Green Synthesis of Chitosan Silver Nanoparticle Composite Materials: A Comparative Study of Microwave and One-Pot Reduction Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Chitosan Solution

2.2.2. Chitosan-Silver Nanocomposite Synthesis

- A.

- Method 1 (M1): Microwave-assisted reduction method

- B.

- Method 2 (M2): One-pot reduction-based method

2.2.3. Characterization of Chitosan-Silver Nanoparticles Composite Materials

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. UV-VIS Spectroscopy

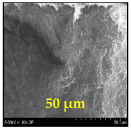

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Particle Size Distribution

3.3. Raman Spectroscopy

3.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Pattern

4. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khaldoun, K.; Khizar, S.; Saidi-Besbes, S.; Zine, N.; Errachid, A.; Elaissari, A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles as an antimicrobial mediator. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025, 11, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Tian, Y.; Qu, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Man, C. Postbiotic-biosynthesized silver nanoparticles anchored on covalent organic frameworks integrated into carboxymethyl chitosan-based film for enhancing antibacterial packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 139143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamman, A.; Jain, P. Synthesis of Chi-sphere silver nanocomposite and nanocomposites of silver, gold, and S@G using a chitosan biopolymer extracted from potato peels and their antimicrobial application. Nano-Structures Nano-Objects 2024, 39, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, N.; Elizalde, V.; Castro, A.; Miraballes, I.; Pardo, H.; Alborés, S. Development and characterization of chitosan–silver nanohybrids with potential application in the control of fungal phytopathogens. MRS Adv. 2023, 9, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Shen, A.; Hu, J. Synthesis of size-tunable chitosan encapsulated gold–silver nanoflowers and their application in SERS imaging of living cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 21261–21267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regiel-Futyra, A.; Kus-Liśkiewicz, M.; Sebastian, V.; Irusta, S.; Arruebo, M.; Kyzioł, A.; Stochel, G. Development of noncytotoxic silver–chitosan nanocomposites for efficient control of biofilm forming microbes. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 52398–52413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirda, E.; Idroes, R.; Khairan, K.; Tallei, T.E.; Ramli, M.; Earlia, N.; Maulana, A.; Idroes, G.M.; Muslem, M.; Jalil, Z. Synthesis of chitosan-silver nanoparticle composite spheres and their antimicrobial activities. Polymers 2021, 13, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Meng, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Chitosan derivatives and their application in biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, D.; Wadaan, M.A.; Mythili, R.; Lee, J. Synthesis of chitosan and gum Arabic functionalized silver nanocomposite for efficient removal of methylene blue and antibacterial activity. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Abdelfattah, A.; Younis, M.A.; Aldalaan, S.M.; Tawfeek, H.M. Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20220546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, D.; Dutta, P.; Dutta, D.; Dutta, A.; Kumar, A.; Mandal, P.; Choudhuri, C.; Mathur, P. Effect of silver nanochitosan on control of seed-borne pathogens and maintaining seed quality of wheat. Phytopathol. Res. 2024, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartmański, M.; Ronowska, A.; Mania, S.; Banach-Kopeć, A.; Kozłowska, J. Biological and antibacterial properties of chitosan-based coatings with AgNPs and CuNPs obtained on oxidized Ti13Zr13Nb titanium alloy. Mater. Lett. 2024, 360, 135997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Sana, S.S.; Jeyavani, J.; Li, H.; Boya, V.K.N.; Vaseeharan, B.; Kim, S.-C.; Zhang, Z. Biomedical applications of chitosan-coated phytogenic silver nanoparticles: An alternative drug to foodborne pathogens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, L.; Le, Q.N.; Tran, K.; Huynh, A.H. Surface Modifications of Silver Nanoparticles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents against Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella enterica. Polymers 2024, 16, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, S.; Adhikari, R.; Khatiwada, P.P.; Devkota, G.; Dahal, K.C. Chitosan-Based Zinc Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles Coating on Postharvest Quality of Papaya. SAARC J. Agric. 2025, 22, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Pricillia, A.; Natarajan, A.; Venkatesan, G. Enhancing sustainability: Chitosan biopolymers with Ag nanoparticles for eco-friendly applications in food packaging. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 25955–25966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, H.N.; Fadhil, M.A.; Hassoun, T.A.Z.; Ahmed, R.T.; Al-Nafiey, A. Green synthesis of novel chitosan-graphene oxide-silver nanoparticle nanocomposite for broad-spectrum antibacterial applications. Oxf. Open Mater. Sci. 2024, 5, itae018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosney, A.; Urbonavičius, M.; Varnagiris, Š.; Ignatjev, I.; Ullah, S.; Barčauskaitė, K. Feasibility study on optimizing chitosan extraction and characterization from shrimp biowaste via acidic demineralization. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 12673–12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, I.Y.; Ahmad, M.S.; Aboellil, A.H.; Mohamed, A.S. Comparative Evaluation of Antibacterial and Toxicity Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles Biosynthesized by Streptomyces, Lemon, and Chitosan. Curr. Nanosci. 2025, 21, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Tan, X.; Fang, M.L.; Zeng, D.; Huang, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Tan, Z. Chitosan-Silver Nanoparticles and Bacillus tequilensis Modulate Antioxidant Pathways and Microbiome Dynamics for Sheath Blight Resistance in Rice. Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pădurețu, C.-C.; Isopescu, R.D.; Gîjiu, C.L.; Rău, I.; Apetroaei, M.R.; Schröder, V. Optimization of chitin extraction procedure from shrimp waste using Taguchi method and chitosan characterization. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2019, 695, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hoqani, H.A.S.; Al-Shaqsi, N.; Hossain, M.A.; Al Sibani, M.A. Isolation and optimization of the method for industrial production of chitin and chitosan from Omani shrimp shell. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 492, 108001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatnah, N.; Azizah, D.; Cahyani, M.D. Synthesis of Chitosan from Crab’s Shell Waste (Portunus pelagicus) in Mertasinga-Cirebon. In International Conference on Progressive Education (ICOPE 2019); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovonramwen, O.; Amoren, E. Extraction of Chitosan from L. squarrosulus (Mushroom) and C. africana (Shrimp) Based and Production of Film Polymer. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2023, 9, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.-T.; Tran, T.N.; Ha, A.C.; Huynh, P.D. Impact of Deacetylation Degree on Properties of Chitosan for Formation of Electrosprayed Nanoparticles. J. Nanotechnol. 2022, 2022, 2288892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitohy, M.; Ewais, A.; Ghany, A.G.A.; Saber, R. Fully deacetylated chitosan from shrimp and crab using minimum heat input. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 66, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosney, A.; Ullah, S.; Barčauskaitė, K. A Review of the Chemical Extraction of Chitosan from Shrimp Wastes and Prediction of Factors Affecting Chitosan Yield by Using an Artificial Neural Network. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Álvarez, M.; Sánchez-Ruíz, F.J.; Domínguez, H.; Vicente-Hinestroza, L.; Illescas, J.; Martínez-Gallegos, S. Molecular dynamics model quantum field for prediction of the interaction between chitosan–silver nanoparticles. Mol. Simul. 2024, 50, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, M.; Fan, J.; Celia, C.; Xie, Y.; Chang, Q.; Deng, X. Synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity of chitosan-chelated silver nanoparticles. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghand, N.; Reiisi, S.; Karimi, B.; Khorasgani, E.M.; Heidari, R. Biosynthesis of Nanocomposite Alginate-Chitosan Loaded with Silver Nanoparticles Coated with Eugenol/Quercetin to Enhance Wound Healing. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 5149–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicea, D.; Nicolae-Maranciuc, A.; Chicea, L.-M. Silver Nanoparticles-Chitosan Nanocomposites: A Comparative Study Regarding Different Chemical Syntheses Procedures and Their Antibacterial Effect. Materials 2024, 17, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, A.; SR, R.R.; Rajan, R.; Ashraf, F. Chitosan silver nanoparticle inspired seaweed (Gracilaria crassa) biodegradable films for seafood packaging. Algal Res. 2024, 78, 103429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kang, D.S.; Anil, S.; Kim, S.-K.; Shim, M.S.; Kim, D.G. Antimicrobial and anticancer activities of porous chitosan-alginate biosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 98, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, E.R.A.; Shenbagarathai, R.; Lavanya, U.; Bhavan, K. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity of Extracted Chitosan-Based Silver Nanoparticles. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2023, 12, e4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.A.; Ahyat, N.; Mohamad, F.; Hamzah, S. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Double-green approach of using chitosan and microwave technique towards antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2020, 10, 5918–5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmehbad, N.Y.; Mohamed, N.A. Designing, preparation and evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of biomaterials based on chitosan modified with silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokatlı, K.; Demirdöven, A. Optimization of chitin and chitosan production from shrimp wastes and characterization. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Lach, R.; Grellmann, W.; Wutzler, A.; Lebek, W.; Godehardt, R.; Yadav, P.N.; Adhikari, R. Synthesis of chitosan from prawn shells and characterization of its structural and antimicrobial properties. Nepal J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derraz, M.; Elouahli, A.; Ennawaoui, C.; Ben Achour, M.A.; Rjafallah, A.; Laadissi, E.M.; Khallok, H.; Hatim, Z.; Hajjaji, A. Extraction and physicochemical characterization of an environmentally friendly biopolymer: Chitosan for composite matrix application. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.P.; Maia, P.; Alencar, N.d.S.; Farias, L.; Andrade, R.F.S.; Souza, D.; Ribaux, D.R.; Franco, L.d.O.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. Recovery of chitin and chitosan from shrimp waste with microwave technique and versatile application. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2019, 86, e0982018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosen, M.F.A. Applications of Chitin and Chitosan; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phat, N.D.T. Recovered Chitin, Chitosan from Shrimp Shell: Structure, Characteristics and Applications. Bachelor’s Thesis, Environmental Chemistry and Technology, Centria University of Applied Sciences, Kokkola, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oe, T.; Dechojarassri, D.; Kakinoki, S.; Kawasaki, H.; Furuike, T.; Tamura, H. Microwave-Assisted Incorporation of AgNP into Chitosan–Alginate Hydrogels for Antimicrobial Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesham, M.; Ayodhya, D.; Madhusudhan, A.; Babu, N.V.; Veerabhadram, G. A novel green one-step synthesis of silver nanoparticles using chitosan: Catalytic activity and antimicrobial studies. Appl. Nanosci. 2014, 4, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, D.; Mandal, P.; Choudhuri, C.; Mathur, P. Impact of silver nanochitosan in protecting wheat seeds from fungal infection and increasing growth parameters. Plant Nano Biol. 2024, 10, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, N.M.; Stapley, A.; Shama, G. Green synthesis of silver and copper nanoparticles using ascorbic acid and chitosan for antimicrobial applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 112, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Ji, H.; Liu, B. A deep learning method for nanoparticle size measurement in SEM images. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 20211–20219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Goshtasby, A. On the Canny edge detector. Pattern Recognit. 2001, 34, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barčauskaitė, K.; Drapanauskaitė, D.; Silva, M.; Murzin, V.; Doyeni, M.; Urbonavicius, M.; Williams, C.F.; Supronienė, S.; Baltrusaitis, J. Low concentrations of Cu2+ in synthetic nutrient containing wastewater inhibit MgCO3-to-struvite transformation. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisa, M.; Ragauskaitė, D.; Shi, J.; Shimizu, S.; Bucko, T.; Williams, C.; Baltrusaitis, J. Interactions of Urea Surfaces with Water as Relative Humidity Obtained from Dynamic Vapor Sorption Experiments, In Situ Single-Particle Raman Spectroscopy, and Ab Initio Calculations. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2023, 7, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, B.H.; Ba, D.T.; Pham, D.G.; Van Khai, T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Tran, L.D. Microwave-assisted synthesis of silver nanoparticles using chitosan: A novel approach. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2014, 29, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Lee, G.; Li, P.; Baik, H.; Yi, G.-R.; Park, J.H. Expandable crosslinked polymer coatings on silicon nanoparticle anode toward high-rate and long-cycle-life lithium-ion battery. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 571, 151294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Yngard, R.A.; Lin, Y. Silver nanoparticles: Green synthesis and their antimicrobial activities. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 145, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Mayanovic, R.A. A Review of the Preparation, Characterization, and Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles in Nanomedicine. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nate, Z.; Moloto, M.J.; Mubiayi, P.K.; Sibiya, P.N. Green synthesis of chitosan capped silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activity. MRS Adv. 2018, 3, 2505–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, A.; Alimohammadian, M.H.; Gazori, T.; Riazi-Rad, F.; Fatemi, S.M.R.; Parizadeh, A.; Haririan, I.; Havaskary, M. Comparison of chitosan, alginate and chitosan/alginate nanoparticles with respect to their size, stability, toxicity and transfection. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2014, 4, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescola, A.; Canale, C.; Fragouli, D.; Athanassiou, A. Controlled formation of gold nanostructures on biopolymer films upon electromagnetic radiation. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 415601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Moisture Content (%) | Ash Content (%) | Degree of Deacetylation (DD%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AS3 | 0.34 | 3.5 | 99.35 |

| LH1 | 0.56 | 2.6 | 99.40 |

| HC1 | 1.32 | 0.90 | 91.1 |

| HC2 | 1.35 | 0.76 | 91.3 |

| DP4 | 0.19 | 0.92 | 99.24 |

| L10 | 2 | 1.06 | 99.42 |

| L20 | 2.74 | 0.70 | 99.38 |

| Sample ID | SEM.M1 | Particle SegmentationM1 | SEM.M2 | Particle SegmentationM2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS3 |  |  |  |  |

| DP4 |  |  |  |  |

| HC1 |  |  |  |  |

| HC2 |  |  |  |  |

| L10 |  |  |  |  |

| L20 |  |  |  |  |

| LH1 |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosney, A.; Kundrotaitė, A.; Drapanauskaitė, D.; Urbonavičius, M.; Varnagiris, Š.; Ullah, S.; Barčauskaitė, K. Green Synthesis of Chitosan Silver Nanoparticle Composite Materials: A Comparative Study of Microwave and One-Pot Reduction Methods. Polymers 2025, 17, 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212960

Hosney A, Kundrotaitė A, Drapanauskaitė D, Urbonavičius M, Varnagiris Š, Ullah S, Barčauskaitė K. Green Synthesis of Chitosan Silver Nanoparticle Composite Materials: A Comparative Study of Microwave and One-Pot Reduction Methods. Polymers. 2025; 17(21):2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212960

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosney, Ahmed, Algimanta Kundrotaitė, Donata Drapanauskaitė, Marius Urbonavičius, Šarūnas Varnagiris, Sana Ullah, and Karolina Barčauskaitė. 2025. "Green Synthesis of Chitosan Silver Nanoparticle Composite Materials: A Comparative Study of Microwave and One-Pot Reduction Methods" Polymers 17, no. 21: 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212960

APA StyleHosney, A., Kundrotaitė, A., Drapanauskaitė, D., Urbonavičius, M., Varnagiris, Š., Ullah, S., & Barčauskaitė, K. (2025). Green Synthesis of Chitosan Silver Nanoparticle Composite Materials: A Comparative Study of Microwave and One-Pot Reduction Methods. Polymers, 17(21), 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212960