Metal–Organic Framework for Plastic Depolymerization and Upcycling

Abstract

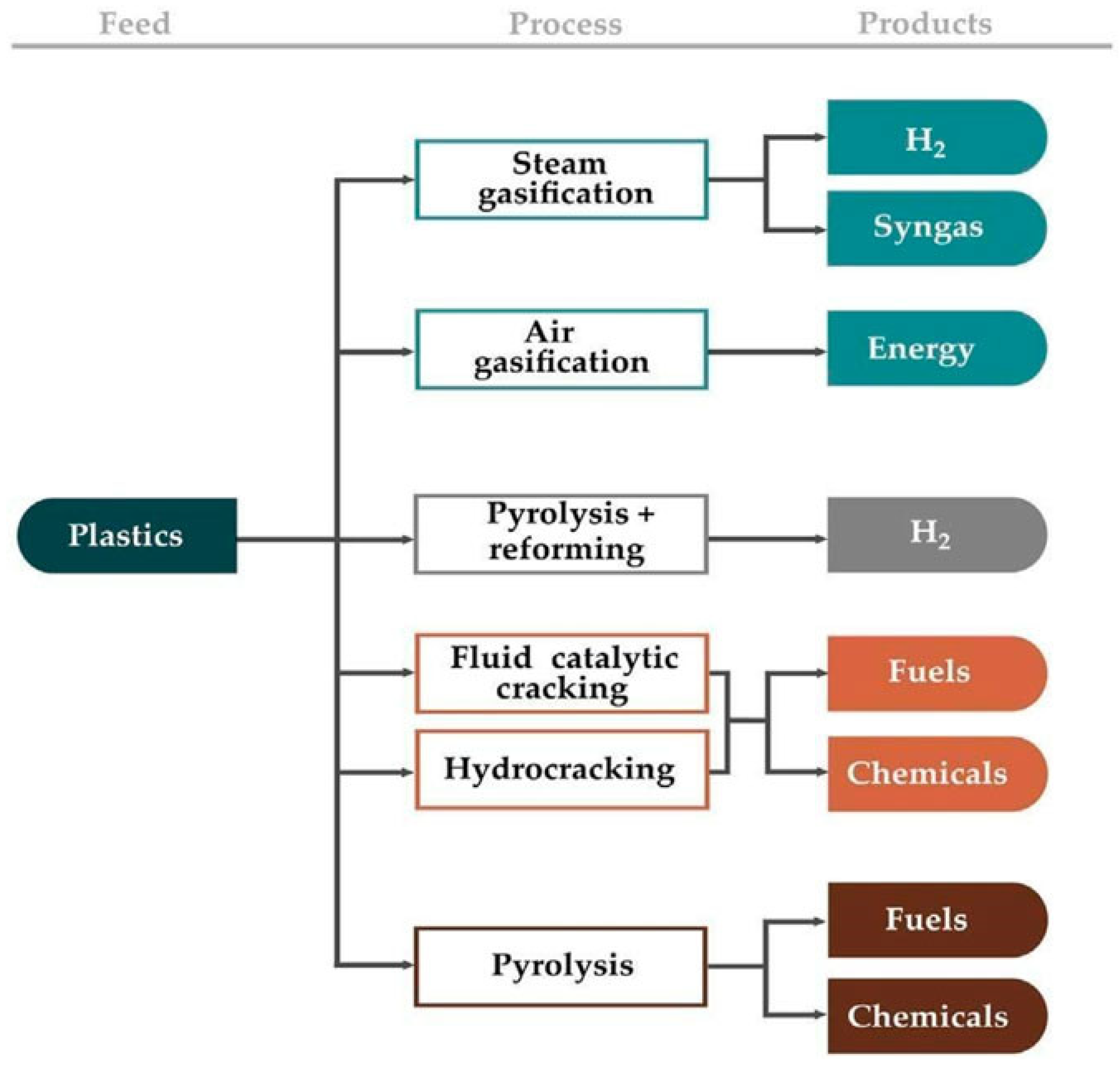

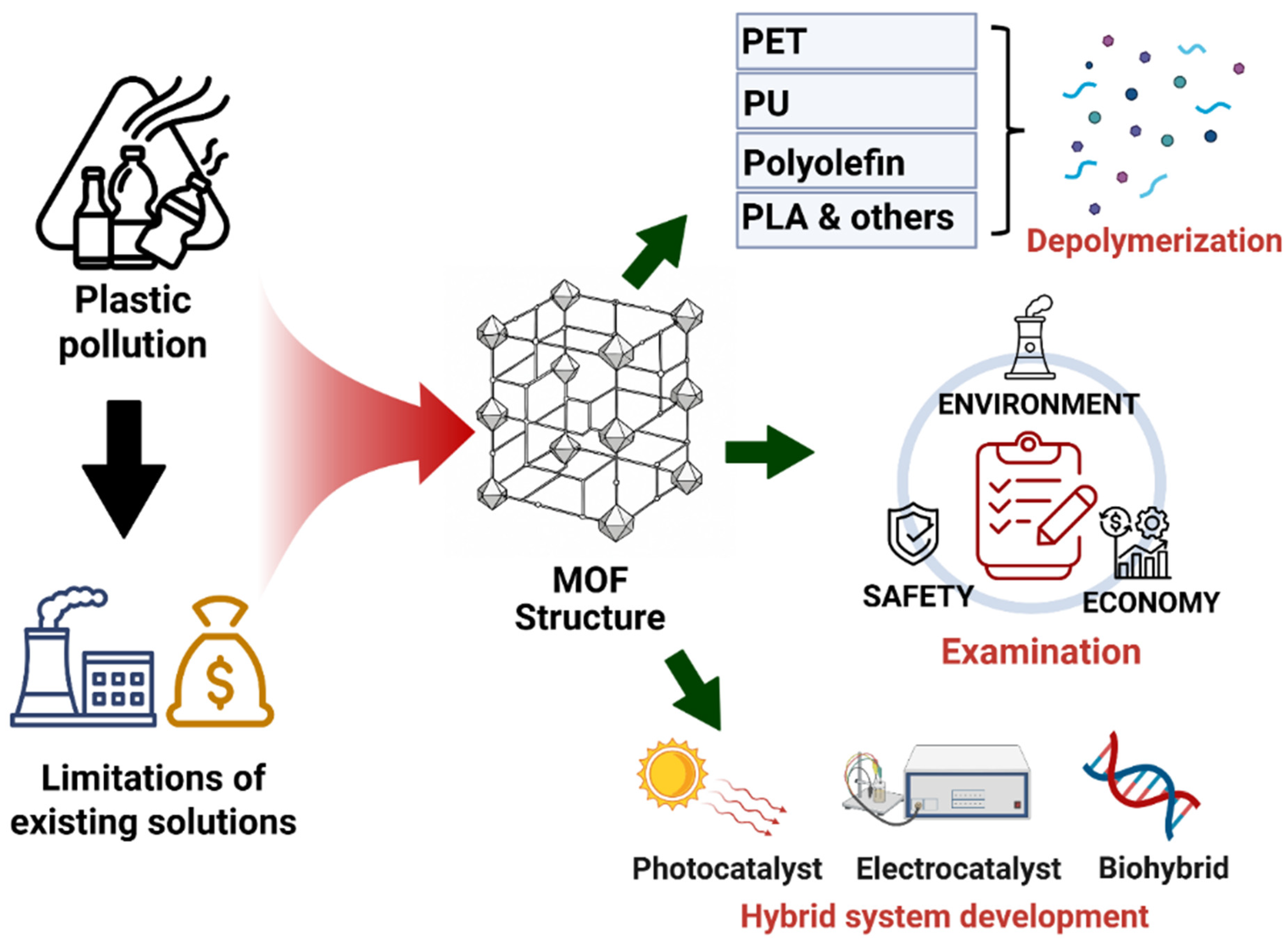

1. Introduction

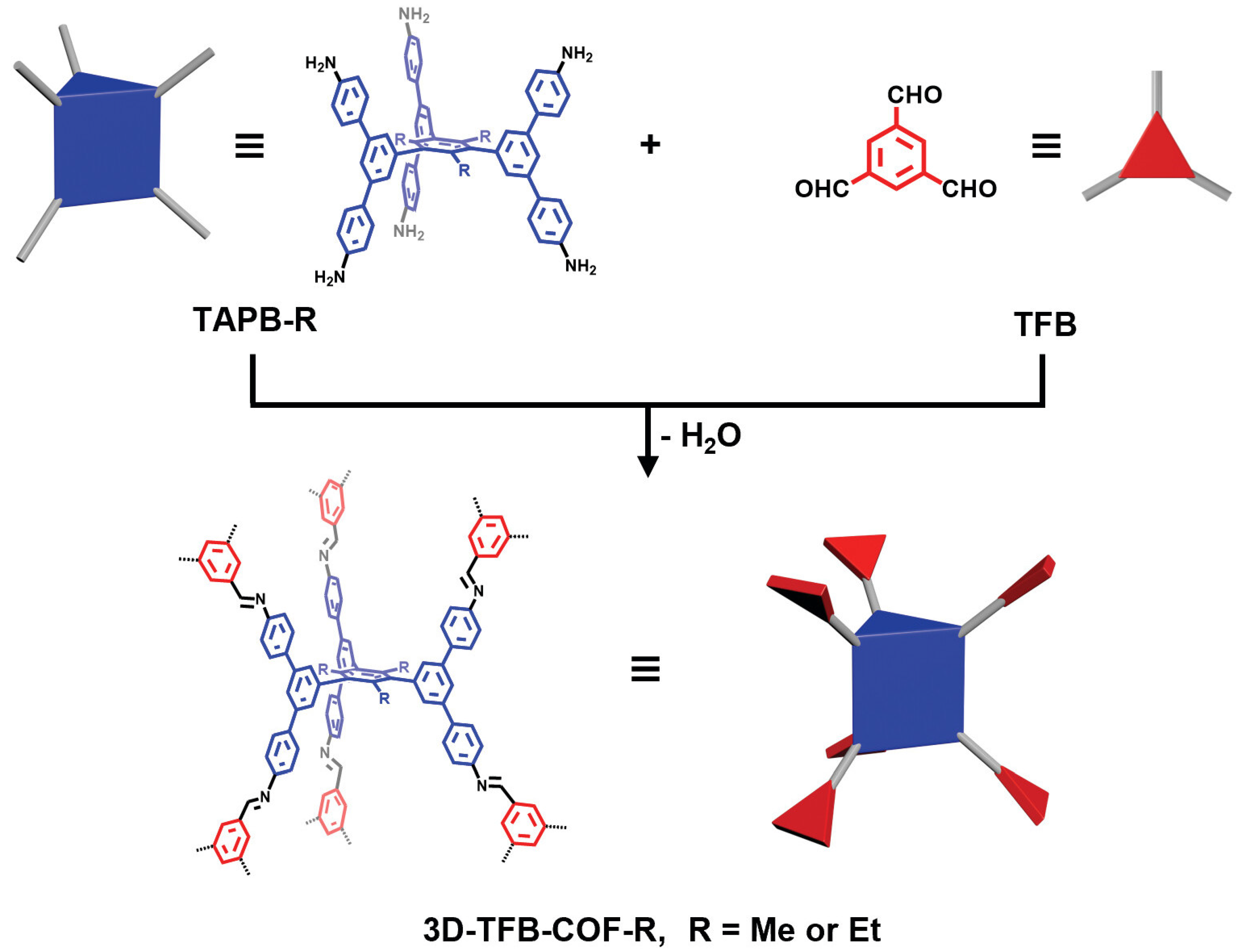

2. Design Principles of MOF Catalysts for Polymer Depolymerization and Upcycling

2.1. Framework Crystallinity, Porosity, and Accessible Surface

2.2. Coordination Environments and Active-Site Engineering

2.3. Stability Under Depolymerization Conditions

2.4. Functional Classification of MOF Catalysts for Polymer Deconstruction

3. Scalable Manufacturing and Functionalization of MOF Catalysts

3.1. Synthesis Routes and Scale-Up Considerations

3.2. Sustainable and Scalable Manufacturing

3.3. Post-Synthetic Functionalization and Active-Site Modulation

3.4. Recent Trends in the Utilization of MOF-Based Materials for Plastic Depolymerization and Upcycling

4. Mechanistic Basis of MOF-Mediated Plastic Degradation

4.1. Polymer Adsorption and Diffusion in MOF Pores

4.2. Nucleophilic Scission Pathways

4.3. Photocatalytic and Oxidative Degradation

5. Depolymerization and Upcycling of Major Plastic Classes

5.1. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Depolymerization

5.2. Polyurethane (PU) Chemical Recycling

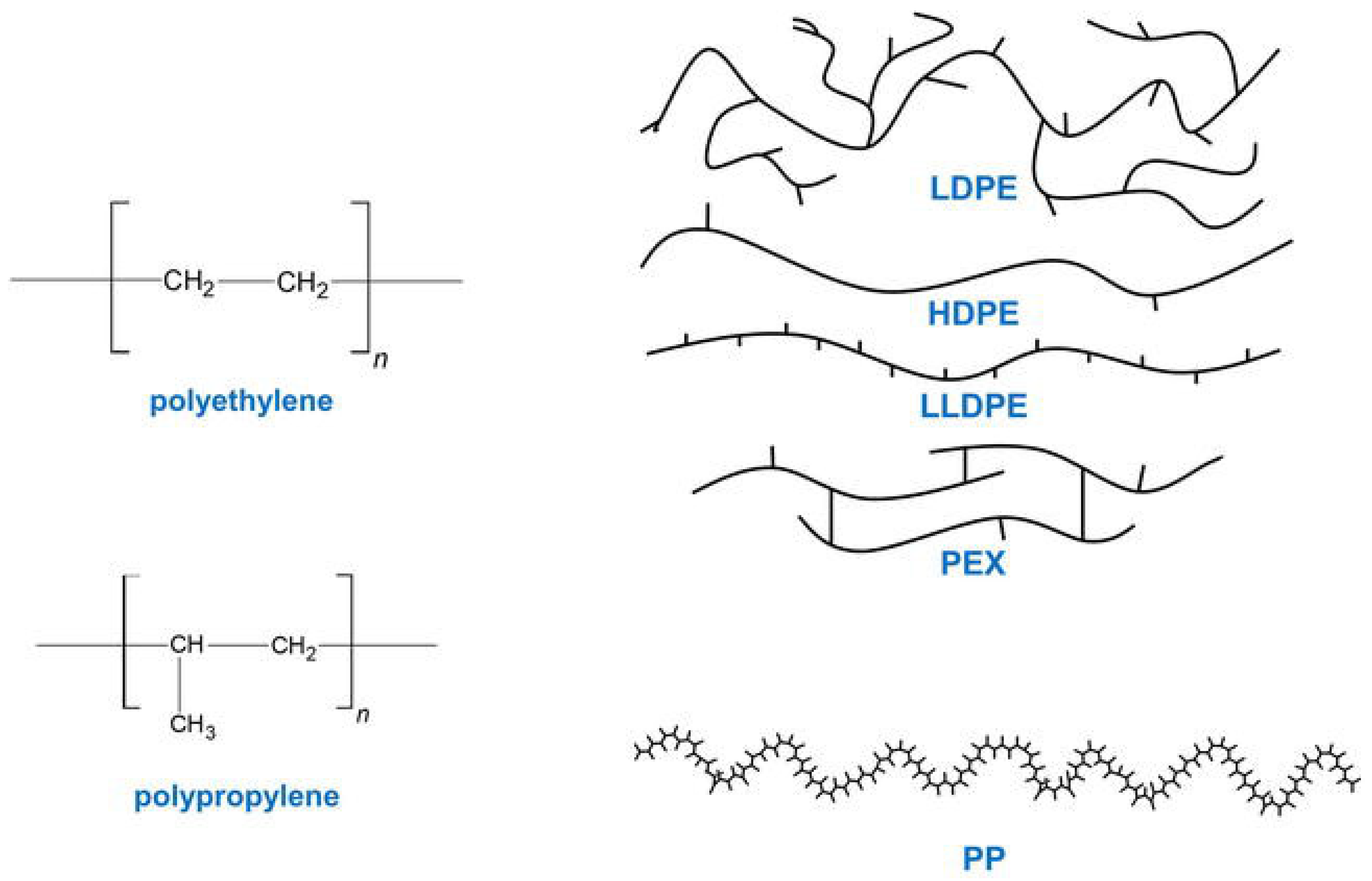

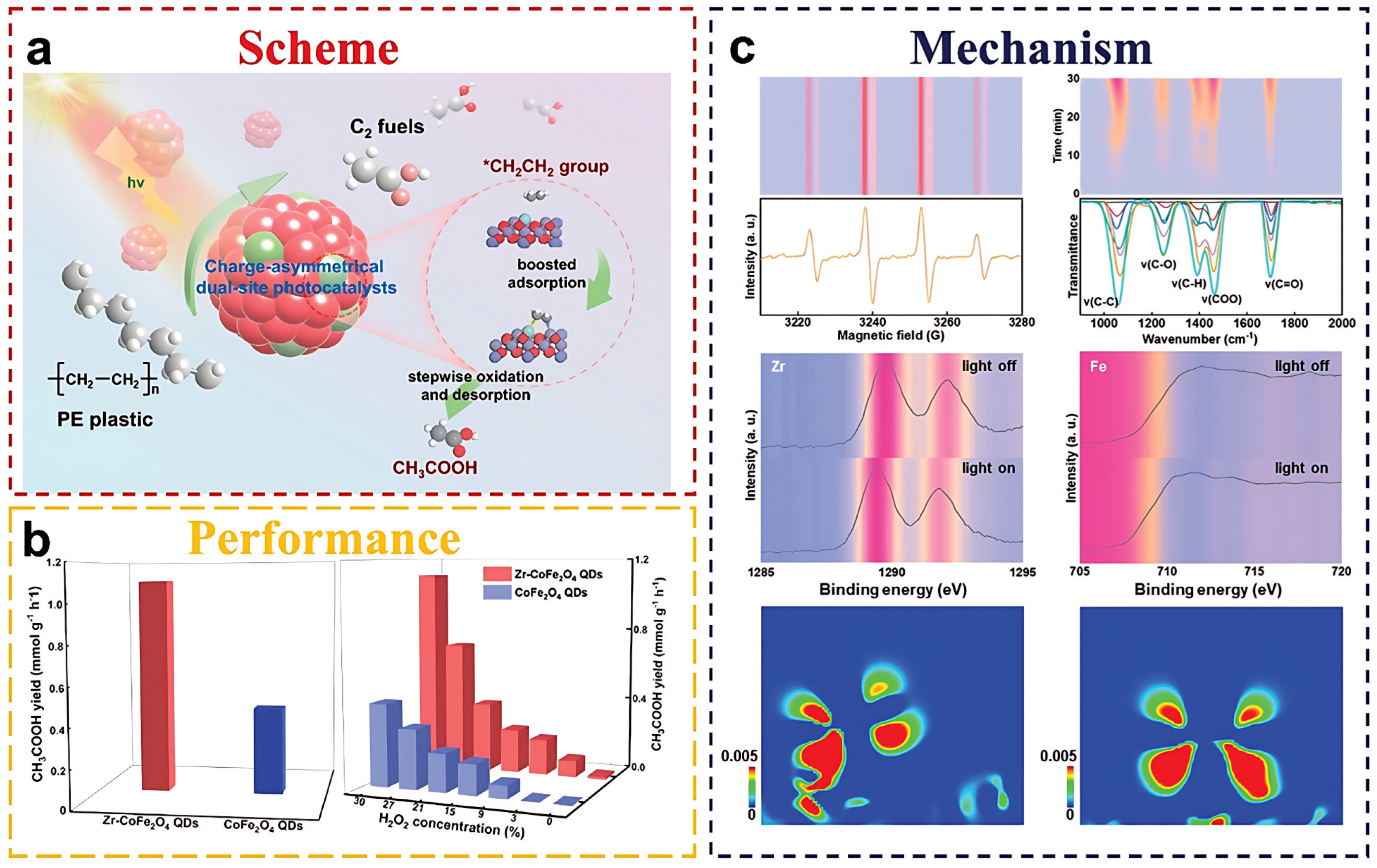

5.3. Polyolefin (PE, PP) Bond Scission and Upcycling

5.4. Polylactic Acid and Other Aliphatic Polyesters

5.5. Toxicity and Environmental Impacts of Plastic Polymers

6. Reactor Engineering and Process Integration for MOF-Catalyzed Plastic Degradation and Upcycling

6.1. Batch Versus Continuous-Flow Configurations

6.2. Fixed-Bed and Membrane Reactors with Immobilized MOFs

6.3. Coupling MOF Catalysis with Enzymatic or Electrochemical Steps

7. System-Level Assessment for MOF-Enabled Plastic Recycling

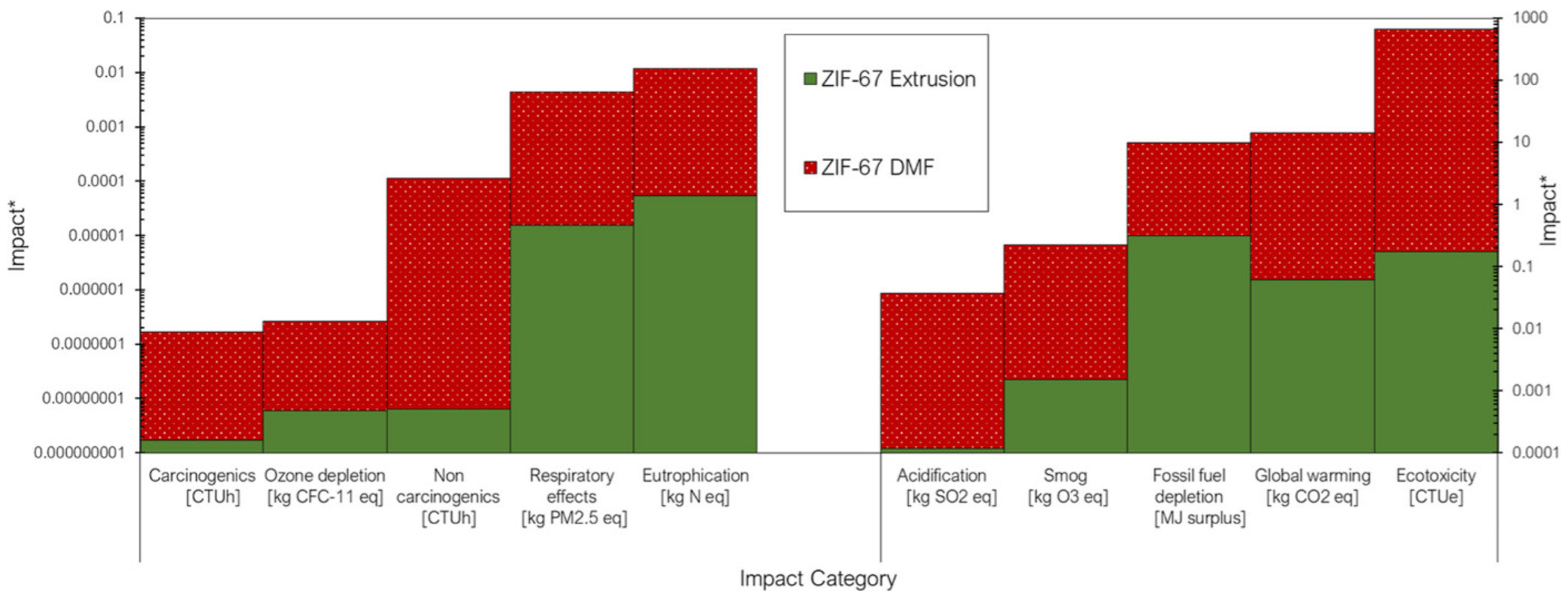

7.1. Life Cycle Assessment and Deployment Metrics

7.2. Techno-Economic Benchmarking of MOF-Enabled Recycling Pathways

7.3. Catalyst Regeneration, Stability, and Leaching Control

8. Challenges and Future Opportunities

8.1. Limitations and Challenges

8.2. Future Opportunities

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOF | Metal–Organic Framework |

| COF | Covalent Organic Framework |

| ZIF | Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework |

| PET | Poly(ethylene terephthalate) |

| BHET | Bis(hydroxyethyl) terephthalate |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PBS | Poly(butylene succinate) |

| PBAT | Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) |

| PCL | Poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| PGA | Polyglycolic Acid |

| PA | Phenylacetylene |

| ST | Styrene |

| TRACI | Tool for the Reduction and Assessment of Chemical and Other Environmental Impacts |

References

- Shah, H.H.; Amin, M.; Iqbal, A.; Nadeem, I.; Kalin, M.; Soomar, A.M.; Galal, A.M. A review on gasification and pyrolysis of waste plastics. Front. Chem. 2023, 10, 960894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Artetxe, M.; Amutio, M.; Alvarez, J.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Recent advances in the gasification of waste plastics. A critical overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jehanno, C.; Alty, J.W.; Roosen, M.; De Meester, S.; Dove, A.P.; Chen, E.Y.-X.; Leibfarth, F.A.; Sardon, H. Critical advances and future opportunities in upcycling commodity polymers. Nature 2022, 603, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-R.; Kuppler, R.J.; Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1477–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Hong, C.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Catalytic depolymerization of polyester plastics toward closed-loop recycling and upcycling. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Guo, M.; Zhang, R.W.; Huang, Q.; Wang, G.; Lan, Y.Q. When microplastics/plastics meet metal-organic frameworks: Turning threats into opportunities. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 17781–17798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Tan, T.T.Y.; Otake, K.I.; Kitagawa, S.; Lim, J.Y.C. MOF Catalysts for Plastic Depolymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202504017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, B.; Wong, S.O.; Duckworth, A.; White, A.J.P.; Hill, M.R.; Ladewig, B.P. Upcycling a plastic cup: One-pot synthesis of lactate containing metal organic frameworks from polylactic acid. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 7319–7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O.M. Reticular Chemistry—Construction, Properties, and Precision Reactions of Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15507–15509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikhar, S.; Kumar, P.; Chakraborty, M. A review on microplastics degradation with MOF: Mechanism and action. Next Nanotechnol. 2024, 5, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.-X.; Qiao, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.-T.; Wang, J.-X. Upcycling plastic wastes into high-performance nano-MOFs by efficient neutral hydrolysis for water adsorption and photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 19452–19461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X. Multifunctional metal–organic frameworks for photocatalysis. Small 2015, 11, 3097–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, W. Metal–organic frameworks for artificial photosynthesis and photocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5982–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huo, P. Plastic Degradation and Conversion by Photocatalysis. In Plastic Degradation and Conversion by Photocatalysis (Volume 2): From Waste to Wealth; American Chemical Society Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Tian, J.; Chen, Q.; Hong, M. Water-stable metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): Rational construction and carbon dioxide capture. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 1570–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.A.; Shaver, M.P. Depolymerization within a Circular Plastics System. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 2617–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropietro, T.F. Metal-organic frameworks and plastic: An emerging synergic partnership. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2023, 24, 2189890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain, M.; Van Passel, S.; Thomassen, G.; Van Gorp, B.; Nhu, T.T.; Huysveld, S.; Van Geem, K.M.; De Meester, S.; Billen, P. Techno-economic assessment of mechanical recycling of challenging post-consumer plastic packaging waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 170, 105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Preez, W.; Mauchline, D.A.; van der Merwe, A.F.; van der Walt, J.; Becker, T.; Modiba, R.; Chauke, H.; Dzogbewu, T.; Mostert, R.; Maringa, M.; et al. Review of the current state-of-the-art in plasma gasification of municipal and medical waste. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 406, 05008. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gui, B.; Wang, W.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Sun, J.; Wang, C. Ultrahigh–surface area covalent organic frameworks for methane adsorption. Science 2024, 386, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hanna, S.L.; Redfern, L.R.; Alezi, D.; Islamoglu, T.; Farha, O.K. Reticular chemistry in the rational synthesis of functional zirconium cluster-based MOFs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 386, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, W.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Hou, H. Synergistic Effects of Lewis Acid-Base Pair Sites—Hf-MOFs with Functional Groups as Distinguished Catalysts for the Cycloaddition of Epoxides with CO2. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 3817–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Kirlikovali, K.O.; Gong, X.; Atilgan, A.; Ma, K.; Schweitzer, N.M.; Gianneschi, N.C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Catalytic Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate Using a Phase-Transitional Zirconium-Based Metal-Organic Framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202117528. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenhaute, S.; Cools-Ceuppens, M.; DeKeyser, S.; Verstraelen, T.; Van Speybroeck, V. Machine learning potentials for metal-organic frameworks using an incremental learning approach. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kang, J.; Cha, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.; Kang, H.; Choi, I.; Kim, M. Stability of Zr-Based UiO-66 Metal-Organic Frameworks in Basic Solutions. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, S.; Fuentes-Fernandez, E.M.A.; Tan, K.; Xu, F.; Li, J.; Chabal, Y.J.; Thonhauser, T. Understanding and controlling water stability of MOF-74. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 5176–5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Qian, S.; Liu, Z.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Depolymerization and re/upcycling of biodegradable PLA plastics. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13509–13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Naskar, S.; Maurin, G. Unconventional mechanical and thermal behaviours of MOF CALF-20. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shen, C.; Yu, G.; Chen, X. Fabrication of magnetic bimetallic Co–Zn based zeolitic imidazolate frameworks composites as catalyst of glycolysis of mixed plastic. Fuel 2021, 304, 121397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Q.; Gu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Dao, X.-Y.; Cheng, X.-M.; Ma, J.; Sun, W.-Y. Defect-engineering of Zr (IV)-based metal-organic frameworks for regulating CO2 photoreduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dong, J.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Moon, H.; Scott, S.L. Catalytic upcycling of polyolefins. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 9457–9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon-Tovar, L.; Carné-Sánchez, A.; Carbonell, C.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D. Optimised room temperature, water-based synthesis of CPO-27-M metal–organic frameworks with high space-time yields. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 20819–20826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, G.C.; Chavan, S.; Bordiga, S.; Svelle, S.; Olsbye, U.; Lillerud, K.P. Defect engineering: Tuning the porosity and composition of the metal–organic framework UiO-66 via modulated synthesis. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 3749–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtch, N.C.; Jasuja, H.; Walton, K.S. Water stability and adsorption in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10575–10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermoortele, F.; Bueken, B.; Le Bars, G.; Van de Voorde, B.; Vandichel, M.; Houthoofd, K.; Vimont, A.; Daturi, M.; Waroquier, M.; Van Speybroeck, V. Synthesis modulation as a tool to increase the catalytic activity of metal–organic frameworks: The unique case of UiO-66 (Zr). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11465–11468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, D.S.; Tsai, D.-H. Recent advances in continuous flow synthesis of metal–organic frameworks and their composites. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 8497–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Mottillo, C.; Titi, H.M. Mechanochemistry for synthesis. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, C.A.; Gagnon, K.J.; Lee, S.; Gándara, F.; Bürgi, H.B.; Yaghi, O.M. Definitive molecular level characterization of defects in UiO-66 crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 11162–11167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; Sardo, M.; Vieira, R.; Marín-Montesinos, I.; Mafra, L. Enhancing CO2 Capture Via Fast Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of the CALF-20 Metal–Organic Framework. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 3302–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.J.; Brown, Z.J.; Colón, Y.J.; Siu, P.W.; Scheidt, K.A.; Snurr, R.Q.; Hupp, J.T.; Farha, O.K. A facile synthesis of UiO-66, UiO-67 and their derivatives. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9449–9451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valizadeh, B.; Nguyen, T.N.; Stylianou, K.C. Shape engineering of metal–organic frameworks. Polyhedron 2018, 145, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottillo, C.; Friščić, T. Advances in solid-state transformations of coordination bonds: From the ball mill to the aging chamber. Molecules 2017, 22, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustini, M.; Kim, J.; Jeong, G.-Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Moon, H.R.; Ahn, W.-S.; Kim, D.-P. Microfluidic approach toward continuous and ultrafast synthesis of metal–organic framework crystals and hetero structures in confined microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14619–14626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntouros, V.; Kousis, I.; Pisello, A.L.; Assimakopoulos, M.N. Binding materials for MOF monolith shaping processes: A review towards real life application. Energies 2022, 15, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.M. Postsynthetic methods for the functionalization of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 970–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cohen, S.M. Postsynthetic modification of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorignon, F.; Gossard, A.; Carboni, M. Hierarchically porous monolithic MOFs: An ongoing challenge for industrial-scale effluent treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, A.W.; Babarao, R.; Jain, A.; Trousselet, F.; Coudert, F.-X. Defects in metal–organic frameworks: A compromise between adsorption and stability? Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 4352–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, X.-Q.; Jiang, H.-L.; Sun, L.-B. Metal–organic frameworks for heterogeneous basic catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8129–8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wied, P.; Carraro, F.; Sumby, C.J.; Nidetzky, B.; Tsung, C.K.; Falcaro, P.; Doonan, C.J. Metal-Organic Framework-Based Enzyme Biocomposites. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1077–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Chen, R.; Hui, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhao, C.X. Boosting Enzyme Activity in Enzyme Metal-Organic Framework Composites. Chem. Bio Eng. 2024, 1, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelalak, R.; Thi, T.T.; Golestanifar, F.; Aallaei, M.; Heidari, Z. Molecular dynamics insights into the adsorption mechanism of acidic gases over iron based metal organic frameworks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C.; Pérez-Madrigal, M.M.; Demarteau, J.; Sardon, H.; Dove, A.P. Organocatalysis for depolymerisation. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khopade, K.V.; Chikkali, S.H.; Barsu, N. Metal-catalyzed plastic depolymerization. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, A.-C.; Grecu, I.; Samoila, P. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) recycled by catalytic glycolysis: A bridge toward circular economy principles. Materials 2024, 17, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, S.; Fisse, J.; Vogt, D. Optimization and kinetic evaluation for glycolytic depolymerization of post-consumer PET waste with sodium methoxide. Polymers 2023, 15, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y. Current Advances in Biodegradation of Polyolefins. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elora, A.A.; Sarker, T.; Tahmid, I.; Paul, P.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Saha, B.B.; Sarker, M. Highly efficient MnOX/TiO2@ NH2-ZIF-8 composite for the removal of toxic textile dyes from water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 718, 136882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracida-Alvarez, U.R.; Xu, H.; Benavides, P.T.; Wang, M.; Hawkins, T.R. Circular Economy Sustainability Analysis Framework for Plastics: Application for Poly(ethylene Terephthalate) (PET). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Q.; Zi, J.; Bai, Z.; Qi, S. The glycolysis of poly (ethylene terephthalate) promoted by metal organic framework (MOF) catalysts. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Jo, J.H.; An, E.J.; Lee, G.; Chi, W.S.; Lee, C. Dual-porous ZIF-8 heterogeneous catalysts with increased reaction sites for efficient PET glycolysis. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-X.; Bieh, Y.-T.; Chen, C.H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Kato, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Tsung, C.-K.; Wu, K.C.-W. Heterogeneous metal azolate framework-6 (MAF-6) catalysts with high zinc density for enhanced polyethylene terephthalate (PET) conversion. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 6541–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, T.; Yu, G.; Chen, X. A new class of catalysts for the glycolysis of PET: Deep eutectic solvent@ ZIF-8 composite. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 183, 109463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Shao, Z.; Gao, F.; Gao, K.; Teng, C.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, P.; Song, G. Efficient alcoholysis of waste rigid polyurethane foam using MIL-101 (Fe) catalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 366, 132764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, C.; Sangwan, P.; Yu, L.; Tong, Z. Accelerating the degradation of polyolefins through additives and blending. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, M.; Thadhani, C.; Rana, B.; Gupta, P.; Ghosh, B.; Manna, K. Hydrogenolysis of Polyethylene by Metal–Organic Framework Confined Single-Site Ruthenium Catalysts. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 10670–10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Huang, W. Chemical upcycling of polyolefin plastics using structurally well-defined catalysts. JACS Au 2024, 4, 2081–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilias, D.S. Waste Material Recycling in the Circular Economy: Challenges and Developments; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sintim, H.Y.; Bary, A.I.; Hayes, D.G.; English, M.E.; Schaeffer, S.M.; Miles, C.A.; Zelenyuk, A.; Suski, K.; Flury, M. Release of micro-and nanoparticles from biodegradable plastic during in situ composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 675, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Huo, Y.; Wang, X.; Huo, M. Optimizing Polylactic Acid Alcoholysis Efficiency with POM@ MOF Catalysis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 721, 137192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, T.P.; Völker, C.; Kramm, J.; Landfester, K.; Wurm, F.R. Plastics of the future? The impact of biodegradable polymers on the environment and on society. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithner, D.; Larsson, Å.; Dave, G. Environmental and health hazard ranking and assessment of plastic polymers based on chemical composition. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3309–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Powell, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, P. Microplastics as contaminants in the soil environment: A mini-review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayanleye, S.O. Development of Preservative-Treated Cross-Laminated Timber and Lignin-Reinforced Polyurethane-Adhesive for Glued Laminated Timber. Ph.D. Thesis, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bócoli, P.F.J.; Gomes, V.E.d.S.; Maia, A.A.D.; Marangoni Júnior, L. Perspectives on Eco-Friendly Food Packaging: Challenges, Solutions, and Trends. Foods 2025, 14, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, M.; Châtel, A.; Mouneyrac, C. Micro (nano) plastics: A threat to human health? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadian, S.M.; Onay, T.T.; Demirel, B. Biodegradation of bioplastics in natural environments. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Duque, J.; Galindo, A.S.; Herrera, R.R. Biodegradable Polymers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Dyosiba, X.; Musyoka, N.M.; Langmi, H.W.; Mathe, M.; Liao, S. Review on the current practices and efforts towards pilot-scale production of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 352, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagi, S.; Yuan, S.; Rojas-Buzo, S.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Román-Leshkov, Y. A continuous flow chemistry approach for the ultrafast and low-cost synthesis of MOF-808. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 9982–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinstry, C.; Cathcart, R.J.; Cussen, E.J.; Fletcher, A.J.; Patwardhan, S.V.; Sefcik, J. Scalable continuous solvothermal synthesis of metal organic framework (MOF-5) crystals. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 285, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Malik, F.; Min Hein, Z.; Huang, J.; You, H.; Zhu, Y. Continuous Flow Synthesis and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks: Advances and Innovations. ChemPlusChem 2025, 90, e202400634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakuru, V.R.; Fazl-Ur-Rahman, K.; Periyasamy, G.; Velaga, B.; Peela, N.R.; DMello, M.E.; Kanakikodi, K.S.; Maradur, S.P.; Maji, T.K.; Kalidindi, S.B. Unraveling high alkene selectivity at full conversion in alkyne hydrogenation over Ni under continuous flow conditions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 5265–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, A.; Kanakikodi, K.S.; Bakuru, V.R.; Kulkarni, B.B.; Maradur, S.P.; Kalidindi, S.B. Continuous Flow Liquid-Phase Semihydrogenation of Phenylacetylene over Pd Nanoparticles Supported on UiO-66 (Hf) Metal-Organic Framework. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202203926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cai, P.; Elumalai, P.; Zhang, P.; Feng, L.; Al-Rawashdeh, M.m.; Madrahimov, S.T.; Zhou, H.-C. Site-isolated azobenzene-containing metal–organic framework for cyclopalladated catalyzed suzuki-miyuara coupling in flow. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 51849–51854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, J.E.; Roach, M.C.; Reynolds, M.M. Continuous flow catalysis with CuBTC improves reaction time for synthesis of xanthene derivatives. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1259835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.; Boyall, S.L.; Müller, P.; Harrington, J.P.; Sobolewska, A.M.; Reynolds, W.R.; Bourne, R.A.; Wu, K.; Collins, S.M.; Muldowney, M. MOF-based heterogeneous catalysis in continuous flow via incorporation onto polymer-based spherical activated carbon supports. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 17910–17921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yang, C.; Xu, F.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X. Metal organic frameworks as solid catalyst for flow acetalization of benzaldehyde. Microchem. J. 2021, 165, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Chen, Y. Dynamic exchange strategy for enzyme immobilization in Zr-based metal-organic frameworks for green synthesis of β-lactam antibiotics. Green Chem. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.D.; Gargate, N.; Tiwari, M.S.; Nadar, S.S. Defect metal-organic frameworks (D-MOFs): An engineered nanomaterial for enzyme immobilization. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 531, 216519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Cao, N.; Yang, W. Metal-organic framework membranes and membrane reactors: Versatile separations and intensified processes. Research 2020, 2020, 1583451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lee, L.Y.S. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrocatalysis: Catalyst or Precatalyst? ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanati, S.; Morsali, A.; Garcia, H. Metal-organic framework-based materials as key components in electrocatalytic oxidation and reduction reactions. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 87, 540–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.D.; Beiler, A.M.; Johnson, B.A.; Liseev, T.; Castner, A.T.; Ott, S. Analysis of electrocatalytic metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 406, 213137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Hernandez, H.U.; Quan, Y.; Papadaki, M.I.; Wang, Q. Life cycle assessment of metal–organic frameworks: Sustainability study of zeolitic imidazolate framework-67. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 4219–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, C.A.; Blom, R.; Spjelkavik, A.; Moreau, V.; Payet, J. Life-cycle assessment as a tool for eco-design of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2017, 14, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rorrer, N.A.; Nicholson, S.R.; Erickson, E.; DesVeaux, J.S.; Avelino, A.F.; Lamers, P.; Bhatt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Avery, G. Techno-economic, life-cycle, and socioeconomic impact analysis of enzymatic recycling of poly (ethylene terephthalate). Joule 2021, 5, 2479–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Ke, F.-S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, W.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y. Facile and reversible digestion and regeneration of zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zou, C. The impact of metal leaching in MOF materials on the evaluation of photocatalytic CO2 reduction activity—A case study. Next Energy 2025, 7, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Gates, B.C. Catalysis by metal organic frameworks: Perspective and suggestions for future research. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 1779–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waribam, P.; Katugampalage, T.R.; Opaprakasit, P.; Ratanatawanate, C.; Chooaksorn, W.; Wang, L.P.; Liu, C.-H.; Sreearunothai, P. Upcycling plastic waste: Rapid aqueous depolymerization of PET and simultaneous growth of highly defective UiO-66 metal-organic framework with enhanced CO2 capture via one-pot synthesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Kong, D.; Xiong, F.; Qiu, T.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, Y.; Qin, M.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. Enhancing hydrophobicity via core–shell metal organic frameworks for high-humidity flue gas CO2 capture. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 61, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Jun, B.-M.; Jang, M.; Park, C.M.; Muñoz-Senmache, J.C.; Hernández-Maldonado, A.J.; Heyden, A.; Yu, M.; Yoon, Y. Removal of contaminants of emerging concern by metal-organic framework nanoadsorbents: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 928–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canivet, J.; Fateeva, A.; Guo, Y.; Coasne, B.; Farrusseng, D. Water adsorption in MOFs: Fundamentals and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5594–5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Férey, G.; Serre, C.; Devic, T.; Maurin, G.; Jobic, H.; Llewellyn, P.L.; De Weireld, G.; Vimont, A.; Daturi, M.; Chang, J.-S. Why hybrid porous solids capture greenhouse gases? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Xu, Y.; Wei, G. Recent Advances in Biomolecule-Engineered Metal-Organic Frameworks (Bio-MOFs): From Design, Bioengineering, and Structural/functional Regulation to Biocatalytic Applications. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202500001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Deibert, B.J.; Li, J. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks for chemical sensing and explosive detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5815–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Diercks, C.S.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Kornienko, N.; Nichols, E.M.; Zhao, Y.; Paris, A.R.; Kim, D.; Yang, P.; Yaghi, O.M. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water. Science 2015, 349, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.L.; Xu, Q. Metal–organic frameworks as platforms for catalytic applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1703663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peters, A.W.; Bernales, V.; Ortuno, M.A.; Schweitzer, N.M.; DeStefano, M.R.; Gallington, L.C.; Platero-Prats, A.E.; Chapman, K.W.; Cramer, C.J. Metal–organic framework supported cobalt catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane at low temperature. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösler, C.; Fischer, R.A. Metal–organic frameworks as hosts for nanoparticles. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissegna, S.; Epp, K.; Heinz, W.R.; Kieslich, G.; Fischer, R.A. Defective metal-organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Bueken, B.; De Vos, D.E.; Fischer, R.A. Defect-engineered metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7234–7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wei, Z.; Gu, Z.-Y.; Liu, T.-F.; Park, J.; Park, J.; Tian, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Gentle III, T. Tuning the structure and function of metal–organic frameworks via linker design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5561–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Fu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ye, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Fu, X.; Li, Z. Studies on photocatalytic CO2 reduction over NH2-Uio-66 (Zr) and its derivatives: Towards a better understanding of photocatalysis on metal–organic frameworks. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14279–14285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C. Synthesis, Characterization, and Shaping of UiO-67 Metal-Organic Frameworks. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, New Zealand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Tec-Caamal, E.N.; Natarajan, A.; Thanh, N.C. New strategies and advancements in the synthesis of metal organic frameworks for PAHs removal. iScience 2025, 28, 112561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.M.; Kim, D.; Rungtaweevoranit, B.; Trickett, C.A.; Barmanbek, J.T.D.; Alshammari, A.S.; Yang, P.; Yaghi, O.M. Plasmon-enhanced photocatalytic CO2 conversion within metal–organic frameworks under visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Hanna, S.L.; Wang, X.; Taheri-Ledari, R.; Maleki, A.; Li, P.; Farha, O.K. A historical overview of the activation and porosity of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7406–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.-C.; Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: Synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12278–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julien, P.A.; Mottillo, C.; Friščić, T. Metal–organic frameworks meet scalable and sustainable synthesis. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2729–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Martinez, M.; Avci-Camur, C.; Thornton, A.W.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D.; Hill, M.R. New synthetic routes towards MOF production at scale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3453–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-C.; Long, J.R.; Yaghi, O.M. Introduction to metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 673–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.M. Modifying MOFs: New chemistry, new materials. Chem. Sci. 2010, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D.; Coudert, F.-X. Predicting the mechanical properties of zeolite frameworks by machine learning. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7833–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, W.; Khoiruddin, K.; Wenten, I.G.; Kawi, S. Advancing Carbon Capture with Bio-Inspired Membrane Materials: A review. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification (Bond-Breaking Modality) | Representative MOF Types/Metals | Key Function | Target Polymers | Distinctive Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolytic/Alcoholytic/Aminolytic | Zr- or Hf-carboxylates (e.g., UiO-66 series) | Coordinate and activate ester/amide linkages | Polyesters (PET), Polyamides (Nylon) | Mild conditions; enables recov ery of pure monomers | [7,13,25] |

| Redox/Photocatalytic | Fe, Ti frameworks, linker-based chromophores, MOF–semiconductor hybrids | Generate ROS for C–O and C–C bond scission | PET, PLA | Light-driven, tunable selectivity; requires engineered stability and oxygen/light delivery | [14,15,16] |

| MOF-derived catalysts | Pyrolyzed M–N–C motifs, Ru/Ni hydride ensembles | Tandem cracking, hydrogenolysis, isomerization | Polyolefins (PE, PP) | Effective for otherwise inert backbones; integrates metal nanoparticle activity | [33] |

| Adsorptive preconcentration | MOF/COF membranes, defect-rich frameworks | Capture and concentrate oligomers prior to catalytic cleavage | Mixed waste streams | “Adsorb-to-deconstruct-to-upcycle” workflow; enhances mass transport efficiency | [10,18,19] |

| MOF | PET/Catalyst (w/w) | BHET (%) | PET Conversion (%) | Ethylene Glycol/PET (w/w) | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Pressure (atm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAF-6 | 100/1 | 81.7 | 92.4 | 6/1 | 180 | 4 | 1 | [64] |

| MAF-5 | 100/1 | 39 | 72.3 | 6/1 | 180 | 4 | 1 | |

| MAF-32 | 100/1 | 38.2 | 52.6 | 6/1 | 180 | 4 | 1 | |

| ZIF-8 | 100/1 | 73.6 | 100 | 5/1 | 190 | 1 | – | [31] |

| ZIF-67 | 100/1 | 79.5 | 100 | 5/1 | 190 | 1 | – | |

| ZIF-8/ZIF-67 | 100/1 | 83.4 | 100 | 5/1 | 190 | 1 | – | |

| ZIF-8 | 25/1 | 72.6 | 100 | 5/1 | 195 | 0.5 | 0.99 | [65] |

| DES@ | 25/1 | 83.2 | 100 | 5/1 | 195 | 0.42 | 0.99 | |

| ZIF-8 | ||||||||

| ZIF-8 | 100/1 | 76.75 | 100 | 5/1 | 197 | 1.5 | 1 | [62] |

| ZIF-67 | 100/1 | 76 | 100 | 5/1 | 197 | 2.5 | 1 | |

| MOF-5 | 100/1 | 73 | 100 | 5/1 | 197 | 3.5 | 1 | |

| ZIF-8 | 100/1 | 65.9 | 88.2 | 5/1 | 180 | 4 | 1 | [63] |

| DPZIF-8 | 100/1 | 76.1 | 91.7 | 5/1 | 180 | 4 | 1 |

| Catalyst | Reactor Type | Reaction Type | Activity | Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni@C-300R | fixed-bed continuous down-flow quartz reactor | Semi-hydrogenation of phenylacetylene to styrene | 99.3 % PA conversion and 92.0 % ST selectivity[a] | stable for 5 h | [86] |

| Pd/UiO-66(Hf) | liquid-phase continuous down-flow quartz reactor | Semi-hydrogenation of phenylacetylene to styrene | 99 % PA conversion and 90 % ST selectivity[a] | Reused 4 times | [87] |

| PCN-160-Pd | microflow | Suzuki–Miyaura coupling | TON of 18 for 12 h | NA | [88] |

| CuBTC[b] | stainless-steel column packed | Intramolecular condensation reaction for the synthesis of xanthene derivatives | yield of 33 % ± 14 % | NA | [89] |

| MIL-100(Sc)@PBSAC[c] | packed-bed reactors | Intramolecular cyclization of (±)-citronellal | Selectivity to 88.8 ± 6.5 | NA | [90] |

| MIL-100(Fe) | microreactor | Acetalization of aldehyde | Conversion over 90 % for more than 96 h | NA | [91] |

| Polymer | MOF Catalyst | Reaction Conditions | STY (kg·m−3·day−1) | Selectivity (%) | Product Purity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | UiO-66-NH2 | 180 °C, EG solvent, 24 h | ~0.45 | 85 | 92 (BHET) | [64,65,104] |

| PET | MOF-808 | 150 °C, aqueous, 12 h | 0.32 | 78 | 88 (TPA) | [64,65,104] |

| PU | Zn-MOF | 120 °C, methanol, 10 h | 0.20 | 70 | - | [62,66] |

| PE/PP | MIL-101(Fe) | Photocatalysis, 300 W Xe lamp | - | 65 | 80 (oxidized frag) | [69,70,71] |

| PLA | Zr-MOF (MIP-202) | Hydrolytic, 90 °C, water | 0.15 | 82 | 95 (lactic acid) | [29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, K.; Han, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.-s.; Park, J.-A.; Lim, K.S.; Ha, S.-J.; Kim, H.-O. Metal–Organic Framework for Plastic Depolymerization and Upcycling. Crystals 2025, 15, 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100897

Lee K, Han S, Kim M, Kim B-s, Park J-A, Lim KS, Ha S-J, Kim H-O. Metal–Organic Framework for Plastic Depolymerization and Upcycling. Crystals. 2025; 15(10):897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100897

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Kisung, Sumin Han, Minse Kim, Byoung-su Kim, Jeong-Ann Park, Kwang Suk Lim, Suk-Jin Ha, and Hyun-Ouk Kim. 2025. "Metal–Organic Framework for Plastic Depolymerization and Upcycling" Crystals 15, no. 10: 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100897

APA StyleLee, K., Han, S., Kim, M., Kim, B.-s., Park, J.-A., Lim, K. S., Ha, S.-J., & Kim, H.-O. (2025). Metal–Organic Framework for Plastic Depolymerization and Upcycling. Crystals, 15(10), 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100897