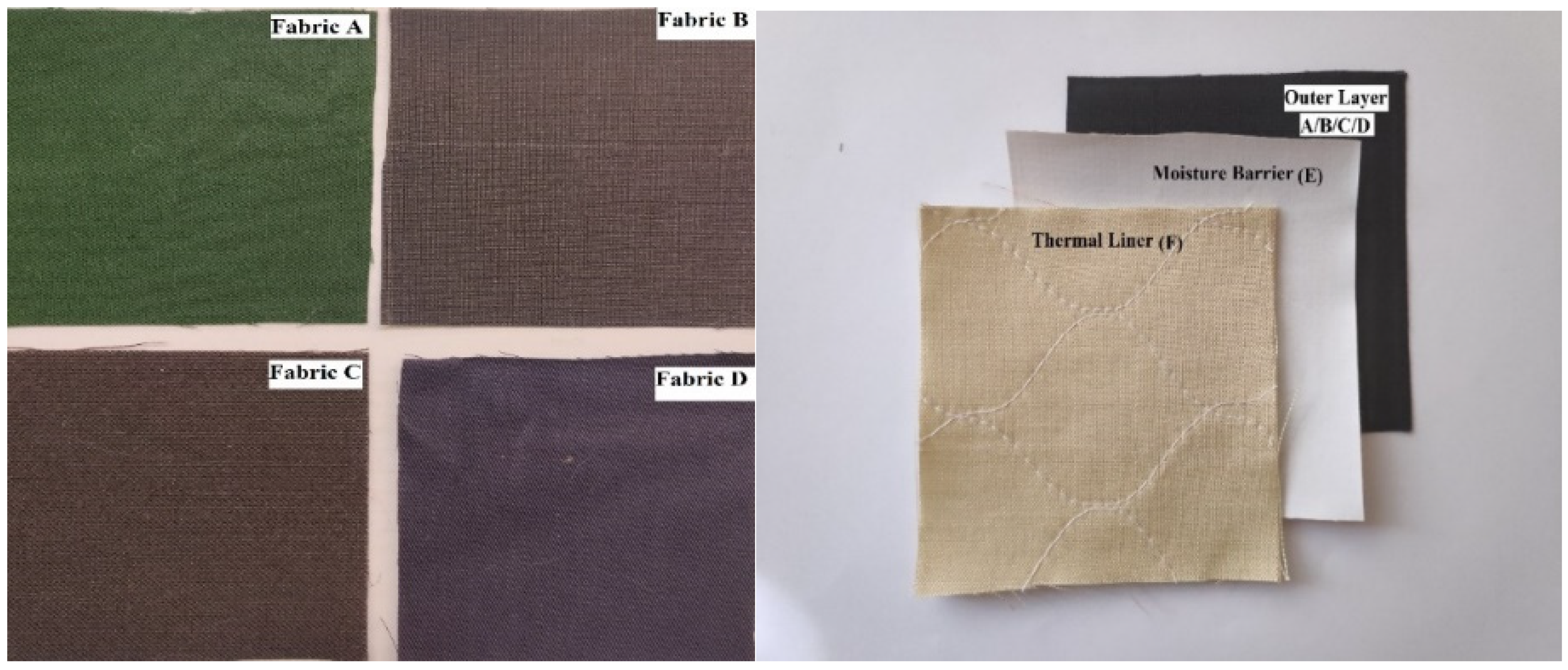

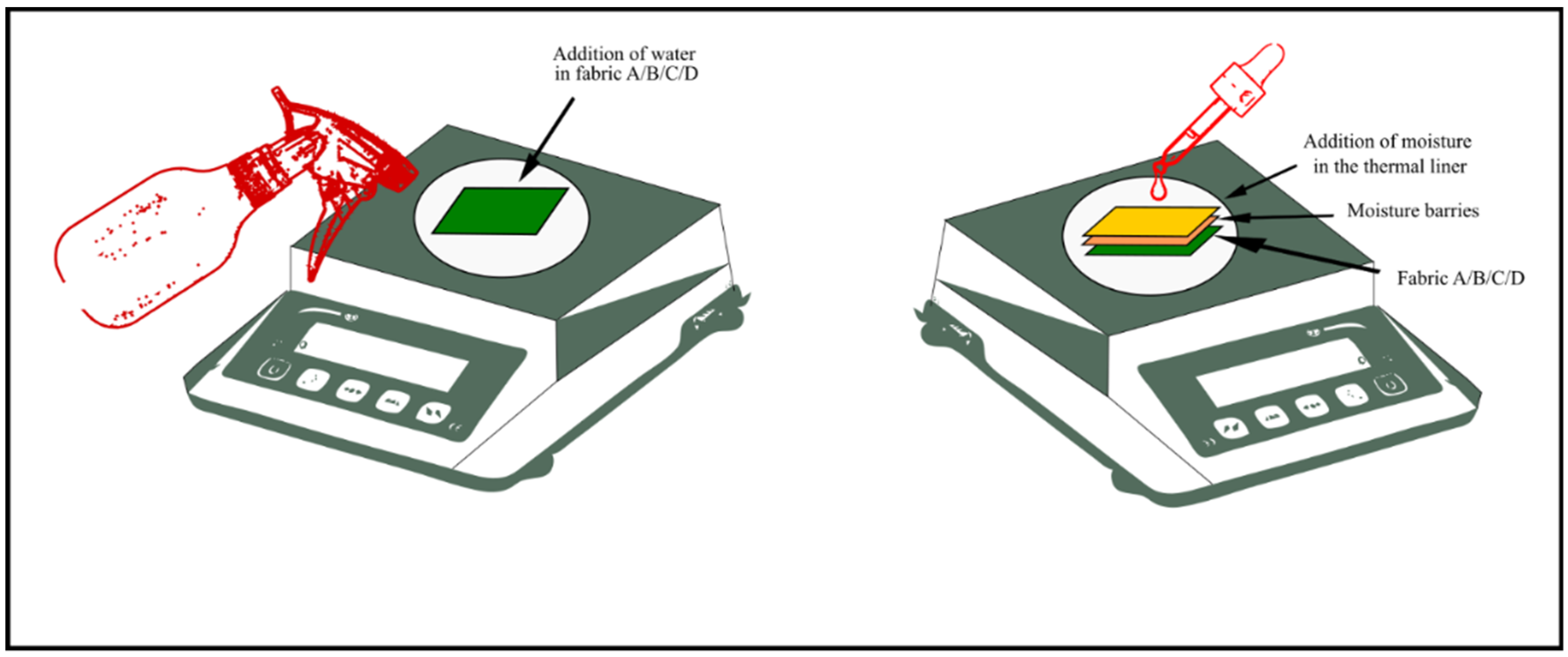

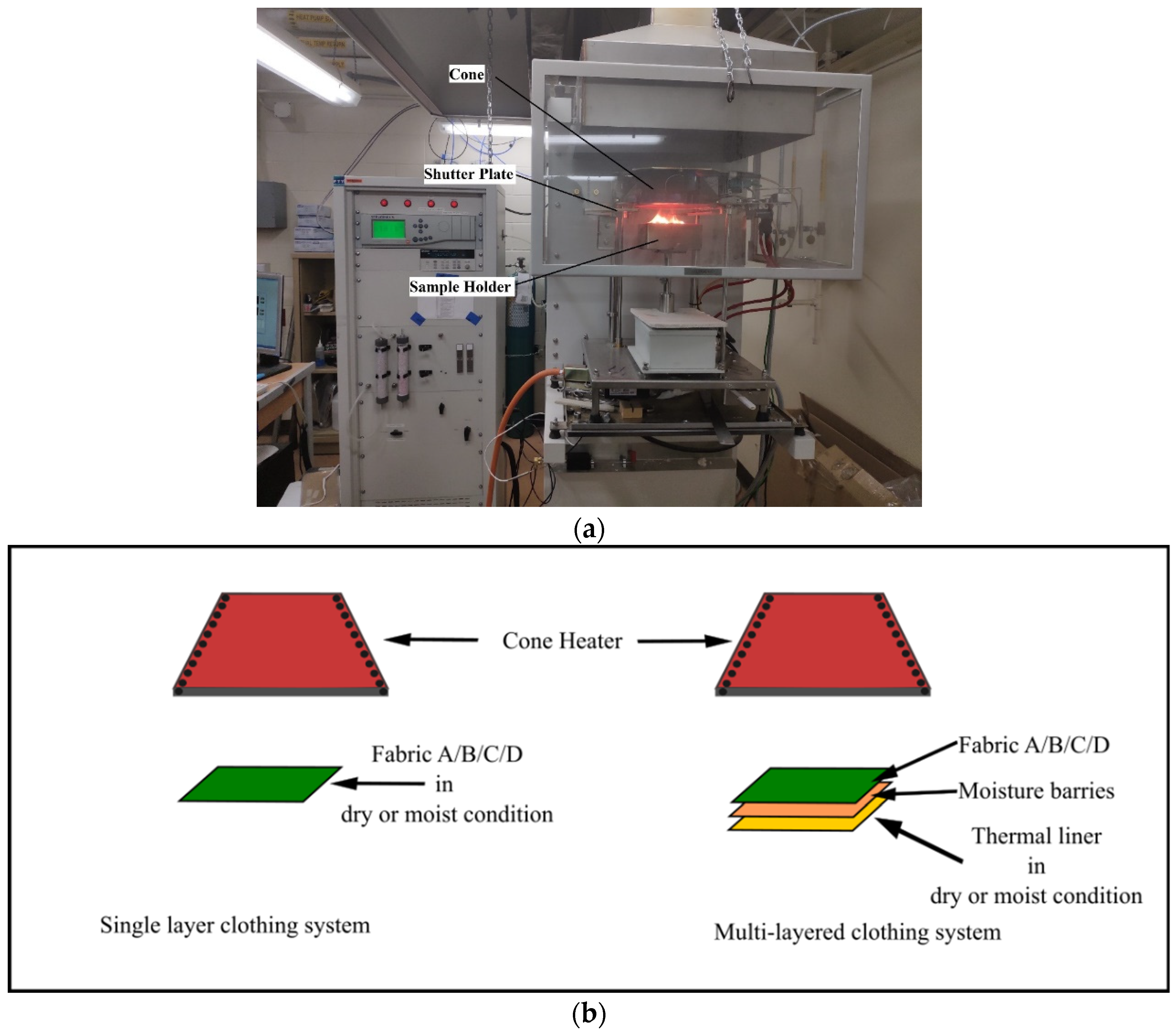

Section 3 are divided into three sub-sections. In

Section 3.1, change of tensile strength of the fabrics A, B, C, and D in the dry condition is discussed. In

Section 3.2, the tensile strength change of the fabrics A, B, C, and D is discussed while only single layer fabrics were exposed with moisture. In

Section 3.3, changes of tensile strength of the outer layers in three-layered fabric systems are discussed while the fabric system was exposed with moisture in the thermal liner. The radiant heat-treated fabrics were conditioned for 24 h before measuring the tensile strength. The tensile strength (warp direction) of the fabrics A, B, C, and D were measured by the tensile strength tester using the standard method ASTM D5034.

3.1. Effect of Radiant Heat on Tensile Strength of the Fabrics in Dry Condition

The initial strength of the fabric usually depends on the fabric and yarn properties, such as count, twist, ends and picks per inch, cover factor, weave structure, etc., and the type of fiber present in the fabric [

45,

46,

47,

48,

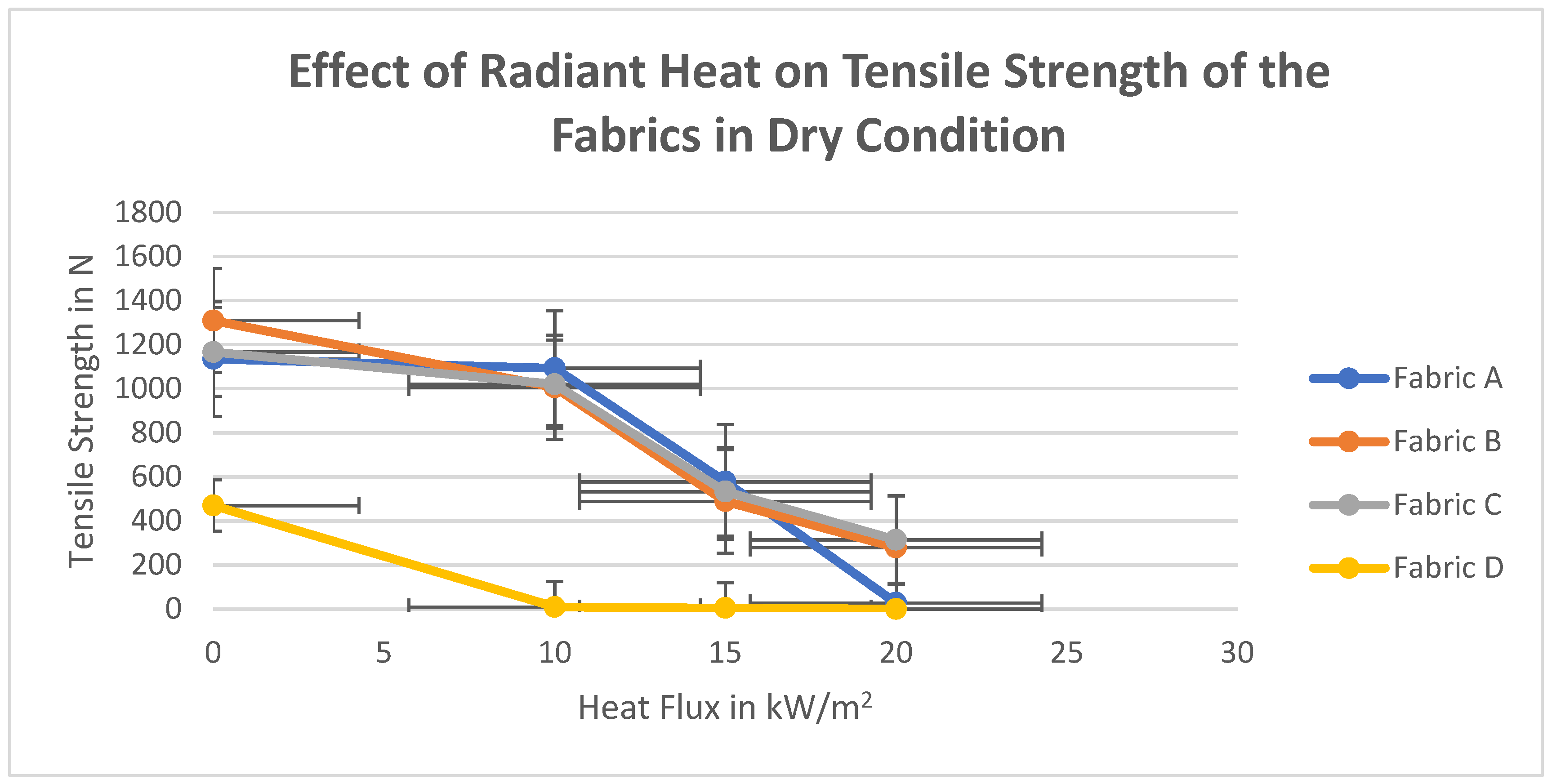

49]. The summary of the radiant heat on tensile strength summarizes in

Table 3. Since three of the experimented fabrics (A, B, and C) were made from synthetic fiber and fabric D was made from a natural fiber, the initial tensile strength of these two categories of fabrics was significantly different. In addition, the changing behavior of tensile strength after the radiant heat exposure also can be categorized into two groups. fabrics A, B, C behave similarly compared to fabric D, which behaved completely differently. In dry conditions, the level of radiant heat flux for an exposure time of five minutes has a significant (

p < 0.05) effect on the tensile strengths of the fabric used (

Table 3). In these five minutes of exposure, with the increase in heat flux intensity, the strength of the fabrics decreased. The loss of strength was higher at 15 and 20 kW/m

2 heat flux compared to the 10 kW/m

2 heat flux. Minimum loss of strength was around 50% and 75% at 15 kW/m

2 and 20 kW/m

2 heat flux, respectively, which was only around 4% at 10 kW/m

2. All four fabrics showed a similar trend of strength loss, only strength loss of fabric D was severe compared to the others. The difference between fabric D the fabrics A, B, and C is due to the type of fiber present in the fabrics. In general, natural fibers have lower strength compared to synthetic fibers [

50]. The tensile strength mostly depends on the crystallinity and spiral angle of the polymers. Higher crystallinity and lower spiral angle in general give higher strength [

51]. Usually, cotton has a lower crystallinity than synthetic fibers, moreover, the spiral angle of the polymers in cotton fiber is around or more than 20 degrees [

51,

52].

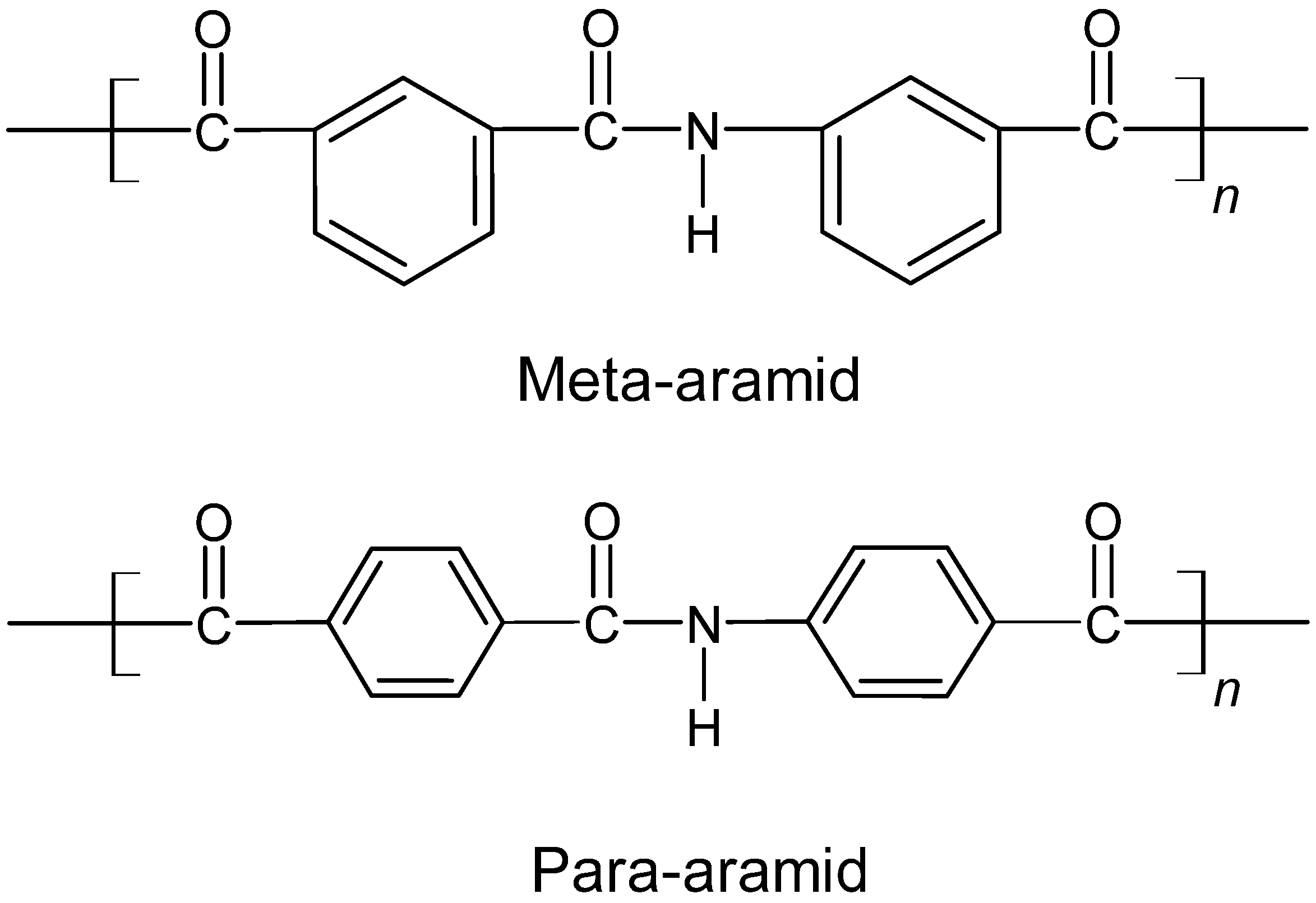

The tensile strength loss of fabric A was much higher at 20 kW/m

2 compared to fabrics B and C. The reason that Fabric B and C showed higher resistance in tensile strength loss compared to fabric A lies in their polymer structure. The fabric B and C which is made from para-aramid blend fiber connects at the para-position of the phenyl link, whereas the fabric A meta-aramid fibers connect at the meta-position. Therefore, polymers in para-aramid fiber are highly compact compared to the meta-aramid fibers [

53,

54]. Due to the lower compactness of the meta-aramid fiber compared to the para-aramid fiber, the meta-aramid fiber is not as strong as para-aramid fiber and is also more flexible than the para-aramid fiber [

53,

54].

Figure 5 shows the polymer structure of both meta-aramid and para-aramid fibers.

Effect of radiant heat exposure in dry condition on tensile strength of all four outer layers has been illustrated in

Figure 6.

The tensile strength of the fabric is mostly dependent on the organization of the polymer chains and the macrostructure [

55,

56,

57]. A similar pattern of loss of tensile strength with increased temperature is observed from

Figure 6. The loss of tensile strength can be explained due to the fibrillar to the lamellar transformations within the fibers which cause an increase in crystallinity with lamellar spacing [

58]. A linear regression analysis tool has been used to find out the R square and

t-test (

t and

p) values. As mentioned earlier, data have been grouped into three categories. In the first category, the tensile strength of four high-performance fabrics exposed in three different heat flux in dry conditions have been analyzed. Independent variables: (i) fabric properties (Weight/unit length, thickness, fabric count); (ii) heat flux intensities (10, 15, and 20 kW/m

2) are the ordinal variables. Dependent variable: tensile strength of the fabrics A, B, C, and D. The results are as shown in

Table 4.

The

t-test value matches the earlier discussion. The negative

t value of the heat intensity levels indicated that an increase in heat flux reduces the tensile strength of the fabric. The

p-value suggests the significance of the effect on tensile strength. From the R square values, it can be seen that thickness has the highest value compared to linear density and fabric count. Therefore, it can be said that thickness is the most important property while considering the tensile strength of the fabric [

59]. Fabric count seems the second most important property. Nevertheless, both thickness and fabric count moderately affect the tensile strength as their R square values are fairly high [

58,

60].

3.2. Effect of Moisture and Radiant Heat on Tensile Strength of Fabrics in Single Layer Fabric System

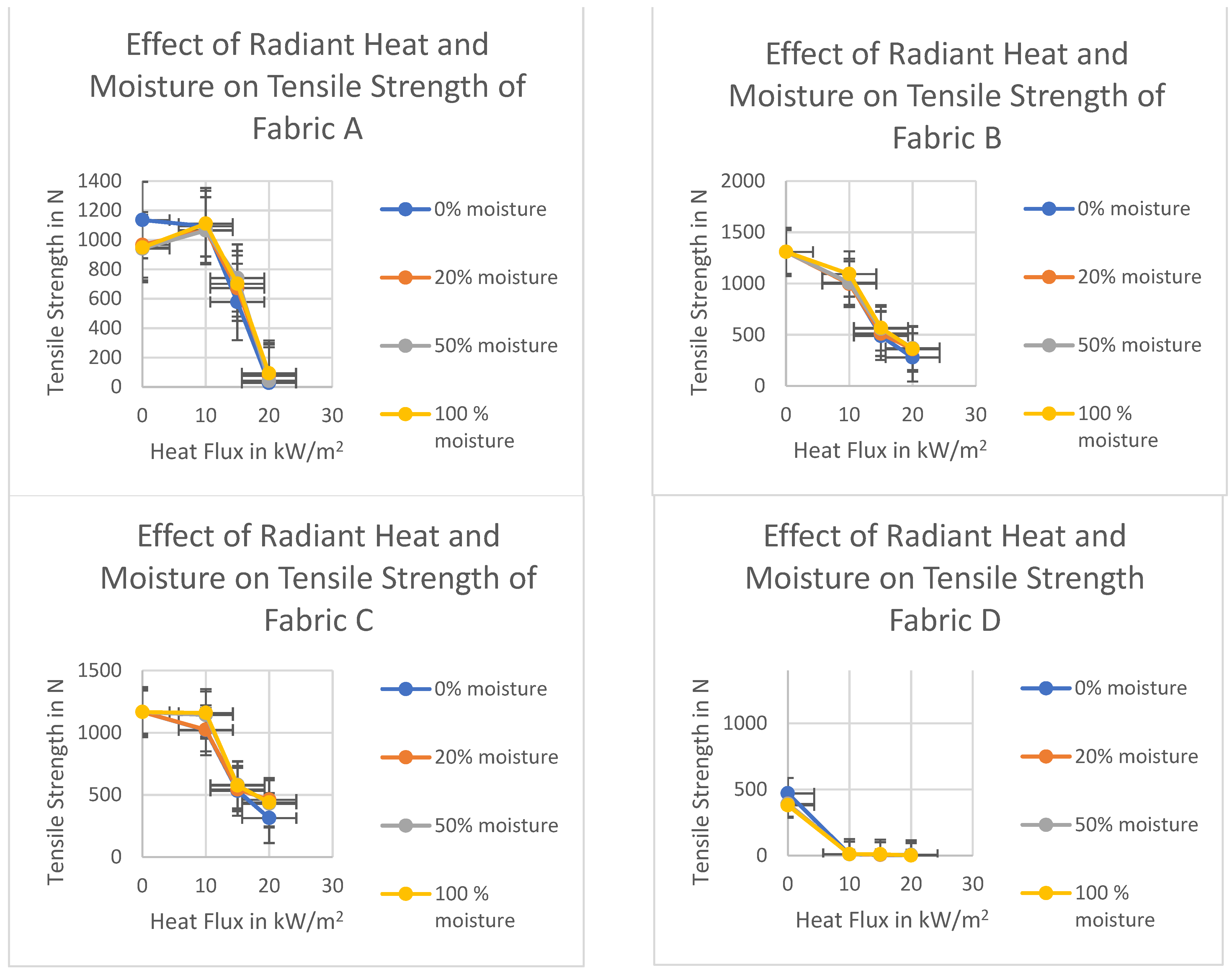

In the single-layer fabric system, moisture did not have much effect on the tensile strength of the fabrics (

Figure 7). The tensile strength of fabrics in the single-layer fabric system at both dry and moist conditions was almost similar. The addition of moisture in the single-layer fabric system slightly affected the tensile strength loss. This is because of the ease of evaporation of the water from the single-layer fabric. The moisture of the outer layer evaporated very quickly, which resulted in increased temperature in the fabric system, leading to the fabric to behave similarly to the dry fabric [

61]. The quick evaporation of the moisture results in the thermal degradation of the polymer chain. Since the moisture evaporated very quickly, the tensile strength of the moist fabric was almost like the dry fabric. A slightly improved tensile strength was shown at 10 kW/m

2 when the moisture percentage was 100%. The tensile strength of fabric A increased initially with respect to moisture during the heat exposure at 10 kW/m

2. This increasing tensile strength phenomenon could be explained based on the initial strength of fabric A in moist conditions. The initial tensile strength of fabric A in moist condition was lower than the dry condition. This is likely due to moisture reducing the friction between the fibers which resulted in lower tensile strength of the fabric in moist conditions before the heat exposure.

Multiple linear regression analysis tool has been used to determine the R square and

t-test value (

t and

p values). The independent and dependent variables are as follows: Independent variables: (i) Fabric Properties (Weight/unit length, thickness, fabric count); (ii) Heat flux intensities (0, 10, 15, and 20 kW/m

2), and moisture addition amount (0, 20, 50, and 100%) are the ordinal independent variables. Dependent variable: Tensile strength of the outer layer fabric. The results are shown in

Table 5. All four fabrics A, B, C, and D behaved almost similarly in both dry and moist conditions in single-layer fabric system. Only a very minor difference was seen when moisture addition was 100%.

In the single-layered fabric system, the moisture had no or minimal effect on the tensile strength. The statistical values also suggest a similar result. The

t-values for the moisture are positive and almost near zero. This suggests that moisture in the single-layer has a minimum effect on the tensile strength of the outer layer fabric. On the other hand, heat flux intensity has a similar negative effect on the

t-value. From the R square values, it can be seen that thickness has the highest value compared to linear density and fabric count. Therefore, it can be said that thickness is the most important property while considering the tensile strength of the fabric. Fabric count seems the second most important property. Nevertheless, both thickness and fabric count moderately affect the tensile strength as their R square values are fairly high. The summary of the effects of moisture and radiant heat in single-layer fabric system is shown in the table below (

Table 6).

3.3. Effect of Moisture and Radiant Heat on Tensile Strength of Outer Layer Fabrics in Three-Layered Fabric System

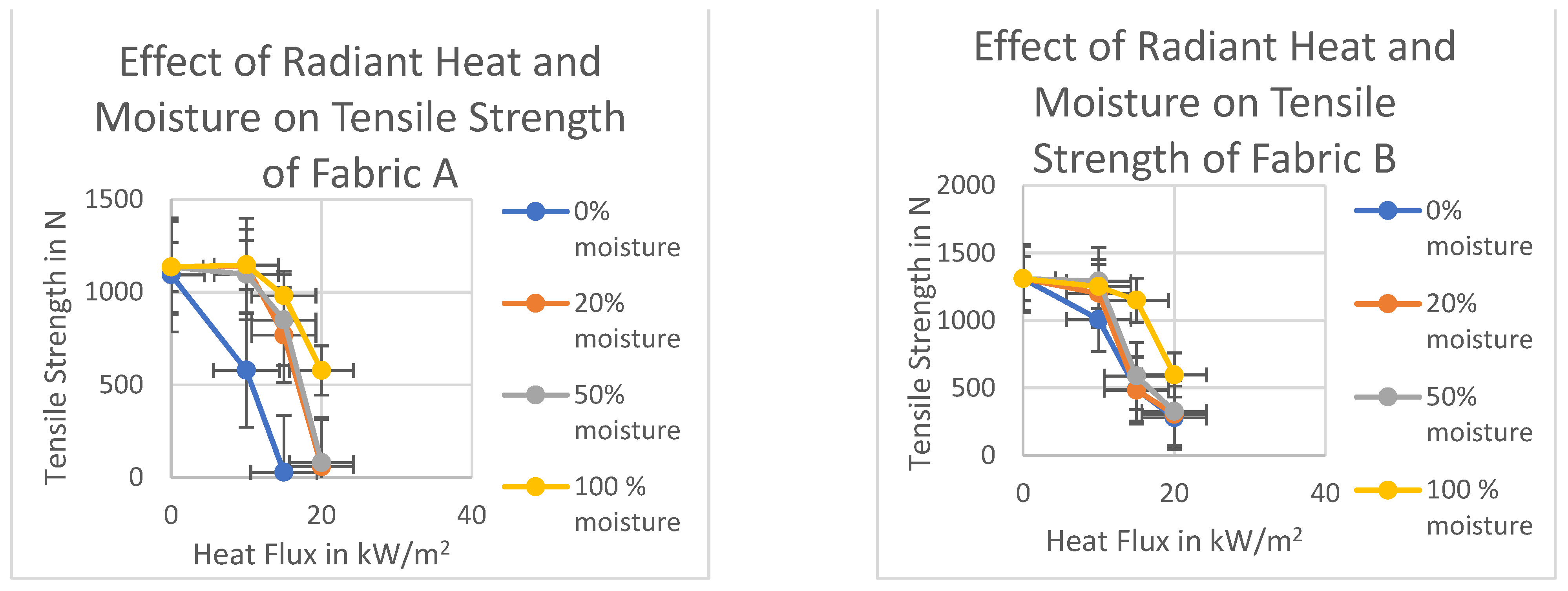

Added moisture had a significant (

p < 0.05) positive effect on the strength loss of the fabrics (

Figure 8). At a lower heat intensity level of 10 kW/m

2 and five minutes of exposure time, the tensile strength loss percentage was very low compared to the dry and single layer moist fabrics. No or minimum strength loss was seen for most of the fabrics at lower heat flux with the presence of moisture in the thermal liner. With the increase in heat flux, the effect of moisture decreased eventually. At 15 kW/m

2 heat flux 100% moisture showed the highest effect on the tensile strength loss. Only without the fabric D all other fabrics were able to retain most of their strength when exposed to 15 kW/m

2 heat flux for five minutes. The highest amount of strength loss was only 15%, which was around 60% at 15 kW/m

2 without moisture or the presence of moisture in the single layer.

At lower temperatures in the presence of moisture, there might be orientation changes of polymer chain occurred in some fabrics, which led to an increase in the crystalline region and increased the strength of the fiber. The strength loss was also lower at 15 kW/m

2 and 20 kW/m

2 in the presence of moisture compared to the dry fabrics for most of the fabrics. With moisture increasing, the strength loss percentage decreased. At higher heat flux, lower moisture content (20% and 50%) did not affect the tensile strength significantly. The moisture helped significantly to retain the tensile strength, especially at lower temperatures. The heat is absorbed in the process of transforming moisture into vapor. Since most of the heat energy has been used to evaporate the moisture the temperature inside of the exposed samples did not increase much [

62]. Therefore, the loss of tensile strength was considerably lower than dry and single layer moist conditions. The presence of moisture in the thermal liner could increase the heat capacity of the fabrics, which resulted in a significant amount of thermal energy storage within the fabric system [

6,

59,

63,

64].

Addition of moisture in the thermal liner had a significant positive effect on the tensile strength of fabrics A, B, and C, with only fabric D being the exception. This phenomenon is due to the type of fiber (i.e., natural or synthetic) present in the fabric, which has been discussed earlier. Added moisture had a significant effect on the strength loss of Fabric A. In wet condition, there is negligible amount of strength loss or slight gain in strength shown by this fiber. Tensile strength data show that the strength loss percentage was negative for 20% and 100% moisture addition. The strength loss was also significantly lower at 15 kW/m2 and 20 kW/m2 with the presence of moisture compared to the dry fabrics. With the increased moisture, the strength loss percentage decreased. The strength losses were 32%, 25%, and 14%, respectively, for 20%, 50%, and 100% moisture addition at 15 kW/m2. However, at the highest radiant flux at 20 kW/m2 the strength loss percentages were 95% and 93% for 20% and 50% moisture addition. At higher heat flux, lower moisture content (20% and 50%) did not affect the tensile strength significantly. However, at 100% moisture addition the heat loss percentage was only 49% which is half compared to 98% at the dry condition at 20 kW/m2. The 20% and 50% moisture addition had a very minor effect on the tensile strength at 15 and 20 kW/m2 in fabric B. The difference was below 10% at this moisture addition compared to the dry condition. However, the 100% moisture addition showed a significant effect even at higher heat flux. The tensile strength loss was 12% and 54% at 15 and 20 kW/m2, respectively, which were 63% and 79% for the same fabric in dry condition.

During the five minutes of exposure after the evaporation of the 20% and 50% added moisture maybe there was sufficient time to degrade the outer layer fabric. Therefore, this amount of moisture did not help the fabric retain its tensile strength by increasing the heat capacity of the fabric. However, the 100% moisture addition increased the heat capacity of the fabric to a certain level that the fabric to retain its strength, and therefore the tensile strength loss was lower at this moisture content. At lower radiant heat 10 kW/m

2 and with 20% moisture addition, the strength loss was 11% which was 13% at dry condition for the fabric C. Therefore, 20% moisture did not help significantly at lower heat flux. The increased heat capacity of the fabric for 20% moisture addition was not sufficient enough to retain the tensile strength during five minutes of exposure. However, for the 50% and 100% moisture addition, there was no loss or increase in the tensile strength (

Figure 8). Therefore, the amount of moisture can play a significant effect on the tensile strength at low radiant heat. At 20% and 50% moisture, there was no effect at 20 kW/m

2 heat exposure. The heat loss percentage was same for the 20% and 50% moisture while compared to the dry fabric. However, 100% moisture played a significant role at 20 kW/m

2. At a higher heat flux of 20 kW/m

2 this fabric behaved very differently compared to the other fabrics. The strength loss was lower at 20 kW/m

2 compared to the 15 kW/m

2. At 100% moisture content and 20 kW/m

2 radiant heat this fabric behaved similarly to the 50% moisture content and 10 kW/m

2 radiant heat exposure, which is a slight increase in tensile strength. Moisture played a significant role at higher heat flux 20 kW/m

2. The change of orientation of the polymer chains in presence of moisture could be the reason for this increase in strength. The strength loss decreased to 39% with 20% moisture addition which was 73% at dry conditions. This then comes down to 22% loss at 50% moisture, and then 3% increase at 100% moisture addition.

As discussed above, the least resistance to radiant heat exposure is shown by fabric D (

Figure 8). In dry condition, this fabric lost almost 100% of its strength even at 10 kW/m

2. The moisture had a positive effect only at the lower radiant heat exposure 10 kW/m

2. The tensile strength loss was 44% and 33%, respectively for 50% and 100% moisture content compared to the 98% at dry conditions. However, at higher heat flux 15 and 20 kW/m

2 moisture did not play any significant role. The strength loss of the moist fabrics at all percentages was similar to the dry fabrics. Moisture did not help much at higher temperatures because once the moisture evaporated the temperature inside the sample raised during five minutes of exposure [

65]. Fabric D loses its strength even at a lower heat flux of 10 kW/m

2. Therefore, at 15 and 20 kW/m

2 moisture could not help much in retaining the tensile strength. Once the moisture evaporated, the temperature increased, and fabric lost its tensile strength immediately. Multi-layer fabric system with the presence of moisture in the thermal liner during the exposure has been analyzed. Same linear regression analysis tool has been used to determine the R square and

t-test value (

t and

p values). The independent and dependent variables are as follows: Independent variables: (i) Fabric properties (Weight/unit length, thickness, fabric count); (ii) Heat flux intensities (0, 10, 15, and 20 kW/m

2) and moisture addition amount (0, 20, 50, and 100%) are the ordinal independent variables. Dependent variable: Tensile strength of the outer layer fabric. The results are shown in

Table 7.

From the earlier discussion, we have seen that in the three-layered fabric system with the presence of moisture in the thermal liner, moisture has positive effect on the tensile strength. On the other hand, the level of heat intensity has a negative effect on the tensile strength. The t-test value in the above table shows the same result. For all four outer layers, t-values for moisture have a positive value, and heat intensity values have a negative value. All the t-test values except fabric count are statistically significant when the alpha value is 0.1 or lower.

Additionally, the R

2 values of the multi-layer fabric system are lower compared to the single-layer fabric system. This suggests the moisture in the thermal liner plays crucial part in determining the effect on tensile strength of the fabrics compared to the presence of moisture in the single layer. Since moisture in the outer layer did not affect the tensile strength, the strength almost depended on the heat flux intensities solely. Therefore, the R square values are greater in the single-layered fabric system compared to the three-layered fabric system. Similar to the previous discussion, thickness is the most important property when we consider the fabric tensile strength. Similarly, fabric count is the second most important property. Nevertheless, both thickness and fabric count moderately affect the tensile strength as their R square values are fairly high.

Table 8 summarizes the combined effect of radiant heat and moisture on the tensile strength of all four outer layer fabrics.