Abstract

Prompted by a real-life observation in the UK retail market, a two-player Prisoners’ Dilemma model of an alliance between two firms is adapted to include the response of a rival firm, resulting in a version of a three-player Prisoners’ Dilemma. We use this to analyse the impact on the stability of the alliance of the rival’s competition, either with the alliance or with the individual partners. We show that, while strong external pressure on both partners can cause Ally-Ally to become a Nash equilibrium for the two-player Prisoners’ Dilemma, weak or asymmetric pressure that plays on the partners’ differing objectives can undermine the alliance. As well as providing new insights into how allies should respond if the alliance is to continue, this also illustrates how a third party can most effectively cause the alliance to become unsustainable. We create a new game theoretic framework, adding value to existing theory and the practice of alliance formation and sustainability.

1. Introduction

While many aspects of business alliances have been modeled in the literature, the focus of academic research is the motives of, and relations between, the partners, and almost nothing is said about the impact of external changes or the reaction of third parties. We address this gap by giving an account of an alliance that failed partly, as it seems to us, because the erstwhile allies were measuring the success of the alliance in terms of regaining market share previously lost to a powerful competitor. The initial outcome of the alliance lay in the “gray area” identified by [1](p. 1058), where each partner is satisfied with the overall alliance, but neither considered it an extreme success or an extreme failure. We offer a simple formal model of this situation, which suggests that, while the allies were right to be concerned about the reaction of this third party, there was insufficient understanding of how this might create stresses within the alliance. Indeed, a determined third party seeking to break up an alliance should attack the parties asymmetrically; an undifferentiated attack on the alliance as a whole could have the effect of strengthening it. It also emerges from this model that such stresses can also be caused by asymmetries in the environment in which the alliance operates if, for example, regulatory changes are problematic for one partner, but not the other. We also suggest that unilateral commitments may make alliances more robust in some cases, but not in others, questioning what appears to be the consensus in the literature that “Mutual cooperation in the alliance (i.e., where partners invest high-quality resources—human, tangible and intangible) generates high net pay-offs to each firm” [1].

2. Analysis of a Real-Life Scenario: Boots and Sainsbury’s in the Years 2001–2003

There have been reports for many years of alliances between competitors with the promise of improved market performance, due to eliminating rivalry hazards. Our investigation was prompted by a newspaper report by [2] that an alliance with exactly these aims had been formed between Boots, the United Kingdom’s leading health and beauty retailer and provider of pharmacy services, and Sainsbury’s, a leading UK food retailer with interests in financial services.

2.1. Setting up the Alliance

The parties notified UK competition authorities of their intentions in the following terms:

The parties propose to enter into arrangements under which Sainsbury’s will withdraw from the retailing of health and beauty products in certain of its edge-of-town and out-of-town stores and instead license Boots to retail its own health and beauty products from within the main body of the Sainsbury’s store (from [3])

From our position as collaborators with one of the partners,1 it appeared to us that, in the typology of [4], this was intended to be a business alliance focussed on exploitation of partners’ assets to improve market positioning by, in the words of [5], the creation of synergistic and competitive advantages. In the words of the managing director of Boots the Chemist:

The attraction of the Sainsbury’s programme for us is that it allows us to gain some of the footfall in edge-of-town shopping that we are missing out on [6].We want to have 200 outlets on the edge of town, and Sainsbury’s is the way we might do this [7].

Sainsbury’s was also making similar alliances with other retail brands [8,9]; Sara Weller, then Assistant Managing Director of Sainsbury’s, explained the strategy to the company’s shareholders:

We are testing that by putting our brand and Boots together in one location, the customers will find that a more appealing offer than anything we can do singly ourselves (from [10]).

Then, it would not have been surprising when, less than two years later2, it was reported that:

Boots and Sainsbury’s are ending their health and beauty joint venture after a row over how to divide up the revenues from the chemist stores within the supermarket chain [12].

The partners appear not to have been satisfied that the expected value produced by their collaboration was proportional to their contributions; what [13] (p. 1055) refer to as “distributive fairness.”

2.2. External Pressure on the Alliance

It seemed to us that there was, in effect, a third party to this alliance, namely Tesco. It is part of British folklore that Sainsbury’s was for decades the premier supermarket in the UK, losing this position in 1995 to Tesco, further slipping to third place in 2003 behind Walmart-owned Asda [14]. Contemporary academic accounts of some of these interactions can be found in [15,16,17], and they explain the significance of Boots to UK consumers and offer another, complementary, perspective to our analysis.

The relationships between Boots and Sainsbury’s is in some respects similar to that of the non-dominant firms, with Tesco as the “dominant” firm in [18]. Certainly, throughout the period of their collaboration, much media and other comment about Boots and Sainsbury’s focussed on the companies’ performance in relation to Tesco, or the impact on them of Tesco’s strategies:

Boots has been under attack from supermarkets for some time. Tesco and Asda have been eating into its core market with aggressive price cuts on toiletries.But it has fought back with more product promotions and new initiatives such as dentistry, leisure centres and nail bars. Sainsbury’s is also coming from behind, trying to catch rivals Tesco and Asda, which have a greater non-food focus [19].

While British rivals such as Sainsbury’s and Safeway try to improve profitability, Tesco is deliberately keeping its margins flat, ploughing back into lower prices the gains it reaps from economies of scale. That brings more sales, and so more scale economies. …Similarly, the group has moved aggressively into over-the-counter medicines and toiletries. This year, its sales overtook those of Boots, Britain’s leading chemists chain [20].

Sainsbury’s acknowledged the primacy of Tesco as a competitor in its evidence on the company’s competition price monitoring to the Competition Commission enquiry into UK supermarkets:

Sainsbury’s tracks 2000 product lines every four weeks. Monitors Tesco most … ([21] (Appendix 7.4)).

It seems inevitable that the two companies saw regaining some of the ground they had lost to Tesco as a valuable payoff of this alliance and that they considered Tesco’s likely response in the planning process, but the outcome appears to indicate that they did not go on to analyse the pressures that this might put on their cooperation.

2.3. Bargaining Power of the Partners

It will be important later on in our discussion that the situation of Boots and Sainsbury’s differed significantly. To begin with, Boots was facing increasing competition from the main UK supermarkets, particularly following a court ruling in May 2001, which ended Resale Price Maintenance on over-the-counter medicines in the UK, threatening a significant reduction in the company’s profits. Furthermore, possible changes in the regulatory environment [22] (see also [23]) could have undermined the market position of one of the partners and strengthened that of the other. Throughout the period of our observation, there was public concern about the encroachment of supermarket chains into the provision of pharmacy services and a corresponding political debate about the control of entry in which Boots and Sainsbury’s were on opposing sides. Furthermore, Tesco and Sainsbury’s had been competing for decades in the grocery business, from which had emerged accommodations of various kinds, such as “the situation in which the majority of their products were not fully exposed to competitive pressure”[21] and the “truce” noted here:

The price battle which formed a large part of the private label war has ended in something of a truce between Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Asda. While competition remains fierce, there has been a palpable shift in strategy from cheap and cheerful private label to private label ranges that offer consumer lifestyle solutions, particularly among the top two grocers: Tesco and Sainsbury’s [24].

Tesco’s competition with Boots is part of a much more recent strategy to become “as strong in non-food as food” [25] and has brought Tesco into entirely new areas of the retail marketplace with aggressive price competition on a very wide front [26].

The following section reviews the existing literature on alliances insofar as it bears upon our main contribution, namely a three-player Prisoners’ Dilemma model and the insights it provides.

3. Literature Review on Business Alliances

As readers are probably aware, hundreds of scholars have written thousands of papers over the years analysing the success factors and reasons for failure of business alliances. Gulati (1998) [27] draws out “five key issues for the study of alliances”: (1) the formation of alliances; (2) the choice of governance structure; (3) the dynamic evolution of alliances; (4) the performance of alliances; (5) the performance consequences for firms entering alliances.

We shall not attempt to review the wealth of theory and comment leading up to and following from Gulati’s detailed analysis nor to identify those studies that provide the greatest insight into the tale we told in the previous section. Instead, we intend to focus on just one issue, which appears to us to be significant, but under-reported in the literature, namely the influence on alliances of competition from third parties. Gulati (1998) [27] observes that “The role of the external environment is usually encapsulated within measures of competitiveness in product or supplier markets” whereas we intend to model a key element of the external environment, namely the strategy adopted by the major rival firm and the impact on items 3 and 4 in this list. The focus of academic research is the motives of, and relations between, the partners:

and shows [29] that business alliances have high failure rates (at or higher than 50%), for non-opportunistic reasons, such as managerial complexity and coordinating costs, but also inter-firm rivalry, as each partner acts to maximize its own benefits.Alliance conditions are composed of collective strengths, inter-partner conflicts, and interdependencies [28].

We address the second reason, taking our cue from [30]:

Later, the same author notes that:This chapter proposes a way to think about the interaction between alliances and competition. It begins by reviewing what the literature in industrial organization has had to say about this question. The short answer is “not much”…

Our study lies in the centre ground of his diagram on p. 45 in [30], and we believe that our simple game-theoretic model sheds light on the viability of an alliance in the presence of a powerful third party. The alliance did not survive long enough for the more sophisticated aspects presented by [30] to emerge, except that it foundered on disagreement about what is referred to there (p. 48) as “Appropriation of Value by Members”, supporting the importance of this aspect of alliances. From a somewhat different standpoint, our analysis of this short-lived alliance supports Propositions 2 and 9 in [31] which analyses the long-established Renault-Nissan alliance.… studies show that there is an intimate link between the balance of cooperation and competition …

The partners were emphatic that a merger was not their aim [32], though other commentators were less categorical [33]. We shall proceed on the basis that the alliance fell within the area studied by [34] in that it involved:

Additionally, it addresses some similar questions (for example, the effect of outside changes), but in a quite different context. Although there is some congruence between expressed findings, they depend on congruent interpretations of terms, which might not be justifiable. For example, we might agree that “The very process of designing and maintaining a collaborative relationship to suit a particular context limits the effectiveness of the collaboration in a changed environment” (p. 174 in [34]), but would we mean the same thing? There is no model or analytical framework in [34] to enable this question to be addressed. Regarding what they describe as “the widely stated but little tested argument that inter-firm collaboration is usually beneficial”, the partners in our study reported positive effects in the collaboration. In particular, it significantly improved Boots’s market share and almost certainly exceeded their expectations; by the end of the trial, the nine implants in Sainsbury’s stores provided around of Boots’s sales [35], so they were performing very well in comparison to the group’s 1400 conventional outlets. Our model supports [34] in finding that a change in one partner’s strategy could well have precipitated the breakdown of the alliance, although no commentator at the time saw this as the cause.[a] cooperative agreement between legally separable organisations that [did] not involve establishing [a]separate organisation.

Although the paper by [36] is concerned with a joint venture and not directly relevant here, we will consider manoeuvres similar in intent and form to these authors’ observation that:

However, as we shall explain, this did not succeed. Rather differently from these authors, we did not identify any feedback loops, so the relationship deteriorated quickly and the alliance was correspondingly short-lived.the partners’ assessments cause[d] them to either engage in renegotiation of the terms of the contract, or to modify their behavior unilaterally, in an attempt to restore balance to the relationship.

The hints at the Prisoners’ Dilemma as a model of some aspects of the interaction between cooperative and opportunistic behaviour in an alliance go back at least as far as Arend and Seale [1], Gulati et al. [37], Parkhe [38]. The last authors give a detailed formal justification that the payoffs for alliance partners do indeed correspond to those in the textbook versions of the game proposed by ([1] (pp. 1059–1061)) and follow this up with formal algebraic deductions. While we adopt a similarly rigorous and algebraic philosophy, we do not need to rely on these authors’ general justification for the use of the Prisoners’ Dilemma as in our model of the Boots-Sainsbury’s alliance; the partner payoffs we identify satisfy the necessary inequalities.

Analysis of the single interaction Prisoners’ Dilemma leads to the conclusion that cooperative behaviour cannot be rational; nevertheless, it is observed by many empirical studies. Charness et al. [39] remark that there is an interesting account of the emergence of cooperation in Prisoners’ Dilemma experiments when the players agree beforehand to change their payoffs; the authors do not appear to have noticed that the same outcome might result were a third party to change the payoffs. The authors of ([37] show that engaging in unilateral commitments significantly increases an alliance’s success rate. There, it is argued that unilateral commitments change the payoff structure of the game in such a way that mutual defection is no longer the Nash equilibrium in the single interaction game. Again, the possible role of third parties is not examined, and the lack of general game theoretic description leaves unexplained why some unilateral commitments lead to an alliance in one situation, but not in others.

4. Our Contribution

In this paper, we seek to overcome some of the lacunae noted in Section 3 by embedding the standard Prisoners’ Dilemma in a three-player game. This allows us to consider not only the nature of the relationship between the allied organisations, but also the changing external conditions within which the alliance operates. Following from our starting point in Section 2, we principally have in mind an omnipresent rational third player who interacts with the first and the second players or the alliance as a whole intentionally, and to a degree, he can choose. The model also sheds light on the impact that an irrational third player, such as “Nature” [40], or a regulatory regime imposed by a government can have on the game. For the most part, we examine the interactions between the allied organisations, treating the third player’s decisions as exogenous; we will consider the best response function of the third player elsewhere. The work of [41] shows that the intervention of a payoff-maximising third party can either reinforce or disrupt an existing alliance.

Our analysis is novel and creates a new framework for using the Prisoner’s Dilemma as a strategic analysis tool, adding a new dimension by explicitly modelling the effect of a third player exerting pressure and thereby modifying the payoffs gained by the first two players. However, we do not follow the classical path in three-player Prisoners’ Dilemma in ([42](p. 79ff) or that of de Ridder and Rusinowska [43], which emphasises the importance of process in alliance formation when more than two players are involved. In the situation that prompted the writing of this paper, competition legislation would have prohibited a Tesco-Sainsbury’s coalition, so evaluation of all possible coalitions is not relevant.

We begin by building in Section 5 a primitive model of player interaction. Guided both by the comments of market analysts about the objective of one of the partners [44]:

and the express intention of the partners [45]:The deal marks an escalation of the supermarket wars as Sainsbury’s desperately tries to recover ground lost to Tesco and Asda,

We have made the key variable for this model customer footfall in the trial stores. Competition in this market is for footfall (see p. 74 in [46]) on the importance of footfall in the health and beauty retail sector); so is where the impact of third parties is felt.The attraction of the Sainsbury’s programme for us is that it allows us to gain some of the footfall in edge-of-town shopping that we are missing out on.

This model correlates well with the empirical studies showing that by considering the two players not in isolation, but in the context of their interaction with the third player, a cooperative Nash equilibrium between the first two players may emerge. We investigate the effect that the behavior of the third player has on the possibility of cooperation. This shows how regulatory mechanisms can control or manage the formation, or not, of alliances by changing the external conditions. Considering the third player as another company attacking the alliance, we show how the basis on which the allies establish their alliance has an effect on its sustainability.

On a more theoretical point, we note that the formation of the grand coalition in this case would contravene UK Office of Fair Trading Regulations. The work of Chatterjee et al. [47] shows that there are significant inefficiencies within this situation, but we have not sought to identify these.

5. Modelling with Prisoners’ Dilemma

In this section, we argue that the interactions in Section 2 can be modeled as a Prisoners’ Dilemma; we will, of course, make some simplifying assumptions and not represent every nuance of the situation. We begin by noting that each partner had an alternative strategy in creating an alliance. Each could be implemented without the involvement of, and sought to gain an advantage at the expense of, the other partner.

A newspaper report at the time the alliance collapsed stated:

Comparison of Boots’s statement here with that made at the outset of the alliance (see p. 755) captures the distinctiveness of its alternative strategy. Moreover, Sainsbury’s extended health and beauty offer included some exclusive niche brands, which Boots had stocked for many years; so, it appears that Sainsbury’s was mimicking the Boots offer and gaining a “second-mover advantage” [48]. Formally speaking, each player has a set of strategies . The meaning of each strategy for each player is the following :Sainsbury’s will now press ahead with its plans for a new health and beauty range that it has been testing in five stores for a year. … The supermarket said it had already added 1,500 extra health and beauty products to its ranges over the past year [33].Sir Peter Davis, the chief executive, said: “The five trial stores have seen significant sales increases which show that we can create sufficient value by operating our own extended health and beauty department.”Boots said it would accelerate its plans for more stores on the edge of town, planning to double the number from 77 to more than 150 within three years.

- for Sainsbury’s means that Sainsbury’s does not retail its health and beauty products and Sainsbury’s lays out concession areas for Boots.

- for Sainsbury’s means that Sainsbury’s retails its proper health and beauty products in its stores. Sainsbury’s breaks the alliance down with Boots, and it does not lay out concession areas for Boots.

- for Boots means that Boots retails its health and beauty products only in Sainsbury’s stores.

- for Boots means that Boots retails its health and beauty products only in Boots stores.

The agreement between Sainsbury’s and Boots can be modelled as a dynamic game with imperfect information. A trial cooperation period starts (the initial state is Ally-Ally) during which Boots retails its own health and beauty products from within the main body of the Sainsbury’s store and Sainsbury’s withdraws from the retailing of health and beauty products. Later on, Sainsbury’s (initially cooperating) has the right to rearrange its decision between or . Successively, Boots chooses its strategy, or , without having any information about the opponent’s strategies. Such a game can be re-written in a normal form, as has been done in Table 1, in which the payoffs are detailed. From a game theoretical point of view, the interesting element of the dynamic game is the following: the initial state, Ally-Ally, can be successively disrupted by players’ strategies. 3

To identify the partner payoffs, we focus attention on footfall, assuming that Boots’s and Sainsbury’s underlying aim was to increase footfall in the trial stores. For simplicity, assume that in these stores’ catchments areas, there is a body of customers who will switch their health and beauty shopping between Boots and Sainsbury’s, depending on the strategies adopted by the two retailers. Suppose there are Sainsbury’s customers that are not already Boots customers and Boots customers that are not already shopping at Sainsbury’s, all of whom will shop at the Sainsbury’s stores when the Boots implants are in place and buy their groceries and their health and beauty products there. Let g denote the average spend per customer on groceries in the Sainsbury’s stores. The average amount, , spent on health and beauty products is more complicated, because there are four different prices in play, which we assume are reflected in the average customer spend:

where:

- is the average spend per customer in a Sainsbury’s store without the Boots implant, noting that supermarket prices for health and beauty items were lower than Boots prices [22];

- is the average spend per Sainsbury’s customer in a Sainsbury’s store after the Boots cooperation trial ended. The latter is resulting from the promised “improved customer offer” [49].

- is the average spend per customer in a Sainsbury’s store with the Boots implant, noting a little-publicised aspect of the trial that prices here could be lower than in Boots own outlets [32];

- is the average spend per customer in a Boots outlet.

The payoffs to the players from this group of customers depending on the players’ strategic choices are summarised in Table 1. There seems to have been a belief within Sainsbury’s that it would retain at least some of the Boots footfall [50] on termination of the trial. For simplicity, we have assumed that all the footfall would be retained; this is represented algebraically in the south-western-most element in Table 1.

Table 1.

Boots and Sainsbury’s play the Prisoners’ Dilemma.

| Boots’s choice | |||||

| Ally | Alternative | ||||

| Sainsbury’s choice | (fB + fS)h′B | (fB + fS)hB | |||

| Ally | |||||

| (fB + fS)g | fSg | ||||

| 0 | fBhB | ||||

| Alternative | |||||

| (fB + fS)(g + ) | fS(g + hS | ||||

| ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Sainsbury’s | Boots’s | ||||

| payoffs | payoffs | ||||

A game with the payoffs in Table 1 is classical a Prisoners’ Dilemma only if:

Although there is no algebraic reason why these conditions should be satisfied, it is very likely that these inequalities were actually satisfied, since, according to [33], and, according to [46], . Either way, Ally-Ally is not a Nash equilibrium.4

5.1. The Impact of a Third Player

Let us now assume that there is a third player, who attacks the i-th player with level , , normalised so that . If the third player attacks with level , payoff proportional to the respective level of attack is lost by the i-th player. These assumptions result in payoffs summarized in the bi-matrix in Table 2, which is another Prisoners’ Dilemma. These being the final payoffs, then the formation of an alliance would still not be a Nash equilibrium. We now turn our attention to the benefits of improved market performance promised in the first sentence of Section 2. We will also consider what will be the effect of an agreement between the parties to share improved market performance or cost reductions.

Table 2.

Initial payoffs with a third player.

| Boots’s choice | |||||

| Ally | Alternative | ||||

| Sainsbury’s choice | (1 ‒ qB)(fB + fS) | (1 ‒ qB)(fB + fS)hB | |||

| Ally | |||||

| (1 ‒ qB)(fB + fS)g | (1 ‒ qS)fSg | ||||

| 0 | (1 ‒ qB)fBhB | ||||

| Alternative | |||||

| (1 ‒ qS)(fB + fS)(g + ) | (1 ‒ qS)fS(g + hS) | ||||

| ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Sainsbury’s | Boots’s | ||||

| payoffs | payoffs | ||||

5.2. Alliances Offering Improved Market Performance

In this section, we assume that entering into an alliance improves the market performance of the partners by reducing the impact of competition from the third party. We noted in Section 2 that this effect was observed. Suppose, then, that, if an alliance is in place, when the third player attacks with level , payoff proportional to , where , is lost by the i-th player. The resulting payoffs are shown in Table 3.

In this situation, the conditions for Ally-Ally to be a Nash equilibrium are:

Recalling that, in our model, , Equation (1) shows that, however, in the improved market performance offered by an alliance, there are levels of attack by the third party that make Ally-Ally a Nash equilibrium.

Table 3.

Payoffs with a third player and improved market performance.

| Boots’s choice | |||||

| Ally | Alternative | ||||

| Sainsbury’s choice | (1 ‒ yqB)(fB + fS) | (1 ‒ qB)(fB + fS)hB | |||

| Ally | |||||

| (1 ‒ yqB)(fB + fS)g | (1 ‒ qS)fSg | ||||

| 0 | (1 ‒ qB)fBhB | ||||

| Alternative | |||||

| (1 ‒ qS)(fB + fS)(g + ) | (1 ‒ qS)fS(g + hS) | ||||

| ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Sainsbury’s | Boots’s | ||||

| payoffs | payoffs | ||||

5.2.1. Sharing the Benefits of Improved Market Performance

We now consider the effect of sharing the benefits of improved market performance within an alliance. The short-lived alliance described in Section 2 foundered on “how to divide up the revenues from health and beauty sales”. We model this process through one single-stage bargaining game. For simplicity, we assume that this is a generalised Nash bargaining game to divide a “pie” of size in which the disagreement point was . The observations from informed commentators noted in Section 2.3 imply that the bargaining powers of the players were not equal.

In algebraic terms, suppose that if the alliance is in operation, a fraction, α, of Boots’s health and beauty revenue is transferred to Sainsbury’s. Now, the conditions for Ally-Ally to be a Nash equilibrium are:

which can be written:

Let and denote the values of obtained by putting equal to zero and one, respectively, in Equation (5); that is:

Notice that both of these are decreasing functions of α.

5.2.2. Possible Implications for the Boots-Sainsbury’s Example

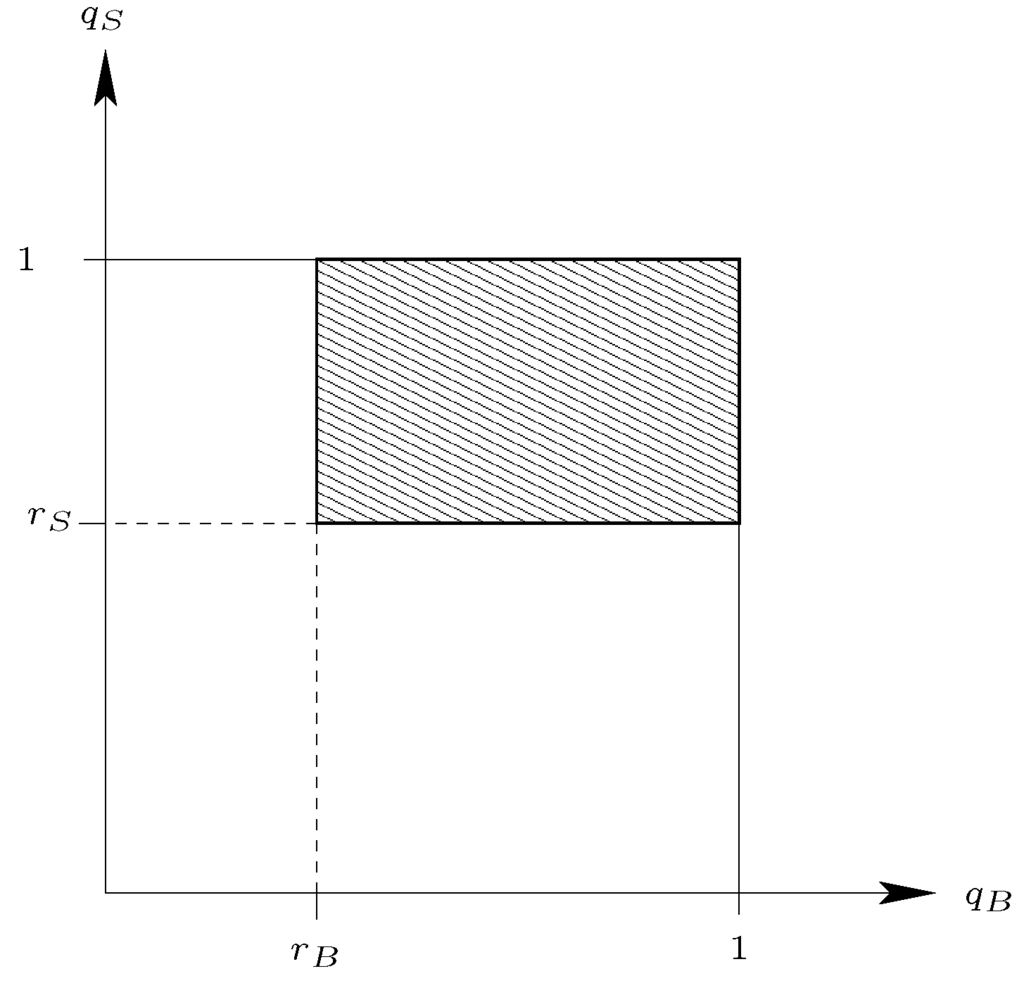

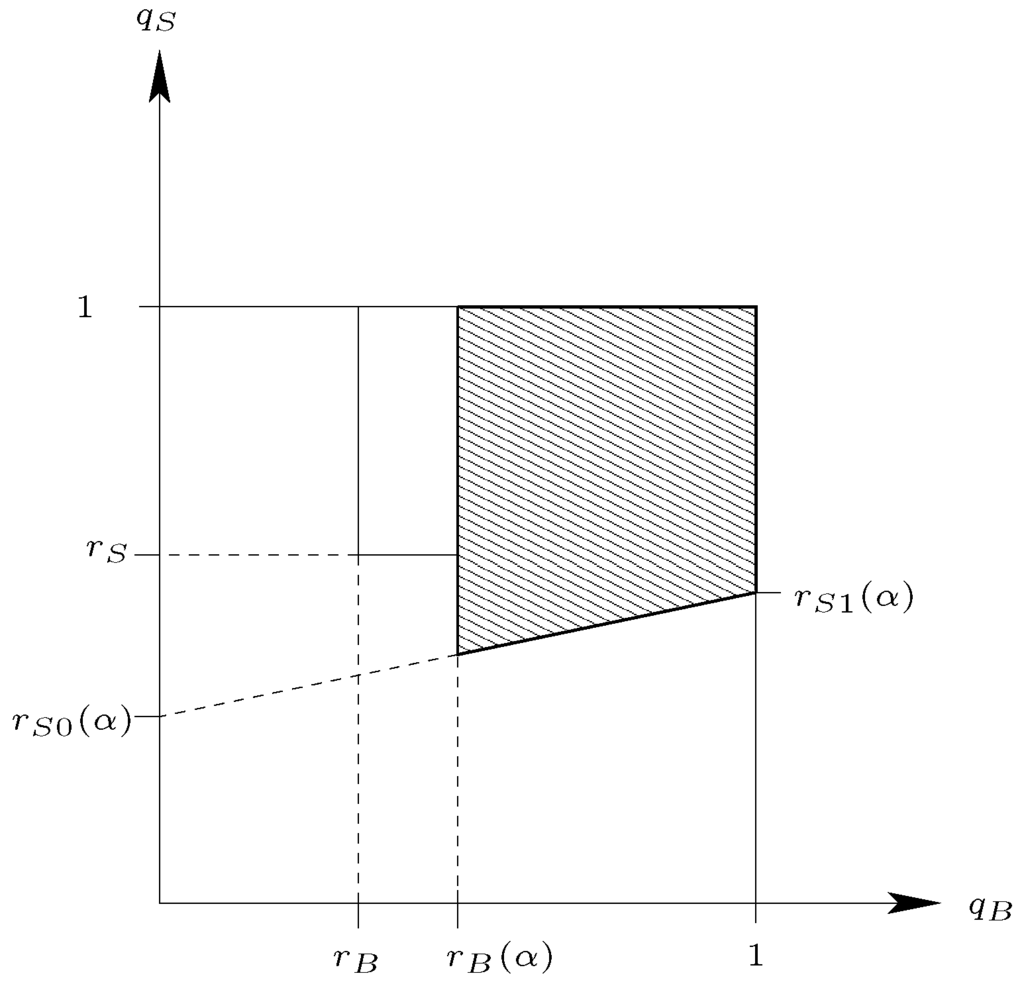

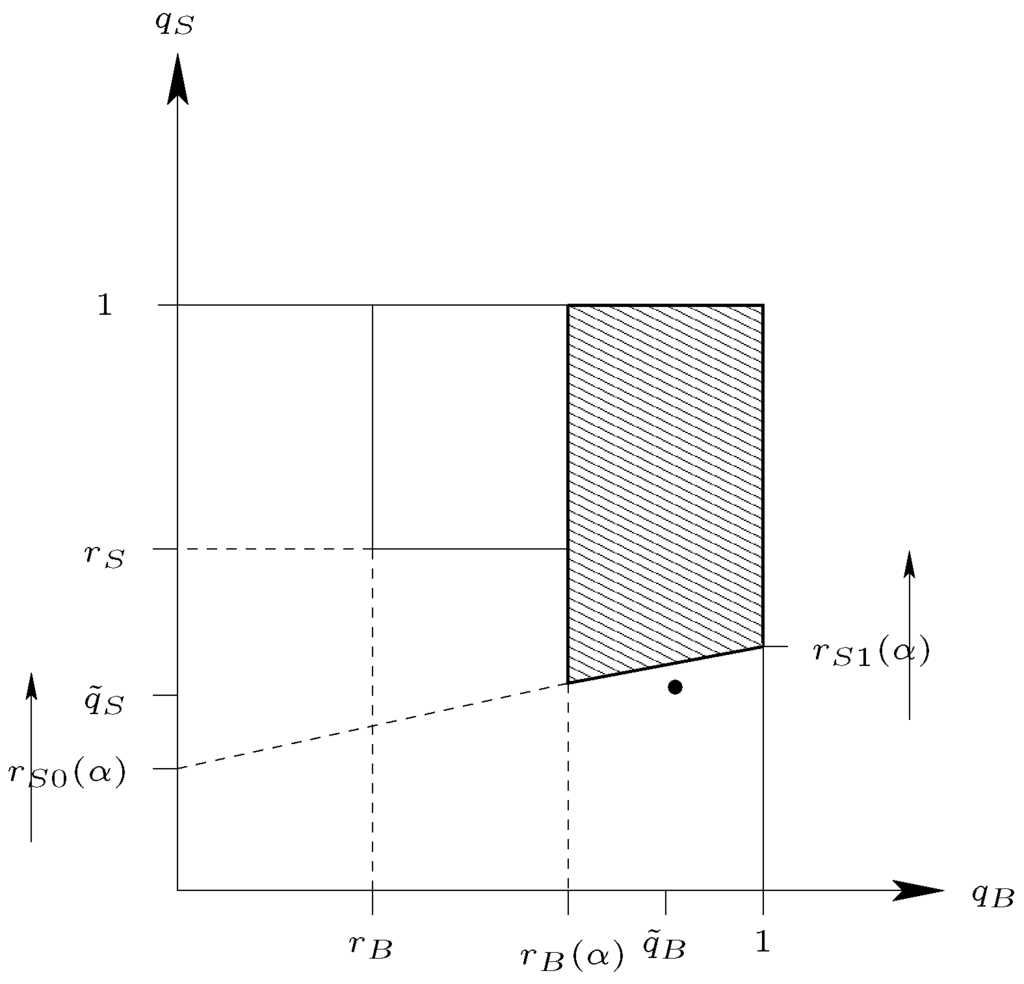

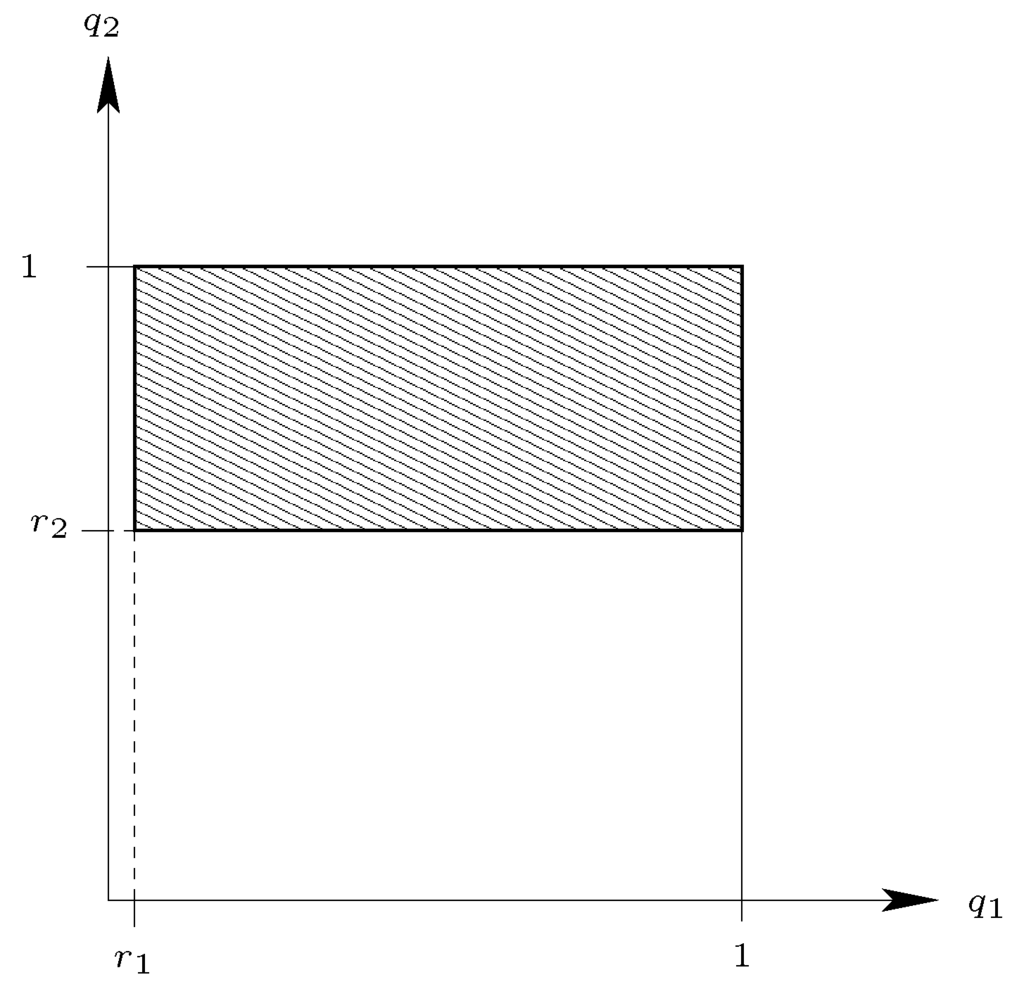

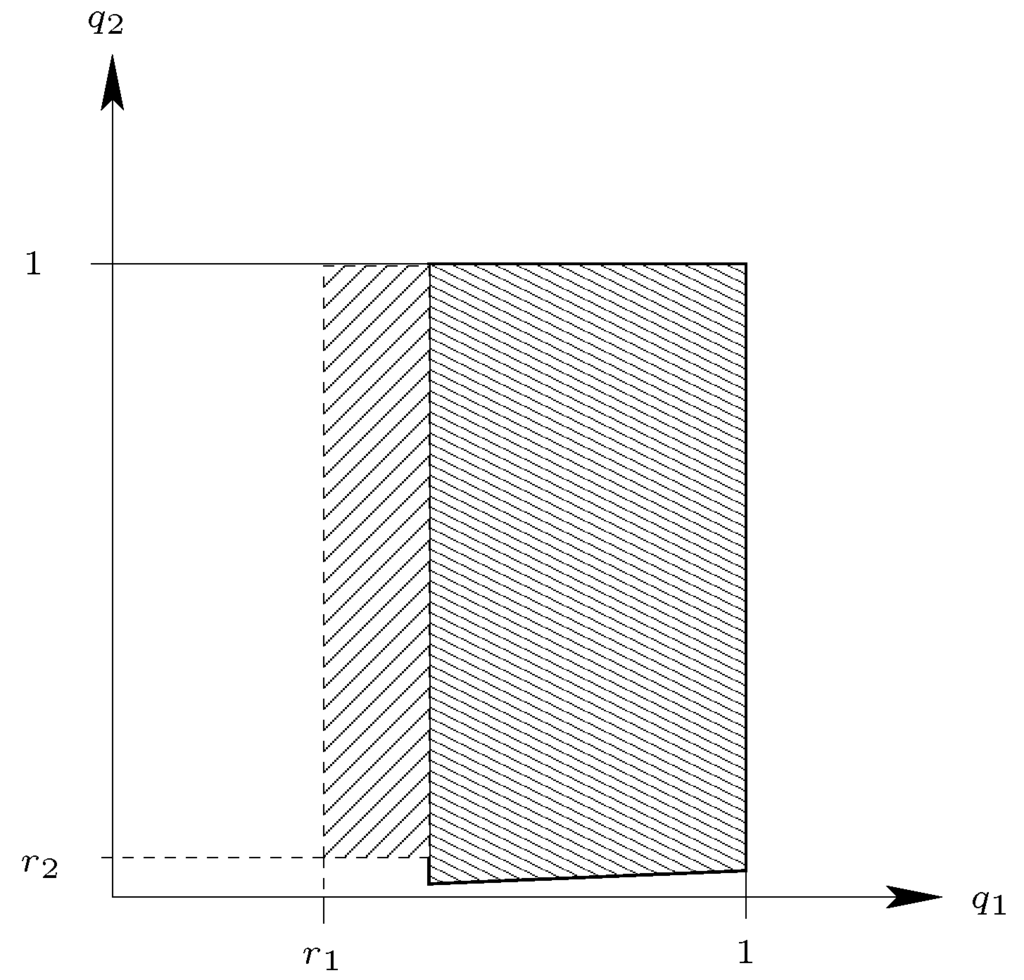

The foregoing analysis may offer an explanation of the sequence of events studied in Section 2. The key to this is the way the shape of the convex quadrilateral in the plane, defined by Equations (4) and (5), together with , changes as α changes and then as changes. We show a sequence of diagrams, starting with , when it is the rectangle shown in Figure 1, together with variants of Figure 2 for .

Figure 1.

The region in which Ally-Ally is a Nash equilibrium when improved market performance is available.

Figure 2.

The region in which Ally-Ally is a Nash equilibrium when sharing improved market performance is undertaken.

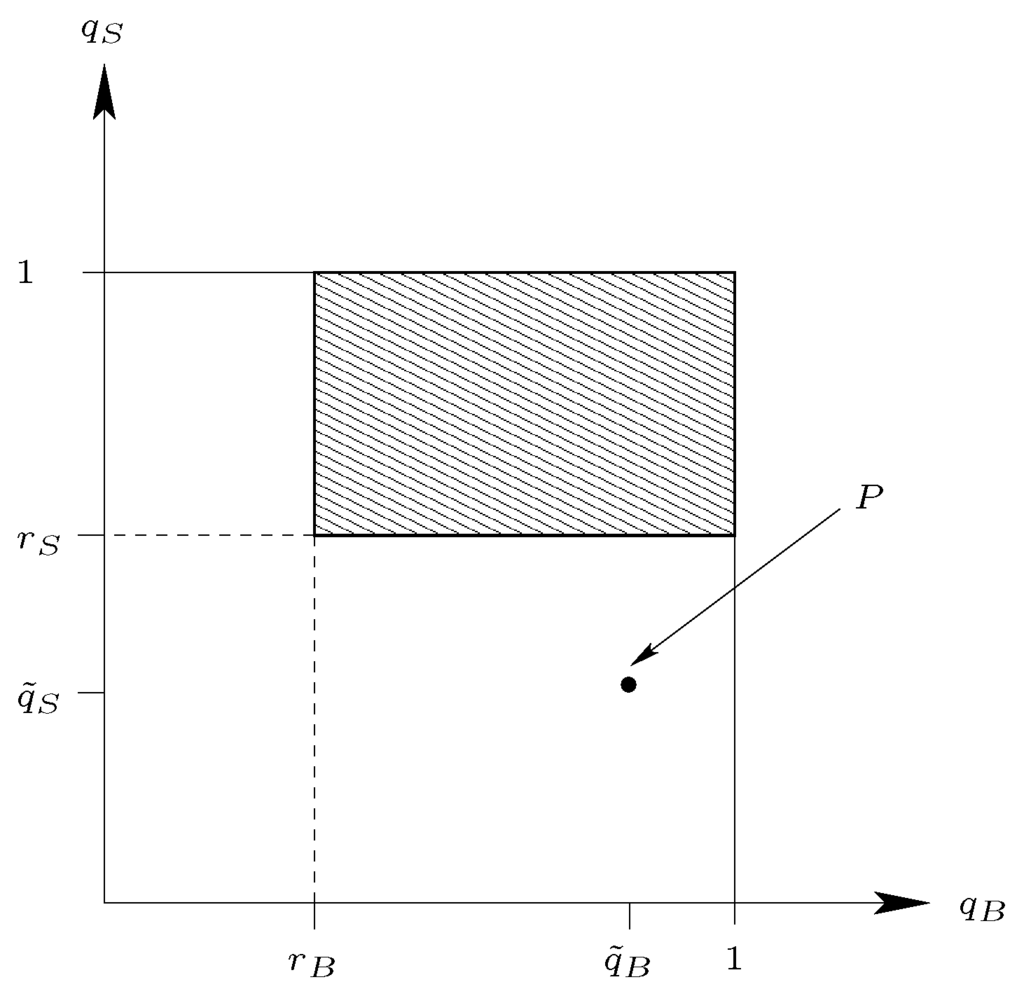

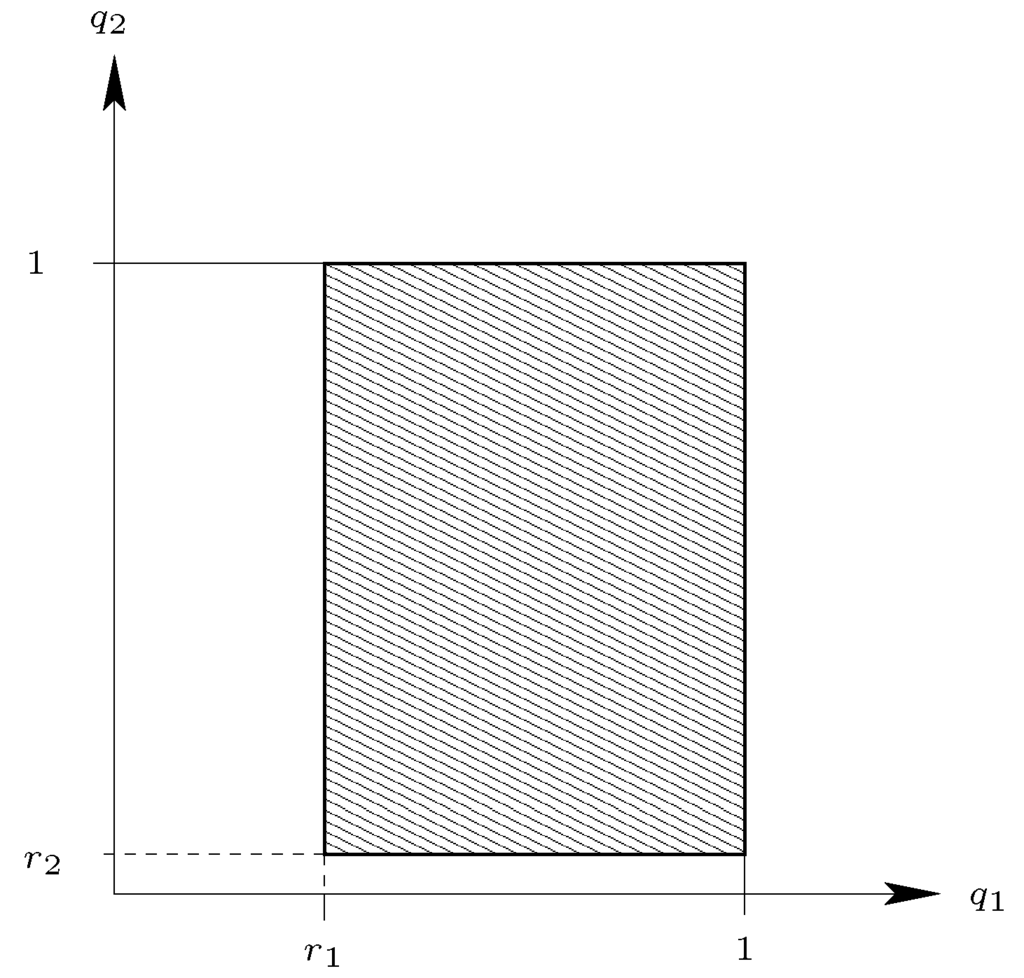

At the end of Section 2, we gave reasons for believing that Boots was under severe pressure from Tesco, whereas Sainsbury’s was under more modest pressure, illustrated by the point in Figure 3 in which is relatively small and is larger and showing how Ally-Ally might not be a Nash equilibrium when .

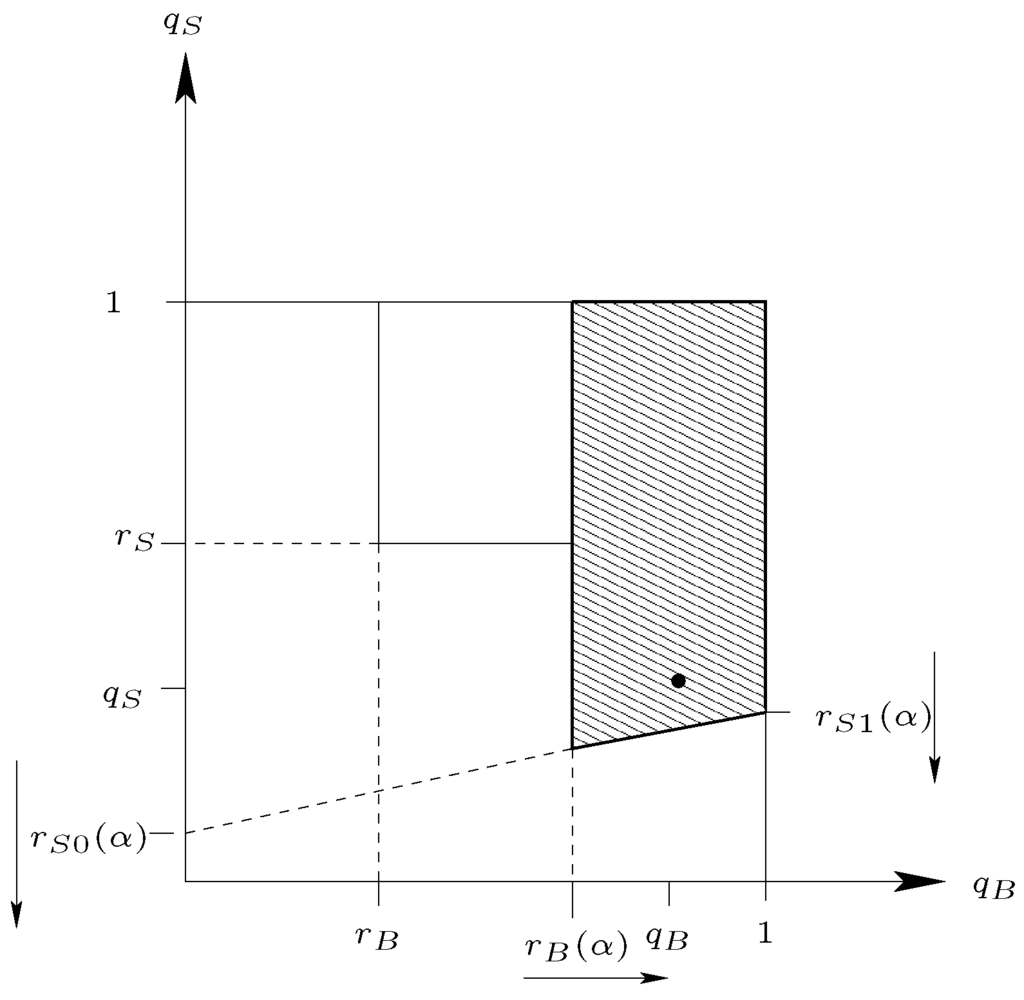

The effect of increased pressure on Boots would be to reduce its bargaining power and thereby to increase α—the share of the revenues from the health and beauty sales paid to Sainsbury’s. This would change the shape of the shaded quadrilateral to that shown in Figure 4, making Ally-Ally a Nash equilibrium. If this analysis is correct, then the sharing agreement tends to maintain the alliance when one of the partners comes under increased external pressure.

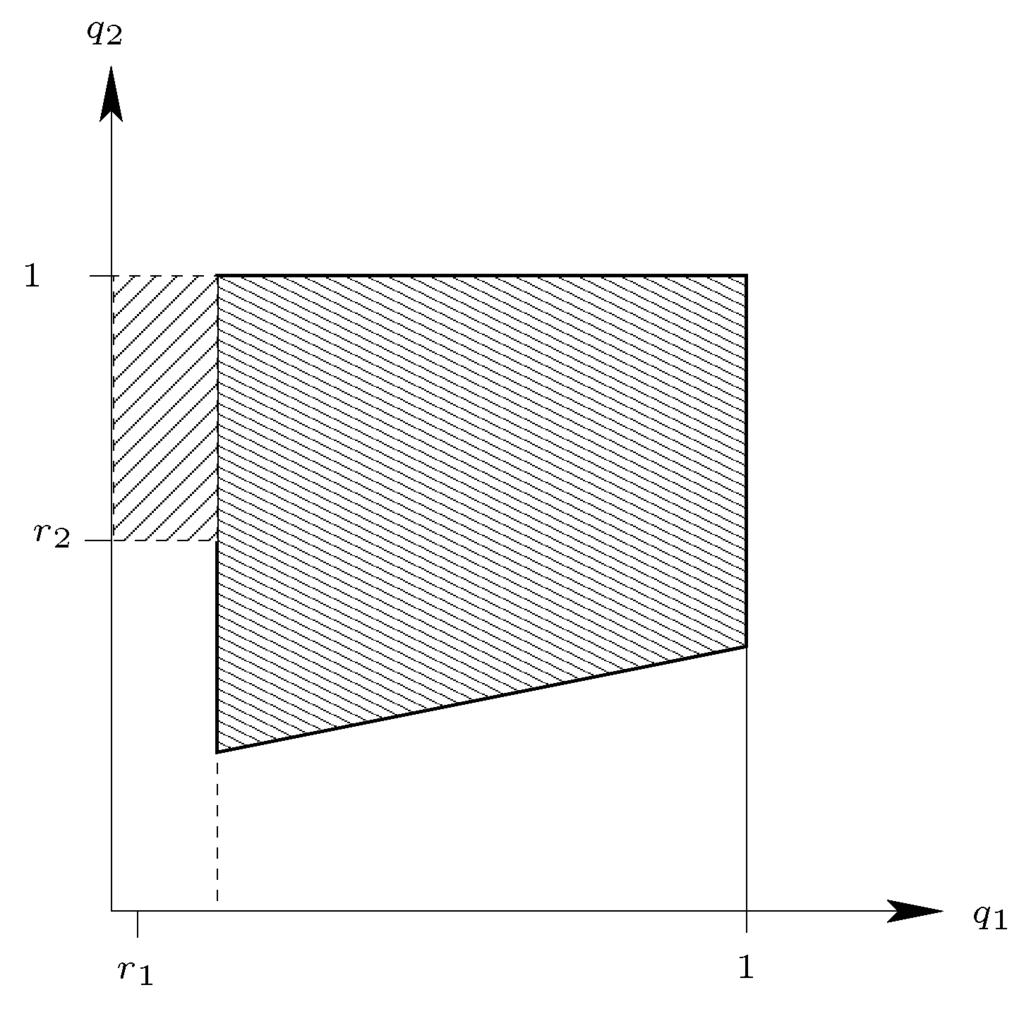

However, at the same time as bargaining about “appropriation of value by members” ([30](p. 48)), Sainsbury’s were planning an “improved customer offer” [49], that is, an increase in . This increases the values of and and changes the shape of the shaded quadrilateral again, to that shown in Figure 5, in which Ally-Ally is no longer a Nash equilibrium, and the alliance comes to an end.

Figure 5.

Ally-Ally is no longer a Nash equilibrium when is increased; the arrows show the direction of movement of the line in Equation (5) as increases.

More careful attention to the bargaining game could have maintained the alliance. In particular, the partners may well not have correctly evaluated the cost of failure to agree on revenue sharing, by conducting the bargaining game in isolation of the three-player Prisoners’ Dilemma. In fact, as we have seen, the two games interacted and, so, should have been considered within a multi-stage framework, so that a long-run equilibrium could have emerged and could have been encapsulated in a robust business model in the manner of the successful example provided by the Per Una implant that still exists in Marks and Spencers plc [51].

5.2.3. Further Implications

Other more general implications can be drawn from the model, though they were not observed in the specific situation discussed earlier. Firstly, if the allies had been under equally high pressure from the third player—that is, had the point, P, been close to the north-east corner of the unit square in the plane—then Ally-Ally would have been a Nash equilibrium at every stage, and the alliance would have continued in existence. Thus, a third player seeking to break up an alliance should apply asymmetric pressure. The closer the point, P, to the south-east corner of the unit square in the plane, then the larger the value of α needed to produce the configuration in Figure 4 and, hence, the harder the bargaining required to achieve it.

Secondly, the increase in the value of need not have resulted from Sainsbury’s explicit policy. This would have put pressure on Boots’s footfall, as obtaining prescription medicines would no longer differentiate its customer offer from that of supermarkets and would have offered supermarkets the opportunity to increase the average health and beauty spend per customer.

5.2.4. A View on Unilateral Commitments

We were not party to the decision-making process that led to the formation of the alliance in our scenario, nor is there any published account of which we are aware. However, we can say that while a unilateral commitment by one of the partners would have improved the prospects for the formation of an alliance, it would not have provided a guarantee. This is a rather less categorical conclusion than sometimes appears in the literature, and the asymmetry in our study has a significant bearing on our conclusions. We repeat that it is based on a theoretical analysis, not a deduction from real-life observation; to emphasise this, we will refer to the players as Player I and Player II.

We can model unilateral commitment to the formation and success of an alliance, understood as “actions that a particular company can take to alter only its own payoffs under particular outcomes” [37], by supposing that a player makes investments, whose effect is to change his or her parameters (decreasing y in Equation (1)), which are advantageous if and only if an alliance forms. It is easy to see that this makes an alliance more likely in that the player making the commitment will regard an alliance as advantageous over a wider range of pressure from the third player. However, such a unilateral commitment by one of the potential allies will not affect the decision of the other potential ally unless some further steps are taken.

As an illustration, consider an alliance offering improved market performance, as in Section 5.2, Suppose one or other of the players, but not both, makes an investment sufficient to ensure that his or her value is , in other words, entering into an alliance will insulate completely the part of his activity being modeled against depredations by the third player. This changes the conditions for a Nash equilibrium given by Equation (1) to:

if Player I makes the unilateral commitment, and to:

if Player II makes the unilateral commitment. These regions are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively, illustrating the point that one player’s unilateral commitment does not affect the decision of the other player.

Figure 6.

The region in which Ally-Ally is a Nash equilibrium when Player I makes a unilateral commitment to improved market performance.

Figure 7.

The region in which Ally-Ally is a Nash equilibrium when Player II makes a unilateral commitment to improved market performance.

Figure 8.

The change to the region in which Ally-Ally is a Nash equilibrium when Player I makes a unilateral commitment to improved market performance, which is then shared.

Figure 9.

The change to the region in which Ally-Ally is a Nash equilibrium when Player II makes a unilateral commitment to improved market performance, which is then shared.

Would revenue sharing as analysed in Section 5.2.1. improve the prospects for the formation of an alliance? The algebraic details can easily be modified to cover this and to give the modifications of Figure 2 shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

The shaded area in Figure 8 is greater than that in Figure 6, showing that the prospects for the formation of an alliance have improved, whereas a comparison of Figure 7 and Figure 9 shows the opposite effect. Of course, the numerical values of the parameters will make a difference to the extent of these changes, but it seems clear to us that there is no universal conclusion to be drawn about the efficacy of unilateral commitments.

6. Discussion, Conclusion and Lessons Learned

The main insight from our model is that the success or otherwise of an alliance is strongly influenced by the activity of a powerful third party in the same market sector. The game being played by (actual or potential) allies may no longer be a two-person Prisoners’ Dilemma if they are losing “payoff” such as market share or sales revenue to a third party, and an alliance may be the Nash equilibrium outcome. However, this requires that the alliance provide the allies with some additional benefits; the mere cessation of their hostilities is not enough. We found that improved market performance, one of the benefits of alliances previously mentioned in the literature, can provide this additional requirement.

Our deduction requires that, for an alliance to be the Nash equilibrium, it is necessary for the allies to be under pressure from the third party and losing significant payoff as a result. If this is happening in similar measure to both, then each ally’s decision of whether or not to seek an alliance is straightforward: is the loss that (s)he is suffering above a certain threshold? If one of the allies is under more pressure than the other, then they might agree to share the improved market performance to try to ensure that an alliance is the Nash equilibrium outcome, but now each ally’s decision is more complicated. They have to consider not only their own losses, but also those of their (potential) ally, before deciding whether or not to seek an alliance. What appears to underlie this is that each ally has to consider not only their own situation, but also whether an alliance will improve their ally’s situation sufficiently that the agreed shared benefits actually materialise. Notice that in order to do this correctly, particularly when the decision to form an alliance or not is finely balanced, each ally needs information about the other’s strategic situation—both players’ values of y in a more sophisticated model in which these were different.

This discussion of sharing agreements also affects the impact of unilateral commitments as analysed in Section 5.2.4. Our model suggests that these two strategies must go together, as a unilateral commitment by one of the potential allies may not, of itself, tempt a reluctant partner into the alliance, so some additional incentive, such as a sharing agreement, may be needed.

The proposed ending of the control of entry regulations for community pharmacies in the UK would have put Boots under significant pressure with, in this case, no pressure on Sainsbury’s, showing how the “business environment” can create a situation in which our model is relevant. We also note that all the variants of our model require non-zero pressure on both allies for an alliance to be a Nash equilibrium outcome, so they do not predict alliance between Boots and Sainsbury’s in this situation. Such an alliance would have been an embarrassment to the UK Office of Fair Trading (OFT), the regulatory body that made the proposal, as it was seeking to increase competition in the pharmacy market [52]. Our model thus points to a fortuitous outcome for OFT, as its report does not explicitly examine whether such an alliance might come about as a result of the proposed deregulation.

We have explored several scenarios and shed light on numerous other studies of alliance formation and dissolution by highlighting the importance of regulatory and competitive pressures. Useful lessons can be learned by other oligopolists contemplating entering into a strategic alliance. When considering establishing a strategic alliance, it is important to consider the impact of other players, such as changes in the market environment or decisions made by competitors, especially a dominant rival. The following more specific points emerge from our analysis:

- Any analysis of the success or failure of an alliance needs to look carefully not only at the capabilities and intentions of the allies, but at the wider circumstances. Moreover, there are no “obvious” quantitative/formal answers to questions about the viability or advisability of any particular alliance.

- It is possible that a competitor wishing to undermine the alliance will attack the partners in different ways, so they need to be able to recognise when this is happening and have an agreed response.

- If the alliance is to succeed, then the allies need to recognise at the outset that they may face different external pressures and internal motivations and have considered and agreed strategies for dealing with them.

- One should analyse carefully the interactions between the decisions that need to be made and their timing.

How firms address these last two points will depend on what ([27](p. 295)) calls embeddedness: that is, “the social structural patterns in exchange relations within markets”; we noted in Section 2 how commentators saw the Boots-Sainsbury;s alliance as something of a shotgun marriage. The author of [53] “proposes reach, richness, and receptivity as three fundamental mechanisms that jointly constitute a parsimonious model for explaining how network resources contribute to organizational performance.”

In future work, we will investigate the influence of third parties in inspection games related to the Prisoner’s Dilemma ([54] (Section 10.3)) and on the evolution of market shares in retail duopolies [55]. The case study on which this paper is based examined an alliance that [56] would be described as poorly embedded: in the eyes of some commentators, their alliance reduced rather than enhanced their reputation.

Acknowledgments

F. Ciardiello and J. M. Binner wish to mention the support of the Swedish Vetenkapsradet Research Council Grant reference Number 2009-20474-66896-29. The authors wish to thank an anonymous referee for his interesting comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- 1.Notwithstanding, in this paper, we have relied only on published material to support our arguments and conclusions.

- 2.A link-up with wine retailer Oddbins was even more short lived [8,11].

- 3.We avoid a further discussion about the extensive form of this game based on the agreements between the two companies, because it is out of the scope of this work. However, the dynamic model is not the unique way to describe this real life scenario.

- 4.Here, we justify how Sainsbury’s complete footfall fits naturally within a game theoretical situation, such as the Prisoners’ Dilemma. Therefore, we assume that a part of Boots customers will be retailed by Sainsbury’s if Sainsbury’s strategy is and Boots’s strategy is . We allow x to vary between zero and one, . Then, the south-western-most element in Table 1 becomes . After simple computations, if x satisfies the following condition:then modified Table 1 (where replaces ) still represents the Prisoners’ Dilemma. If Boots’s strategy is and Sainsbury’s is , Boots does not retail Sainsbury’s customers, because Sainsbury’s retails just groceries and Boots retails health and beauty products.

References

- Arend, R.J.; Seale, D.A. Modeling alliance activity: An iterated Prisoners’ Dilemma with exit option. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 1057–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyle, S. Boots and Sainsbury in Trial Link-Up; Financial Times: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boots and Sainsbury Notification Made Under the Competition Act 1998; Technical Report; Office of Fair Trading: Parramatta, Australia, 2001. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ (accessed on 13 November 2006).

- Koza, M.P.; Lewin, A.Y. The co-evolution of strategic alliances. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeheskel, O.; Shenkar, O.; Fiegenvaum, A.; Cohen, E.; Geffen, I. Cooperative wealth creation: Strategic alliances in israel medical-technology ventures. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2001, 15, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London Focus for Boots Store Revamp. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2002. Available online: http://www.pjonline.com/ (accessed on 4 June 2008).

- Boots Growth tonic May Be Blue Stores. The Daily Express. 2001. Available online: http://www.express.co.uk/ (accessed on 13 November 2006).

- Sainsbury’s and Oddbins Launch Wine Company. Press release 2 February 2001, J. Sainsbury plc, London. 2001. Available online: http://www.j-sainsbury.co.uk/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Outlook. The Independent. 2001. Available online: http://www.independent.co.uk/ (accessed on 18 July 2011).

- Interim results 21 November 2001. J. Sainsbury plc, Transcript of discussion at shareholders’ meeting. 2001. Available online: http://www.j-sainsbury.co.uk/ (accessed on 8 October 2009).

- Sainsbury and Oddbins have reached the end of the road with their joint venture Destination Wine Company. The Grocer, London 2002. Available online: http://www.thegrocer.co.uk/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Treanor, J. Boots and sainsbury in ugly divorce. The Guardian 2003. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/uk (accessed on 2 June 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ariño, A.; Ring, P.S. The role of fairness in alliance formation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1054–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.R. The Best Butter in the World: A History of Sainsbury’s; Ebury Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, G. Corporate Strategy in UK Food Retailing, 1980–2002. Technical Report, Centre for the Analysis of Risk and Regulation, London School of Economics. 2003. Available online: http://cep.lse.ac.uk/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Burt, S.; Sparks, L. Competitive Analysis of the Retail Sector in the UK. Technical Report, Department for Business Innovation and Skills; 2003. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ (accessed 2 June 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Burt, S.; Davies, K.; McCauley, A.; Sparks, L. Retail internationalisation: From formats to implants. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P. Price interventions in a Cournot oligopoly with a dominant firm. B. E. J. Theor. Econ. 2007, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T. Sainsburys Mulls Boots Merger. Mail on Sunday. 2001. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- A Global Supermarket Success. The Economist. 2001. Available online: http://www.economist.com/ (accessed on 2 June 2008); subscription required.

- The Competition Commission. Supermarkets: A Report on the Supply of Groceries from Multiple Stores in the United Kingdom. Technical Report, The Competition Commission. 2000. Available online: http://www.competition-commission.org.uk/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Ryle, S. Supermarket Pill Sales Give Boots Headache. The Observer. 2001. Available online: http://www.boots-uk.com/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Boots Group plc. Response to OFT Report—Boots to Open More Pharmacies. Press release 18 July 2001, Boots Group, London. 2003. Available online: http://www.boots-uk.com/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Hayward, N. Private Label in the UK (part 1): the Personalisation of Private Label. Euromonitor. 2002. Available online: http://www.euromonitor.com/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Annual Report 2001. Tesco plc. 2001. Available online: http://www.tescoplc.com/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Euromonitor. Boots on the Edge. Euromonitor. 2003. Available online: http://www.540euromonitor.com/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Gulati, R. Alliances and networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Teng, B.S. Partner analysis and alliance performance. Scand. J. Manag. 2003, 19, 279–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Ungson, G.R. Interfirm rivalry and managerial complexity: A conceptual framework of alliance failure. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Casseres, B. How Alliances Reshape Competition. In Handbook of Strategic Alliances; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Susini, J.P. The determinants of alliance performance: Case study of renault & nissan alliance. Econ. J. Hokkaido Univ. 2004, 33, 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, N. Boots products may be cheaper in Sainsbury’s. The Independent. 2001. Available online: http://www.independent.co.uk/ (accessed on 14 June 2009).

- Cope, N. Failed venture costs Boots and Sainsbury 10m. The Independent. 2003. Available online: http://www.independent.co.uk/ (accessed on 5 November 2009).

- Mitchell, W.; Singh, K. Survival of businesses using collaborative relationships to commercialize complex goods. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Half Year Results to 30th September 2003. Press release 6th November 2003, Boots Group plc. 2003. Available online: http://www.boots-uk.com/ (accessed on 3 June 2008).

- Ariño, A.; de la Torre, J. Learning from failure: Towards an evolutionary model of collaborative ventures. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Khanna, T.; Nohria, N. Unilateral commitments and the importance of process in alliances. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1994, 35, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhe, A. Strategic alliance structuring: A game theoretic and transaction cost examination of inter-firm cooperation. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 794–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Frèchette, G.; Qin, C.Z. Endogenous transfers in the Prisoner’s Dilemma game: An experimental test of cooperation and coordination. Games Econ. Behav. 2007, 60, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokoltsov, V.N. Nonexpansive maps and option pricing theory. Kybernetika 1998, 34, 713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, S. Three Essays on the Economics of Conflict and Contest. Ph.D Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport, A. N-Person Game Theory; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder, A.; Rusinowska, A. On some procedures of forming a multipartner alliance. J. Econ. Manag. Strateg. 2008, 17, 443–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J. Retail giants join forces. The Guardian. 2001. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/uk (accessed on 20 october 2013).

- Editorial: Boots and Sainsbury Plan Alliance. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2001. Available online: http://www.pjonline.com/ (accessed on 9 June 2008).

- Burt, S.; Sparks, L. Competitive Analysis of the Retail Sector in the UK; Technical Report; University of Stirling: Scotland, UK, January 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, K.; Dutta, B.; Ray, D.; Sengupta, K. A noncooperative theory of coalitional bargaining. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1993, 60, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, V.; Wait, A. Market entry dynamics with a second-mover advantage. B. E. J. Theor. Econ. 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury’s Rolls out Own Health and Beauty Offer. Press release 3 February 2003, J. Sainsbury plc, London. 2003. Available online: http://www.j-sainsbury.co.uk/ (accessed on 2 June 2008).

- Sainsbury kicks Boots into touch. Daily Mail. 2003. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- King, I. No row or acrimony as Davies ends era with Per Una and M&S. TheTimes. 2008. Available online: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- OFT Recommends Liberalisation of Pharmacy Market. Release Press Office of Fair Trading, London; 2003. Available online: http://www.oft.gov.uk/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Gulati, R.; Lavie, D.; Madhavin, R. How do networks matter? Unpacking the performance effects of interorganizational networks. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 207–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokoltsov, V.N.; Malafeyev, O.A. Understanding Game Theory; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Binner, J.M.; Fletcher, L.R.; Kolokoltsov, V.N. Existence and Uniqueness of Nash Equilibria in a Simple Lanchester Model of the Costs of Customer Churn. In Game Theory and Applications; Petrosjan, L., Mazalov, V.V., Eds.; Nova: New York, NY, US, 2013; Volume 10, Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, G.; Polidoro, F.; Mitchell, W. Structural homophily or social asymmetry? The formation of alliances by poorly embedded firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).