Tuning Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Hydrophilization and Coating Stability via the Optimization of Polyethylene Glycol Molecular Weight

Abstract

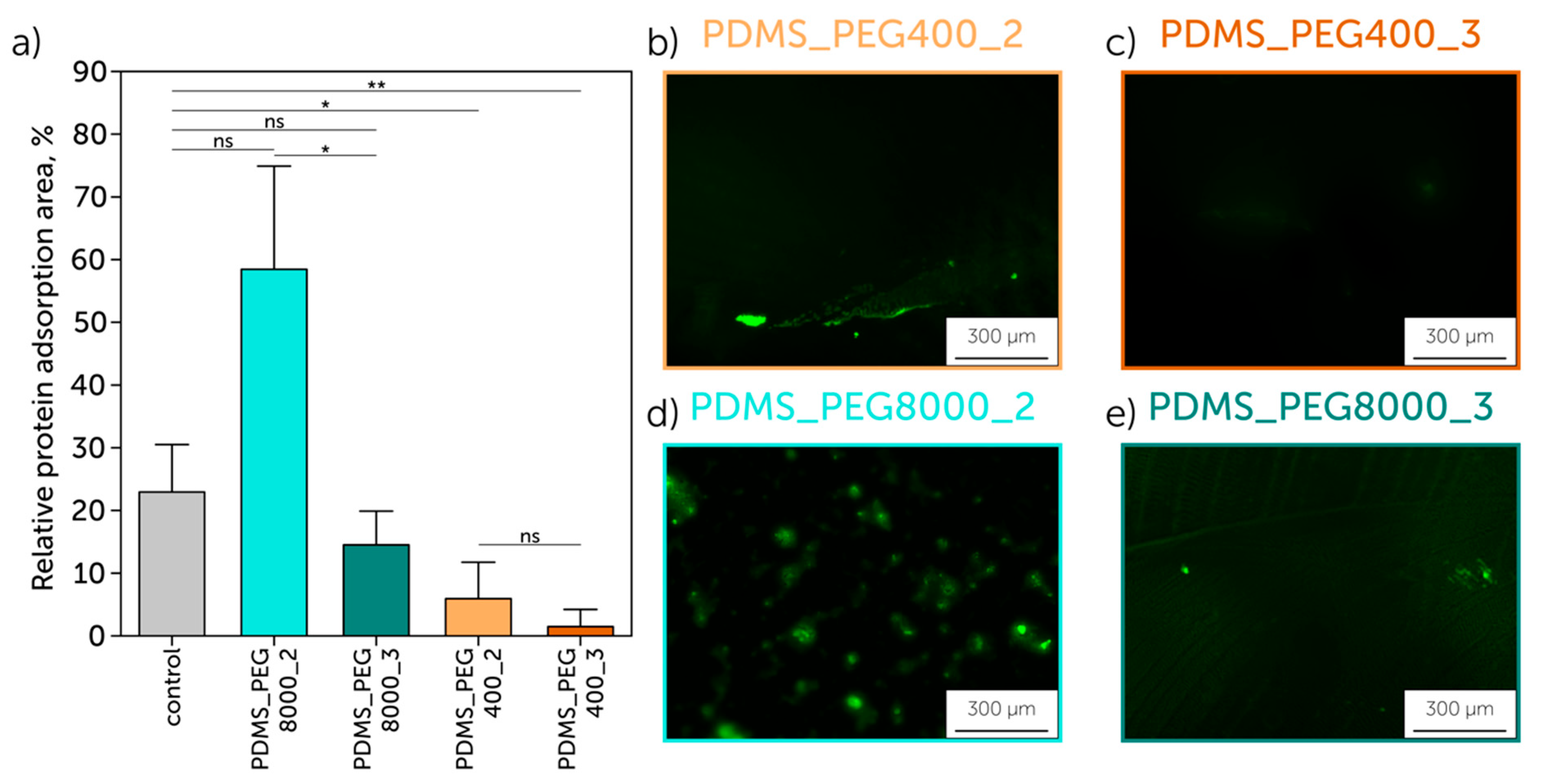

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. PDMS Sample Preparation

2.3. PEG-Based Surface Modification

2.4. Hydrophilization Retainment Performance

2.5. Surface Characterization

2.6. Protein Adsorption

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I |

References

- Plegue, T.J.; Kovach, K.M.; Thompson, A.J.; Potkay, J.A. Stability of Polyethylene Glycol and Zwitterionic Surface Modifications in PDMS Microfluidic Flow Chambers. Langmuir 2018, 34, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puoci, F. (Ed.) Advanced Polymers in Medicine; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-12477-3. [Google Scholar]

- van Poll, M.L.; Zhou, F.; Ramstedt, M.; Hu, L.; Huck, W.T.S. A Self-Assembly Approach to Chemical Micropatterning of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6634–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, A.; Deiwick, A.; Nguyen, A.; Narayan, R.; Shpichka, A.; Kufelt, O.; Kiyan, R.; Bagratashvili, V.; Timashev, P.; Scheper, T.; et al. Hydrogel-Based Microfluidics for Vascular Tissue Engineering. BioNanoMaterials 2016, 17, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.H.; Urban, J.P.G.; Cui, Z.; Cui, Z.F. Development of PDMS Microbioreactor with Well-Defined and Homogenous Culture Environment for Chondrocyte 3-D Culture. Biomed. Microdevices 2006, 8, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belder, D.; Ludwig, M. Surface Modification in Microchip Electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2003, 24, 3595–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Ren, X.; Bachman, M.; Sims, C.E.; Li, G.P.; Allbritton, N. Surface Modification of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Microfluidic Devices by Ultraviolet Polymer Grafting. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 4117–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.P.; Lai, C.C.; Chung, C.K. Polyethylene Glycol Coating for Hydrophilicity Enhancement of Polydimethylsiloxane Self-Driven Microfluidic Chip. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 320, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillborg, H.; Gedde, U.W. Hydrophobicity Recovery of Polydimethylsiloxane after Exposure to Corona Discharges. Polymer 1998, 39, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimenko, K.; Wallace, W.E.; Genzer, J. Surface Modification of Sylgard-184 Poly(Dimethyl Siloxane) Networks by Ultraviolet and Ultraviolet/Ozone Treatment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 254, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.Y.; Lin, Y.Y.; Denq, Y.L.; Shyu, S.S.; Chen, J.K. Surface Modification of Silicone Rubber by Gas Plasma Treatment. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1996, 10, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Chua, Y.C.; Kang, T.G. Oxygen Plasma Treatment for Reducing Hydrophobicity of a Sealed Polydimethylsiloxane Microchannel. Biomicrofluidics 2010, 4, 032204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.; Bertóti, I.; Blazsó, M.; Bánhegyi, G.; Bognar, A.; Szaplonczay, P. Oxidative Damage and Recovery of Silicone Rubber Surfaces. I. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic Study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994, 52, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettlich, H.-J.; Otterbach, F.; Mittermayer, C.; Kaufmann, R.; Klee, D. Plasma-Induced Surface Modifications on Suicone Intraocular Lenses: Chemical Analysis and in Vitro Characterization. Biomaterials 1991, 12, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillborg, H.; Ankner, J.F.; Gedde, U.W.; Smith, G.D.; Yasuda, H.K.; Wikström, K. Crosslinked Polydimethylsiloxane Exposed to Oxygen Plasma Studied by Neutron Reflectometry and Other Surface Specific Techniques. Polymer 2000, 41, 6851–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Abdulali-Kanji, Z.; Dodwell, E.; Horton, J.H.; Oleschuk, R.D. Surface Characterization Using Chemical Force Microscopy and the Flow Performance of Modified Polydimethylsiloxane for Microfluidic Device Applications. Electrophoresis 2003, 24, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, M.-C.; Chen, S.-H.; Chang, Y. Hemocompatibility of Zwitterionic Interfaces and Membranes. Polym. J. 2014, 46, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chao, T.; Chen, S.; Jiang, S. Superlow Fouling Sulfobetaine and Carboxybetaine Polymers on Glass Slides. Langmuir 2006, 22, 10072–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudot, C.; Burkhardt, S.; Haerst, M. Long-Term Stable Modifications of Silicone Elastomer for Improved Hemocompatibility. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, K.M.; Capadona, J.R.; Sen Gupta, A.; Potkay, J.A. The Effects of PEG-Based Surface Modification of PDMS Microchannels on Long-Term Hemocompatibility. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2014, 102, 4195–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yan, H.; Ren, K.; Dai, W.; Wu, H. Convenient Method for Modifying Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) with Poly(Ethylene Glycol) in Microfluidics. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 6627–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Shin, H.-S.; Park, K.; Han, D.K. Surface Grafting of Blood Compatible Zwitterionic Poly(Ethylene Glycol) on Diamond-like Carbon-Coated Stent. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2011, 22, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.C.; Chung, C.K. Hydrophilicity and Optic Property of Polyethylene Glycol Coating on Polydimethylsiloxane for Fast Prototyping and Its Application to Backlight Microfluidic Chip. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 389, 125606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pardo, I.; Van der Ven, L.; Van Benthem, R.; De With, G.; Esteves, A. Hydrophilic Self-Replenishing Coatings with Long-Term Water Stability for Anti-Fouling Applications. Coatings 2018, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, X.; Luo, Q.; Liu, B. Environmentally Friendly Surface Modification of PDMS Using PEG Polymer Brush. Electrophoresis 2009, 30, 3174–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumpson, P.J. Estimation of Inelastic Mean Free Paths for Polymers and Other Organic Materials: Use of Quantitative Structure–Property Relationships. Surf. Interface Anal. 2001, 31, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D.; Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: An Open-Source Software for SPM Data Analysis. Open Phys. 2012, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremov, Y.M.; Wang, W.-H.; Hardy, S.D.; Geahlen, R.L.; Raman, A. Measuring Nanoscale Viscoelastic Parameters of Cells Directly from AFM Force-Displacement Curves. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamson, G.; Briggs, D. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA300 Database. J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70, A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louette, P.; Bodino, F.; Pireaux, J.-J. Poly(Dimethyl Siloxane) (PDMS) XPS Reference Core Level and Energy Loss Spectra. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2005, 12, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780470093078. [Google Scholar]

- Afanas’ev, V.P.; Lobanova, L.G.; Selyakov, D.N.; Semenov-Shefov, M.A. Effect of Nanocoating Morphology on the Signal of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2144, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiser, S.; Schütz, U.; Hegemann, D. Top-down Approach to Attach Liquid Polyethylene Glycol to Solid Surfaces by Plasma Interaction. Plasma Process. Polym. 2020, 17, 1900211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj Singh, T.R.; McCarron, P.A.; Woolfson, A.D.; Donnelly, R.F. Investigation of Swelling and Network Parameters of Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Crosslinked Poly(Methyl Vinyl Ether-Co-Maleic Acid) Hydrogels. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökaltun, A.; Kang, Y.B.; Yarmush, M.L.; Usta, O.B.; Asatekin, A. Simple Surface Modification of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) via Surface Segregating Smart Polymers for Biomicrofluidics. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demming, S.; Lesche, C.; Schmolke, H.; Klages, C.; Büttgenbach, S. Characterization of Long-term Stability of Hydrophilized PEG-grafted PDMS within Different Media for Biotechnological and Pharmaceutical Applications. Phys. Status Solidi A 2011, 208, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Dhayal, M.; Govind; Shivaprasad, S.M.; Jain, S.C. Surface Characterization of Plasma-Treated and PEG-Grafted PDMS for Micro Fluidic Applications. Vacuum 2007, 81, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T. Blood Flow Measurement. In Comprehensive Biomedical Physics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, L.; Guo, H.; Zuckermann, M.J. Conformation of Polymer Brushes under Shear: Chain Tilting and Stretching. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2289–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Gonçalves, I.M.; Borges, J.; Faustino, V.; Soares, D.; Vaz, F.; Minas, G.; Lima, R.; Pinho, D. Polydimethylsiloxane Surface Modification of Microfluidic Devices for Blood Plasma Separation. Polymers 2024, 16, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. TURBULENT FLOWS OVER ROUGH WALLS. Annu. Rev. Fluid. Mech. 2004, 36, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi Menon, E. Fluid Flow in Pipes. In Transmission Pipeline Calculations and Simulations Manual; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 149–234. [Google Scholar]

- Schrott, W.; Slouka, Z.; Červenka, P.; Ston, J.; Nebyla, M.; Přibyl, M.; Šnita, D. Study on Surface Properties of PDMS Microfluidic Chips Treated with Albumin. Biomicrofluidics 2009, 3, 044101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabaghi, M.; Shahriari, S.; Saraei, N.; Da, K.; Chandiramohan, A.; Selvaganapathy, P.R.; Hirota, J.A. Surface Modification of PDMS-Based Microfluidic Devices with Collagen Using Polydopamine as a Spacer to Enhance Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cell Adhesion. Micromachines 2021, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, T.S.; Tighe, B.J. Mechanical Properties of Contact Lenses: The Contribution of Measurement Techniques and Clinical Feedback to 50 Years of Materials Development. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2017, 40, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Hou, Y.; Chu, Z.; Wei, Q. Soft Overcomes the Hard: Flexible Materials Adapt to Cell Adhesion to Promote Cell Mechanotransduction. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Fu, J. Modulating Surface Stiffness of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) with Kiloelectronvolt Ion Patterning. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2015, 25, 065006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.-P.-D.; Yang, M.-C.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L. Evaluation of Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses Based on Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Dialkanol and Hydrophilic Polymers. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 206, 111957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Qi, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, G.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z. Anti-Marine Biofouling Adhesion Performance and Mechanism of PDMS Fouling-Release Coating Containing PS-PEG Hydrogel. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.; Zimudzi, T.J.; Geise, G.M.; Hickner, M.A. Increased Hydrogel Swelling Induced by Absorption of Small Molecules. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14263–14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, S.; Edahiro, J.; Sumaru, K.; Kanamori, T. Surface Modification of Polydimethylsiloxane with Photo-Grafted Poly(Ethylene Glycol) for Micropatterned Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2008, 63, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, M.; Beaudoin, S. Surface Forces and Protein Adsorption on Dextran- and Polyethylene Glycol-Modified Polydimethylsiloxane. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 81, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Element Concentration, % | C/Si Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | O | Si | ||

| PDMS (non-modified) a | 41.2 | 35.3 | 23.2 | 1.77 |

| PDMS_PEG400_2 | 33.1 | 43.6 | 23.3 | 1.42 |

| PDMS_PEG400_3 | 35.9 | 42.4 | 21.7 | 1.65 |

| PDMS_PEG8000_2 | 59.6 | 31.2 | 9.2 | 6.45 |

| PDMS_PEG8000_3 | 43.1 | 38.4 | 18.5 | 2.33 |

| Coating Composition | Contact Angle, ° 1 | Stability of Coating, Hours 2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG35000 | 46 | 20 | [8] |

| PEG-amine | 70 | – | [25] |

| PEG-silane | ~10 | 24 | [33] |

| Poly(glycidyl methacrylate) and poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) | 25–35 | >168 | [33] |

| PEG400 | 10–20 | >500 | This study |

| PEG8000 | 10–30 | >500 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golubchikov, D.; Oleynichenko, K.; Murashko, A.; Efremov, Y.; Safaryan, S.; Pereira, F.D.A.S.; Nifontova, G.; Solovieva, A.; Shpichka, A.; Timashev, P. Tuning Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Hydrophilization and Coating Stability via the Optimization of Polyethylene Glycol Molecular Weight. Polymers 2025, 17, 3296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243296

Golubchikov D, Oleynichenko K, Murashko A, Efremov Y, Safaryan S, Pereira FDAS, Nifontova G, Solovieva A, Shpichka A, Timashev P. Tuning Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Hydrophilization and Coating Stability via the Optimization of Polyethylene Glycol Molecular Weight. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243296

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolubchikov, Daniil, Konstantin Oleynichenko, Anton Murashko, Yuri Efremov, Sofia Safaryan, Frederico D. A. S. Pereira, Galina Nifontova, Anna Solovieva, Anastasia Shpichka, and Peter Timashev. 2025. "Tuning Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Hydrophilization and Coating Stability via the Optimization of Polyethylene Glycol Molecular Weight" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243296

APA StyleGolubchikov, D., Oleynichenko, K., Murashko, A., Efremov, Y., Safaryan, S., Pereira, F. D. A. S., Nifontova, G., Solovieva, A., Shpichka, A., & Timashev, P. (2025). Tuning Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Hydrophilization and Coating Stability via the Optimization of Polyethylene Glycol Molecular Weight. Polymers, 17(24), 3296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243296