Optimization of Metal Injection Molding Processing Conditions for Reducing Black Lines and Meld Lines in Bone Plates

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Bone Plates

1.2. Metal Injection Molding

1.3. Optimization Method to Improve MIM Process

2. Theory Analysis, Black Lines and Meld Lines

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Constitutive Equation and Viscosity Mode

2.3. Particle-Phase Conservation Equation

2.4. Shear-Induced Phase Separation Effect

2.5. Formation of Black Lines

2.6. Formation of Meld Lines

2.7. Analysis of Metal Powder Concentration and Temperature Distributions

3. MIM Simulations and Optimization Methods

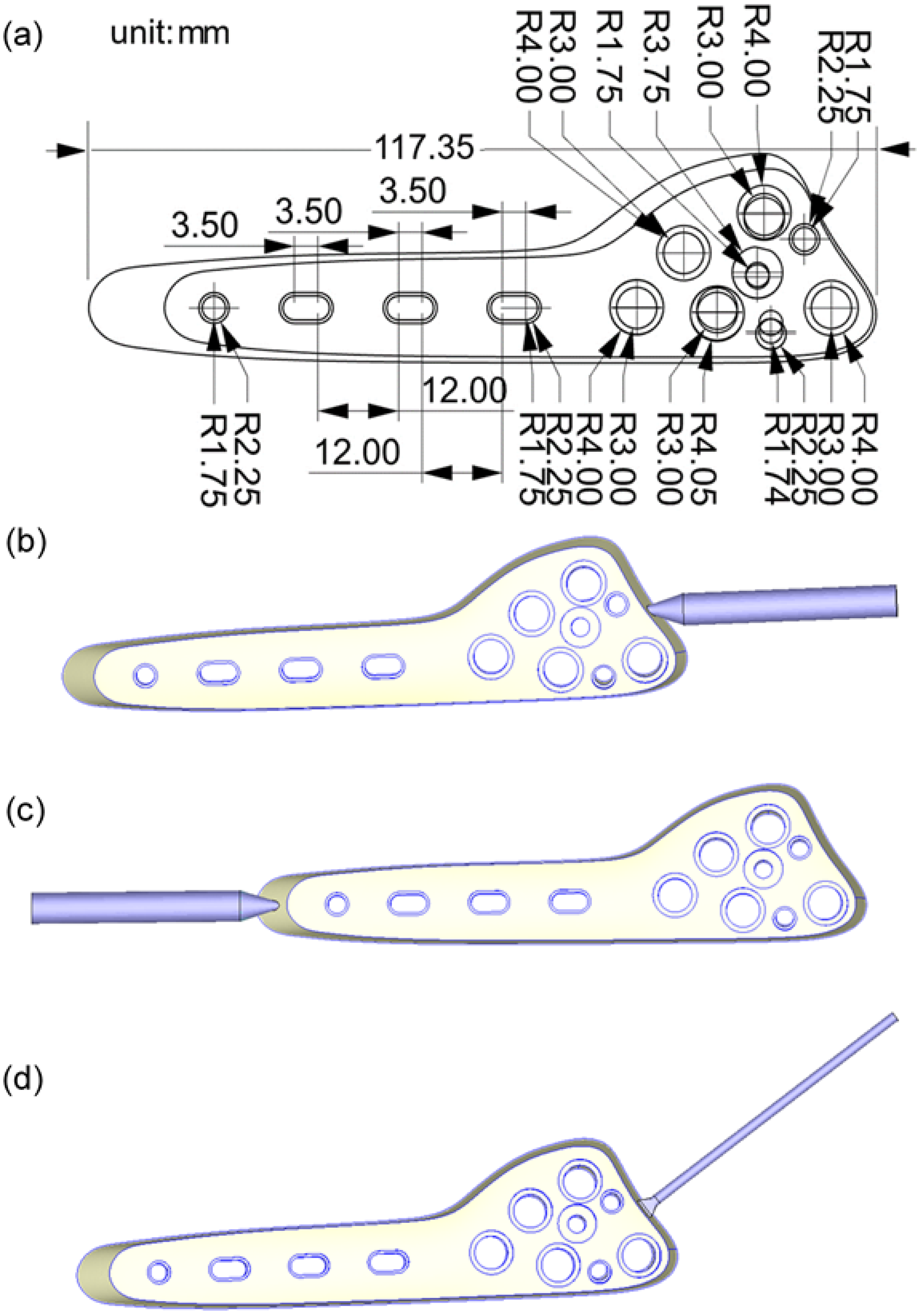

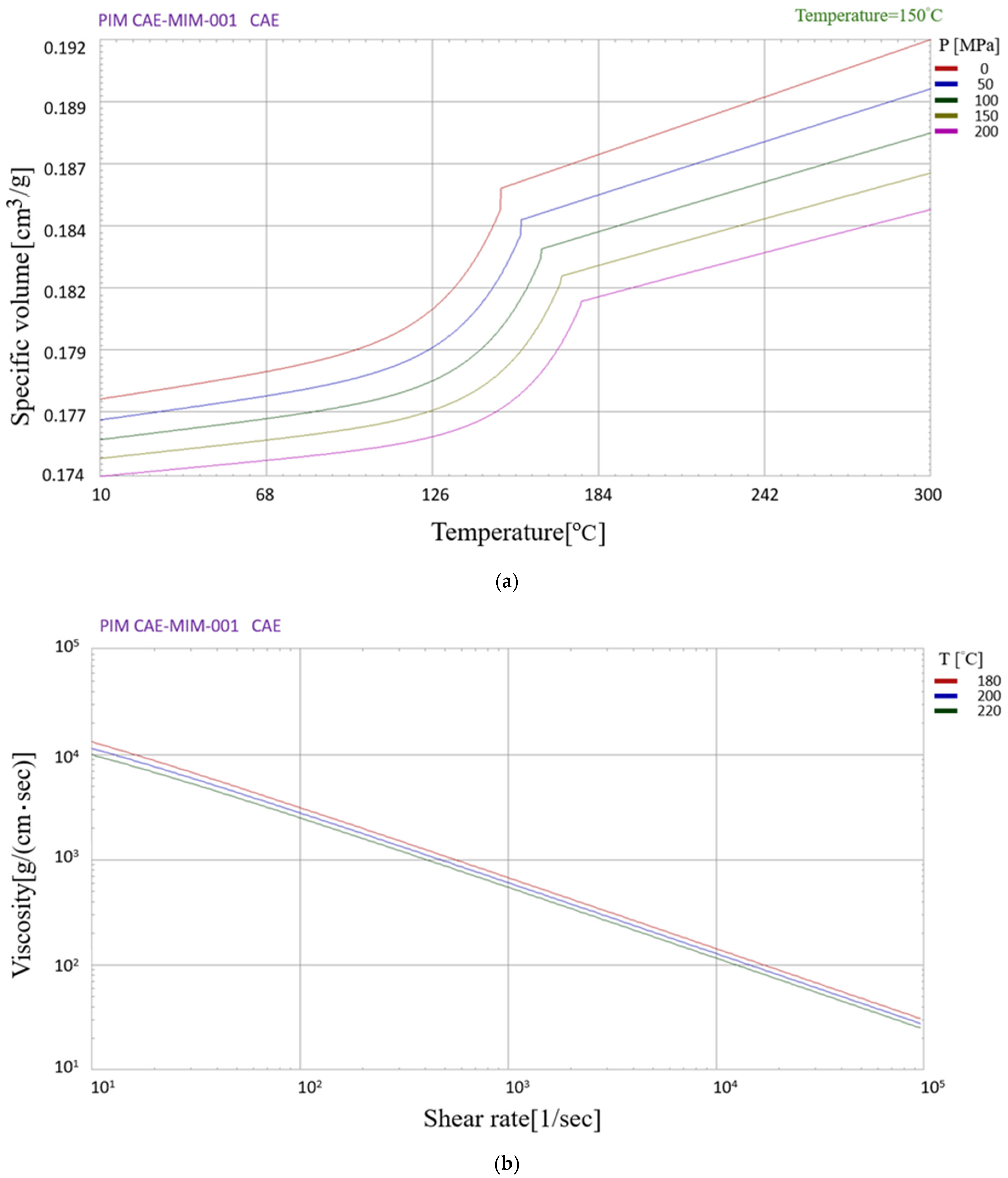

3.1. Geometry, Material, and Mold Flow Analysis

3.2. Taguchi Experiments

3.3. Grey Relational Analysis (GRA)

3.4. Robust Multi-Criteria Optimization (RMCO)

4. Results and Discussion

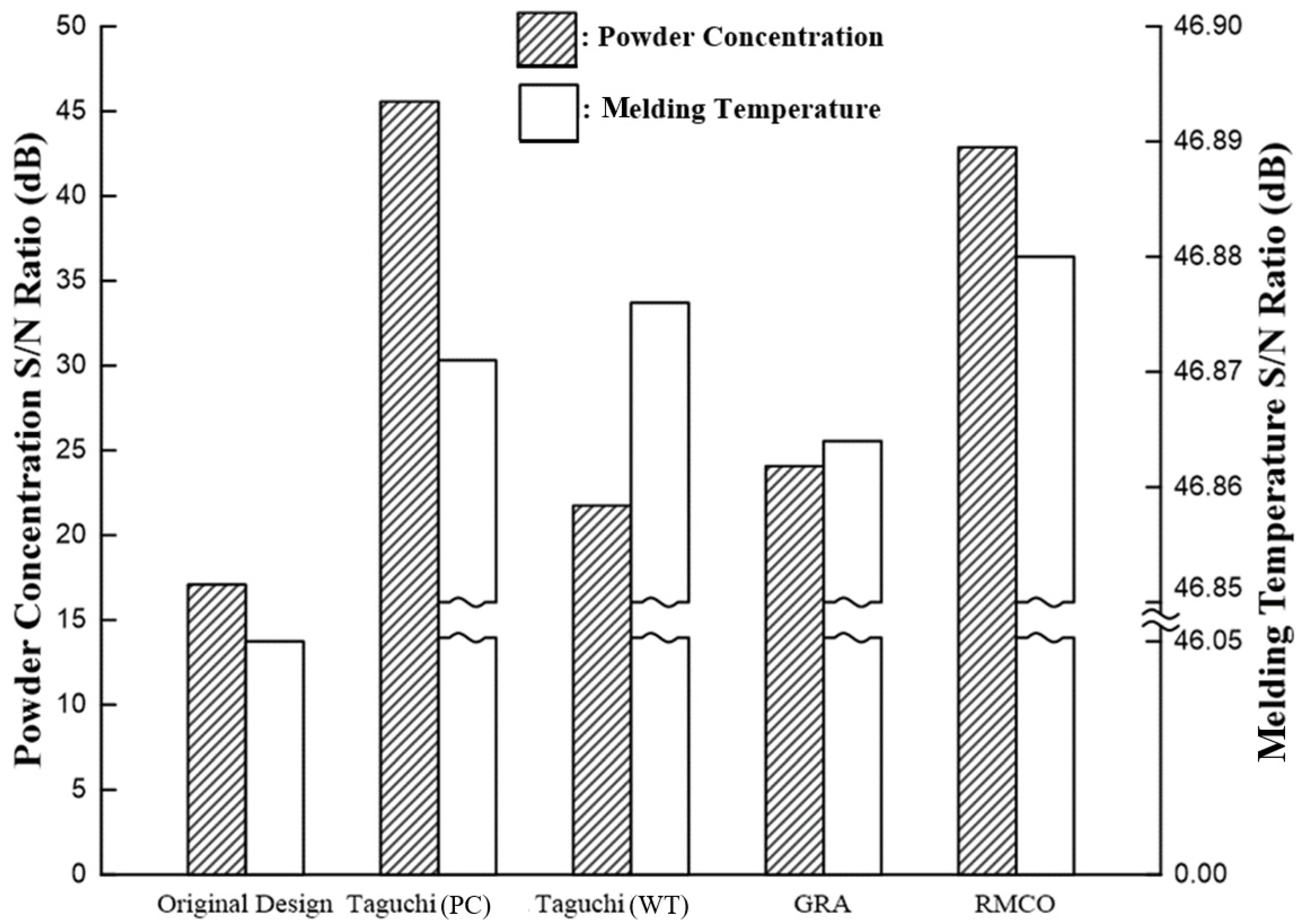

4.1. Single-Objective Optimization with Taguchi Method

4.2. Two-Objective Optimization with GRA

4.3. Optimization Analysis Results from RMCO

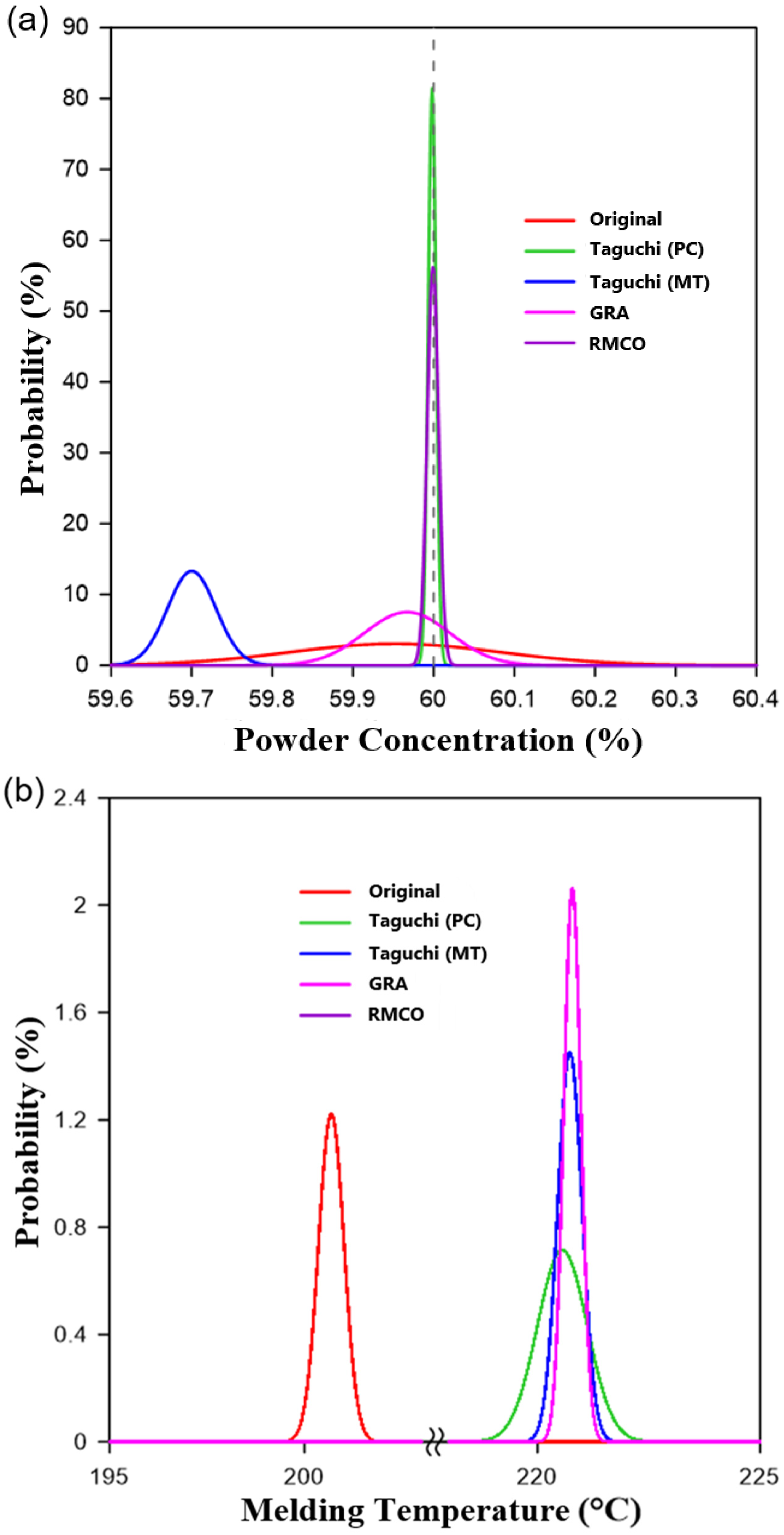

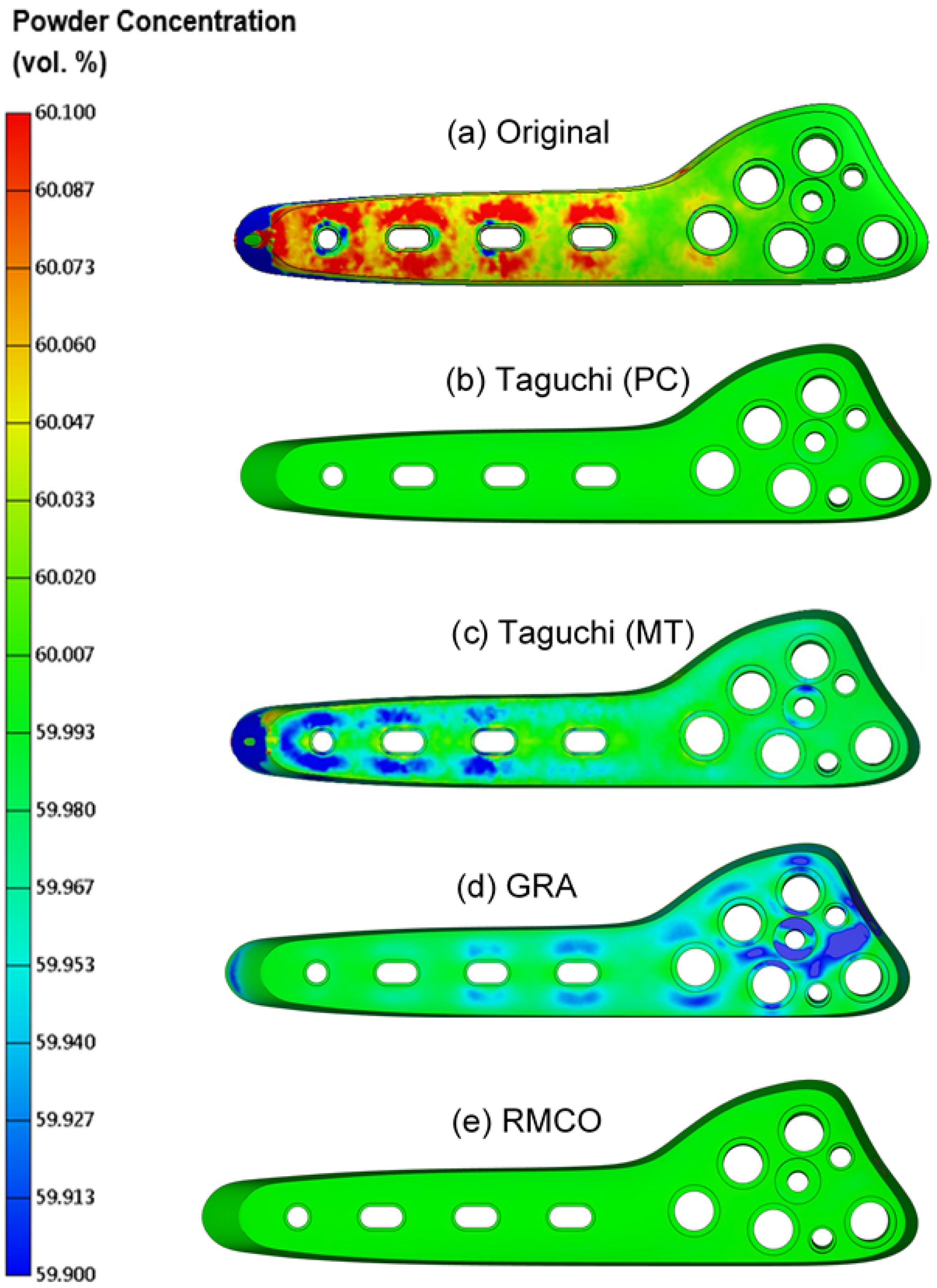

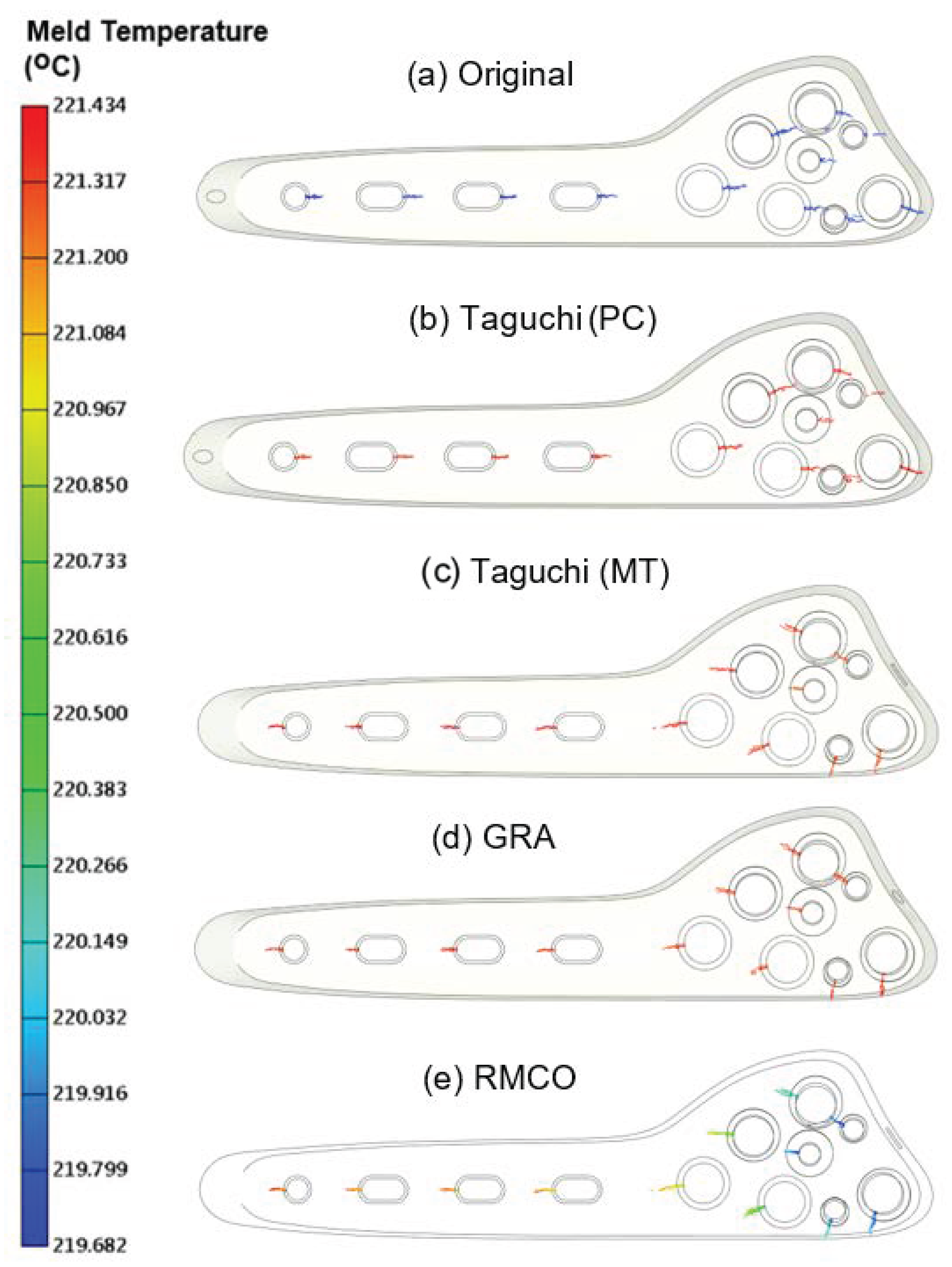

4.4. Improvement Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Pater, T.J.; Grindel, S.I.; Schmeling, G.J.; Wang, M. Stability of unicortical locked fixation versus bicortical non-locked fixation for forearm fractures. Bone Res. 2014, 2, 14014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourisa, J.; Rouhi, G. Biomechanical evaluation of intramedullary nail and bone plate for the fixation of distal metaphyseal fractures. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 56, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, R.D.; Kubiak, E.; Horwitz, D.S. Techniques for the surgical treatment of distal tibia fractures. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 45, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, I.H.; Gani, N.U.; Yaseen, M.; Bashir, A.; Bhat, M.S.; Farooq, M. Operative Management of Distal Tibial Extra-articular Fractures—Intramedullary Nail Versus Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Plate Osteosynthesis. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2017, 19, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Qin, L.; Yangd, K.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, D. Materials evolution of bone plates for internal fixation of bone fractures: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 36, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R.M.; Bose, A. Injection Moulding of Metals and Ceramics; Metal Powder Industries Federation: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997; p. 413. [Google Scholar]

- Berginc, B.; Kampus, Z.; Sustarsic, B. The Use of Taguchi Approach to Determine the Influence of Injection Molding Parameters on the Properties of Green Parts. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2006, 15, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.M.; Wu, J.J.; Tan, C.M. Processing Optimization for Metal Injection Molding of Orthodontic Braces Considering Powder Concentration Distribution of Feedstock. Polymers 2020, 12, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Hung, Y.Y.; Tan, C.M. Hybrid Taguchi–Gray Relation Analysis Method for Design of Metal Powder Injection-Molded Artificial Knee Joints with Optimal Powder Concentration and Volume Shrinkage. Polymers 2021, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornagel, M. MIM-Simulation: A Virtual Study on Phase Separation. In Proceedings of the EURO PM 2009, Copenhagen, Denmark, 12–14 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.; Heaney, D.F.; Myers, N.S. Metal Injection Molding (MIM) of heavy alloys, refractory metals, and hardmetals. In Handbook of Metal Injection Molding; A volume in Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 526–567. [Google Scholar]

- German, R.M. Metal Powder Injection Molding (MIM): Key trends and markets. In Handbook of Metal Injection Molding; A volume in Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Thornagel, M. Injection moulding simulation: New developments offer rewards for the PIM industry. Powder Inject. Mould. Int. 2012, 6, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- German, R.M. Homogeneity Effects on Feedstock Viscosity in Powder Injection Moulding. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1994, 77, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriere, T.; Liu, B.; Gelin, J.C. Determination of the Optimal Parameters in the Metal Injection Moulding from Experiments and Numerical Modeling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003, 143–144, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.Y.M.; Muhamad, N.; Jamaludin, K.R. Optimization of injection molding parameters for WC Co feedstocks. J. Teknol. Sci. Eng. 2013, 63, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, P.J. Taguchi Techniques for Quality Engineering; Tata McGraw Hill: Delhi, India, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.K. Design of Experiments Using the Taguchi Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 538. [Google Scholar]

- Tadmor, Z.; Gogos, C.G. Principles of Polymer Processing; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liepsch, D. An introduction to biofluid mechanics-basic models and applications. J. Biomech. 2002, 35, 415–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.M.; Morris, J.F. Normal Stress-Driven Migration and Axial Development in Pressure-Driven Flow of Concentrated Suspensions. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2006, 135, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.F.; Zaki, W.N. Sedimentation and fluidization: Part I. Trans. Inst. Chem. Eng. 1954, 32, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.F.; Boulay, F. Curvilinear flows of noncolloidal suspensions: The role of normal stresses. J. Rheol. 1999, 43, 1213–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.J.; Armstrong, R.C.; Brown, R.A.; Graham, A.; Abbott, J.R. A constitutive model for concentrated suspensions that accounts for shear induced particle migration. Phys. Fluids A 1992, 4, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFC/2024/ENU/?guid=LM_WELD_AND_MELD_LINES (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Guo, S.; Ait-Kadi, A. A study on weld line morphology and mechanical strength of injection molded polystyrene/poly (methyl methacrylate) blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 84, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, K.; Sedlacek, F. Effect of Melt Temperature on Weld Line Strength. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 801, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merah, N.; Irfan-ul-Haqb, M.; Khana, Z. Temperature and Weld-Line Effects on Mechanical Properties of CPVC. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003, 142, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, D. Modelling and prediction of weld line location and properties based on injection moulding simulation. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2004, 21, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.acumed.net/products/shoulder/polarus-proximal-humeral-plating-system/ (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Available online: https://support.moldex3d.com/2024/en/7-8_powderinjectionmolding(pim).html (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Lee, H.H. Taguchi Methods Principles and Practices of Quality Design; GauLih Book Co. Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, J.L.; Robin, A.; Silva, M.B.; Baldan, C.A.; Peres, M.P. Electrodeposition of copper on titanium wires: Taguchi experimental design approach. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J. Control problems of grey systems. Syst. Control Lett. 1982, 5, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Hsia, K.H.; Wu, J.H. A study on the data preprocessing in grey relation analysis. J. Chin. Grey Syst. 1998, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Arun, K.; Sundar, K. A robust multi-criteria optimization approach. Pergamon Theory 1997, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.Z.; Chalup, S.; Mirjalili, S.; Noman, N. Robust Multi-Objective optimization using Conditional Pareto Optimal Dominance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedali, M.; Andrew, L.; Jin, S.D. Confidence-based robust optimisation using multi-objective meta-heuristics. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2018, 43, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Gupta, H. Introducing Robustness in Multi-Objective Optimization. Evol. Comput. 2006, 14, 463–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrel, V.; Murat, C.; Thiele, A. Recent advances in robust optimization: An overview. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 235, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type I | Type II | Type III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part element | 377,600 | 376,278 | 372,889 |

| Node number | 401,795 | 407,103 | 448,419 |

| Measure node | 14,646 | 14,646 | 14,646 |

| Property | PP with 60% vol. Stainless Steel Powder | PP |

|---|---|---|

| ρ: density [g/cm3] | 5.1 | 0.91 |

| μ: viscosity [Pa-s] | (3.5~5.5) × 102 (T: 190–230 °C; 10–105) | (6.8~9) × 102 (T: 190–270 °C; 10–105) |

| k: heat conduction [erg/(s·cm·K)] | 8.5 × 10−5 | 1.5 × 10−4 |

| α: thermal expansion [1/K] | 8 × 104 | 2.52 × 104 |

| Cp: specific heat [erg/(g·K)] | 8 × 106 | 3.1 × 107 |

| Cv: specific volume [cm3/g] | 0.183–0.201 (T: 10–300 °C; P: 0–200 MPa) | 0.777–0.974 (T: 10–300 °C; P: 0–200 MPa) |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Type | Melt Temp. | Mold Temp. | Injection Velocity | Packing Time | Packing Pressure | |

| (℃) | (℃) | (mm/s) | (s) | (250 MPa) | ||

| Level 1 | Type I | 180 | 60 | 65 | 4.3 | 20% |

| Level 2 | Type II | 190 | 70 | 75 | 4.8 | 40% |

| Level 3 | Type III | 200 | 80 | 85 | 5.3 | 60% |

| Level 4 | Type I | 210 | 90 | 95 | 5.8 | 80% |

| Level 5 | Type II | 220 | 100 | 105 | 6.3 | 100% |

| Trials | A | B (°C) | C (°C) | D (mm/s) | E (s) | F (%) | S/N1 Powder Concentration | S/N2 Melding Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type I | 180 | 60 | 65 | 4.3 | 20 | 12.82 | 42.78 |

| 2 | Type I | 190 | 70 | 75 | 4.8 | 40 | 18.98 | 45.60 |

| 3 | Type I | 200 | 80 | 85 | 5.3 | 60 | 28.90 | 46.04 |

| 4 | Type I | 210 | 90 | 95 | 5.8 | 80 | 27.88 | 46.46 |

| 5 | Type I | 220 | 100 | 105 | 6.3 | 100 | 32.49 | 46.74 |

| 6 | Type II | 180 | 70 | 85 | 5.8 | 100 | 12.09 | 45.16 |

| 7 | Type II | 190 | 80 | 95 | 6.3 | 20 | 15.70 | 45.62 |

| 8 | Type II | 200 | 90 | 105 | 4.3 | 40 | 19.33 | 46.07 |

| 9 | Type II | 210 | 100 | 65 | 4.8 | 60 | 18.46 | 46.46 |

| 10 | Type II | 220 | 60 | 75 | 5.3 | 80 | 21.74 | 46.87 |

| 11 | Type III | 180 | 80 | 105 | 4.8 | 80 | 32.96 | 45.15 |

| 12 | Type III | 190 | 90 | 65 | 5.3 | 100 | 27.64 | 45.56 |

| 13 | Type III | 200 | 100 | 75 | 5.3 | 20 | 39.47 | 46.05 |

| 14 | Type III | 210 | 60 | 85 | 6.3 | 40 | 47.61 | 46.47 |

| 15 | Type III | 220 | 70 | 95 | 4.3 | 60 | 42.94 | 46.87 |

| 16 | Type I | 180 | 90 | 75 | 6.3 | 60 | 14.28 | 45.13 |

| 17 | Type I | 190 | 100 | 85 | 4.3 | 80 | 17.96 | 45.68 |

| 18 | Type I | 200 | 60 | 95 | 4.8 | 100 | 28.69 | 46.05 |

| 19 | Type I | 210 | 70 | 105 | 5.3 | 20 | 28.21 | 46.55 |

| 20 | Type I | 220 | 80 | 65 | 5.8 | 40 | 34.18 | 46.51 |

| 21 | Type II | 180 | 100 | 95 | 5.3 | 40 | 13.14 | 45.80 |

| 22 | Type II | 190 | 60 | 105 | 5.8 | 60 | 16.48 | 45.63 |

| 23 | Type II | 200 | 70 | 65 | 6.3 | 80 | 15.03 | 46.05 |

| 24 | Type II | 210 | 80 | 75 | 4.3 | 100 | 21.80 | 46.87 |

| 25 | Type II | 220 | 90 | 85 | 4.8 | 20 | 22.30 | 46.87 |

| Origin | - | - | - | - | - | - | 46.05 |

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 | Range | Rank | SS | DOF | %Cont. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 24.440 | 17.607 | 38.122 | 1 | 1818.63 | 4 | 66.7% | |||

| B | 17.057 | 19.350 | 26.286 | 28.794 | 30.729 | 13.672 | 2 | 711.66 | 4 | 26.1% |

| C | 25.468 | 23.450 | 26.708 | 22.286 | 24.304 | 4.4219 | 3 | 59.199 | 4 | 2.2% |

| D | 21.627 | 23.251 | 25.772 | 25.671 | 25.895 | 4.2684 | 4 | 73.674 | 4 | 2.7% |

| E | 22.969 | 24.277 | 23.926 | 26.019 | 25.023 | 3.0502 | 6 | 26.445 | 4 | 1.0% |

| F | 23.702 | 26.648 | 24.211 | 23.112 | 24.542 | 3.5359 | 5 | 36.234 | 4 | 1.3% |

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 | Range | Rank | SS | DOF | %Cont. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 45.755 | 46.139 | 46.020 | 0.384 | 6 | 0.644 | 4 | 3.7% | ||

| B | 44.804 | 45.618 | 46.050 | 46.564 | 46.772 | 1.968 | 1 | 12.430 | 4 | 71.7% |

| C | 45.558 | 46.045 | 46.038 | 46.019 | 46.148 | 0.590 | 3 | 1.068 | 4 | 6.2% |

| D | 45.472 | 46.104 | 46.045 | 46.160 | 46.027 | 0.688 | 2 | 1.551 | 4 | 8.9% |

| E | 45.653 | 46.026 | 46.165 | 45.961 | 46.003 | 0.512 | 5 | 0.712 | 4 | 4.1% |

| F | 45.577 | 46.090 | 46.026 | 46.041 | 46.074 | 0.513 | 4 | 0.939 | 4 | 5.4% |

| Trials | Powder Concentration | MeldingTemperature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/N | Xi(k) | △i(k) | γ(k) | S/N | Xi(k) | △i(k) | γ(k) | |

| 1 | 12.82 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.33798 | 42.78 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.33333 |

| 2 | 18.98 | 0.19 | 0.81 | 0.38281 | 45.60 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.61603 |

| 3 | 28.90 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.48700 | 46.04 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.71088 |

| 4 | 27.88 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.47375 | 46.46 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.83314 |

| 5 | 32.49 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.54018 | 46.74 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.93944 |

| 6 | 12.09 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.33333 | 45.16 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.54353 |

| 7 | 15.70 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.35758 | 45.62 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.62045 |

| 8 | 19.33 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.38578 | 46.07 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.71695 |

| 9 | 18.46 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.37861 | 46.46 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.83290 |

| 10 | 21.74 | 0.27 | 0.73 | 0.40702 | 46.87 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.99657 |

| 11 | 32.96 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.54789 | 45.15 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.54237 |

| 12 | 27.64 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.47067 | 45.56 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.60905 |

| 13 | 39.47 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 0.68561 | 46.05 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.71345 |

| 14 | 47.61 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00000 | 46.47 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.83564 |

| 15 | 42.94 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.79158 | 46.87 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.99728 |

| 16 | 14.28 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.34761 | 45.13 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.54033 |

| 17 | 17.96 | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.37457 | 45.68 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.63171 |

| 18 | 28.69 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.48421 | 46.05 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.71178 |

| 19 | 28.21 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.47798 | 46.55 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 0.86478 |

| 20 | 34.18 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.56938 | 46.51 | 0.91 | 0.09 | 0.84898 |

| 21 | 13.14 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.34004 | 45.80 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.65642 |

| 22 | 16.48 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.36326 | 45.63 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.62112 |

| 23 | 15.03 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.35282 | 46.05 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.71219 |

| 24 | 21.80 | 0.27 | 0.73 | 0.40762 | 46.87 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.99766 |

| 25 | 22.30 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.41236 | 46.87 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00000 |

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 | Range | Rank | SS | DOF | %Cont. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.575 | 0.572 | 0.719 | 0.148 | 1 | 0.118 | 4 | 26.4% | ||

| B | 0.452 | 0.505 | 0.596 | 0.710 | 0.750 | 0.144 | 2 | 0.328 | 4 | 73.3% |

| C | 0.609 | 0.607 | 0.609 | 0.579 | 0.609 | 0.002 | 6 | 0.004 | 4 | 0.8% |

| D | 0.545 | 0.609 | 0.633 | 0.627 | 0.600 | 0.088 | 3 | 0.025 | 4 | 5.5% |

| E | 0.597 | 0.591 | 0.602 | 0.599 | 0.625 | 0.011 | 5 | 0.003 | 4 | 0.7% |

| F | 0.580 | 0.635 | 0.607 | 0.587 | 0.604 | 0.055 | 4 | 0.009 | 4 | 2.0% |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Type | Melt Temp. | Mold Temp. | Injection Velocity | Packing Time | Packing Pressure | |

| (℃) | (℃) | (mm/sec) | (s) | (250 MPa) | ||

| Level 1 | Type I | 220 | 60 | 65 | 4.3 | 20% |

| Level 2 | Type II | 220 | 70 | 75 | 4.8 | 40% |

| Level 3 | Type III | 220 | 80 | 85 | 5.3 | 60% |

| Level 4 | Type I | 220 | 90 | 95 | 5.8 | 80% |

| Level 5 | Type II | 220 | 100 | 105 | 6.3 | 100% |

| Trials | A (-) | B (°C) | C (°C) | D (mm/s) | E (s) | F (%) | S/N1 Power Concentration | S/N2 Melding Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type I | 220 | 60 | 65 | 4.3 | 20 | 29.20548 | 46.85253 |

| 2 | Type I | 220 | 70 | 75 | 4.8 | 40 | 25.44311 | 46.46912 |

| 3 | Type I | 220 | 80 | 85 | 5.3 | 60 | 23.81951 | 46.86169 |

| 4 | Type I | 220 | 90 | 95 | 5.8 | 80 | 31.46265 | 46.8638 |

| 5 | Type I | 220 | 10 | 105 | 6.3 | 100 | 30.67761 | 46.86618 |

| 6 | Type II | 220 | 70 | 85 | 5.8 | 100 | 23.101 | 46.87297 |

| 7 | Type II | 220 | 80 | 95 | 6.3 | 20 | 21.63819 | 46.87698 |

| 8 | Type II | 220 | 90 | 105 | 4.3 | 40 | 21.83297 | 46.88015 |

| 9 | Type II | 220 | 100 | 65 | 4.8 | 60 | 20.49977 | 46.86064 |

| 10 | Type II | 220 | 60 | 75 | 5.3 | 80 | 22.70512 | 46.86709 |

| 11 | Type III | 220 | 80 | 105 | 4.8 | 80 | 42.86495 | 46.87078 |

| 12 | Type III | 220 | 90 | 65 | 5.3 | 100 | 37.05373 | 46.86319 |

| 13 | Type III | 220 | 100 | 75 | 5.3 | 20 | 41.05609 | 46.8677 |

| 14 | Type III | 220 | 60 | 85 | 6.3 | 40 | 42.85524 | 46.86651 |

| 15 | Type III | 220 | 70 | 95 | 4.3 | 60 | 42.57005 | 46.86868 |

| 16 | Type I | 220 | 90 | 75 | 6.3 | 60 | 31.62564 | 46.85823 |

| 17 | Type I | 220 | 100 | 85 | 4.3 | 80 | 30.41522 | 46.86142 |

| 18 | Type I | 220 | 60 | 95 | 4.8 | 100 | 29.11894 | 46.86429 |

| 19 | Type I | 220 | 70 | 105 | 5.3 | 20 | 26.63406 | 46.86636 |

| 20 | Type I | 220 | 80 | 65 | 5.8 | 40 | 26.47247 | 46.85045 |

| 21 | Type II | 220 | 100 | 95 | 5.3 | 40 | 21.92641 | 46.8772 |

| 22 | Type II | 220 | 60 | 105 | 5.8 | 60 | 21.5193 | 46.87977 |

| 23 | Type II | 220 | 70 | 65 | 6.3 | 80 | 19.86008 | 46.86071 |

| 24 | Type II | 220 | 80 | 75 | 4.3 | 100 | 22.83108 | 46.86736 |

| 25 | Type II | 220 | 90 | 85 | 4.8 | 20 | 22.4223 | 46.87324 |

| MAX | 42.86495 | 46.88015 |

| Taguchi Trials | S/N Ratios(dB) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Design | Taguchi Method (Powder Concentration) | Taguchi Method (Meld Temperature) | GRA | RMCO | |

| Powder Concentration | 17.080 | 45.557 | 21.738 | 24.067 | 42.865 |

| (μ(%), σ) | (59.952, 0.1313) | (59.998, 0.0049) | (59.700, 0.0300) | (59.967, 0.0531) | (59.999, 0.0071) |

| Melding Temperature | 46.049 | 46.871 | 46.876 | 46.864 | 46.880 |

| (μ(°C), σ) | (200.69, 0.3266) | (220.559, 0.5587) | (220.728, 0.2750) | (220.784, 0.1935) | (220.56, 0.5587) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-M.; Yen, P.-Y.; Tan, C.-M. Optimization of Metal Injection Molding Processing Conditions for Reducing Black Lines and Meld Lines in Bone Plates. Polymers 2024, 16, 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16233241

Lin C-M, Yen P-Y, Tan C-M. Optimization of Metal Injection Molding Processing Conditions for Reducing Black Lines and Meld Lines in Bone Plates. Polymers. 2024; 16(23):3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16233241

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Chao-Ming, Po-Yu Yen, and Chung-Ming Tan. 2024. "Optimization of Metal Injection Molding Processing Conditions for Reducing Black Lines and Meld Lines in Bone Plates" Polymers 16, no. 23: 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16233241

APA StyleLin, C.-M., Yen, P.-Y., & Tan, C.-M. (2024). Optimization of Metal Injection Molding Processing Conditions for Reducing Black Lines and Meld Lines in Bone Plates. Polymers, 16(23), 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16233241