Biopolymer Casein–Pullulan Coating of Fe3O4 Nanocomposites for Xanthohumol Encapsulation and Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles

2.2. Preparation of Casein–Pullulan-Coated Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanocomposites

2.3. Preparation of Casein–Pullulan-Coated Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanocomposites Loaded with Xanthohumol

2.3.1. Preparation of Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin/Xanthohumol

2.3.2. Incorporation of Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin/Xanthohumolcomplex into Casein–Pullulan Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

2.3.3. Experimental Design Parameters

2.4. Characterization

2.4.1. Production Yield

2.4.2. Particle Size, Size Distribution, and Zeta Potential

2.4.3. Physical Stability

2.4.4. Drug Loading and Encapsulation Efficiency

2.4.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

2.4.6. High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM)

2.4.7. Molecular Docking

2.4.8. In Vitro Release of Xanthohumol

3. Results and Discussion

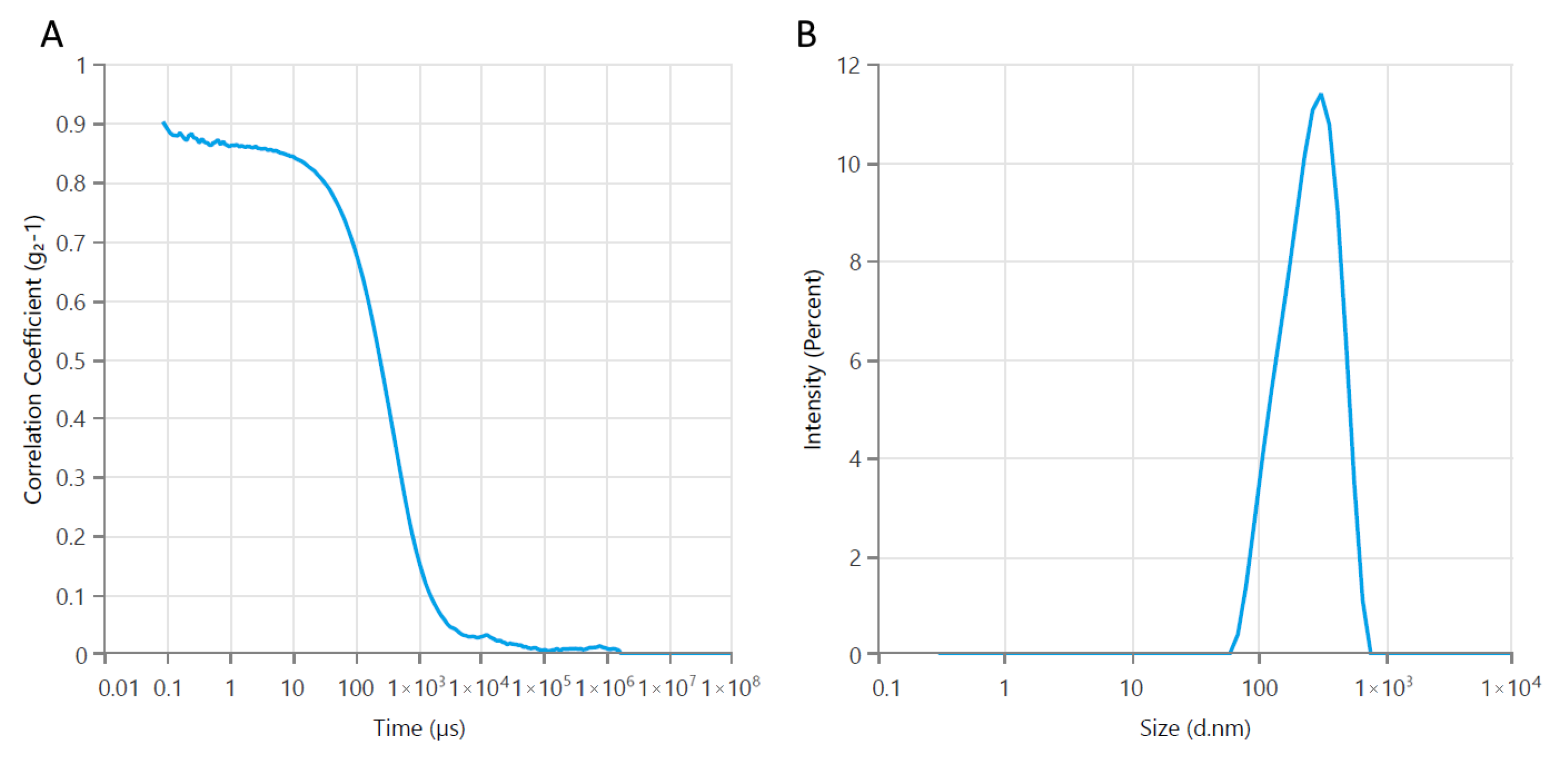

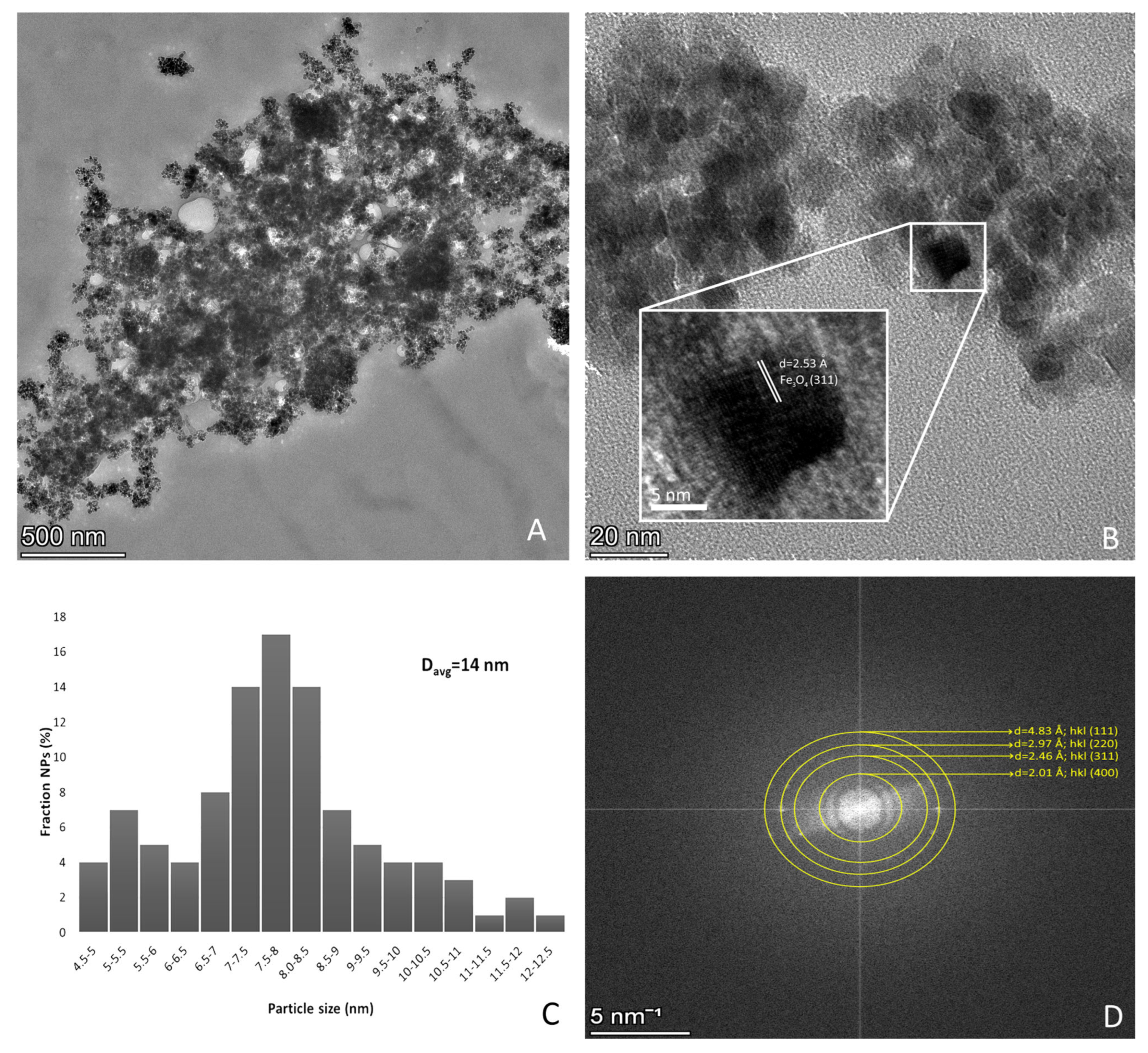

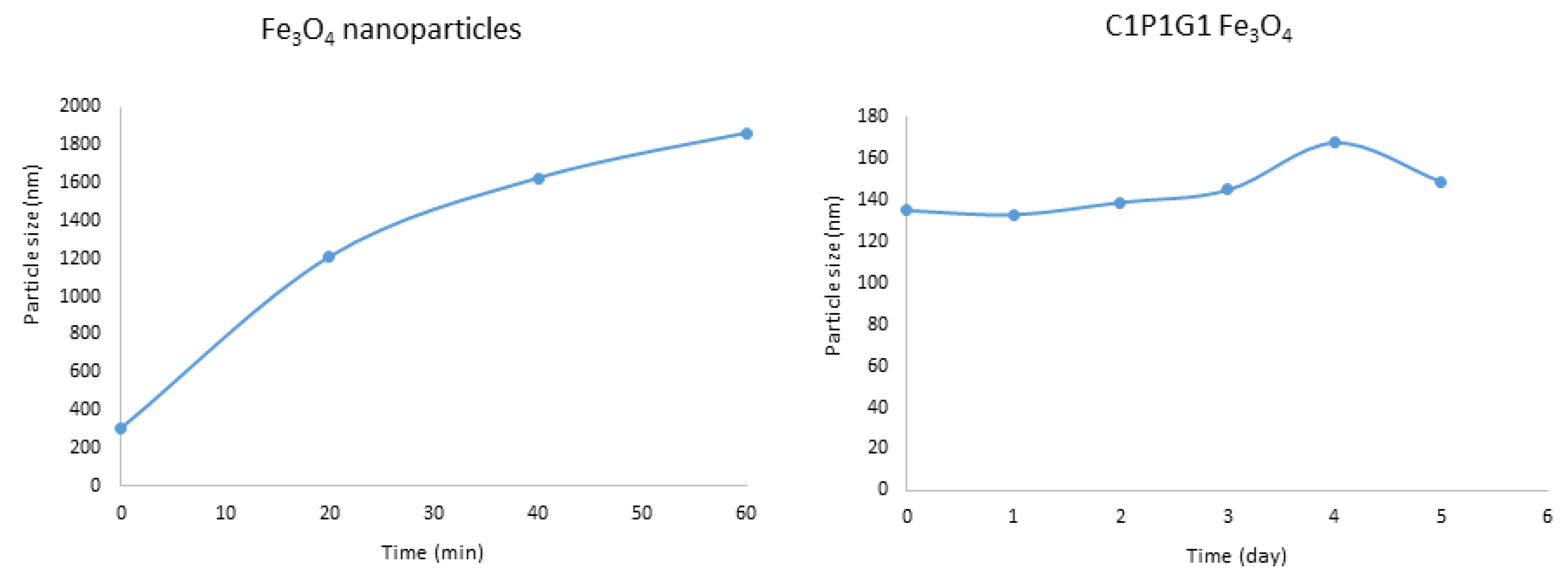

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Bare Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Casein–Pullulan-Coated Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

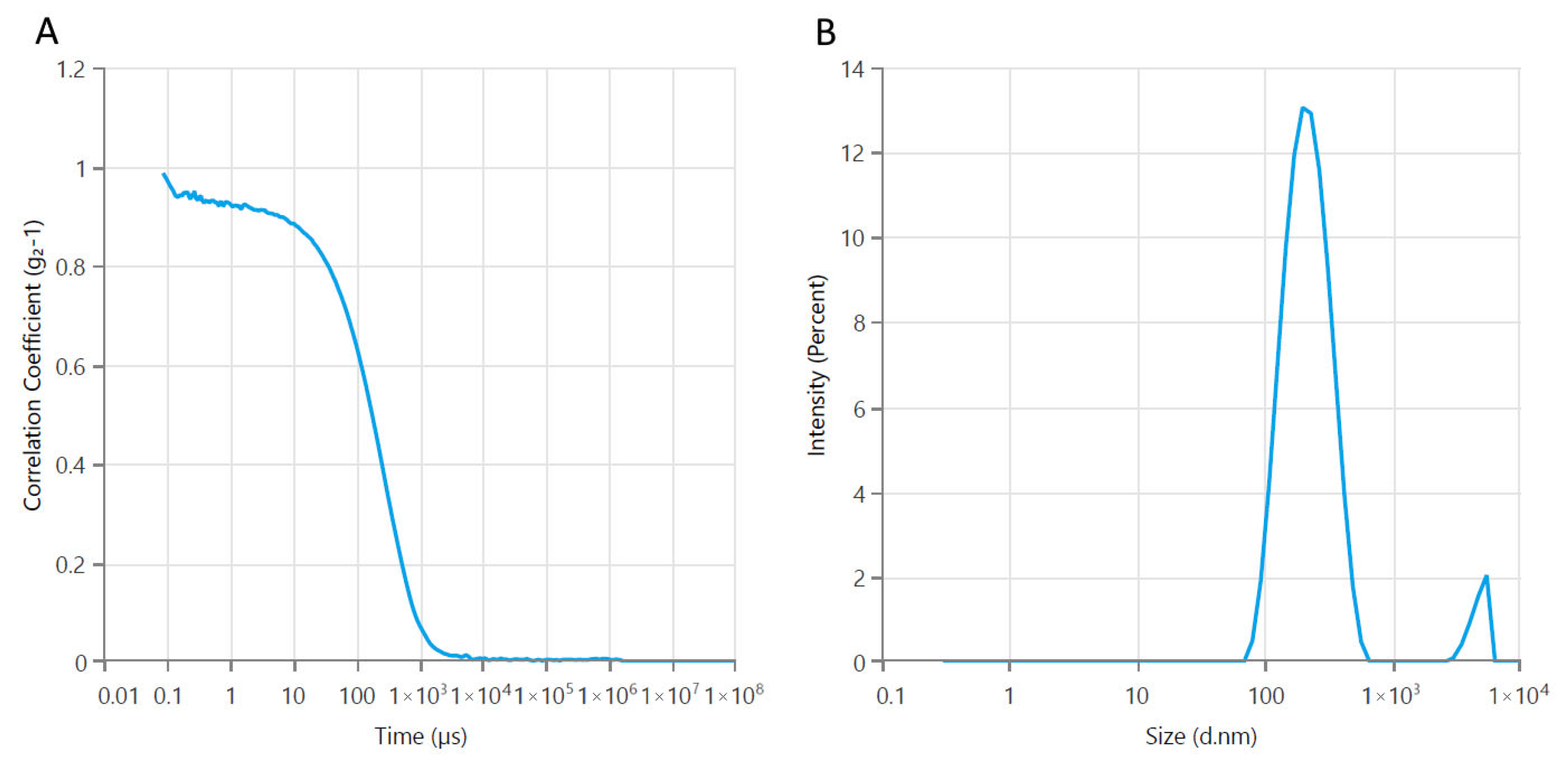

3.2.1. Particle Size and Zeta Potential

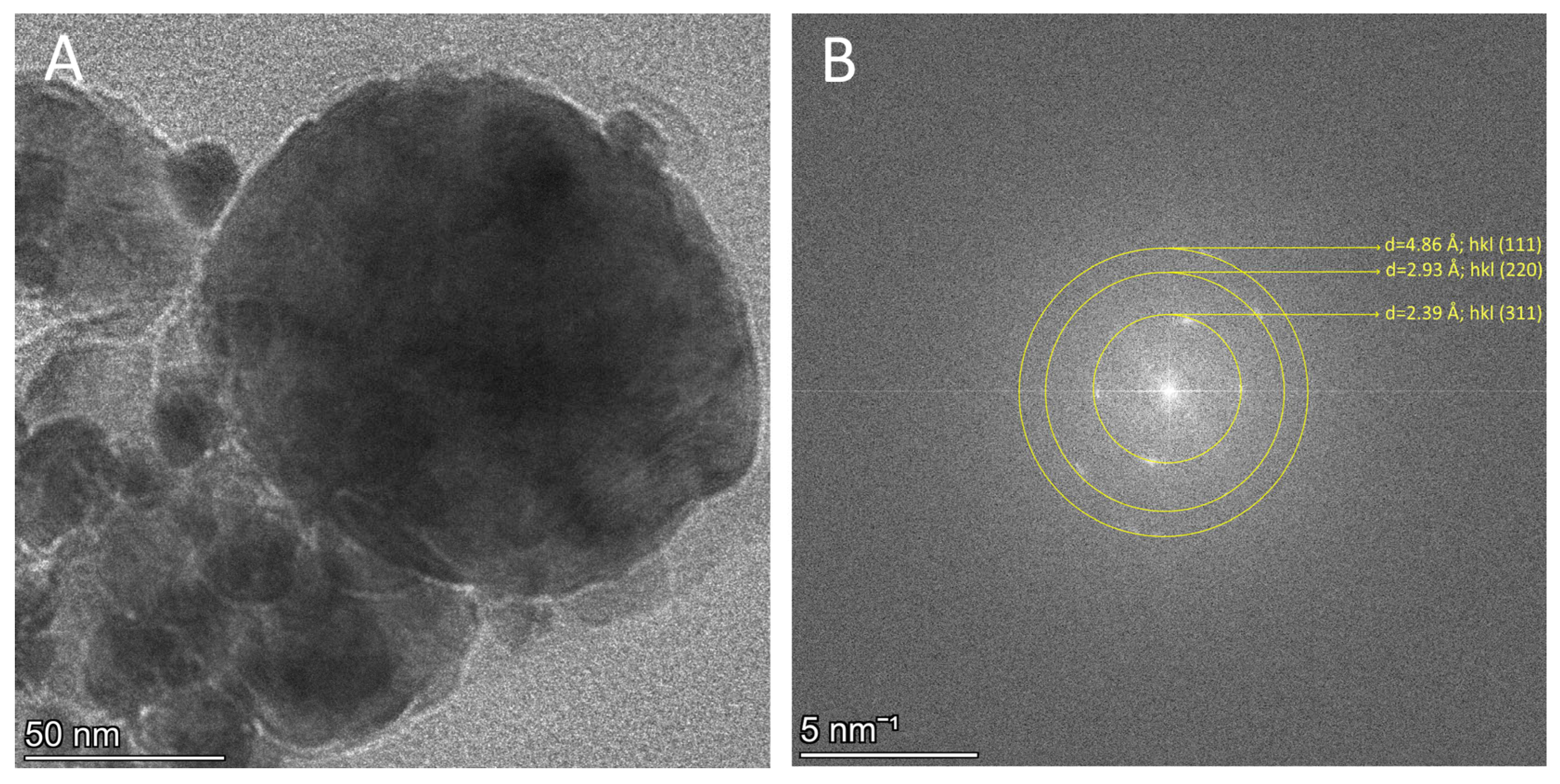

3.2.2. High-Resolution TEM Analysis

3.2.3. SEM-EDX Elemental Analysis of the Composite

3.2.4. Colloidal Stability in PBS

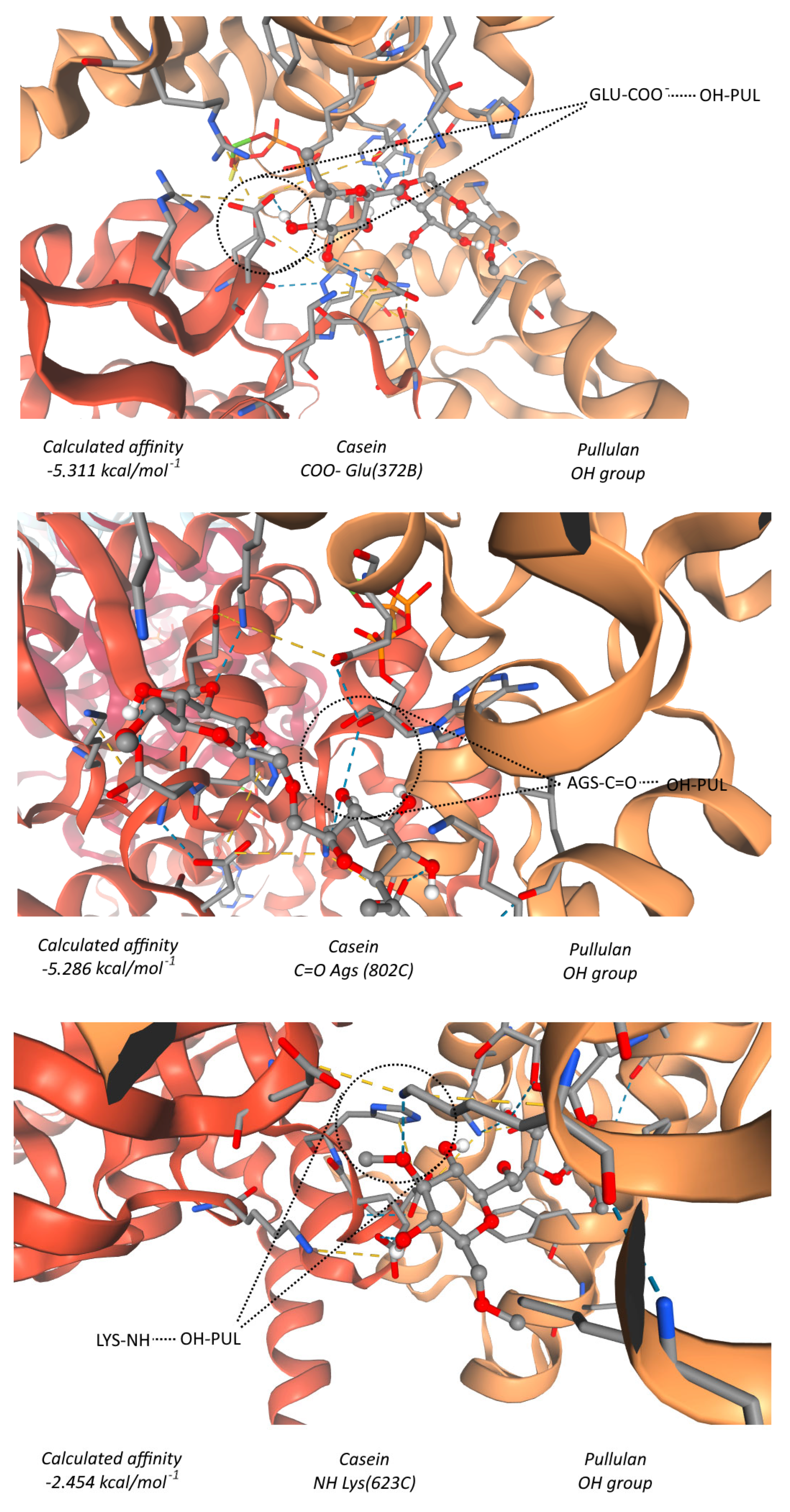

3.2.5. Molecular Docking Analysis

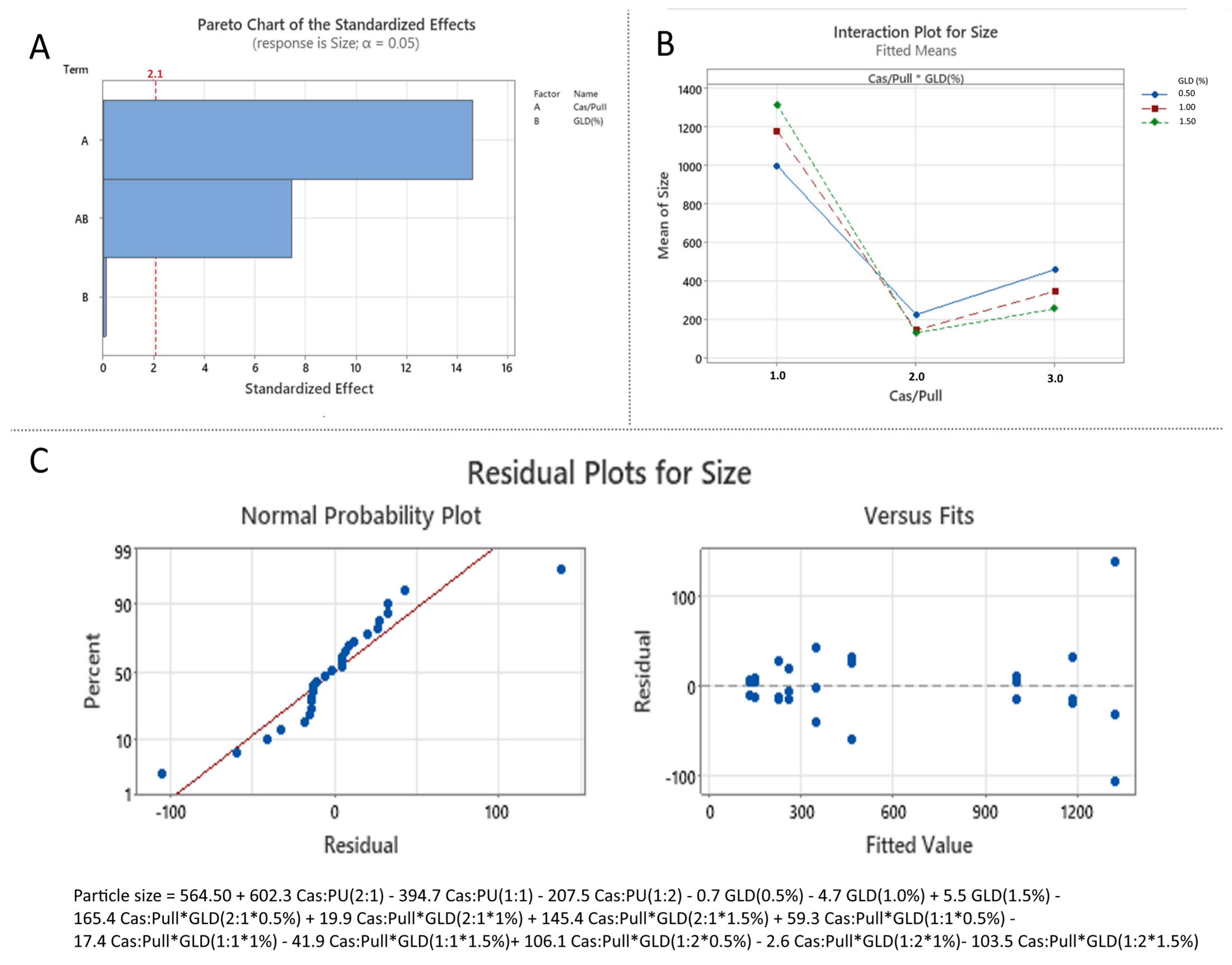

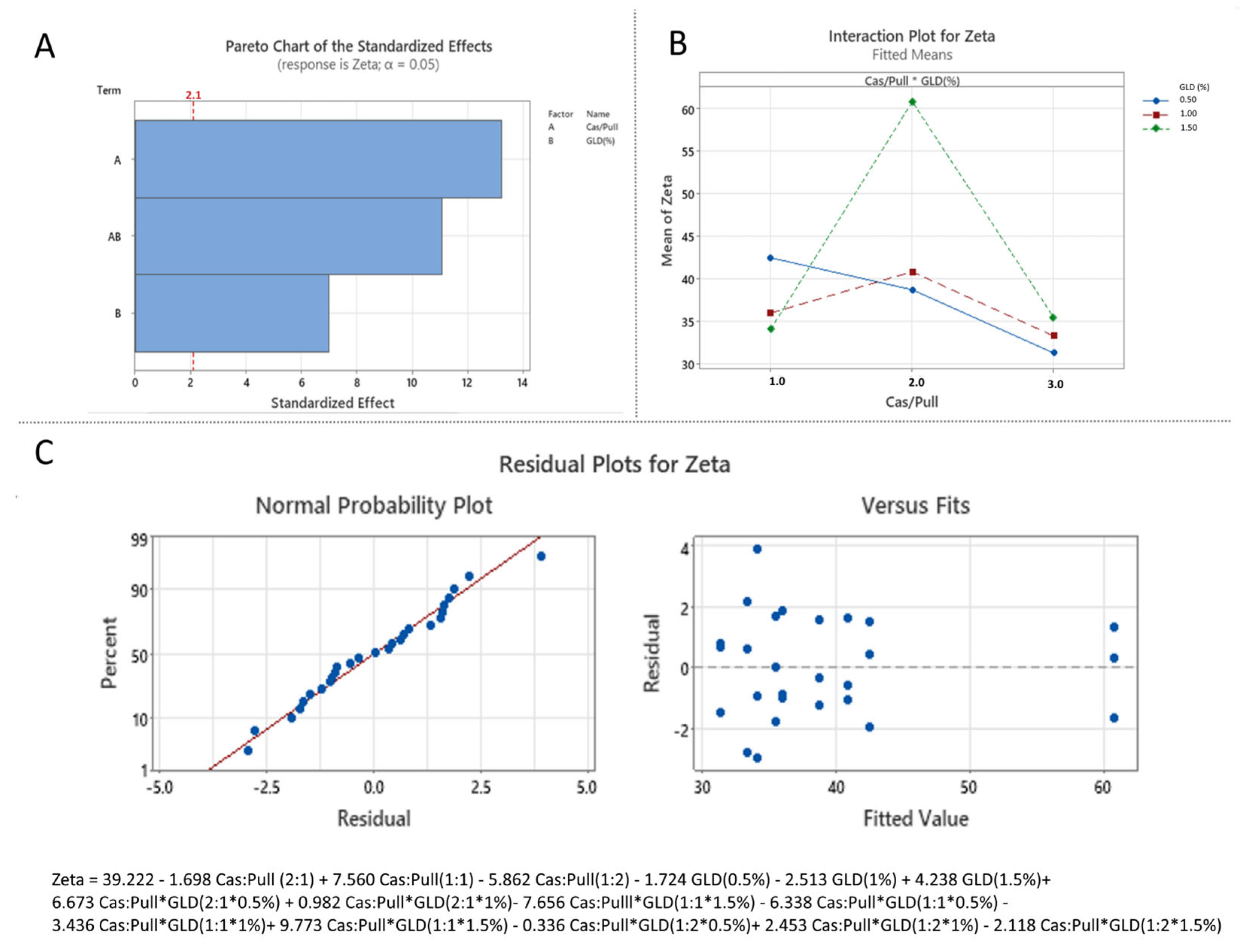

3.3. Optimization of Xanthohumol-Loaded Casein–Pullulan Fe3O4 Nanocomposites via 32 Factorial Design

3.3.1. Effect of the Independent over Particle Size (Effect of Formulation Variables on Particle Size)

3.3.2. Effect of Formulation Variables on Zeta Potential

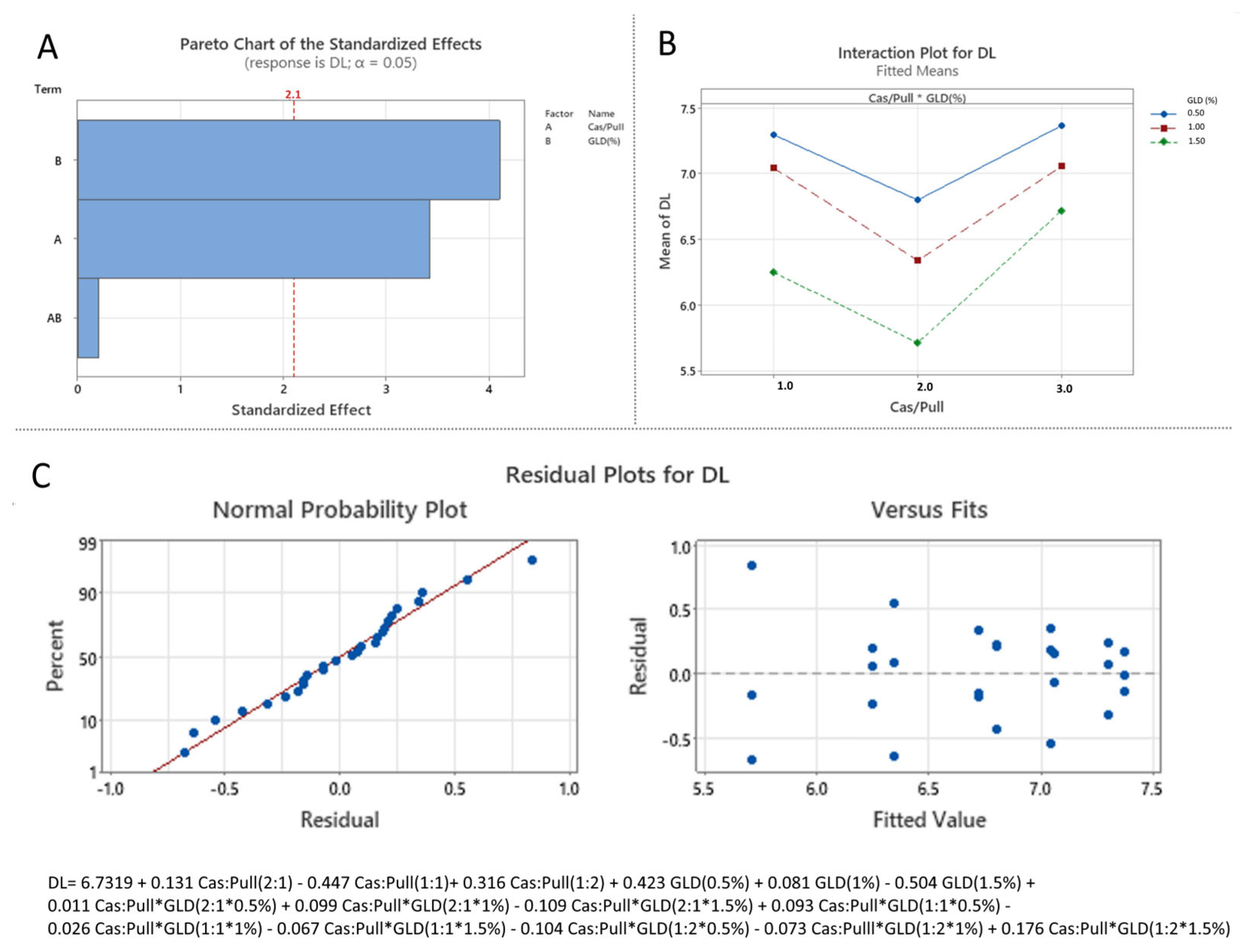

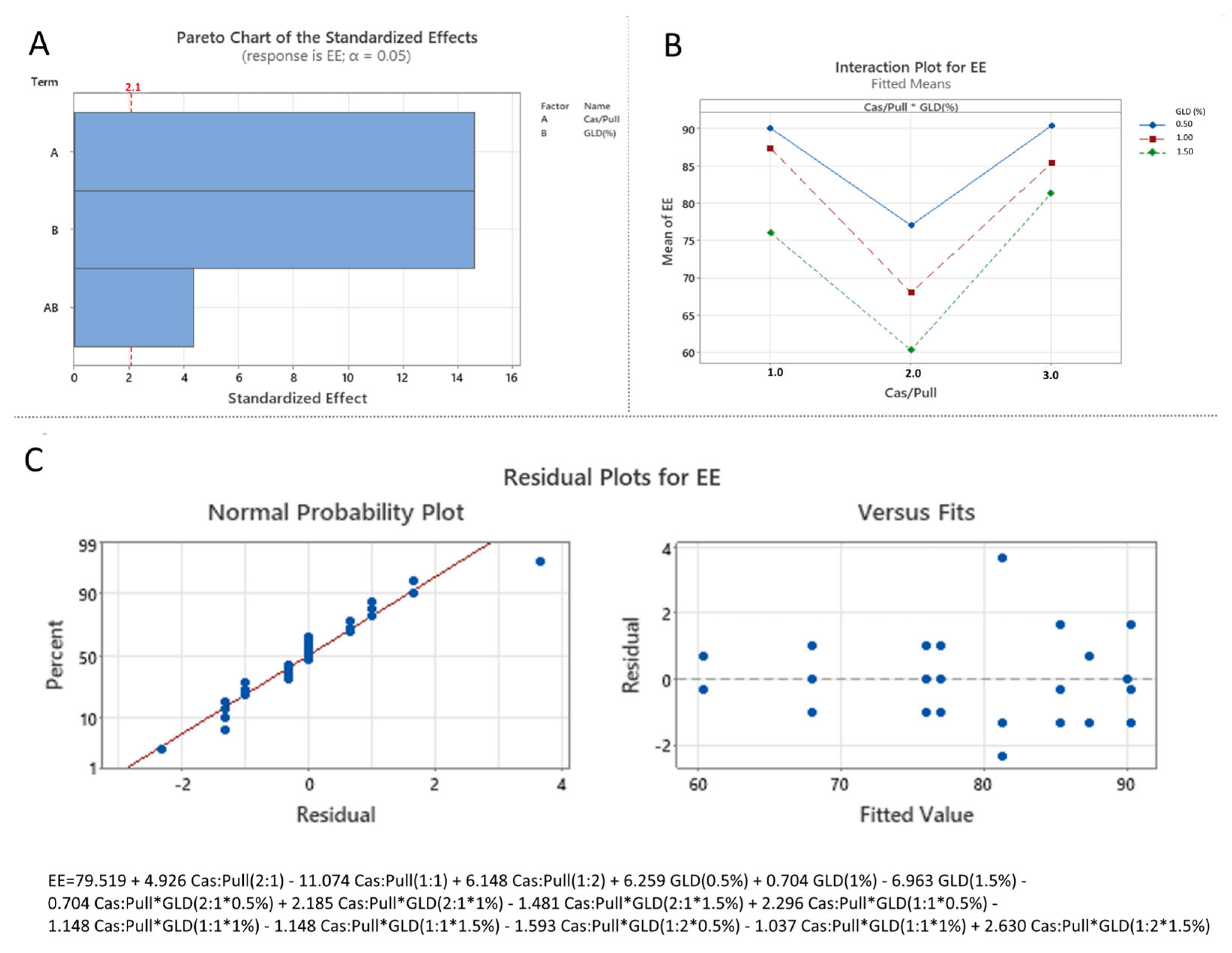

3.3.3. Effect of the Independent over DL and EE

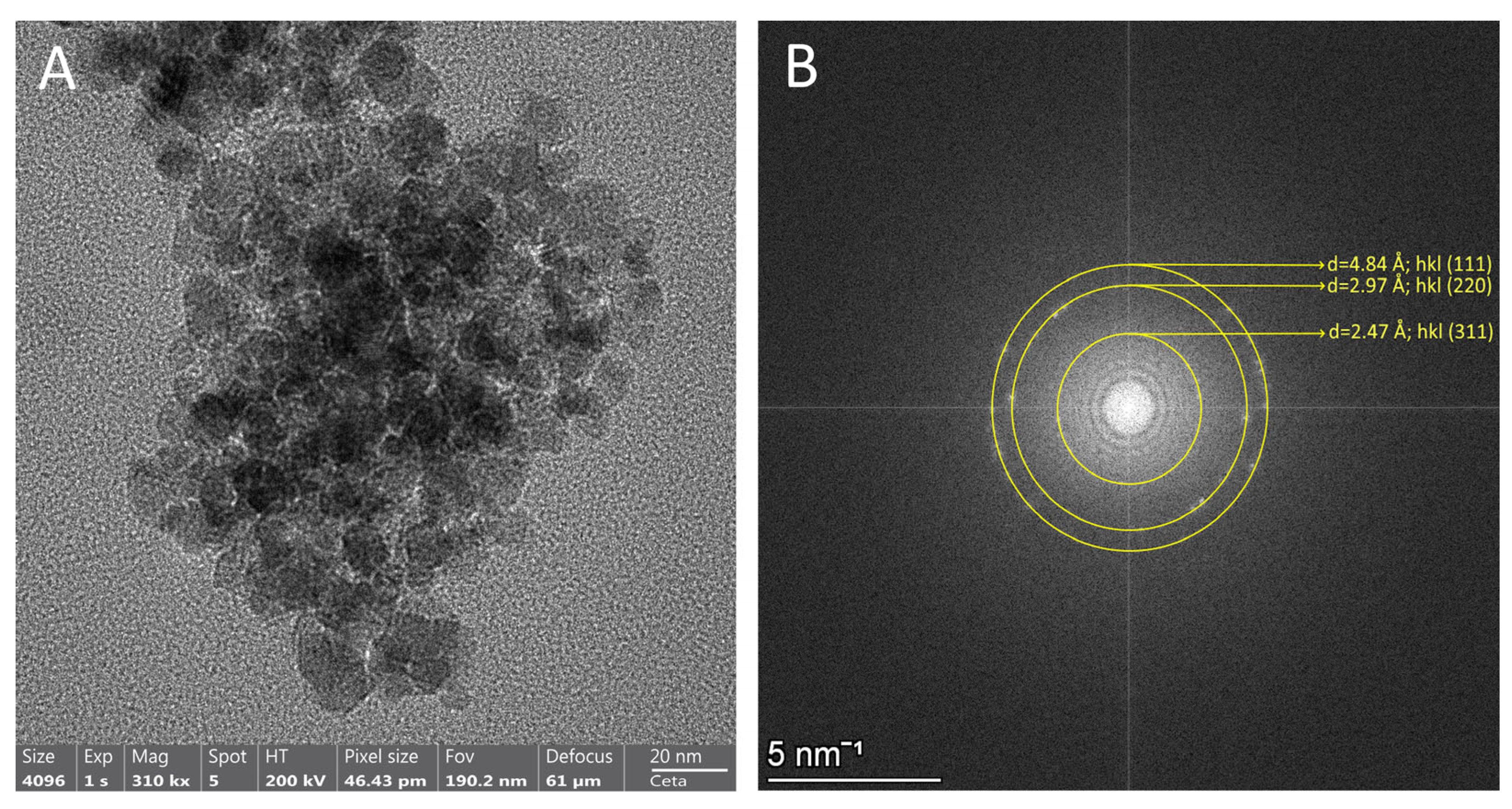

3.4. TEM Analysis of the Structure and Surface Morphology of the Developed Fe3O4 C1P1G1 XN Nanocomposites

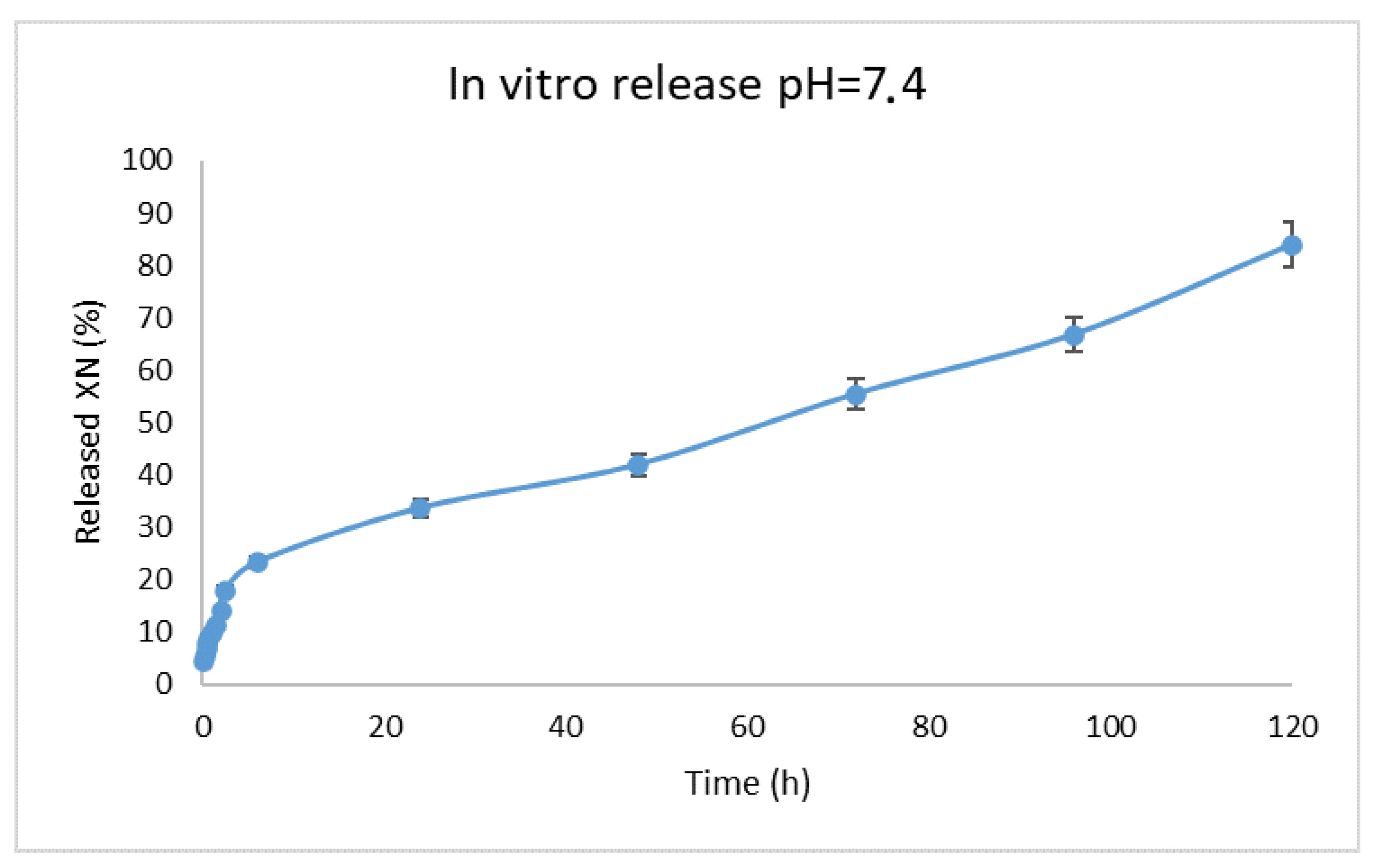

3.5. In Vitro Release Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cas/Pull | Casein–Pullulan |

| DL | Drug loading |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| EE | Entrapment efficiency |

| HP-β-CD | Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin |

| HP-β-CD/XN | Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin/Xanthohumol |

| MN | Magnetic nanoparticles |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| XN | Xanthohumol |

References

- Stiufiuc, G.F.; Stiufiuc, R.I. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Use in Biomedical Field. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arami, H.; Khandhar, A.; Liggitt, D.; Krishnan, K.M. In Vivo Delivery, Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution and Toxicity of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8576–8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruebo, M.; Fernández-Pacheco, R.; Ibarra, M.R.; Santamaría, J. Magnetic Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nano Today 2007, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and Surface Engineering of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Salem-Bekhit, M.M.; Khan, F.; Alshehri, S.; Khan, A.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Wu, H.-F.; Taha, E.I.; Elbagory, I. Unique Properties of Surface-Functionalized Nanoparticles for Bio-Application: Functionalization Mechanisms and Importance in Application. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A.; Xue, J.; Deb, S. Magnetic Nanoparticles in Bone Tissue Engineering. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Forge, D.; Port, M.; Roch, A.; Robic, C.; Vander Elst, L.; Muller, R.N. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Stabilization, Vectorization, Physicochemical Characterizations, and Biological Applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xie, X.; Ouyang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; et al. Pullulan Acetate Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles for Hyper-Thermia: Preparation, Characterization and in Vitro Experiments. Nano Res. 2010, 3, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhd Haniffa, M.; Ching, Y.; Abdullah, L.; Poh, S.; Chuah, C. Review of Bionanocomposite Coating Films and Their Applications. Polymers 2016, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, F. pH-Responsive Transdermal Release from Poly (vinyl alcohol)-Coated Liposomes and Transethosomes: Investigating the Role of Coating in Delayed Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khramtsov, P.; Barkina, I.; Kropaneva, M.; Bochkova, M.; Timganova, V.; Nechaev, A.; Byzov, I.; Zamorina, S.; Yermakov, A.; Rayev, M. Magnetic Nanoclusters Coated with Albumin, Casein, and Gelatin: Size Tuning, Relaxivity, Stability, Protein Corona, and Application in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Immunoassay. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenck, C.; Meier, N.; Heinrich, E.; Grützner, V.; Wiekhorst, F.; Bleul, R. Design and Characterisation of Casein Coated and Drug Loaded Magnetic Nanoparticles for Theranostic Applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26388–26399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oledzka, E. Xanthohumol—A Miracle Molecule with Biological Activities: A Review of Biodegradable Polymeric Carriers and Naturally Derived Compounds for Its Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, A.; Błaszak, B.; Czarnecki, D.; Szulc, J. Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Potential of Xanthohumol in Prevention of Selected Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2025, 30, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchinger, M.; Bieler, L.; Tevini, J.; Vogl, M.; Haschke-Becher, E.; Felder, T.K.; Couillard-Després, S.; Riepl, H.; Urmann, C. Development and Characterization of the Neuroregenerative Xanthohumol C/Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Complex Suitable for Parenteral Administration. Planta Medica 2019, 85, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christaki, S.; Spanidi, E.; Panagiotidou, E.; Athanasopoulou, S.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Mourtzinos, I.; Gardikis, K. Cyclodextrins for the Delivery of Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources: Medicinal, Food and Cosmetics Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresnik, L.; Majerič, P.; Feizpour, D.; Črešnar, K.P.; Rudolf, R. Hybrid Nanostructures of Fe3O4 and Au Prepared via Coprecipitation and Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis. Metals 2024, 14, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.S.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Straubinger, R.M. Pharmaceutical and Physical Properties of Paclitaxel (Taxol) Complexes with Cyclodextrins. J. Pharm. Sci. 1995, 84, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnon, M.; Röhrig, U.F.; Goullieux, M.; Perez, M.A.S.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissDock 2024: Major Enhancements for Small-Molecule Docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W324–W332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukhsar, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Rauf, A.; Zeb, H.; Ur-Rehman, M.; Hemeg, H.A. An Overview of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles: From Synthetic Strategies, Characterization to Antibacterial and Anticancer Applications. Crystals 2022, 12, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R. Superparamagnetic α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 Heterogeneous Nanoparticles with Enhanced Biocompatibility. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Lin, R.; Wang, A.Y.; Yang, L.; Kuang, M.; Qian, W.; Mao, H. Casein-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for High MRI Contrast Enhancement and Efficient Cell Targeting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 4632–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Nunes, C.; Ferreira, L.; Cruz, M.M.; Oliveira, H.; Bastos, V.; Mayoral, Á.; Zhang, Q.; Ferreira, P. Coating of Magnetite Nanoparticles with Fucoidan to Enhance Magnetic Hyperthermia Efficiency. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migneault, I.; Dartiguenave, C.; Bertrand, M.J.; Waldron, K.C. Glutaraldehyde: Behavior in Aqueous Solution, Reaction with Proteins, and Application to Enzyme Crosslinking. BioTechniques 2004, 37, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Yeap, S.P.; Che, H.X.; Low, S.C. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticle by Dynamic Light Scattering. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, S. Relative Strengths of NH··O and CH··O Hydrogen Bonds between Polypeptide Chain Segments. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 16132–16141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyk-Warszyńska, L.; Raszka, K.; Warszyński, P. Interactions of Casein and Polypeptides in Multilayer Films Studied by FTIR and Molecular Dynamics. Polymers 2019, 11, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendler, K.; Thar, J.; Zahn, S.; Kirchner, B. Estimating the Hydrogen Bond Energy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 9529–9536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristo, E.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Zampraka, A. Water Vapour Barrier and Tensile Properties of Composite Caseinate-Pullulan Films: Biopolymer Composition Effects and Impact of Beeswax Lamination. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonin, A.V.; Rusinska-Roszak, D. Quantification of Hydrogen Bond Energy Based on Equations Using Spectroscopic, Structural, QTAIM-Based, and NBO-Based Descriptors Which Calibrated by the Molecular Tailoring Approach. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksiev, A.; Kostova, B. Development and Optimization of the Reservoir-Type Oral Multiparticulate Drug Delivery Systems of Galantamine Hydrobromide. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 78, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burova, T.V.; Grinberg, N.V.; Dubovik, A.S.; Plashchina, I.G.; Usov, A.I.; Grinberg, V.Y. β-Lactoglobulin–Fucoidan Nanocomplexes: Energetics of Formation, Stability, and Oligomeric Structure of the Bound Protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 129, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Tian, Z. Preparation and Characterization of Pullulan-Based Packaging Paper for Fruit Preservation. Molecules 2024, 29, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behram, T.; Pervez, S.; Nawaz, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Jan, A.U.; Rehman, H.U.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, N.M.; Khan, F.A. Development of Pectinase Based Nanocatalyst by Immobilization of Pectinase on Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Using Glutaraldehyde as Crosslinking Agent. Molecules 2023, 28, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Puluhulawa, L.E.; Cindana Mo’o, F.R.; Rusdin, A.; Gazzali, A.M.; Budiman, A. Potential of Pullulan-Based Polymeric Nanoparticles for Improving Drug Physicochemical Properties and Effectiveness. Polymers 2024, 16, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.F.; Santana, M.H.A.; Ré, M.I. Spray-Dried Chitosan Microspheres Cross-Linked with d, l-Glyceraldehyde as a Potential Drug Delivery System: Preparation and Characterization. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2005, 22, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.; Ahmad, M.; Huma, T.; Khalid, I.; Ahmad, I. Evaluation of Low Molecular Weight Cross Linked Chitosan Nanoparticles, to Enhance the Bioavailability of 5-Flourouracil. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 15593258211025353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harish, V.; Almalki, W.H.; Alshehri, A.; Alzahrani, A.; Gupta, M.M.; Alzarea, S.I.; Kazmi, I.; Gulati, M.; Tewari, D.; Gupta, G.; et al. Quality by Design (QbD) Based Method for Estimation of Xanthohumol in Bulk and Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Validation. Molecules 2023, 28, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, T.; Takeshita, T.; Ouchi, M.; Yoshida, K.; Znad, H.; Saptoro, A.; Sarker, Z.I.; Irie, K.; Satho, T.; Nioh, A.; et al. Effect of Double Coating on Microencapsulation of Levofloxacin Using the Particles from Gas-Saturated Solutions Process as a Controlled-Release System. Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradinaru, L.M.; Barbalata Mandru, M.; Drobota, M.; Aflori, M.; Butnaru, M.; Spiridon, M.; Doroftei, F.; Aradoaei, M.; Ciobanu, R.C.; Vlad, S. Composite Materials Based on Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Polyurethane for Improving the Quality of MRI. Polymers 2021, 13, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | |||

| X1: Casein Pullulan ratio | −1 (2:1) | 0 (1:1) | +1 (1:2) |

| X2: Glutaraldehyde concentration | −1 (0.5%) | 0 (1.0%) | +1 (1.5%) |

| Dependent | |||

| Y1: Particle size (nm) | |||

| Y2: Zeta potential (mV) | |||

| Y3: DL (%) | |||

| Y4: EE (%) | |||

| Batch | Levels | Casein (mg/100 mL) | Pullulan (mg/100 mL) | Glutaraldehyde (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4-C2P1G0.5-XN | −1; −1 | 200 | 100 | 0.5 |

| Fe3O4-C2P1G1.0-XN | −1; 0 | 200 | 100 | 1.0 |

| Fe3O4-C2P1G1.5-XN | −1; +1 | 200 | 100 | 1.5 |

| Fe3O4-C1P1G0.5-XN | 0; −1 | 150 | 150 | 0.5 |

| Fe3O4-C1P1G1.0-XN | 0; 0 | 150 | 150 | 1.0 |

| Fe3O4-C1P1G1.5-XN | 0; +1 | 150 | 150 | 1.5 |

| Fe3O4-C1P2G0.5-XN | +1, −1 | 100 | 200 | 0.5 |

| Fe3O4-C1P2G1.0-XN | +1; 0 | 100 | 200 | 1.0 |

| Fe3O4-C1P2G1.5-XN | +1; +1 | 100 | 200 | 1.5 |

| C1P1 G0.5 Fe3O4 | C1P1 G1.0 Fe3O4 | C1P1 G1.5 Fe3O4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | C wt% | O wt% | Fe wt% | C wt% | O wt% | Fe wt% | C wt% | O wt% | Fe wt% |

| 1 | 21.93 | 41.51 | 0.01 | 50.42 | 46.70 | 1.79 | 46.47 | 53.01 | 0.52 |

| 2 | 56.68 | 43.14 | 0.18 | 51.71 | 48.30 | 0.01 | 49.19 | 50.64 | 0.18 |

| 3 | 34.45 | 47.23 | 0.08 | 44.44 | 55.56 | 0.04 | 51.95 | 47.62 | 0.43 |

| 4 | 50.51 | 48.49 | 1.01 | 45.87 | 54.13 | 0.002 | 50.68 | 46.99 | 0.19 |

| 5 | 62.73 | 37.14 | 0.13 | 32.18 | 48.75 | 0.17 | 47.20 | 52.59 | 0.21 |

| 6 | 54.11 | 44.35 | 0.72 | 53.69 | 45.12 | 1.19 | 47.59 | 52.41 | 0.21 |

| 7 | 56.81 | 43.19 | 0.01 | 46.98 | 52.34 | 0.001 | 48.00 | 51.78 | 0.22 |

| 8 | 49.11 | 50.72 | 0.18 | 48.95 | 49.82 | 1.23 | 45.05 | 54.02 | 0.93 |

| 9 | 49.98 | 49.74 | 0.28 | 46.46 | 53.03 | 0.51 | 48.04 | 48.35 | 3.61 |

| 10 | 50.53 | 48.57 | 0.001 | 44.83 | 54.67 | 0.5 | 33.59 | 46.66 | 0.55 |

| Av. ± SD wt% | 48.68 ± 11.9 | 45.40 ± 4.2 | 0.26 ± 0.3 | 46.55 ± 5.8 | 50.84 ± 3.6 | 0.544 ± 0.6 | 46.77 ± 5.1 | 50.40 ± 2.7 | 0.70 ± 1.1 |

| Batch | Size (nm) ± SD | Zeta (mV) ± SD | DL (%) ± SD | EE (%) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4-C2P1G0.5-XN | 985 ± 11 | −42.89 ± 1.4 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 90 ± 0.9 |

| Fe3O4-C2P1G1.0-XN | 1164 ± 23 | −37.86 ± 1.3 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 88 ± 0.6 |

| Fe3O4-C2P1G1.5-XN | 1212 ± 102 | −33.17 ± 2.8 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 76 ± 0.8 |

| Fe3O4-C1P1G0.5-XN | 256 ± 19 | −40.31 ± 1.2 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 77 ± 0.9 |

| Fe3O4-C1P1G1.0-XN | 152 ± 9 | −42.47 ± 1.2 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 68 ± 0.8 |

| Fe3O4-C1P1G1.5-XN | 140 ± 8 | −59.14 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 61 ± 0.5 |

| Fe3O4-C1P2G0.5-XN | 495 ± 42 | −32.11 ± 1.1 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | 90 ± 1.3 |

| Fe3O4-C1P2G1.0-XN | 392 ± 33 | −33.92 ± 2.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 87 ± 1.4 |

| Fe3O4-C1P2G1.5-XN | 278 ±1 4 | −35.51 ± 1.4 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 85 ± 2.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zahariev, N.; Penkov, D.; Boyuklieva, R.; Simeonov, P.; Lukova, P.; Ardasheva, R.; Katsarov, P. Biopolymer Casein–Pullulan Coating of Fe3O4 Nanocomposites for Xanthohumol Encapsulation and Delivery. Polymers 2026, 18, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020256

Zahariev N, Penkov D, Boyuklieva R, Simeonov P, Lukova P, Ardasheva R, Katsarov P. Biopolymer Casein–Pullulan Coating of Fe3O4 Nanocomposites for Xanthohumol Encapsulation and Delivery. Polymers. 2026; 18(2):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020256

Chicago/Turabian StyleZahariev, Nikolay, Dimitar Penkov, Radka Boyuklieva, Plamen Simeonov, Paolina Lukova, Raina Ardasheva, and Plamen Katsarov. 2026. "Biopolymer Casein–Pullulan Coating of Fe3O4 Nanocomposites for Xanthohumol Encapsulation and Delivery" Polymers 18, no. 2: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020256

APA StyleZahariev, N., Penkov, D., Boyuklieva, R., Simeonov, P., Lukova, P., Ardasheva, R., & Katsarov, P. (2026). Biopolymer Casein–Pullulan Coating of Fe3O4 Nanocomposites for Xanthohumol Encapsulation and Delivery. Polymers, 18(2), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020256