Aliarcobacter butzleri from Water Poultry: Insights into Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence and Heavy Metal Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culturing and Identification

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.3. DNA Extraction and Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatic Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

3.2. Genome Assembly

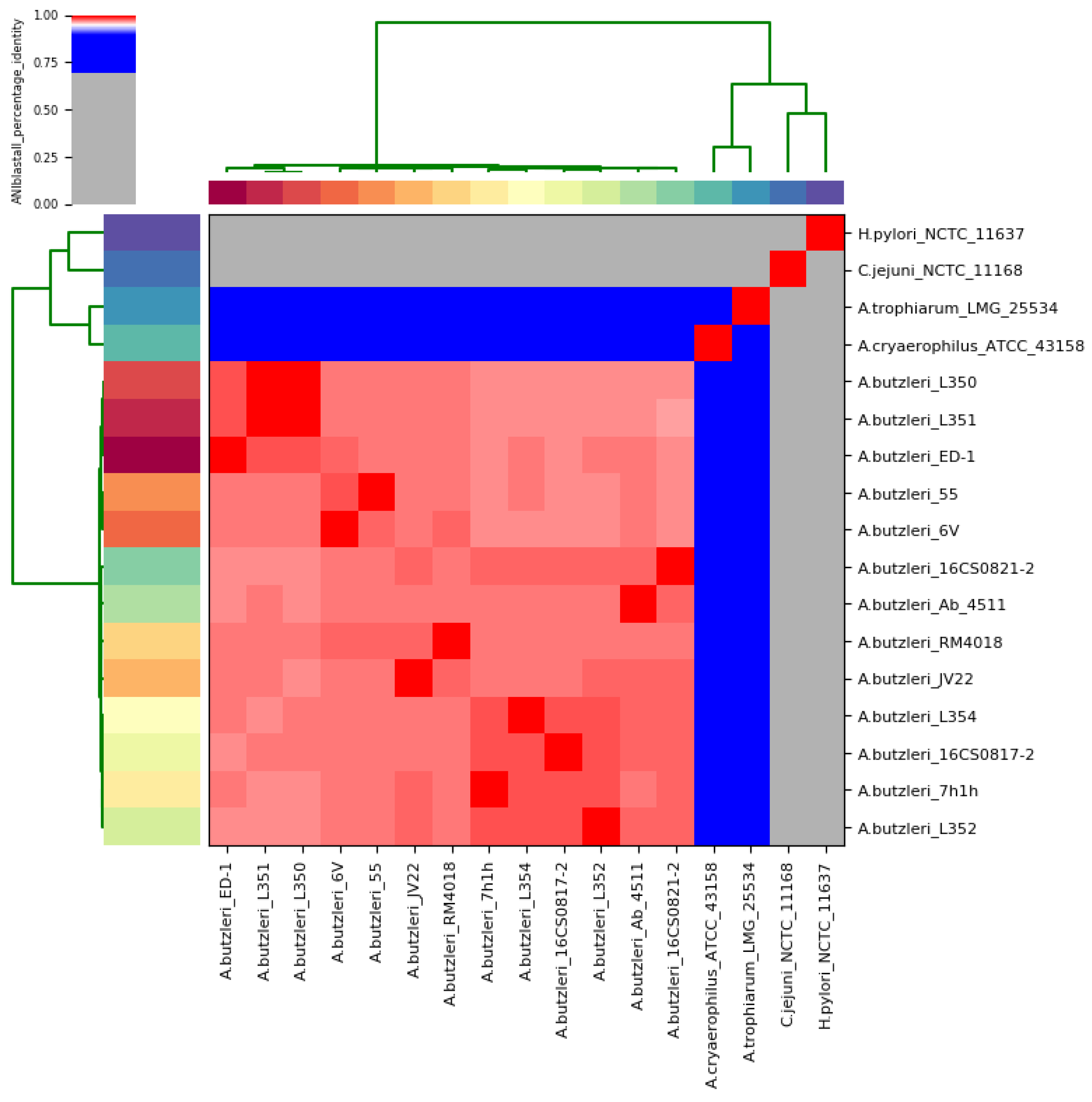

3.3. Taxonomic Classification of the Whole-Genome Sequence Data

3.4. AMR and Heavy Metal Resistance Genes

3.5. Virulence-Associated Genes

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vandamme, P.; Falsen, E.; Rossau, R.; Hoste, B.; Segers, P.; Tytgat, R.; De Ley, J. Revision of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella taxonomy: Emendation of generic descriptions and proposal of Arcobacter gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1991, 41, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Salas-Masso, N.; Dieguez, A.L.; Balboa, S.; Lema, A.; Romalde, J.L.; Figueras, M.J. Revisiting the Taxonomy of the Genus Arcobacter: Getting Order From the Chaos. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Salas-Masso, N.; Dieguez, A.L.; Balboa, S.; Lema, A.; Romalde, J.L.; Figueras, M.J. Corrigendum: Revisiting the Taxonomy of the Genus Arcobacter: Getting Order From the Chaos. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Salas-Masso, N.; Dieguez, A.L.; Balboa, S.; Lema, A.; Romalde, J.L.; Figueras, M.J. Corrigendum (2): Revisiting the Taxonomy of the Genus Arcobacter: Getting Order From the Chaos. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Salas-Masso, N.; Figueras, M.J. Arcobacter lacus sp. nov. and Arcobacter caeni sp. nov., two novel species isolated from reclaimed water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 3326–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, L.; Figueras, M.J. Taxonomy, epidemiology, and clinical relevance of the genus Arcobacter. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramees, T.P.; Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Rathore, R.S.; Kumar, A.; Saminathan, M.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.K. Arcobacter: An emerging food-borne zoonotic pathogen, its public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control—A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2017, 37, 136–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucker, R.; Troeger, H.; Kleer, J.; Fromm, M.; Schulzke, J.D. Arcobacter butzleri induces barrier dysfunction in intestinal HT-29/B6 cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, O.; Dediste, A.; Houf, K.; Ibekwem, S.; Souayah, H.; Cadranel, S.; Douat, N.; Zissis, G.; Butzler, J.P.; Vandamme, P. Arcobacter species in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1863–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Teng, J.L.; Leung, K.W.; Yuen, K.Y. Identification by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of Arcobacter butzleri bacteraemia in a patient with acute gangrenous appendicitis. Mol. Pathol. 2002, 55, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Driessche, E.; Houf, K.; van Hoof, J.; De Zutter, L.; Vandamme, P. Isolation of Arcobacter species from animal feces. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 229, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabay, H.I.; Unver, A.; Sahin, M.; Otlu, S.; Elmali, M.; Yaman, H. Isolation of various Arcobacter species from domestic geese (Anser anser). Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 128, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lehner, A.; Tasara, T.; Stephan, R. Relevant aspects of Arcobacter spp. as potential foodborne pathogen. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 102, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilmen, S.; Vural, A.; Erkan, M.E.; Yildirim, I.H. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Arcobacter species in cow milk, water buffalo milk and fresh village cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 188, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausdorf, L.; Neumann, M.; Bergmann, I.; Sobiella, K.; Mundt, K.; Frohling, A.; Schluter, O.; Klocke, M. Occurrence and genetic diversity of Arcobacter spp. in a spinach-processing plant and evaluation of two Arcobacter-specific quantitative PCR assays. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, F.; Di Pinto, A.; Mottola, A.; Mule, G.; Chieffi, D.; Baruzzi, F.; Tantillo, G.; Fusco, V. Genomic Characterization of Arcobacter butzleri Isolated From Shellfish: Novel Insight Into Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Determinants. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.T.K.; Lipman, L.J.A.; Gaastra, W. Arcobacter, what is known and unknown about a potential foodborne zoonotic agent! Vet. Microbiol. 2006, 115, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.H.; Saleha, A.A.; Zunita, Z.; Cheah, Y.K.; Murugaiyah, M.; Korejo, N.A. Genetic characterization of Arcobacter isolates from various sources. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 160, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Queiroz, J.A.; Oleastro, M.; Domingues, F.C. Insights in the pathogenesis and resistance of Arcobacter: A review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacometti, F.; Lucchi, A.; Di Francesco, A.; Delogu, M.; Grilli, E.; Guarniero, I.; Stancampiano, L.; Manfreda, G.; Merialdi, G.; Serraino, A. Arcobacter butzleri, Arcobacter cryaerophilus, and Arcobacter skirrowii Circulation in a Dairy Farm and Sources of Milk Contamination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 5055–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fera, M.T.; La Camera, E.; Carbone, M.; Malara, D.; Pennisi, M.G. Pet cats as carriers of Arcobacter spp. in Southern Italy. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICMSF. Microorganisms in Foods 7. Microbiological Testing in Food Safety Management; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T.K.; Lipman, L.J.; van der Graaf-van Bloois, L.; van Bergen, M.; Gaastra, W. Potential routes of acquisition of Arcobacter species by piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 2006, 114, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isidro, J.; Ferreira, S.; Pinto, M.; Domingues, F.; Oleastro, M.; Gomes, J.P.; Borges, V. Virulence and antibiotic resistance plasticity of Arcobacter butzleri: Insights on the genomic diversity of an emerging human pathogen. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 80, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli, F.; Chieffi, D.; Di Pinto, A.; Mottola, A.; Baruzzi, F.; Fusco, V. Phenotype and genomic background of Arcobacter butzleri strains and taxogenomic assessment of the species. Food Microbiol. 2020, 89, 103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merga, J.Y.; Williams, N.J.; Miller, W.G.; Leatherbarrow, A.J.; Bennett, M.; Hall, N.; Ashelford, K.E.; Winstanley, C. Exploring the diversity of Arcobacter butzleri from cattle in the UK using MLST and whole genome sequencing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelbaqi, K.; Menard, A.; Prouzet-Mauleon, V.; Bringaud, F.; Lehours, P.; Megraud, F. Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene of Arcobacter species and characterization of human ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 49, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, A.; Capozzi, L.; Bianco, A.; Caruso, M.; Latorre, L.; Costa, A.; Giannico, A.; Ridolfi, D.; Bulzacchelli, C.; Santagada, G. Identification of virulence and antibiotic resistance factors in Arcobacter butzleri isolated from bovine milk by Whole Genome Sequencing. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2019, 8, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.G.; Parker, C.T.; Rubenfield, M.; Mendz, G.L.; Wosten, M.M.; Ussery, D.W.; Stolz, J.F.; Binnewies, T.T.; Hallin, P.F.; Wang, G.; et al. The complete genome sequence and analysis of the epsilonproteobacterium Arcobacter butzleri. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashker, M.; Gwida, M.; Tomaso, H.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R.; El-Gohary, F.; Hotzel, H. Staphylococci in cattle and buffaloes with mastitis in Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 7450–7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänel, I.; Hotzel, H.; Tomaso, H.; Busch, A. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Genomic Structure of Arcobacter skirrowii Isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houf, K.; Tutenel, A.; De Zutter, L.; Van Hoof, J.; Vandamme, P. Development of a multiplex PCR assay for the simultaneous detection and identification of Arcobacter butzleri, Arcobacter cryaerophilus and Arcobacter skirrowii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 193, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUCAST. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 9.0. 2019. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- European Food Safety Authority; Aerts, M.; Battisti, A.; Hendriksen, R.; Kempf, I.; Teale, C.; Tenhagen, B.-A.; Veldman, K.; Wasyl, D.; Guerra, B.; et al. Technical specifications on harmonised monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from food-producing animals and food. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Salzberg, S.L. Kraken: Ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.; Glover, R.H.; Humphris, S.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Toth, I.K. Genomics and taxonomy in diagnostics for food security: Soft-rotting enterobacterial plant pathogens. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Goker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C.J. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, B.; Raphenya, A.R.; Alcock, B.; Waglechner, N.; Guo, P.; Tsang, K.K.; Lago, B.A.; Dave, B.M.; Pereira, S.; Sharma, A.N.; et al. CARD 2017: Expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D566–D573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Padmanabhan, B.R.; Diene, S.M.; Lopez-Rojas, R.; Kempf, M.; Landraud, L.; Rolain, J.M. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Haft, D.H.; Prasad, A.B.; Slotta, D.J.; Tolstoy, I.; Tyson, G.H.; Zhao, S.; Hsu, C.-H.; McDermott, P.F.; et al. Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00483-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levican, A.; Figueras, M.J. Performance of five molecular methods for monitoring Arcobacter spp. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Fraqueza, M.J.; Queiroz, J.A.; Domingues, F.C.; Oleastro, M. Genetic diversity, antibiotic resistance and biofilm-forming ability of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from poultry and environment from a Portuguese slaughterhouse. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 162, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayman, T.; Abay, S.; Hizlisoy, H.; Atabay, H.I.; Diker, K.S.; Aydin, F. Emerging pathogen Arcobacter spp. in acute gastroenteritis: Molecular identification, antibiotic susceptibilities and genotyping of the isolated arcobacters. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, S.; Kayman, T.; Hizlisoy, H.; Aydin, F. In vitro antibacterial susceptibility of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from different sources. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2012, 74, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shah, A.H.; Saleha, A.A.; Zunita, Z.; Murugaiyah, M.; Aliyu, A.B. Antimicrobial susceptibility of an emergent zoonotic pathogen, Arcobacter butzleri. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 40, 569–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.; Luis, A.; Oleastro, M.; Pereira, L.; Domingues, F.C. A meta-analytic perspective on Arcobacter spp. antibiotic resistance. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 16, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathlavath, S.; Kohli, V.; Singh, A.S.; Lekshmi, M.; Tripathi, G.; Kumar, S.; Nayak, B.B. Virulence genotypes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from seafood and its environment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 263, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Abeele, A.M.; Vogelaers, D.; Vanlaere, E.; Houf, K. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus strains isolated from Belgian patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Oleastro, M.; Domingues, F.C. Occurrence, genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance of Arcobacter sp. in a dairy plant. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenberg, A.; Fromke, C.; Stingl, K.; Fessler, A.T.; Golz, G.; Glocker, E.O.; Kreienbrock, L.; Klarmann, D.; Werckenthin, C.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri: Development and application of a new protocol for broth microdilution. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2769–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goris, J.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Klappenbach, J.A.; Coenye, T.; Vandamme, P.; Tiedje, J.M. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rossello-Mora, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, L.G.; Brenner, D.J.; Colwell, R.R.; Grimont, P.A.D.; Kandler, O.; Krichevsky, M.I.; Moore, L.H.; Moore, W.E.C.; Murray, R.G.E.; Stackebrandt, E.; et al. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1987, 37, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On, S.L.W.; Miller, W.G.; Houf, K.; Fox, J.G.; Vandamme, P. Minimal standards for describing new species belonging to the families Campylobacteraceae and Helicobacteraceae: Campylobacter, Arcobacter, Helicobacter and Wolinella spp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 5296–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, B.P.; Guay, G.G. Gene amplification contributes to sulfonamide resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 2042–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, M.A.; Piddock, L.J. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, A. MarR family transcription factors. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R142–R143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casabon, I.; Zhu, S.H.; Otani, H.; Liu, J.; Mohn, W.W.; Eltis, L.D. Regulation of the KstR2 regulon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a cholesterol catabolite. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 89, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, T.H. Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhadidy, M.; Ali, M.M.; El-Shibiny, A.; Miller, W.G.; Elkhatib, W.F.; Botteldoorn, N.; Dierick, K. Antimicrobial resistance patterns and molecular resistance markers of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from human diarrheal cases. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, J. Antimicrobial Resistance in Campylobacter spp. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopapadakou, N.H. Penicillin-binding proteins and bacterial resistance to β-lactams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993, 37, 2045–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Correia, D.R.; Oleastro, M.; Domingues, F.C. Arcobacter butzleri Ciprofloxacin Resistance: Point Mutations in DNA Gyrase A and Role on Fitness Cost. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonneuve, E.; Shakespeare, L.J.; Jorgensen, M.G.; Gerdes, K. Bacterial persistence by RNA endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13206–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K. Persister cells and the riddle of biofilm survival. Biochemistry 2005, 70, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Boto, D.; Lopez-Portoles, J.A.; Simon, C.; Valdezate, S.; Echeita, M.A. Study of the molecular mechanisms involved in high-level macrolide resistance of Spanish Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2083–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolinger, H.; Kathariou, S. The Current State of Macrolide Resistance in Campylobacter spp.: Trends and Impacts of Resistance Mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, M.A.; Piro, K.M.; Xu, W.; Hansen, S.; Lewis, K.; Brennan, R.G. Molecular mechanisms of HipA-mediated multidrug tolerance and its neutralization by HipB. Science 2009, 323, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Fekih, I.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.P.; Zhao, Y.; Alwathnani, H.A.; Saquib, Q.; Rensing, C.; Cervantes, C. Distribution of Arsenic Resistance Genes in Prokaryotes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, S.; Deppenmeier, U.; Gunsalus, R.P. Regulation of the molybdate transport operon, modABCD, of Escherichia coli in response to molybdate availability. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, H.; Pantel, I.; Lindgren, P.E.; Gotz, F. Characterization of the molybdate transport system ModABC of Staphylococcus carnosus. Arch. Microbiol. 1999, 172, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiethaus, J.; Wirsing, A.; Narberhaus, F.; Masepohl, B. Overlapping and specialized functions of the molybdenum-dependent regulators MopA and MopB in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 8441–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gupta, N.; Maurya, S.; Verma, H.; Verma, V.K. Unraveling the factors and mechanism involved in persistence: Host-pathogen interactions in Helicobacter pylori. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 18572–18587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial toxins in sepsis: A brief review. Virulence 2014, 5, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emiola, A.; George, J.; Andrews, S.S. A Complete Pathway Model for Lipid A Biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2014, 10, e0121216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opiyo, S.O.; Pardy, R.L.; Moriyama, H.; Moriyama, E.N. Evolution of the Kdo2-lipid A biosynthesis in bacteria. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovetto, F.; Carlier, A.; Van den Abeele, A.M.; Illeghems, K.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Cocolin, L.; Houf, K. Characterization of the emerging zoonotic pathogen Arcobacter thereius by whole genome sequencing and comparative genomics. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronow, S.; Brabetz, W.; Brade, H. Comparative functional characterization in vitro of heptosyltransferase I (WaaC) and II (WaaF) from Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 6602–6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadas, G.; Sharbati, S.; Hanel, I.; Messelhausser, U.; Glocker, E.; Alter, T.; Golz, G. Presence of virulence genes, adhesion and invasion of Arcobacter butzleri. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douidah, L.; de Zutter, L.; Bare, J.; De Vos, P.; Vandamme, P.; Vandenberg, O.; Van den Abeele, A.M.; Houf, K. Occurrence of putative virulence genes in Arcobacter species isolated from humans and animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, D.W.; Tharp, B.B.; Konisky, J. Cloning and promoter identification of the iron-regulated cir gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 5343–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Kaito, C.; Morishita, D.; Kurokawa, K.; Sekimizu, K. Regulation of exoprotein gene expression by the Staphylococcus aureus cvfB gene. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 1964–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, B.; Sasakawa, C.; Tobe, T.; Makino, S.; Komatsu, K.; Yoshikawa, M. A dual transcriptional activation system for the 230 kb plasmid genes coding for virulence-associated antigens of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 1989, 3, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobe, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Mizuno, T.; Sasakawa, C. Transcriptional control of the invasion regulatory gene virB of Shigella flexneri: Activation by VirF and repression by H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 6142–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | ERY | CIP | DC | TET | GM | SM | AMP | CTX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16CS0817-2 | S (2 mg/L) | S (0.03 mg/L) | S (1.5 mg/L) | S (2 mg/L) | S (1.5 mg/L) | R (6 mg/L) | S (4 mg/L) | R (32 mg/L) |

| 16CS0821-2 | R (40 mg/L) | S (0.38 mg/L) | R (4 mg/L) | R (3 mg/L) | S (1.5 mg/L) | R (12 mg/L) | S (4 mg/L) | R (32 mg/L) |

| Assembly | 16CS0817-2 | 16CS0821-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Total length | 2,432,983 | 2,121,905 |

| GC (%) | 26.97 | 27.01 |

| Nr. of contigs | 89 | 52 |

| Largest contig | 159,485 | 177,585 |

| N50 | 62,983 | 69,691 |

| Predicted genes | 2500 | 2159 |

| CDS | 2451 | 2110 |

| rRNA | 3 (5S,16S, 23S) | 3 (5S, 16S, 23S) |

| tRNA | 46 | 46 |

| tmRNA | 1 | 1 |

| Strain | Species | Aliarcobacter butzleri RM4018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identities/HSP Length | Difference in % G + C (≤1 Either Distinct or Same Species; >1 Distinct Species) | |||

| Distance | DDH Estimate (GLM-Based) | |||

| 16CS0817-2 | A. butzleri | 0.0248 | 78.80% [75.8–81.4%] | 0.07 |

| 16CS0821-2 | A. butzleri | 0.0238 | 79.70% [76.7–82.3%] | 0.04 |

| 6V | A. butzleri | 0.0222 | 81.00% [78–83.6%] | 0.20 |

| 55 | A. butzleri | 0.0219 | 81.20% [78.3–83.8%] | 0.26 |

| 7h1h | A. butzleri | 0.0242 | 79.30% [76.3–81.9%] | 0.01 |

| Ab_4511 | A. butzleri | 0.0239 | 79.50% [76.6–82.2%] | 0.09 |

| ED-1 | A. butzleri | 0.0247 | 78.90% [75.9–81.6%] | 0.16 |

| JV22 | A. butzleri | 0.0218 | 81.40% [78.5–83.9%] | 0.03 |

| L350 | A. butzleri | 0.0254 | 78.30% [75.3–81%] | 0.10 |

| L351 | A. butzleri | 0.0253 | 78.40% [75.4–81.1%] | 0.06 |

| L352 | A. butzleri | 0.0237 | 79.70% [76.8–82.4%] | 0.03 |

| L354 | A. butzleri | 0.0252 | 78.50% [75.5–81.2%] | 0.11 |

| ATCC 43158 | A. cryaerophilus | 0.2025 | 21.70% [19.4–24.1%] | 0.42 |

| LMG 25534 | A. trophiarum | 0.2101 | 20.90% [18.7–23.3%] | 1.17 |

| NCTC 11168 | C. jejuni subsp. jejuni | 0.2010 | 21.80% [19.6–24.3%] | 3.50 |

| NCTC 11637 | H. pylori | 0.1699 | 25.60% [23.2–28.1%] | 11.78 |

| Strain | aspA | atpA | glnA | gltA | glyA | pgm | tkt | ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16CS0817-2 | 177 | 39 | 40 | 123 | new allele | 194 | 24 | new |

| 16CS0821-2 | 47 | 217 | 4 | 129 | new allele | 123 | 37 | new |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Müller, E.; Abdel-Glil, M.Y.; Hotzel, H.; Hänel, I.; Tomaso, H. Aliarcobacter butzleri from Water Poultry: Insights into Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence and Heavy Metal Resistance. Genes 2020, 11, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091104

Müller E, Abdel-Glil MY, Hotzel H, Hänel I, Tomaso H. Aliarcobacter butzleri from Water Poultry: Insights into Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence and Heavy Metal Resistance. Genes. 2020; 11(9):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091104

Chicago/Turabian StyleMüller, Eva, Mostafa Y. Abdel-Glil, Helmut Hotzel, Ingrid Hänel, and Herbert Tomaso. 2020. "Aliarcobacter butzleri from Water Poultry: Insights into Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence and Heavy Metal Resistance" Genes 11, no. 9: 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091104

APA StyleMüller, E., Abdel-Glil, M. Y., Hotzel, H., Hänel, I., & Tomaso, H. (2020). Aliarcobacter butzleri from Water Poultry: Insights into Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence and Heavy Metal Resistance. Genes, 11(9), 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091104