Mechanism of Interfacial Slippage in the Micro-Triangle and Composite Fiber Membrane Characteristics in Rotary-Force Spinning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Mechanism of Micro-Triangle Slip in Rotational-Force Spinning

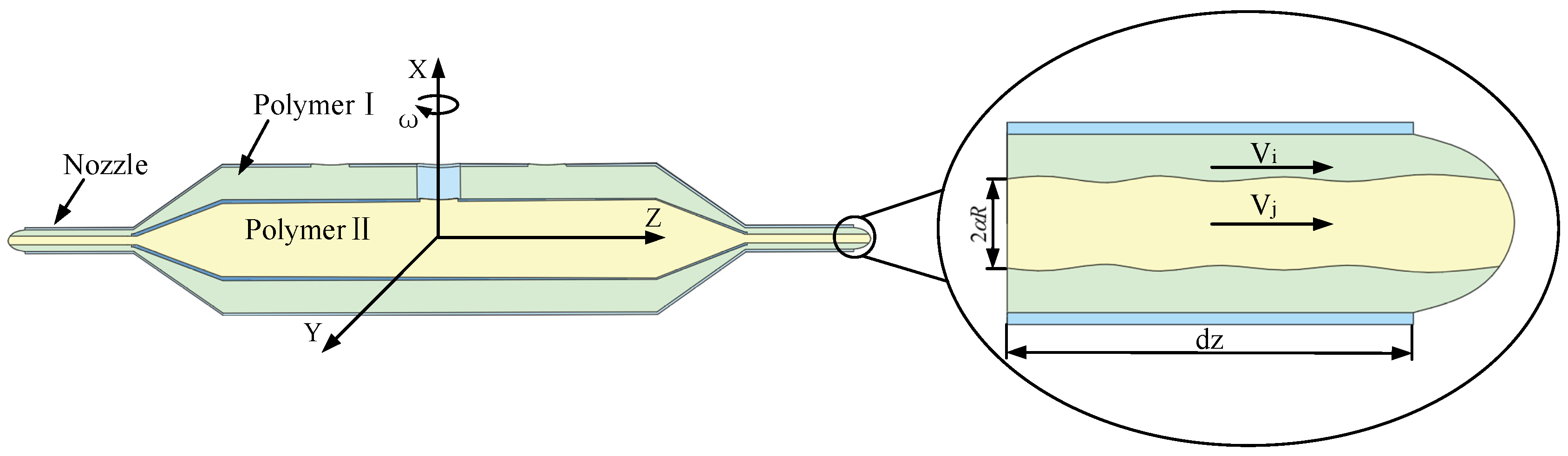

2.1. Formation Model of Micro-Triangle

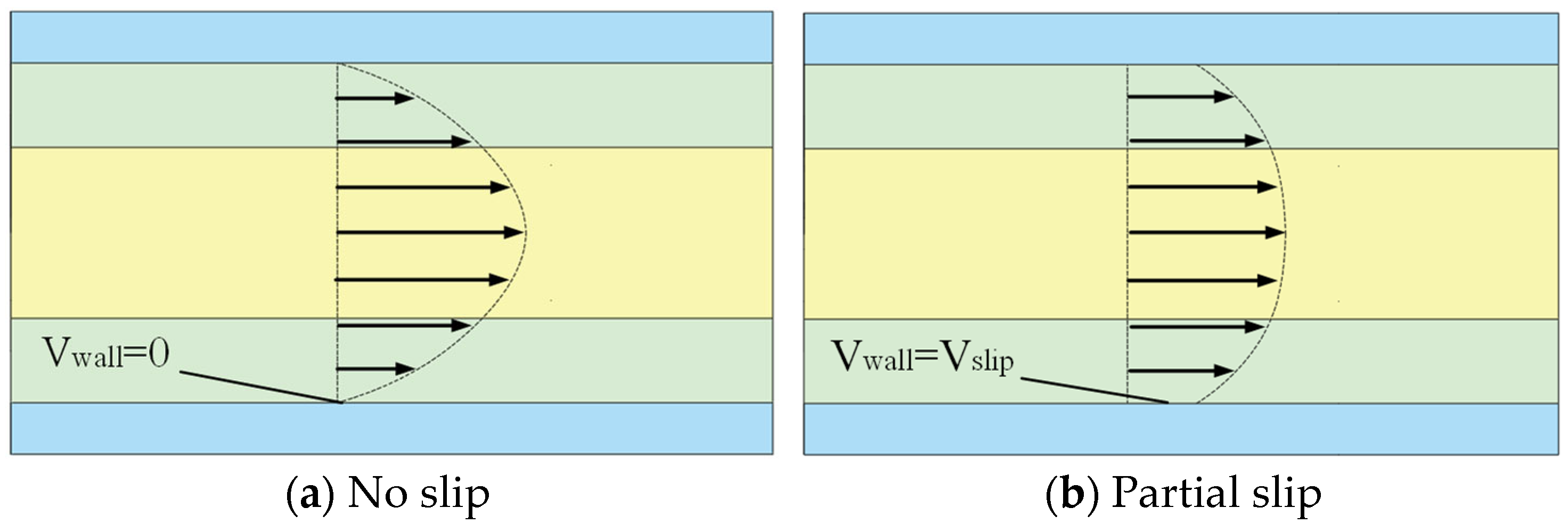

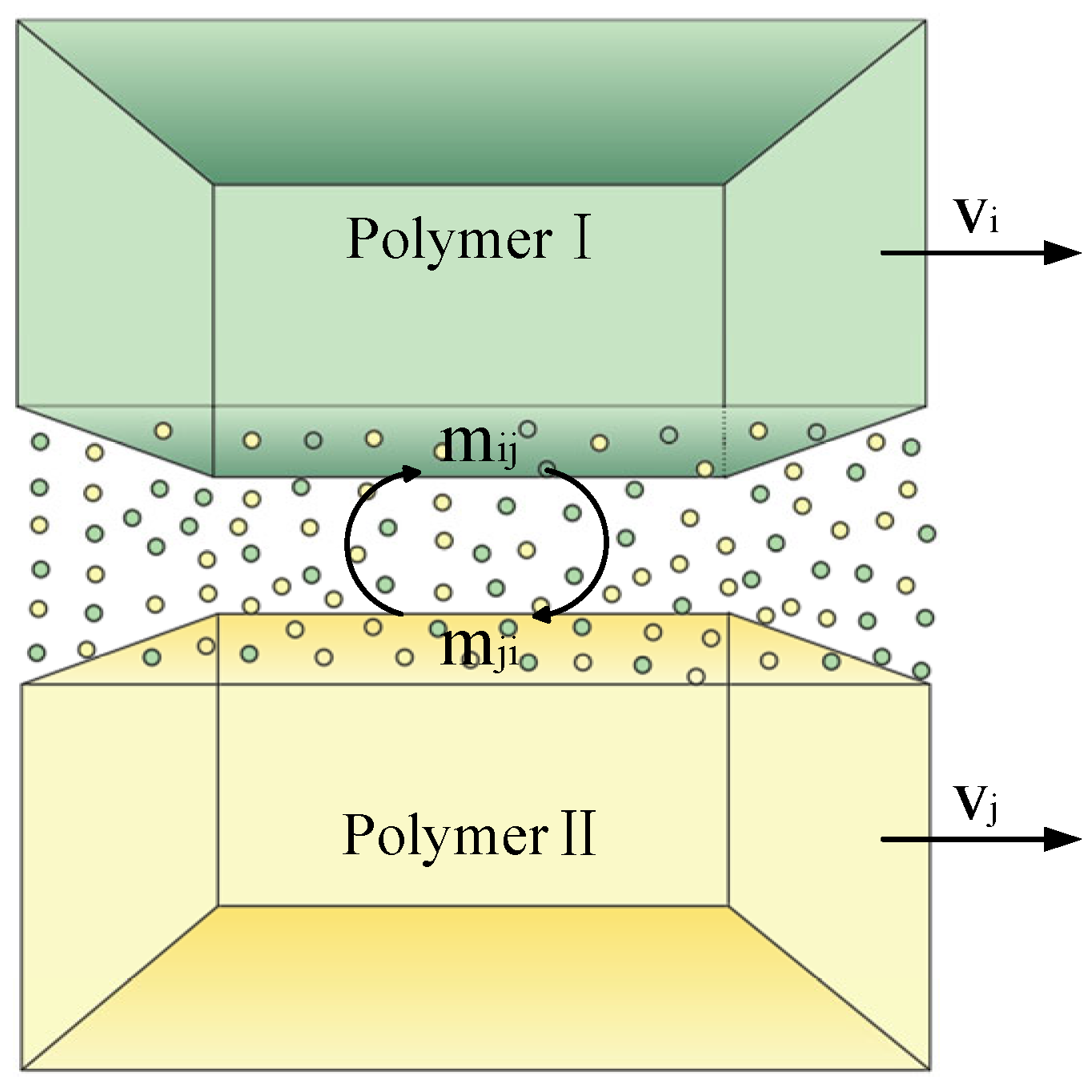

2.2. Micro-Triangle Liquid–Liquid Slip Model

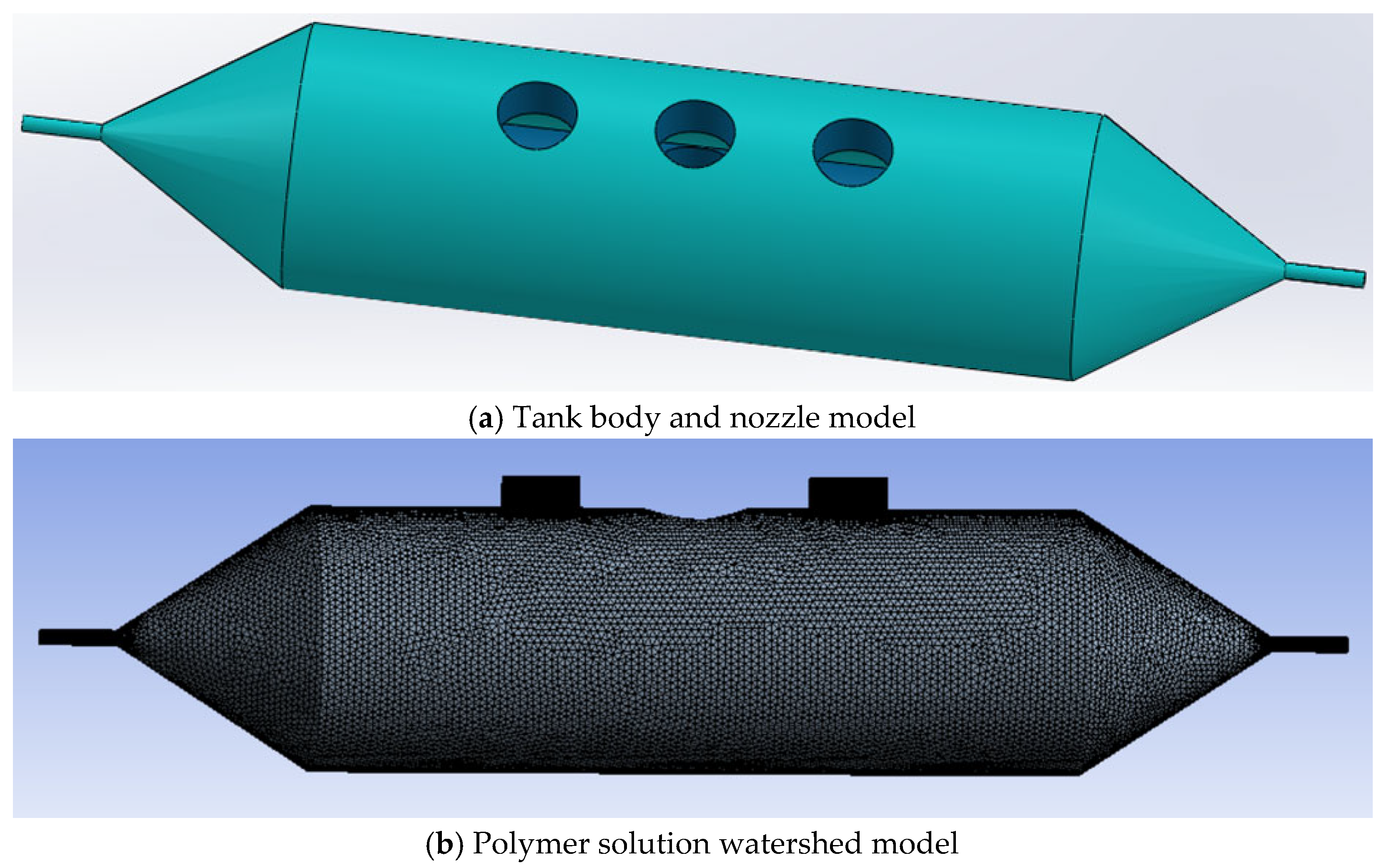

3. Simulation and Analysis of Micro-Triangle Slip Phenomenon

4. Experiment on the Preparation of Composite Fiber Membranes by Rotational-Force Spinning Technology

4.1. Mechanical Analysis of Peo/Hec Composite Fiber Membranes

4.2. Thermal Stability Analysis of Peo/Hec Composite Fiber Membranes

4.3. The Influence of Polymer Solution Concentration on the Morphology of Composite Fibers

4.4. The Influence of Rotational Speed on the Morphology of Composite Fibers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Meng, W.; Zhang, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, F.; Shang, Y.; Cao, A. Systematic design of MXene/thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube@polypyrrole fiber electrodes for efficient flexible fiber supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 682, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, E.H.; Baek, J.H.; Woo, K.M. Targeting Age-Related Impaired Bone Healing: ZnO Nanoparticle-Infused Composite Fibers Modulate Excessive NETosis and Prolonged Inflammation in Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Han, L.; Hou, Y.; Qiao, X.; Zhu, M. P3HT/g-C3N4 composite fiber membranes for high-performance photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 682, 161673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yin, J.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Preparation of PA6-PVA composite fiber membrane based on coaxial spinning method and wettability study. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Dong, W.; Li, X.; Chen, X. A novel dual-mode paper fiber sensor based on laser-induced graphene and porous salt-ion for monitoring humidity and pressure of human. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 158184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazani, Y.; Rafiee, E.; Samadi, A. Development of an efficient, lead-free piezoelectric nanogenerator utilizing PVDF: MnO2–Bi2WO6: RGO composite fiber for self-powered sensing and biomechanical energy harvesting. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 329, 130136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B. Study on the preparation of side-by-side micro-nano composite fibers by centrifugal spinning based on improved spinneret cavity structure. Polymer 2025, 320, 128077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Qiao, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F. Core–shell nanofibers/polyurethane composites obtained through electrospinning for ultra-broadband electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Kobayashi, H.; Tanaka, K.; Takarada, W.; Kikutani, T.; Takasaki, M. Stereocomplex crystal formation in sheath/core and sea/island Poly(l-lactic acid)/poly(d-lactic acid) fibers prepared through laser-heated melt electrospinning and subsequent annealing processes. Polymer 2025, 317, 127889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajra, G.; Brunčko, M.; Gusel, L.; Anžel, I. Comparative analysis of a 3D printed polymer bonded magnet composed of a TPU-PA12 matrix and Nd-Fe-B atomised powder and melt spun flakes respectively. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 34, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Chen, S.; Jerrams, S.; Zhou, F.-L.; Zhou, Y. A novel stretchable composite fiber for strain and magnetic sensors and actuators: The application of polystyrene-ethylene-butylene-styrene/carbon Nanotubes with encapsulated magnetorheological fluid. Compos. Commun. 2025, 53, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R.; Citarrella, M.C. Stable and reusable electrospun bio-composite fibrous membranes based on PLA and natural fillers for air filtration applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 42, e01146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, L. A coalescing filter with hybrid structure of oleophilic/oleophobic media by centrifugal spinning. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359 Pt 1, 130512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, Y. Centrifugal Spinning: An Alternative Approach to Fabricate Nanofibers at High Speed and Low Cost. Polym. Rev. 2014, 54, 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Lai, Z.; Wang, J.; Duan, Y. Spinning solution flow model in the nozzle and experimental study of nanofibers fabrication via high speed centrifugal spinning. Polymer 2020, 205, 122794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanheusden, C.; Vanminsel, J.; Reddy, N.; Samyn, P.; D’Haen, J.; Peeters, R.; Ethirajan, A.; Buntinx, M. Fabrication of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) Fibers Using Centrifugal Fiber Spinning: Structure, Properties and Application Potential. Polymers 2023, 15, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, Q. Investigation of PEO/HEC Composite Fiber Fabrication and Liquid-Wall Slip Behavior in Rotary Force Spinning. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Hong, D.; Ye, P.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Q. Mechanism and experimental investigation on the formation of micro-triangle stepped jet in composite spinning solution. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 4309–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, Q.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Q. Jet slipping mechanism and fabricating of composite fiber by multiple field coupling. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhou, K.; Chen, X.; Hao, H.; Huang, Y. Preparation of Porous TiO2/PVDF/CA Fibers for Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes by Centrifugal Spinning. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.; Astrid Yáñez-Hernández, L.; Lozano, K.; Padilla-Gainza, V.M.; Alejandro Lozano-Morales, S. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using PMMA/TiO2 nanoparticles composites fibers obtained through centrifugal spinning. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 21, 4611–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Rao, J.; et al. Facile preparation of biocompatible and antibacterial water-soluble films using polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl chitosan blend fibers via centrifugal spinning. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 317, 121062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary, S.A.; Ariram, N.; Gopinath, A.; Chinnaiyan, S.K.; Raja, I.S.; Sahu, B.; Dev, V.R.G.; Han, D.-W.; Madhan, B. Investigation on Centrifugally Spun Fibrous PCL/3-Methyl Mannoside Mats for Wound Healing Application. Polymers 2023, 15, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramzan, M.; Shahryar, M.; Abbas, S.; Amir, M.; Saydaxmetova, S.R.; Jan, R.; Al Agha, A.; AL Garalleh, H. Heat transfer with magnetic force and slip velocity on non-Newtonian fluid flow through a porous medium. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 2025, 13, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, D.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Gan, Y.; Zheng, S. The role of wall slip and temperature in shield tail seal performance: A novel modeling approach. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2025, 157, 106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qi, F. Study on the deterioration of bond-slip performance of rockbolt grouted structures under corrosion. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 179, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrihieli, H.; Aldhabani, M.S. Analysis of dissipative slip flow in couple stress nanofluids over a permeable stretching surface for heat and mass transfer optimization. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 67, 105819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poesio, P.; Damone, A.; Matar, O.K. A multiscale approach to interpret and predict the apparent slip velocity at liquid-liquid interfaces. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 923, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q. High-Speed Centrifugal Spinning Polymer Slip Mechanism and PEO/PVA Composite Fiber Preparation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Schossig, J.; Towolawi, A.; Xu, K.; Bayiha, E.; Mohanakanthan, M.; Savastano, D.; Jayaraman, D.; Zhang, C.; Lu, P. High-Speed Electrospinning of Ethyl Cellulose Nanofibers via Taylor Cone Optimization. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2024, 2, 2454–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Sarma, S. Taylor cone height as a tool to understand properties of electrospun PVDF nanofibers. J. Electrost. 2022, 120, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, D.J.; Huang, D.M. The Effect of Hydrodynamic Slip on Membrane-Based Salinity-Gradient-Driven Energy Harvesting. Langmuir 2016, 32, 3420–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Weihs, F.G.; Fletcher, D. CFD study of the effect of unsteady slip velocity waveform on shear stress in membrane systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 192, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 4 wt.%HEC | 5 wt.%HEC | 4 wt.%PEO | 5 wt.% PEO | 6 wt.% PEO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | 6.800 | 17.839 | 1.750 | 4.096 | 11.066 |

| n | 0.637 | 0.568 | 0.729 | 0.661 | 0.571 |

| Sample | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strain (%) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P4-H5-1800 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 141.62 ± 2.4 | 1.21 ± 0.5 |

| P5-H5-1800 | 1.02 ± 0.03 | 127.278 ± 1.18 | 6.04 ± 0.24 |

| P6-H5-1800 | 0.71 ± 0.07 | 88.60 ± 0.88 | 4.61 ± 1.21 |

| P6-H4-900 | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 316.89 ± 1.05 | 1.27 ± 2.13 |

| P6-H4-1200 | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 371.18 ± 2.17 | 1.82 ± 1.05 |

| P6-H4-1500 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 421.40 ± 1.51 | 5.37 ± 0.73 |

| P6-H4-1800 | 1.82 ± 0.03 | 155.68 ± 3.04 | 8.22 ± 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ji, Q. Mechanism of Interfacial Slippage in the Micro-Triangle and Composite Fiber Membrane Characteristics in Rotary-Force Spinning. Polymers 2025, 17, 3235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233235

Ma J, Zhang M, Zhao S, Zhang Z, Chen Z, Ji Q. Mechanism of Interfacial Slippage in the Micro-Triangle and Composite Fiber Membrane Characteristics in Rotary-Force Spinning. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233235

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Jianwei, Meng Zhang, Shuo Zhao, Zhiming Zhang, Zhen Chen, and Qiaoling Ji. 2025. "Mechanism of Interfacial Slippage in the Micro-Triangle and Composite Fiber Membrane Characteristics in Rotary-Force Spinning" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233235

APA StyleMa, J., Zhang, M., Zhao, S., Zhang, Z., Chen, Z., & Ji, Q. (2025). Mechanism of Interfacial Slippage in the Micro-Triangle and Composite Fiber Membrane Characteristics in Rotary-Force Spinning. Polymers, 17(23), 3235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233235