Abiotic Degradation Technologies to Promote Bio-Valorization of Bioplastics

Abstract

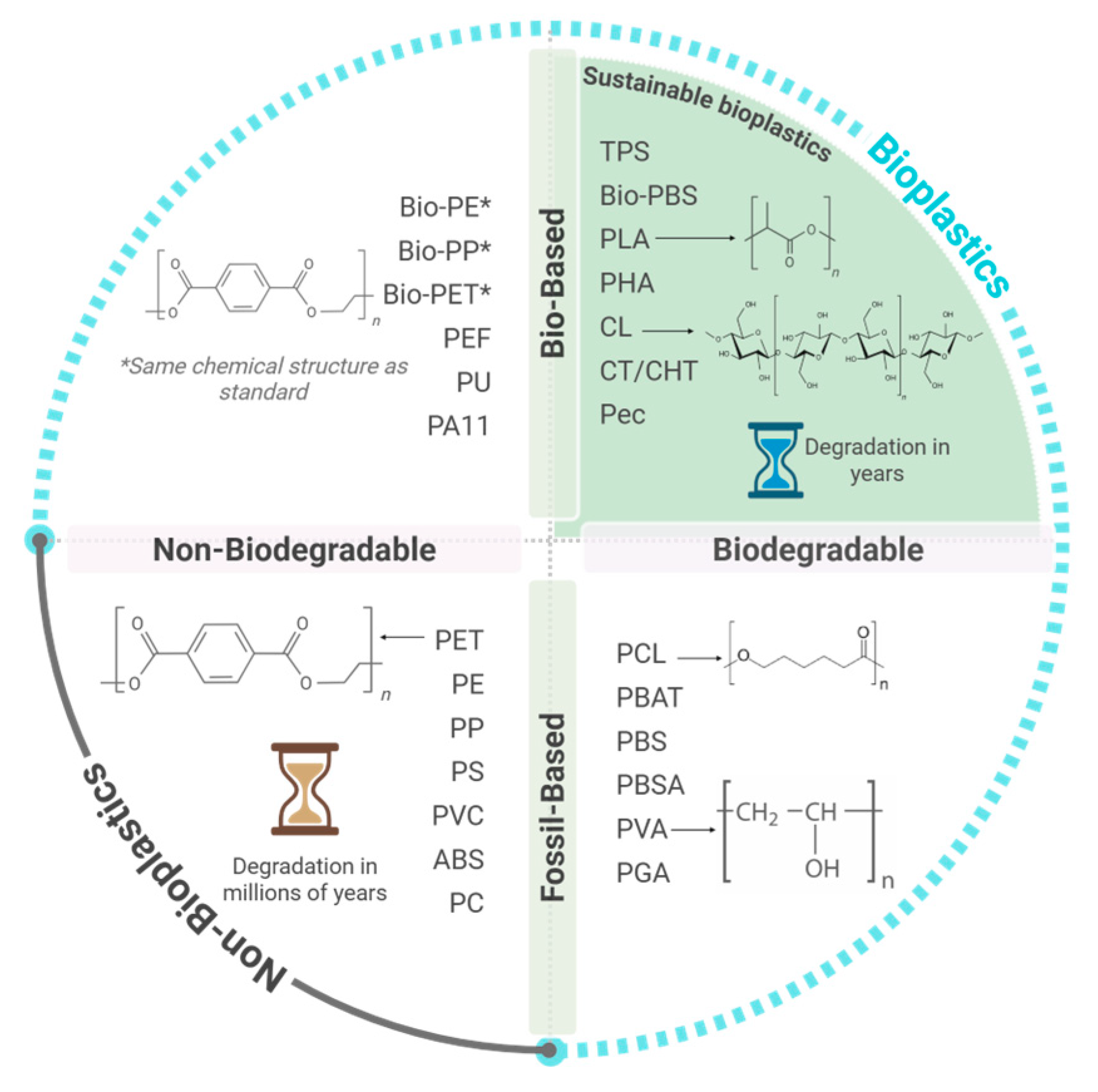

1. Overview of Bioplastics: Concepts and Properties

2. Bio-Valorization of Biodegradable Bioplastics

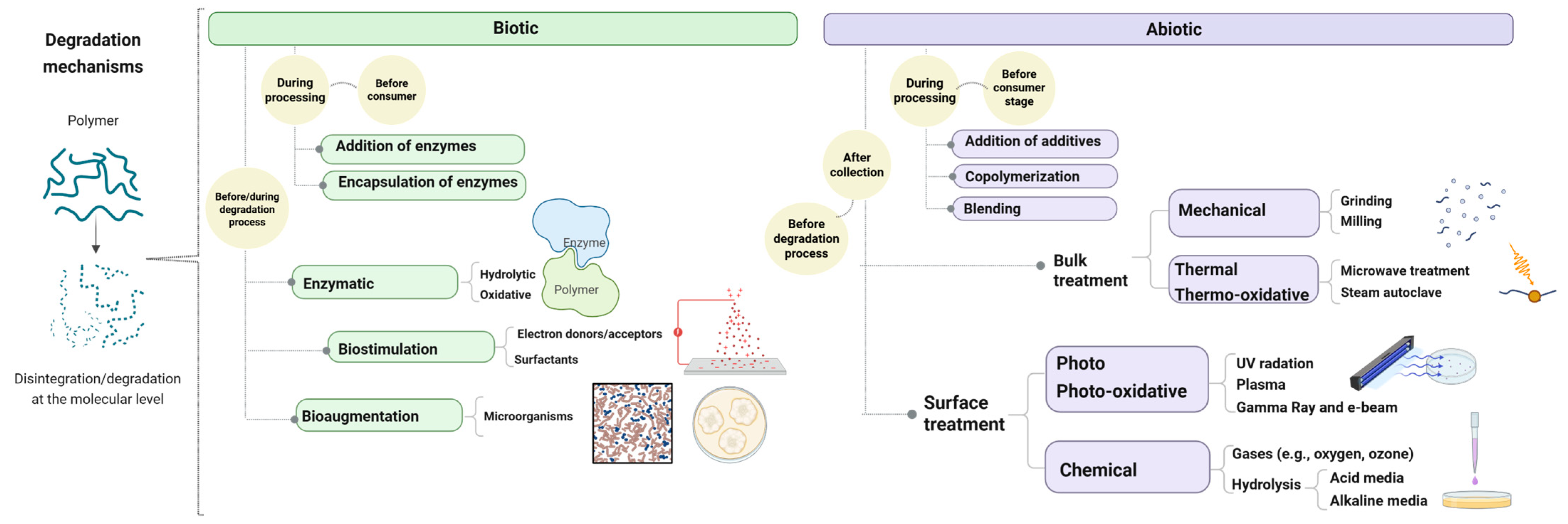

2.1. Degradation of Bioplastics

2.2. Biodegradation Strategies for Bioplastics

- (1)

- Abiotic degradation is to a certain extent considered the initial step in the biodegradation process, where external factors such as sunlight, heat, oxygen, and moisture trigger thermal, chemical, mechanical, and photodegradation pathways. This stage weakens the polymer structure, even producing an initial fragmentation [8].

- (2)

- Subsequently, biodeterioration occurs, characterized by the colonization of the polymer surface by microorganisms, thanks to biofilm formation. The microorganism initially attaches to the polymer surface via the cell pole or flagellum, with irreversible attachment happening through a glue-like substance and tail-like structures. This is followed by the secretion of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), which constitute a slimy matrix composed of proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and nucleic acids [56]. EPSs promote the formation of multicellular clusters that maintain close contact with both the substrate and neighboring cells, establishing a stable biofilm that may support subsequent enzymatic activity and biodegradation under favorable conditions.

- (3)

- As polymers are insoluble and too large for direct microbial uptake, extracellular enzymatic activity is essential in the depolymerization stage [57]. Microorganisms secrete extracellular enzymes that cleave the chemical bonds within polymer chains. These enzymes act as biological catalysts, significantly accelerating reactions that would otherwise proceed very slowly, even for bioplastics derived from renewable resources, such as PLA and PHAs [58]. The potential of purified enzymes, such as lipases, cutinases, and proteinase K, has been extensively studied [59,60], particularly in controlled systems, where they have demonstrated high efficiency in catalyzing the cleavage of ester bonds in bio-polyesters. This enzymatic depolymerization transforms high-molar mass macromolecules into smaller units as oligomers, dimers, and monomers [58,61].

- (4)

- Monomers surrounding the microbial cells pass through the cellular membrane to be bioassimilated. Their uptake can occur easily thanks to passive diffusion [62] or through specific membrane carriers [51]. Monomers that cannot easily be transported into cells can undergo biotransformation reactions, giving intermediate compounds that may or may not be further assimilated [51].

- (5)

- Once the transported monomers are inside cells, they are oxidized to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through three mechanisms: aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration, and fermentation, depending on microbial capacities to grow in the presence or absence of oxygen. As a result of catabolic activity, monomers are mineralized into CO2, methane, nitrogen, and water [63].

2.3. Standards for Aerobic and Anaerobic Biodegradation and Disintegration Testing

- EN 13432: In the European marketplace, a packaging product must meet these minimum requirements to be marketable as compostable and thus be processed by industrial composting during end of life [69]: disintegration of ≥90% of the mass that passes through a 2 mm sieve after 12 weeks, biodegradation of ≥90% of the organic carbon to be mineralized into CO2 within ≤6 months, absence of negative effects on the composting process, and heavy metal quantities below the given maximum values (absence of ecotoxicological effects) [70].

- ASTM D6400: This contains the framework for the United States of America and specifies a minimum of 60% biodegradation for heteropolymers and 90% for homopolymers within 180 days at ≥60 °C to be certified as compostable. The test method is equivalent to ISO 17088 [71].

- ISO 17088: This distinguishes requirements for labelling plastic products as biodegradable during composting, compostable, or compostable in municipal and industrial composting facilities. For the compostable requirements, it demands that 90% of the organic carbon is converted to CO2 within 180 days, relative to a cellulose reference. As well as EN 13432, ISO 17088 does not strictly specify conditions, though it states that composting must be developed in well-managed industrial composting processes [72]. However, this standard refers to the typical tests applied by ISO 14855, where biopolymers classified as compostable must biodegrade at thermophilic conditions (58 ± 2 °C) at 55% relative humidity [73].

2.4. Factors Affecting Bioplastic Biodegradation

2.4.1. Factors Inherent to the Polymer

2.4.2. External Factors

- −

- At temperatures below Tg, physical aging occurs, characterized by molecular rearrangement without chemical degradation.

- −

- In the range between Tg and Tm, dimensional stability is compromised and phenomena such as shape loss, recrystallization, and thermal decomposition of low-molar mass additives can be observed.

- −

- When the temperature exceeds Tm, loss of structure of the crystalline region happens, leading to a disorganized melt and collapse of the polymer structure.

- −

- At temperatures above the decomposition temperature (Td), combustion takes place and the energy stored by the material may be recovered in heat form.

2.5. Evidence of Biopolymer Degradation

2.5.1. Macroscopic Variations

2.5.2. Microscopic Morphology and Surface Properties

2.5.3. Thermal Properties and Crystalline Structure

2.5.4. Chemical Structure

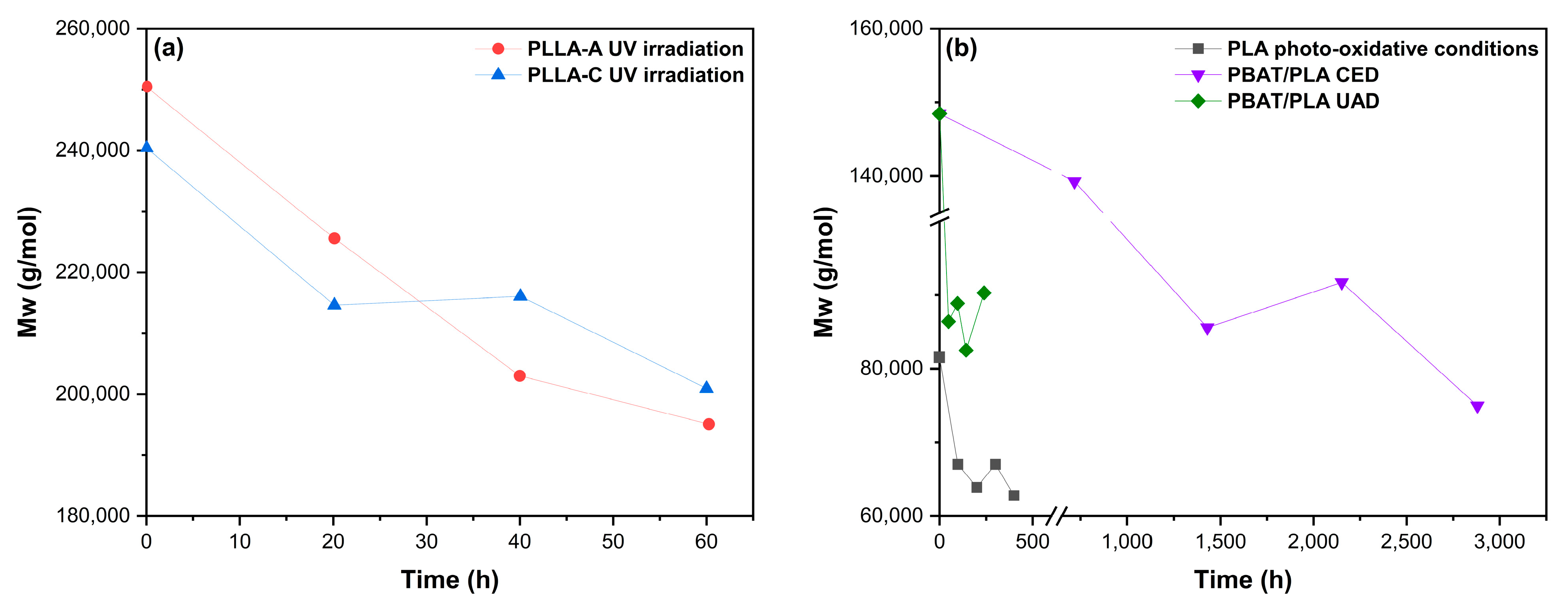

2.5.5. Molar Mass

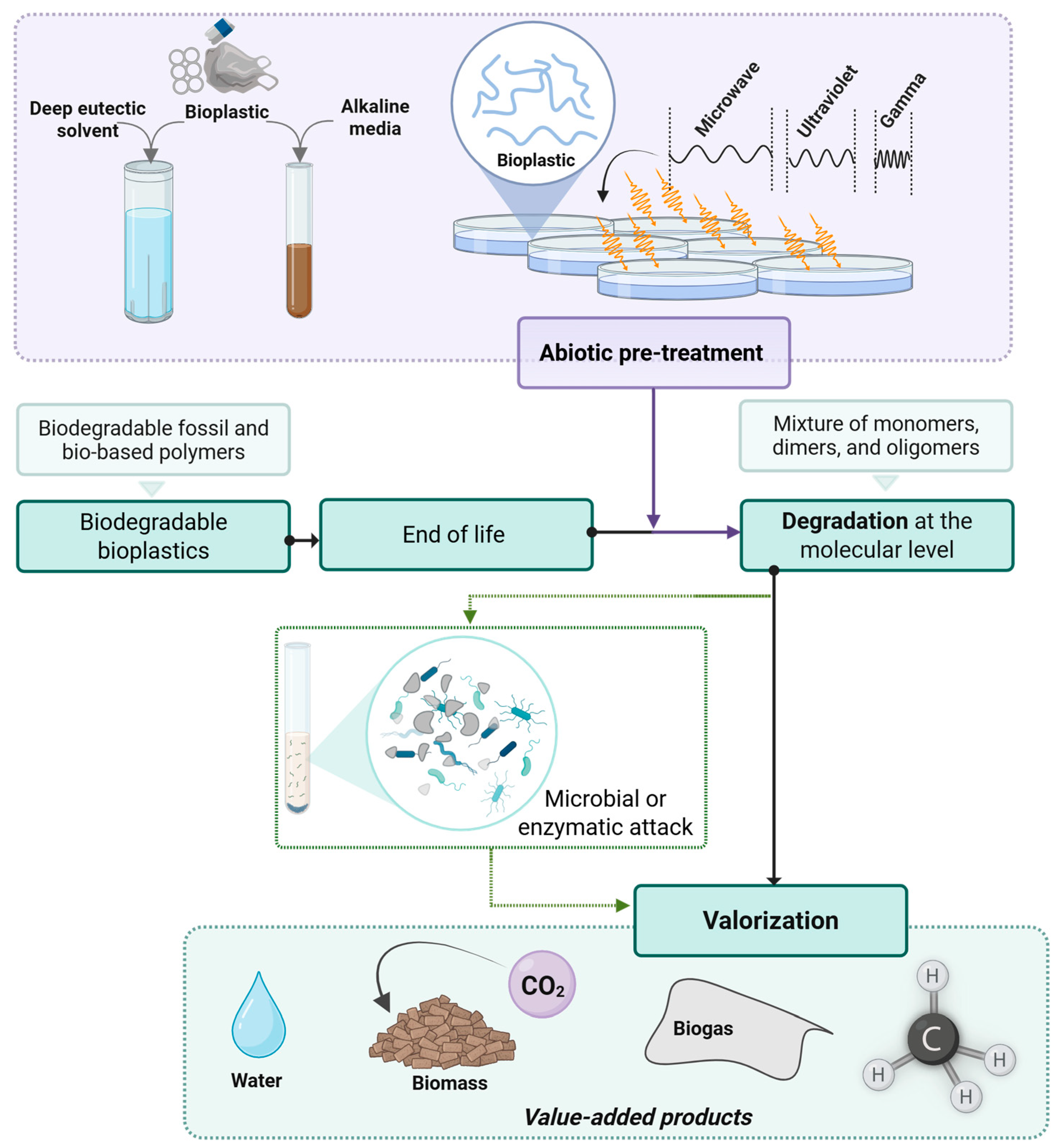

2.6. Strategies to Promote Bio-Valorization of Bioplastics

3. Abiotic Strategies and Their Integration into Bioplastic Bio-Valorization Value Chains

3.1. Physical-Based Treatments

3.1.1. Thermal Pretreatment

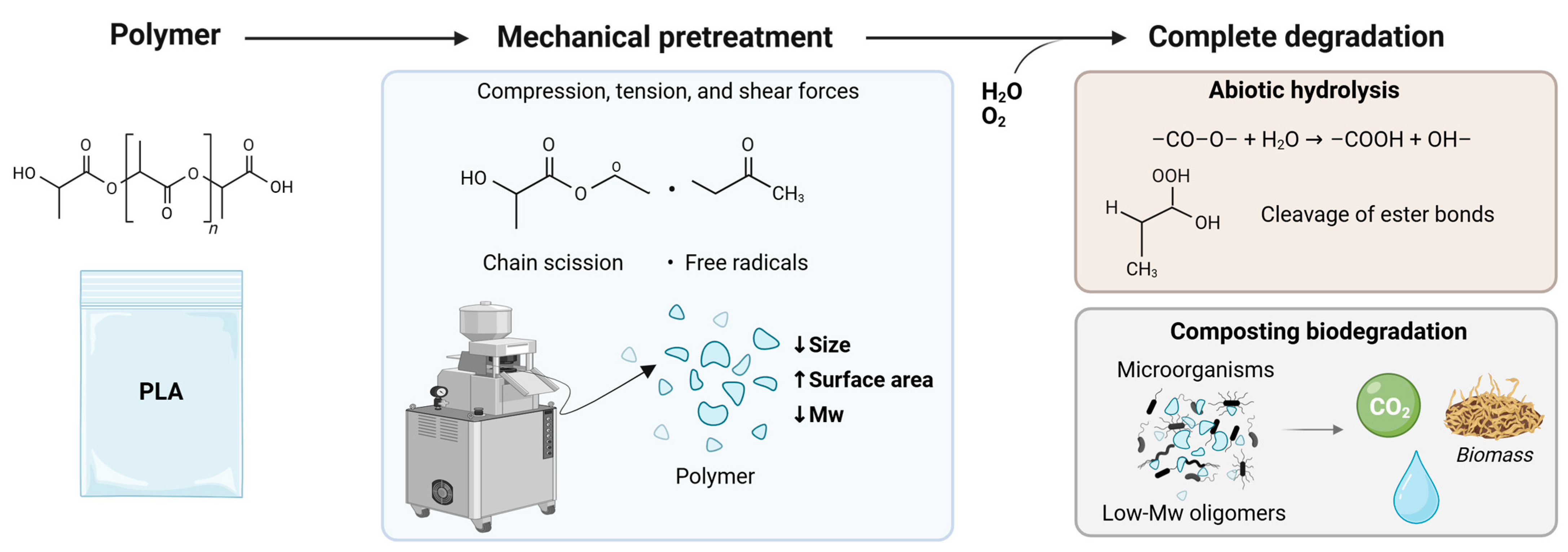

3.1.2. Mechanical Pretreatment

3.1.3. UV Pretreatment

3.1.4. Ionizing Radiation Pretreatments

3.1.5. Plasma Treatment

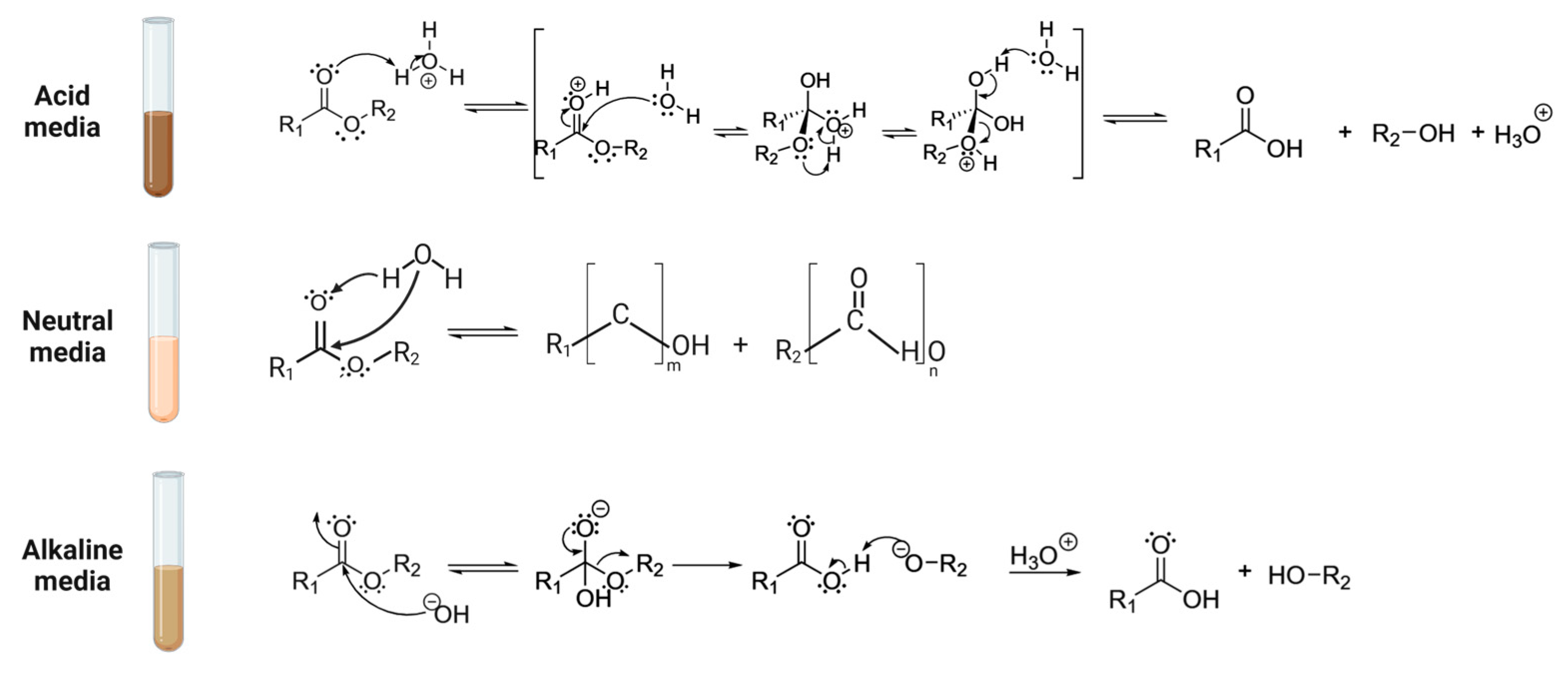

3.2. Chemical-Based Pretreatments

3.2.1. Hydrolytic Approaches

3.2.2. Non-Oxidative Solvolytic Strategies

3.2.3. Oxidative Pretreatment

3.3. Monitoring Degradation and Technical Implications for Abiotic Pretreatments

| Evidence of Degradation | Key Indicators | Pretreatments Technologies | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Chemical | ||||||||

| Thermal | Mechanical | UV | Plasma | Hydrolytic | Non- Oxidative | Oxidative | |||

| Macroscopic appearance | |||||||||

| Gravimetry | ↓ Mass loss | × | × | × | × | × | [99,196] | ||

| Color variation | b* parameter variation | × | × | [100,115] | |||||

| Microscopic morphology and surface properties | |||||||||

| Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) | Structural defects | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | [148,192] |

| Polarized optical microscopy (POM) | Morphology of spherulite variation | × | [102] | ||||||

| Water contact angle (WCA) | Hydrophilic performance variation | × | × | × | × | [131,192] | |||

| Thermal properties and crystalline structure | |||||||||

| Tensile tests (stress, elongation to break) | ↓ σty | × | × | × | × | [102] | |||

| X-ray diffraction (XRD) | Mean size of crystalline domains | × | × | × | × | [199] | |||

| Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) | Tm, Tc, Tg, and Xcr variation | × | × | × | × | × | [99,209] | ||

| Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) | ↓ Tdg ↑ % residue | × | × | × | [200] | ||||

| Chemical structure | |||||||||

| Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) | Variation in carbonyl groups | × | × | × | × | × | × | [120,149,155] | |

| Nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) | Soluble oligomers presence | × | [201,230] | ||||||

| X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) | Oxygen-containing groups (↑ O/C) | × | × | × | [131,193] | ||||

| Molar mass | |||||||||

| Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) | ↓ Mn, Mw | × | × | × | × | × | × | [149,164] | |

| Capillary viscosimetry | ↓ IV | × | [137] | ||||||

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations and Symbols

| AOPs | Advanced Oxidation Processes | PBSA | Poly(butylene succinate)-co-adipate |

| ATBC | Acetyl Tributyl Citrate | PCL | Poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| BC | Bacterial Cellulose | PE | Polyethylene |

| BMP | Biochemical Methane Potential | PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| BMPs | Biodegradable Microplastics | PET | Poly(ethylene terephthalate) |

| CL | Cellulose | Pec | Pectin |

| CT | Chitin | PHAs | Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| CHT | Chitosan | PLA | Poly(lactic) acid |

| DES | Deep Eutectic Solvent | PP | Polypropylene |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry | PS | Polystyrene |

| E | Tensile Modulus | PVA | Poly (vinyl alcohol) |

| εB | Elongation to Break | PVC | Poly(vinyl chloride) |

| EPS | Extracellular Polymeric Substance | SRCs | Self-Reinforced Polymer Composites |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | Td | Decomposition Temperature |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas | Tg | Glass Transition Temperature |

| GPC | Gel Permeation Chromatography | TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| LDPE | Low-Density Polyethylene | Tm | Melting Temperature |

| MCS | Modified Cassava Starch | TPS | Thermoplastic Starch |

| Mn | Number-Average Molar Mass | TS | Tensile Strength |

| MPs | Microplastics | US | Ultrasonication |

| Mw | Weight-Average Molar Mass | UV | Ultraviolet |

| NR | Natural Rubber | VS | Volatile Solids |

| PA | Polyamide | XRD | X-Ray Diffraction Spectroscopy |

| PAAM | Polyacrylamide | XRF | X-Ray Fluorescence |

| PBAT | Poly(butylene adipate)-co-terephthalate | XPS | X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| PBS | Poly(butylene succinate) |

References

- Vert, M.; Doi, Y.; Hellwich, K.H.; Hess, M.; Hodge, P.; Kubisa, P.; Rinaudo, M.; Schué, F. Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012). Pure Appl. Chem. 2012, 84, 377–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastics Europe. The Circular Economy for Plastics—A European Analysis. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Circular_Economy_report_Digital_light_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Shah, A.A.; Hasan, F.; Hameed, A.; Ahmed, S. Biological degradation of plastics: A comprehensive review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, N.; Montazer, Z.; Sharma, P.K.; Levin, D.B. Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Synthetic Plastics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, T. Polymers and the Environment. In Polymer Science; InTech: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Bioplastics Fact Sheet—What are Bioplastics? Available online: https://docs.european-bioplastics.org/publications/fs/EuBP_FS_What_are_bioplastics.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Tokiwa, Y.; Calabia, B.P.; Ugwu, C.U.; Aiba, S. Biodegradability of Plastics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3722–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bátori, V.; Åkesson, D.; Zamani, A.; Taherzadeh, M.J.; Horváth, I.S. Anaerobic degradation of bioplastics: A review. Waste Manag. 2018, 80, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bher, A.; Cho, Y.; Auras, R. Boosting Degradation of Biodegradable Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, 2200769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, G.; Ross, S.; Tighe, B.J. Bioplastics: New Routes, New Products. In Brydson’s Plastics Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bher, A.; Mayekar, P.C.; Auras, R.A.; Schvezov, C.E. Biodegradation of Biodegradable Polymers in Mesophilic Aerobic Environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Y.; Dong, H.; Hou, H. Effects of high starch content on the physicochemical properties of starch/PBAT nanocomposite films prepared by extrusion blowing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 239, 116231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Poyo, C.; Cerisuelo-Ferriols, J.P.; Badia-Valiente, J.D. Influence of Vinyl Acetate-Based and Epoxy-Based Compatibilizers on the Design of TPS/PBAT and TPS/PBAT/PBSA Films. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Yong, H.; Liu, J. Preparation and characterization of antioxidant, antimicrobial and pH-sensitive films based on chitosan, silver nanoparticles and purple corn extract. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 96, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Encarnação, T.; Tavares, R.; Todo Bom, T.; Mateus, A. Bioplastics: Innovation for Green Transition. Polymers 2023, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrañaga, A.; Lizundia, E. A review on the thermomechanical properties and biodegradation behaviour of polyesters. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 121, 109296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, M.; Cicci, A. Production and processing of biodegradable and compostable biomaterials. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 179, pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E. Compostable Polymer Properties and Packaging Applications. In Plastic Films in Food Packaging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Bioplastics Bioplastics Market Development Update 2024. Available online: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/bioplastics-market-development-update-2024/# (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Fast Facts 2024. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2024/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Fast Facts 2023. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2023/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Badia, J.; Strömberg, E.; Karlsson, S.; Ribes-Greus, A. Material valorisation of amorphous polylactide. Influence of thermo-mechanical degradation on the morphology, segmental dynamics, thermal and mechanical performance. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Ribes-Greus, A. Mechanical recycling of polylactide, upgrading trends and combination of valorization techniques. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, N.C.; Major, I.; Devine, D.; Brennan-Fournet, M.; Pezzoli, R.; Farshbaf-Taghinezhad, S.; Hesabi, M. Multiple recycling of a PLA/PHB biopolymer blend for sustainable packaging applications: Rheology-morphology, thermal, and mechanical performance analysis. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedieu, I.; Aouf, C.; Gaucel, S.; Peyron, S. Mechanical recyclability of biodegradable polymers used for food packaging: Case study of polyhydroxybutyrate-co-valerate (PHBV) plastic. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2022, 39, 1878–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Strömberg, E.; Karlsson, S.; Ribes-Greus, A. The role of crystalline, mobile amorphous and rigid amorphous fractions in the performance of recycled poly (ethylene terephthalate) (PET). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badía, J.; Vilaplana, F.; Karlsson, S.; Ribes-Greus, A. Thermal analysis as a quality tool for assessing the influence of thermo-mechanical degradation on recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate). Polym. Test. 2009, 28, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badía, J.; Strömberg, E.; Ribes-Greus, A.; Karlsson, S. A statistical design of experiments for optimizing the MALDI-TOF-MS sample preparation of polymers. An application in the assessment of the thermo-mechanical degradation mechanisms of poly (ethylene terephthalate). Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 692, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolci, G.; Rigamonti, L.; Grosso, M. The challenges of bioplastics in waste management. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1281–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Depraect, O.; Lebrero, R.; Rodriguez-Vega, S.; Bodel, S.; Santos-Beneit, F.; Martínez-Mendoza, L.J.; Aragão-Börner, R.; Börner, T.; Muñoz, R. Biodegradation of bioplastics under aerobic and anaerobic aqueous conditions: Kinetics, carbon fate and particle size effect. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344 Pt B, 126265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, K.; Kulikowska, D.; Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Zaborowska, M.; Pasieczna-Patkowska, S. Thermophilic and mesophilic biogas production from PLA-based materials: Possibilities and limitations. Waste Manag. 2021, 119, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, M.; Weng, Y. Biodegradation Behavior of Poly (Lactic Acid) (PLA), Poly (Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate) (PBAT), and Their Blends Under Digested Sludge Conditions. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 2784–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, S.V.; Boldrin, A.; Christensen, T.H.; Corami, F.; Daugaard, A.E.; Rosso, B.; Hartmann, N.B. Disintegration of commercial biodegradable plastic products under simulated industrial composting conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brdlík, P.; Borůvka, M.; Běhálek, L.; Lenfeld, P. Biodegradation of Poly(Lactic Acid) Biocomposites under Controlled Composting Conditions and Freshwater Biotope. Polymers 2021, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brdlík, P.; Novák, J.; Borůvka, M.; Běhálek, L.; Lenfeld, P. The Influence of Plasticizers and Accelerated Ageing on Biodegradation of PLA under Controlled Composting Conditions. Polymers 2022, 15, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberti, F.M.; Román-Ramírez, L.A.; Wood, J. Recycling of Bioplastics: Routes and Benefits. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 2551–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.; Mukai, M.; Kubota, K.; Kai, T.; Kaneko, N.; Araki, K.S.; Kubo, M. Degradation of Bioplastics in Soil and Their Degradation Effects on Environmental Microorganisms. J. Agric. Chem. Environ. 2016, 05, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhir, M.A.M.; Zubir, S.A.; Mariatti, J. Effect of different starch contents on physical, morphological, mechanical, barrier, and biodegradation properties of tapioca starch and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blend film. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2023, 34, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja-Blasco, L.; Moriana, R.; Badía, J.; Ribes-Greus, A. Thermal analysis applied to the characterization of degradation in soil of polylactide: I. Calorimetric and viscoelastic analyses. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 2185–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Suzuyoshi, K. Environmental degradation of biodegradable polyesters 2. Poly(ε-caprolactone), poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate], and poly(L-lactide) films in natural dynamic seawater. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 75, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dintcheva, N.T. Overview of polymers and biopolymers degradation and stabilization towards sustainability and materials circularity. Polymer 2024, 306, 127136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Min, J.; Ju, S.; Zeng, X.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Shaheen, S.M.; Bolan, N.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Possible hazards from biodegradation of soil plastic mulch: Increases in microplastics and CO2 emissions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mörtl, M.; Damak, M.; Gulyás, M.; Varga, Z.I.; Fekete, G.; Kurusta, T.; Rácz, A.; Székács, A.; Aleksza, L. Biodegradation Assessment of Bioplastic Carrier Bags Under Industrial-Scale Composting Conditions. Polymers 2024, 16, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.S.; Elsamahy, T.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Zhu, D.; Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Koutra, E.; Metwally, M.A.; Kornaros, M.; Sun, J. Plastic wastes biodegradation: Mechanisms, challenges and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciuffi, B.; Fratini, E.; Rosi, L. Plastic pretreatment: The key for efficient enzymatic and biodegradation processes. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 222, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N.M.; Akkermans, S.; Van Impe, J.F. Enhancing the biodegradation of (bio)plastic through pretreatments: A critical review. Waste Manag. 2022, 150, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thew, X.E.C.; Lo, S.C.; Ramanan, R.N.; Tey, B.T.; Huy, N.D.; Wei, O.C. Enhancing plastic biodegradation process: Strategies and opportunities. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Deng, X.; Jiang, L.; Hao, L.; Shi, Y.; Lyu, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. Current advances, challenges and strategies for enhancing the biodegradation of plastic waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Polymer degradation and stability. In Polymer Science and Nanotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sharma, N. Mechanistic implications of plastic degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, N.; Bienaime, C.; Belloy, C.; Queneudec, M.; Silvestre, F.; Nava-Saucedo, J.-E. Polymer biodegradation: Mechanisms and estimation techniques—A review. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E.; Koter, I.; Skopińska-Wiśniewska, J.; Richert, J. Degradation of polylactide composites under UV irradiation at 254 nm. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2015, 311, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpferich, A. Mechanisms of polymer degradation and erosion. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, N.; Sekhar, V.; Nampoothiri, K.; Pandey, A. 32—Biodegradation of Biopolymers. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijchavengkul, T.; Auras, R. Perspective Compostability of polymers. Polym. Int. 2008, 57, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmouni, M. Enzymatic degradation of cross-linked high amylose starch tablets and its effect on in vitro release of sodium diclofenac. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2001, 51, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V. Microbial Degradation of Synthetic Biopolymers Waste. Polymers 2019, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlioglu, M.; Preziosi, R.; Robson, G.D. Abiotic and biotic environmental degradation of the bioplastic polymer poly(lactic acid): A review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Min, J.; Xue, T.; Jiang, P.; Liu, X.; Peng, R.; Huang, J.W.; Qu, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, N.; et al. Complete bio-degradation of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) via engineered cutinases. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanna, R.; Mahal, Z.; Vieira, E.C.S.; Samavi, M.; Rakshit, S.K. Plastics: Toward a Circular Bioeconomy. In Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquin, J.; Cheng, J.; Odobel, C.; Pandin, C.; Conan, P.; Pujo-Pay, M.; Barbe, V.; Meistertzheim, A.L.; Ghiglione, J.F. Microbial Ecotoxicology of Marine Plastic Debris: A Review on Colonization and Biodegradation by the ‘Plastisphere’. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 424560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanna, R.; Samavi, M.; Rakshit, S.K. Biological degradation of microplastics and nanoplastics in water and wastewater. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Bioplastics FACT SHEET. Recycling and Recovery Options for Bioplastics. Available online: https://docs.european-bioplastics.org/publications/fs/EUBP_FS_End-of-life.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Mohee, R.; Unmar, G.; Mudhoo, A.; Khadoo, P. Biodegradability of biodegradable/degradable plastic materials under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomadolo, N.; Dada, O.E.; Swanepoel, A.; Mokhena, T.; Muniyasamy, S. A Comparative Study on the Aerobic Biodegradation of the Biopolymer Blends of Poly(butylene succinate), Poly(butylene adipate terephthalate) and Poly(lactic acid). Polymers 2022, 14, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, H.-J.; Siebert-Raths, A. Engineering Biopolymers; Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: München, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinaglia, S.; Tosin, M.; Degli-Innocenti, F. Biodegradation rate of biodegradable plastics at molecular level. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 147, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Bioplastics. EN 13432 Certified Bioplastics Performance in Industrial Composting. Available online: https://docs.european-bioplastics.org/publications/bp/EUBP_BP_En_13432.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- UNE-EN 13432:2001; Requirements for Packaging Recoverable Through Composting and Biodegradation. Test Scheme and Evaluation Criteria for the Final Acceptance of Packaging. Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 2001. Available online: https://www.une.org/encuentra-tu-norma/busca-tu-norma/norma?c=N0024465 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ASTM D6400-21; Specification for Labeling of Plastics Designed to be Aerobically Composted in Municipal or Industrial Facilities. American Society for Testing and Materials: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ISO 17088:2021; Organic Recycling—Specifications for Compostable Plastics. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/74994.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 14855:2012; Determination of the Ultimate Aerobic Biodegradability of Plastic Materials Under Controlled Composting Conditions. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/57902.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 20200:2023; Determination of the Degree of Disintegration of Plastic Materials Under Composting Conditions in a Laboratory-Scale Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/81932.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 15985:2014; Determination of the Ultimate Anaerobic Biodegradation Under High-Solids Anaerobic-Digestion Conditions—Method by Analysis of Released Biogas. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/es/contents/data/standard/06/33/63366.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 13975:2019; Determination of the Ultimate Anaerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials in Controlled Slurry Digestion Systems—Method by Measurement of Biogas Production. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/74992.html (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- ISO 14853:2016; Determination of the Ultimate Anaerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials in an Aqueous System—Method by Measurement of Biogas Production. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/67804.html (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Quecholac-Piña, X.; Hernández-Berriel, M.d.C.; Mañón-Salas, M.d.C.; Espinosa-Valdemar, R.M.; Vázquez-Morillas, A. Degradation of Plastics under Anaerobic Conditions: A Short Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazaudehore, G.; Guyoneaud, R.; Lallement, A.; Gassie, C.; Monlau, F. Biochemical methane potential and active microbial communities during anaerobic digestion of biodegradable plastics at different inoculum-substrate ratios. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D6691-17; Standard Test Method for Determining Aerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials in the Marine Environment by a Defined Microbial Consortium or Natural Sea Water Inoculum. American Society for Testing and Materials: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d6691-17.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 14851:2019; Determination of the Ultimate Aerobic Biodegradability of Plastic Materials in an Aqueous Medium—Method by Measuring the Oxygen Demand in a Closed Respirometer. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70026.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 11734:1995; Water quality—Evaluation of the “Ultimate” Anaerobic Biodegradability of Organic Compounds in Digested Sludge—Method by Measurement of the Biogas Production. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/19656.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 17556:2019; Plastics—Determination of the Ultimate aerobic Biodegradability of Plastic Materials in Soil by Measuring the Oxygen Demand in a Respirometer or the Amount of Carbon Dioxide Evolved. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/74993.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Narancic, T.; Verstichel, S.; Reddy-Chaganti, S.; Morales-Gamez, L.; Kenny, S.T.; De Wilde, B.; Babu-Padamati, R.; O’Connor, K.E. Biodegradable Plastic Blends Create New Possibilities for End-of-Life Management of Plastics but They Are Not a Panacea for Plastic Pollution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10441–10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pischedda, A.; Tosin, M.; Degli-Innocenti, F. Biodegradation of plastics in soil: The effect of temperature. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 170, 109017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidurah, S. Methods of Analyses for Biodegradable Polymers: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabek, J.F. Photodegradation of Polymers: Physical Characteristics and Applications, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Gong, H.; Yan, M. Biological Degradation of Plastics and Microplastics: A Recent Perspective on Associated Mechanisms and Influencing Factors. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piemonte, V.; Gironi, F. Kinetics of Hydrolytic Degradation of PLA. J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijchavengkul, T.; Auras, R.; Rubino, M.; Ngouajio, M.; Fernandez, R.T. Assessment of aliphatic–aromatic copolyester biodegradable mulch films. Part II: Laboratory simulated conditions. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, G.; Auras, R.; Singh, S.P. Comparison of the degradability of poly(lactide) packages in composting and ambient exposure conditions. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2007, 20, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidurah, S.; Takada, S.; Shimizu, K.; Ishida, Y.; Yamane, T.; Ohtani, H. Evaluation of biodegradation behavior of poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) with lowered crystallinity by thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation-gas chromatography. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 103, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, C.; Höfft, O.; Gödde, A.; Papadimitriou, N.; Pandis, P.K.; Argirusis, C.; Sourkouni, G. Assessing the Time Dependence of AOPs on the Surface Properties of Polylactic Acid. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, U.; Yamamoto, M.; Seeliger, U.; Müller, R.-J.; Warzelhan, V. Biodegradable Polymeric Materials—Not the Origin but the Chemical Structure Determines Biodegradability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1438–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podzorova, M.V.; Tertyshnaya, Y.V.; Selezneva, L.D.; Popov, A.A. Effect of Environmental Factors on Polylactide–Polybutylene Adipate Terephthalate Composites. Polym. Sci. Ser. D 2024, 17, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ding, J.; Song, X.; Zheng, L.; Huang, J.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z. Aging of poly (lactic acid)/poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blends under different conditions: Environmental concerns on biodegradable plastic. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Yan, Y.; Fan, S.; Min, X.; Wang, L.; You, X.; Jia, X.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Wang, J.; Xu, J. Prediction Model of Photodegradation for PBAT/PLA Mulch Films: Strategy to Fast Evaluate Service Life. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9041–9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Silva, K.; Jordán-Silvestre, A.; Cháfer, A.; Muñoz-Espí, R.; Gil-Castell, O.; Badia, J. Ultrasonic chemo-thermal degradation of commercial poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and thermoplastic starch (TPS) blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 232, 111133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Silva, K.; Capezza, A.J.; Gil-Castell, O.; Badia-Valiente, J.D. UV-C and UV-C/H2O-Induced Abiotic Degradation of Films of Commercial PBAT/TPS Blends. Polymers 2025, 17, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, C.; Cai, F.; Liu, G.; Chen, C. Understanding the mechanism of enhanced anaerobic biodegradation of biodegradable plastics after alkaline pretreatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Echizen, Y.; Nishimura, Y. Photodegradation of biodegradable polyesters: A comprehensive study on poly(l-lactide) and poly(ε-caprolactone). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2006, 91, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashter, S.A. Overview of Biodegradable Polymers. In Introduction to Bioplastics Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Gil-Castell, O.; Ribes-Greus, A. Long-term properties and end-of-life of polymers from renewable resources. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaki, A.; Akakura, N.; Nakasaki, K. Effects of temperature and inoculum on the degradability of poly-ε-caprolactone during composting. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1998, 62, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Castell, O.; Andres-Puche, R.; Dominguez, E.; Verdejo, E.; Monreal, L.; Ribes-Greus, A. Influence of substrate and temperature on the biodegradation of polyester-based materials: Polylactide and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) as model cases. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 180, 109288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rånby, B. Photodegradation and photo-oxidation of synthetic polymers. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1989, 15, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Ao, Z. Review on the abiotic degradation of biodegradable plastic poly(butylene adipate-terephthalate): Mechanisms and main factors of the degradation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, M.F.; Muliana, A.H. Modeling temporal and spatial changes during hydrolytic degradation and erosion in biodegradable polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 180, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codari, F.; Lazzari, S.; Soos, M.; Storti, G.; Morbidelli, M.; Moscatelli, D. Kinetics of the hydrolytic degradation of poly(lactic acid). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 2460–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, P.T.T.; Son, N.T.; Khoi, N.V.; Trang, P.T.; Duc, N.T.; Anh, P.N.; Linh, N.N.; Tung, N.T. Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/thermoplastic canna starch (Canna edulis ker.) (PBAT/TPS) blend film—A novel biodegradable material. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2024, 101, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzari, S.; Codari, F.; Storti, G.; Morbidelli, M.; Moscatelli, D. Modeling the pH-dependent PLA oligomer degradation kinetics. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 110, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H. Hydrolytic Degradation. In Poly(Lactic Acid); Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 467–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. Analytical Methods in UV Degradation and Stabilization Studies. In Handbook of UV Degradation and Stabilization; Wypych, G., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, G.; Cucci, C.; Garcia, O.; Piantanida, G.; Elnaggar, A.; Cassar, M.; Strlič, M. Environmentally induced colour change during natural degradation of selected polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 107, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, F.; Li, C.; Ding, W.; Jin, Y.; Tang, L.; Huang, R. Effect of Starch Plasticization on Morphological, Mechanical, Crystalline, Thermal, and Optical Behavior of Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/Thermoplastic Starch Composite Films. Polymers 2024, 16, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JLudwiczak, J.; Dmitruk, A.; Skwarski, M.; Kaczyński, P.; Makuła, P. UV resistance and biodegradation of PLA-based polymeric blends doped with PBS, PBAT, TPS. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2023, 28, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomez, M.; George, M.; Fabre, P.; Touchaleaume, F.; Cesar, G.; Lajarrige, A.; Gastaldi, E. A comparative study of degradation mechanisms of PHBV and PBSA under laboratory-scale composting conditions. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 167, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMumtaz, T.; Khan, M.; Hassan, M.A. Study of environmental biodegradation of LDPE films in soil using optical and scanning electron microscopy. Micron 2010, 41, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainara, S.; Mistry, A.N.; Malee, C.; Chavananikul, C.; Pinyakong, O.; Assavalapsakul, W.; Jitpraphai, S.M.; Kachenchart, B.; Luepromchai, E. Development of a plastic waste treatment process by combining deep eutectic solvent (DES) pretreatment and bioaugmentation with a plastic-degrading bacterial consortium. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundke, K. Characterization of Polymer Surfaces by Wetting and Electrokinetic Measurements—Contact Angle, Interfacial Tension, Zeta Potential. In Polymer Surfaces and Interfaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 103–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, P.; Messori, M. Surface Modification of Polymers. In Modification of Polymer Properties; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badía, J.; Santonja-Blasco, L.; Moriana, R.; Ribes-Greus, A. Thermal analysis applied to the characterization of degradation in soil of polylactide: II. On the thermal stability and thermal decomposition kinetics. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 2192–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Santonja-Blasco, L.; Martínez-Felipe, A.; Ribes-Greus, A. A methodology to assess the energetic valorization of bio-based polymers from the packaging industry: Pyrolysis of reprocessed polylactide. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 111, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Santonja-Blasco, L.; Martínez-Felipe, A.; Ribes-Greus, A. Reprocessed polylactide: Studies of thermo-oxidative decomposition. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, H. Thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation kinetics and characteristics of poly (lactic acid) and its composites. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.R.A.; Marques, C.S.; Arruda, T.R.; Teixeira, S.C.; de Oliveira, T.V. Biodegradation of Polymers: Stages, Measurement, Standards and Prospects. Macromol 2023, 3, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, S.R.; Karo, W.; Bonesteel, J.; Pearce, E.M. Polymer Synthesis and Characterization: A Laboratory Manual; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780126182408/polymer-synthesis-and-characterization. (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Celina, M.C.; Linde, E.; Martinez, E. Carbonyl Identification and Quantification Uncertainties for Oxidative Polymer Degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 188, 109550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Kaesbach, A.; Beltrán-Sanahuja, A.; Mathers, R.T.; Sanz-Lázaro, C. Understanding the degradation of bio-based polymers across contrasting marine environments using complementary analytical techniques. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 524, 146435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourkouni, G.; Kalogirou, C.; Moritz, P.; Gödde, A.; Pandis, P.K.; Höfft, O.; Vouyiouka, S.; Zorpas, A.A.; Argirusis, C. Study on the influence of advanced treatment processes on the surface properties of polylactic acid for a bio-based circular economy for plastics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, E.; Pereira, T.M.C.; Filgueiras, P.R.; Bueno, M.I.M.S.; de Castro, E.V.R.; Guimarães, R.C.L.; de Sena, G.L.; Rocha, W.F.C.; Romão, W. Monitoring the polyamide 11 degradation by thermal properties and X-ray fluorescence spectrometry allied to chemometric methods. X-Ray Spectrom. 2013, 42, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusa, S. Polymer characterization. In Polymer Science and Nanotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheremisinoff, N.P. Chromatographic Techniques. In Polymer Characterization; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plota, A.; Masek, A. Lifetime Prediction Methods for Degradable Polymeric Materials—A Short Review. Materials 2020, 13, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.H. Analytical Techniques in the Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Santonja-Blasco, L.; Martínez-Felipe, A.; Ribes-Greus, A. Hygrothermal ageing of reprocessed polylactide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, F.; Avolio, R.; Errico, M.E.; Di Pace, E.; Avella, M.; Cocca, M.; Gentile, G. Comparison of biodegradable polyesters degradation behavior in sand. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gao, C.; Sangwan, P.; Yu, L.; Tong, Z. Accelerating the degradation of polyolefins through additives and blending. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 9001–9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.; Strömberg, E.; Kittikorn, T.; Ek, M.; Karlsson, S.; Ribes-Greus, A. Relevant factors for the eco-design of polylactide/sisal biocomposites to control biodegradation in soil in an end-of-life scenario. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 143, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengcheng, H. Life Cycle Eco-design of Biodegradable Packaging Material. Procedia CIRP 2022, 105, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamarche, E.; Massardier, V.; Bayard, R.; Dos Santos, E. A Review to Guide Eco-Design of Reactive Polymer-Based Materials. In Reactive and Functional Polymers Volume Four; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 207–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, M.; Fourati, Y.; Tarrés, Q.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Mutjé, P.; Boufi, S. Blends of PBAT with plasticized starch for packaging applications: Mechanical properties, rheological behaviour and biodegradability. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 144, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Sigdel, A.; Lach, R.; Slouf, M.; Sirc, J.; Katiyar, V.; Bhattarai, D.R.; Adhikari, R. Starch-based biodegradable film with poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate): Preparation, morphology, thermal and biodegradation properties. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2021, 58, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, C.; Barletta, M. Addition of Thermoplastic Starch (TPS) to Binary Blends of Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) with Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT): Extrusion Compounding, Cast Extrusion and Thermoforming of Home Compostable Materials. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 40, 1269–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayekar, P.C.; Limsukon, W.; Bher, A.; Auras, R. Breaking It Down: How Thermoplastic Starch Enhances Poly(lactic acid) Biodegradation in Compost–A Comparative Analysis of Reactive Blends. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 9729–9737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Castell, O.; Badia, J.; Ingles-Mascaros, S.; Teruel-Juanes, R.; Serra, A.; Ribes-Greus, A. Polylactide-based self-reinforced composites biodegradation: Individual and combined influence of temperature, water and compost. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 158, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazaudehore, G.; Guyoneaud, R.; Vasmara, C.; Greuet, P.; Gastaldi, E.; Marchetti, R.; Leonardi, F.; Turon, R.; Monlau, F. Impact of mechanical and thermo-chemical pretreatments to enhance anaerobic digestion of poly(lactic acid). Chemosphere 2022, 297, 133986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morro, A.; Catalina, F.; Sanchez-León, E.; Abrusci, C. Photodegradation and Biodegradation Under Thermophile Conditions of Mulching Films Based on Poly(Butylene Adipate-co-Terephthalate) and Its Blend with Poly(Lactic Acid). J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podzorova, M.V.; Selezneva, L.D.; Tertyshnaya, Y.V. Photodegradation of composites based on polylactide and polybutylene adipate terephthalate. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielichowski, K.; Njuguna, J.; Majka, T.M. Mechanisms of thermal degradation of polymers. In Thermal Degradation of Polymeric Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Cooney, R. Thermal Degradation of Polymer and Polymer Composites. In Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeiarani, J.; Bajwa, D.S.; Rehovsky, C.; Bajwa, S.G.; Vahidi, G. Deterioration in the Physico-Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Biopolymers Due to Reprocessing. Polymers 2019, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husárová, L.; Pekařová, S.; Stloukal, P.; Kucharzcyk, P.; Verney, V.; Commereuc, S.; Ramone, A.; Koutny, M. Identification of important abiotic and biotic factors in the biodegradation of poly(l-lactic acid). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 71, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AJoolaei, A.A.; Makian, M.; Prakash, O.; Im, S.; Kang, S.; Kim, D.-H. Effects of particle size on the pretreatment efficiency and subsequent biogas potential of polylactic acid. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4892-2:2013; Methods of Exposure to Laboratory Light Sources. Part 2: Xenon-Arc Lamps. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/55481.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 4892-3:2024; Methods of Exposure to Laboratory Light Sources. Part 3: Fluorescent UV Lamps. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/83802.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Gil-Castell, O.; Badia, J.; Teruel-Juanes, R.; Rodriguez, I.; Meseguer, F.; Ribes-Greus, A. Novel silicon microparticles to improve sunlight stability of raw polypropylene. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 70, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, W.; Tsutsumi, N. Photodegradation and Radiation Degradation. In Poly(Lactic Acid): Synthesis, Structures, Properties, Processing, and Applications; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M. A review on degradation mechanisms of polylactic acid: Hydrolytic, photodegradative, microbial, and enzymatic degradation. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Echizen, Y.; Nishimura, Y. Enzymatic Degradation of Poly(l-Lactic Acid): Effects of UV Irradiation. J. Polym. Environ. 2006, 14, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardette, M.; Thérias, S.; Gardette, J.-L.; Murariu, M.; Dubois, P. Photooxidation of polylactide/calcium sulphate composites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2011, 96, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; César, K.; Medina, K.; D´ambrosio, R.; Michell, R.M. PLLA and cassava thermoplastic starch blends: Crystalinity, mechanical properties, and UV degradation. J. Polym. Res. 2021, 28, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbachir, S.; Zaïri, F.; Ayoub, G.; Maschke, U.; Naït-Abdelaziz, M.; Gloaguen, J.M.; Benguediab, M.; Lefebvre, J.M. Modelling of photodegradation effect on elastic–viscoplastic behaviour of amorphous polylactic acid films. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2010, 58, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, M.; Bialas, S.; Kaczmarek, H. Effect of nanosilver on the photodegradation of poly(lactic acid). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podzorova, M.V.; Tertyshnaya, Y.V.; Popov, A.A. Hydrolytic degradation of polymer blends based N polylactide and low density polyethylene. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2310, 020258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therias, S.; Larché, J.-F.; Bussière, P.-O.; Gardette, J.-L.; Murariu, M.; Dubois, P. Photochemical behavior of polylactide/ZnO nanocomposite films. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3283–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourkouni, G.; Jeremić, S.; Kalogirou, C.; Höfft, O.; Nenadovic, M.; Jankovic, V.; Rajasekaran, D.; Pandis, P.; Padamati, R.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; et al. Study of PLA pre-treatment, enzymatic and model-compost degradation, and valorization of degradation products to bacterial nanocellulose. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Kim, M.N. Biodegradation of poly(l-lactide) (PLA) exposed to UV irradiation by a mesophilic bacterium. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 85, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanasuttichonlakul, W.; Sombatsompop, N.; Prapagdee, B. Accelerating biodegradation of PLA using microbial consortium from dairy wastewater sludge combined with PLA-degrading bacterium. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 132, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M. Effects of Ionizing Radiation on Biopolymers for Applications as Biomaterials. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2023, 1, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalter, R.; Howarth, D. Gamma Radiation. In Gamma Radiation; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jipa, I.M.; Stroescu, M.; Stoica-Guzun, A.; Dobre, T.; Jinga, S.; Zaharescu, T. Effect of gamma irradiation on biopolymer composite films of poly(vinyl alcohol) and bacterial cellulose. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2012, 278, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masry, W.A.; Haider, S.; Mahmood, A.; Khan, M.; Adil, S.F.; Siddiqui, M.R.H. Evaluation of the Thermal and Morphological Properties of γ-Irradiated Chitosan-Glycerol-Based Polymeric Films. Processes 2021, 9, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karzmark, C.J. Radiological Safety Aspects of the Operation of Electron Linear Accelerators. Med. Phys. 1980, 7, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karzmark, C.J.; Pering, N.C. Electron linear accelerators for radiation therapy: History, principles and contemporary developments. Phys. Med. Biol. 1973, 18, 321–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.F.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Lugão, A.B. Use of gamma-irradiation technology in the manufacture of biopolymer-based packaging films for shelf-stable foods. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2005, 236, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, R.; Sayed, A.; El-Sayed, I.E.; Mahmoud, G.A. Optimizing pectin-based biofilm properties for food packaging via E-beam irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 229, 112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbettaïeb, N.; Karbowiak, T.; Brachais, C.-H.; Debeaufort, F. Impact of electron beam irradiation on fish gelatin film properties. Food Chem. 2016, 195, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyathiar, P.; Selke, S.; Auras, R. The Effect of Gamma and Electron Beam Irradiation on the Biodegradability of PLA Films. J. Polym. Environ. 2016, 24, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, N.; Zarges, J.-C.; Heim, H.-P. Influence of ethylene oxide and gamma irradiation sterilization processes on the degradation behaviour of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) in the course of artificially accelerated aging. Polym. Test. 2024, 132, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimončicová, J.; Kryštofová, S.; Medvecká, V.; Ďurišová, K.; Kaliňáková, B. Technical applications of plasma treatments: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5117–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hou, D.; Luo, Y.; Kaiqi, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Cai, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Degradation of particulate matter utilizing non-thermal plasma: Evolution laws of morphological micro-nanostructure and elemental occurrence state. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Yokochi, A.; Jovanovic, G.; Zhang, S.; von Jouanne, A. Application-oriented non-thermal plasma in chemical reaction engineering: A review. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltech Engineers Pvt. Ltd. Corona Treater System What is a Corona Treater? Available online: https://www.eltech.in/corona-treater-system.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Betton, E.S.; Martin, G.D.; Hutchings, I.M. The Effects of Corona Treatment on Impact and Spreading of Ink-jet Drops on a Polymeric Film Substrate. NIP Digit. Fabr. Conf. 2010, 26, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, T.; Qu, G.; Jia, H.; Zhu, L. Probing the aging processes and mechanisms of microplastic under simulated multiple actions generated by discharge plasma. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Gigli, M.; Costa, M.; Govoni, M.; Seri, P.; Lotti, N.; Giordano, E.; Munari, A.; Gamberini, R.; Rimini, B.; et al. The effect of plasma surface modification on the biodegradation rate and biocompatibility of a poly(butylene succinate)-based copolymer. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 121, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Kim, K.; Chun, S.; Moon, S.Y.; Hong, Y. Plasma-assisted advanced oxidation process by a multi-hole dielectric barrier discharge in water and its application to wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scally, L.; Gulan, M.; Weigang, L.; Cullen, P.J.; Milosavljevic, V. Significance of a Non-Thermal Plasma Treatment on LDPE Biodegradation with Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Materials 2018, 11, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.; Luyt, A.S.; Kasak, P.; Aljarod, O.; Hassan, M.K.; Popelka, A. Effect of plasma treatment on accelerated PLA degradation. Express Polym. Lett. 2021, 15, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Asad, M.; Huo, W.; Shao, Y.; Lu, W. Enhancing degradation of PLA-made rigid biodegradable plastics with non-thermal plasma treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 479, 143985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arolkar, G.; Salgo, M.; Kelkar-Mane, V.; Deshmukh, R. The study of air-plasma treatment on corn starch/poly(ε-caprolactone) films. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 120, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Burkersroda, F.; Schedl, L.; Opferich, A.G. Why degradable polymers undergo surface erosion or bulk erosion. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4221–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorrasi, G.; Pantani, R. Effect of PLA grades and morphologies on hydrolytic degradation at composting temperature: Assessment of structural modification and kinetic parameters. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Castell, O.; Badia, J.D.; Kittikorn, T.; Strömberg, E.; Martínez-Felipe, A.; Ek, M.; Karlsson, S.; Ribes-Greus, A. Hydrothermal ageing of polylactide/sisal biocomposites. Studies of water absorption behaviour and Physico-Chemical performance. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 108, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, L.N.; Grunlan, M.A. Hydrolytic Degradation and Erosion of Polyester Biomaterials. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunioka, M.; Ninomiya, F.; Funabashi, M. Biodegradation of poly(lactic acid) powders proposed as the reference test materials for the international standard of biodegradation evaluation methods. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2006, 91, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Castell, O.; Badia, J.D.; Kittikorn, T.; Strömberg, E.; Ek, M.; Karlsson, S.; Ribes-Greus, A. Impact of hydrothermal ageing on the thermal stability, morphology and viscoelastic performance of PLA/sisal biocomposites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 132, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.H.; Gil-Castell, O.; Cea, J.; Carrasco, J.C.; Ribes-Greus, A. Degradation of Plasticised Poly(lactide) Composites with Nanofibrillated Cellulose in Different Hydrothermal Environments. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 2055–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Peng, W.; Lü, F.; Zhang, H.; Lu, X.; He, P. Impact of the thermo-alkaline pretreatment on the anaerobic digestion of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and poly(lactic acid) (PLA) blended plastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 475, 134882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparella, A.N.; Perrone, S.; Salomone, A.; Messa, F.; Cicco, L.; Capriati, V.; Perna, F.M.; Vitale, P. Use of Deep Eutectic Solvents in Plastic Depolymerization. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeson, P. Pretreatment of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Plastics by UV-C Irradiation, Biosurfactants and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) to Enhance Biodegradation. Master’s Thesis, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, O.A.; Azeem, M.; Nikolaivits, E.; Topakas, E.; Fournet, M.B. Progressing Ultragreen, Energy-Efficient Biobased Depolymerization of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) via Microwave-Assisted Green Deep Eutectic Solvent and Enzymatic Treatment. Polymers 2021, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Feng, J.; Han, R.; Lu, Y.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Li, R. Effect of surfactants on enzymatic hydrolysis of PET. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 134945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhate, C.V.; Srivastava, J.K. Recent advances in ozone-based advanced oxidation processes for treatment of wastewater—A review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Pishbin, E. Ozone-based advanced oxidation processes in water treatment: Recent advances, challenges, and perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 3531–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 1431-3:2017; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Resistance to Ozone Cracking—Part 3: Reference and Alternative Methods for Determining the Ozone Concentration in Laboratory Test Chambers. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70223.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Podzorova, M.; Ivanitskikh, A.; Tertyshnaya, Y.; Khramkova, A. Effect of UV-Irradiation and Ozone Exposure on Thermal and Mechanical Properties of PLA/LDPE Films. In Materials Research Proceedings; Bratan, S., Roschchupkin, S., Eds.; Materials Research Forum LLC: Millersville, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, H.A.; Avinc, O.; Uysal, P.; Wilding, M. The effects of ozone treatment on polylactic acid (PLA) fibres. Text. Res. J. 2011, 81, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyubaeva, P.; Zykova, A.; Podmasteriev, V.; Olkhov, A.; Popov, A.; Iordanskii, A. The Investigation of the Structure and Properties of Ozone-Sterilized Nonwoven Biopolymer Materials for Medical Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyubaeva, P.M.; Zykova, A.; Podmasteriev, V.; Olkhov, A.; Popov, A.; Iordanskii, A. Influence of the ozone treatment on the environmental degradation of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, A.A.; Rakovskii, S.K.; Shopov, D.M.; Ruban, L.V. Mechanism of the reaction of saturated hydrocarbons with ozone. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 1976, 25, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyajan, S.A.; Poolyarat, N. Cassava starch with ozone amendment and its blend: Fabrication and properties for fruit packaging application. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 201, 116886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Vanier, N.L.; Moomand, K.; Pinto, V.Z.; Colussi, R.; da Rosa-Zavareze, E.; Dias, A.R.G. Ozone oxidation of cassava starch in aqueous solution at different pH. Food Chem. 2014, 155, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyajan, S.-A. Robust and biodegradable polymer of cassava starch and modified natural rubber. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAMP. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Global Assessment; IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP (Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection): Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, W.J.; Hong, S.H.; Eo, S. Marine Microplastics: Abundance, Distribution, and Composition. In Microplastic Contamination in Aquatic Environments; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sin, A.; Nam, H.; Park, Y.; Lee, H.; Han, C. Advanced oxidation processes for microplastics degradation: A recent trend. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 9, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandis, P.K.; Kalogirou, C.; Kanellou, E.; Vaitsis, C.; Savvidou, M.G.; Sourkouni, G.; Zorpas, A.A.; Argirusis, C. Key Points of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) for Wastewater, Organic Pollutants and Pharmaceutical Waste Treatment: A Mini Review. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bule-Možar, K.; Miloloža, M.; Martinjak, V.; Cvetnić, M.; Kušić, H.; Bolanča, T.; Kučić-Grgić, D.; Ukić, Š. Potential of Advanced Oxidation as Pretreatment for Microplastics Biodegradation. Separations 2023, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhao, R. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Wastewater Treatment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, I.A.; Alberto, E.A.; Silva-Júnior, A.H.; Macuvele, D.L.P.; Padoin, N.; Soares, C.; Gracher-Riella, H.; Starling, M.C.V.M.; Trovó, A.G. A critical review on microplastics, interaction with organic and inorganic pollutants, impacts and effectiveness of advanced oxidation processes applied for their removal from aqueous matrices. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutkar, P.R.; Gadewar, R.D.; Dhulap, V.P. Recent trends in degradation of microplastics in the environment: A state-of-the-art review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 11, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkham, S.; Pitakpong, A.; Kumar, R. Advanced approaches to microplastic removal in landfill leachate: Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), biodegradation, and membrane filtration. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhou, P.; Yang, Y.; Hall, T.; Nie, G.; Yao, Y.; Duan, X.; Wang, S. Degradation of Microplastics by a Thermal Fenton Reaction. ACS EST Eng. 2022, 2, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NPayanthoth, N.S.; Mut, N.N.N.; Samanta, P.; Li, G.; Jung, J. A review of biodegradation and formation of biodegradable microplastics in soil and freshwater environments. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, P.; Ren, L. Effects of Fe3O4 NMs based Fenton-like reactions on biodegradable plastic bags in compost: New insight into plastisphere community succession, co-composting efficiency and free radical in situ aging theory. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, H.; Almansour, F.H.; Aldhafeeri, Z. Plastic Waste Management: A Review of Existing Life Cycle Assessment Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshoulles, Q.; Gall, M.L.; Benali, S.; Raquez, J.M.; Dreanno, C.; Arhant, M.; Priour, D.; Cerantola, S.; Stoclet, G.; Gac, P.Y. Hydrolytic degradation of biodegradable poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT)—Towards an understanding of microplastics fragmentation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 205, 110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioplastic | Feedstock Nature | Monomer Structure | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | TS (MPa) | E (MPa) | εB (%) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHA’s | Bio-based |  | −30 to 10 | 70 to 170 | 18 to 24 | 700 to 1800 | 3 to 25 | [15,16] |

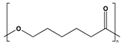

| PBS | Bio-based |  | −40 to −30 | 115 | 35 | 300 to 500 | 560 to 800 | [17,18] |

| PLA | Bio-based |  | 40 to 70 | 130 to 180 | 48 to 53 | 3500 | 30 to 240 | [15] |

| PBAT | Fossil-based |  | −30 | 110 to 115 | 34 to 40 | 2300 to 3300 | 1.2 to 2.5 | [15] |

| PCL | Fossil-based |  | −60 | 59 to 64 | 4 to 28 | 390 to 470 | 700 to 1000 | [15,16] |

| Ref. | Reviewed Polymer | Factors Affecting Degradation | Abiotic Pretreatments | Biotic Pretreatments | Degradation Mechanisms | Degradation Indicators | Pretreatment– Valorization Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | HDPE, LDPE, PP, PET, PS, PU, PVC | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ||

| [47] | HDPE, LDPE, PP, PS, PET, PBS | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | |

| [48] | LDPE, PET, PS, PP, PVC | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | |

| [46] | PE, PP, PS, PBS, PLA, Starch blends | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ |

| [45] | PET, LDPE, HDPE, PP, PC, PUR, PVC, PLA | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | |

| [41] | PLA, PBS | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ | |

| [9] | PLA, PBAT, PCL, PBS, PHB | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Characteristics | Aerobic Biodegradation | Anaerobic Biodegradation |

|---|---|---|

| Electron acceptor | Oxygen | Nitrates, sulfates, or the organic compounds themselves |

| Microorganisms | Aerobic bacteria, fungi | Anaerobic bacteria, archaea |

| Process efficiency and rate | Typically faster due to the high redox potential of oxygen; efficient breakdown of polymers | Slower; limited by the availability of electron acceptors and slower metabolic rates |

| Final degradation products | CO2, H2O, and simpler organic acids | CH4 (in methanogenesis), H2S, and other reduced products |

| Environmental implications | Lower GHG potential; widely used in composting systems | Higher GHG emissions due to methane, applicable to biogas production and anaerobic digesters |

| Common applications | Composting, aerobic soil biodegradation | Anaerobic digestion of organic waste, landfill environments |

| Standard | Tested Environment | Measured Outcome | Conditions | Pass Criteria/ Requirements | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO 14855 | Industrial composting | Mineralization | T: 58 ± 2 °C Oxygen: aerobic RH: 50% CO2 flow rate: 10 mL/min Compost inoculum from municipal solid waste | >90% CO2 vs. microcrystalline cellulose Duration: 180 days Reached plateau | [73] |

| Home composting | Mineralization | T: 28 °C Oxygen: aerobic Compost inoculum from municipal solid waste | >90% CO2 vs. microcrystalline cellulose Duration: 1 year/365 days Reached plateau | ||

| ISO 20200 | Industrial composting | Disintegration | T: 58 ± 2 °C Oxygen: aerobic Compost inoculum from a municipal or industrial aerobic composting plant | 90% of the initial mass passes through a 2 mm sieve Duration: from 45 to 84 days | [74] |

| ISO 15985 | Anaerobic digestion | Mineralization | T: 52 ± 2 °C Oxygen: anaerobic Inoculum from the operating anaerobic digester using high solids charge | Duration: minimum of 15 days Validity of test results: 70% biodegradation of the reference material | [75] |

| Feedstock | Valorization Strategy | Abiotic Suggested Parameters | Key Abiotic Degradation Indicators | Biodegradation Environment | Observation Reported | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | UV irradiation + enzymatic degradation catalyzed with Proteinase K | UV-A light λ: 300–700 nm I: 25.5 mW·cm−2 T: 45 °C RH: 65%, t: 60 h | Reduction in Mn | Enzymatic hydrolysis: T: 37 °C t: 10–60 h pH: 8–8.6 | Accelerated depolymerization after 60 h of irradiation | [161] |

| PLA | UV irradiation + Stenotrophomonas maltophilia LB 2–3 | UV-C light λ: 185–245 nm I: 6.41 × 10−3–3.22 mW·cm−2 t: 24 h | Reduction in Mn, contact angle, and mechanical properties | Compost: T: 37 °C t: 24 h | Biodegradability increased after 8 h of UV-C irradiation, but became more resistant with longer exposure times | [169] |

| PLA | UV irradiation + ultrasonication + enzymatic degradation | UV light t: up to 6 h Ultrasonication 860 kHz | Surface oxidation, increased roughness and porosity | Enzymatic hydrolysis: T: 42 °C t: 8–16 weeks pH: 8.5 | Up to 90% of mass loss after 16 weeks, and the hydrolysate was valorized to bacterial nanocellulose | [168] |

| PLA | UV irradiation + bioaugmentation + dairy wastewater sludge (Pseudomonas geniculata WS3) | UV-A-B-C light λ: 340, 310, and 254 nm t: 150 min T: room temperature | ↑ Brittleness Significant reduction in Mn after 2 h of irradiation ↓Mn/Mw | Soil: T: 58 ± 2 °C RH: 40% pH: 4.3–7.9 Air flow: 25 mL·min−1 | Enhanced weight loss (up to 90% in 12 days) and biodegradation in thermophilic conditions | [170] |

| PBAT/PLA blends | UV aging + microbial biodegradation (Bacillus subtilis) | I: 550 W·m−2, λ: 300–800 nm t: 28 days T: 45 °C | Mw reduction (31%). Carbonyl absorption bands decrease ↑ Roughness | Culture medium: T: 45 °C t: 35 days pH: 7.0 | Biodegradation improved (62%) with a specific bacterial strain (Bacillus subtilis) and UV treatment | [149] |

| PBAT | UV irradiation + microbial biodegradation | UV-A light λ: 320–400 nm t: 336 h I: 1.40 W·m−2·nm | Higher opacity and yellowish color, decrease in TS and ε, higher brittleness, increase in E, reduction in Mw, crosslinking | Compost: t: 45 days | Photodegradation enhanced mineralization, only in the first stages, before crosslinking occurred after advanced irradiation | [90] |

| PLA, TPS, PBS, PBAT PLA/PBS, PLA/PBAT and PLA/TPS blends | UV aging + microbial biodegradation for base materials | Daylight filter and black standard λ: 300–800 nm t: 21 days (6 months simulated conditions) T: 70 °C RH: water spraying | ↑ Loss of color and whitening, especially for blends containing TPS and PBS Visible microcracks ↓ TS up to 87% with high TPS content | Compost: T: 58 ± 2 °C t: 65 days RH: water spraying | Under composting conditions, the neat polymers showed a high degree of disintegration, with TPS degrading the most rapidly | [117] |

| Feedstock | Ionizing Type | Abiotic Suggested Parameters | Key Abiotic Degradation Indicators | Observation Reported | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA/BC | Gamma (γ) irradiation | Source: 137Cs Dose: 20–50 kGy Dose rate: 0.4 kGy/h T: room temperature | ↑ Yellowness/redness FTIR band shifts (-OH, C=O); chain scission at higher doses ↓ Crystallinity | BC is strongly affected by irradiation, confirmed by the splitting of the 1081 cm−1 band. | [173] |

| PHB/PEG | Gamma (γ) irradiation | Source: 60Co Dose: up to 40 kGy Dose rate: 5.72 kGy/h | ↓ WVP (water vapor permeability) at >40 kGy ↓ Crystallinity | Loss of mechanical integrity at 40 kGy, with degradation noticed over 10 kGy. | [177] |

| PEC/PAAm | E-beam Irradiation | Source: E-beam accelerator, 3 MeV, 90 kW. Dose: 5–40 kGy | ↑ Hydrophilicity ↓ Crystallinity Initial crosslinking (<10 kGy) and chain scission (40 kGy) | 30 kGy resulted in optimal mechanical performance and stability, extended shelf-life. | [178] |

| Gelatin/glycerol | E-beam Irradiation | Source: E-beam accelerator, 2.2 MeV Dose: 20–60 kGy Dose rate: 0.3 kGy/s T: room temperature | ↑ Hydrophilicity Crosslinking in the amorphous phase Formation of free radicals over >60 kGy dose | E-beam irradiation improves mechanical (↑ TS up to 30%) and surface functionality. | [179] |

| PLA | Gamma (γ) irradiation | Source: 60Co Dose: 30 kGy Dose rate: 3200 s/kGy T: room temperature | ↓ Mn and Mw Free radical formation | Under simulated composting conditions (ISO 14855-1; 58 °C, for 60–141 days), both gamma- and E-beam-irradiated PLA reached ≥90% mineralization after 6 months of storage. | [180] |

| E-beam Irradiation | Source: E-beam accelerator, 1.5 and 15 mA T: room temperature | ↓ Mn/Mw Slight crosslinking |

| Feedstock | Valorization Strategy | Abiotic Suggested Parameters | Key Abiotic Degradation Indicators | Valorization Environment | Observation Reported | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA (89.5 kDa, 1 mm films) | Corona and RF plasma + accelerated weathering aging | Corona: f: 20.8 kHz t: 1 to 12 s | ↑ Wettability Structural defects (voids, cracks, and cavities) ↑ Roughness ↑ Xc before weathering, especially for RF plasma | UV/weathering aging: ASTM D4329 standard, radiation up to 2000 h | Degradation of PLA was more pronounced with RF than corona plasma pretreatment during weathering aging testing. Increase in hydrolytic degradation. | [191] |

| RF: f: 13.56 MHz t: 15 to 180 s | ||||||

| PLA-based cutlery items: cup strips (CSs) and spoon handles (SHs) | DBD-NTP + composting | V: 55, 75, and 100 V t: 20 and 80 min | ↑ Roughness ↑ Wettability ↑ Carbonyl group index | Home-scale composting reactor: T: 50 ± 5 °C Air flow: 3 L·min−1 | High voltage (HV) accelerated degradation rates, while low voltage and short duration enhanced oxidation. Complete disintegration within 20 days in CSs after HV. | [192] |

| Corn starch–PCL blends (30 µm thickness films) | RF-NTP+ soil | f: 13.56 MHz P: 40 W t: 0.5 to 5 min | ↑ Roughness ↑ Wettability ↑ Mass loss for longer duration times | Soil: Bacillus subtilis MTCC 121. T = 30 °C. RH: 40–50% | Plasma preferentially affects the starch-rich domains within the blend. Modification of surface properties, enhancing adhesion and growth of BS 121. | [193] |

| Feedstock | Valorization Strategy | Abiotic Suggested Parameters | Key Abiotic Degradation Indicators | Biodegradation Environment | Observation Reported | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA PBAT PLA/PBAT/Starch | Thermo-alkaline + anaerobic degradation (wastewater treatment inoculum) | NaOH 1% (w/v) T: 70 °C t: 48 h | Pore structure formation Reduction in Mw | Inoculum substrate ratio: 3 g VS/g VS t: 100 days | Methanogenic rate increases in the initial state, but MPs were found in the digestate. | [201] |

| PLA | Thermo-alkaline + anaerobic degradation | Ca (OH)2 2% (w/v) T: 70 °C t: 48 h | ↑ Roughness Structural defects (voids and cracks) | Inoculum substrate ratio: 2.85 g VS/g VS pH: 7–8 T: 38 °C t: 30 days | Biodegradation yield of 73%. | [148] |

| PET and PLA | DES pretreatment (dip-coating) + bacterial bioaugmentation | DES: choline chloride/glycerol 1:2 molar ratio Dip-coated—1 s Dried—1 h | ↑ Surface wettability↑ Biofilm formation↑ Hydroxyl groups | Bacterial bioaugmentationAqueous mediumPilot-scale composting | DES enhanced microbial adhesion and composting degradation performance. | [120] |

| PLA | UV-C + DES + biosurfactant pretreatment + composting | ChCl/lactic acid (1:2); UV-C up to 8 h; composting 28 days | 68.1% molar mass reduction↑ CO2 evolution | Composting and microbial biodegradation | DES enhanced the hydrophilicity and mineralization rate. | [203] |

| PET | Microwave-assisted DES pretreatment followed by enzymatic hydrolysis | Choline chloride/glycerol/ urea 1:2:1 molar ratio 260 W microwave, 3 min, 20 mL DES volume | 16% monomer recovery↑ Carbonyl index and mass loss | Aqueous enzymatic system (LCC variant ICCG) | DES + microwave-enhanced enzymatic depolymerization. | [204] |

| PET | Anionic surfactants + enzymatic hydrolysis (PETase) | Bicine buffer pH 9.0, 30 °C; 500 nM PETase; surfactants: alkylsulfate, sulfonate, carboxylate | 120× increase in PETase activity, 22% film thickness loss | Buffered aqueous enzymatic hydrolysis (PETase) | Surfactants improved enzyme alignment and activity. | [205] |

| Feedstock | Valorization Strategy | Abiotic Suggested Parameters | Key Degradation Indicators | Valorization Environment | Observation Reported | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHB | Ozone + biodegradation | t: 5 h Ambient conditions T: 24 °C RH: 35% | No impact on crystalline regions ↑ Tensile strength (25 MPa → 42 MPa); slight ↑ elongation at break (1%) | Soil: RH: 60% T: 22 ± 3 °C pH: 6 t: 7, 28, 84, and 168 days | Slower biodegradation (300 days vs. 240 days for pristine PHB). Mass loss, volume loss, and surface defects (craters and cracks) after biodegradation. | [212] |

| Cassava starch (CS) PVA/NR/CS blends | Ozone + biodegradation | t: 50 min Ozone concentration: 20 mg·L−1 T: 50 °C | ↑ Hydroxyl groups ↓Crystallinity ↑ Wettability | Soil: T: 27–28 °C pH: 7 RH: 85% t: 30 days | The biodegradation rate of PVA/NR/CS blends increased in terms of mass loss (100% in 30 days with ≥15% of modified CS). | [214] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez-Silva, K.; Kolcz, N.; Arango, M.C.; Cháfer, A.; Gil-Castell, O.; Badia-Valiente, J.D. Abiotic Degradation Technologies to Promote Bio-Valorization of Bioplastics. Polymers 2025, 17, 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233222

Gutiérrez-Silva K, Kolcz N, Arango MC, Cháfer A, Gil-Castell O, Badia-Valiente JD. Abiotic Degradation Technologies to Promote Bio-Valorization of Bioplastics. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233222