Improved Hydrogen Separation Using Hybrid Membrane Composed of Nanodiamonds and P84 Copolyimide

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. P84/ND Composite Preparation

2.3. Membrane Formation

2.4. Characterization of P84 and P84/ND

2.5. Gas Permeation Measurement

3. Results

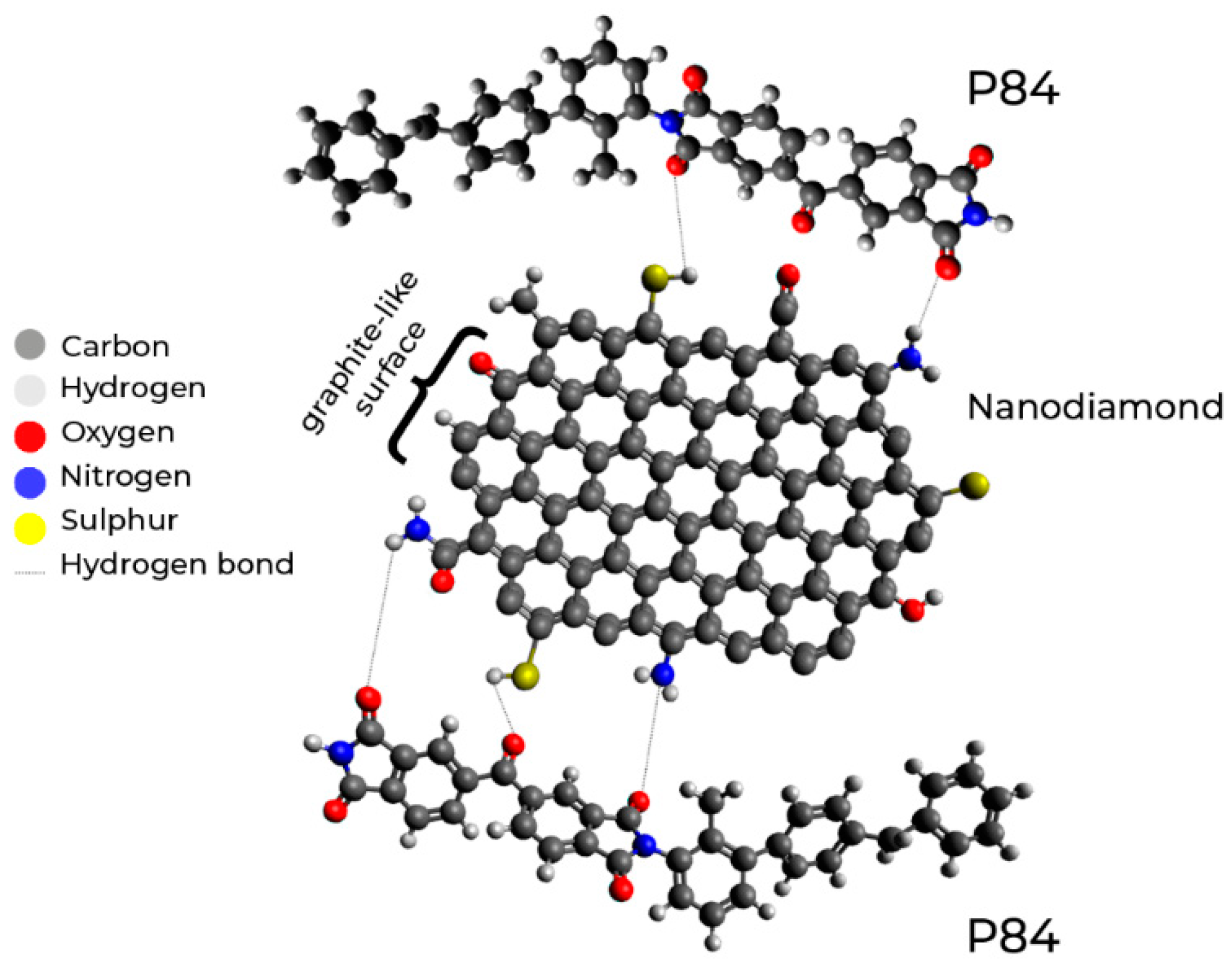

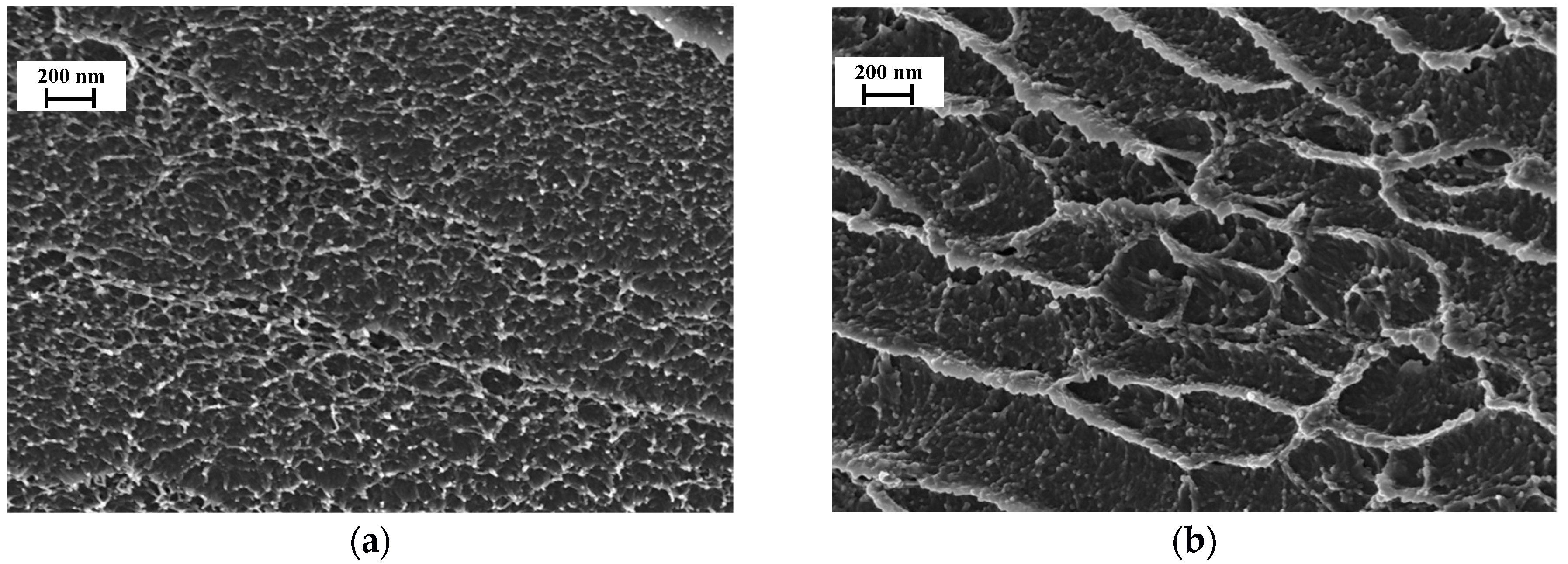

3.1. Membrane Structure

3.2. Physical Properties

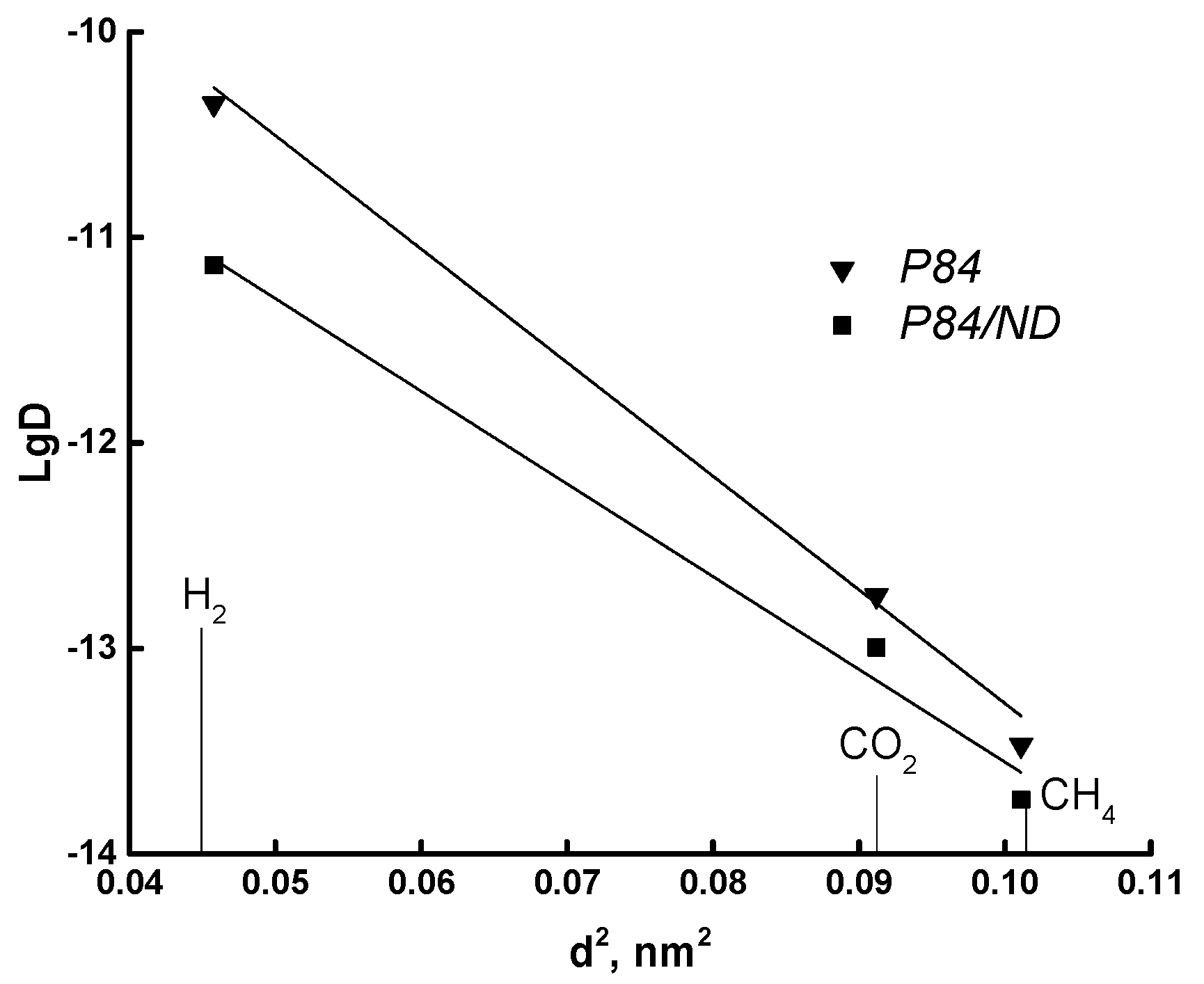

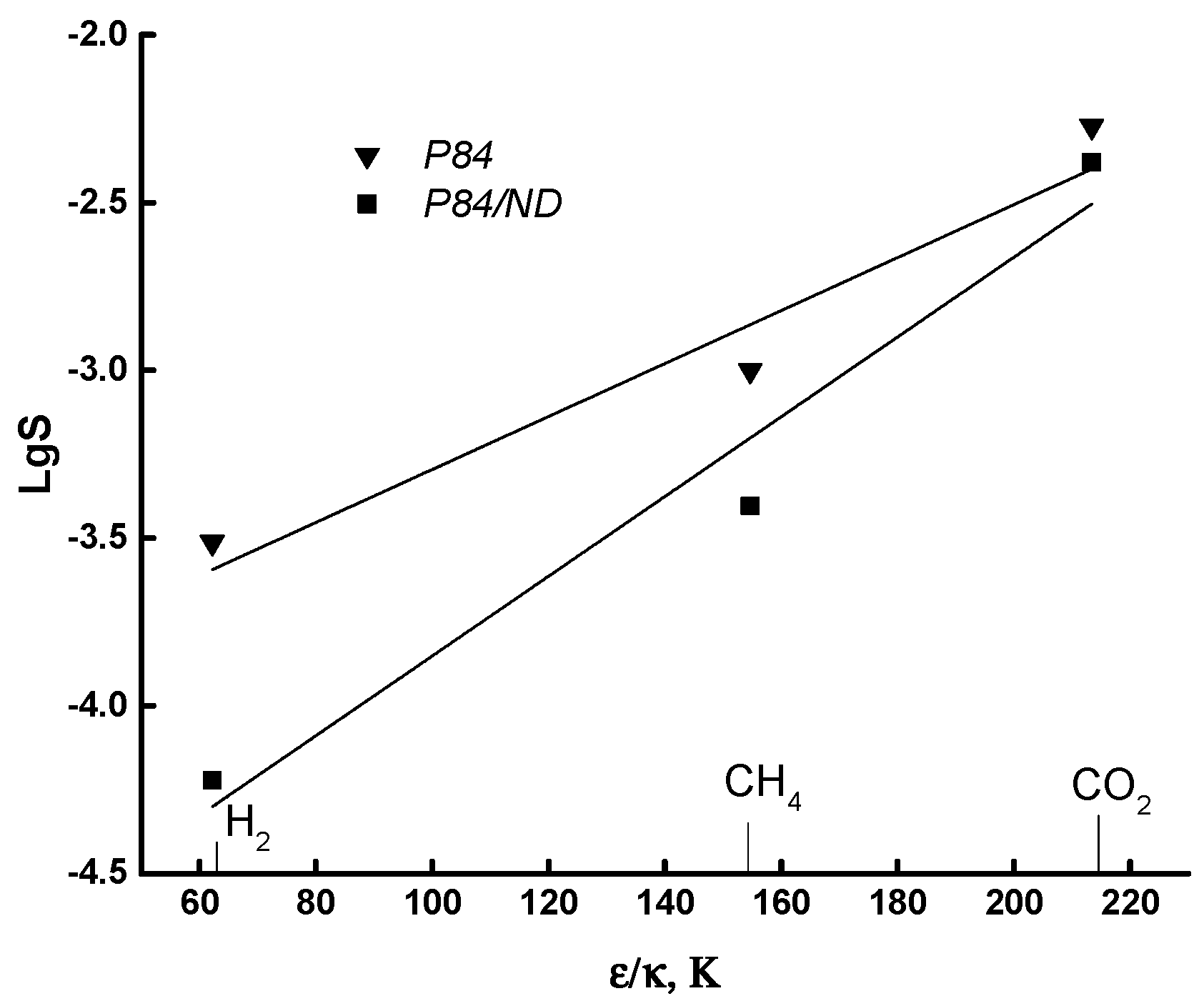

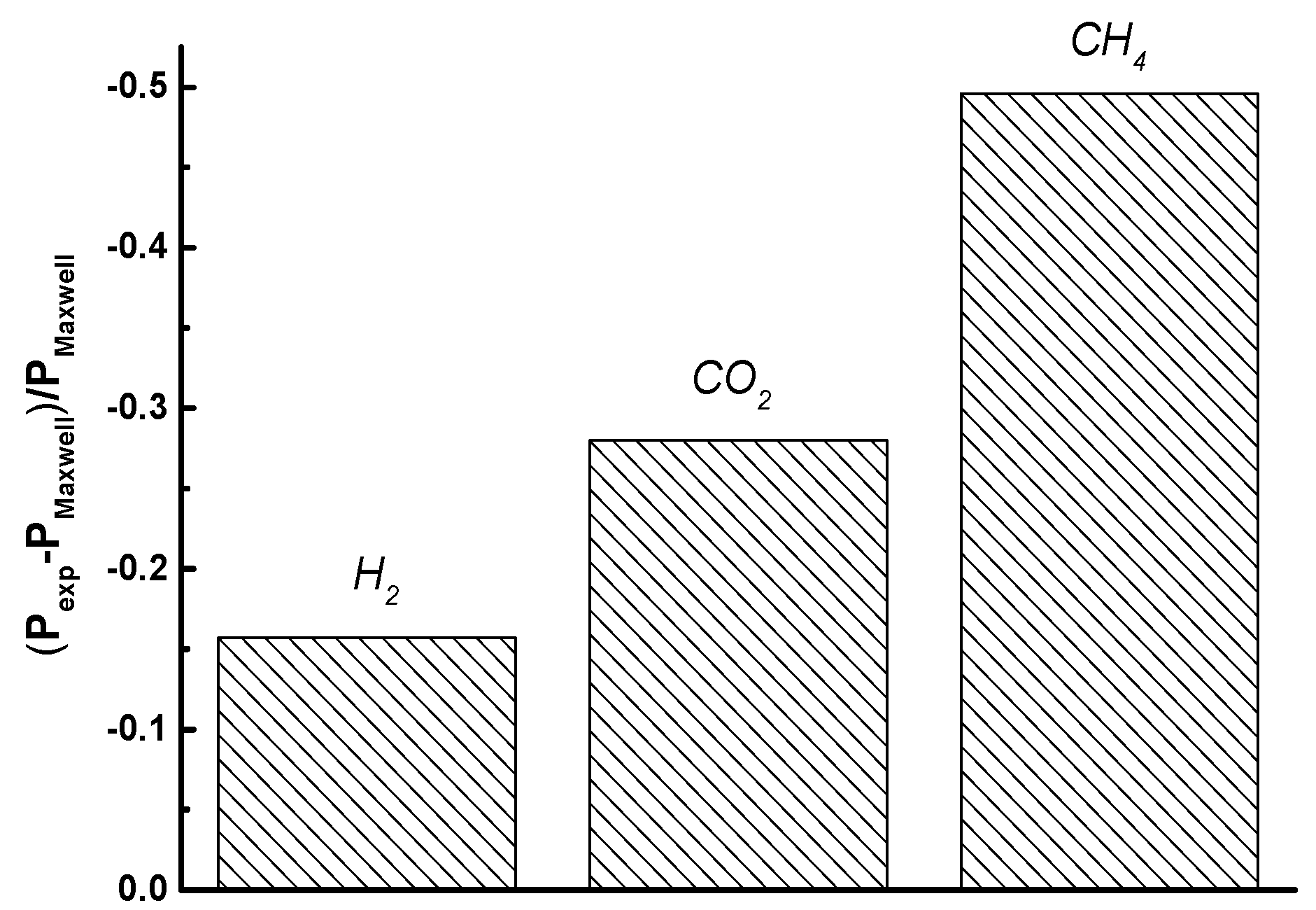

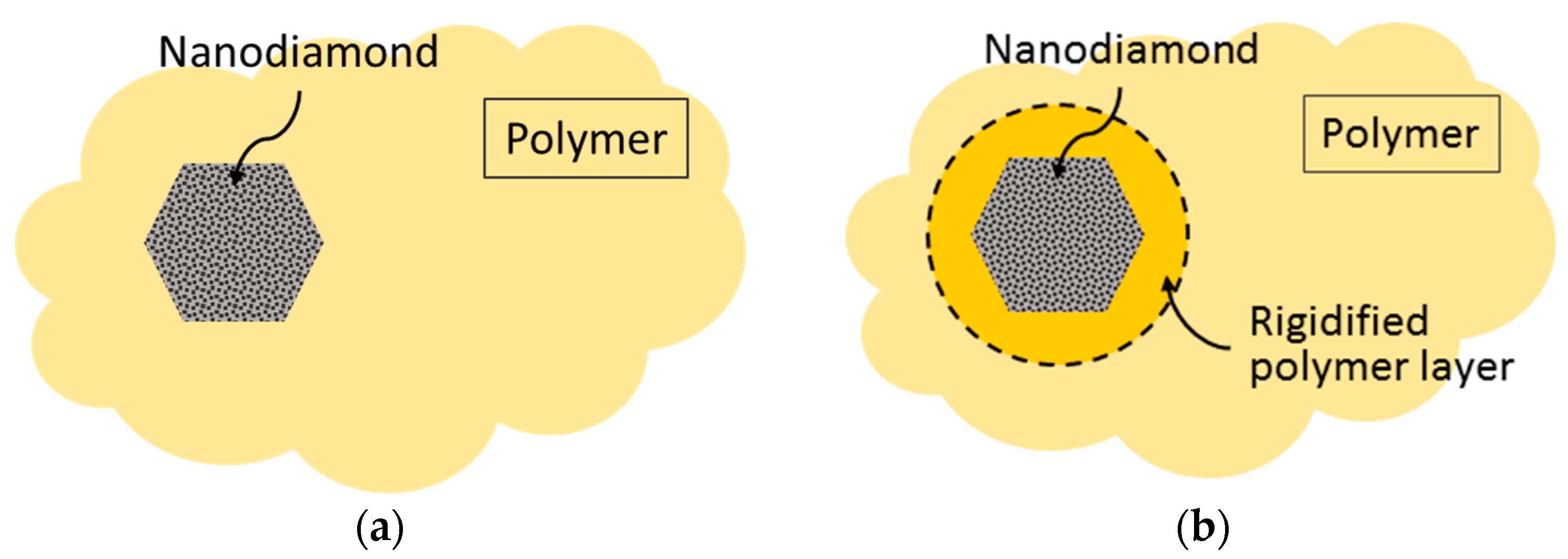

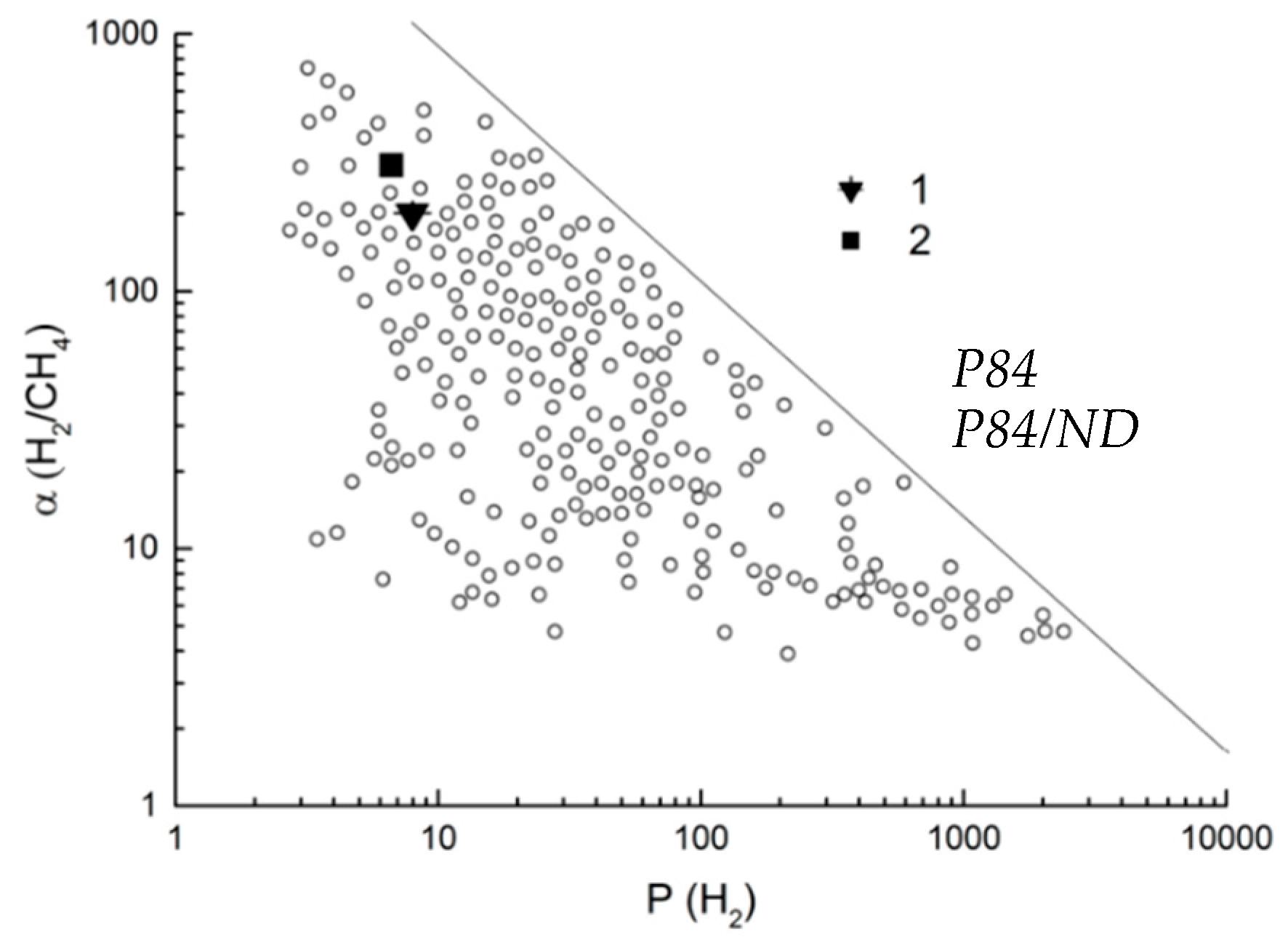

3.3. Transport Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yampolskii, Y.; Pinnau, I.; Freeman, B.D. (Eds.) Materials Science of Membranes for Gas and Vapor Separation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 047085345X. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.W.; Low, B.T. Gas separation membrane materials: A perspective. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 6999–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbán, G.; Valdés-Solís, T. Towards the hydrogen economy? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2007, 32, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muradov, N. Hydrogen via methane decomposition: An application for decarbonization of fossil fuels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2001, 26, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A. Sustainable hydrogen production. Science 2004, 305, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-I.; Choi, D.-Y.; Jang, S.-C.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, D.-K. Hydrogen separation by multi-bed pressure swing adsorption of synthesis gas. Adsorption 2008, 14, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, A.B.; Porter, K.E. A Comparison of Membrane Separation and Distillation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2000, 78, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Low, B.T.; Chung, T.-S.; Greenberg, A.R. Polymeric membranes for the hydrogen economy: Contemporary approaches and prospects for the future. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 327, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W. Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780470743720. [Google Scholar]

- Ohya, H.; Kudryavtsev, V.V.; Semenova Svetlana, I. Polyimide Membranes. Applications, Fabrications and Properties; Kodansha Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Polotskaya, G.; Goikhman, M.; Podeshvo, I.; Kudryavtsev, V.; Pientka, Z.; Brozova, L.; Bleha, M. Gas transport properties of polybenzoxazinoneimides and their prepolymers. Polymer (Guildf) 2005, 46, 3730–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polotskaya, G.; Guliy, N.; Goikhman, M.; Podeshvo, I.; Brozova, L.; Pientka, Z. Structure and gas transport properties of polybenzoxazinoneimides with biquinoline units in the backbone. Macromol. Symp. 2015, 348, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezac, M.E.; Schöberl, B. Transport and thermal properties of poly(ether imide)/acetylene-terminated monomer blends. J. Membr. Sci. 1999, 156, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, P.; Cao, B. Effects of the side groups of the spirobichroman-based diamines on the chain packing and gas separation properties of the polyimides. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 530, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.S.; Teoh, M.M.; Chung, T.S. Hydrogen separation and purification in membranes of miscible polymer blends with interpenetration networks. Polymer (Guildf) 2008, 49, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Chung, T.-S.; Goh, S.H.; Pramoda, K.P. The effects of 1,3-cyclohexanebis(methylamine) modification on gas transport and plasticization resistance of polyimide membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 267, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Liu, L.; Cheng, S.-X.; Huang, Y.-D.; Ma, J. Comparison of diamino cross-linking in different polyimide solutions and membranes by precipitation observation and gas transport. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 312, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, P.S.; Chung, T.S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, S.L.; Pramoda, K.P. Effects of cross-linking modification on gas separation performance of Matrimid membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 225, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, B.T.; Xiao, Y.; Chung, T.S.; Liu, Y. Simultaneous occurrence of chemical grafting, cross-linking, and etching on the surface of polyimide membranes and their impact on H2/CO2 separation. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, C.M.; Ozcam, A.E.; Majikes, J.M.; Seyam, M.A.; Spontak, R.J. Extended chemical crosslinking of a thermoplastic polyimide: Macroscopic and microscopic property development. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2008, 29, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chung, T.-S.; Huang, Z.; Kulprathipanja, S. Dual-layer polyethersulfone (PES)/BTDA-TDI/MDI co-polyimide (P84) hollow fiber membranes with a submicron PES–zeolite beta mixed matrix dense-selective layer for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 277, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.Q.; Koros, W.J.; Miller, S.J. Mixed matrix membranes using carbon molecular sieves. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 211, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Pechar, T.W.; Marand, E. Poly(imide siloxane) and carbon nanotube mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. Desalination 2006, 192, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, R.; Ligi, S.; Christian, M.; Morandi, V.; Giacinti Baschetti, M.; De Angelis, M. Permeability and selectivity of ppo/graphene composites as mixed matrix membranes for CO2 capture and gas separation. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, F.; Georgopanos, P.; Shishatskiy, S.; Filiz, V.; Brinkmann, T.; Abetz, V. Development and characterization of defect-free matrimid® mixed-matrix membranes containing activated carbon particles for gas separation. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, G.; Wang, S.; Yu, S.; Pan, F.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Z. Recent advances in the fabrication of advanced composite membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Cornelius, C.J. Polyimide-SiO2-TiO2 nanocomposite structural study probing free volume, physical properties, and gas transport. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 542, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, M.; Horiuchi, H.; Yamada, Y. Synthesis and gas transport properties of hyperbranched polyimide-silica hybrid/composite membranes. Polymers (Basel) 2013, 5, 1362–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilenko, V.V. On the history of the discovery of nanodiamond synthesis. Phys. Solid State 2004, 46, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmatov, V.Y. Detonation-synthesis nanodiamonds: Synthesis, structure, properties and applications. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2007, 76, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, M.; Roy, S.; Mitra, S. Nanodiamond immobilized membranes for enhanced desalination via membrane distillation. Desalination 2014, 341, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avagimova, N.V.; Toikka, A.M.; Polotskaya, G.A. Nanodiamond-modified polyamide evaporation membranes for separating methanol-methyl acetate mixtures. Pet. Chem. 2015, 55, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avagimova, N.; Polotskaya, G.; Toikka, A.; Pulyalina, A.; Morávková, Z.; Trchová, M.; Pientka, Z. Effect of nanodiamonds additives on structure and gas transport properties of poly(phenylene-iso-phtalamide) matrix. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polotskaya, G.A.; Avagimova, N.V.; Toikka, A.M.; Tsvetkov, N.V.; Lezov, A.A.; Strelina, I.A.; Gofman, I.V.; Pientka, Z. Optical, mechanical, and transport studies of nanodiamonds/poly(phenylene oxide) composites. Polym. Compos. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerlage, M.A.M. Polyimide Ultrafiltration Membranes for Non-Aqueous Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherland, 6 May 1994. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.S. Transport properties of a polyimide solvent resistant nanofiltration membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 205, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsema, J.N.; Kapantaidakis, G.C.; van der Vegt, N.F.A.; Koops, G.H.; Wessling, M. Preparation and characterization of highly selective dense and hollow fiber asymmetric membranes based on BTDA-TDI/MDI co-polyimide. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 216, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Qiao, X.; Chung, T.-S. The development of high performance P84 co-polyimide hollow fibers for pervaporation dehydration of isopropanol. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 6674–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.F. Physical properties of molecular crystals, liquids and glasses. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-1 Polym. Chem. 1969, 7, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Weber, S.G. Morphology and free volume of nanocomposite Teflon AF 2400 films and their relationship to transport behavior. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 443, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pientka, Z.; Brozova, L.; Pulyalina, A.Y.; Goikhman, M.Y.; Podeshvo, I.V.; Gofman, I.V.; Saprykina, N.N.; Polotskaya, G.A. Synthesis and characterization of polybenzoxazinone and its prepolymer using gas separation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214, 2867–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malykh, O.V.; Golub, A.Y.; Teplyakov, V.V. Polymeric membrane materials: New aspects of empirical approaches to prediction of gas permeability parameters in relation to permanent gases, linear lower hydrocarbons and some toxic gases. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 164, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, T.C.; Freeman, B.D.; Spontak, R.J.; He, Z.; Pinnau, I.; Meakin, P.; Hill, A.J. Sorption, Transport, and structural evidence for enhanced free volume in poly(4-methyl-2-pentyne)/fumed silica nanocomposite membranes. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, R.K. Modeling the barrier properties of polymer-layered silicate nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 9189–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aris, R. On a problem in hindered diffusion. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1986, 95, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeham, W.A.; Mason, E.A. diffusion through multiperforate laminae. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1979, 18, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minelli, M.; Baschetti, M.G.; Doghieri, F. Analysis of modeling results for barrier properties in ordered nanocomposite systems. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 327, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.T.; Koros, W.J. Non-ideal effects in organic-inorganic materials for gas separation membranes. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 739, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.T.; Mahajan, R.; Vu, D.Q.; Koros, W.J. Hybrid membrane materials comprising organic polymers with rigid dispersed phases. AIChE J. 2004, 50, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safak Boroglu, M.; Yumru, A.B. Gas separation performance of 6FDA-DAM-ZIF-11 mixed-matrix membranes for H2/CH4 and CO2/CH4 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 173, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanč, M.; Sysel, P.; Šoltys, M.; Štěpánek, F.; Fónod, K.; Klepić, M.; Vopička, O.; Lhotka, M.; Ulbrich, P.; Friess, K. Synthesis, preparation and characterization of novel hyperbranched 6FDA-TTM based polyimide membranes for effective CO2 separation: Effect of embedded mesoporous silica particles and siloxane linkages. Polymer (Guildf) 2018, 144, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Pan, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Effective enhancement of gas separation performance in mixed matrix membranes using core/shell structured multi-walled carbon nanotube/graphene oxide nanoribbons. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 065702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gas | d, nm | (ε/k), K |

|---|---|---|

| H2 | 0.210 | 62.2 |

| CO2 | 0.302 | 213.4 |

| CH4 | 0.318 | 154.7 |

| Membrane | Contact Angle of Water, ° | Density, g/cm3 | Fractional Free Volume | Tg, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P84 | 72.0 ± 0.5 | 1.323 ± 0.005 | 0.082 ± 0.01 | 344 ± 3 |

| P84/ND | 70.0 ± 0.4 | 1.343 ± 0.003 | 0.073 ± 0.01 | 346 ± 3 |

| Membrane | Permeability, Barrer | Ideal Selectivity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | CO2 | CH4 | H2/CO2 | H2/CH4 | CO2/CH4 | |

| P84 | 8.0 | 2.25 | 0.040 | 3.6 | 200 | 56 |

| P84/ND | 6.7 | 1.61 | 0.022 | 4.1 | 310 | 75 |

| Membrane | Diffusion Coefficient, D × 10−12 m/s | Solubility Coefficients, S × 10−3 mol/(m3 Pa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | CO2 | CH4 | H2 | CO2 | CH4 | |

| P84 | 44.7 | 0.18 | 0.034 | 0.31 | 5.0 | 1.0 |

| P84/ND | 7.3 | 0.10 | 0.018 | 0.06 | 4.0 | 0.4 |

| Membrane | Permeability, Barrer | Ideal Selectivity | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | CO2 | CH4 | H2/CO2 | H2/CH4 | CO2/CH4 | ||

| P84/ND | 6.7 | 1.61 | 0.022 | 4.1 | 310 | 75 | This work |

| Matrimid/ZIF-1 (10%) | 28.11 | 6.75 | 0.29 | 4 | 97 | 23 | [51] |

| 6FDA-TTM/Si-H (5%) | 62.6 | 29.7 | 0.39 | 2.1 | 160.5 | 76 | [52] |

| PI/MWCNT@GONRs (2%) | 42.5 | 25.2 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 18.5 | 11 | [53] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pulyalina, A.; Polotskaya, G.; Rostovtseva, V.; Pientka, Z.; Toikka, A. Improved Hydrogen Separation Using Hybrid Membrane Composed of Nanodiamonds and P84 Copolyimide. Polymers 2018, 10, 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10080828

Pulyalina A, Polotskaya G, Rostovtseva V, Pientka Z, Toikka A. Improved Hydrogen Separation Using Hybrid Membrane Composed of Nanodiamonds and P84 Copolyimide. Polymers. 2018; 10(8):828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10080828

Chicago/Turabian StylePulyalina, Alexandra, Galina Polotskaya, Valeriia Rostovtseva, Zbynek Pientka, and Alexander Toikka. 2018. "Improved Hydrogen Separation Using Hybrid Membrane Composed of Nanodiamonds and P84 Copolyimide" Polymers 10, no. 8: 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10080828

APA StylePulyalina, A., Polotskaya, G., Rostovtseva, V., Pientka, Z., & Toikka, A. (2018). Improved Hydrogen Separation Using Hybrid Membrane Composed of Nanodiamonds and P84 Copolyimide. Polymers, 10(8), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10080828