Using Biopolymers to Control Hydraulic Degradation of Natural Expansive-Clay Liners Due to Fines Migration: Long-Term Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

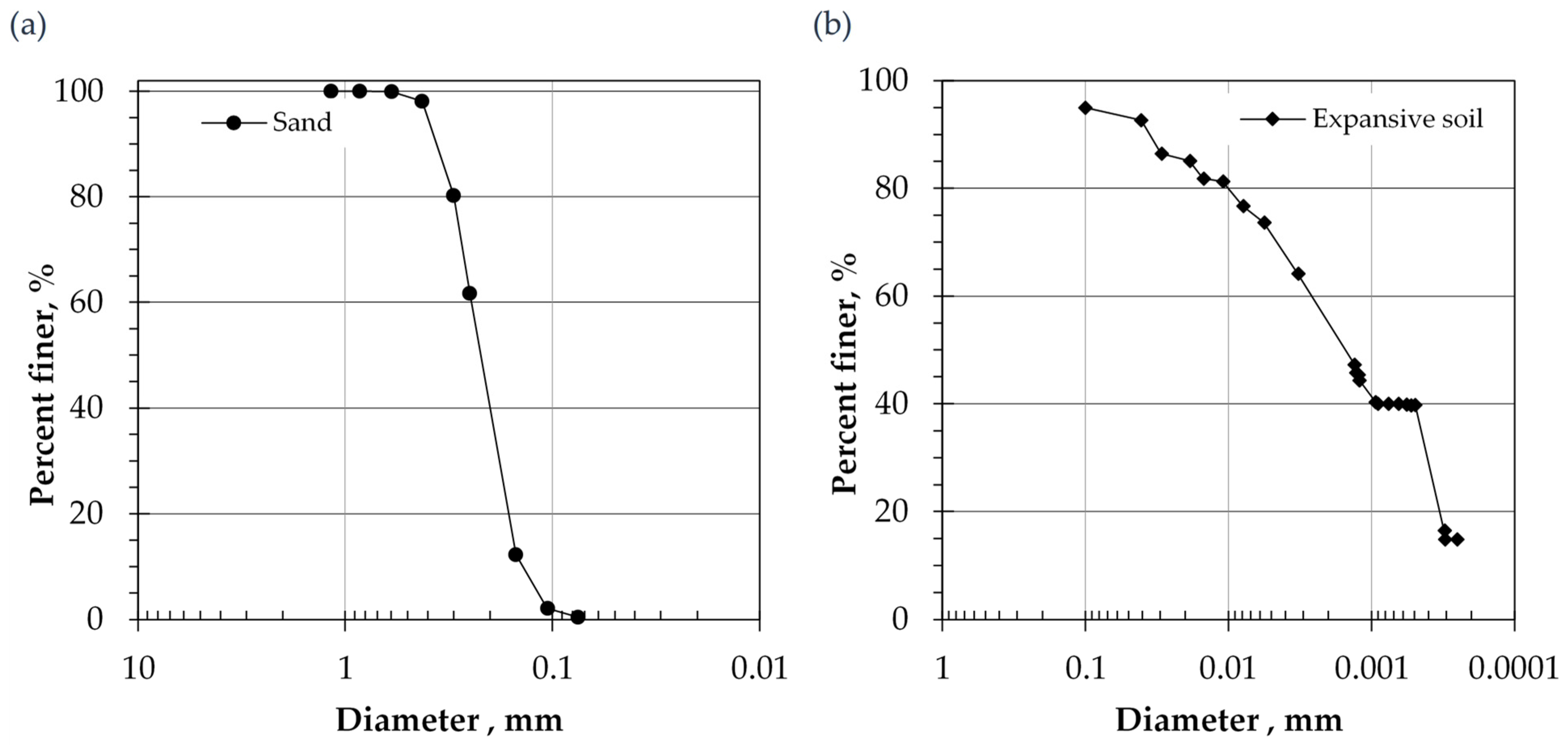

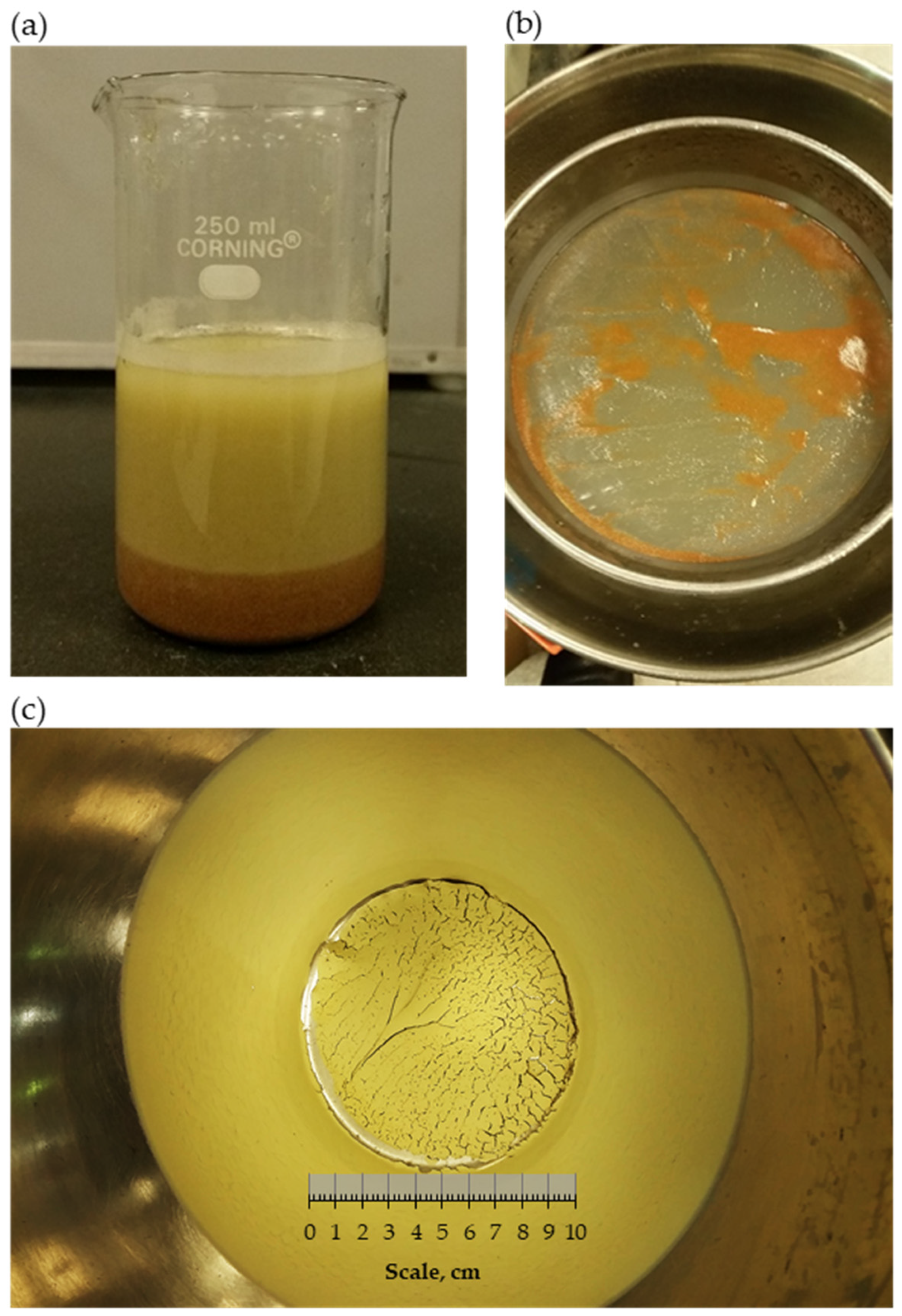

2. Materials and Methods

3. Mixtures and Specimens Preparation

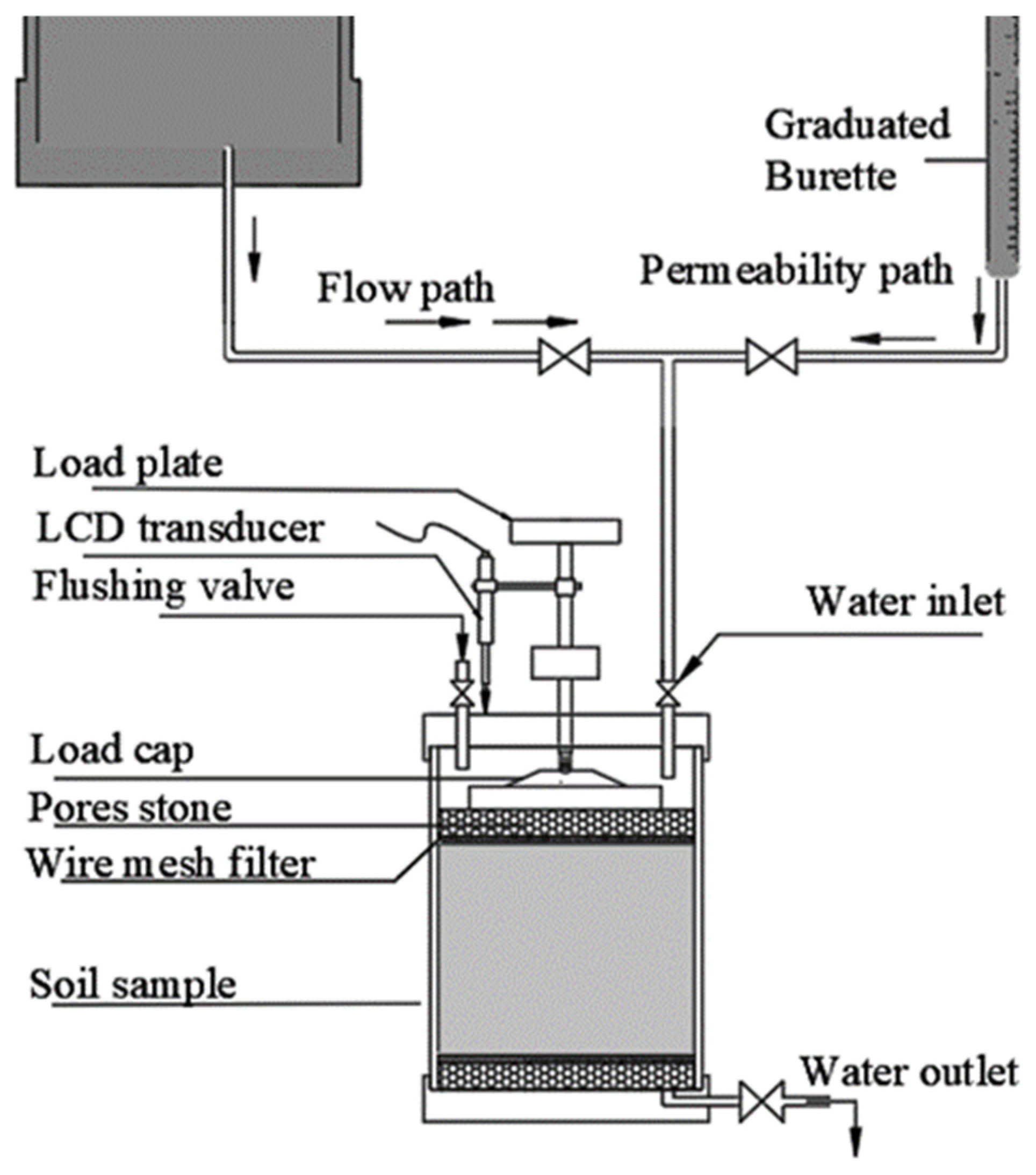

4. Testing Procedures

5. Results and Discussion

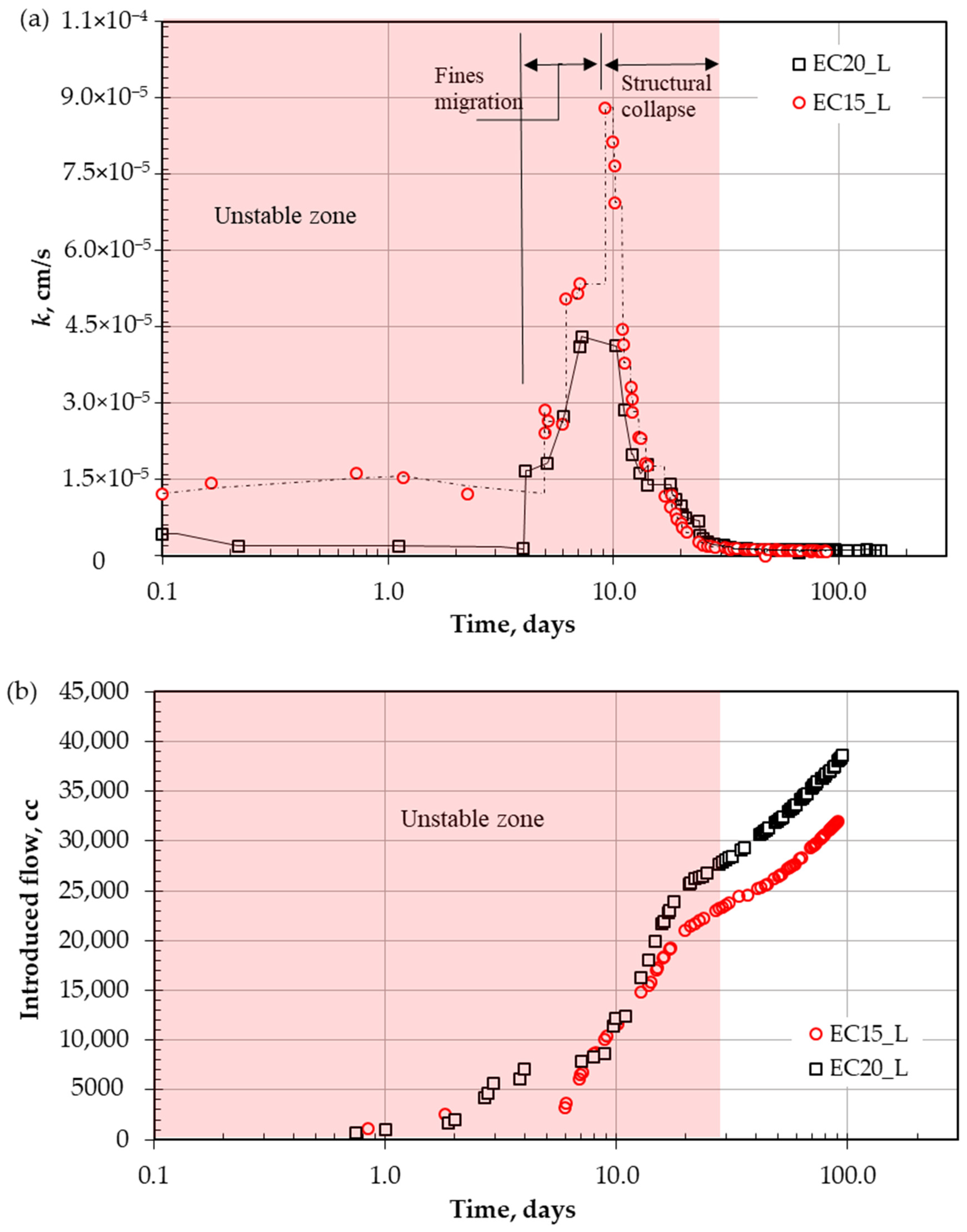

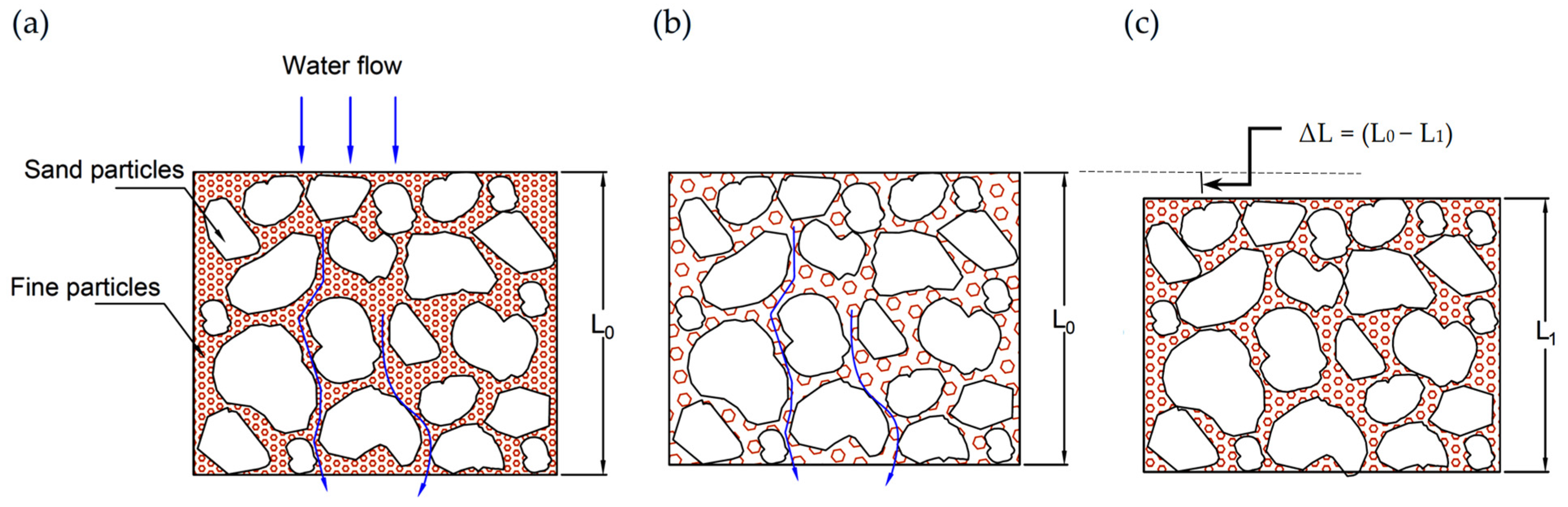

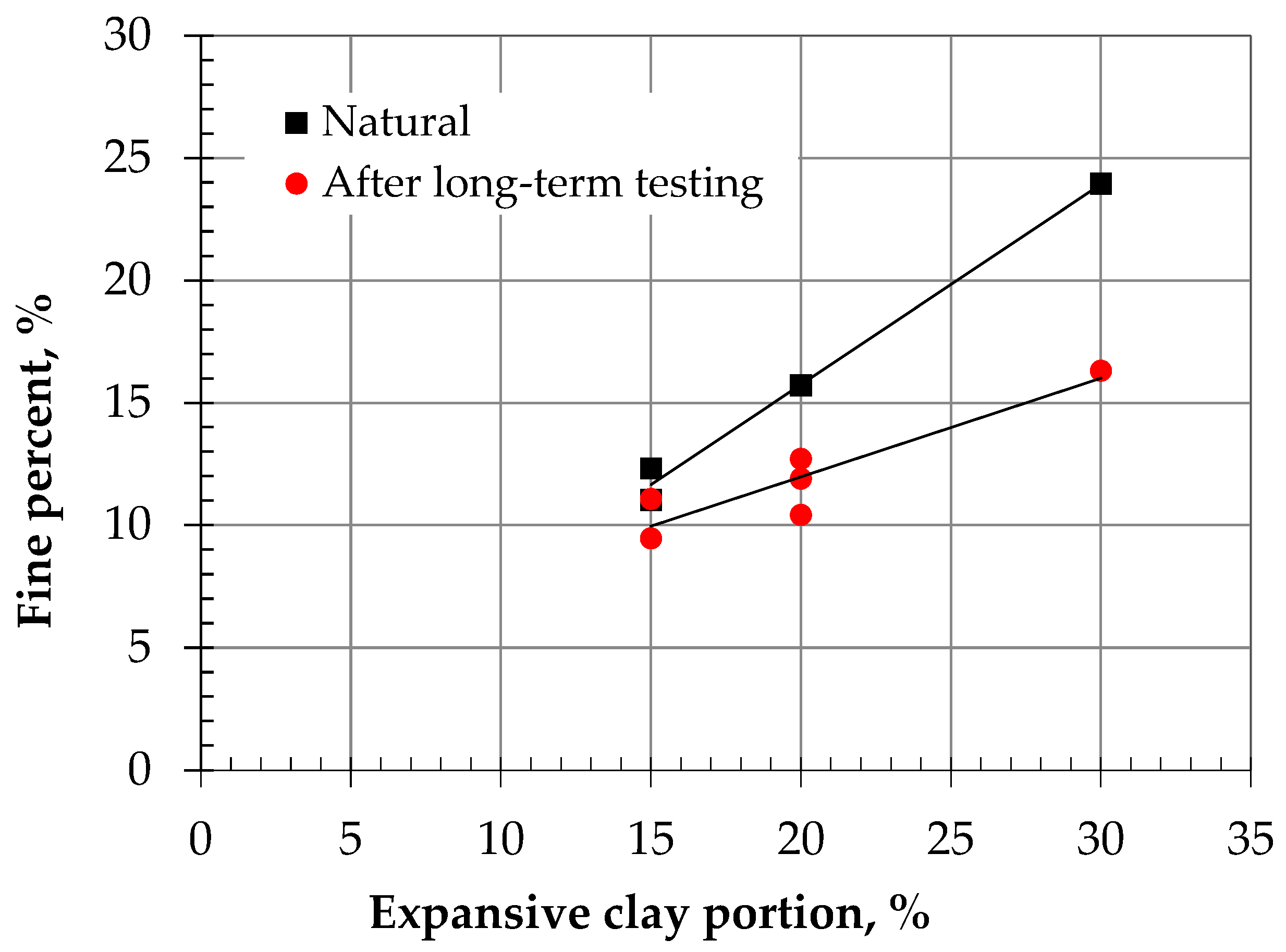

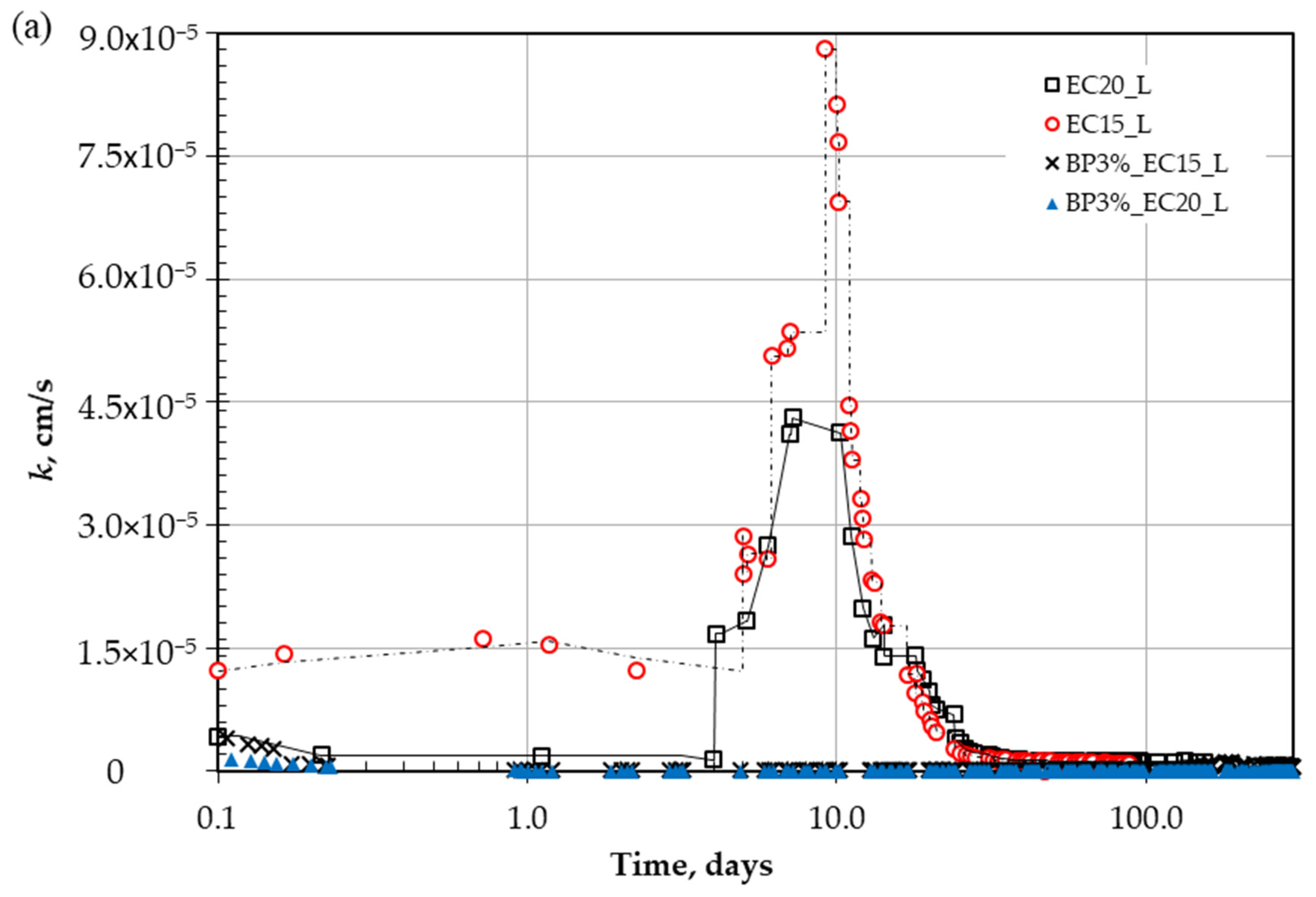

5.1. Degradation of the Liner’s Efficiency over Time

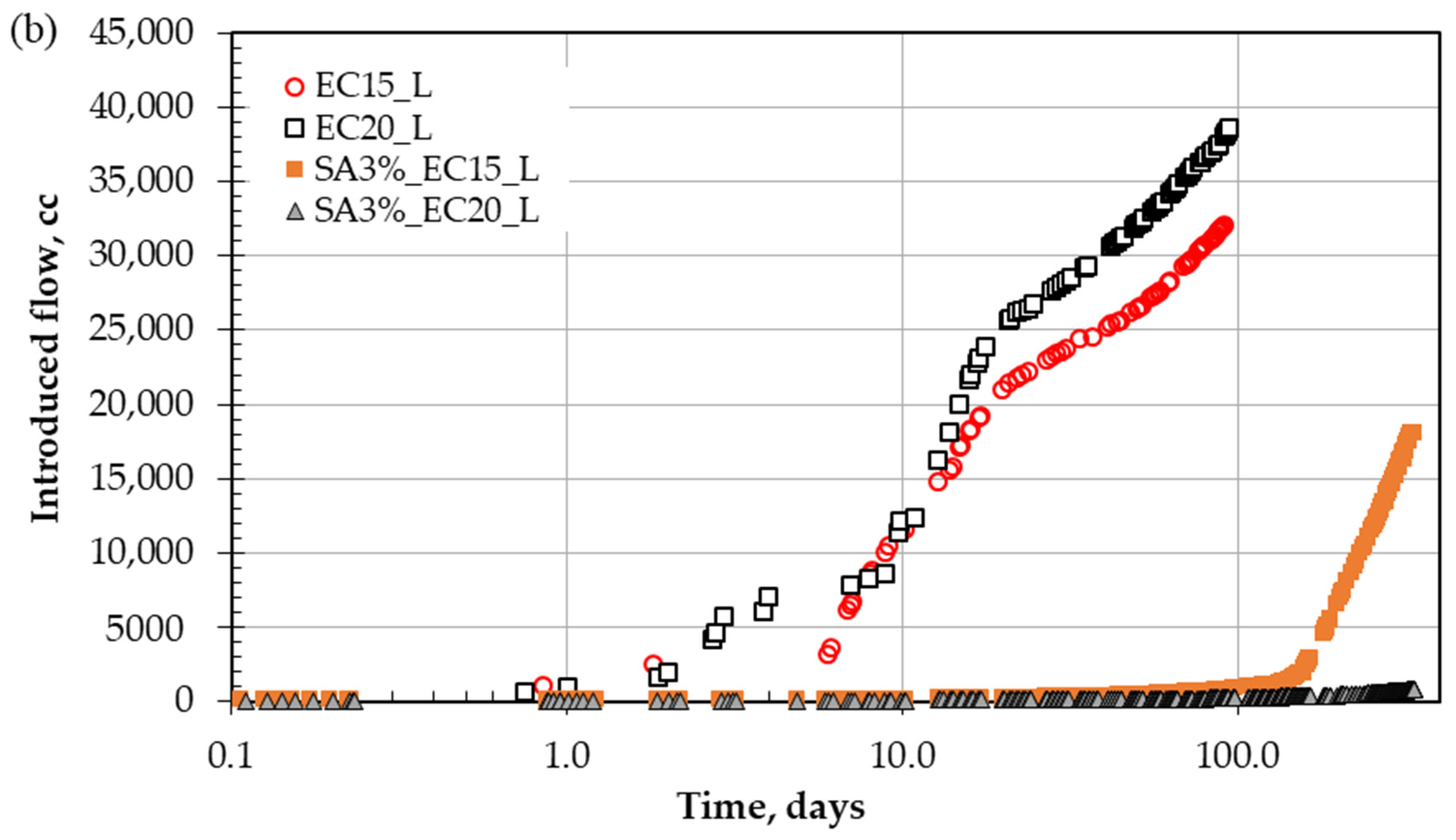

5.2. Effect of Biopolymer on the Long-Term Performance of Tested Liners

5.3. Comparing the Effect of Biopolymer Type on Long-Term Performance

6. Summary and Conclusions

- The hydraulic conductivity of the examined expansive clay liners undergoes extreme degradation under continuous flow, and an unstable zone was extended over the first forty days.

- The degradation of hydraulic conductivity is attributed to the migration of fine particles; the measured percent loss of fines varied from 16% to 32% and showed an ascending trend with the increase in expansive clay portions.

- Fine migration leads to a sharp peak permeability increase exceeding six times the initial value within the first ten days; subsequently, the weakened structure collapses, which enables particles rearrangement and a recovery of hydraulic conductivity to a stable performance level after forty days.

- Incorporating a 3% biopolymer (SA and GG) significantly enhanced the long-term stability of the hydraulic conductivity for both EC150 and EC20 liners. Unlike untreated ones, the biopolymer-treated liners maintained a stable trend over an extended one-year testing period.

- Specifically, polysaccharide biopolymers used in this study stabilize soil by binding particles together through physical, chemical, and microstructural mechanisms. The formation of advanced composite films or hydrogels significantly enhances particles bonding and improves overall stability.

- EC20 liner treated with 3% SA showed the most stable performance. Microstructural analysis confirms biopolymer gel films coat particles, creating a stable matrix and minimizing fine particle migration, and a 3% SA concentration is sufficient for stable hydraulic performance in EC20 liners, while low expansive clay content minimizes drying cracks and volume changes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouazza, A. Geosynthetic clay liners. Geotext. Geomembr. 2002, 20, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlin, B.; von Maubeuge, K. Geosynthetic clay liners (GCLs). In Proceedings of the 4th International Pipeline Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 29 September–3 October 2002; Volume 36207, pp. 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Elkady, T.Y.; Al-Mahbashi, A.; Dafalla, M.; Al-Shamrani, M. Effect of compaction state on the soil water characteristic curves of sand–natural expansive clay mixtures. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapullaiah, P.V.; Sridharan, A.; Stalin, V.K. Evaluation of bentonite and sand mixtures as liners. In Environmental Geotechnics; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 1998; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guney, Y.; Cetin, B.; Aydilek, A.H.; Tanyu, B.F.; Koparal, S. Utilization of sepiolite materials as a bottom liner material in solid waste landfills. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, A.A.; Elkady, T.Y. Investigation of the hydraulic efficiency of sand-natural expansive clay mixtures. GEOMATE J. 2016, 11, 2410–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.M.; Sudha, A.R. A study on the effect of chemicals on the geotechnical properties of bentonite and bentonite-sand mixtures as clay liners. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2016, 5, 660–666. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Effect of Freeze–Thaw Cycles on the Water Absorption and Retention Capacity of Unsaturated Expansive Soil Liners. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2025, 39, 04025012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafalla, M.A.; Al-Mahbashi, A.M. Effect of adding natural clay on the water retention curve of sand-bentonite mixtures. In Unsaturated Soils: Research & Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Dafalla, M. Effects of Expansive Clay Content on the Hydromechanical Behavior of Liners Under Freeze-Thaw Conditions. Minerals 2025, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regadío García, M.; Black, J.A.; Thornton, S.F. The role of natural clays in the sustainability of landfill liners. Detritus 2020, 12, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, M.; Nara, Y.; Kato, M.; Nishimura, T. Effects of clay-mineral type and content on the hydraulic conductivity of bentonite–sand mixtures made of Kunigel bentonite from Japan. Clay Miner. 2018, 53, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roushangar, K.; Alami, M.T.; Houshyar, Y. Experimental investigation of bentonite impact on self-healing of clay soils. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.N.; Siddiquie, A. Performance Evaluation of Various Clay Minerals for Use as a Liner in Sanitary Landfill. Int. J. Innov. Res. Technol. 2024, 11, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Salemi, N.; Abtahi, S.M.; Rowshanzamir, M.A.; Hejazi, S.M. Improving hydraulic performance and durability of sandwich clay liner using super-absorbent polymer. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2019, 21, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Dafalla, M.; Shaker, A.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Sustainable and stable clay sand liners over time. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Dafalla, M.; Al-Shamrani, M. Long-term performance of liners subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. Water 2022, 14, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Alnuaim, A. Effect of dynamic loads on the long-term efficiency of liner layers. Buildings 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.A.; Benson, C.H. Effect of freeze-thaw on the hydraulic conductivity of three compacted clays from Wisconsin. Transp. Res. Rec. 1993, 1369, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Leuther, F.; Schlüter, S. Impact of freeze–thaw cycles on soil structure and soil hydraulic properties. Soil 2021, 7, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, W.; Xiao, Y.; Nie, R.; Zhou, W.; Liu, W. Investigating strength and deformation characteristics of heavy-haul railway embankment materials using large-scale undrained cyclic triaxial tests. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04017074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Huang, X.; Li, R.; Luo, Q.; Shiau, J.; Wang, Y.; Liao, C. Dynamic behavior and deformation of calcareous sand under cyclic loading. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 199, 109730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.T.P.; Chang, I.; Cho, G.C. Soil water retention and vegetation survivability improvement using microbial biopolymers in drylands. Geomech. Eng. 2019, 17, 475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr-El-Din, H.A.; Al-Mulhem, A.A.; Lynn, J.D. Evaluation of clay stabilizers for a sandstone field in central Saudi Arabia. SPE Prod. Facil. 1999, 14, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirathanathaworn, T.; Nontananandh, S.; Chantawarangul, K. Stabilization of clayey sand using fly ash mixed with small amount of lime, GTE 93-98. In Proceedings of the 9th National Convention on Civil Engineering, Petchaburi, Thailand, 19–21 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dafalla, M.A.; Al-Shamrani, M.A.; Obaid, A. Reducing erosion along the surface of sloping clay-sand liners. In Geo-Congress 2013: Stability and Performance of Slopes and Embankments III; Amer Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2013; pp. 1841–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Mera, C.M.; Ariza, C.A.F.; Correa, F.B.C. Use of silica nanoparticles for stabilizing fines in Ottawa sand packed beds. Tech. Brief. 2013, 77, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadasi, R.; Rostami, A.; Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Application of nanofluids for treating fines migration during hydraulic fracturing: Experimental study and mechanistic understanding. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2019, 3, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadizadeh, A.; Sadeghein, A.; Riahi, S. The use of nanotechnology to prevent and mitigate fine migration: A comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2022, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Im, J.; Cho, G.C. Soil–hydraulic conductivity control via a biopolymer treatment-induced bio-clogging effect. Geotech. Struct. Eng. Cong. 2016, 2016, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Cabalar, A.F.; Awraheem, M.H.; Khalaf, M.M. Geotechnical properties of a low-plasticity clay with biopolymer. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biju, M.S.; Arnepalli, D.N. Effect of biopolymers on permeability of sand-bentonite mixtures. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2020, 12, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Li, S.S.; Ma, L.; Geng, X.Y. Performance of soils enhanced with eco-friendly biopolymers in unconfined compression strength tests and fatigue loading tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; So, P.S.; Chen, X.W. A water retention model considering biopolymer-soil interactions. J. Hydrol. 2020, 586, 124874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vydehi, K.V.; Moghal, A.A.B. Effect of biopolymeric stabilization on the strength and compressibility characteristics of cohesiv soil. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04021428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almajed, A.; Al-Mahbashi, A.M. Contribution of Fine Contents on Retention Characteristics of Biopolymer-Stabilized Sand. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Almajed, A. The role of biopolymers on the water retention capacity of stabilized sand. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Almajed, A. Effect of Dehydration on the Resilient Modulus of Biopolymer-Treated Sandy Soil for Pavement Construction. Polymers 2025, 17, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Ryu, S.; Chang, I. Linear regression to predict the unconfined compressive strength of biopolymer-based soil treatment (BPST). In Smart Geotechnics for Smart Societies; Zhussupbekov, A., Sarsembayeva, A., Kaliakin, V.N., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Vakili, A.H.; Awam, A.; Keskin, İ. Innovative application of recycled waste biopolymers to enhance the efficiency of traditional compacted clay liners of landfill systems: Mitigating leachate impact. Mater. Lett. 2024, 365, 136487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Zhuang, H.; Fan, J.Y.; Xia, W.Y.; Wan, J.L.; Che, C.; Du, Y.J. Biopolymer-amended geosynthetic clay liners for landfills and contaminated sites: Gas/hydraulic performance. Environ. Res. 2025, 278, 121714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D854-2023; Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by the Water Displacement Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D6913-2025; Standard Test Methods for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Soils Using Sieve Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2487-17; Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7928; Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Fine-Grained Soils Using the Sedimentation (Hydrometer) Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4318-2017; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Rafi, A. Engineering Properties and Mineralogical Composition of Expansive Clays in Al-Qatif Area. Doctoral Dissertation, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafalla, M.; Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Al-Shamrani, M. X-Ray Diffraction Assessment of Expanding Minerals in a Semi-Arid Environment. Minerals 2025, 15, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Elkady, T.Y.; Alrefeai, T.O. Soil water characteristic curve and improvement in lime treated expansive soil. Geomech. Eng. 2015, 8, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemboye, K.; Almajed, A.; Hamid, W.; Arab, M. Permeability investigation on sand treated using enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation and biopolymers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2021, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Geng, X. Mechanical behaviours of biopolymers reinforced natural soil. Struct. Eng. Mech. Int. J. 2023, 88, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Ivanov, V.; Karak, N.; Jonkers, H. (Eds.) Biopolymers and Biotech Admixtures for Eco-Efficient Construction Materials; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain, M.S.; Jameel, E.; Mohanta, B.; Dhara, A.K.; Alkahtani, S.; Nayak, A.K. Alginates: Sources, structure, and properties. In Alginates in Drug Delivery; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshizadeh, A.; Khayat, N.; Horpibulsuk, S. Surface stabilization of clay using sodium alginate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrakheil, K.S.; Shah, S.S.A.; Naveed, M. A Comparison of Cement and Guar Gum Stabilisation of Oxford Clay Under Controlled Wetting and Drying Cycles. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Cement Production and CO2 Emissions: Global Trends and Outlooks; IEA: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/cement (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Ahn, S.; Ryou, J.-E.; Ahn, K.; Lee, C.; Lee, J.-D.; Jung, J. Evaluation of Dynamic Properties of Sodium-Alginate-Reinforced Soil Using A Resonant-Column Test. Materials 2021, 14, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Ryou, J.E.; Yang, B.; Hong, W.T. Pore network approach to evaluate the injection characteristics of biopolymer solution into soil. Smart Struct. Syst. Int. J. 2024, 34, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D698-12e2; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort (12,400 ft-lbf/ft3 (600 kN-m/m3)). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM D5856; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Hydraulic Conductivity of Porous Material Using a Rigid-Wall, Compaction-Mold Permeameter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Cazaux, D.; Didier, G. Comparison between various Field and Laboratory Measurements of the Hydraulic Conductivity of three Clay Liners. In Evaluation and Remediation of Low Permeability and Dual Porosity Environments; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paseka, S. Comparison of Field And Laboratory Methods for the Assessment of Soil Hydraulic Conductivity. In Proceedings of the 24th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2024, Albena, Bulgaria, 3–9 July 2024; Trofymchuk, O., Rivza, B., Eds.; STEF92 Technology: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, R.; Sheikh, V.; Hossein-Alizadeh, M.; Rezaii-Moghadam, H. Effect of soil sample size on saturated soil hydraulic conductivity. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2017, 48, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagarello, V.; D’Asaro, F.; Iovino, M. A field assessment of the Simplified Falling Head technique to measure the saturated soil hydraulic conductivity. Geoderma 2012, 187, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1140-17; Standard Test Methods for Determining the Amount of Material Finer than 75-μm (No. 200) Sieve in Soils by Washing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of crosslinking agents and reservoir conditions on the propagation of fractures in coal reservoirs during hydraulic fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Reddy, R.; Jiang, Q. Crosslinking biopolymers for biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalar, A.; Wiszniewski, M.; Skutnik, Z. Effects of xanthan gum biopolymer on the permeability, odometer, unconfined compressive and triaxial shear behavior of a sand. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2017, 54, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyiri, C.N.; Madivoli, E.S.; Kisato, J.; Gichuki, J.; Kareru, P.G. Biopolymer based hydrogels: Crosslinking strategies and their applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2025, 74, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, E.; Zowada, R.; Foudazi, R. Alginate and guar gum spray application for improving soil aggregation and soil crust integrity. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Im, J.; Prasidhi, A.K.; Cho, G.C. Effects of Xanthan gum biopolymer on soil strengthening. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 74, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Cho, G.C.; Lee, S.W. Geotechnical engineering behaviors of gellan gum biopolymer-treated sand. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J. A review of the application of biopolymers on geotechnical engineering and the strengthening mechanisms between typical biopolymers and soils. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1465709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Chang, I.; Cho, G.C. Advanced biopolymer–based soil strengthening binder with trivalent chromium–xanthan gum crosslinking for wet strength and durability enhancement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Lee, M.; Tran, A.T.P.; Lee, S.; Kwon, Y.M.; Im, J.; Cho, G.C. Review on biopolymer-based soil treatment (BPST) technology in geotechnical engineering practices. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 24, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, A.; Miletić, M.; Auad, M.L. Biopolymers as a sustainable solution for the enhancement of soil mechanical properties. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatehi, H.; Ong, D.E.L.; Yu, J.; Chang, I. Biopolymers as Green Binders for Soil Improvement in Geotechnical Applications: A Review. Geosciences 2021, 11, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, T.; Chen, H.; Ming, W.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, J.; Liang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Bioinspired High-Strength Montmorillonite-Alginate Hybrid Film: The Effect of Different Divalent Metal Cation Crosslinking. Polymers 2022, 14, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.K.; Islam, A.; Khan, R.U.; Rasool, A.; Qureshi, M.A.U.R.; Rizwan, M.; Shuib, R.K.; Rehman, A.; Sadiqa, A. Guar gum/poly ethylene glycol/graphene oxide environmentally friendly hybrid hydrogels for controlled release of boron micronutrient. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 231157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, B.D.; Raj, R. A review on the application of biopolymers (xanthan, agar and guar) for sustainable improvement of soil. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, H. Interactions of Clay Minerals with Biomolecules and Protocells Complex Structures in the Origin of Life: A Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2406210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, J.; Shukla, V.K. Cross-linking in hydrogels—A review. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 2014, 4, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Shaker, A.; Almajed, A. Using Biopolymers to Control Hydraulic Degradation of Natural Expansive-Clay Liners Due to Fines Migration: Long-Term Performance. Polymers 2026, 18, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020272

Al-Mahbashi AM, Shaker A, Almajed A. Using Biopolymers to Control Hydraulic Degradation of Natural Expansive-Clay Liners Due to Fines Migration: Long-Term Performance. Polymers. 2026; 18(2):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020272

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Mahbashi, Ahmed M., Abdullah Shaker, and Abdullah Almajed. 2026. "Using Biopolymers to Control Hydraulic Degradation of Natural Expansive-Clay Liners Due to Fines Migration: Long-Term Performance" Polymers 18, no. 2: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020272

APA StyleAl-Mahbashi, A. M., Shaker, A., & Almajed, A. (2026). Using Biopolymers to Control Hydraulic Degradation of Natural Expansive-Clay Liners Due to Fines Migration: Long-Term Performance. Polymers, 18(2), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020272