Synthesis, Reaction Process, and Mechanical Properties of Medium-Entropy (TiVNb)2AlC MAX Phase

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Fabrication Process

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

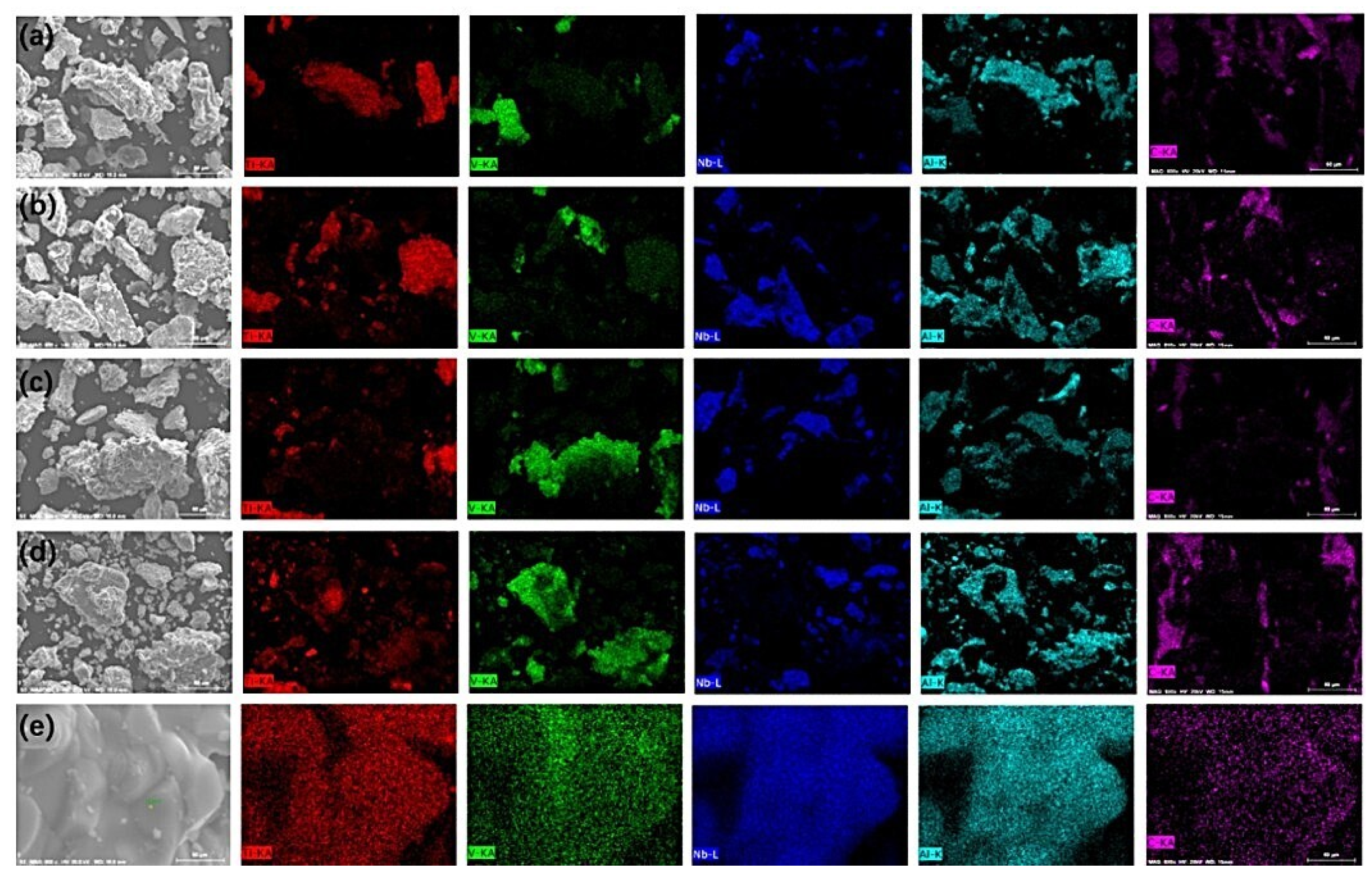

3.1. The Effect of the Sintering Process on Purity

3.2. The Phase Evolution During the Reaction

3.3. Mechanical Properties

3.4. Friction and Wear Performance

| Properties | (TiVNb)2AlC (This Paper) | Ti2AlC [56] | V2AlC [57] | (W-Alloys)-Nb2AlC-Sn [58] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wear ratess (m3/Nm) | 0.89 × 10−14–2.54 × 10−14 | 10−14–5.5 × 10−13 | 10−16–2.07 × 10−13 | 2.51 × 10−13–6.49 × 10−13 |

| The counter | Bearing steel | Inc718 | Al2O3 | Si3N4 |

| Temperature (°C) | R.T.–400 | R.T.–550 | R.T.–800 | R.T. |

| Linear velocity (m/s) | 0.1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1–0.2 |

| Load (N) | 4 | 3 | 10 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Xing, Y.; Dai, F.-Z.; Wang, H.; Su, L.; Miao, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, X.; Yao, L.; et al. High-entropy ceramics: Present status, challenges, and a look forward. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 385–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, Z.Y.; Jian, N.; Yao, J.H.; Gao, M.X.; Pan, H.G.; Liu, Y.F. Synthesis and Catalytic Effects of Solid-Solution MAX-phase (Ti0.5V0.5)3AlC2 on Hydrogen Storage Performance of MgH2. Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 35, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlqvist, M.; Rosen, J. The Rise of MAX Phase Alloys—Large-Scale Theoretical Screening for the Prediction of Chemical Order and Disorder. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 10958–10971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, D.; Cao, J.; Fang, W.; Bao, Y.; Liu, B. Recent advances in high-entropy ceramics: Design principles, structural characteristics, and emerging properties. Extrem. Mater. 2025, 1, 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Fan, S.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Bei, G. Ti3AlC2−yNy carbonitride MAX phase solid solutions with tunable mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Guo, A.X.Y.; Zhan, S.; Liu, C.-T.; Cao, S.C. Refractory high-entropy alloys: A focused review of preparation methods and properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 142, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Cai, D.D.; Sun, X.; Huang, H.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.Z.; Hu, Q.M.; Vitos, L.; Ding, X.D. Solid solution strengthening of high-entropy alloys from first-principles study. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 121, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhao, S.; Han, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, P.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; et al. Progress in Structural Tailoring and Properties of Ternary Layered Ceramics. J. Inorg. Mater. 2023, 38, 845–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Ying, G.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, P. From structural ceramics to 2D materials with multi-applications: A review on the development from MAX phases to MXenes. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 1194–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.W.; El-Raghy, T. The MAX Phases: Unique New Carbide and Nitride Materials. Am. Sci. 2001, 89, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.W.; El-Raghy, T. Synthesis and Characterization of a Remarkable Ceramic: Ti3SiC2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1996, 79, 1953–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevislov, S.N.; Sokolova, T.V.; Stolyarova, V.L. The Ti3SiC2 max phases as promising materials for high temperature applications: Formation under various synthesis conditions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 267, 124625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsipoor, A.; Farvizi, M.; Razavi, M.; Keyvani, A.; Mousavi, B.; Pan, W. Hot corrosion behavior of Cr2AlC MAX phase and CoNiCrAlY compounds at 950 °C in presence of Na2SO4+V2O5 molten salts. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovic, M.; Barsoum, M. MAX Phases: Bridging the gap Between Metals and Ceramics. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2013, 92, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhai, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L. Layered ternary MAX phases and their MX particulate derivative reinforced metal matrix composite: A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 856, 157313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.M. Progress in research and development on MAX phases: A family of layered ternary compounds. Int. Mater. Rev. 2013, 56, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Duan, X.; Jia, D.; Zhou, Y.; van der Zwaag, S. On the formation mechanisms and properties of MAX phases: A review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 3851–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, S. MAX phase coatings: Synthesis, protective performance, and functional characteristics. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 1689–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huang, Q. Recent Progress and Prospects of Ternary Layered Carbides/Nitrides MAX Phases and Their Derived Two-Dimensional Nanolaminates MXenes. J. Inorg. Mater. 2020, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Radovic, M. Elastic and Mechanical Properties of the MAX Phases. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2011, 41, 195–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, M.; Chang, K.; Zha, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Persson, P.O.A.; Hultman, L.; Eklund, P. Multielemental single-atom-thick A layers in nanolaminated V2(Sn, A)C (A = Fe, Co, Ni, Mn) for tailoring magnetic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 117, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chong, H.; Sun, S.; Yang, J.; Yao, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; Cui, W. Synthesis and characterizations of solid-solution i-MAX phase (W1/3Mo1/3R1/3)2AlC (R = Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er and Y) and derivated i-MXene with improved electrochemical properties. Scr. Mater. 2022, 213, 114596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Fan, G.; Fang, X.; Han, P. Effects of different alloying additives X (X = Si, Al, V, Ti, Mo, W, Nb, Y) on the adhesive behavior of Fe/Cr2O3 interfaces: A first-principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 109, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, J.; Luo, K.; Li, Y.; Chang, K.; Chen, K.; Zhou, J.; Rosen, J.; Hultman, L.; Eklund, P. Element Replacement Approach by Reaction with Lewis Acidic Molten Salts to Synthesize Nanolaminated MAX Phases and MXenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4730–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anasori, B.; Luhatskaya, M.R.; Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. Recent Progress in Theoretical Prediction, Preparation, and Characterization of Layered Ternary Transition-Metal Carbides. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2009, 39, 415–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, M.; Wilhelmsson, O.; Palmquist, J.P.; Jansson, U.; Mattesini, M.; Li, S.; Ahuja, R.; Eriksson, O. Electronic structure and chemical bonding in Ti2AlC investigated by soft x-ray emission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. 2011, 74, 195108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Hu, F.; Ji, J. High entropy six-component solid solution (Ti0.5Nb0.15Zr0.1Mo0.1Ta0.1W0.05)2AlC: A novel synthesis approach and its mechanical properties. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49 Pt B, 39719–39723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Xia, Y.; Teng, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H. Synthesis and enhanced mechanical properties of compositionally complex MAX phase. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 4658–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. The corrosion behavior of multicomponent porous MAX phase (Ti0.25Zr0.25Nb0.25Ta0.25)2AlC in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 2023, 222, 111430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.-F.; Xue, Y.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Xue, L.; Yu, H. Synthesis of a high-entropy (TiVCrMo)3AlC2 MAX and its tribological properties in a wide temperature range. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 4684–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Soomro, S.A.; Jahanger, M.I.; Zhou, Y.; Chu, L.; Feng, Q.; Hu, C. Factors influencing synthesis and properties of MAX phases. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 3427–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Chen, K.; Guo, J.; Zhou, H.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Combustion synthesis of ternary carbide Ti3AlC2 in Ti–Al–C system. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2003, 23, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, J.; Bao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. In-situ reaction synthesis and decomposition of Ta2AlC. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 99, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, G.; Bai, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, X.; Ke, P.; Wang, A. MAX phase forming mechanism of M–Al–C (M = Ti, V, Cr) coatings: In-situ X-ray diffraction and first-principle calculations. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 143, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijuade, A.A.; Bellevu, F.L.; Singh, S.K.D.; Rahman, M.M.; Arnett, N.; Okoli, O.I. Processing of V2AlC MAX phase: Optimization of sintering temperature and composition. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50 Pt B, 3733–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, A.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L. Synthesis and oxidation resistance of V2AlC powders by molten salt method. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2017, 14, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Travitzky, N.; Hu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Greil, P. Reactive Hot Pressing and Properties of Nb2AlC. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 2396–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Zu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. A multicomponent porous MAX phase (Ti0.25Zr0.25Nb0.25Ta0.25)2AlC: Reaction process, microstructure and pore formation mechanism. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 2167–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lóh, N.J.; Simão, L.; Faller, C.A.; De Noni, A.; Montedo, O.R.K. A review of two-step sintering for ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 12556–12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, P.; Beckers, M.; Jansson, U.; Högberg, H.; Hultman, L. The Mn+1AXn phases: Materials science and thin-film processing. Thin Solid Film. 2010, 518, 1851–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingchu, M.; Xuewen, X.U.; Jiaoqun, Z.; Ing, L.J. Fabrication and microstructure of Ti3AlC2. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 32, 897–900. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, G.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, Z. Synthesis and strengthening mechanism of (Ti0.9Nb0.03Ta0.03W0.03)3SiC2/Al2O3 composite ceramics by doping NbC, TaC and WC powders. Vacuum 2023, 215, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri-Shahroudi, F.; Ghasemi, B.; Abdolahpour, H. Sintering behavior of Cr2AlC MAX phase synthesized by Spark plasma sintering. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2022, 19, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cui, H.; Han, Y.; Hou, N.; Wei, N.; Ding, L.; Song, Q. Effect of carbon reactant on microstructures and mechanical properties of TiAl/Ti2AlC composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2017, 684, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, P.Y.; Zhao, W.J.; Ma, S.H.; Hou, J.H.; He, Q.F.; Wu, C.L.; Chen, H.A.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Q.; et al. Lattice distortion enabling enhanced strength and plasticity in high entropy intermetallic alloy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirathipviwat, P.; Sato, S.; Song, G.; Bednarcik, J.; Nielsch, K.; Jung, J.; Han, J. A role of atomic size misfit in lattice distortion and solid solution strengthening of TiNbHfTaZr high entropy alloy system. Scr. Mater. 2022, 210, 114470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Y.; Wang, X.T.; Ma, Y.J.; Chen, J.L.; Zhao, X.J.; Cheng, J.; Xu, T.R.; Zhao, W.L.; Song, X.Y.; Wu, S.; et al. Strong solid solution strengthening caused by severe lattice distortion in body-centered cubic refractory high-entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 2025, 263, 116671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Meng, F.L.; Wang, J.Y. Strengthening of Ti2AlC by substituting Ti with V. Scr. Mater. 2005, 53, 1369–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; He, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Bao, Y.; Zhou, Y. In Situ Reaction Synthesis and Mechanical Properties of V2AlC. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 4029–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, K.; Zhu, J.; Tian, S. Rapid synthesis of highly pure Nb2AlC using the spark plasma sintering technique. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2018, 120, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y. Characteristics of tribo-oxidation surface evolution in molybdenum−tungsten−vanadium hot-work die steel. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 4097–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Duan, X.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Wang, E.; Hou, X. A new strategy for long-term complex oxidation of MAX phases: Database generation and oxidation kinetic model establishment with aid of machine learning. Acta Mater. 2022, 241, 118378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Z.-S. Perspective on high entropy MXenes for energy storage and catalysis. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 1735–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Filimonov, D.; Zaitsev, V.; Palanisamy, T.; Barsoum, M.W. Ambient and 550 °C tribological behavior of select MAX phases against Ni-based superalloys. Wear 2008, 264, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, Q.; Ke, P.; Wang, A. Microstructure evolution of V−Al–−C coatings synthesized from a V2AlC compound target after vacuum annealing treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 661, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Yin, X.; Han, W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Xiong, B.; Yang, K.; Hao, Y. Important explorations of the sliding tribological performances of micro/nano−structural interfaces: Cross−shaped microconcave and the nanoNb2AlC−Sn. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 142, 106738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Cao, G.; Pan, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, B.; Hu, J. Recent progress in synthesis of MAX phases and oxidation & corrosion mechanism: A review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2024, 12, 765–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature/°C | Phase Composition |

|---|---|

| R.T. | Ti, V, Nb, Al, C |

| 750 | Ti, V, Nb, C, V3Al, TiAl3 |

| 850 | V, Nb, C, V3Al, TiAl3, TiAl2, TiAl, NbAl3, Ti3Al |

| 950 | V, Nb, C, V3Al, TiAl3, TiAl, NbAl3, Ti3Al |

| 1050 | Nb, C, TiAl, Nb2Al, NbAl3, V3Al, Ti3Al |

| 1150 | Nb, C, TiAl, Nb2Al, V3Al, Ti3Al |

| 1250 | C, NbAl3, TiAl, Nb2Al, MC, M2AlC, |

| 1350 | Nb2Al, MC, M2AlC, |

| 1450 | MC, M2AlC |

| 1550 | MC, M2AlC |

| Temperature/°C | Percentage of Elements/% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | V | Nb | Al | C | Total | |

| 1450 | 17.02 | 15.84 | 15.86 | 25.18 | 26.10 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Che, L.; Bao, M.; Sun, Z.; Cao, Y. Synthesis, Reaction Process, and Mechanical Properties of Medium-Entropy (TiVNb)2AlC MAX Phase. Crystals 2025, 15, 903. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100903

Che L, Bao M, Sun Z, Cao Y. Synthesis, Reaction Process, and Mechanical Properties of Medium-Entropy (TiVNb)2AlC MAX Phase. Crystals. 2025; 15(10):903. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100903

Chicago/Turabian StyleChe, Lexing, Mingdong Bao, Zhihua Sun, and Yingwen Cao. 2025. "Synthesis, Reaction Process, and Mechanical Properties of Medium-Entropy (TiVNb)2AlC MAX Phase" Crystals 15, no. 10: 903. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100903

APA StyleChe, L., Bao, M., Sun, Z., & Cao, Y. (2025). Synthesis, Reaction Process, and Mechanical Properties of Medium-Entropy (TiVNb)2AlC MAX Phase. Crystals, 15(10), 903. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100903