The Modulated Hot Spot Formation of Void Defects During Laser Initiation in RDX Energetic Crystals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Models and Simulation Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single Void Defect

3.1.1. Effects of Void Defect Size

3.1.2. Effects of Front and Rear Void Defect

3.2. Multiple Void Defects

3.2.1. Effects of Separation Distance

3.2.2. Effects of the Number of Void Defects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhong, K.; Bu, R.P.; Jiao, F.B.; Liu, G.R.; Zhang, C.Y. Toward the defect engineering of energetic materials: A review of the effect of crystal defects on the sensitivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Gao, H.; Zhao, F.; Ma, H. Progress on the application of graphene-based composites toward energetic materials: A review. Def. Technol. 2024, 31, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, D.; Ou, Y.; Du, S.; Jiao, Q.; Peng, J.; Liu, P. Recent Advances in Polydopamine for Surface Modification and Enhancement of Energetic Materials: A Mini-Review. Crystals 2023, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, F.P.; Yoffe, A.D. Fast Reactions in Solids; Butterworths Scientific Publications: London, UK, 1958; pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B.W.; Kroonblawd, M.P.; Strachan, A. The Potential Energy Hotspot: Effects of Impact Velocity, Defect Geometry, and Crystallographic Orientation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 3743–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, N.K.; Sen, O.; Udaykumar, H.S. Macro-scale sensitivity through meso-scale hotspot dynamics in porous energetic materials: Comparing the shock response of 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene (TATB) and 1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazoctane (HMX). J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 085903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, W.P.; Johnson, B.P.; Dlott, D.D. Hot Spot Chemistry in Several Polymer-Bound Explosives under Nanosecond Shock Conditions. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2020, 45, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Johnson, B.P.; Zhou, X.; Nguyen, Y.T.; Dlott, D.D.; Udaykumar, H.S. Hot spot ignition and growth from tandem micro-scale simulations and experiments on plastic-bonded explosives. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 131, 205901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiki, M.; Menon, S. A model for hot spot formation in shocked energetic materials. Combust. Flame 2015, 162, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.E. Hot spot ignition mechanisms for explosives. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992, 25, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.P.; Zhou, X.; Ihara, H.; Dlott, D.D. Observing Hot Spot Formation in Individual Explosive Crystals Under Shock Compression. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 4646–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, C.; Nguyen, Y.T.; Zhao, P.; Perera, D.; Kruse, L.E.; Sewell, T.; Udaykumar, H.S. Shock-induced collapse of elongated pores: Comparison of all-atom molecular dynamics and atomistics-consistent continuum simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 137, 145901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffelt, C.; Olsen, D.; Miller, C.; Zhou, M. Effect of void positioning on the detonation sensitivity of a heterogeneous energetic material. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 131, 065101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.; Seshadri, P.; Sen, O.; Hardin, D.B.; Molek, C.D.; Udaykumar, H.S. Multi-scale modeling of shock initiation of a pressed energetic material I: The effect of void shapes on energy localization. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 131, 055906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, P.; Xia, Y. Understanding the Deformation and Fracture Behavior of β−HMX Crystal and Its Polymer−Bonded Explosives with Void Defects on the Atomic Scale. Crystals 2025, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.C.; Qin, W.Z.; Tang, D.; Ji, F.M.; Chen, H.S.; Yang, F.; Qiao, Z.Q.; Duan, T.; Lin, D.; He, R.; et al. Constructing interparticle hotspots through cracking silver nanoplates for laser initiation of explosives. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 139, 106989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Xiang, X.; Huang, M.; Liao, W.; Yang, Z.; Tan, B.; Li, Z.; et al. Scratch defects modulated hot spots generation in laser irradiated RDX crystals: A 3D FDTD simulation. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 8812–8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zhao, X.; Rui, J.; Zhao, J.; Xu, M.; Zhai, L. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Influence of RDX Internal Defects on Sensitivity. Crystals 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.T.; Okafor, C.; Zhao, P.; Sen, O.; Picu, C.R.; Sewell, T.; Udaykumar, H. Continuum models for meso-scale simulations of HMX (1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocane) guided by molecular dynamics: Pore collapse, shear bands, and hotspot temperature. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 114902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Walton, A.J. Optical sensitising of insensitive energetic material for laser ignition. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Yan, Y.-F.; Qian, R.-X.; Fan, B.-W.; Bian, H.-Y.; Wen, F.; Xu, J.-G.; Zheng, F.-K.; Guo, G.-C. Structure-Induced Energetic Coordination Compounds as Additives for Laser Initiation Primary Explosives. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2414886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, Y.; Chen, P.; Yao, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, R. Initial response and combustion behavior of microscale Al/PTFE energetic material by nanosecond laser ignition. Combust. Flame 2023, 254, 112838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-W.; You, S.; Suslick, K.S.; Dlott, D.D. Hot spots in energetic materials generated by infrared and ultrasound, detected by thermal imaging microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 85, 023705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-W.; You, S.; Suslick, K.S.; Dlott, D.D. Hot spot generation in energetic materials created by long-wavelength infrared radiation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 061907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K. Numerical solution of initial boundary value problems involving Maxwell’s equations in isotropic media. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1966, 14, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, F.L.; Sarris, C.; Zhang, Y.; Na, D.Y.; Berenger, J.P.; Su, Y.; Okoniewski, M.; Chew, W.C.; Backman, V.; Simpson, J.J. Finite-difference time-domain methods. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, S.; Hayati, M. Optical biosensors using plasmonic and photonic crystal band-gap structures for the detection of basal cell cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, N.; Motiei, M.; Dar, N.; Ankri, R. Cyanine-Conjugated Gold Nanospheres for Near-Infrared Fluorescence-Based Biomedical Imaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 10104–10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronnemose, W.; Rabus, B.T. 3-D FDTD Framework for Simulating SAR Imagery of Realistic Near Earth Surface Volumes (Soil, Snow, and Vegetation). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 2004211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.; Gasdia, F.; Simpson, J.J.; Marshall, R.A. 3-D FDTD Modeling of Long-Distance VLF Propagation in the Earth-Ionosphere Waveguide. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 69, 7743–7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Cui, W.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Lu, S.; Huo, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; et al. Ultra-broadband and wide-angle solar absorber for the All-MXene grating metamaterial. Opt. Mater. 2024, 149, 115073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, A.T.; Vișan, A.I.; Popescu-Pelin, G.F. Design and Processing of Metamaterials. Crystals 2025, 15, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, D.-Y.; Chew, W.C. Quantum Electromagnetic Finite-Difference Time-Domain Solver. Quantum Rep. 2020, 2, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Khordad, R.; Jalali, T. Q-BOR–FDTD method for solving Schrödinger equation for rotationally symmetric nanostructures with hydrogenic impurity. Phys. Scr. 2022, 97, 025802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Venuthurumilli, P.K.; Xu, X. Inverse Design of Plasmonic Structures with FDTD. ACS Photonics 2021, 8, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyubin, A.Y.; Kon, I.I.; Poltorabatko, D.A.; Samusev, I.G. FDTD Simulations for Rhodium and Platinum Nanoparticles for UV Plasmonics. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhu, G.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. FDTD simulation of the optical properties for gold nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 125009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyubin, A.; Kon, I.; Tcibulnikova, A.; Matveeva, K.; Khankaev, A.; Myslitskaya, N.; Lipnevich, L.; Demishkevich, E.; Medvedskaya, P.; Samusev, I.; et al. Numerical FDTD-based simulations and Raman experiments of femtosecond LIPSS. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 4547–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

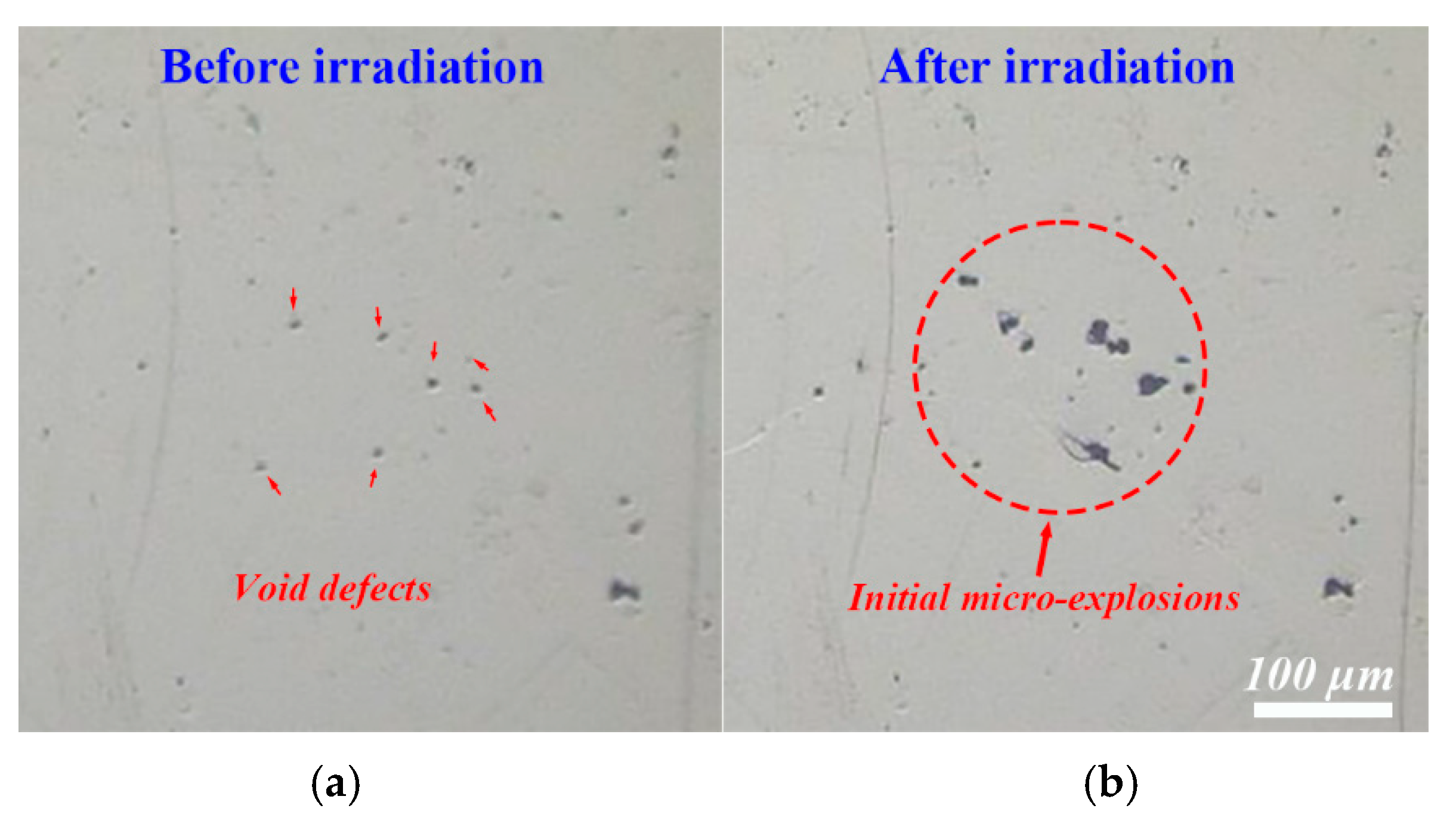

- Yan, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiang, X.; Huang, M.; Tan, B.; Zhou, G.; et al. Quantitative correlation between facets defects of RDX crystals and their laser sensitivity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 313, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, G.; Yang, L.; Xiang, X.; Li, X.; et al. Laser initiation of RDX crystal slice under ultraviolet and near-infrared irradiations. Combust. Flame 2018, 190, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, K.; Chhabra, J.S. Static charge development and impact sensitivity of high explosives. J. Hazard. Mater. 1993, 34, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenger, J.P. A perfectly matched layer for the absorption of electromagnetic waves. J. Comput. Phys. 1994, 114, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, W.; Pan, N.; Chen, X.; Xiang, X.; Zu, X.; Tan, B.; et al. The Modulated Hot Spot Formation of Void Defects During Laser Initiation in RDX Energetic Crystals. Crystals 2026, 16, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010027

Yan Z, Yang J, Zhang S, Zheng J, Li W, Pan N, Chen X, Xiang X, Zu X, Tan B, et al. The Modulated Hot Spot Formation of Void Defects During Laser Initiation in RDX Energetic Crystals. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zhonghua, Jiaojun Yang, Shuhuai Zhang, Jiangen Zheng, Weiping Li, Nana Pan, Xiang Chen, Xia Xiang, Xiaotao Zu, Bisheng Tan, and et al. 2026. "The Modulated Hot Spot Formation of Void Defects During Laser Initiation in RDX Energetic Crystals" Crystals 16, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010027

APA StyleYan, Z., Yang, J., Zhang, S., Zheng, J., Li, W., Pan, N., Chen, X., Xiang, X., Zu, X., Tan, B., Yuan, X., & Fang, R. (2026). The Modulated Hot Spot Formation of Void Defects During Laser Initiation in RDX Energetic Crystals. Crystals, 16(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010027