1. Circular Strategies for Plastic: Concepts and Global Context

The circular economy (CE) represents a systemic shift from traditional linear production models toward regenerative cycles in which materials retain value for as long as possible. This transition relies on strategies such as reuse, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing, and recycling, aiming to minimize waste generation and extend product lifetimes through multiple value loops [

1]. In plastics, the relevance of circularity becomes particularly evident when considering the material’s history: early biobased materials (e.g., natural rubber and shellac) were progressively replaced by synthetic polymers that, during and after the Second World War, were engineered to be lightweight, durable, hygienic, chemically resistant, and easily manufacturable at scale [

2]. These advantages accelerated global demand and positioned plastics as indispensable in modern life, while simultaneously entrenching highly linear patterns of production and disposal.

Since the 1950s, plastic production has increased more than 230-fold, reaching nearly 400 Mt in 2022, while recycling rates remain below 10% and landfilling persists as the dominant waste pathway in many regions [

3]. While plastic pollution is often associated with post-consumer residues, a substantial share of plastic volume accumulates before products even reach use. Industrial surpluses, idle inventories, and stockpiled goods contribute to long-term material accumulation, creating a hidden reservoir of future waste that is rarely considered in conventional waste models. As shown by Geyer et al. [

4] in 2015, 105 Mt of plastics entered global stock without fulfilling their intended functions, highlighting the need for early recovery strategies, improved resource stewardship, and stronger traceability across supply chains.

The scale of the challenge is amplified by the dominance of a limited set of polymers—PE, PP, PET, PVC, PS, HDPE, and LDPE—across packaging, construction, textiles, automotive, and electronics. Regulatory and societal drivers are increasingly shaping circular strategies for automotive plastics. Vehicles are long-lived, high-volume products whose growing polymer content aligns with public expectations for sustainable mobility, climate objectives, and resource-security concerns. Societal drivers are increasingly shaping circular strategies for automotive plastics.

These societal and policy pressures have increasingly translated into regulatory “market-pull” instruments that reshape circular priorities in downstream manufacturing sectors. In the European Union, the ongoing revision of end-of-life vehicle (ELV) rules has been framed not only as a waste-management measure but also as a circularity and traceability intervention responding to public expectations, climate commitments, and concerns about material security and value leakage. Within this context, policymakers have advanced mandatory minimum recycled plastic content targets for new vehicles (including a 25% target under discussion in the legislative process, with intermediate targets and provisions to promote closed-loop recycling), aiming to create stable demand for high-quality recyclates and incentivize investment in advanced sorting, decontamination, and quality-assurance infrastructures. This example illustrates that circular strategies are shaped by human lifestyles and consumption patterns—such as mobility demand and product longevity—alongside governance mechanisms that determine which circular pathways are feasible at scale. While automotive initiatives highlight the role of policy-driven demand for high-specification recyclates, the most significant mass flows and most immediate circularity bottlenecks remain concentrated in packaging streams, where material complexity and contamination frequently constrain mechanical recovery [

5,

6].

The packaging sector alone accounts for ~40% of annual production, but multilayer structures, pigments, additives, and volatile compounds significantly hinder recyclability and contaminate material streams, reducing the effectiveness and economics of mechanical recovery [

3,

7,

8]. In parallel, environmental and health risks add another layer of complexity [

9]. Plastic pollution affects terrestrial and aquatic environments, and microplastics and nanoplastics raise concerns due to their mobility, bioaccumulation potential, and capacity to transport harmful additives or absorbed toxins [

9,

10]. Degradation processes—including thermal oxidation, UV-induced fragmentation, and biological weathering—can also release greenhouse gases such as CO

2, linking plastic mismanagement to climate change [

8,

11]. These considerations reinforce the need to expand the focus on circularity from end-of-life management to full-life-cycle optimization, encompassing product design, material selection, performance during use, and emissions control throughout the system [

12].

Circularity in plastics is commonly conceptualized through circulation loops that define how value can be retained over multiple cycles. As outlined by Bucknall [

3] and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [

13], these loops range from prevention through ecodesign and reuse, to mechanical recycling, upcycling, and chemical or biological depolymerization, with energy recovery as a last resort. Because each loop requires specific interventions, infrastructure, and quality thresholds, it is essential to understand their interactions and limitations before examining contemporary CE models or proposing new technological strategies.

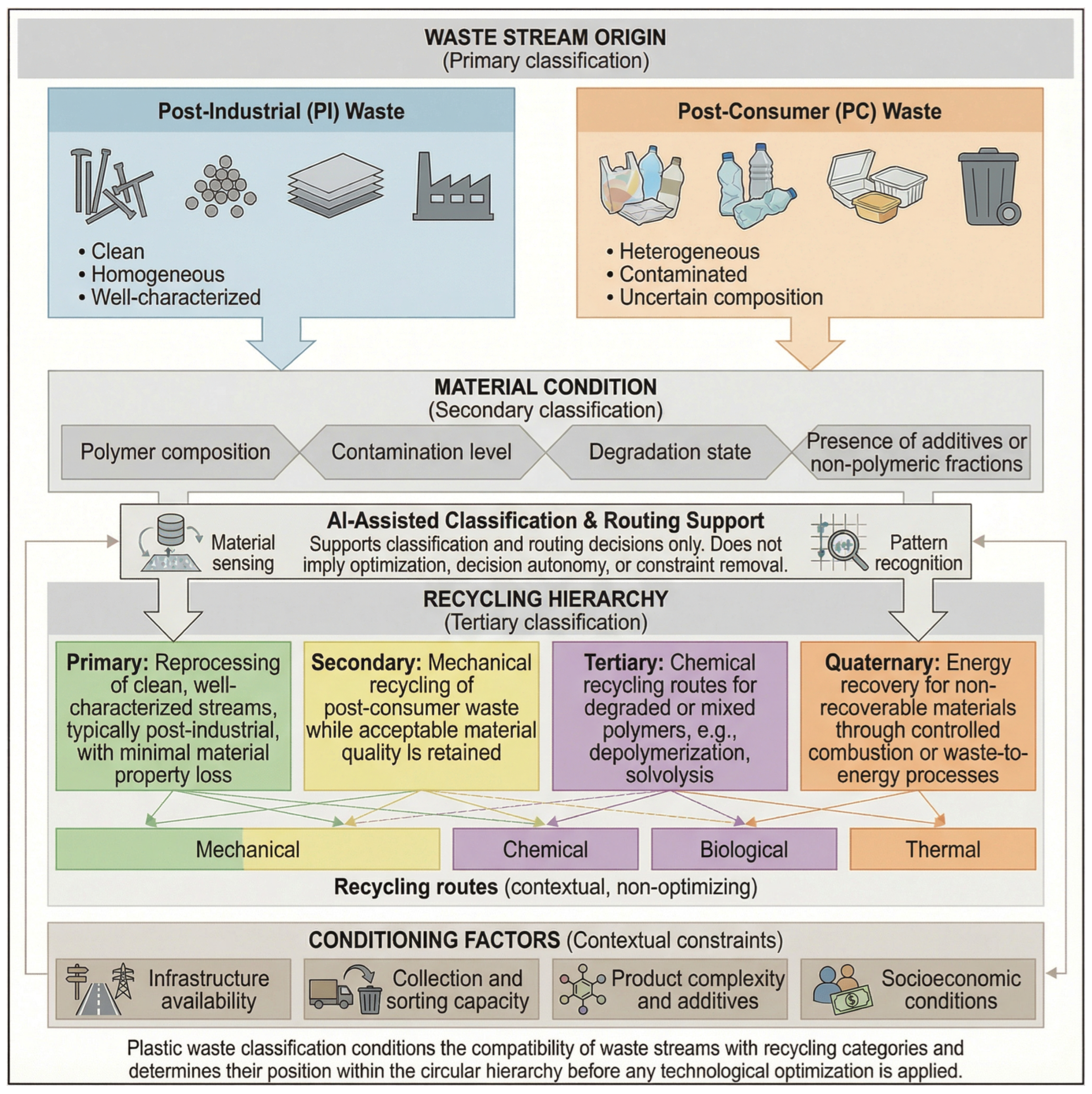

From an operational standpoint, “plastic waste” is not a single feedstock but a spectrum of streams with distinct compositions, contamination levels, and degradation histories that directly constrain sorting performance, recycling yields, and product quality. Here, we propose a pragmatic classification by origin and complexity: (i) pre-consumer industrial scrap (narrow polymer distribution, low contamination) [

14]; (ii) post-consumer packaging (high volume, high heterogeneity, frequent multilayers and additives) [

15]; (iii) WEEE/ELV plastics (waste electrical and electronic equipment/end-of-life vehicles; engineering polymers, flame retardants, fillers, legacy additives) [

16]; (iv) construction/demolition plastics (weathered, filled, mixed with inorganics) [

17]. Across all classes, four feedstock descriptors should be reported where possible: polymer mix, format (rigid vs. film/flexible), contamination (food/soil/labels/moisture), and degradation/additive fingerprint (oxidation, pigments, fillers, stabilizers). These descriptors define the feasible circular pathway (mechanical, chemical, or biological) and the realistic substitution potential of recyclates. More broadly, the tendency toward quality loss across repeated cycles motivates tiered recycling strategies and the systematic use of LCA to evaluate trade-offs across pathways and contexts [

18].

Within this evolving landscape, emerging digital technologies—particularly AI—are rapidly transforming circularity practices by enabling data-driven decisions across the plastic value chain. In this review, AI is considered in a functional sense as a set of methods (e.g., machine learning, computer vision, and optimization) that can improve identification and sorting, predict waste generation and material quality, optimize collection and logistics, and support scenario-based life-cycle modelling under uncertainty [

19]. Recent work illustrates how coupling spectroscopy with ML can materially improve polymer identification under realistic, noisy conditions. For example, interpretable ML (dictionary learning) has been used to separate mixed FTIR signals and improve assignment robustness in microplastic analysis. Hyperspectral/portable NIR systems, supported by multivariate/ML models, enable near-real-time classification in field-relevant settings, although performance remains challenging for carbon-black plastics and thin transparent films. Complementary approaches such as Raman with AI-based preprocessing and LIBS with ML classifiers extend identification capability to heterogeneous and additive-rich streams, motivating the multi-sensor and sensor-fusion architectures reviewed in

Section 2. Significantly, AI’s role is expanding from improving isolated tasks (e.g., classification or process control) toward supporting system-level decision frameworks that integrate material energy, regulatory, and economic constraints. Accordingly, rather than claiming that AI “determines” viability, we argue that AI can increasingly inform and optimize route selection and deployment conditions when coupled with robust sensing, reliable datasets, and transparent governance. This perspective frames the remainder of the review, which examines how AI-enabled processes and AI-enabled systems design can be evaluated and scaled under real-world constraints [

19].

Phase Evolution of AI in Circular Plastic System: From Instrument Support to System Enabler

In circular plastic systems, AI has evolved from improving isolated analytical steps to enabling higher-level system coordination. To clarify this progression, we propose a phased view of AI’s role, which also frames the structure of this review.

Phase I—Instrument support (task-level assistance): AI is primarily used to enhance measurement interpretation and classification in constrained settings (e.g., supervised models for FTIR/NIR/Raman spectra, baseline correction, denoising, peak attribution, and particle recognition). The value proposition is improved speed and accuracy for polymer identification and sorting decisions at the unit-operation level.

Phase II—Process optimization (line-level control): AI expands to optimize operational parameters and quality outcomes across a process line (e.g., multi-sensor decision rules, contamination detection, dynamic thresholding, predictive maintenance, and yield/quality optimization under variable feedstock). Here, AI links sensing to actuation, improving throughput and reducing mis-sorts, rejects, and energy penalties.

Phase III—System orchestration (network-level routing): AI supports routing and planning across collection, sorting, and recycling networks by integrating heterogeneous data streams (material composition, degradation/additive fingerprints, logistics constraints, market specifications, and environmental metrics). In this phase, AI functions as a decision-support layer for choosing among mechanical, chemical, biological, and energy-recovery pathways under uncertainty, often coupled with scenario-based LCA/TEA.

Phase IV—Structural enabler (design and governance integration): AI contributes to system design by enabling continuous updating of circular strategies through feedback loops, digital traceability, and governance-aligned optimization. Rather than optimizing a fixed process, AI helps define which routes are feasible, where they should be deployed, and under what compliance and monitoring requirements. This phase requires reliable datasets, transparency, and robust governance to avoid bias, ensure accountability, and maintain trust in automated decisions.

This phased lens connects the review’s technical sections (advanced sensing and AI-enabled sorting) with broader system-level considerations (routing, techno-economic and environmental trade-offs, and policy/traceability constraints), ensuring that AI’s role is discussed consistently from instruments to infrastructure-scale circularity.

2. Advanced Sensing and Intelligent Sorting of Plastics

2.1. The Strategic Role of Intelligent Sorting in Circular Plastic Systems

Plastic waste classification is a decisive stage in circular valorization pathways because it determines the quality of recovered materials and, ultimately, the feasibility of reintegration into mechanical, chemical, and upcycling routes. These routes differ markedly in process complexity, energy demand, emissions profiles, and tolerance to feedstock heterogeneity. As summarized by Naeim et al. [

20], plastic can be managed through mechanical, chemical, thermal, physical, and biological processes, each with specific advantages and operational constraints closely linked to polymer purity, degradation state, and contamination levels.

In practice, mechanical recycling is widely adopted due to its relative simplicity and cost advantages, yet it is susceptible to mixed streams, contamination, and cumulative thermal-mechanical degradation. Chemical routes (e.g., pyrolysis, solvolysis, gasification) can tolerate more complex or degraded inputs and may regenerate higher-purity intermediates, but typically require higher energy inputs and stricter operating control. Thermal routes prioritize energy recovery for residues that cannot be materially recycled and therefore occupy a lower position in circular hierarchies due to emissions and by-product management requirements. Physical approaches (e.g., grinding, selective dissolution) preserve the polymer backbone but generally require more homogeneous input materials. Biological routes (microbial or enzymatic) are attractive from an environmental perspective; however, slow kinetics and intense sensitivity to contaminants still limit large-scale deployment. This diversity of options reinforces a central point: appropriate classification and sorting are prerequisites for routing each stream toward its most compatible pathway.

The stream origin is equally important for situating recycling strategies within life-cycle conditions. During conversation and manufacturing, virgin polymers generate post-industrial (PI) waste (sprues, trimmings, start-up residues) that typically remains clean, homogeneous, and compositionally known, enabling reintegration into higher-value loops. By contrast, end-of-life materials become post-consumer (PC) waste, which enters management systems as heterogeneous streams with uncertain composition and frequent contamination by organic residues and non-polymeric materials (e.g., paper, mineral particles) [

21]. Accordingly, PI vs. PC origin directly conditions feasible recycling routes and expected quality outcomes.

Recycling pathways are also commonly described in terms of increasing processing intensity: primary recycling is generally limited to clean, well-characterized streams (often PI) that can be reprocessed with minimal processing loss; secondary recycling refers to mechanical treatment of PC waste and remains viable only while material quality is acceptable; tertiary recycling relies on chemical conversion when polymers are degraded or mixed; and quaternary recycling is reserved for functions that cannot be recovered materially, where valorization is limited to controlled energy recovery (e.g., co-incineration or partial oxidation such as gasification) [

22].

System constraints frequently push waste downward in this hierarchy. In many developing contexts, a limited collection and separation infrastructure—combined with socio-economic and demographic factors—results in waste entering recovery systems in more degraded states [

23]. This challenge is compounded by the increasing complexity of plastic products, including additives, blends, and hazardous components that hinder efficient separation [

24,

25,

26]. Additives such as flame retardants, phthalates, bisphenol A, and heavy metals (e.g., cadmium and lead) can reduce recyclate stability and limit safe reuse [

27]. Likewise, multilayer architectures (e.g., carton-based laminates containing paperboard, aluminum, and polyethylene) are challenging to disassemble and often require specialized processing or are routed to lower-value recovery options depending on local capabilities [

28,

29].

Consequently, PC waste frequently appears as highly heterogeneous mixtures with variable contamination, underscoring the need for robust sensing and AI-enabled sorting systems capable of assigning streams to the most compatible valorization pathways. This requirement motivates the advanced sensing and intelligent sorting strategies discussed in the following sections.

2.2. FTIR Spectroscopy and AI-Enhanced Signal Separation

Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is a core technique for polymer identification, owing to characteristic absorption bands in the mid-infrared region (4000–400 cm

−1) [

30]. However, environmental samples often contain sediments, fibers, and organic residues, which can generate overlapping spectra. When microplastic particles are filtered, the membrane itself introduces a confounding spectral signature, further increasing assignment uncertainty.

Beyond these physicochemical interferences, automated FTIR-based identification remains strongly dependent on the availability of curated, representative spectral reference databases. The limited coverage of real-world polymers, additives, and degradation states in existing libraries has been identified as a critical bottleneck for robust classification and large-scale automation [

31].

To address this challenge, Buauk et al. [

32] applied dictionary learning, an interpretable ML technique that decomposes mixed spectra into “spectral atoms” representing filter and polymer contributions. This digital separation reconstructs clean polymer signals even at low concentrations or under noisy conditions. Unlike deep neural networks, dictionary learning retains chemical interpretability and provides transparency into classification decisions—an advantage in regulatory or industrial contexts. These capabilities position FTIR combined with AI as a powerful tool for automated microplastic identification and high-precision sorting.

Despite its high spectral resolution, FTIR deployment beyond laboratory environments remains constrained by instrument cost, system footprint, and sample preparation requirements. In response, FTIR microscopy and imaging approaches have been developed to enable semi-automated analysis of entire filter areas without prior visual sorting. However, the performance of FTIR imaging is strongly dependent on the measurement mode and sample configuration. Transmission-mode FTIR is generally required for reliable detection, as specular reflection modes yield poor results due to weak infrared reflection from polymer surfaces and refraction artifacts caused by irregular particle geometries. At the same time, transmission imaging imposes strict constraints on particle thickness and filter substrates, which must be infrared-transparent and mechanically stable [

33].

2.3. NIR, Minuaturization, and Machine Learning- and AI-Enhanced Signal Separation

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR) has become essential for real-time sorting to device miniaturization, enabling its use outside laboratory environments and into industrial and field settings. Although portable NIR units sacrifice spectral resolution compared with laboratory-grade systems, ML methods partially compensate for incomplete or noisy signals, enabling accurate classification [

34,

35,

36]

Lubongo et al. [

35] demonstrate that hyperspectral NIR combined with multivariate models effectively discriminates polymers such as PE, PP, PET, and PLA. However, classification performance declines markedly for dark-colored plastics and highly heterogeneous streams. Complementary evaluations by van Hoorn et al. [

34] evaluated low-cost handheld devices (e.g., Plastic Scanner) revealed that hardware constraints—such as gaps between emission bands, low-power light-emitting diodes, and limited detector sensitivity—frequently lead to misclassification despite the use of advanced algorithms. Quantitatively, laboratory-grade NIR systems achieved accuracies of ~97% mid-range devices reached ~93%, whereas low-cost instruments showed substantially lower performance, ~70%.

These findings confirm that algorithmic sophistication cannot compensate for severe hardware limitations; ML can significantly enhance classification when spectral quality is moderate. Improvements in illumination bandwidth sources and improved detector sensitivity could therefore elevate portable NIR to industry-grade performance, making consolidating ML-enhanced NIR a cornerstone of accessible intelligent sorting systems in environments characterized by high material variability.

A critical intrinsic limitation of NIR-based sorting arises from the difficulty in distinguishing dark and black plastics that contain carbon black, one of the most widely used additives for imparting black or gray coloration. Carbon black exhibits strong absorption across the visible, ultraviolet, and near-infrared regions due to its extended conjugated graphitic structure, resulting in very low reflectance and feature-poor NIR spectra. As a consequence, black plastics are broadly recognized as particularly challenging—sometimes effectively unidentifiable—using conventional NIR approaches. While ML models applied to hyperspectral NIR datasets can extract subtle statistical patterns, classification performance for carbon black–containing plastics remains highly sensitive to data quality and experimental conditions, limiting robustness and generalizability in real-world waste streams [

37].

Beyond color effects, NIR performance can also deteriorate in thin films and highly transparent plastics, where reduced absorption contrast and a short optical path length yield weak or indistinct spectral features. These constraints highlight that NIR-based identification is fundamentally bounded by the physics of light–matter interaction, rather than solely by algorithmic capability. In this context, NIR is most effective when applied to relatively homogeneous, non-black plastic streams, while more complex or additive-rich residues may require complementary sensing strategies [

37,

38]. Taken together, these limitations underscore the need to integrate NIR within multi-sensor sorting architectures rather than relying on it as a standalone solution.

2.4. Raman Spectroscopy Supported by Preprocessing and AI Algorithms

Raman spectroscopy provides chemically specific vibrational fingerprints and is less affected by moisture or matrix complexity than NIR, making it a valuable tool for the heterogeneous or degraded plastics [

9]. Fang et al. [

7] evaluated three ML models—nearest neighbors, random forest, and artificial neural networks—trained on Raman spectra of standardized plastics. In their study, due to baseline drift and noise, fluorescence identification emerged as the principal challenge, leading to baseline drift and spectral noise that hindered the identification of polymers such as ABS, PET, POM, and PVA. However, preprocessing (smoothing, baseline correction, normalization) dramatically improved accuracy.

Among the evaluated algorithms, the nearest neighbors model delivered the best balance of accuracy and computational speed, achieving 100% accuracy in controlled tests with processing times of ~4 ms. Combining spectral peak areas with statistical descriptors further improved robustness. Collectively, these results demonstrate that AI-enabled Raman systems can deliver rapid, high-precision identification, supporting the allocation of plastics across mechanical, chemical, and upcycling loops [

7,

9,

39,

40].

Nevertheless, methodological studies have shown that although Raman microspectroscopy can provide information on fillers and pigments that is not always accessible by FTIR, exclusive reliance on Raman analysis may lead to misidentification in real samples, particularly for coated or paint-derived particles. Accordingly, combined Raman–FTIR workflows have been repeatedly proposed as complementary strategies to improve particle-level characterization. Moreover, while Raman offers substantial potential for automated analysis of microplastics directly on filter substrates, performance is strongly influenced by surface-associated biological contamination: fluorescence induced by biofilms or other organic residues can dominate the Raman signal and prevent particle identification if appropriate sample preparation is not applied, and robust automation further requires systems capable of ensuring optimal focus on each candidate particle [

37].

Raman measurements can be dominated by surface and near-surface layers in reflective configurations, potentially biasing identification toward coatings or the outer layer in multilayer laminates. Accordingly, confocal Raman depth profiling or cross-sectional mapping (when feasible), and/or complementary sensing (e.g., FTIR or elemental fingerprinting), are recommended for multilayer or coated plastics to reduce layer-driven misclassification.

2.5. LIBS: Elemental Fingerprinting and AI for Complex Waste Stream

Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) has gained prominence for sorting complex or contaminated plastics, particularly those from electrical and electronic waste, where flame retardants or inorganic fillers must be detected. LIBS generates microplasmas that emit atomic signatures, enabling rapid identification.

Das et al. [

24] analyzed 1800 LIBS spectra from six resin categories. They demonstrated that support vector machines and multilayer perceptron neural networks achieved 92–96% accuracy, reaching >98% under dynamic conditions simulating conveyor belt operation. LIBS combined with AI is especially effective where vibrational techniques fail due to overlapping molecular signatures or heavy additive content. Its robustness under variable color, texture, and composition makes it a strategic technology for the most complex sorting scenarios in circular systems. These advances remain strongly dependent on the availability of curated, representative spectral databases, which continue to constitute a critical bottleneck for large-scale deployment.

2.6. Emerging and Hybrid Modalities for Challenging Stream

Beyond conventional FTIR/NIR/Raman workflows, recently developed sensing approaches are increasingly being explored to address “hard cases” that routinely degrade sorting performance, including carbon-black plastics, highly transparent thin films, multilayer laminates, and streams with complex additive packages. In such cases, reliance on a single modality can be insufficient, as the limiting factor is often the underlying physics of signal generation (e.g., absorption and reflectance constraints) rather than algorithmic sophistication alone. Consequently, contemporary research and industrial pilots increasingly emphasize hybrid and multi-sensor architectures that combine complementary modalities and interpret them through AI-enabled sensor fusion [

41,

42].

A prominent direction is the use of mid-wave and long-wave infrared hyperspectral imaging (MWIR/LWIR-HSI) and other mid-infrared configurations, which can retain discriminative signatures for black plastics where VIS/NIR reflectance becomes feature-poor due to carbon black absorption. These approaches can be deployed as standalone classifiers or integrated with visible imaging, geometry cues, and probabilistic decision layers that quantify uncertainty and route ambiguous items toward secondary verification. In parallel, elemental and compositional fingerprinting (e.g., LIBS and related approaches) is increasingly viewed as essential for additive-rich streams (e.g., WEEE/ELV plastics, pigments, flame retardants), where polymer identification must be complemented with flags for halogens, fillers, and legacy additives to protect downstream processes and ensure compliance [

43].

Another emerging direction is to reduce dependence on spectroscopic inference by embedding information carriers into products and packaging. Digital watermarking concepts and machine-readable identifiers can enable item-level identification when physical signatures are weak or confounded, providing a pathway to high-confidence routing for complex packaging formats. While such approaches require broad adoption and governance, they align with traceability-driven circularity strategies and can be coupled with automated sorting lines [

44,

45].

Finally, when biological or enzymatic routes are considered—particularly for streams originating from agricultural applications—feedstock qualification should include screening for pesticide/agrochemical residues and other inhibitory contaminants, as these can suppress biocatalytic performance and complicate downstream purification. Overall, these emerging modalities reinforce that advanced sorting should be treated as a multi-modal decision layer that integrates polymer identity, additive/degradation indicators, and uncertainty-aware routing to match each stream to the most compatible valorization pathway [

46,

47].

2.7. Data Availability, Database Development, and Governance Challenges for AI-Based Plastic Identification

The performance of AI-based systems for plastic identification is critically constrained by the availability, quality, structure, and governance of the spectroscopic data used for model training and validation. Although recent advances in ML and deep learning (DL) have demonstrated strong potential to automate polymer classification, the literature consistently shows that these models remain highly dependent on the data context in which they are developed and evaluated, limiting their generalization and transferability to real recycling scenarios.

Traditional chemometric and conventional ML approaches have demonstrated adequate performance under controlled laboratory conditions but are typically trained on relatively small, highly curated datasets. In this context, Tian et al. [

48] demonstrated that classification performance is strongly influenced by dataset size, class imbalance, and spectral quality, showing that when datasets are small or imbalanced, even advanced models struggle to classify all polymer categories consistently. Importantly, these authors note that many published comparisons rely on datasets of fixed size, without systematically assessing how performance evolves as the number of samples changes—an important limitation given that real laboratory and industrial datasets are often constrained and heterogeneous.

From a complementary methodological perspective, Rosales-Martínez et al. [

49] showed that, under controlled experimental conditions and with high-quality spectral data, the combination of appropriate spectral preprocessing—particularly derivative-based transformations—with ML models can yield extremely high classification accuracy for common polymers using FTIR. However, the authors explicitly caution that these results must be interpreted within their experimental context, as they are obtained from relatively pure and well-characterized samples. They further note that model generalization may be compromised by polymer mixtures, degradation, additives, contamination, or instrumental variability, which are characteristic of real PC plastic waste streams.

More recently, Singh et al. [

50] demonstrated that advanced DL architectures, including Transformer-based models, can capture complex spectral patterns and outperform traditional chemometric and ML approaches across multiple spectroscopic datasets (FTIR, NIR, and hyperspectral NIR). Nevertheless, these authors emphasize that high performance is critically dependent on the availability of sufficiently large, diverse, and well-structured datasets, as well as on explicit control of data leakage and domain shift between experimental and industrial conditions. As a result, reported performances primarily reflect within-dataset generalization and do not guarantee direct transferability to unseen samples or operational sorting lines without additional adaptation strategies.

In addition to overall accuracy, AI-enabled sorting studies should report class-wise precision, recall, and F1-score (preferably macro-averaged), together with balanced accuracy and a confusion matrix, to avoid overstating performance in imbalanced datasets and to expose failure modes for “hard-case” streams (e.g., carbon-black plastics, thin transparent films, or additive-rich composites). Where probabilistic outputs are available, ROC–AUC/PR–AUC and calibration metrics can further support decision-threshold selection in safety- and compliance-relevant applications. Finally, reporting external validation (cross-site, cross-device, or temporally separated test sets) is recommended to quantify generalization under realistic distribution shifts and to ensure that gains observed in curated datasets translate into reliable performance in heterogeneous, real-world waste streams [

15,

51,

52].

Taken together, these studies indicate that the primary bottleneck for the reliable implementation of AI-based plastic identification systems lies not in algorithm selection or model architecture, but in the development of robust, representative, and well-governed spectroscopic databases. In practice, most datasets reported in the literature originate from academic settings, are generated under controlled conditions, and lack the diversity required to reflect the intrinsic variability of post-consumer plastic waste, including different aging states, formulations, additives, contaminants, and acquisition conditions.

Beyond data availability, data governance emerges as a central challenge. The lack of standardization in spectral acquisition protocols, preprocessing pipelines, class labeling schemes, and dataset partitioning strategies limits cross-study comparability and model reproducibility. Both Singh et al. and Tian et al. [

48,

50] stress the need for more rigorous validation strategies, including grouped or site-aware data splits, formal statistical testing, and explicit evaluation of how dataset size and composition affect model performance.

Overall, current progress in building databases for AI-based plastic identification remains at an early stage. While public datasets and isolated expansion efforts exist, the reviewed literature consistently points to the need for larger, more diverse datasets, along with governance frameworks that ensure data traceability, quality control, and interoperability. These elements are essential to move beyond laboratory-scale proof-of-concept studies toward robust automated classification systems capable of operating reliably in real industrial and recycling environments.

2.8. Limitations and Future Challenges in AI Applications

Despite rapid advances, AI-enabled sensing and sorting in circular plastic systems faces several limitations that constrain real-world deployment and comparability across studies. Data limitations remain central: spectral and imaging datasets are often small, curated, and device-specific, with incomplete representation of real waste variability (additives, fillers, aging, contamination, multilayers). This leads to domain shift between laboratory conditions and operational environments, where changes in illumination, particle geometry, moisture, biofilms, and throughput can degrade performance. Class imbalance and ambiguous labels (e.g., blends, coated materials, carbon-black plastics, thin films) further complicate training and evaluation, underscoring the need for standardized reporting beyond accuracy (precision/recall/F1, confusion matrices, external validation) [

41,

42,

43,

48,

49,

50].

Operational constraints also limit adoption. Many sensing modalities require trade-offs among speed, footprint, sample preparation, and cost; moreover, mis-sorts may propagate downstream, affecting recyclate quality and safety. Robust deployment therefore requires closed-loop monitoring, routine performance verification, and integration with process logic (reject handling, re-routing, and quality gates). For high-stakes streams (e.g., WEEE/ELV fractions with legacy additives), AI outputs must be aligned with compliance needs and supported by confirmatory analytics and traceability [

43,

44,

45].

Transparency and governance constitute additional challenges. Black-box models may be difficult to audit, and biased training data can systematically underperform on underrepresented waste fractions. To enable accountability, future work should prioritize interpretable models where feasible, clear confidence/decision thresholds tailored to application risk, and well-documented validation procedures. Shared benchmarks, open protocols, and harmonized metadata (polymer grade, additive/degradation fingerprints, device settings, environmental conditions) will be critical to improve reproducibility and transferability [

48,

50].

Looking forward, key opportunities include multi-sensor fusion (combining NIR/Raman/FTIR/LIBS with imaging) and traceability infrastructures (e.g., machine-readable identifiers/digital watermarking) that provide higher-quality upstream information. Finally, linking AI-enabled sorting with system-level decision support (LCA/TEA-informed routing) will be essential to ensure that performance gains translate into measurable circularity outcomes rather than local optimization [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

3. Optimization of Mechanical, Chemical, and Biological Recycling Routes

Optimizing recycling routes within circular plastic systems requires addressing degradation pathways, improving material performance retention, and managing feedstock heterogeneity, as these conditions ultimately determine process viability, yield quality, and circular value recovery. Under CE principles, plastics are reincorporated into multiple-use cycles through mechanical, chemical, or biological routes, each of which requires tailored optimization strategies to increase recovery efficiency, reduce energy consumption, and sustain material performance across repeated loops. These recycling pathways present distinct operational boundaries driven by degradation history, contamination level, and polymer compatibility [

29,

53]. However, all are increasingly strengthened by emerging tools such as predictive modeling, catalyst-informed process design, and advanced bioengineering strategies that improve decision-making during sorting, processing, and final allocation.

3.1. Optimization of Mechanical Recycling

Mechanical recycling remains the most widely adopted and industrially implemented strategy due to its simplicity, low capital expenditure, and compatibility with existing infrastructure [

3,

54]. However, its performance strongly depends on the polymer history, contamination level, and the degree of thermo-oxidative degradation accumulated over the service life [

21,

22].

Recent advances demonstrate that process optimization begins at the extrusion stage. Edeleva et al. [

53] report that control of residence time, screw configuration, melt rheology, and stabilizer dosing governs chain scission, crosslinking, and viscosity loss. When properly controlled, these variables improve the integrity of the recyclate and energy efficiency during extrusion.

Material compatibility is another key driver of optimization for mixed streams [

55]. Hassanian-Moghaddam et al. [

54] highlight that olefin-block compatibilizers, covalent-adaptable networks, and specific fillers expand the applicability of recycled polyolefins by improving interfacial adhesion. These stabilization strategies are especially relevant when transitioning from PI to heterogeneous PC flows. These approaches expand circularity thresholds for mixed polyolefin streams, often associated with packaging, automotive, and consumer goods waste [

3,

8].

Economically, mechanical recycling remains preferable when contamination is low and when feedstock quality supports high-value direct reuse. Uekert et al. [

56] report that mechanical recycling outperforms other closed-loop options when sorting quality is adequate, and degradation remains below mechanical-property critical limits. Their analysis further indicates that the transition to chemical pathways occurs when the recyclate quality falls below the reprocessing grade specifications.

From a circular-strategy standpoint, low-input-energy material recycling (i.e., mechanical reprocessing into regranulates) should preferentially target products with high substitution potential and modest performance sensitivity, such as rigid packaging and non-food-contact consumer goods, as well as durable items (e.g., crates/pallets and construction profiles/pipes) where minor property drift can be accommodated. Conversely, high-specification applications (e.g., strict food-contact uses) generally require more stringent decontamination, traceability, and property assurance; when these conditions are not met, chemical or biological routes may become more appropriate to restore functionality at the monomer/intermediate level.

Moreover, integrating real-time monitoring with predictive algorithms enables decision-making before irreversible degradation occurs. Inline FTIR/NIR analysis, melt-flow index tracking, and residency-time prediction models allow assigning materials to appropriate loops before quality losses accumulate—improving yield retention and energy efficiency. Overall, mechanical optimization converges on:

Minimizing thermo-mechanical degradation [

8];

Enhancing inter-polymer phase compatibility;

Minimization of mass losses along washing, melting, and filtration steps;

Integrating predictive extrusion-quality models.

3.2. Optimization of Chemical Recycling

Chemical routes—particularly pyrolysis, solvolysis, hydrogenolysis, and depolymerization—support recovery when waste is highly heterogeneous or degraded, making mechanical pathways unsuitable [

20]. Catalyst engineering and the integration of kinetic models are central to improving purity-product curves.

Huang et al. [

55] emphasize that process intensification through catalyst selection governs selectivity, hydrocarbon distribution, and coke formation. Catalyst–product relationships show that zeolites enhance aromatics, silica–alumina systems improve cracking balance, and fluid-catalytic designs accelerate conversion while reducing tar formation.

Life-cycle trade-offs relative to mechanical approaches have been quantified by Jeswani et al. [

57], who conclude that environmental competitiveness improves only when thermal integration and selective upgrading steps are incorporated.

From an industrial perspective, Kumagai et al. [

58] highlight three optimization priorities:

Catalyst robustness across mixed streams;

Reduction in energy intensity per ton converted;

Validation of lab kinetic performance at pilot-plant scales.

Data-guided pyrolysis optimization is emerging as the most transformative area. Paavani et al. [

58] and Tomme et al. [

59] show that ML frameworks accurately predict wax, gas, aromatics, and fuel fractions based on input composition. These datasets establish predictive routes to maximize monomer-grade output while minimizing operating conditions via automated search spaces. A significant advance in the optimization of AI-enable thermochemical pathways is the study by Cheng et al. [

60], which developed ML models to predict products from continuous non-catalytic pyrolysis of plastic waste accurately. To do this, they compiled a database derived from 93 experimental studies and evaluated four supervised algorithms: decision trees, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, and Gaussian processes. Its objective was to identify which variables allow the performance of solids, liquids, and gases to be predicted more accurately, as well as the specific compositions within each fraction. The results show that decision tree-based models far outperform the other approaches, achieving coefficients of determination greater than 0.99 for predicting waxes, aromatics, gasoline, light gases, and condensable fractions.

Collectively, optimization of chemical routes depends on:

Kinetic-parameter predictive models;

Catalyst recombination studies;

Integrated heat-exchange schemes;

Selective downstream purification.

3.3. Optimization of Biological Routes

Bacteria and fungi can fragment polymers under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, generating low-molecular-weight compounds that can be assimilated, integrated into native metabolic pathways, or further transformed into valuable products through metabolic engineering. These processes typically operate under mild conditions—near-ambient temperatures and neutral to moderately buffered pH—thereby reducing the energy requirements relative to thermochemical conversion routes [

61,

62]. Despite these advantages, the practical implementation of biological recycling remains limited mainly to polyester-based waste streams such as PET, due to inherent limitations in polymer accessibility and enzymatic specificity.

Enzymatic hydrolysis studies have demonstrated that PETases and MHETases can depolymerize PET into high-purity monomers, including terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol. However, high crystallinity and limited surface accessibility significantly constrain reaction kinetics, rendering depolymerization the rate-limiting step [

10]. Consequently, preprocessing steps—e.g., amorphization, mechanical grinding, surface oxidation, or solvent-assisted swelling—are often required to enhance enzyme–substrate interactions and improve overall conversion efficiency.

Chen et al. [

63] indicate that biologically driven valorization is most effective under hybrid schemes combining controlled oxidation followed by microbial conversion. An example is the study by Zhan et al. [

58], who demonstrated that polyethylene, one of the most recalcitrant polymers due to the stability of its C–C bonds, can be chemically oxidized to generate C4–C6 dicarboxylic acids. A metabolically redesigned Corynebacterium glutamicum subsequently assimilated these intermediates. Similarly, Uekert et al. [

56] further indicate that enzymatic conversion routes can become competitive when solvent volumes, wash-water demand, and enzyme loading are minimized through process integration and optimization.

Beyond polymer structure and pretreatment requirements, the feasibility of biological recycling routes is also conditioned by the chemical history of the waste stream. Recent studies have shown that polyethylene and polypropylene microplastics can adsorb a wide range of organic contaminants, including pesticides and pharmaceuticals, primarily through physical interactions such as van der Waals and electrostatic forces [

64]. Field-based evidence further indicates that aged plastic fragments collected from agricultural environments retain measurable pesticide residues after real-use exposure, with concentrations in the polymer matrix often exceeding those detected in surrounding soils [

65]. Taken together, these findings suggest that plastic materials used in agrochemical contexts may carry residual organic compounds beyond their service life. Such contamination not only constrains high-value upcycling applications but may also interfere with biological recycling routes, as residual agrochemicals can inhibit microbial metabolism or compromise enzymatic stability under the mild operating conditions required for biocatalytic conversion. Accordingly, biological valorization strategies require upstream screening and, where necessary, targeted decontamination steps to ensure compatibility between the waste stream and microbial or enzymatic systems.

A structural limitation nonetheless persists. In contrast to mechanical and chemical recycling, the optimization of biological routes is constrained by the limited availability of a curated enzymatic dataset, including:.

Comprehensive PETase and esterase mutational libraries,

Kinetic profiles spanning different crystallinity grades and polymer morphologies;

Systematic validation of ML-guided enzyme design workflows under industrially relevant conditions.

This data scarcity has historically slowed the translation of promising biocatalysts from laboratory discovery to scalable processes. Addressing this limitation, Jiang et al. [

66] developed PEZy-Miner, a ML computational framework designed to identify enzymes with plastic-degrading potential from large sets of uncharacterized protein sequences. The approach combines protein language models that encode implicit structural and functional features with supervised classifiers that predict degradative activity across 11 polymer types. By prioritizing high-confidence candidates and quantifying prediction uncertainty, PEZy-Miner enables more efficient experimental screening and accelerates the discovery of novel biocatalysts, thereby supporting the development of modular and scalable biological recycling platforms.

3.4. Cross-Route Optimization Perspective

Across loops, optimization is influenced by feedstock state, compatibility requirements, and targeted product quality thresholds:

Mechanical loops maximize value when polymer memory is known, and degradation is minimal.

Chemical loops maximize value when the waste stream is heterogeneous, multilayered, or contaminated.

Biological loops uniquely deliver monomer-grade purity but require substrate accessibility and bio-catalyst engineering.

At present, convergent industry trends emphasize integrating:

This provides decision frameworks where each stream feeds into the most favorable loop based on circular-value recovery rather than cost alone.

3.5. Integrative Resources: Comparative Table and Conceptual Diagram

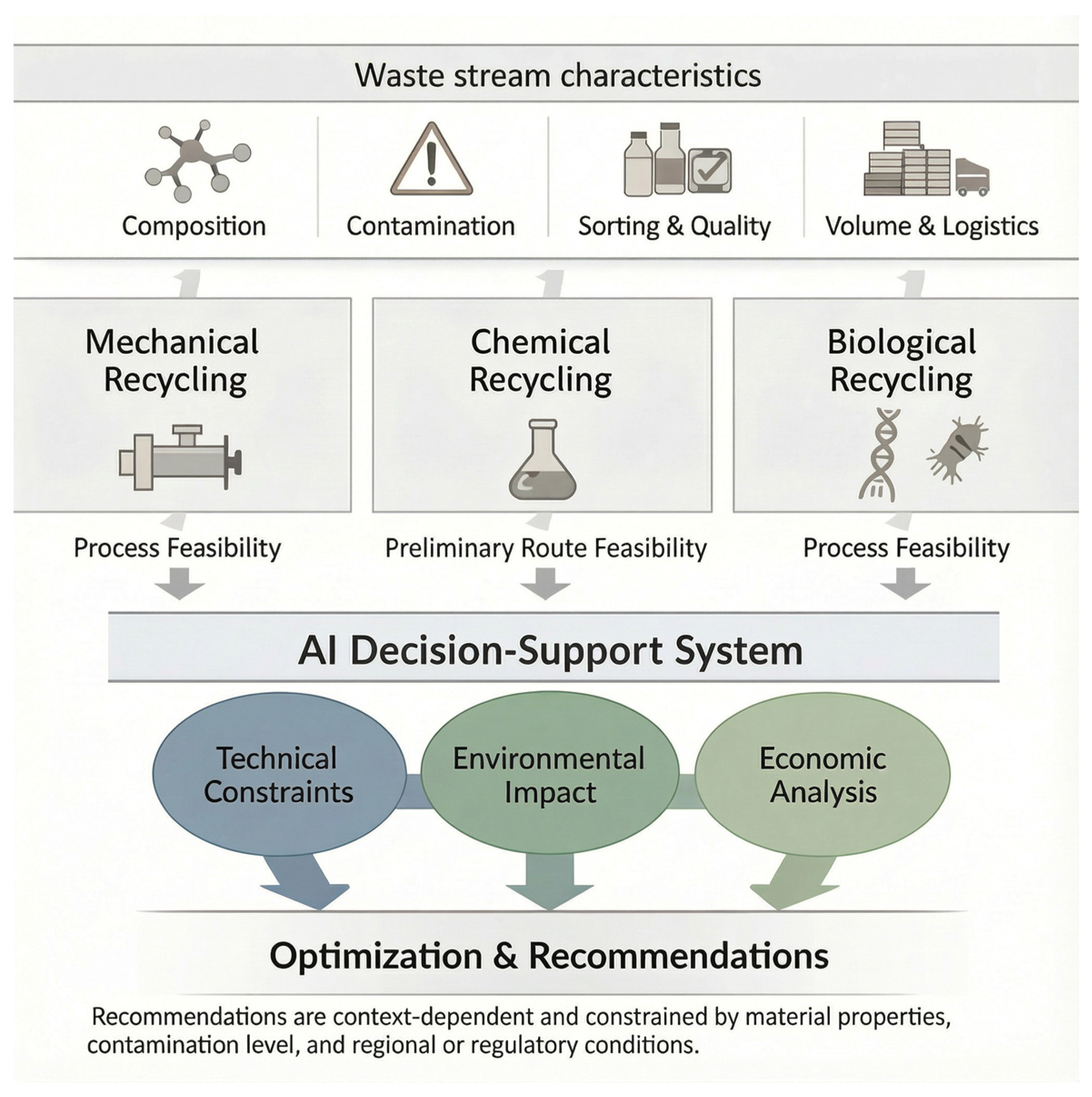

To elucidate the interactions among optimization pathways within circular systems,

Figure 2 presents a conceptual decision framework for allocating post-consumer and post-industrial plastics to mechanical, chemical, or biological recycling routes. Allocation criteria include material condition, processing constraints, and anticipated value retention. Complementarily,

Table 1 provides a structured comparative summary of technological levers, quantitative descriptors, and performance indicators documented in the recent literature, enabling systematic evaluation of optimization priorities.

Importantly, route selection is not predetermined; it is informed by predictive decision-support models that integrate material quality, environmental impacts, techno-economic assessments, and digitally enabled diagnostics. Mechanical recycling performance is primarily governed by melt stability and compatibilization strategies, whereas chemical pathways depend on catalyst selectivity, reactor configuration, and energy intensity. Biological routes emphasize enzymatic efficiency, polymer accessibility, and hybrid integration for monomer recovery. These indicators collectively support the classification and prioritization of processing routes within circular-economy decision frameworks.

4. Upcycling Pathways for High-Value Recycled Polymer Materials

Upcycling emerged as a counterproposal to traditional recycling practices and was widely introduced by Michael Braungart and William McDonough in Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things [

67,

68], where they proposed transforming discarded materials into products of higher added value through creative, ecologically oriented design [

15]. Unlike conventional recycling—where materials degrade progressively, and experience reduced mechanical or economic performance after successive cycles—upcycling introduces the opposite logic: transforming waste into products with superior functional, aesthetic, or economic attributes [

69].

This paradigm aligns with the principles of the CE by integrating design strategies that anticipate multiple life cycles, minimize waste from the outset, and encourage modularity and reusability. As a result, upcycling reduces energy consumption, prevents premature disposal, enables the creation of unique high-quality products, and fosters innovation from the design stage [

70].

When applied to plastic waste, upcycling offers pathways to recover high-value molecules, functional materials, and specialized products that often outperform conventional polymer resins. While traditional recycling—particularly for post-consumer plastics—faces challenges such as contamination, structural degradation, and water-intensive cleaning stages [

71], upcycling leverages chemical, thermal, electrochemical, biological, or hybrid conversion routes to transform carbon-rich residues into valuable resources rather than simply diverting them from landfill.

4.1. Technical Pathways for Plastic Upcycling

4.1.1. Chemical Routes

These involve depolymerization or selective bond cleavage, including glycolysis, solvolysis, hydrolysis, alcoholysis, aminolysis, oxidation, and hydrogenolysis [

41]. Polyester-based plastics (e.g., PET, PLA) exhibit high selectivity toward monomers such as terephthalic acid, dimethyl terephthalate, or ethylene glycol [

72].

4.1.2. Thermal and Thermochemical Process

Research on pyrolysis and gasification of plastics has emerged as a critical area of inquiry due to the escalating environmental challenges posed by plastic waste accumulation and the urgent need for a sustainable energy recovery method. Pyrolysis, which involves the thermal decomposition of plastics in the absence of oxygen to produce high-purity fuels and monomers, is a practical approach [

73]. Since the early 2000s, thermochemical conversion technologies have evolved from conventional pyrolysis to advanced catalytic and microwave-assisted processes, enhancing energy efficiency and product selectivity. This versatile method converts plastics into gas by partial oxidation at temperatures above 800 °C, producing fuels or chemicals [

63,

74]. Despite advances, the efficient valorization of plastic waste through pyrolysis and gasification remains challenging, particularly in optimizing catalysts, reducing energy consumption, and ensuring product quality [

75].

4.1.3. Electrochemical Upgrading

Research on the electrochemical upgrading of PET and PLA derivatives has emerged as a critical area of inquiry, with the potential to address plastic pollution while producing valuable chemicals and green hydrogen. The field has evolved from initial studies on PET hydrolysate oxidation to advanced catalyst designs enabling industrial-scale current densities and high selectivity for products such as formate, glycolate, and hydrogen [

76,

77,

78]. Despite progress, challenges remain in achieving efficient, selective, and economically viable electrochemical conversion of PET and PLA derivatives. Key knowledge gaps include developing cost-effective catalysts with high activity and stability at industrially relevant current densities, understanding the mechanistic pathways of selective oxidation, and optimizing process efficiency for simultaneous hydrogen production [

77,

79].

4.1.4. Biological Upcycling

Research on the enzymatic degradation of plastics by cutinases, lipases, and carboxylesterases has emerged as a key subject of investigation due to the escalating environmental impact of plastic waste accumulation and the limitations of conventional recycling methods [

80,

81]. Since the 1990s, advances in understanding microbial and enzymatic degradation mechanisms have evolved, with early studies focusing on natural polymer degradation and recent efforts targeting synthetic polymers such as PET and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) [

81,

82].

Despite progress, enzymatic degradation of plastics faces critical challenges, including low catalytic efficiency on highly crystalline polymers, enzyme instability under industrial conditions, and limited understanding of the roles of microbial consortia in plastic upcycling. While cutinases and lipases have demonstrated activity against various polyesters, their performance on persistent plastics such as polyethylene and polypropylene remains [

80,

81,

82,

83].

4.1.5. Polymer Blending and Compatibilization

Mixed plastic waste typically includes a variety of polymers, such as PE, PP, PS, and PET. These materials are often recycled from uncleaned, unsorted waste, leading to a heterogeneous mixture that complicates recycling efforts. The inherent incompatibility among these polymers results in poor mechanical properties and phase segregation when they are blended without a compatibilizer [

57]; the introduction of compatibilizers, such as organic esters, acids, or modified polymers, is needed to improve the mechanical properties [

10,

83,

84,

85]. Plastic waste can be utilized in construction materials, such as concrete mixtures and block manufacturing, to produce durable, heat-resistant, and water-resistant products. The combination of plastic waste with solid waste materials such as furnace slag and fly ash can produce composite building materials that are non-toxic, odorless, and recyclable, aligning with the clean production principle [

86].

4.2. AI as an Optimization Driver in Upcycling

Due to the high variability of plastic waste, process uncertainties, and nonlinear conversion mechanisms, upcycling systems benefit significantly from AI-enabled optimization,

Table 2. ML supports predictive modeling, material discovery, and reactor-level control, helping overcome processing inefficiencies. Means et al. [

87] conducted a large-scale data mining analysis of more than 10,000 published works, using natural-language processing to classify technological evolution trends. The analysis revealed that polyethylene and polypropylene are the most studied targets, that pyrolysis-based valorization is the dominant route, and that ML model integration is increasing for prediction and optimization.

Li et al. [

89] analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the proliferation of medical plastic waste. They proposed four axes for the upcycling of plastic waste: (a) increase the biodegradability of materials; (b) transform plastics into high-value products through chemical processes; (c) promote closed recycling with biodegradation; (d) link renewable energies.

It was highlighted that AI can be integrated into catalyst design and the optimization of chemical processes, especially for predicting reaction selectivity and efficiency [

90]. However, these are conceptual proposals rather than experimental applications.

The upcycling of recycled plastics, combined with residual biomass derived from agro-industrial waste, enables the production of sustainable polymers and compounds with mechanical properties comparable to, and in some cases superior to, those of virgin materials. For them, it is necessary to use AI tools that allow the optimization of 3D printing parameters, as well as the incorporation of additives—compatibilizers, stabilizers, surface modifiers, etc.—to improve mechanical strength, thermal stability, and adhesiveness, while reducing dependence on virgin materials; opening new possibilities for the creation of innovative and sustainable materials [

91].

Qian and Ren [

92] reviewed thermal and thermochemical upcycling technologies, including incineration, gasification, and pyrolysis, and complemented them with process optimization methodologies. The authors highlight the use of tools such as experimental design, superstructure optimization, and green supply chain management, emphasizing that AI tools and computational models, such as neural networks and vector support machines, are essential for evaluating and optimizing conversion routes of plastics into high-value products. However, they are still in stages of conceptual integration.

Khairul Anuar et al. [

93] reviewed advances in recycling and upcycling of hazardous plastics, including mechanical, chemical, and biological methods. These authors highlight innovations such as enzymatic depolymerization of PET, conversion of plastic waste into carbon nanomaterials (graphene and nanotubes), and photocatalytic processes [

90]. Although they recognize limitations in scalability and economic viability, they point out that AI and ML are emerging as support tools for waste classification and the optimization of chemical processes, opening the way to overcome technical and regulatory barriers in the sustainable management of plastics.

In summary, AI tools can be used to optimize, predict, and design chemical, photocatalytic, biological, and simulation processes for the upcycling of plastics, enabling the recovery of high-value-added materials and the development of new materials with novel properties in the transition towards a CE of plastics.

4.3. Emerging Technological and Research Trajectories

Emerging technological trajectories in plastic upcycling increasingly position AI as an enabling tool for optimizing system performance and scaling industrial deployment. AI contributes to multi-objective optimization—considering yield, purity, carbon conversion, and selectivity—while improving reactor control, predictive maintenance, and data-driven decision-making. In parallel, advanced computational tools, such as protein language models, are accelerating bio-pathway discovery, particularly in enzyme identification and metabolic engineering for polymer depolymerization [

94]. Hybrid simulations combining computational fluid dynamics and ML frameworks further support process intensification under realistic industrial constraints.

Beyond purely technological advances, research is shifting toward integrating upcycled plastics with agro-industrial byproducts to produce composite biopolymers with superior properties. This direction is reinforced through AI-enabled optimization of 3D-printing parameters, simulation-driven additive selection, automated prediction of stabilizer and compatibilizer performance, and mechanochemical modeling to estimate long-term durability. As emphasized by Qian & Ren [

95] and Khairul Anuar et al. [

93], AI-guided optimization remains fundamental for scaling both thermochemical and biological upcycling systems to viable industrial levels, particularly in contexts where techno-economic viability, process reproducibility, and regulatory requirements still present significant challenges.

Upcycling provides value-positive material circularity by transforming post-consumer plastics into monomers, carbon-rich nanomaterials, high-performance composites, and functional biochemicals. AI-enabled strategies accelerate process efficiency, enhance selectivity, and guide new-material discovery, creating a technological pathway toward viable, scalable, high-value circularity.

This combination of design thinking, catalytic innovation, hybrid conversion routes, and AI-enabled decision systems positions upcycling as a cornerstone for the future of circular plastic systems.

4.4. Waste Biomaterials and Biochar as Functional Co-Feedstocks in Plastic Upcycling

Upcycling strategies can be strengthened by incorporating waste biomaterials—particularly plant residues (e.g., bagasse, rice husk, wheat straw, corn stover, fruit/vegetable pomaces) and animal-derived wastes (e.g., poultry feathers/keratin, crustacean shells as chitin/chitosan precursors, eggshell-derived CaCO

3, and manure-derived solids)—as low-cost, regionally available co-feedstocks [

96]. In practice, these streams can be used as (i) lignocellulosic fibers/flours to reinforce recycled polyolefins and PET, (ii) bio-derived functional additives (e.g., chitosan-based phases), or (iii) mineral/biogenic fillers (e.g., eggshell CaCO

3) that improve stiffness and dimensional stability in non-critical components. A particularly promising derivative is biochar, obtained via pyrolysis/thermoconversion of plant or animal wastes, which provides a carbon-rich, porous, and thermally stable filler. When properly milled and dispersed, biochar can contribute to mechanical reinforcement, UV/thermal stabilization, and (in some formulations) improved barrier or electrical properties, enabling upgraded products such as construction profiles/panels, decking, pallets/crates, and other durable applications [

97,

98].

However, waste-biomaterial-based upcycling requires explicit control of variability, moisture affinity, interfacial adhesion, and contaminant profiles. Effective implementation typically involves pretreatments (drying, sieving, de-ashing), compatibilization/coupling (e.g., maleated polyolefins for PE/PP), and quality assurance to mitigate odor, leaching risks (metals/PAHs), and property drift. Accordingly, these hybrid routes should be evaluated with standardized mechanical testing and application-relevant safety/regulatory screening to ensure that performance gains are achieved without shifting burdens downstream [

99,

100,

101].

4.5. Feasibility Gates for Upcycling: Thermodynamics/Energy, Catalysts, and Techno-Economics

Upcycling is often presented as a route to increase circular value beyond conventional recycling; however, its feasibility depends on three coupled “gates” that must be satisfied in practice: (i) thermodynamics/energy; (ii) catalysts and feedstock tolerance; (iii) techno-economics at scale.

Energy and thermodynamic constraints (Gate 1) are central for thermochemical upcycling (e.g., catalytic pyrolysis, hydrocracking, gasification), where high temperatures and heat duty can dominate the overall environmental and economic performance. Feasible deployment, therefore, relies on heat integration, energy recovery, and targeting products toward higher-value slates (chemicals/monomers) rather than fuel-only outputs, particularly when feedstocks are heterogeneous.

Catalyst constraints (Gate 2) frequently determine operational robustness. Real waste plastics contain additives, fillers, pigments, and halogenated fractions that can promote coking, poison active sites, and shift selectivity. Hence, catalyst design must be assessed alongside deactivation/regeneration behavior, tolerance to chlorine/metals, and the need for pre-sorting/decontamination. The sensitivity of yields and product distributions to operating conditions and blended waste inputs is illustrated by co-thermochemical processing studies [

22], reinforcing that “one-size-fits-all” upcycling is rarely realistic without feedstock conditioning.

Economic constraints (Gate 3) extend beyond reactor performance: the dominant cost drivers often include collection and pre-treatment, sorting/washing, removal of problematic fractions (e.g., PVC), catalyst makeup and lifetime, CAPEX for upgrading/separation, and compliance with emissions constraints. Recent TEA/LCA studies show that profitability and climate benefits are highly scenario-dependent and are strongly affected by the value of the product slate, energy prices, and plant integration.

Taken together, these gates indicate that upcycling is most feasible when (a) feedstock quality is controlled (via advanced sensing/sorting), (b) catalysts and separations are matched to contamination and degradation states, and (c) the targeted outputs provide sufficient value to justify the additional energy and processing requirements. This feasibility framing also clarifies why AI-enabled sensing and route selection are critical enablers for implementing upcycling under real-world constraints.

5. Life Cycle Assessment and Environmental Metrics in Circular Plastic Systems

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a fundamental analytical tool for evaluating the environmental burdens associated with plastics throughout their life cycles. Its methodological foundations evolved from early Resource and Environmental Profile Analyses (REPA) during the 1960s–70s [

102], originally applied to compare beverage packaging alternatives, leading eventually to the standardized framework established during the 1990s [

103,

104], defining requirements for goal definition, functional units, system boundaries, inventory compilation, and impact interpretation [

103,

104,

105]. These standards formalized requirements for system boundaries, functional units, life-cycle inventory development, and impact interpretation, enabling methodological transparency across material systems.

In the context of plastics, LCA has gained prominence due to increased attention to emissions from petrochemical-origin polymers, landfill persistence, and microplastic generation [

103]. Mechanical recycling often yields favorable environmental outcomes and lower global warming potential (GWP) than virgin polymer production. However, its effectiveness is constrained by feedstock heterogeneity, accumulated degradation, loss of mechanical performance, and contamination effects [

104]. In contrast, chemical recycling—especially pyrolysis and depolymerization pathways—enables monomer-level recovery and higher substitution equivalence but typically exhibits greater energy demands and process-related emissions, which vary significantly depending on reactor configuration and energy source [

105]. Emerging enzymatic and biological depolymerization pathways provide monomers of high purity, although current energy limitations and uncertain industrial scalability introduce environmental trade-offs [

106]. Upcycling systems, exceptionally when engineered for enhanced performance and extended product lifetime, can yield environmental gains, provided that substituted virgin materials are explicitly accounted for [

107].

5.1. System Boundaries Relevant to Plastic Circularity

The environmental interpretation of recovery routes depends heavily on the selection of system boundaries. The classification most commonly applied in plastics LCA literature includes Cradle-to-Gate, Gate-to-Gate, Cradle-to-Grave, and Cradle-to-Cradle boundaries [

108]. These boundaries determine whether environmental burdens will be attributed only to conversion stages or also to storage, use phase, and subsequent end-of-life pathways.

For complex circular scenarios, boundary selection must explicitly represent (i) multi-cycle loops with progressive property loss (“spirality”); (ii) open-loop cascade/downcycling where the recycled material serves a different function than the virgin benchmark; (iii) cross-regional transport and processing, which can dominate impacts through logistics and regional energy mixes. Multi-cycle modeling should state the number of loops considered, the quality-retention assumption (e.g., a quality factor or property-based discount), and the allocation/substitution rule used to credit displaced virgin production. For open-loop/downcycling, the functional unit should reflect the new application and the substitution ratio should be justified (often <1:1). For cross-regional systems, boundaries should explicitly include collection, baling, shipping, sorting, and reprocessing distances and should regionalize electricity/heat and end-of-life practices to avoid misleading comparisons across geographies.

A comparative summary is presented in

Table 3 to facilitate alignment among the recovery process type, the intended system scope, and the methodological rationale.

5.2. Performance Characterization of Chemical Recycling Routes

Chemical valorization routes—such as catalytic pyrolysis, glycolysis, methanolysis, alcoholysis, and oxidative fragmentation—restore polymer-derived carbon into usable precursor molecules. LCA outcomes demonstrate that the environmental benefits of chemical recycling depend strongly on conversion yield, energy source, solvent recirculation rates, catalyst life, and product recovery efficiency [

105]. Under fossil-derived heating, thermochemical conversion may exceed the energy demand of mechanical recycling; however, when powered by electrified low-carbon energy systems, monomer-grade outputs exceed the virgin displacement threshold and yield net GWP reductions [

105,

106].

5.3. Life-Cycle Implications of Upcycling Processes

Upcycling enables the recovery of value-enhanced outputs, such as nanocomposites, compatibilized blends, high-performance carbonaceous materials, and additive-modified formulations, yielding products that outperform the original resins [

107]. Unlike classical recycling, which typically reduces mechanical performance and polymer chain integrity over time, upcycling extends the life cycle and delays disposal. LCA comparisons show that when performance equivalence with high-grade virgin resin is achieved, avoided burdens outweigh additional material additions; however, the evaluation must quantify emissions associated with compatibilizers, catalyst synthesis, and dispersive processing.

5.4. Digital-Twin-Based LCAs and Computational Attribution

Recent studies incorporate digital twin models in LCA frameworks to simulate reactor thermodynamics, conversion yield distributions, degradation kinetics, and catalyst regeneration cycles [

105]. These models reduce allocation uncertainty by incorporating real-time process data. Simulation-assisted LCAs have quantified up to 25% variation in unit energy impacts depending on residence time and waste-composition fluctuation scenarios, strengthening scenario-based environmental predictions linked to industrial adoption readiness.

5.5. Comparative Findings Across Recycling Pathways

Cross-method assessment indicates that no individual technological pathway offers uniform environmental superiority. Mechanical recycling has the lowest energy intensity but suffers from quality attrition when input contamination exceeds thresholds [

104]. Chemical recycling achieves the highest monomer purity and closed-loop value recovery but involves energy-intensive stages whose net benefit materializes only under adequate purification and solvent recovery conditions [

105]. Biological depolymerization offers maximal theoretical circularity by producing monomers equivalent to virgin stock with minimal toxins [

106]; however, maturity and processing yield limitations remain. Upcycling, when linked to demonstrable substitution of engineering-grade resins, appears promising in long-horizon LCA scenarios [

107]. Instead, systemic decisions must be informed by environmental metrics derived from robust LCA approaches. Across technologies, environmental trade-offs arise from differences in energy demand, process intensification, additive impacts, and the substitutability of recycled materials. For instance, although mechanical recycling provides significant reductions in energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions relative to virgin resin [

104], its benefits diminish rapidly when feedstock heterogeneity, contamination, or polymer degradation degrades material quality. Conversely, chemical routes—particularly pyrolysis and depolymerization—enable high-purity outputs and valorization of complex waste streams, but they involve thermal hotspots that increase energy burden and emissions unless improved energy integration and catalytic optimization are implemented [

105]. Recent studies report that closed-loop depolymerization routes can match virgin performance from a functional perspective; however, their environmental profiles depend on the energy sources and conversion efficiencies used [

60,

112].

Bioconversion-based routes have emerged as highly promising pathways, particularly for PET, where enzymatic depolymerization produces monomers with minimal compositional variability. In LCA scenarios, biocatalytic depolymerization shows potential to outperform chemical pyrolysis due to lower thermal requirements and higher molecular circularity, provided that conversion rates, retention yields, and enzyme stability are optimized [

113]. Nonetheless, uncertainty persists, as large-scale enzyme production introduces environmental burdens associated with nutrient media, purification, and temperature control—requirements often overlooked in conventional impact models [

114]. In this context, policy frameworks must facilitate industrial deployment by accounting for upstream burdens and incentivizing stable energy integration, renewable-based heating, and local valorization cycles.

Upcycling represents a differentiated scenario. While material quality frequently surpasses that of standard recyclate, environmental burdens depend on additives, nanofillers, compatibilizers, and stabilizers, whose production may have non-negligible impacts [

107]. Studies integrating consequential LCA trends indicate that upcycling is justified when it demonstrably prevents production of energy-intensive virgin substitutes, particularly in packaging, electronics, engineered parts, and hybrid biodegradable composites [

87,

95]. Under such conditions, substitutability factors improve significantly, allowing circular materials to displace virgin grades at ratios of 0.8–1.0 based on mechanical properties, processability, and durability [

115]. This makes upcycling strategically relevant for countries with limited high-quality sorting infrastructure, since value addition compensates for feedstock limitations.

From a policy standpoint, regulatory instruments must integrate environmental metrics, technological maturity, and evidence of substitutability. EPR schemes have demonstrated measurable improvements in recovery rates when linked to material quality requirements and LCA-based incentives [

108]. However, EPR remains insufficient without digital traceability that can attribute environmental burdens to specific waste sources. Recent frameworks incorporating blockchain-based material passports and AI-based sorting quality indices indicate that traceability correlates with improved recyclate consistency, reduced rejection fractions, and decreased transport-induced emissions [

87].

International guidelines also recommend adopting harmonized functional units that reflect real service performance rather than simple mass equivalence (ISO 14040; ISO 14044) [

103,

104]. Studies comparing one kg-gate outputs of recycled resin display bias when downstream performance differs substantially, especially under mechanical degradation or quality downgrading. Alternative functional units—such as equivalent protection time in packaging, mechanical strength-adjusted kilogram equivalents, or normalized service lifetime—yield clearer environmental profiles [