1. Introduction

The alkoxycyanobiphenyls (

CBOn, M series) and alkylcyanobiphenyls (

CBn, K series), discovered by Gray and coworkers, are very well-known compounds in the field of liquid crystals [

1,

2]. Amongst them, 4-cyano-4′-pentylbiphenyl (

5CB) is probably the most prized due to its stable nematic mesophase at ambient temperature. Since their discovery, there has been persistent research on the structure modification of these alkoxycyanobiphenyl and alkylcyanobiphenyl mesogens with the objective of better understanding the structure–property relationships and ultimately of discovering compounds with improved mesogenic properties.

There has been significant research into modifying the structure and properties of alkoxycyanobiphenyls by additional functionalization, such as the replacement of hydrogen atoms on the aromatic core [

3,

4]. In addition to core modifications of alkoxycyanobiphenyls, compounds with modifications in the tail are also reported in the literature. For example, alkoxycyanobiphenyls with a perfluorinated tail have been reported [

5]. Alkoxycyanobiphenyls with a hydroxy (OH) group [

6], a thiol group (SH) [

7], a cyano (CN) group [

8], and halogens like Cl, Br, or F [

9,

10] at the terminal position of the tail have been synthesized, and their phase behavior has been studied. Moreover, a series of alkoxycyanobiphenyls with a pentafluorophenoxy group were synthesized to study the influence of the presence of a larger terminus on the phase behavior of alkoxycyanobiphenyls [

11]. When alkoxycyanobiphenyls are modified by adding various substituents to the tail, it is common to locate the substituent at the tail’s terminal location. This is because of the accessibility of starting materials and the viability of the relevant synthetic processes.

The introduction of fluorine into the structure of liquid crystals has been a common and effective practice to modify their phase behavior [

3,

4,

9,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. As mentioned earlier, alkoxycyanobiphenyls with fluorine at the terminal position of the tail have been synthesized, and their phase behavior has been studied. Interesting effects, including the depression of phase transition temperatures and depression of the formation of a smectic mesophase, were observed compared to the phase behavior of the nonfluorinated analogs [

9].

Motivated by the useful impact of monofluorine tail termination on the phase behavior of the alkoxycyanobiphenyls and alkylcyanobiphenyls [

9], additional alkoxycyanobiphenyls and alkylcyanobiphenyls with a single fluorine atom at various other possible positions of the tail were synthesized. Their phase behavior was examined in our lab, and the results have been published [

12,

19]. In those projects [

12,

19], the final fluorinated compounds were synthesized from the corresponding hydroxy intermediates with high enantiomeric purity using 2-pyridinesulfonyl fluoride (Pyfluor) [

28] as the deoxyfluorination agent.

In the present study, the tail of the alkoxycyanobiphenyls (CBOn) is modified by the incorporation of two adjacent fluorine atoms, one on each of two terminal carbon atoms—CBOndF(n-1,n)—to learn about the influence of the incorporation of two fluorine atoms on the phase behavior versus one fluorine atom in the tail of alkoxycyanobiphenyls. The abbreviation CBOn means alkoxycyanobiphenyl with n number of carbons in the tail, whereas the abbreviation CBOndF(n-1,n) means an alkoxycyanobiphenyl with n number of carbons in the tail, with fluorination occurring at both the n-1 and n positions.

The scope is restricted to the synthesis and phase behavior analysis of the racemate and pure enantiomers of 4′-(2,3-difluoropropoxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile CBO3dF(2,3) and 4′-(4,5-difluoropentyloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile CBO5dF(4,5). In this article, the phase behavior of the racemate and pure enantiomers of the produced tail-terminated difluorinated alkoxycyanobiphenyls (CBOndF(n-1,n) is examined and compared. The phase behavior of nonfluorinated and monofluorinated tail-terminated analogs of alkoxycyanobiphenyls is also compared to the phase behavior of the produced tail-terminated difluorinated alkoxycyanobiphenyls (CBOndF(n-1,n). Moreover, in this project, serendipitously, a sample of enantiomerically impure CBO5dF(4,5) was synthesized, and hence the phase behavior of the enantiomerically impure sample of CBO5dF(4,5) was compared to the enantiomerically pure sample of CBO5dF(4,5). The phase behavior of the enantiomerically impure and enantiomerically pure intermediates involved in CBO5dF(4,5) synthesis was also compared. In addition, many of the hydroxylated synthetic intermediates were found to be mesogenic, and their phase behavior has also been evaluated and presented in this article.

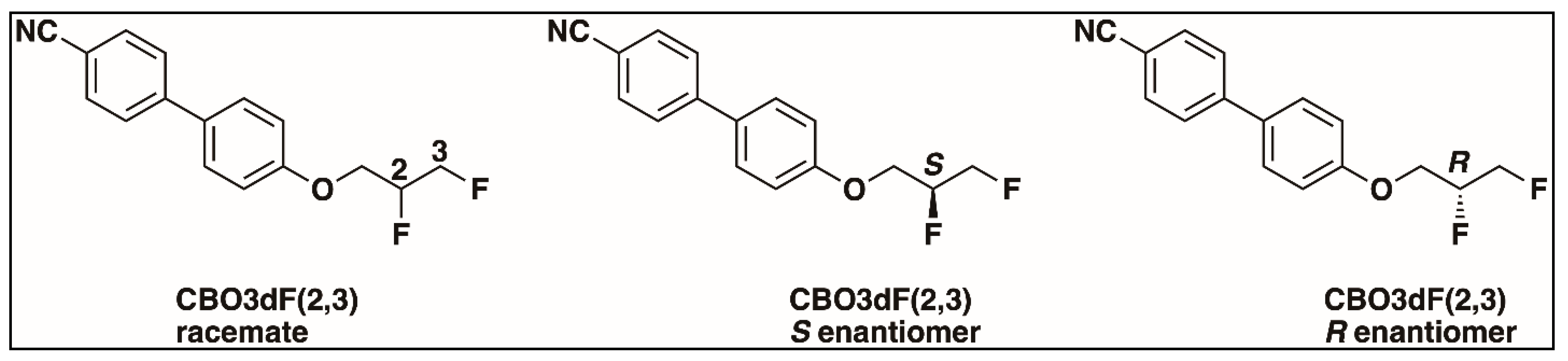

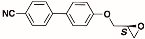

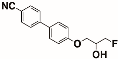

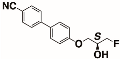

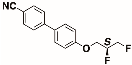

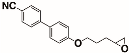

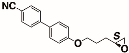

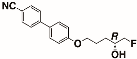

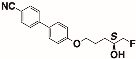

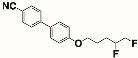

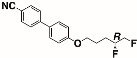

The structures of the racemate and both enantiomers of 4′-(2,3-difluoropropoxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile

CBO3dF(2,3) are shown in

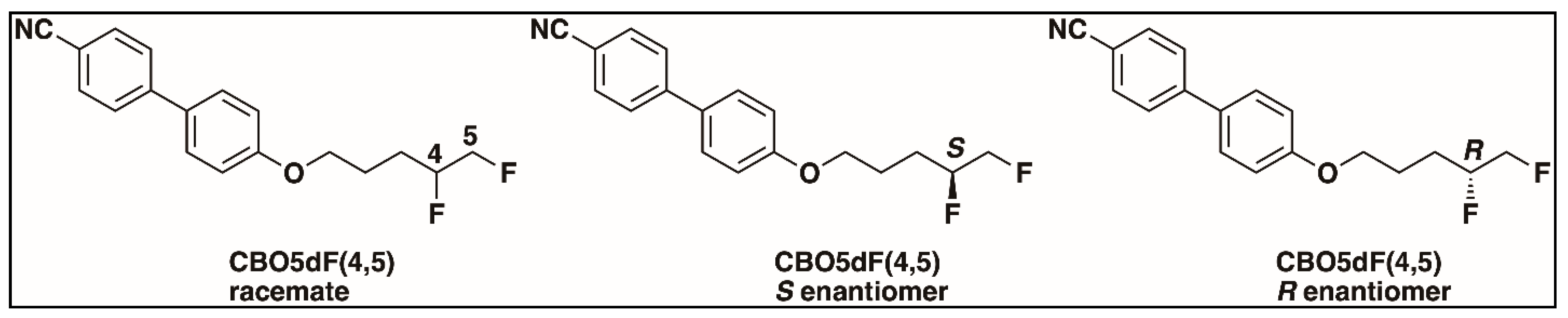

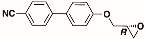

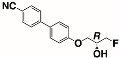

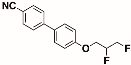

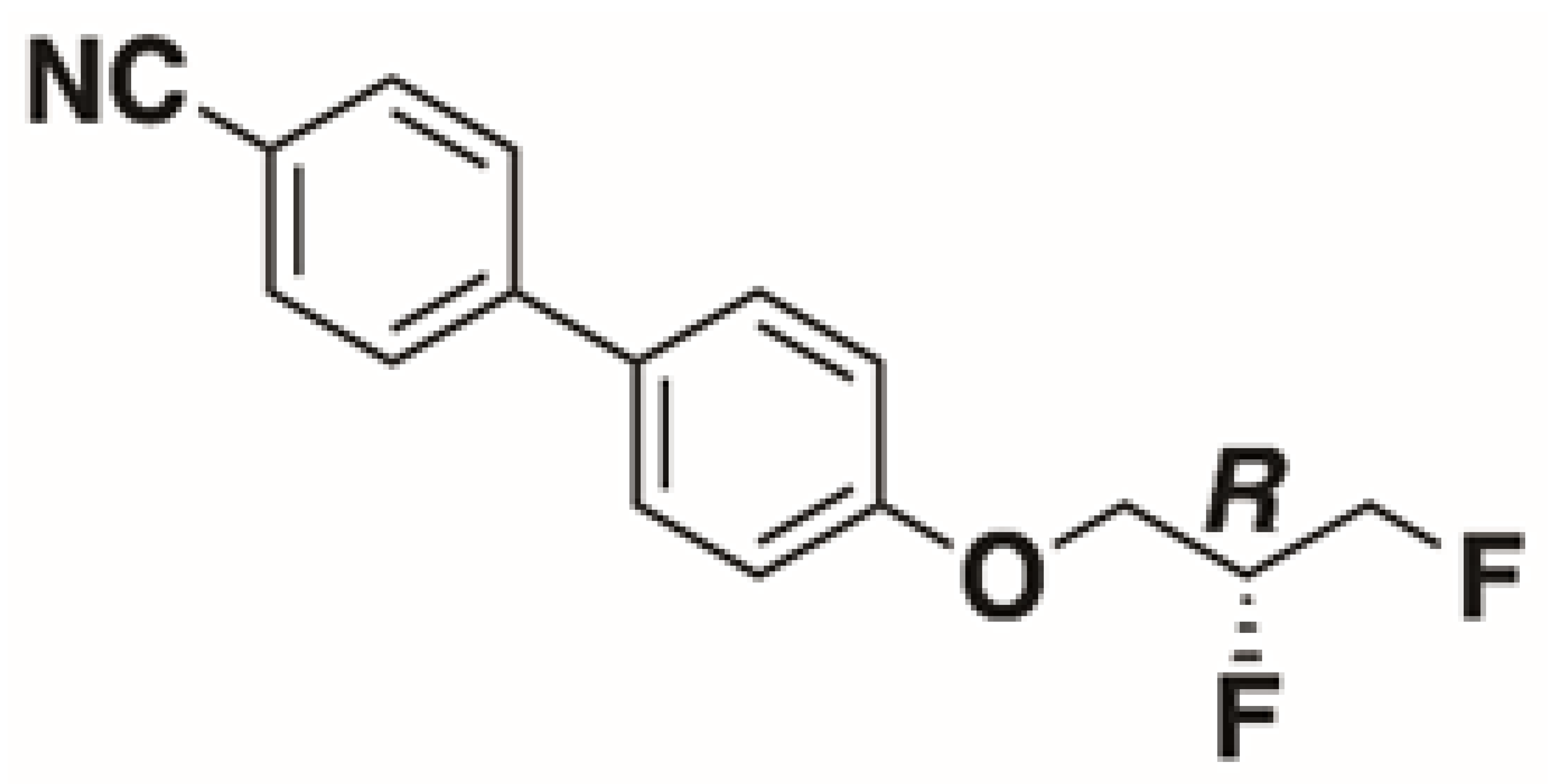

Figure 1. The structures of the racemate and the enantiomers of 4′-(4,5-difluoropentyloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile

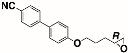

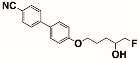

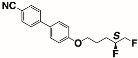

CBO5dF(4,5) are shown in

Figure 2.

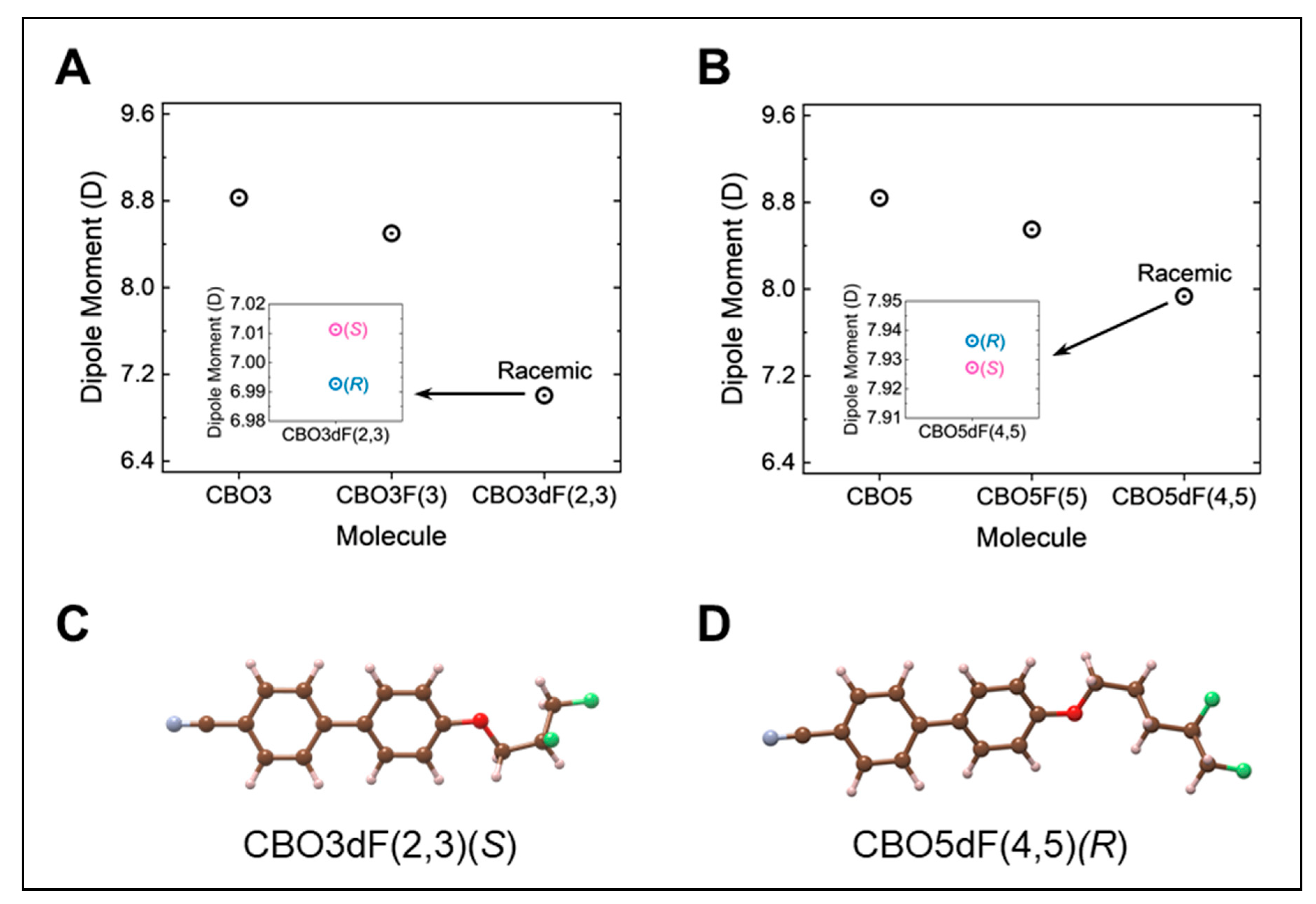

Additionally, the dipole moments of the CBOndF(n-1,n) compounds were calculated with quantum chemical methods to subsequently elucidate any correlation between dipole moments and the phase behavior of the compounds, and to further understand the influence of dipole moments after the introduction of two fluorine atoms in the tail of alkoxycyanobiphenyls.

2. Materials and Methods

The compounds were synthesized via regioselective opening of the racemic and chiral epoxy intermediate by fluoride nucleophile, followed by deoxyfluorination. The racemic and chiral epoxy intermediates were synthesized by Mitsunobu reaction, alkylation, followed by epoxidation and hydrolytic kinetic resolution reactions. All precursors, reagents, and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. The chiral precursors (R)-glycidol and (S)-glycidol were purchased from Combi-blocks (San Diego, CA, USA).

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) was performed using silica gel plates (Scientific Adsorbents, Atlanta, GA, USA). The products were purified by column chromatography using a silica gel (60–120 mesh) and/or by recrystallization using ACS-grade solvents.

A Bruker 400 NMR (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) and Agilent 500 NMR (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used for NMR data acquisition (Frequency: 400 MHz and 500 MHz for 1H-NMR; 101 MHz and 126 MHz for 13C-NMR and 470 MHz for 19F-NMR), and the plots were generated by MestreNova 14.1.1-24571 software.

A Bruker Vector 33 FT-IR instrument (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to obtain the IR spectra of the compounds. The IR data was processed with OPUS 6.5 software.

A Thermo Finnigan Trace—GC 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Austin, TX, USA) and Polaris Q Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Austin, TX, USA) were used to follow the reactions and assay product purity. The GC-MS data were collected and processed via Xcalibur software (Ver. 1.4, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA).

The enantiomeric purity of the intermediates and target compounds was evaluated using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II Quaternary HPLC instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with chiral columns including the following: Chiralcel OD-H 14325A 4.6 × 250 mm 5 µm Chiral Technologies Inc., (West Chester, PA, USA) Chiralpak AS-H 20325A 4.6 × 250 mm 5 µm Chiral Technologies Inc., Chiralpak IG-3 Part No. 87,524 4.6 mm I.D. × 150 mm, particle size, 3 µm Diacel Corporation, and Chiralpak IF-3 Part No. 86,525 4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm; particle size 3 µm Diacel Corporation. The data was processed via Agilent Infinity II software. Commercially available HPLC-grade solvents isopropyl alcohol, ethanol, and hexanes were used.

Optical rotations were obtained on a HINOTEK WZZ-2B Automatic Polarimeter (Shanghai Precision Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis was run on a 2920 Modulated DSC from TA Instruments (TA Instruments Inc., New Castle, DE, USA) to measure the phase transition behavior of the products. Experimental data were analyzed and exported by using the Thermal Advantage software (Version 1.1A, TA Instruments Inc., New Castle, DE, USA).

Polarized optical microscopy (POM) was run using a Nikon ECLIPSE E600 Microscope & SPOTTM idea COMS (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). A Mettler Toledo (Columbus, OH, USA) FP90 central processor with an FP82HT hot stage was used to observe the phase transition behavior of the products.

The dipole moments of

CBO3,

CBO3dF(2,3), and

CBO5dF(4,5) were calculated using density functional theory (DFT). DFT calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 software package at the PBE-D3(SMD=benzonitrile)/def2-SVP level of theory [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Optimized structures were subsequently evaluated through single-point calculations at the M06-2X-D3(SMD=benzonitrile)/def2-TZVP level of theory [

34]. The computational methods employed in this study were chosen for their demonstrated accuracy in modeling mesogenic properties [

35,

36,

37]. In particular, the selected approach accurately reproduces the experimental solvation free energy of 5CB [

38], a prototypical room-temperature nematic liquid crystal, with a deviation of 20 meV at 25 °C. Furthermore, the use of single-point M06-2X/def2-TZVP calculations was motivated by our prior benchmarking against the highly accurate CBS-QB3 complete basis set method [

39].

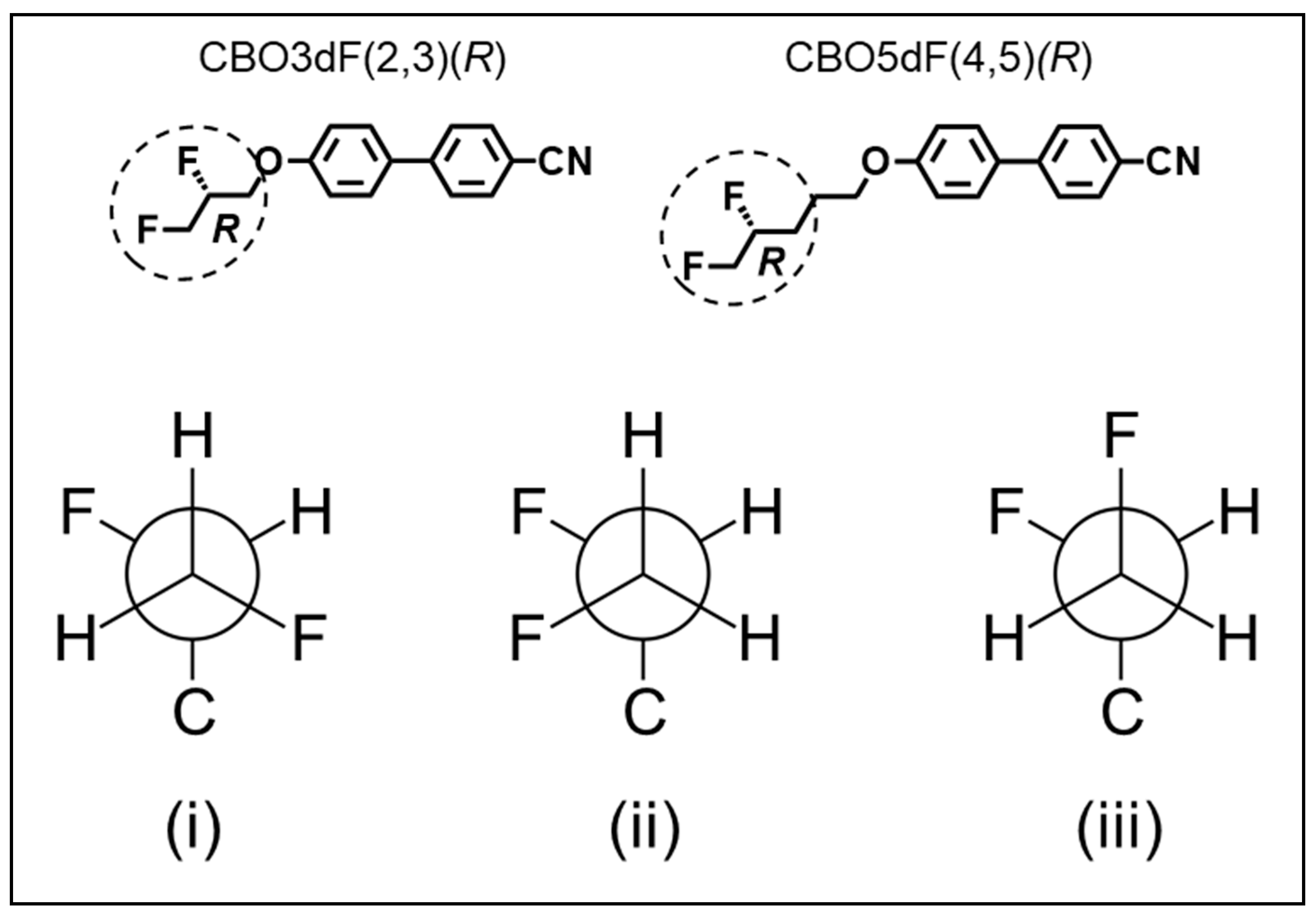

For difluorinated

CBO3dF(2,3) and

CBO5dF(4,5), both

R and

S enantiomers were considered when calculating dipole moments. Further, three staggered configurations of fluorine atoms in the difluorinated alkoxyl tail were considered (illustrated for

R enantiomers of

CBO3dF(2,3) and

CBO5dF(4,5) in

Figure 3). The initial structure of each mesogen conformer was initialized through dihedral angles of 60°, 180°, and 300° for carbon atoms in the alkoxy tail. This approach resulted in 3

m−1 configurations of dihedral angles, where

m is the number of carbon atoms in the alkoxy tail. A maximum of 1000 configurations were randomly selected for each species. Dipole moments for each compound were determined by Boltzmann-weighted averaging of the calculated dipole moments across the ensemble of sampled dihedral angles, using free-energy weights at 25 °C, as described in our prior works [

6,

8,

9,

11,

12,

18,

19].

3. Results and Discussion

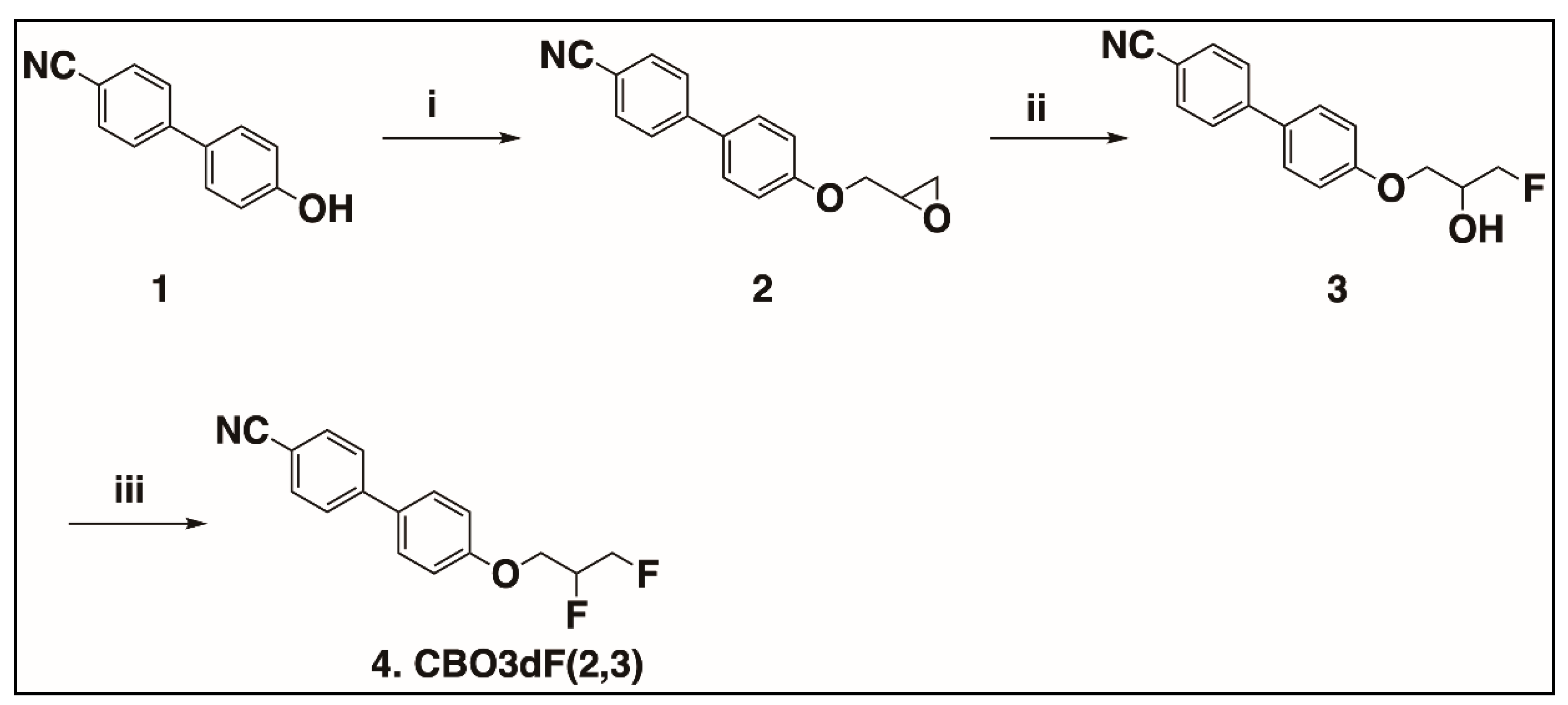

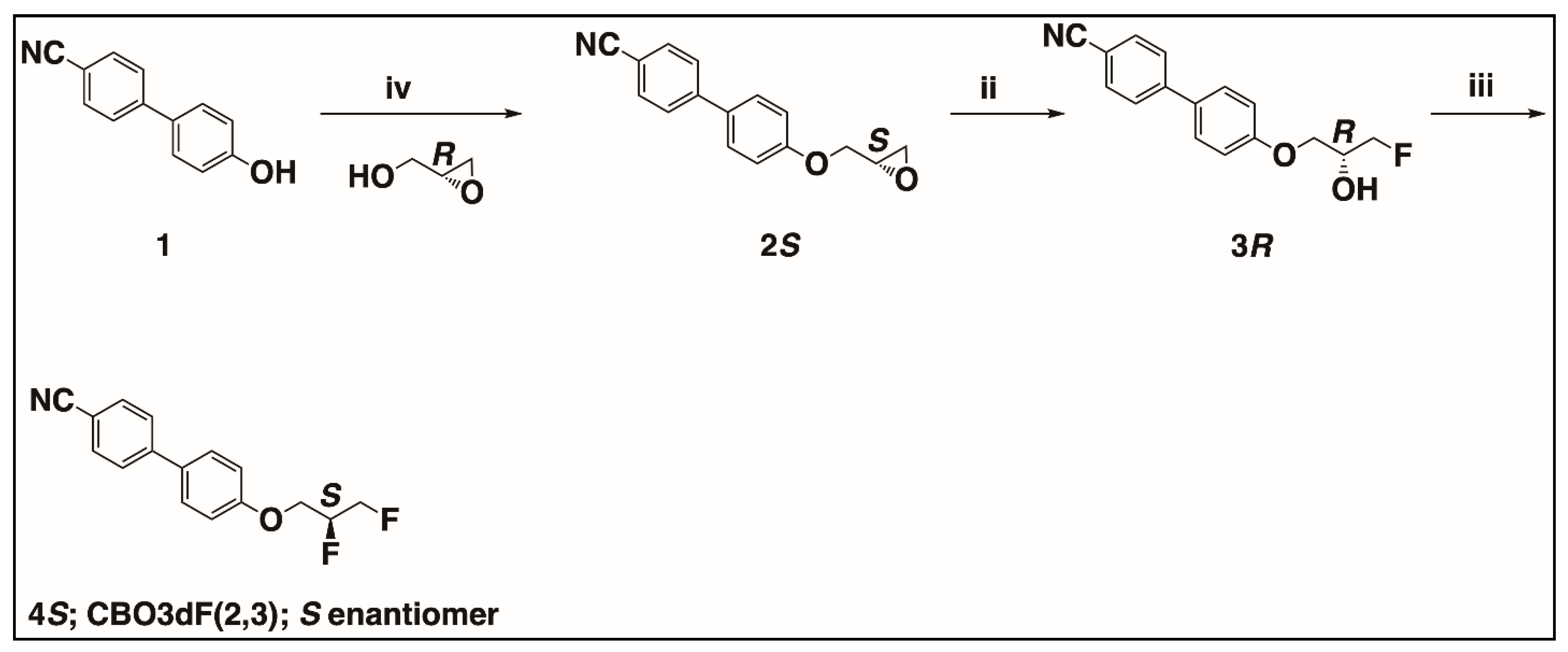

The synthesis of the compounds found in

Figure 1 is provided in

Scheme 1 and

Scheme 2. In

Scheme 1, the synthesis of racemic

CBO3dF(2,3) is shown, whereas the synthesis of the

S enantiomer of

CBO3dF(2,3) is shown in

Scheme 2.

In

Scheme 1, the first step is the alkylation of 4′-cyano-4-hydroxybiphenyl (

1) using racemic epichlorohydrin to obtain racemic 4′-(2-oxiranyl)methoxy [1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (

2). The racemic fluorohydrin intermediate 4′-(2-hydroxy-3-fluoropropoxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (

3) was synthesized by regioselective hydrofluorination of the corresponding epoxides (

2) with potassium hydrogen difluoride (KHF

2) in chlorobenzene in the presence of the catalyst tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen trifluoride (Bu

4N

+H

2F

3−) [

40]. The final target racemic compound 4′-(2,3-difluoropropoxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (

4) was synthesized from the corresponding racemic fluorohydrin intermediate (

3) using 2-pyridinesulfonyl fluoride (Pyfluor) as the deoxyfluorination reagent in the presence of base 1,8-diazabicyclo [5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) [

28].

In

Scheme 2, the first step is the synthesis of (

S)-4′-[(2-oxiranyl)methoxy][1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile

2S by reaction of 4′-cyano-4-hydroxybiphenyl (

1) with commercially available (

R)-glycidol under Mitsunobu reaction conditions. The reaction of 4′-cyano-4-hydroxybiphenyl with the primary alcohol functional group of (

R)-glycidol proceeds with the retention of configuration at the existing chiral center. The enantiomeric purity of the product

2S was found to be 99.7/0.3 er by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a chiral stationary phase. The enantiomeric purity of

2S is limited by the enantiomeric purity of the purchased (

R)-glycidol. Next,

3R was synthesized from

2S by regioselective nucleophilic ring opening of the chiral epoxy intermediate

2S with potassium hydrogen difluoride in chlorobenzene in the presence of the catalyst tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen trifluoride. The stereochemistry at the chiral center of

2S is retained in the product

3R. The enantiomeric purity of

3R was found to be 99.7/0.3 er, as determined by HPLC equipped with a chiral stationary phase, which was found to be the same as compared to the enantiomeric purity of

2S. Finally,

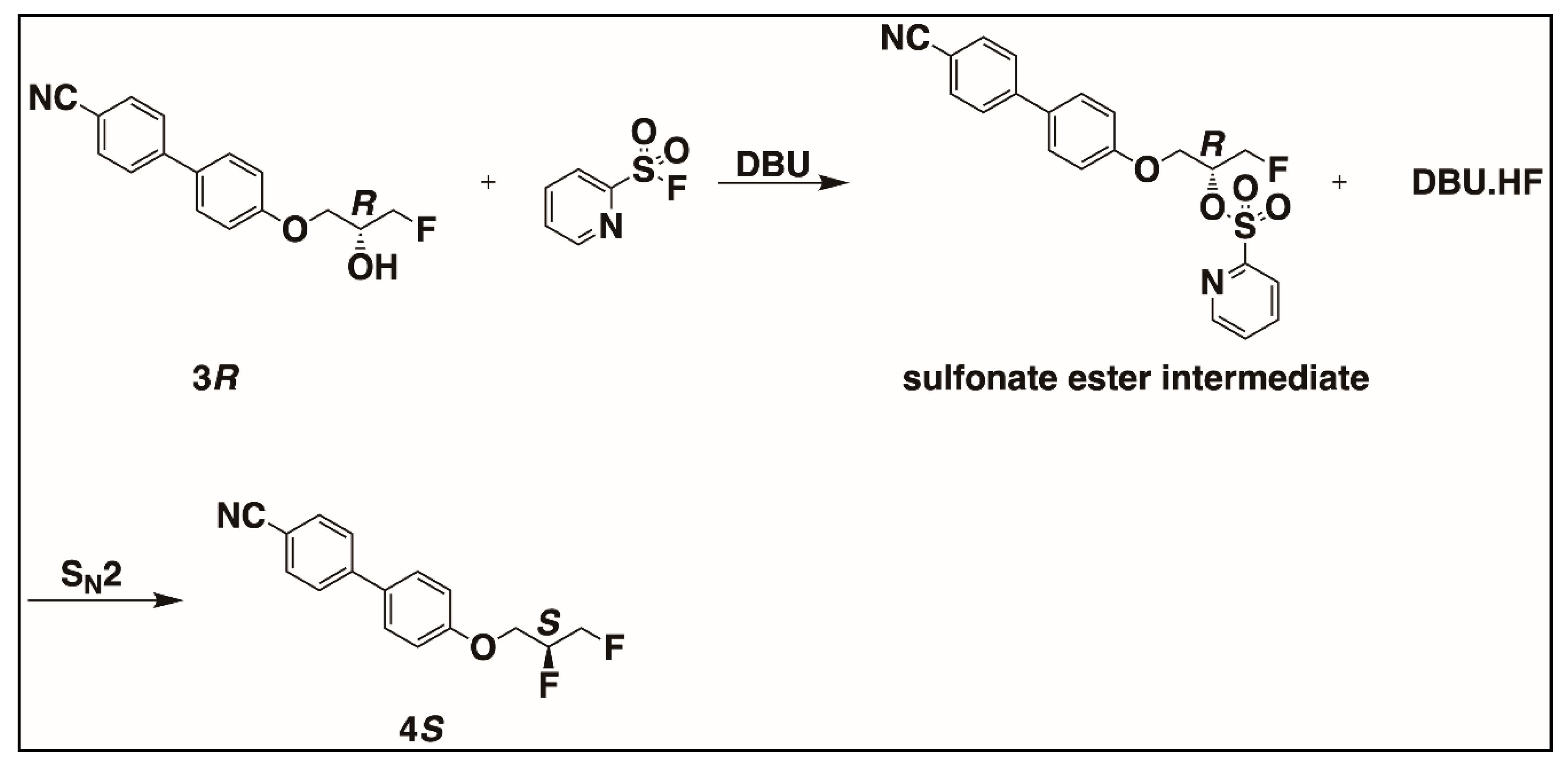

4S was synthesized from its corresponding chiral fluorohydrin intermediate

3R using Pyfluor as the deoxyfluorination reagent in the presence of base DBU. It is reported that the base DBU acts as a Brønsted base that assists in the addition of the hydroxy group of the substrate alcohol to the sulfonyl fluoride of Pyfluor to form a sulfonate ester intermediate amidine hydrogen fluoride (DBU-HF). Amidine hydrogen fluoride (DBU-HF) then mediates the fluorination of the sulfonate ester intermediate in a bimolecular nucleophilic substitution (S

N2) fashion. Hence, inversion in stereochemistry in this step is expected [

28]. The enantiomeric purity of optical antipode

4S was evaluated to be 99.3/0.7 er by HPLC equipped with a chiral stationary phase, similar to the enantiomeric purity of

3R. The complementary synthesis of the

R enantiomer of

CBO3dF(2,3) was accomplished by following all the steps for the synthesis of the

S enantiomer of

CBO3dF(2,3) as in

Scheme 2, but (

S)-glycidol was used instead of (

R)-glycidol in the first step of

Scheme 2 with the same overall enantiomeric purity 99.3/0.7 er.

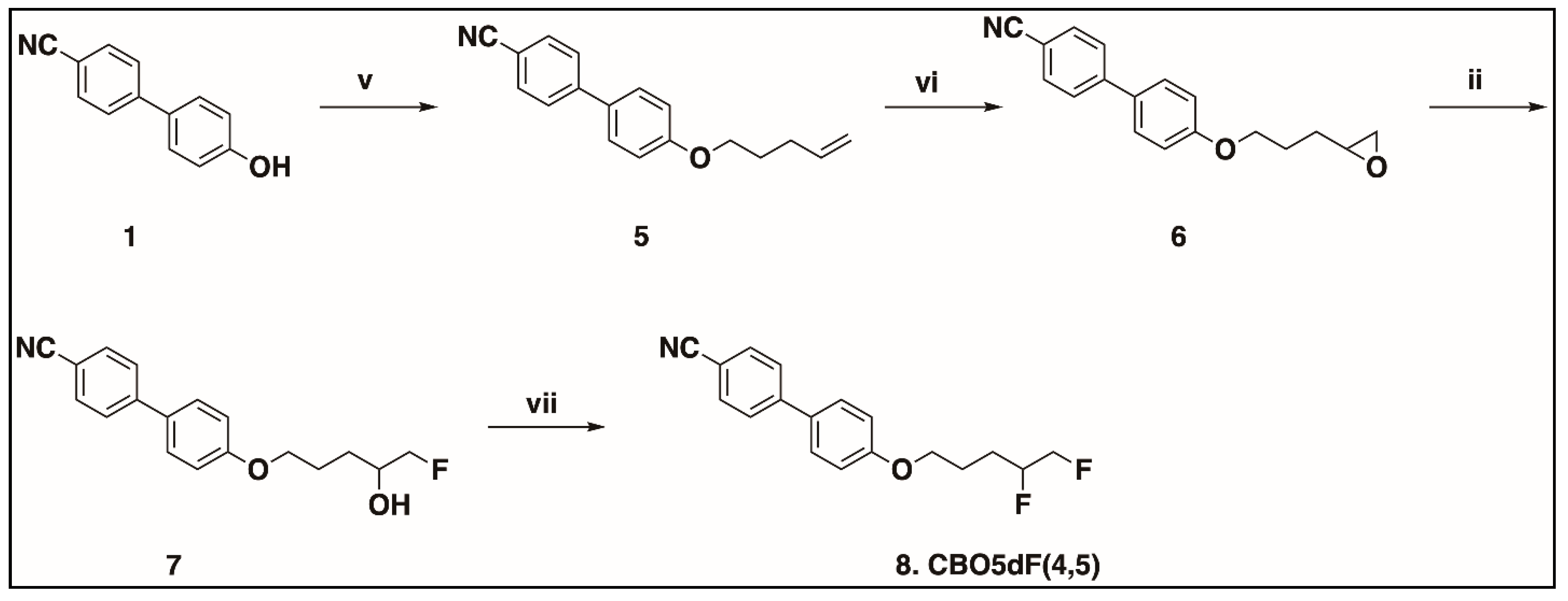

The synthesis of the compounds in

Figure 2 is shown in

Scheme 3 and

Scheme 4. In

Scheme 3, the synthesis of racemic

CBO5dF(4,5) is shown, whereas the synthesis of the

S enantiomer of

CBO5dF(4,5) is shown in

Scheme 4. In

Scheme 3, first, 4′-(4-penten-1-yloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (

5) was synthesized by alkylation of the commercially available 4′-cyano-4-hydroxybiphenyl (

1) using commercially available 5-bromopent-1-ene. Next, the epoxidation of

5 was accomplished using

m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (

mCPBA) to obtain 4′-[3-(2-oxiranyl)propoxy][1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (

6) [

41]. Then, the regioselective opening of epoxide

6 by fluoride anion using reagents potassium hydrogen difluoride in chlorobenzene in the presence of catalyst tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen trifluoride gave the fluorohydrin intermediate

7. The final step was the deoxyfluorination of the fluorohydrin intermediate

7 using Pyfluor, which provided the target racemic difluoro compound

8.

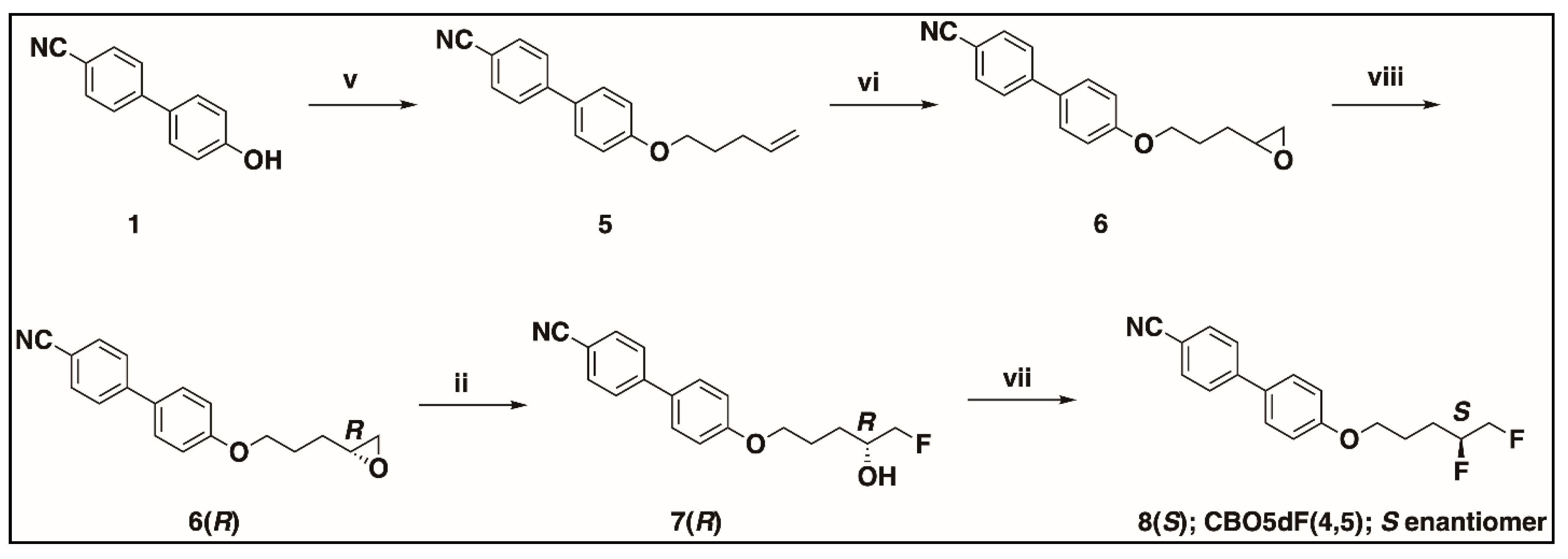

The synthesis of the

S enantiomer of

CBO5dF(4,5) is shown in

Scheme 4. Intermediate

6 was synthesized from 4′-cyano-4-hydroxybiphenyl (

1) by alkylation and epoxidation as described in

Scheme 3. Then, the chiral epoxide

6R was synthesized from the racemic epoxide

6 by a hydrolytic kinetic resolution using (

R,R)-(+)N,N’-bis(3,5-di-tert-butylsalicylidene-1,2-cyclohexanediaminocobalt(II) catalyst [

42,

43,

44]. The enantiomeric purity of the intermediate

6R was found to be 97.8/2.2 er by HPLC equipped with a chiral stationary phase. Next, the chiral fluorohydrin intermediates

7R were synthesized from the corresponding chiral epoxides

6R by following the same procedure for the hydrofluorination found in

Scheme 3. The enantiomeric purity of intermediate

7R was determined to be 97.0/3.0 er by HPLC equipped with a chiral stationary phase. Finally, deoxyfluorination of the chiral fluorohydrin intermediates

7R using Pyfluor was performed to synthesize the chiral difluoro compounds

8S. The enantiomeric purity of the chiral difluoro compound

8S was determined to be 97.5/2.5 er by HPLC equipped with a chiral stationary phase. The synthesis of the

R enantiomer of

CBO5dF(4,5) was accomplished by following all the steps for the synthesis of the

S enantiomer of

CBO5dF(4,5) as in

Scheme 4, but in step viii of

Scheme 4, (

S,S)-(+)N,N’-bis(3,5-di-tert-butylsalicylidene-1,2-cyclohexanediaminocobalt(II) catalyst was used instead of (

R,R)-(+)N,N’-bis(3,5-di-tert-butylsalicylidene-1,2-cyclohexanediaminocobalt(II). The enantiomeric purity of the chiral difluoro compound

8R was determined to be 98.2/1.8 er by HPLC equipped with a chiral stationary phase.

The chiral epoxides

6R and

6S were synthesized from the racemic epoxide

6 by following the hydrolytic kinetic resolution (HKR) step viii in

Scheme 4. The enantiomeric purity of the target compound

8S in

Scheme 4 depends critically on the efficiency of this step. In this reaction, only half an equivalent of water is used, which preferentially and ideally exclusively hydrolyzes a single enantiomer of the racemic epoxide to a 1,2-dihydroxy compound while the other enantiomer remains inert to hydrolysis. The 1,2-dihydroxy compound and unreacted epoxide starting material are then separated by chromatography. The enantiomeric purity of the isolated epoxide can be determined by HPLC using a chiral stationary phase. On one occasion, while running this reaction, the racemic epoxide

6 was only partially hydrolyzed, and a batch of

6S with an enantiomeric purity determined to be 81.1/18.9 er was obtained. This sample was then used in the subsequent steps, where it was converted into

7S and

8R by following steps

ii and

vii in

Scheme 4. Their respective enantiomeric purity was determined to be 82.6/17.4 er and 80.9/19.1 er. The phase behavior of these enantiomerically impure compounds,

6S,

7S, and

8R, was also evaluated and compared with that of the enantiomerically pure ones.

The mesogenic properties of the target compounds in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 and the intermediates involved in their synthesis were evaluated by DSC measurements and POM.

We first present the phase behavior of the precursors involved in the synthesis of the difluoro compounds shown in

Figure 1. The phase behavior of the epoxy intermediates

2,

2S, and

2R (

Scheme 1 and

Scheme 2), which are reported in the literature, is presented here in

Table 1 [

19,

45,

46].

The phase behavior of the two epoxy intermediates

2S and

2R was found to be similar, but quite different from that of their racemate

2, as shown in

Table 1. All of them had a monotropic mesophase in the cooling cycle. The clearing point of the racemate was found to be higher than that of its individual enantiomers. A narrow blue phase was also observed in both chiral epoxy intermediates. The I → N transition temperature in the cooling cycle of the racemate was found to be similar to the I → BP transition temperature in the cooling cycle of its enantiomers. The phase behavior of the racemic epoxy intermediate

2 was found to be close to what is reported for this compound in the literature [

45]. The phase behavior of the optically active epoxy intermediate

2R with optical purity 84.4 ee % (92.2/7.8 er) is reported to be K 105.9 I 76.6 N*74.5 K, close to what was observed in this study. However, no indication of the presence of a blue phase was reported by them [

46]. Compound

2S is a known compound [

47].

Next, the phase behavior of the fluorohydrin intermediates

3,

3R, and

3S (

Scheme 1 and

Scheme 2) is presented in

Table 2.

The phase behavior of the two chiral fluorohydrin intermediates

3R and

3S was found to be similar but different from that of its racemate

3, as shown in

Table 2. Both enantiomers had a monotropic cholesteric mesophase in the cooling cycle with similar phase transition temperatures, whereas no mesophase was observed for the racemic fluorohydrin intermediate

3 by both DSC and POM measurements. The clearing point of the racemate

3 was also observed to be higher than that of its individual

3R and

3S enantiomers.

Finally, the phase behaviors of the racemic 4′-(2,3-difluoropropoxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile

CBO3dF(2,3) and its two enantiomers (

Figure 1), as determined by DSC measurements, are provided in

Table 3.

The racemate and enantiomers in

Table 3 all possess a monotropic phase transition. The racemate

CBO3dF(2,3) showed a monotropic nematic transition, and its enantiomers showed a monotropic cholesteric phase transition during the cooling cycle. The phase transition temperatures of the racemate and the enantiomers were comparable in this case. The mesophase was found to persist down to the ambient temperature after melting, but the samples eventually recrystallized over time on standing at ambient temperature as per POM.

Next, the mesogenic properties of the racemic 4′-(4,5-difluoropentyloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile as well as its enantiomers (

Figure 2) will be discussed. But before that, the phase behavior of intermediates involved in their synthesis will be discussed. The phase behavior of the epoxy intermediates

6,

6R, and

6S (

Scheme 3 and

Scheme 4) is presented in

Table 4. The phase behavior of the racemate

6 has been reported in the literature [

45].

As shown in

Table 4, the phase behavior of the two chiral epoxy intermediates

6R and

6S with high optical purity was found to be similar but different from that of its racemate

6. For the individual enantiomers, no mesophase was observed in either DSC or POM measurements. However, the racemate had a monotropic nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle with a clearing point lower than that of its enantiomers. The phase behavior of the enantiomerically impure

6S enantiomer was also determined. No mesophase was observed in it, as that of its pure enantiomers and the phase transition temperatures were found to be between those of its pure enantiomers and its racemic compound.

Next, the phase behavior of the fluorohydrin intermediates

7,

7R, and

7S (

Scheme 3 and

Scheme 4) is presented in

Table 5.

From the study of the phase behavior of the racemic, pure enantiomers, and enantiomerically impure fluorohydrin intermediates shown in

Table 5, it was found that the enantiomers (enantiomerically pure and impure) and the racemate all had enantiotropic mesophase transitions. The racemate had an enantiotropic nematic phase, whereas the enantiomers had an enantiotropic chiral nematic phase. The N (or N* for enantiomers) → I transition in the heating cycle and I → N (or N* for enantiomers) transition in the cooling cycle for all of them (racemic, pure enantiomers, and enantiomerically impure fluorohydrin intermediates,

Table 5) were found to be similar. Meanwhile, the K → N (or N* for enantiomers) transition temperature (melting point) of pure enantiomers

7R and

7S was lower than that of the racemate

7. The K → N* transition temperature (melting point) of enantiomerically impure compound

7S was even lower than that of its racemate

7 and enantiomerically pure compounds

7R and

7S.

Finally, the phase behavior of the racemic 4′-(4,5-difluoropentyloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile CBO5dF(4,5), as well as its enantiomers (

Figure 2), determined by DSC measurements, is shown in

Table 6.

In

Table 6, it can be seen that the racemic

CBO5dF(4,5) has a monotropic nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle with a clearing point higher than that of the enantiomers (pure and impure). The two pure

S and

R enantiomers of

CBO5dF(4,5) had similar phase transition temperatures and a monotropic chiral nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle. The impure

R enantiomer of

CBO5dF(4,5) also has a monotropic chiral nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle, but its K → I transition temperature was found to be broad both by DSC and POM, and between the K → I transition temperature of the racemate and of the pure enantiomers of

CBO5dF(4,5). Meanwhile, the I → N (or N* for enantiomers) transition temperature in the cooling cycle for all of them (racemic, pure enantiomers, and enantiomerically impure

CBO5dF(4,5)) was found to be similar. For the samples with a superscript ‘b’, the mesophase was found to persist down to ambient temperature after melting, but all the samples eventually recrystallized over time on standing at ambient temperature as per POM.

The difference in the phase behavior between the enantiomers and racemic compound can be explained by the difference in the packing of chiral molecules in the enantiomer and racemic compound. The enantiomers and the racemic compounds possess different organizations (lattice symmetry and relative arrangement of the molecules), which give rise to differences in the observed phase behavior. In some cases, these differences are subtle (

Table 3), whereas in others, the disparities are pronounced enough that, without additional information, the two samples might appear to be entirely different substances (

Table 2 and

Table 4) [

48].

The difference in the phase behavior of enantiomerically pure compounds and enantiomerically impure compounds presented in this work can be explained by the binary phase diagrams. Mixtures of enantiomers forming racemic compounds yield a phase diagram. Many phase diagrams of enantiomer mixtures exhibiting racemic compound formation exist. The shape of these diagrams depends on whether the racemic compound’s melting point is greater, lower, or equal to that of the enantiomers. In phase diagrams of enantiomer mixtures, it has been seen that certain mixtures of enantiomers can have a melting point lower than that of both racemate and pure enantiomers. This might explain the lower melting point of enantiomerically impure

7S versus the melting point of racemic

7 and enantiomerically pure

7S in

Table 5 [

48].

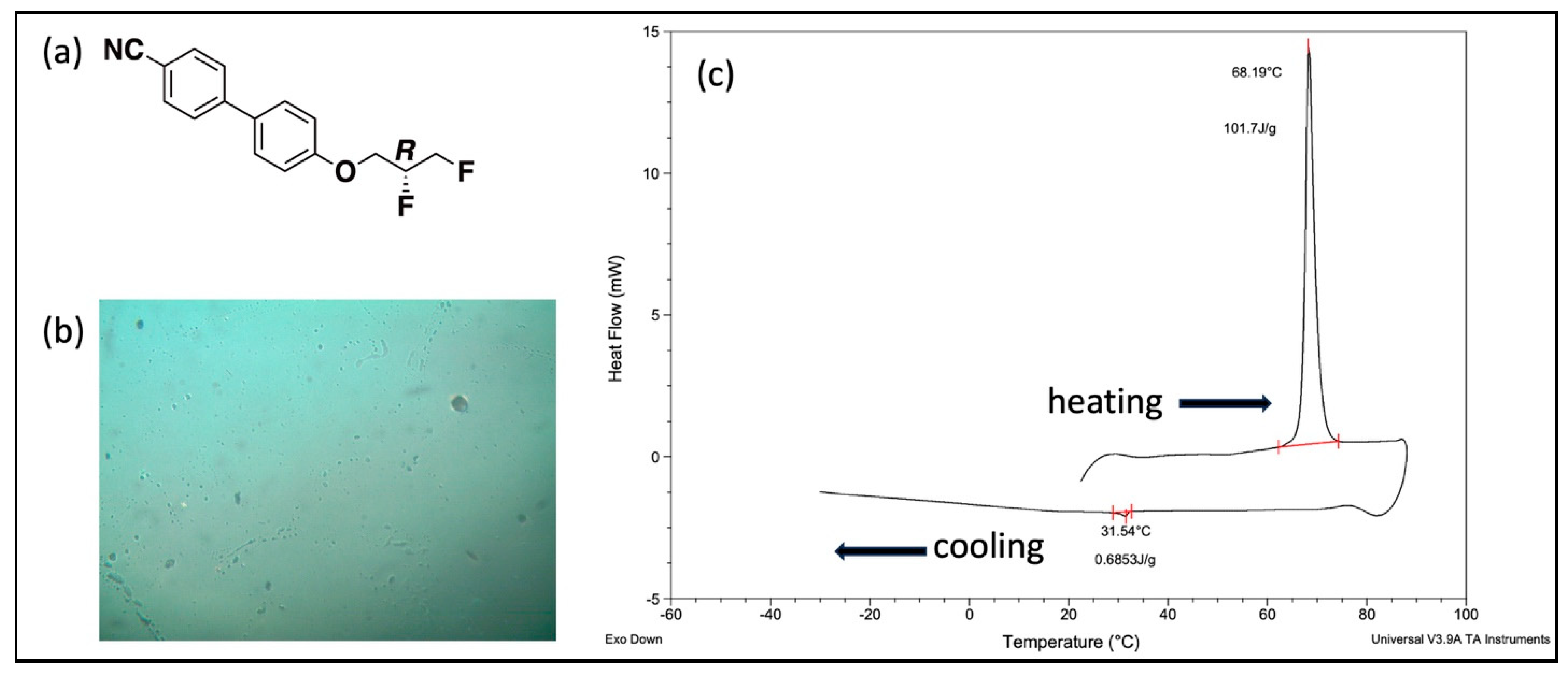

Figure 4 shows the DSC thermogram of a typical monotropic cholesteric transition observed for

CBO3dF(2,3) R enantiomer, along with its structure and optical image.

Next, since the phase behavior of the nonfluorinated alkoxycyanobiphenyls and the monofluorine tail-terminated alkoxycyanobiphenyls is already reported in the literature, the phase behavior of nonfluorinated alkoxycyanobiphenyls and monofluorine tail-terminated alkoxycyanobiphenyls was compared with that of the racemic difluoroalkoxycyanobiphenyls synthesized in this work, and the data are represented in

Table 7.

In

Table 7, we can see that 4′-(propyloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile

CBO3 has a monotropic nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle. Fluorine tail-terminated analog

CBO3F(3) and racemic difluorinated analog

CBO3dF(2,3) also had a monotropic nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle. A decrease in the I → N transition temperature in the cooling cycle was observed as fluorine was introduced from

CBO3 to

CBO3F(3) and then from

CBO3F(3) to

CBO3dF(2,3).

Next, in the 4′-(pentyloxy)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile CBO5 series, both CBO5 and monofluorine tail-terminated analog CBO5F(5) had an enantiotropic nematic mesophase, but the racemic difluorinated analog CBO5dF(4,5) had a monotropic nematic mesophase in the cooling cycle. The I → N transition temperature in the cooling cycle decreased as fluorine was introduced from CBO5 to CBO5F(5) and then from CBO5F(5) to CBO5dF(4,5). However, no such pattern of increase or decrease was observed in the melting point (K → N) transition in the heating cycle for enantiotropic, K → I transition in the heating cycle for monotropic) of these compounds.

Examination of the phase behavior of the enantiomers of

CBO3dF(2,3) and

CBO5dF(4,5) showed that they had a monotropic cholesteric transition in the cooling cycle that stayed cholesteric until room temperature but eventually recrystallized at room temperature. The binary mixtures of the enantiomers were made, and their mesogenic properties were examined to see if recrystallization could be inhibited. The binary mixtures could have been made by mixing the constituents in various possible ratios. However, to begin with, the 1:1 wt/wt binary mixtures of each of the enantiomers of

CBO3dF(2,3) and

CBO5dF(4,5) were made. All of the binary mixtures of the compounds were cholesteric at room temperature when they were made. The phase behavior of the mixtures was evaluated when they were cholesteric at room temperature and is shown in

Table 8, along with the phase behavior of the individual components. In

Table 8, we can see that all the mixtures had similar phase transition temperatures. However, for two mixtures,

CBO3dF(2,3),(+)

S and

CBO5dF(4,5),(-)

S and

CBO3dF(2,3),(-)

R and

CBO5dF(4,5),(+)

R, the formation of a blue phase was observed in the cooling cycle. Unfortunately, all the mixtures recrystallized on standing at room temperature over time. Hence, the set of mixtures studied thus far has not solved the issue of recrystallization.

Calculated dipole moments for the effects of vicinal fluorination on the terminal alkoxy tail group are summarized in

Figure 5. The DFT-calculated average dipole moments for

CBO3,

CBO5, and their fluorinated derivatives are shown in

Figure 5A,B. As the degree of fluorination increases, the average dipole moment of

CBO3- and

CBO5-derived mesogens decreases monotonically. Monosubstitution of the alkoxy tail of

CBO3 (8.83 D) and

CBO5 (8.84 D) [

19] with fluorine, resulting in

CBO3F(3) (8.50 D) [

9] and

CBO5F(5) (8.55 D) [

19], lowers the calculated dipole moment by 0.33 D and 0.29 D, respectively. When considering racemates of

CBO3dF(2,3) and

CBO5dF(4,5), further fluorination of the alkoxy tail to produce difluorinated

CBO3dF(2,3) (7.0 D) and

CBO5dF(4,5) (7.93 D) leads to a decrease in dipole moment of

CBO3F(3) (8.50 D) and

CBO5F(5) (8.55 D) by 1.50 D and 0.62 D, respectively. These changes in the dipole moment qualitatively align with the nematic–isotropic phase transition temperatures reported in

Table 7.

Increasing the alkoxy tail length from three to five carbon atoms, as shown in

Figure 5A,B, had a variable effect on the dipole moment. The average calculated dipole moment of nonfluorinated mesogens

CBO3 (8.83 D) and

CBO5 (8.84 D) [

19] differed by only 0.01 D. Similarly, for monofluorinated species, including

CBO3F(3) (8.50 D) [

9] and

CBO5F(5) (8.55 D) [

19], the dipole moment differed by approximately 0.05 D. However, for difluorinated species, the dipole moment of

CBO5dF(4,5) (7.93 D) was notably larger than the dipole moment of

CBO3dF(2,3) (7.0 D) by 0.93 D. One possible explanation for the higher dipole moment of

CBO5dF(4,5) is the greater separation between the alkoxy oxygen and the fluorine-substituted tail, which enhances charge separation and reduces vector cancelation between their roughly colinear dipoles (

Figure 5D) relative to

CBO3dF(2,3).

During assessment of enantiomeric purity, we observed that the regioselective opening of the chiral epoxy intermediates by nucleophiles (e.g., fluoride anions;

2S →

3R in

Scheme 2) preserves the enantiomeric purity of the epoxy intermediate (e.g.,

2S) compared to that of the fluorohydrin intermediate (e.g.,

3R). In our prior publications [

12,

19], the hydroxy enantiomers were synthesized by regioselective opening of the chiral epoxy intermediates by nucleophiles like carbanions. There, the enantiomeric purity of the epoxy intermediate was also found to be comparable to that of the product after epoxide opening, the hydroxy intermediate. In those previous publications [

12,

19], the chiral hydroxy intermediate synthesized after epoxide opening was converted to a chiral fluoro-compound by deoxyfluorination using Pyfluor and base like DBU. Although the mechanism of deoxyfluorination by the employed method is described as an S

N2 reaction, a slight difference in the enantiomeric purity of the chiral fluoro-compound and the chiral hydroxy intermediate was observed. The acronym S

N2 stands for second-order nucleophilic substitution reaction. If we look at

Figure 6, which explains the mechanism of deoxyfluorination using Pyfluor and DBU reagents, it is shown that the hydroxy intermediate reacts with Pyfluor and DBU to form a sulfonate ester intermediate and a reactive amidine hydrogen fluoride [

28]. The sulfonate ester group in the sulfonate ester intermediate is replaced by fluorine from the amidine hydrogen fluoride complex in an S

N2 fashion, resulting in the inversion of configuration at the stereocenter [

28].

However, in this study, when the chiral fluorohydrin intermediates (for example,

3R →

4S in

Scheme 2) were converted to chiral difluorocompounds by utilizing the same method of deoxyfluorination, the enantiomeric purity of the chiral fluorohydrin intermediate was similar to that of the chiral difluoro-product. This observation could be explained by the phenomenon called the

gauche effect.

Generally, two atoms or groups, each one present on the adjacent carbon atoms, prefer anti-conformation (180° separation) to minimize steric hindrance. However, in some compounds containing certain electronegative atoms or groups (like fluorine), the

gauche conformation is favorable (60° separation). This phenomenon is known as the

gauche effect. This is due to favorable orbital overlap between a filled bonding orbital (like a C-H bond) and an empty antibonding orbital (like a C-F bond) of the adjacent carbon. The compound adopts a conformation that has the maximum number of

gauche interactions [

49,

50].

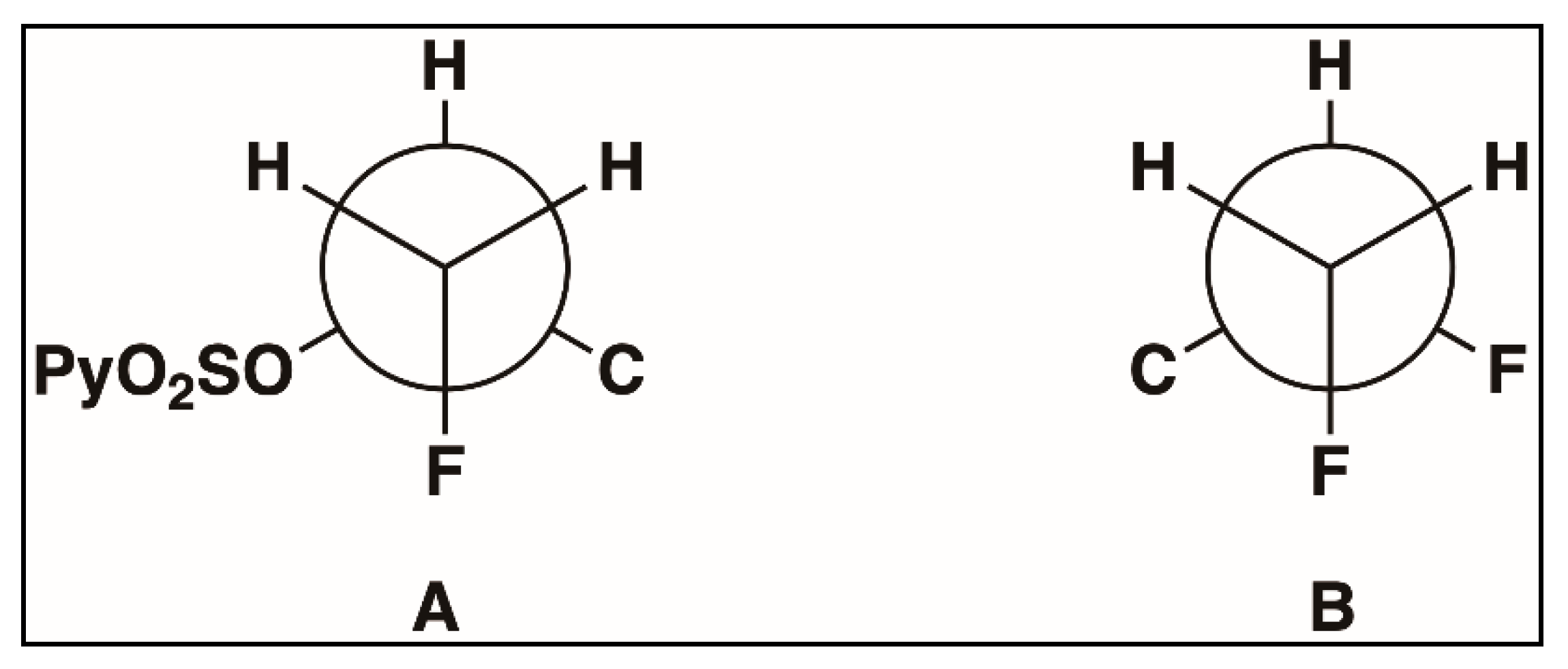

It is reported that on 1,2-(diarylsulfonate)ethane, despite the bulkiness of the sulfonates, the molecule adopts a

gauche conformation [

51]. Hence, amongst various possible conformations, the sulfonate ester intermediate in

Figure 6 adopts the low-energy conformation in which the 2-pyridine sulfonate group and fluorine group are

gauche to each other (

Figure 7A) because this is the only conformation that allows the maximum number of orbital overlaps (two) between a filled bonding orbital (like a C-H bond) and an empty antibonding orbital (like a C-F bond and C-OSO

2Py bond) of the adjacent carbon. Now, when these fluorohydrin intermediates undergo deoxyfluorination (for example,

3R →

4S in

Scheme 2), clean inversion takes place, and the result is that the difluoro-products are as enantiomerically pure as the fluorohydrin intermediates. Therefore, in this study, the enantiomeric purity of all the chiral difluoro-products was found to be similar to that of their corresponding chiral fluorohydrin intermediates.