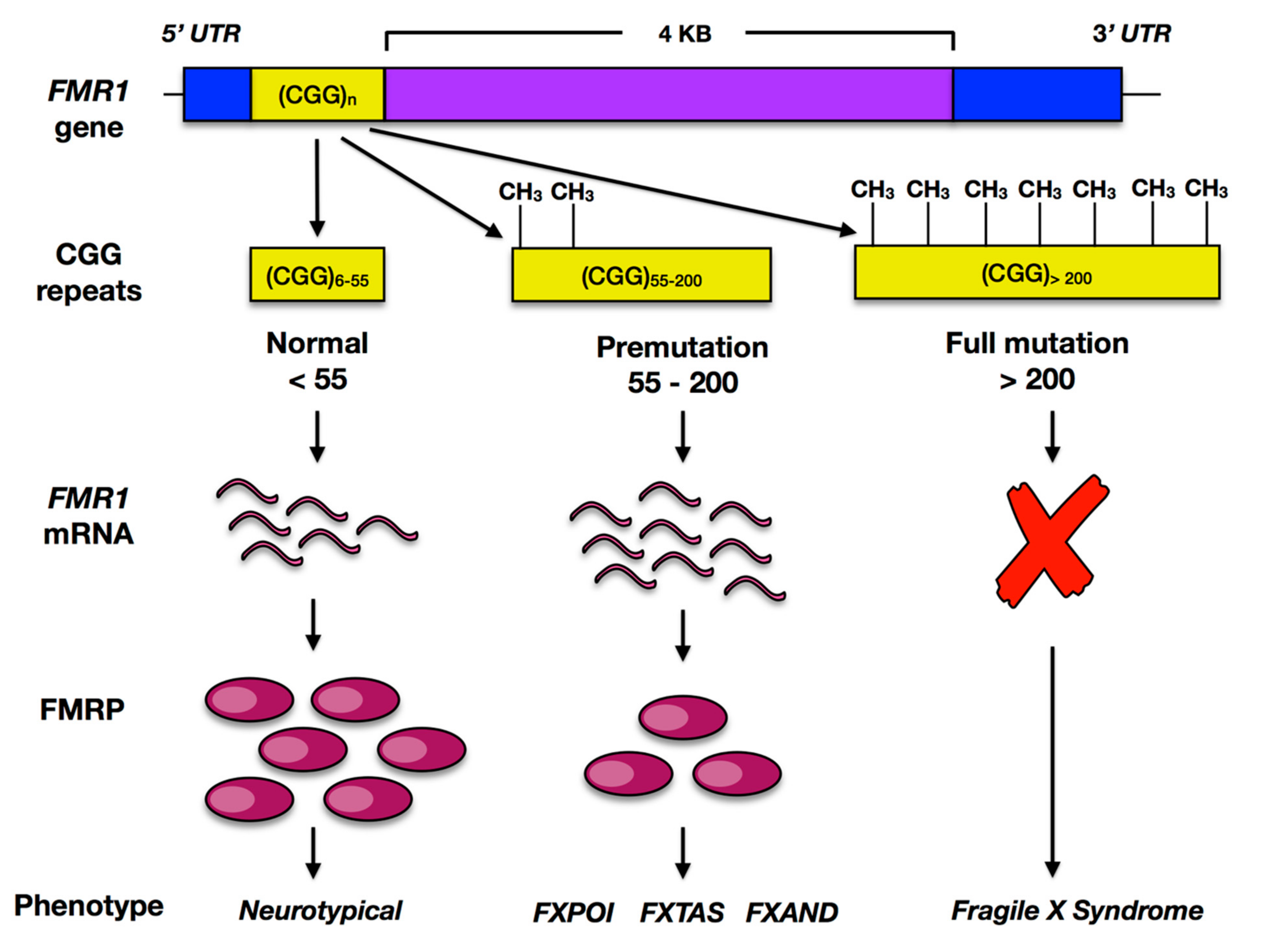

2.1. FMR1

2.2. FMRP

3. FMR1 and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Synaptic Dysfunction

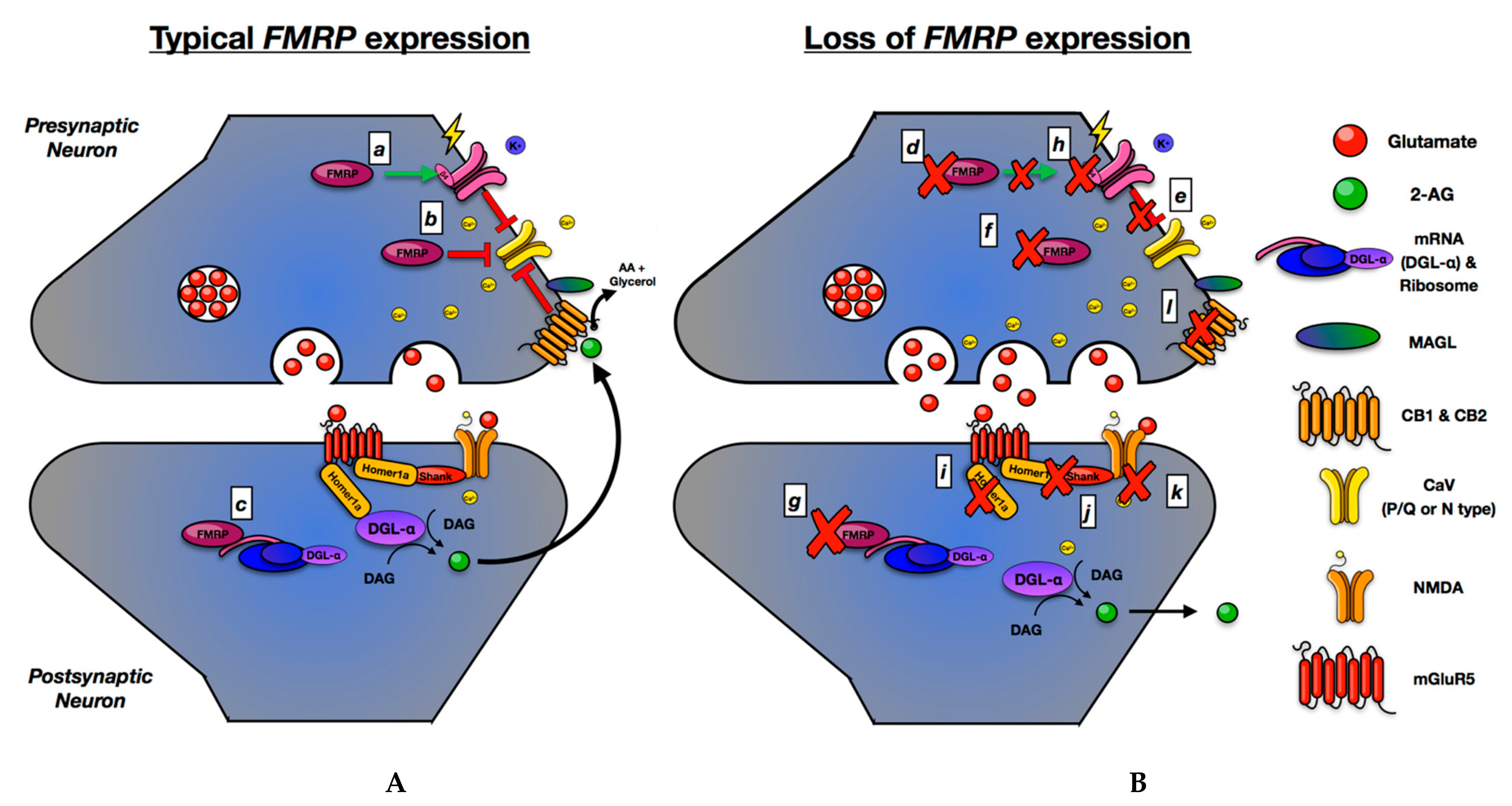

4. The Presynaptic Hypothesis of FMR1 and ASD

Overview

5. ECS

5.1. ECS, FMR1, and ASD—Clinical Correlates

5.2. ECS, FMRP, and ASD—Preclinical Studies

5.3. ECS and ASD—Potential Therapeutics

6. Large Conductance Voltage and Ca2+ Sensitive K+ (BKCa) Channels

6.1. BKCa, FMR1, and ASD—Clinical Correlates

6.2. BKCa, FMR1, and ASD—Preclinical Studies

6.3. BKCa, FMR1, and ASD—Therapeutics

7. CaV2.2

CaV2.2 and ASD—Clinical Correlates

8. Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Baio, J.; Washington, A.; Patrick, M.; DiRienzo, M.; Christensen, D.L.; Wiggins, L.D.; Pettygrove, S.; Andrews, J.G.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2020, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt, E.; Gillberg, C.; Gillberg, C. Autism after adolescence: Population-based 13-to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2005, 35, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilger, J.W.; Kaplan, B.J. Atypical brain development: A conceptual framework for understanding developmental learning disabilities. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2001, 20, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.-C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Baron-Cohen, S. Autism. Lancet 2014, 383, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tick, B.; Bolton, P.; Happe, F.; Rutter, M.; Rijsdijk, F. Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of twin studies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallmayer, J.; Cleveland, S.; Torres, A.; Phillips, J.; Cohen, B.; Torigoe, T.; Miller, J.; Fedele, A.; Collins, J.; Smith, K. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velinov, M. Genomic Copy Number Variations in the Autism Clinic—Work in Progress. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitar, T.; Hleihel, W.; Marouillat, S.; Vonwill, S.; Vuillaume, M.L.; Soufia, M.; Vourc’h, P.; Laumonnier, F.; Andres, C.R. Identification of rare copy number variations reveals PJA2, APCS, SYNPO, and TAC1 as novel candidate genes in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2019, 7, e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebat, J.; Lakshmi, B.; Malhotra, D.; Troge, J.; Lese-Martin, C.; Walsh, T.; Yamrom, B.; Yoon, S.; Krasnitz, A.; Kendall, J. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science 2007, 316, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterstrom, F.K.; Kosmicki, J.A.; Wang, J.; Breen, M.S.; De Rubeis, S.; An, J.Y.; Peng, M.; Collins, R.; Grove, J.; Klei, L.; et al. Large-Scale Exome Sequencing Study Implicates Both Developmental and Functional Changes in the Neurobiology of Autism. Cell 2020, 180, 568–584.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, B.S.; Geschwind, D.H. Advances in autism genetics: On the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State, M.W.; Levitt, P. The conundrums of understanding genetic risks for autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strömland, K.; Nordin, V.; Miller, M.; Akerström, B.; Gillberg, C. Autism in thalidomide embryopathy: A population study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1994, 36, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanson, J.L.; Bolaria, R.; Snyder, R.E.; Morse, B.A.; Weiner, L. Physician awareness of fetal alcohol syndrome: A survey of pediatricians and general practitioners. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1995, 152, 1071. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.; Gronborg, T.K.; Sorensen, M.J.; Schendel, D.; Parner, E.T.; Pedersen, L.H.; Vestergaard, M. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA 2013, 309, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, S.; Rutter, M. Infantile autism: A genetic study of 21 twin pairs. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1977, 18, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilissen, C.; Hehir-Kwa, J.Y.; Thung, D.T.; van de Vorst, M.; van Bon, B.W.; Willemsen, M.H.; Kwint, M.; Janssen, I.M.; Hoischen, A.; Schenck, A.; et al. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature 2014, 511, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rubeis, S.; Buxbaum, J.D. Genetics and genomics of autism spectrum disorder: Embracing complexity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, R24–R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossifov, I.; O’Roak, B.J.; Sanders, S.J.; Ronemus, M.; Krumm, N.; Levy, D.; Stessman, H.A.; Witherspoon, K.T.; Vives, L.; Patterson, K.E.; et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature 2014, 515, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, M.; Sur, M. Genes, circuits, and precision therapies for autism and related neurodevelopmental disorders. Science 2015, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S.B.; Allanson, J.E. Management of Genetic Syndromes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rylaarsdam, L.; Guemez-Gamboa, A. Genetic Causes and Modifiers of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcedo-Arellano, M.J.; Dufour, B.; McLennan, Y.; Martinez-Cerdeno, V.; Hagerman, R. Fragile X syndrome and associated disorders: Clinical aspects and pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 136, 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faundez, V.; Wynne, M.; Crocker, A.; Tarquinio, D. Molecular Systems Biology of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Rett Syndrome as an Archetype. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardet, M.; Crusio, W.E. Fmr1 KO mice as a possible model of autistic features. Sci. World J. 2006, 6, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelsohn, N.J.; Schaefer, G.B. Genetic evaluation of autism. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2008, 15, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, G.B.; Mendelsohn, N.J. Genetics evaluation for the etiologic diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Gen. Med. 2008, 10, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, W.E.; Kidd, S.A.; Andrews, H.F.; Budimirovic, D.B.; Esler, A.; Haas-Givler, B.; Stackhouse, T.; Riley, C.; Peacock, G.; Sherman, S.L.; et al. Autism spectrum disorder in fragile X syndrome: Cooccurring conditions and current treatment. Pediatrics 2017, 139, S194–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talisa, V.B.; Boyle, L.; Crafa, D.; Kaufmann, W.E. Autism and anxiety in males with fragile X syndrome: An exploratory analysis of neurobehavioral profiles from a parent survey. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2014, 164A, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomquist, H.K.S.; Bohman, M.; Edvinsson, S.O.; Gillberg, C.; Gustavson, K.H.; Holmgren, G.; Wahlström, J. Frequency of the fragile X syndrome in infantile autism. Clin. Genet. 1985, 27, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Youings, S.; Dennis, N.; Latsky, L.; Linehan, P.; McKechnie, N.; Macpherson, J.; Pound, M.; Jacobs, P. Population screening at the FRAXA and FRAXE loci: Molecular analyses of boys with learning difficulties and their mothers. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996, 5, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.C.; Meadows, K.L.; Newman, J.L.; Taft, L.F.; Scott, E.; Leslie, M.; Shubek, L.; Holmgreen, P.; Yeargin-Allsopp, M.; Boyle, C. Prevalence of the fragile X syndrome in African-Americans. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 110, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.R.; Kronengold, J.; Gazula, V.R.; Chen, Y.; Strumbos, J.G.; Sigworth, F.J.; Navaratnam, D.; Kaczmarek, L.K. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls gating of the sodium-activated potassium channel Slack. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.Y.; Rotman, Z.; Blundon, J.A.; Cho, Y.; Cui, J.; Cavalli, V.; Zakharenko, S.S.; Klyachko, V.A. FMRP regulates neurotransmitter release and synaptic information transmission by modulating action potential duration via BK channels. Neuron 2013, 77, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferron, L.; Nieto-Rostro, M.; Cassidy, J.S.; Dolphin, A.C. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls synaptic vesicle exocytosis by modulating N-type calcium channel density. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, V.; Jin, P.; Ceman, S.; Darnell, J.C.; O’Donnell, W.T.; Tenenbaum, S.A.; Jin, X.; Feng, Y.; Wilkinson, K.D.; Keene, J.D.; et al. Microarray identification of FMRP-associated brain mRNAs and altered mRNA translational profiles in fragile X syndrome. Cell 2001, 107, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.; Jacobs, P.; Morton, N.; Froster-Iskenius, U.; Howard-Peebles, P.; Nielsen, K.; Partington, M.; Sutherland, G.; Turner, G.; Watson, M. Further segregation analysis of the fragile X syndrome with special reference to transmitting males. Hum. Genet. 1985, 69, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkerk, A.J.; Pieretti, M.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Fu, Y.-H.; Kuhl, D.P.; Pizzuti, A.; Reiner, O.; Richards, S.; Victoria, M.F.; Zhang, F.; et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 1991, 65, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolin, S.L.; Brown, W.T.; Glicksman, A.; Houck Jr, G.E.; Gargano, A.D.; Sullivan, A.; Biancalana, V.; Bröndum-Nielsen, K.; Hjalgrim, H.; Holinski-Feder, E. Expansion of the fragile X CGG repeat in females with premutation or intermediate alleles. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomay, K.L.; Lee, C.H.; Bruno, J.L.; Lightbody, A.A.; Reiss, A.L. Closing the gender gap in fragile X syndrome: Review of females with fragile X syndrome and preliminary research findings. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, D.K.; Zhang, F.; Ashley Jr, C.T.; Warren, S.T. The ChickenFMR1Gene Is Highly Conserved with a CCT 5′-Untranslated Repeat and Encodes an RNA-Binding Protein. Genomics 1996, 31, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bassell, G.J.; Warren, S.T. Fragile X syndrome: Loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron 2008, 60, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrick, L.K.; Hashimoto, H.; Cheng, X.; Warren, S.T. Human FMRP contains an integral tandem Agenet (Tudor) and KH motif in the amino terminal domain. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhart, D.E.; Malter, H.E.; Feng, Y.; Warren, S.T. The fragile X mental retardation protein is a ribonucleoprotein containing both nuclear localization and nuclear export signals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996, 5, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackett, D.M.; Qing, F.; Amieux, P.S.; Sellers, D.L.; Horner, P.J.; Morris, D.R. FMR1 transcript isoforms: Association with polyribosomes; regional and developmental expression in mouse brain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorio, D.A.; Jackson, C.M.; Liu, Y.; Rubel, E.W.; Wang, Y. Cellular distribution of the fragile X mental retardation protein in the mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 818–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, J.; Gholizadeh, S.; Niibori, Y.; Pacey, L.K.; Halder, S.K.; Koxhioni, E.; Konno, A.; Hirai, H.; Hampson, D.R. FMRP Expression Levels in Mouse Central Nervous System Neurons Determine Behavioral Phenotype. Hum. Gene. Ther. 2016, 27, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, S.; Halder, S.K.; Hampson, D.R. Expression of fragile X mental retardation protein in neurons and glia of the developing and adult mouse brain. Brain Res. 2015, 1596, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, K.A.; Dominick, K.C.; Erickson, C.A. Developmental studies in fragile X syndrome. J. Neurodevelop. Dis. 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antar, L.N.; Afroz, R.; Dictenberg, J.B.; Carroll, R.C.; Bassell, G.J. Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation regulates fragile x mental retardation protein and FMR1 mRNA localization differentially in dendrites and at synapses. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 2648–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akins, M.R.; Berk-Rauch, H.E.; Kwan, K.Y.; Mitchell, M.E.; Shepard, K.A.; Korsak, L.I.; Stackpole, E.E.; Warner-Schmidt, J.L.; Sestan, N.; Cameron, H.A. Axonal ribosomes and mRNAs associate with fragile X granules in adult rodent and human brains. Hum. Molec. Genet. 2017, 26, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsak, L.I.T.; Mitchell, M.E.; Shepard, K.A.; Akins, M.R. Regulation of neuronal gene expression by local axonal translation. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comery, T.A.; Harris, J.B.; Willems, P.J.; Oostra, B.A.; Irwin, S.A.; Weiler, I.J.; Greenough, W.T. Abnormal dendritic spines in fragile X knockout mice: Maturation and pruning deficits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 5401–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Martin, A.; Crespo, M.; Portera-Cailliau, C. Delayed stabilization of dendritic spines in fragile X mice. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 7793–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.X.; Portera-Cailliau, C. The trouble with spines in fragile X syndrome: Density, maturity and plasticity. Neuroscience 2013, 251, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutt, J.; Falley, K.; Richter, D.; Kreienkamp, H.J.; Kindler, S. Fragile X mental retardation protein regulates the levels of scaffold proteins and glutamate receptors in postsynaptic densities. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 25479–25487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, C.T.; Wilkinson, K.D.; Reines, D.; Warren, S.T. FMR1 protein: Conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science 1993, 262, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Dreyfuss, G. The protein product of the fragile X gene, FMR1, has characteristics of an RNA-binding protein. Cell 1993, 74, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, C.; Bardoni, B.; Mandel, J.L.; Ehresmann, B.; Ehresmann, C.; Moine, H. The fragile X mental retardation protein binds specifically to its mRNA via a purine quartet motif. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 4803–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siomi, H.; Choi, M.; Siomi, M.C.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Dreyfuss, G. Essential role for KH domains in RNA binding: Impaired RNA binding by a mutation in the KH domain of FMR1 that causes fragile X syndrome. Cell 1994, 77, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Hollingworth, D.; Adinolfi, S.; Castets, M.; Kelly, G.; Frenkiel, T.A.; Bardoni, B.; Pastore, A. The structure of the N-terminal domain of the fragile X mental retardation protein: A platform for protein-protein interaction. Structure 2006, 14, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Brown, M.R.; Hyland, C.; Chen, Y.; Kronengold, J.; Fleming, M.R.; Kohn, A.B.; Moroz, L.L.; Kaczmarek, L.K. Regulation of neuronal excitability by interaction of fragile X mental retardation protein with slack potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 15318–15327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bonnan, A.; Bony, G.; Ferezou, I.; Pietropaolo, S.; Ginger, M.; Sans, N.; Rossier, J.; Oostra, B.; LeMasson, G.; et al. Dendritic channelopathies contribute to neocortical and sensory hyperexcitability in Fmr1(-/y) mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, L.; Novazzi, C.G.; Pilch, K.S.; Moreno, C.; Ramgoolam, K.; Dolphin, A.C. FMRP regulates presynaptic localization of neuronal voltage gated calcium channels. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 138, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagnola, S.; Delhaye, S.; Folci, A.; Paquet, A.; Brau, F.; Duprat, F.; Jarjat, M.; Grossi, M.; Beal, M.; Martin, S.; et al. New Insights Into the Role of Cav2 Protein Family in Calcium Flux Deregulation in Fmr1-KO Neurons. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yun, S.; Seto, J.; Liu, W.; Toth, M. The fragile X mental retardation protein binds and regulates a novel class of mRNAs containing U rich target sequences. Neuroscience 2003, 120, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, B.E.; Johnston, D.; Brager, D.H. Cell-Type Specific Channelopathies in the Prefrontal Cortex of the fmr1-/y Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. eNeuro 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brager, D.H.; Akhavan, A.R.; Johnston, D. Impaired dendritic expression and plasticity of h-channels in the fmr1−/y mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Cell Rep. 2012, 1, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagni, C.; Zukin, R.S. A Synaptic Perspective of Fragile X Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron 2019, 101, 1070–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudouin, S.J.; Gaudias, J.; Gerharz, S.; Hatstatt, L.; Zhou, K.; Punnakkal, P.; Tanaka, K.F.; Spooren, W.; Hen, R.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Shared synaptic pathophysiology in syndromic and nonsyndromic rodent models of autism. Science 2012, 338, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakar, A.L.; Dolen, G.; Bear, M.F. The pathophysiology of fragile X (and what it teaches us about synapses). Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 417–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, S.; Fu, Y.; Li, X. Synaptic proteins and receptors defects in autism spectrum disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Norris, R.H.; Gordon, S.L.; Nithianantharajah, J. Neurodevelopmental synaptopathies: Insights from behaviour in rodent models of synapse gene mutations. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, B.D.; Osterweil, E.K.; Bear, M.F. Mutations causing syndromic autism define an axis of synaptic pathophysiology. Nature 2011, 480, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, M.F.; Huber, K.M.; Warren, S.T. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004, 27, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Sugihara, H.; Nawa, H.; Shigemoto, R.; Mizuno, N.; Nakanishi, S. Molecular characterization of a novel metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 coupled to inositol phosphate/Ca2+ signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 13361–13368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, K.M.; Gallagher, S.M.; Warren, S.T.; Bear, M.F. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7746–7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Folsom, T.D.; Kneeland, R.E.; Liesch, S.B. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 upregulation in children with autism is associated with underexpression of both Fragile X mental retardation protein and GABAA receptor beta 3 in adults with autism. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2011, 294, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Folsom, T.D. GABA receptor subunit distribution and FMRP-mGluR5 signaling abnormalities in the cerebellum of subjects with schizophrenia, mood disorders, and autism. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 167, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, R.J., 3rd; Geigenmuller, U.; Hovhannisyan, H.; Trautman, E.; Pinard, R.; Rathmell, B.; Carpenter, R.; Margulies, D. High-throughput sequencing of mGluR signaling pathway genes reveals enrichment of rare variants in autism. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Foldy, C.; Malenka, R.C.; Sudhof, T.C. Autism-associated neuroligin-3 mutations commonly disrupt tonic endocannabinoid signaling. Neuron 2013, 78, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledziowska, M.; Galloway, J.; Baudouin, S.J. Evidence for a Contribution of the Nlgn3/Cyfip1/Fmr1 Pathway in the Pathophysiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuroscience 2019, 445, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Molinaro, G.; Collins, K.A.; Hays, S.A.; Paylor, R.; Worley, P.F.; Szumlinski, K.K.; Huber, K.M. Selective Disruption of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5-Homer Interactions Mimics Phenotypes of Fragile X Syndrome in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 2131–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.M.; Sepers, M.; Henstridge, C.M.; Lassalle, O.; Neuhofer, D.; Martin, H.; Ginger, M.; Frick, A.; DiPatrizio, N.V.; Mackie, K.; et al. Uncoupling of the endocannabinoid signalling complex in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloisi, E.; Le Corf, K.; Dupuis, J.; Zhang, P.; Ginger, M.; Labrousse, V.; Spatuzza, M.; Georg Haberl, M.; Costa, L.; Shigemoto, R.; et al. Altered surface mGluR5 dynamics provoke synaptic NMDAR dysfunction and cognitive defects in Fmr1 knockout mice. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.H.; Alger, B.E. Homer protein-metabotropic glutamate receptor binding regulates endocannabinoid signaling and affects hyperexcitability in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 3938–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Bozdagi, O.; Scattoni, M.L.; Wohr, M.; Roullet, F.I.; Katz, A.M.; Abrams, D.N.; Kalikhman, D.; Simon, H.; Woldeyohannes, L.; et al. Reduced excitatory neurotransmission and mild autism-relevant phenotypes in adolescent Shank3 null mutant mice. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6525–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, D.D.; Brose, N. Evidence for a common endocannabinoid-related pathomechanism in autism spectrum disorders. Neuron 2013, 78, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skafidas, E.; Testa, R.; Zantomio, D.; Chana, G.; Everall, I.P.; Pantelis, C. Predicting the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder using gene pathway analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamain, S.; Quach, H.; Betancur, C.; Rastam, M.; Colineaux, C.; Gillberg, I.C.; Soderstrom, H.; Giros, B.; Leboyer, M.; Gillberg, C.; et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, C.M.; Betancur, C.; Boeckers, T.M.; Bockmann, J.; Chaste, P.; Fauchereau, F.; Nygren, G.; Rastam, M.; Gillberg, I.C.; Anckarsater, H.; et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Delaby, E.; Merico, D.; Barbosa, M.; Merikangas, A.; Klei, L.; Thiruvahindrapuram, B.; Xu, X.; Ziman, R.; Wang, Z.; et al. Convergence of genes and cellular pathways dysregulated in autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 94, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, A.P.; Gokhale, A.; Moreno-De-Luca, A.; Sanyal, S.; Waddington, J.L.; Faundez, V. Neurodevelopmental disorders: Mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, M.; Jagannathan, K.; Calhoun, V.D.; Miller, L.; Stevens, M.C.; Sahl, R.; O’Boyle, J.G.; Schultz, R.T.; Pearlson, G.D. Abnormal functional connectivity of default mode sub-networks in autism spectrum disorder patients. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, G.J.; Hepburn, S.; Rojas, D.C. Structural Covariance of Sensory Networks, the Cerebellum, and Amygdala in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, M.A.; Keller, T.A.; Malave, V.L.; Kana, R.K.; Varma, S. Autism as a neural systems disorder: A theory of frontal-posterior underconnectivity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1292–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twitchell, W.; Brown, S.; Mackie, K. Cannabinoids inhibit N- and P/Q-type calcium channels in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1997, 78, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, B.; Pietropaolo, S.; Meme, S.; Laudier, B.; Laugeray, A.; Doisne, N.; Quartier, A.; Lefeuvre, S.; Got, L.; Cahard, D.; et al. Rescue of fragile X syndrome phenotypes in Fmr1 KO mice by a BKCa channel opener molecule. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laumonnier, F.; Roger, S.; Guérin, P.; Molinari, F.; M’rad, R.; Cahard, D.; Belhadj, A.; Halayem, M.; Persico, A.M.; Elia, M. Association of a functional deficit of the BK Ca channel, a synaptic regulator of neuronal excitability, with autism and mental retardation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, M.; Rossi, S.; Bari, M.; De Chiara, V.; Rapino, C.; Musella, A.; Bernardi, G.; Bagni, C.; Centonze, D. Abnormal mGlu 5 receptor/endocannabinoid coupling in mice lacking FMRP and BC1 RNA. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 1500–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straiker, A.; Min, K.T.; Mackie, K. Fmr1 deletion enhances and ultimately desensitizes CB(1) signaling in autaptic hippocampal neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 56, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, J.C.; Van Driesche, S.J.; Zhang, C.; Hung, K.Y.S.; Mele, A.; Fraser, C.E.; Stone, E.F.; Chen, C.; Fak, J.J.; Chi, S.W. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell 2011, 146, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferron, L. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls ion channel expression and activity. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 5861–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Alger, B.E. Enhanced endocannabinoid signaling elevates neuronal excitability in fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 5724–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Bey, A.L.; Katz, B.M.; Badea, A.; Kim, N.; David, L.K.; Duffney, L.J.; Kumar, S.; Mague, S.D.; Hulbert, S.W.; et al. Altered mGluR5-Homer scaffolds and corticostriatal connectivity in a Shank3 complete knockout model of autism. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; McCoy, P.A.; Rodriguiz, R.M.; Pan, Y.; Je, H.S.; Roberts, A.C.; Kim, C.J.; Berrios, J.; Colvin, J.S.; Bousquet-Moore, D.; et al. Synaptic dysfunction and abnormal behaviors in mice lacking major isoforms of Shank3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 3093–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyke, W.; Alarcon, J.M.; Velinov, M.; Chadman, K.K. Pharmacological inhibition of the primary endocannabinoid producing enzyme, DGL-α, induces autism spectrum disorder-like and co-morbid phenotypes in adult C57BL/J mice. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 1375–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; You, Y.; Yue, W.; Jia, M.; Yu, H.; Lu, T.; Wu, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D. Genetic Evidence for Possible Involvement of the Calcium Channel Gene CACNA1A in Autism Pathogenesis in Chinese Han Population. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzo, E.K.; Perez-Cano, L.; Jung, J.Y.; Wang, L.K.; Kashef-Haghighi, D.; Hartl, C.; Singh, C.; Xu, J.; Hoekstra, J.N.; Leventhal, O.; et al. Inherited and De Novo Genetic Risk for Autism Impacts Shared Networks. Cell 2019, 178, 850–866.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, H.; Miyamae, T.; Hansen, G.; Zambrowicz, B.; Flynn, M.; Pedicord, D.; Blat, Y.; Westphal, R.S.; Zaczek, R.; Lewis, D.A.; et al. Postsynaptic diacylglycerol lipase mediates retrograde endocannabinoid suppression of inhibition in mouse prefrontal cortex. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 4857–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Dinh, D.; Lee, D.; Li, D.; Anguren, A.; Moreno-Sanz, G.; Gall, C.M.; Piomelli, D. Enhancement of Anandamide-Mediated Endocannabinoid Signaling Corrects Autism-Related Social Impairment. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyke, W.; Alarcon, J.M.; Velinov, M.; Chadman, K.K. Pharmacological inhibition of BKCa channels induces a specific social deficit in adult C57BL6/J mice. Behav. Neurosci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, L.A.; Lolait, S.J.; Brownstein, M.J.; Young, A.C.; Bonner, T.I. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 1990, 346, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, S.; Thomas, K.L.; Abu-Shaar, M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 1993, 365, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devane, W.A.; Hanus, L.; Breuer, A.; Pertwee, R.G.; Stevenson, L.A.; Griffin, G.; Gibson, D.; Mandelbaum, A.; Etinger, A.; Mechoulam, R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 1992, 258, 1946–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M.; Ohno-Shosaku, T.; Hashimotodani, Y.; Uchigashima, M.; Watanabe, M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 309–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, E.; Benito, C.; Pazos, M.R.; Barbachano, A.; Fajardo, O.; González, S.; Tolón, R.M.; Romero, J. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors are expressed by perivascular microglial cells in the human brain: An immunohistochemical study. Synapse 2004, 53, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makriyannis, A.; Tian, X.; Guo, J. How lipophilic cannabinergic ligands reach their receptor sites. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2005, 77, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, T.; Kondo, S.; Sukagawa, A.; Nakane, S.; Shinoda, A.; Itoh, K.; Yamashita, A.; Waku, K. 2-Arachidonoylgylcerol: A possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 215, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhara, Y.; Takayama, H.; Nakane, S.; Miyashita, T.; Waku, K.; Sugiura, T. Synthesis and biological activities of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand, and its metabolically stable ether-linked analogues. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, N.; Schweitzer, P.; Piomelli, D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature 1997, 388, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.M.; Mangieri, R.; Stapleton, C.; Kim, J.; Fegley, D.; Wallace, M.; Mackie, K.; Piomelli, D. Stimulation of endocannabinoid formation in brain slice cultures through activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogno, T.; Howell, F.; Williams, G.; Minassi, A.; Cascio, M.G.; Ligresti, A.; Matias, I.; Schiano-Moriello, A.; Paul, P.; Williams, E.J.; et al. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 163, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno-Shosaku, T.; Hashimotodani, Y.; Ano, M.; Takeda, S.; Tsubokawa, H.; Kano, M. Endocannabinoid signalling triggered by NMDA receptor-mediated calcium entry into rat hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 2007, 584, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Bisogno, T.; Di Marzo, V.; Alger, B.E. Endocannabinoids generated by Ca2+ or by metabotropic glutamate receptors appear to arise from different pools of diacylglycerol lipase. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenowitz, S.D.; Regehr, W.G. Calcium dependence of retrograde inhibition by endocannabinoids at synapses onto Purkinje cells. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 6373–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.; Carpenter, D.; Leslie, F.; Freund, T.; Katona, I.; Sensi, S.; Kathuria, S.; Piomelli, D. Brain monoglyceride lipase participating in endocannabinoid inactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10819–10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulyas, A.I.; Cravatt, B.F.; Bracey, M.H.; Dinh, T.P.; Piomelli, D.; Boscia, F.; Freund, T.F. Segregation of two endocannabinoid-hydrolyzing enzymes into pre- and postsynaptic compartments in the rat hippocampus, cerebellum and amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 20, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Oka, S.; Waku, K. Biosynthesis and degradation of anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol and their possible physiological significance. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids (PLEFA) 2002, 66, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, C.C.; Briley, E.M.; Axelrod, J.; Simpson, J.T.; Mackie, K.; Devane, W.A. Anandamide, an endogenous cannabimimetic eicosanoid, binds to the cloned human cannabinoid receptor and stimulates receptor-mediated signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 7656–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, C.C.; Joyce, K.E.; Briley, E.M.; Mansouri, J.; Mackie, K.; Blond, O.; Lai, Y.; Ma, A.L.; Mitchell, R.L. Comparison of the pharmacology and signal transduction of the human cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995, 48, 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaboula, M.; Poinot-Chazel, C.; Bourrie, B.; Canat, X.; Calandra, B.; Rinaldi-Carmona, M.; Le Fur, G.; Casellas, P. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by stimulation of the central cannabinoid receptor CB1. Biochem. J. 1995, 312, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitler, T.; Alger, B. Postsynaptic spike firing reduces synaptic GABAA responses in hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Neurosci. 1992, 12, 4122–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.I.; Nicoll, R.A. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature 2001, 410, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccarrone, M.; Rossi, S.; Bari, M.; De Chiara, V.; Fezza, F.; Musella, A.; Gasperi, V.; Prosperetti, C.; Bernardi, G.; Finazzi-Agro, A.; et al. Anandamide inhibits metabolism and physiological actions of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauckner, J.E.; Jensen, J.B.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lu, H.-C.; Hille, B.; Mackie, K. GPR55 is a cannabinoid receptor that increases intracellular calcium and inhibits M current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2699–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.D.; Cascio, M.G.; Romano, B.; Duncan, M.; Pertwee, R.G.; Williams, C.M.; Whalley, B.J.; Hill, A.J. Cannabidivarin-rich cannabis extracts are anticonvulsant in mouse and rat via a CB1 receptor-independent mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.; Mercier, M.; Hill, T.; Glyn, S.; Jones, N.; Yamasaki, Y.; Futamura, T.; Duncan, M.; Stott, C.; Stephens, G. Cannabidivarin is anticonvulsant in mouse and rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghuis, P.; Rajnicek, A.M.; Morozov, Y.M.; Ross, R.A.; Mulder, J.; Urban, G.M.; Monory, K.; Marsicano, G.; Matteoli, M.; Canty, A.; et al. Hardwiring the brain: Endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science 2007, 316, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keimpema, E.; Alpar, A.; Howell, F.; Malenczyk, K.; Hobbs, C.; Hurd, Y.L.; Watanabe, M.; Sakimura, K.; Kano, M.; Doherty, P.; et al. Diacylglycerol lipase alpha manipulation reveals developmental roles for intercellular endocannabinoid signaling. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A.; Jeon, O.; Zimmerman, A.; Blue, M.E.; Pevsner, J. Postmortem brain abnormalities of the glutamate neurotransmitter system in autism. Neurology 2001, 57, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalco, D.; Sapone, A.; Giordano, C.; Cirillo, A.; de Magistris, L.; Rossi, F.; Fasano, A.; Bradstreet, J.J.; Maione, S.; Antonucci, N. Cannabinoid receptor type 2, but not type 1, is up-regulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of children affected by autistic disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2686–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.R.; Stanley, C.M.; Foss, T.; Boles, R.G.; McKernan, K. Rare genetic variants in the endocannabinoid system genes CNR1 and DAGLA are associated with neurological phenotypes in humans. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, B.; Baron-Cohen, S. Variation in the human cannabinoid receptor CNR1 gene modulates gaze duration for happy faces. Mol. Autism 2011, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, B.; Kent, L.; Suckling, J.; Bullmore, E.; Baron-Cohen, S. Variations in the human cannabinoid receptor (CNR1) gene modulate striatal responses to happy faces. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 23, 1944–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aran, A.; Eylon, M.; Harel, M.; Polianski, L.; Nemirovski, A.; Tepper, S.; Schnapp, A.; Cassuto, H.; Wattad, N.; Tam, J. Lower circulating endocannabinoid levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhson, D.S.; Krasinska, K.M.; Dallaire, J.A.; Libove, R.A.; Phillips, J.M.; Chien, A.S.; Garner, J.P.; Hardan, A.Y.; Parker, K.J. Plasma anandamide concentrations are lower in children with autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moessner, R.; Marshall, C.R.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Skaug, J.; Pinto, D.; Vincent, J.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Fernandez, B.; Roberts, W.; Szatmari, P.; et al. Contribution of SHANK3 mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartier, A.; Courraud, J.; Thi Ha, T.; McGillivray, G.; Isidor, B.; Rose, K.; Drouot, N.; Savidan, M.A.; Feger, C.; Jagline, H. Novel mutations in NLGN3 causing autism spectrum disorder and cognitive impairment. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 2021–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Roak, B.J.; Vives, L.; Fu, W.; Egertson, J.D.; Stanaway, I.B.; Phelps, I.G.; Carvill, G.; Kumar, A.; Lee, C.; Ankenman, K.; et al. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science 2012, 338, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabeux, J.; Kebir, O.; Gauthier, J.; Hamdan, F.; Xiong, L.; Piton, A.; Spiegelman, D.; Henrion, É.; Millet, B.; Fathalli, F.; et al. Rare mutations in N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2011, 1, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, G.; Hollander, E.; Shepherd, J. The role of ionotropic glutamate receptors in childhood neurodevelopmental disorders: Autism spectrum disorders and fragile x syndrome. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2014, 12, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.-J.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, E. NMDA receptor dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015, 20, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Folsom, T.D. Dysregulation of fragile X mental retardation protein and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in superior frontal cortex of individuals with autism: A postmortem brain study. Mol. Autism 2011, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Folsom, T.D.; Kneeland, R.E.; Yousefi, M.K.; Liesch, S.B.; Thuras, P.D. Impairment of fragile X mental retardation protein-metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 signaling and its downstream cognates ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1, amyloid beta A4 precursor protein, striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase, and homer 1, in autism: A postmortem study in cerebellar vermis and superior frontal cortex. Mol. Autism 2013, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, D.M.; Downey, L.; Conboy, M.; Finn, D.P.; Roche, M. Alterations in the endocannabinoid system in the rat valproic acid model of autism. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 249, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.M.; Astarita, G.; Zhu, C.; Wallace, M.; Mackie, K.; Piomelli, D. A key role for diacylglycerol lipase-alpha in metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent endocannabinoid mobilization. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 72, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronesi, J.A.; Huber, K.M. Homer interactions are necessary for metabotropic glutamate receptor-induced long-term depression and translational activation. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.C.; Xiao, B.; Naisbitt, S.; Yuan, J.P.; Petralia, R.S.; Brakeman, P.; Doan, A.; Aakalu, V.K.; Lanahan, A.A.; Sheng, M.; et al. Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins. Neuron 1999, 23, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cox, B.M.; Jia, Y.; Le, A.A.; Cox, C.D.; Jung, K.M.; Hou, B.; Piomelli, D.; Gall, C.M.; Lynch, G. Treating a novel plasticity defect rescues episodic memory in Fragile X model mice. Mol. Psychiatry 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, M.; Zeidler, Z.; Moulton, K.; Krych, L.; Xia, Z.; Smith, C.B. Endocannabinoid-mediated improvement on a test of aversive memory in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 291, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busquets-Garcia, A.; Maldonado, R.; Ozaita, A. New insights into the molecular pathophysiology of fragile X syndrome and therapeutic perspectives from the animal model. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 53, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis-Gonzalez, M.; Busquets-Garcia, A.; Matute, C.; Maldonado, R.; Mato, S.; Ozaita, A. Possible Therapeutic Doses of Cannabinoid Type 1 Receptor Antagonist Reverses Key Alterations in Fragile X Syndrome Mouse Model. Genes 2016, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonesy, B.C.; Parrish, W.P.; Haddad, H.K.; Stephenson, J.R.; Baldi, R.; Bluett, R.J.; Marks, C.R.; Centanni, S.W.; Folkes, O.M.; Spiess, K.; et al. Role of Striatal Direct Pathway 2-Arachidonoylglycerol Signaling in Sociability and Repetitive Behavior. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonesy, B.C.; Bluett, R.J.; Ramikie, T.S.; Baldi, R.; Hermanson, D.J.; Kingsley, P.J.; Marnett, L.J.; Winder, D.G.; Colbran, R.J.; Patel, S. Genetic disruption of 2-arachidonoylglycerol synthesis reveals a key role for endocannabinoid signaling in anxiety modulation. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenniches, I.; Ternes, S.; Albayram, O.; Otte, D.M.; Bach, K.; Bindila, L.; Michel, K.; Lutz, B.; Bilkei-Gorzo, A.; Zimmer, A. Anxiety, Stress, and Fear Response in Mice With Reduced Endocannabinoid Levels. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 79, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, O.M.; Baldi, R.; Kondev, V.; Marcus, D.J.; Hartley, N.D.; Turner, B.D.; Ayers, J.K.; Baechle, J.J.; Misra, M.P.; Altemus, M.; et al. An endocannabinoid-regulated basolateral amygdala-nucleus accumbens circuit modulates sociability. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1728–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, J.; Aguado, T.; Keimpema, E.; Barabas, K.; Ballester Rosado, C.J.; Nguyen, L.; Monory, K.; Marsicano, G.; Di Marzo, V.; Hurd, Y.L.; et al. Endocannabinoid signaling controls pyramidal cell specification and long-range axon patterning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 8760–8765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, L.; Beverley, J.A.; Steiner, H.; Tseng, K.Y. Differential developmental trajectories for CB1 cannabinoid receptor expression in limbic/associative and sensorimotor cortical areas. Synapse 2011, 65, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudin, M.J.; Hobbs, C.; Doherty, P. DAGL-dependent endocannabinoid signalling: Roles in axonal pathfinding, synaptic plasticity and adult neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 1634–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.E.; Lind, J.; Webster, M.; Weickert, C.S. Developmental trajectory of the endocannabinoid system in human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. BMC Neurosci. 2012, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas Farishta, R.; Robert, C.; Turcot, O.; Thomas, S.; Vanni, M.P.; Bouchard, J.F.; Casanova, C. Impact of CB1 Receptor Deletion on Visual Responses and Organization of Primary Visual Cortex in Adult Mice. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 7697–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hill, M.N.; Hillard, C.J.; McEwen, B.S. Alterations in corticolimbic dendritic morphology and emotional behavior in cannabinoid CB1 receptor-deficient mice parallel the effects of chronic stress. Cereb. Cortex 2011, 21, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keown, C.L.; Datko, M.C.; Chen, C.P.; Maximo, J.O.; Jahedi, A.; Muller, R.A. Network organization is globally atypical in autism: A graph theory study of intrinsic functional connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2017, 2, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keown, C.L.; Shih, P.; Nair, A.; Peterson, N.; Mulvey, M.E.; Muller, R.A. Local functional overconnectivity in posterior brain regions is associated with symptom severity in autism spectrum disorders. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, J.; Bakos, N.; Szirmay, M.; Ledent, C.; Freund, T.F. The effects of genetic and pharmacological blockade of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor on anxiety. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002, 16, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, J.; Varga, B.; Ledent, C.; Barna, I.; Freund, T.F. Context-dependent effects of CB1 cannabinoid gene disruption on anxiety-like and social behaviour in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 19, 1906–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, Y.; Phan, A.; Hill, M.N.; Pfaff, D.W.; McEwen, B.S. CB1 receptor signaling regulates social anxiety and memory. Genes Brain Behav. 2013, 12, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzian, A.L.; Micale, V.; Wotjak, C.T. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 receptors on GABAergic vs. glutamatergic neurons differentially gate sex-dependent social interest in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 40, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Nabbout, R.; Miller, I.; Laux, L.; Zolnowska, M.; Wright, S.; Roberts, C. Long-term cannabidiol treatment in patients with Dravet syndrome: An open-label extension trial. Epilepsia 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Cross, J.H.; Villanueva, V.; Wirrell, E.C.; Privitera, M.; Greenwood, S.M.; Roberts, C.; Checketts, D.; VanLandingham, K.E.; et al. Effect of Cannabidiol on Drop Seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heussler, H.; Cohen, J.; Silove, N.; Tich, N.; Bonn-Miller, M.O.; Du, W.; O’Neill, C.; Sebree, T. A phase 1/2, open-label assessment of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of transdermal cannabidiol (ZYN002) for the treatment of pediatric fragile X syndrome. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2019, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaglia, N.; Bonn-Miller, M.; Hagerman, R. Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome with Cannabidiol: A Case Series Study and Brief Review of the Literature. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2019, 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchel, D.; Stolar, O.; De-Haan, T.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Saban, N.; Fuchs, D.O.; Koren, G.; Berkovitch, M. Oral Cannabidiol Use in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder to Treat Related Symptoms and Co-morbidities. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poleg, S.; Golubchik, P.; Offen, D.; Weizman, A. Cannabidiol as a suggested candidate for treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 89, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, C.M.; Freyberg, J.; Voinescu, B.; Lythgoe, D.; Horder, J.; Mendez, M.A.; Wichers, R.; Ajram, L.; Ivin, G.; Heasman, M.; et al. Effects of cannabidiol on brain excitation and inhibition systems; a randomised placebo-controlled single dose trial during magnetic resonance spectroscopy in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretzsch, C.M.; Voinescu, B.; Mendez, M.A.; Wichers, R.; Ajram, L.; Ivin, G.; Heasman, M.; Williams, S.; Murphy, D.G.; Daly, E.; et al. The effect of cannabidiol (CBD) on low-frequency activity and functional connectivity in the brain of adults with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 33, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Lev Schleider, L.; Mechoulam, R.; Saban, N.; Meiri, G.; Novack, V. Real life Experience of Medical Cannabis Treatment in Autism: Analysis of Safety and Efficacy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamberletti, E.; Gabaglio, M.; Parolaro, D. The Endocannabinoid System and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Insights from Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, C.M.; Voinescu, B.; Lythgoe, D.; Horder, J.; Mendez, M.A.; Wichers, R.; Ajram, L.; Ivin, G.; Heasman, M.; Edden, R.A.E.; et al. Effects of cannabidivarin (CBDV) on brain excitation and inhibition systems in adults with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A single dose trial during magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigli, D.; Cosentino, L.; Raggi, C.; Laviola, G.; Woolley-Roberts, M.; De Filippis, B. Chronic treatment with the phytocannabinoid Cannabidivarin (CBDV) rescues behavioural alterations and brain atrophy in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 140, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamberletti, E.; Gabaglio, M.; Woolley-Roberts, M.; Bingham, S.; Rubino, T.; Parolaro, D. Cannabidivarin Treatment Ameliorates Autism-Like Behaviors and Restores Hippocampal Endocannabinoid System and Glia Alterations Induced by Prenatal Valproic Acid Exposure in Rats. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, P.; Hurst, D.P.; Reggio, P.H. Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids: A Complex Picture. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2017, 103, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannotti, F.A.; Hill, C.L.; Leo, A.; Alhusaini, A.; Soubrane, C.; Mazzarella, E.; Russo, E.; Whalley, B.J.; Di Marzo, V.; Stephens, G.J. Nonpsychotropic plant cannabinoids, cannabidivarin (CBDV) and cannabidiol (CBD), activate and desensitize transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channels in vitro: Potential for the treatment of neuronal hyperexcitability. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, E.M.; Sticht, M.A.; Duncan, M.; Stott, C.; Parker, L.A. Evaluation of the potential of the phytocannabinoids, cannabidivarin (CBDV) and Delta(9) -tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), to produce CB1 receptor inverse agonism symptoms of nausea in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthaler, S.; Pohn, B.; Kolmanz, C.; Huu, C.N.; Krewenka, C.; Huber, A.; Kranner, B.; Rausch, W.D.; Moldzio, R. Differences in receptor binding affinity of several phytocannabinoids do not explain their effects on neural cell cultures. Neurotoxicology Teratol. 2014, 46, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Allarà, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, B.K.; Wager-Miller, J.; Haskins, C.; Straiker, A.; Mackie, K. Functional selectivity in CB(2) cannabinoid receptor signaling and regulation: Implications for the therapeutic potential of CB(2) ligands. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 81, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng-Crank, J.; Foster, C.D.; Krause, J.D.; Mertz, R.; Godinot, N.; DiChiara, T.J.; Reinhart, P.H. Cloning, expression, and distribution of functionally distinct Ca2+-activated K+ channel isoforms from human brain. Neuron 1994, 13, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrik, D.; Brenner, R. Regulation of STREX exon large conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels by the beta4 accessory subunit. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weiger, T.M.; Holmqvist, M.H.; Levitan, I.B.; Clark, F.T.; Sprague, S.; Huang, W.J.; Glucksmann, M.A. A novel nervous system β subunit that downregulates human large conductance calcium-dependent potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 3563–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Shao, L.R.; Chavoshy, S.; Gu, N.; Trieb, M.; Behrens, R.; Storm, J.F. Presynaptic Ca2+-activated K+ channels in glutamatergic hippocampal terminals and their role in spike repolarization and regulation of transmitter release. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 9585–9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallner, M.; Meera, P.; Toro, L. Determinant for β-subunit regulation in high-conductance voltage-activated and Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels: An additional transmembrane region at the N terminus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14922–14927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salkoff, L.; Butler, A.; Ferreira, G.; Santi, C.; Wei, A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkefeld, H.; Sailer, C.A.; Bildl, W.; Rohde, V.; Thumfart, J.O.; Eble, S.; Klugbauer, N.; Reisinger, E.; Bischofberger, J.; Oliver, D.; et al. BKCa-Cav channel complexes mediate rapid and localized Ca2+-activated K+ signaling. Science 2006, 314, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkefeld, H.; Fakler, B. Ligand-gating by Ca2+ is rate limiting for physiological operation of BK(Ca) channels. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 7358–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kshatri, A.; Cerrada, A.; Gimeno, R.; Bartolomé-Martín, D.; Rojas, P.; Giraldez, T. Differential regulation of BK channels by fragile X mental retardation protein. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152, e201912502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon, M.; Cantor, R.M.; Liu, J.; Gilliam, T.C.; Geschwind, D.H.; Autism Genetic Research Exchange, C. Evidence for a language quantitative trait locus on chromosome 7q in multiplex autism families. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 70, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Molecular Genetic Study of Autism. A genomewide screen for autism: Strong evidence for linkage to chromosomes 2q, 7q, and 16p. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrick, L.K.; Deng, P.Y.; Hashimoto, H.; Oh, Y.M.; Cho, Y.; Poidevin, M.J.; Suhl, J.A.; Visootsak, J.; Cavalli, V.; Jin, P.; et al. Independent role for presynaptic FMRP revealed by an FMR1 missense mutation associated with intellectual disability and seizures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.Y.; Klyachko, V.A. Genetic upregulation of BK channel activity normalizes multiple synaptic and circuit defects in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Typlt, M.; Mirkowski, M.; Azzopardi, E.; Ruettiger, L.; Ruth, P.; Schmid, S. Mice with deficient BK channel function show impaired prepulse inhibition and spatial learning, but normal working and spatial reference memory. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e081270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, A.I.; Panasiuk, O.; Drachuk, K.; Montecucco, F.; Brandt, K.J.; Mach, F. The quest for endothelial atypical cannabinoid receptor: BKCa channels act as cellular sensors for cannabinoids in in vitro and in situ endothelial cells. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade, H.; Muraki, K.; Ohya, S.; Hatano, N.; Imaizumi, Y. Activation of large-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels by cannabinoids. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 290, C77–C86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.S. BMS-204352: A potassium channel opener developed for the treatment of stroke. CNS Drug Rev. 2002, 8, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno-Munoz, M.I.; Martins, F.; Medrano, M.C.; Aloisi, E.; Pietropaolo, S.; Dechaud, C.; Subashi, E.; Bony, G.; Ginger, M.; Moujahid, A.; et al. Potential Involvement of Impaired BKCa Channel Function in Sensory Defensiveness and Some Behavioral Disturbances Induced by Unfamiliar Environment in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catterall, W.A.; Few, A.P. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron 2008, 59, 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.J.; Adams, M.E.; Dunlap, K. Multiple Ca2+ channel types coexist to regulate synaptosomal neurotransmitter release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9518–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Long, L.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Hu, H.; Soong, T.; Tang, F. Nuclear localization of Cav2. 2 and its distribution in the mouse central nervous system, and changes in the hippocampus during and after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2010, 36, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyes, S.; Pratt, W.S.; Rees, E.; Dahimene, S.; Ferron, L.; Owen, M.J.; Dolphin, A.C. Genetic disruption of voltage-gated calcium channels in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 134, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsenko, S.A.; Hixson, P.; Roney, E.K.; Scott, D.A.; Schaaf, C.P.; Ng, Y.-t.; Palmer, R.; Fisher, R.B.; Patel, A.; Cheung, S.W. Human subtelomeric copy number gains suggest a DNA replication mechanism for formation: Beyond breakage–fusion–bridge for telomere stabilization. Hum. Genet. 2012, 131, 1895–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, L.; Papaleo, V.; Porcelli, V.; Scarcia, P.; Gaita, L.; Sacco, R.; Hager, J.; Rousseau, F.; Curatolo, P.; Manzi, B. Altered calcium homeostasis in autism-spectrum disorders: Evidence from biochemical and genetic studies of the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier AGC1. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffuri, A.L.; Ladarre, D.; Lenkei, Z. Type-1 cannabinoid receptor signaling in neuronal development. Pharmacology 2012, 90, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karhson, D.S.; Hardan, A.Y.; Parker, K.J. Endocannabinoid signaling in social functioning: An RDoC perspective. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Li, D.; Li, L.; Wu, L.; Sun, C. Role of the endocannabinoid system in neurological disorders. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2019, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fyke, W.; Velinov, M. FMR1 and Autism, an Intriguing Connection Revisited. Genes 2021, 12, 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12081218

Fyke W, Velinov M. FMR1 and Autism, an Intriguing Connection Revisited. Genes. 2021; 12(8):1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12081218

Chicago/Turabian StyleFyke, William, and Milen Velinov. 2021. "FMR1 and Autism, an Intriguing Connection Revisited" Genes 12, no. 8: 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12081218

APA StyleFyke, W., & Velinov, M. (2021). FMR1 and Autism, an Intriguing Connection Revisited. Genes, 12(8), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12081218