Agro-Industrial Plant Proteins in Electrospun Materials for Biomedical Application

Abstract

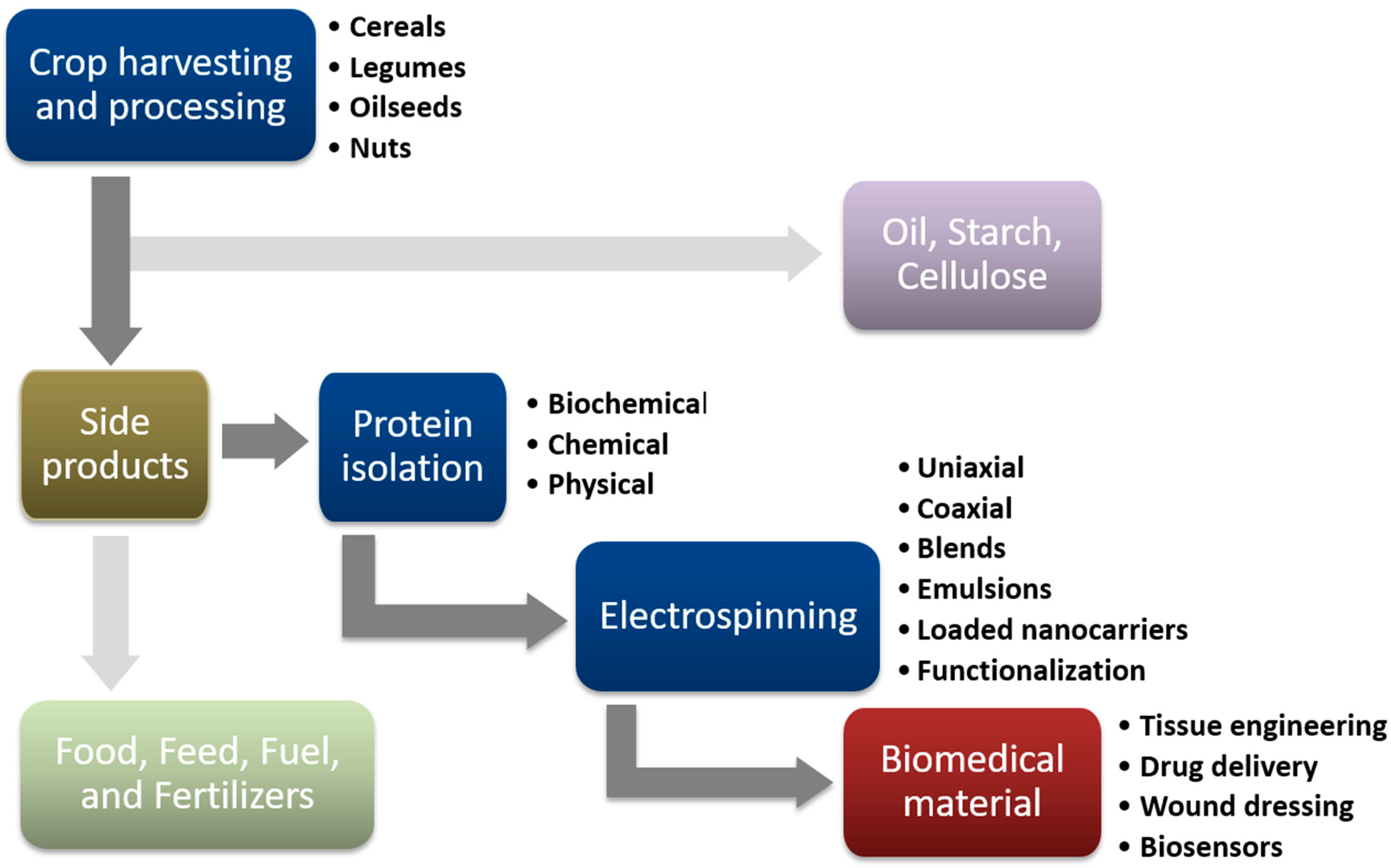

1. Introduction

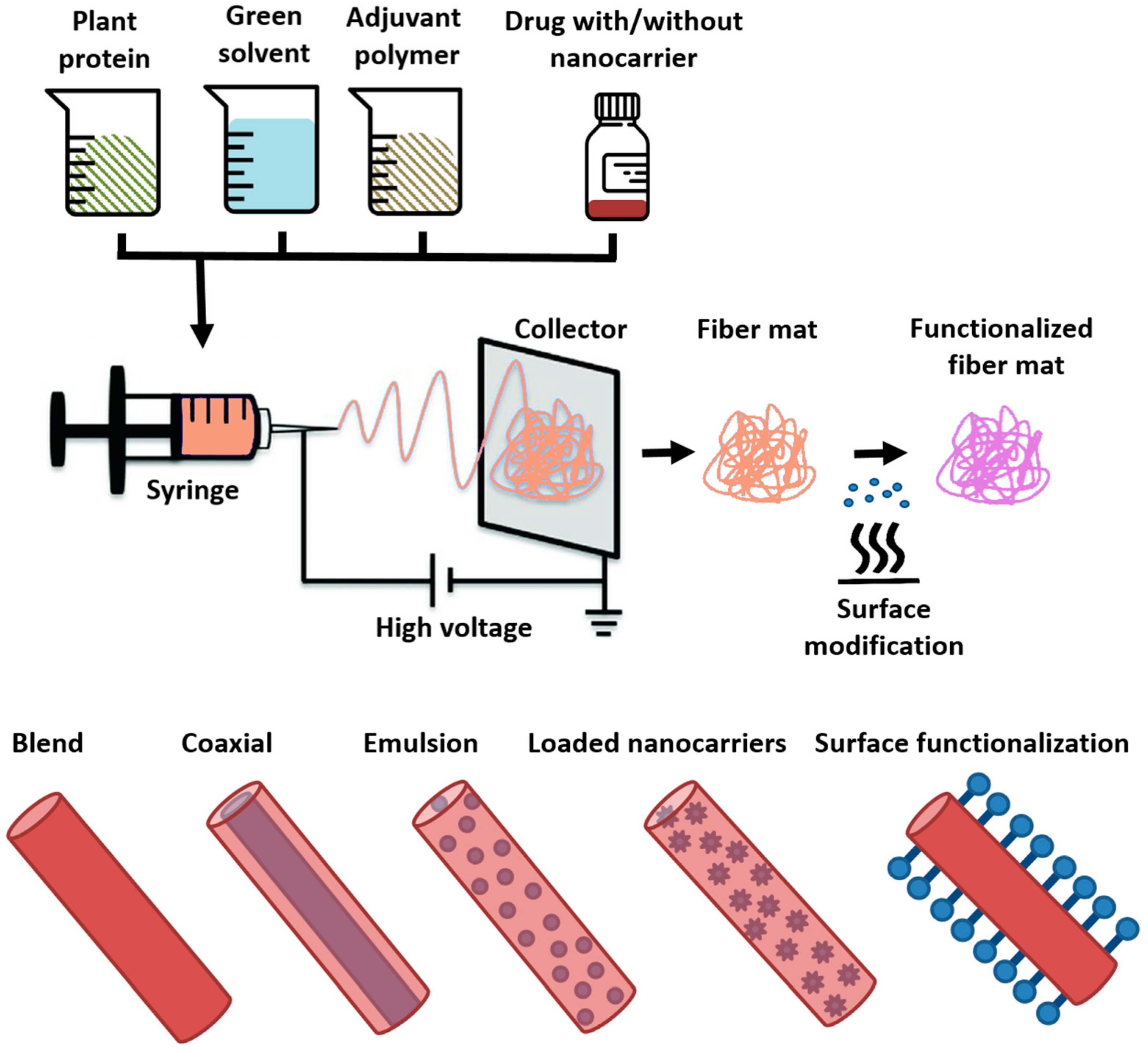

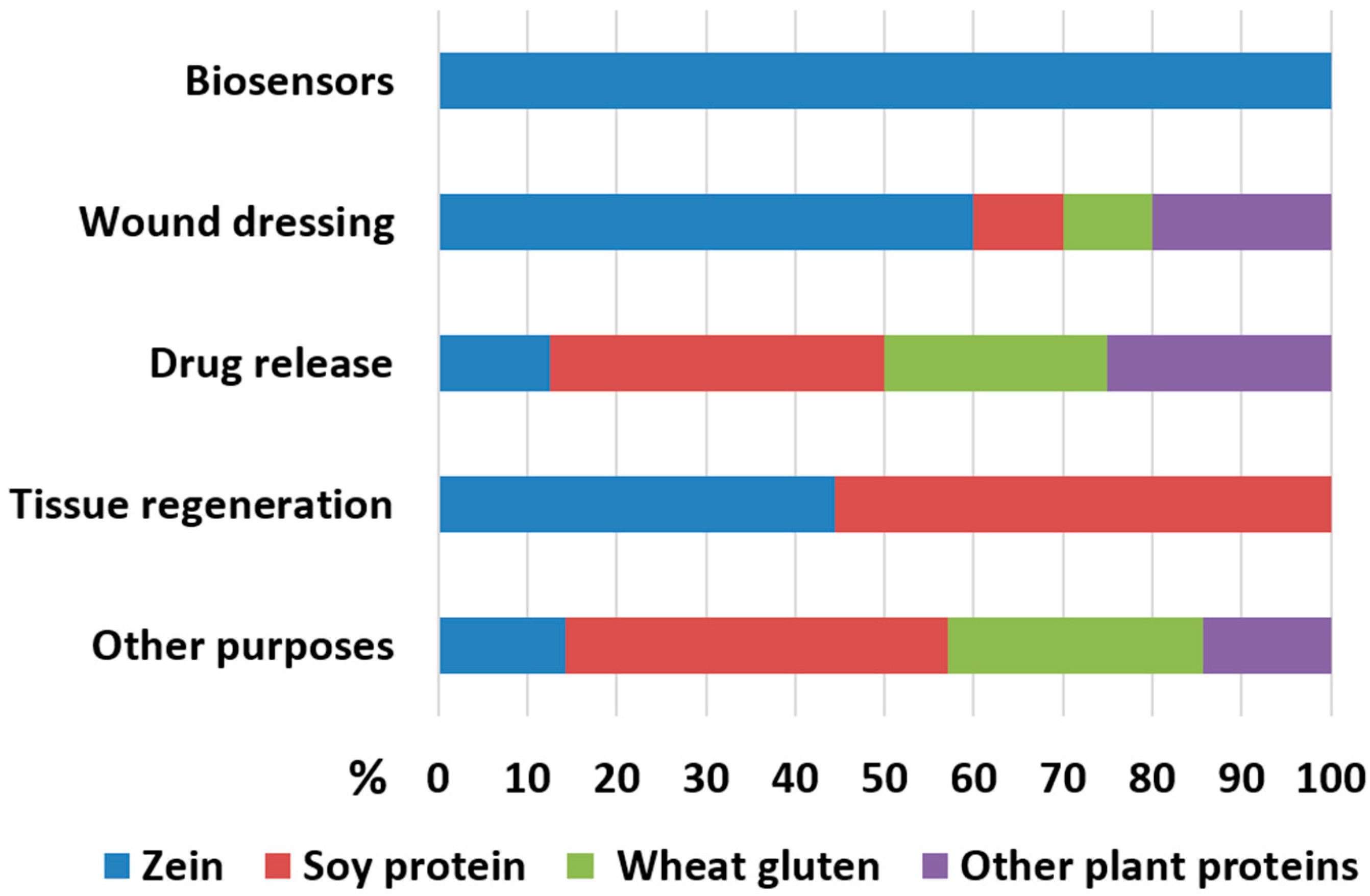

2. Electrospinning of Plant Protein Fibers—Modes and Purposes

3. Recent Trends in Biomedical Application of Electrospun Plant Proteins

3.1. Zein—Source and Properties

Biomedical Application of Electrospun Zein

| Protein | Adjuvant Polymer/Solvent | Electrospinning Type | Drug, Bioactive Compound and/or Condition Tested | Biomedical Effects and Suggested Application of the Electrospun Material | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zein | None/Acetic acid | Uniaxial | Curcumin carbon dots | Biosensors for bacterial contamination | [40] |

| None/Ethanol | Uniaxial | Alizarin | Biosensors for bacterial contamination | [41] | |

| SF, Chitosan (Ch)/Formic acid | Uniaxial | Curcumin; Zein with and w/o adjuvant polymers | Better fibroblast growth in blends with SF and Ch; Sustained drug release; Wound dressing | [44] | |

| * C: PEO (no Zein)/Ethanol ** S: None,/Ethanol | Coaxial | Resveratrol, Nanosilver; Monolyth PEO and Zein vs. Core–shell PEO-Zein | Improved drug release with C-S system, Pathogen growth inhibition; Food packaging | [45] | |

| * C: None/Ethanol ** S: PCL, PEO (no zein)/Acetic acid | Coaxial | Tetracycline; Monolyth PCL vs. two Core–shell systems: Zein-PCL, Zein-PCL/PEO | Improved drug release with Zein-PCL, Better fibroblast adhesion comparatively to pristine PCL fibers; Wound dressing. | [46] | |

| None/Dimethylformamide | Uniaxial | Tetracycline loaded on graphene oxide particles (GO); | Improved drug release with GO; Wound dressing. | [47] | |

| PCL, Collagen/Chloroform, Ethanol | Uniaxial | Aloe vera, ZnO; Various Zein/PCL ratios | PCL improves blend performance, Antibacterial, Fibroblast adhesion, Sustained drug release; Wound dressing, Skin regeneration | [50] | |

| PEO/Ethanol | Uniaxial | Clove essential oil | Antibacterial in vitro; Wound dressing in situ on a mice model | [52] | |

| PVA/Ethanol | Uniaxial | Verapamil; PVA/Zein vs. PVA/Alginate | Sustained drug release better in PVA/Zein blend; Burn wound healing in vivo better with PVA/Alginate blend | [51] | |

| Polyvinyl-pyrrolidone/Ethanol | Uniaxial | Propranolol | Favorable drug release and cytotxicity in vitro, and mucosal drug delivery ex vivo | [49] | |

| None/Ethanol | Uniaxial on zein film | Gentamycin; Mulitlayer membrane system | Sustained drug release; Skin regeneration | [48] | |

| PCL, gum arabic (GA)/Acetic acid, Formic acid | Uniaxial | Various polymer ratios in Zein/PCL/GA blends | Presence of GA improves fibroblast adhesion and antibacterial properties; Skin regeneration | [56] | |

| * C: PEO (no Zein)/ Hexafluoroisopropanol ** S: PCL/Hexafluoroisopropanol | Coaxial on 3D zein/PLA platform | Curcumin, Tetracycline, β-glycerolphosphate | Sustained drug release; Periodontal tissue regeneration | [55] | |

| Gelatin/Acetic acid | Uniaxial | Glucose-crosslinked Zein/Gelatin blends as bone tissue scaffolds | Cranial bone regeneration in vivo improved with crosslinked polymers | [53] | |

| * C: PLA (no Zein)/Hexafluoroisopropanol ** S: None/Hexafluoroisopropanol | Coaxial | rhBMP2, Dexamethasone | Sustained drug release, Mesenchymal stem cell growth; Bone regeneration | [54] |

3.2. Soy Protein—Source and Properties

Biomedical Application of Electrospun Soy Protein

| Protein | Adjuvant Polymer/Solvent | Electrospinning Type | Drug, Bioactive Compound and/or Condition Tested | Biomedical Effects and Suggested Application of the Electrospun Material | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soy protein | Zein (Z), PEO/Acetic acid, Ethanol | Uniaxial | Ginger essential oil in SP/Z/PEO blend | Antibacterial; Food packaging | [65] |

| PVA/Acetic acid | Uniaxial | Plant essential oils in SP/Z/PEO blend | Antibacterial; Food packaging | [66] | |

| PCL/Acetic acid | Uniaxial | Tea tree oil in SP/PCL blend | Antibacterial and Fibroblast scratch test in vitro; Food packaging, Wound dressing | [71] | |

| PEO, Alginate (A)/Alkaline solution | Uniaxial | Vancomycin, SP/PEO/A blends vs. PEO/A blend | Improved drug release from blends with SP | [69] | |

| PVA/Alkaline solution | Uniaxial | Ketoprofen loaded on sepiolite, in SP/PVA blend | Improved drug release with nanocarriers | [72] | |

| Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC)/Water | Uniaxial | Diclofenac sodium loaded on halloysite nanotubes in SP/HEC blends | Improved wound dressing and drug release with nanocarriers | [73] | |

| * C: PEO, Alginate (A)/Alkaline solution ** S: PCL (no SP)/Dichloromethane, Dimethylformamide | Coaxial | Tetracycline; Monolyth SP/A/PEO vs. Core–shell system SP/A/PEO -PCL | Drug release improved with coaxial system; Biocompatibility in vitro; Wound dressing | [70] | |

| PEO/Alkaline solution | Uniaxial | Optimization of SP/PEO fiber morphology | Mesechymal stem cell proliferation; Tissue regeneration | [76] | |

| None/Buffer solution, SDS, Cysteine | Uniaxial | 2D vs. 3D cell scaffolds | Stability of 3D scaffolds, Mesechymal stem cells proliferation; Tissue regeneration | [77] | |

| SF/Formic acid | Uniaxial | SP/SF blends vs. pristine SP and SF, and casted SF discs | Better skin tissue regeneration in vitro and wound healing in vivo | [78] | |

| PEO/Water | Uniaxial, blow and standard electrospinning | SP/PEO fibers (blow electrosp.) vs. PCL fibers (stand. electrosp.) | Equal or better cell growth on SP/PEO; Retinal epithelium regeneration | [79] | |

| PLA/Hexafluoroisopropanol | Uniaxial, highly oriented | SP/PLA blends vs. pristine PLA; Different collectors | Superior peripheral nerves regeneration with SP/PLA conduits | [80] |

3.3. Wheat Gluten—Source and Properties

Biomedical Application of Electrospun Wheat Gluten

3.4. Other Plant Protein Sources

3.4.1. Legumes

3.4.2. Oil Crops

3.4.3. Tubers

3.4.4. Amaranth

4. Conclusions, Prospects and Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | amaranth protein |

| BP | bean protein |

| CP | canola protein |

| PCL | polycaprolactone |

| PEO | polyethylene oxide |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| PP | pea protein |

| PtP | potato protein |

| PVA | polyvinyl alcohol |

| SF | silk fibroin |

| SFP | sunflower protein |

| SP | soy protein |

| TP | taro protein |

| WG | wheat gluten |

References

- Niva, M.; Vainio, A. Towards more environmentally sustainable diets? Changes in the consumption of beef and plant- and insect-based protein products in consumer groups in Finland. Meat Sci. 2021, 182, 108635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Szymanowska, U.; Złotek, U.; Zielińska, E. Digestion and bioavailability of bioactive phytochemicals. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langyan, S.; Yadava, P.; Khan, F.N.; Dar, Z.A.; Singh, R.; Kumar, A. Sustaining Protein Nutrition Through Plant-Based Foods. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gençdağ, E.; Görgüç, A.; Yılmaz, F.M. Recent Advances in the Recovery Techniques of Plant-Based Proteins from Agro-Industrial By-Products. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 37, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojić, M.; Mišan, A.; Tiwari, B. Eco-innovative technologies for extraction of proteins for human consumption from renewable protein sources of plant origin. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Tomar, M.; Potkule, J.; Verma, R.; Punia, S.; Mahapatra, A.; Belwal, T.; Dahuja, A.; Joshi, S.; Berwal, M.K.; et al. Advances in the plant protein extraction: Mechanism and recommendations. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 115, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.H.C.S.; Vilela, C.; Marrucho, I.M.; Freire, C.S.R.; Pascoal Neto, C.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Protein-based materials: From sources to innovative sustainable materials for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Potential of plant proteins for medical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, A.; Kara, A.A.; Acartürk, F. Peptide-protein based nanofibers in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Mahmoodzadeh, F.; Yavari Maroufi, L.; Nezhad-Mokhtari, P. Electrospun tetracycline hydrochloride loaded zein/gum tragacanth/poly lactic acid nanofibers for biomedical application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1312–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabbaz, B.; Solouk, A.; Mirzadeh, H. Polyvinyl alcohol/soy protein isolate nanofibrous patch for wound-healing applications. Prog. Biomater. 2019, 8, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthil Muthu Kumar, T.; Senthil Kumar, K.; Rajini, N.; Siengchin, S.; Ayrilmis, N.; Varada Rajulu, A. A comprehensive review of electrospun nanofibers: Food and packaging perspective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 175, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barud, H.S.; De Sousa, F.B. Electrospun Materials for Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov Pereira da Cunha, M.D.; Caracciolo, P.C.; Abraham, G.A. Latest advances in electrospun plant-derived protein scaffolds for biomedical applications. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 18, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Jobaer, M.; Mahedi, S.I.; Ali, A. Protein–based electrospun nanofibers: Electrospinning conditions, biomedical applications, prospects, and challenges. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce Yardamici, A.; Tarhan, Ö. Electropsun Protein Nanofibers and Their Potential Food Applications. Mugla J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 6, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Vázquez, G.; Ortiz-Frade, L.; Figueroa-Cárdenas, J.D.; López-Rubio, A.; Mendoza, S. Electrospinnability study of pea (Pisum sativum) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) using the conformational and rheological behavior of their protein isolates. Polym. Test. 2020, 81, 106217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.C.; Stephansen, K.; Chronakis, I.S. Electrospinning of food proteins and polysaccharides. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetova, A.; Heinz, A. Electrospinning Proteins for Wound Healing Purposes: Opportunities and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2020, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman Mohammadi, M.; Rostami, M.R.; Raeisi, M.; Tabibi Azar, M. Production of Electrospun Nanofibers from Food Proteins and Polysaccharides and Their Applications in Food and Drug Sciences. Jorjani Biomed. J. 2018, 6, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, M.; Geerdink, P.; Brier, P.; van den Eijnden, P.; Henket, J.T.M.M.; Langelaan, M.L.P.; Stroeks, N.; van Deventer, H.C.; Martin, A.H. Reprint of “Food-grade electrospinning of proteins”. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014, 24, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, R.; Georgilis, E.; Bittner, A.M.; Gelmi, M.L.; Clerici, F. Peptide-based electrospun fibers: Current status and emerging developments. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Cui, S.; McClements, D.J.; Wu, X.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; Qiu, C.; et al. Preparation, Characteristics, and Advantages of Plant Protein-Based Bioactive Molecule Delivery Systems. Foods 2022, 11, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babitha, S.; Rachita, L.; Karthikeyan, K.; Shoba, E.; Janani, I.; Poornima, B.; Purna Sai, K. Electrospun protein nanofibers in healthcare: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 523, 52–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Kim, K. Electrospun polyacrylonitrile fibrous membrane for dust removal. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 973660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Giner, S.; Gimenez, E.; Lagaron, J.M. Characterization of the morphology and thermal properties of Zein Prolamine nanostructures obtained by electrospinning. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, C.Z.; Brudnicki, P.A.P.; Gong, Z.; Childs, H.R.; Lee, S.W.; Antrobus, R.M.; Fang, E.C.; Schiros, T.N.; Lu, H.H. Green electrospinning for biomaterials and biofabrication. Biofabrication 2021, 13, 035049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdraveva, E.; Mijovic, B. Frontier electrospun fibers for nanomedical applications. In Biotechnology—Biosensors, Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering; Intech Open: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, D.-G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.-N. Progress of Electrospun Nanofibrous Carriers for Modifications to Drug Release Profiles. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Huang, X.B.; Cai, X.M.; Lu, J.; Yuan, J.; Shen, J. The influence of fiber diameter of electrospun poly(lactic acid) on drug delivery. Fibers Polym. 2012, 13, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Yu, D.-G.; Liu, P. Elaborate design of shell component for manipulating the sustained release behavior from core–shell nanofibres. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Shukla, N.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Park, M.-H. Stimuli-Responsive Nanofibers Containing Gold Nanorods for On-Demand Drug Delivery Platforms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenberg, S.; Wahlgren, M.; Reslow, M.; Axelsson, A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 415, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reineccius, G.; Meng, Y. Gelatin and other proteins for microencapsulation. In Microencapsulation in the Food Industry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Hu, L.; Cai, T.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Q.; Yang, J.; Meng, C.; Hong, J. Purification and identification of two novel antioxidant peptides from perilla (Perilla frutescens L. Britton) seed protein hydrolysates. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortorella, S.; Maturi, M.; Vetri Buratti, V.; Vozzolo, G.; Locatelli, E.; Sambri, L.; Comes Franchini, M. Zein as a versatile biopolymer: Different shapes for different biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 39004–39026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, F. Zein-based nano-delivery systems for encapsulation and protection of hydrophobic bioactives: A review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 999373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Guzmán, C.J.; Castro-Muñoz, R. A Review of Zein as a Potential Biopolymer for Tissue Engineering and Nanotechnological Applications. Processes 2020, 8, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turasan, H.; Cakmak, M.; Kokini, J. A disposable ultrasensitive surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy biosensor platform fabricated from biodegradable zein nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.C.; Soares, J.C.; dos Santos, D.M.; Migliorini, F.L.; Popolin-Neto, M.; dos Santos Cinelli Pinto, D.; Carvalho, W.A.; Brandão, H.M.; Paulovich, F.V.; Correa, D.S.; et al. Nanoarchitectonic E-Tongue of Electrospun Zein/Curcumin Carbon Dots for Detecting Staphylococcus aureus in Milk. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 13721–13732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, Z.; Ghorani, B.; Emadzadeh, B.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Tucker, N. Protein-based halochromic electrospun nanosensor for monitoring trout fish freshness. Food Control 2020, 111, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, R.; Palakurthi, S. Zein in controlled drug delivery and tissue engineering. J. Control. Release 2014, 189, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Mateti, T.; Ramakrishna, S.; Laha, A. A Review on Curcumin-Loaded Electrospun Nanofibers and their Application in Modern Medicine. JOM 2022, 74, 3392–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrami-Hasan-Kohal, M.; Tayebi, L.; Ghorbani, M. Curcumin-loaded naturally-based nanofibers as active wound dressing mats: Morphology, drug release, cell proliferation, and cell adhesion studies. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 10343–10351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, P.; Song, W.; Wang, M.; Yu, D.-G. Electrospun Zein/Polyoxyethylene Core-Sheath Ultrathin Fibers and Their Antibacterial Food Packaging Applications. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Cai, J.; Schaedel, A.-L.; van der Plas, M.; Malmsten, M.; Rades, T.; Heinz, A. Zein-polycaprolactone core–shell nanofibers for wound healing. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 621, 121809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, H.; Ghaee, A.; Nourmohammadi, J.; Mashak, A. Electrospun zein/graphene oxide nanosheet composite nanofibers with controlled drug release as antibacterial wound dressing. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2020, 69, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimna, C.; Tamburaci, S.; Tihminlioglu, F. Novel zein-based multilayer wound dressing membranes with controlled release of gentamicin. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2019, 107, 2057–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendranath, M.; Ramesan, R.M.; Nair, P.; Parameswaran, R. Electrospun Mucoadhesive Zein/PVP Fibroporous Membrane for Transepithelial Delivery of Propranolol Hydrochloride. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Nezhad-Mokhtari, P.; Ramazani, S. Aloe vera-loaded nanofibrous scaffold based on Zein/Polycaprolactone/Collagen for wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, H.S.; Freag, M.S.; Gaber, S.M.; Al Oufy, A.; Abdallah, O.Y. Development of Verapamil Hydrochloride-loaded Biopolymer-based Composite Electrospun Nanofibrous Mats: In Vivo Evaluation of Enhanced Burn Wound Healing without Scar Formation. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 1211–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Mou, X.; Dong, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Dai, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, N.; Yan, X. In Situ Electrospinning Wound Healing Films Composed of Zein and Clove Essential Oil. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2020, 305, 1900790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. In vitro and in vivo assessment of glucose cross-linked gelatin/zein nanofibrous scaffolds for cranial bone defects regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2020, 108, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ma, Y.; Sun, D.; Ma, W.; Yao, J.; Zhang, M. Preparation and Characterization of Coaxial Electrospinning rhBMP2-Loaded Nanofiber Membranes. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019, 8106985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.M.; de Annunzio, S.R.; Carmello, J.C.; Pavarina, A.C.; Fontana, C.R.; Correa, D.S. Combining Coaxial Electrospinning and 3D Printing: Design of Biodegradable Bilayered Membranes with Dual Drug Delivery Capability for Periodontitis Treatment. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram Rad, Z.; Mokhtari, J.; Abbasi, M. Fabrication and characterization of PCL/zein/gum arabic electrospun nanocomposite scaffold for skin tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 93, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Venkateshan, K.; Mo, X.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.S. Physicochemical Properties of Soy Protein: Effects of Subunit Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9958–9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H. Nanostructured soy proteins: Fabrication and applications as delivery systems for bioactives (a review). Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 91, 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Netravali, A.N.; Joo, Y.L. Mechanical properties and biodegradability of electrospun soy protein Isolate/PVA hybrid nanofibers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sett, S.; Lee, M.W.; Weith, M.; Pourdeyhimi, B.; Yarin, A.L. Biodegradable and biocompatible soy protein/polymer/adhesive sticky nano-textured interfacial membranes for prevention of esca fungi invasion into pruning cuts and wounds of vines. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 2147–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirugnanaselvam, M.; Gobi, N.; Arun Karthick, S. SPI/PEO blended electrospun martrix for wound healing. Fibers Polym. 2013, 14, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Lugo, A.-C.; Lim, L.-T. Controlled release of allyl isothiocyanate using soy protein and poly(lactic acid) electrospun fibers. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stie, M.B.; Kalouta, K.; da Cunha, C.F.B.; Feroze, H.M.; Vetri, V.; Foderà, V. Sustainable strategies for waterborne electrospinning of biocompatible nanofibers based on soy protein isolate. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 34, e00519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzli, I.; Gibis, M.; Baier, S.K.; Weiss, J. Electrospinning of whey and soy protein mixed with maltodextrin—Influence of protein type and ratio on the production and morphology of fibers. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.T.; da Cunha, K.F.; Fonseca, L.M.; Antunes, M.D.; El Halal, S.L.M.; Fiorentini, Â.M.; Zavareze, E.d.R.; Dias, A.R.G. Action of ginger essential oil (Zingiber officinale) encapsulated in proteins ultrafine fibers on the antimicrobial control in situ. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeisi, M.; Mohammadi, M.A.; Bagheri, V.; Ramezani, S.; Ghorbani, M.; Tabibiazar, M.; Coban, O.E.; Khoshbakht, R.; Marashi, S.M.H.; Noori, S.M.A. Fabrication of Electrospun Nanofibres of Soy Protein Isolate/Polyvinyl Alcohol Embedded with Cinnamon Zeylanicum and Zataria Multiflora Essential Oils and their Antibacterial Effect. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13, 486. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.Y.; Chaudhry, M.A.; Kennard, M.L.; Jardon, M.A.; Braasch, K.; Dionne, B.; Butler, M.; Piret, J.M. Fed-batch CHO cell t-PA production and feed glutamine replacement to reduce ammonia production. Biotechnol. Prog. 2013, 29, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Yan, G.; Marquez, S.; Andler, S.; Dersjant-Li, Y.; de Mejia, E.G. Molecular size and immunoreactivity of ethanol extracted soybean protein concentrate in comparison with other products. Process Biochem. 2020, 96, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkanya, R.; Chuysinuan, P.; Pengsuk, C.; Techasakul, S.; Lirdprapamongkol, K.; Svasti, J.; Nooeaid, P. Electrospinning of alginate/soy protein isolated nanofibers and their release characteristics for biomedical applications. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2017, 2, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuysinuan, P.; Pengsuk, C.; Lirdprapamongkol, K.; Techasakul, S.; Svasti, J.; Nooeaid, P. Enhanced Structural Stability and Controlled Drug Release of Hydrophilic Antibiotic-Loaded Alginate/Soy Protein Isolate Core-Sheath Fibers for Tissue Engineering Applications. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustdar, F.; Ramezani, S.; Ghorbani, M.; Mortazavi Moghadam, F. Optimization and characterization of a novel tea tree oil-integrated poly (ε-caprolactone)/soy protein isolate electrospun mat as a wound care system. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 627, 122218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutschmidt, D.; Hazra, R.S.; Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; Sabzi, M.; Jiang, L. Electrospun, sepiolite-loaded poly(vinyl alcohol)/soy protein isolate nanofibers: Preparation, characterization, and their drug release behavior. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 594, 120172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Sarwar, M.N.; Wang, F.; Kharaghani, D.; Sun, L.; Zhu, C.; Yoshiko, Y.; Mayakrishnan, G.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, I.S. In vitro biocompatibility, antibacterial activity, and release behavior of halloysite nanotubes loaded with diclofenac sodium salt incorporated in electrospun soy protein isolate/hydroxyethyl cellulose nanofibers. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Dai, S.; Huang, J.; Hu, X.; Ge, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, K.; Shao, P.; Sun, P.; Xiang, N. Soy Protein Amyloid Fibril Scaffold for Cultivated Meat Application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 15108–15119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, C.; Gleddie, S.; Xiao, C.-W. Soybean Bioactive Peptides and Their Functional Properties. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramji, K.; Shah, R.N. Electrospun soy protein nanofiber scaffolds for tissue regeneration. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 29, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cai, S.; Sellers, A.; Yang, Y. Intrinsically water-stable electrospun three-dimensional ultrafine fibrous soy protein scaffolds for soft tissue engineering using adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 15451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, N.; Sahi, A.K.; Poddar, S.; Mahto, S.K. Soy protein isolate supplemented silk fibroin nanofibers for skin tissue regeneration: Fabrication and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, M.A.; Kruczek, K.; Wilson, J.H.; Brooks, M.J.; Drinnan, C.T.; Regent, F.; Gerstenhaber, J.A.; Swaroop, A.; Lelkes, P.I.; Li, T. Soy Protein Nanofiber Scaffolds for Uniform Maturation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2020, 26, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tong, Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Ren, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, P.; He, X.; Chen, P.; Chen, Y. Aligned soy protein isolate-modified poly(L-lactic acid) nanofibrous conduits enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Neural Eng. 2020, 17, 036003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y. Wheat gluten–based coatings and films: Preparation, properties, and applications. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerdeman, D.L.; Ye, P.; Shenoy, S.; Parnas, R.S.; Wnek, G.E.; Trofimova, O. Electrospun Fibers from Wheat Protein: Investigation of the Interplay between Molecular Structure and the Fluid Dynamics of the Electrospinning Process. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Enríquez, D.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Ramírez-Wong, B.; Torres-Chávez, P.; Castillo-Ortega, M.; Rodríguez-Félix, D.; Armenta-Villegas, L.; Ledesma-Osuna, A. Preparation, Characterization and Release of Urea from Wheat Gluten Electrospun Membranes. Materials 2012, 5, 2903–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandayuthapani, B.; Mallampati, R.; Sriramulu, D.; Dsouza, R.F.; Valiyaveettil, S. PVA/Gluten Hybrid Nanofibers for Removal of Nanoparticles from Water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubasova, D.; Mullerova, J.; Netravali, A.N. Water-resistant plant protein—Based nanofiber membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Asandei, A.D.; Parnas, R.S. Aqueous electrospinning of wheat gluten fibers with thiolated additives. Polymer 2010, 51, 3164–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, F.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Hall, S.; Kuktaite, R. Innovative Green Way to Design Biobased Electrospun Fibers from Wheat Gluten and These Fibers’ Potential as Absorbents of Biofluids. ACS Environ. Au 2022, 2, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.M.D.; Patzer, V.L.; Dersch, R.; Wendorff, J.; da Silveira, N.P.; Pranke, P. A novel globular protein electrospun fiber mat with the addition of polysilsesquioxane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhong, H.; Pan, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Superior water stability and antimicrobial activity of electrospun gluten nanofibrous films incorporated with glycerol monolaurate. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 109, 106116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhong, H.; Zou, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Impact of glycation on physical properties of composite gluten/zein nanofibrous films fabricated by blending electrospinning. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Hosseinzadeh, L.; Arkan, E.; Azandaryani, A.H. Preparation of electrospun nanofibers based on wheat gluten containing azathioprine for biomedical application. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2019, 68, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shao, W.; Luo, M.; Bian, J.; Yu, D.-G. Electrospun Blank Nanocoating for Improved Sustained Release Profiles from Medicated Gliadin Nanofibers. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, B.P.; Senaratne-Lenagala, L.; Stube, A.; Brackenridge, A. Protein demand: Review of plant and animal proteins used in alternative protein product development and production. Anim. Front. 2020, 10, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.X.; He, J.F.; Zhang, Y.C.; Bing, D.J. Composition, physicochemical properties of pea protein and its application in functional foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2593–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maftoonazad, N.; Shahamirian, M.; John, D.; Ramaswamy, H. Development and evaluation of antibacterial electrospun pea protein isolate-polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite mats incorporated with cinnamaldehyde. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 94, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.W.; Qin, Z.Y.; Xu, J.X.; Kong, B.H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Preparation and characterization of pea protein isolate-pullulan blend electrospun nanofiber films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzli, I.; Griener, D.; Gibis, M.; Schmid, C.; Dawid, C.; Baier, S.K.; Hofmann, T.; Weiss, J. Influence of Maillard reaction conditions on the formation and solubility of pea protein isolate-maltodextrin conjugates in electrospun fibers. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OuYang, Q.; Duan, X.; Li, L.; Tao, N. Cinnamaldehyde Exerts Its Antifungal Activity by Disrupting the Cell Wall Integrity of Geotrichum citri-aurantii. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.; Cal, R.; Casey, R.; Lopez, C.; Adelfio, A.; Molloy, B.; Wall, A.M.; Holton, T.A.; Khaldi, N. The anti-ageing effects of a natural peptide discovered by artificial intelligence. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2020, 42, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Mendoza-Díaz, S.; Loarca-Piña, G. Functional and technological potential of dehydrated Phaseolus vulgaris L. flours. Food Chem. 2014, 161, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, N.F.; Koocheki, A.; Varidi, M.; Kadkhodaee, R. Introducing Speckled sugar bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) protein isolates as a new source of emulsifying agent. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Gao, Y.; Chen, F.; Du, Y. Preparation and properties of electrospun peanut protein isolate/poly-l-lactic acid nanofibers. LWT 2022, 153, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Rempel, C.; Wanasundara, J. Canola/Rapeseed Protein: Future Opportunities and Directions—Workshop Proceedings of IRC 2015. Plants 2016, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasundara, J.P.D. Proteins of Brassicaceae Oilseeds and their Potential as a Plant Protein Source. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 635–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-M.; Li, Y.; Ma, H.; He, R. Effects of ultrasonic-assisted pH shift treatment on physicochemical properties of electrospinning nanofibers made from rapeseed protein isolates. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 94, 106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod, K.; Ansari, S.H.; Ali, J. Eugenol: A Natural Compound with Versatile Pharmacological Actions. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1934578X1000501236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanesazzadeh, E.; Kadivar, M.; Fathi, M. Production and characterization of hydrophilic and hydrophobic sunflower protein isolate nanofibers by electrospinning method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waglay, A.; Karboune, S. Potato Proteins. In Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- SHEWRY, P.R. Tuber Storage Proteins. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardhani, R.A.K.; Asri, L.A.T.W.; Rachmawati, H.; Khairurrijal, K.; Purwasasmita, B.S. Physical–Chemical Crosslinked Electrospun Colocasia esculenta Tuber Protein–Chitosan–Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Nanofibers with Antibacterial Activity and Cytocompatibility. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 6433–6449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibis, M.; Pribek, F.; Weiss, J. Effects of Electrospun Potato Protein–Maltodextrin Mixtures and Thermal Glycation on Trypsin Inhibitor Activity. Foods 2022, 11, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibis, M.; Pribek, F.; Kutzli, I.; Weiss, J. Influence of the Protein Content on Fiber Morphology and Heat Treatment of Electrospun Potato Protein–Maltodextrin Fibers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Pauly, A.; Rombouts, I.; Jansens, K.J.A.; Deleu, L.J.; Delcour, J.A. Proteins of Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.), Buckwheat (Fagopyrum spp.), and Quinoa (Chenopodium spp.): A Food Science and Technology Perspective. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno-Medina, M.; Mendoza, S.; Lagaron, J.M.; López-Rubio, A. Development and characterization of food-grade electrospun fibers from amaranth protein and pullulan blends. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Padilla, A.; López-Rubio, A.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Mendoza, S. Characterization, release and antioxidant activity of curcumin-loaded amaranth-pullulan electrospun fibers. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno-Medina, M.; Mendoza, S.; Rodríguez, B.A.; Lagaron, J.M.; López-Rubio, A. Improved antioxidant capacity of quercetin and ferulic acid during in-vitro digestion through encapsulation within food-grade electrospun fibers. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, K.M.; Hernández-Iturriaga, M.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Luna-Bárcenas, G.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Mendoza, S. Stable nisin food-grade electrospun fibers. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3787–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, C.; Lv, S.; Ren, F.; Wang, J. Study on electrospinning of wheat gluten: A review. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, M.; Khatri, Z.; El-Ghazali, S.; Hussain, N.; Qureshi, U.A.; Kobayashi, S.; Ahmed, F.; Kim, I.S. Zein nanofibers via deep eutectic solvent electrospinning: Tunable morphology with super hydrophilic properties. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protein | Adjuvant Polymer/Solvent | Electrospinning Type | Drug, Bioactive Compound and/or Condition Tested | Biomedical Effects and Suggested Application of the Electrospun Material | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat gluten | None/Buffer solution, SDS | Uniaxial | Using non-reducing solvents | Improved absorption of biofluids | [87] |

| None/Acetic acid | Uniaxial | Glycerol monolaurate in WG | Antibacterial in vitro, Food packaging | [90] | |

| None/Acetic acid, Alcohols, Acetone | Uniaxial | Urea in WG | Wound healing | [83] | |

| PVA/Acetic acid, Ethanol, 2-Propanol | Uniaxial | Azathioprine in WG/PVA blend | Drug release | [91] | |

| * C: None/ Hexafluoroisopropanol ** S: None/ Trifluoroacetic acid, Hexafluoroisopropanol | Coaxial | Ketoprofen (K); Monolyth Gliadin/K vs. Core–shell Gliadin/K-Gliadin | Drug release improved with coaxial system | [92] |

| Protein | Adjuvant Polymer/Solvent | Electrospinning Type | Drug, Bioactive Compound and/or Condition Tested | Biomedical Effects and Suggested Application of the Electrospun Material | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea protein | PVA/Alkaline and Acidic solutions | Uniaxial | Cinnamaldehyde in PP/PVA blend | Antibacterial food packaging | [95] |

| Canola protein | PEO/Water | Uniaxial | Clove essential oil | Antibacterial packaging | [105] |

| Taro protein | PEO, Chitosan/Acetic acid | Uniaxial | Crosslinking with glutaraldehyde and heat treatment | Antibacterial; Skin fibroblast growth supporting; Wound healing | [110] |

| Amaranth protein | Pullulan (P)/Formic acid | Uniaxial | Curcumin, Quercetin and Ferulic acid in AP/P blends | Drug release upon digestion in vitro | [115,116] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zdraveva, E.; Gaurina Srček, V.; Kraljić, K.; Škevin, D.; Slivac, I.; Obranović, M. Agro-Industrial Plant Proteins in Electrospun Materials for Biomedical Application. Polymers 2023, 15, 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15122684

Zdraveva E, Gaurina Srček V, Kraljić K, Škevin D, Slivac I, Obranović M. Agro-Industrial Plant Proteins in Electrospun Materials for Biomedical Application. Polymers. 2023; 15(12):2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15122684

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdraveva, Emilija, Višnja Gaurina Srček, Klara Kraljić, Dubravka Škevin, Igor Slivac, and Marko Obranović. 2023. "Agro-Industrial Plant Proteins in Electrospun Materials for Biomedical Application" Polymers 15, no. 12: 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15122684

APA StyleZdraveva, E., Gaurina Srček, V., Kraljić, K., Škevin, D., Slivac, I., & Obranović, M. (2023). Agro-Industrial Plant Proteins in Electrospun Materials for Biomedical Application. Polymers, 15(12), 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15122684