Endowment Inequality in Common Pool Resource Games: An Experimental Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model

2.1. Standard CPR Model

2.2. Behavioral Considerations I: Linear Other-Regarding Preferences

2.3. Behavioral Considerations II: Inequity Aversion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Model Hypotheses

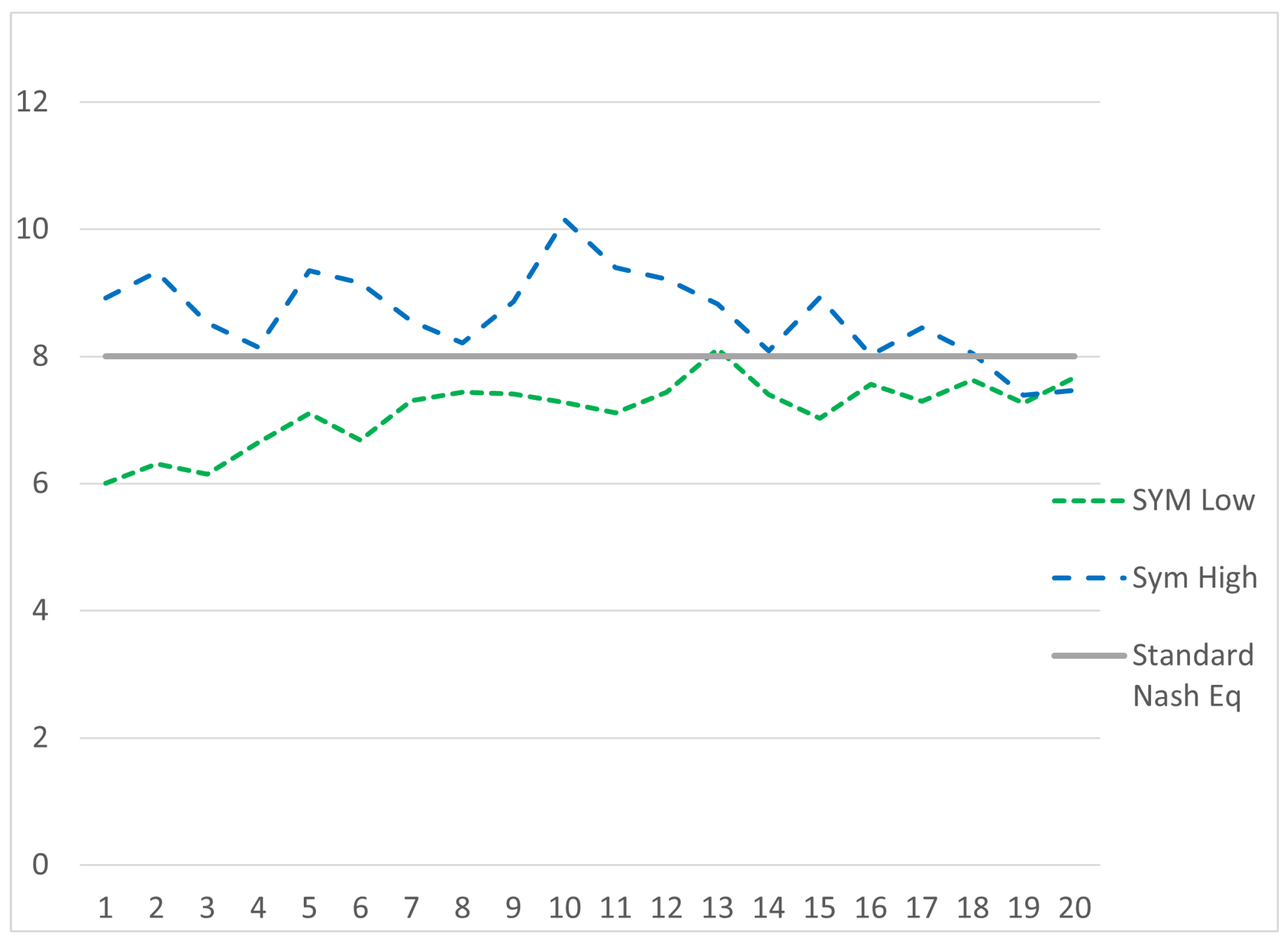

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Instructions for Participants

Appendix B. Experimental Data Reported by Session

| 1 | Heterogeneity along other dimensions has been discussed in the CPR literature. In an early examination, R. Johnson and Libecap (1982) study the impact of heterogeneous fisherman skill levels on fishery rents in the Texas shrimping industry. Baland and Platteau (1997) give a theoretical exploration of heterogeneous credit constraints in CPRs. Varughese and Ostrom (2001) examine the impact of heterogeneity (in location, wealth, and sociocultural factors) on the effectiveness of institutions, conservation, and collective action in Nepal. Moeltner et al. (2013) conduct an econometric study of the impact of differences in public institutions and policies, what they call “institutional heterogeneity.” | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Here, standard common pool resource model refers to a “vanilla” model without any of the institutional extensions present in much of the CPR literature, such as communication, monitoring, sanctioning mechanisms, or commitment devices. | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Lecoutere et al. nod to results in the literature on the impact of social status on collective action problems. However, in much of this literature, social status is defined broadly and may include individuals’ age, gender, religion, race, and income level. Since the experiment we conduct (1) randomly assigns individuals to either a high endowment or low endowment role in our inequality treatment; and (2) reports round-by-round individual-level data by anonymized player number only, high endowment participants can be interpreted as having a kind of “high social status” which is entirely driven by endowment heterogeneity. This is a unique contribution of our work to the discussion of social status, as we isolate one particular dimension—wealth—independent of any other demographic characteristics. | ||||||||||||

| 4 | This generalization from the Casari and Plott notation is helpful here, as individuals may consider transformations of that are not simple sums. | ||||||||||||

| 5 | This subgroup version of the linear other-regarding preferences model can be applied in any general context when two distinct groups of individuals share common characteristics. The asymmetric endowment model examined here is merely one such application. | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Using symmetry, then, we can compute the best response function for a type i individual as a function of only the (symmetric) : Similarly, the best response function for a j type individual as a function of only the (symmetric) is Solving this system yields the Nash equilibrium. | ||||||||||||

| 7 | This will be true for any : the type with the higher will invest less than the type with the lower . | ||||||||||||

| 8 | In the LORP model, the superscripts on , on , and on X will denote the perspective of the decision maker. The subscript on will denote the target of the other-regarding preference. Likewise, the negative subscript on or X denotes the type being summed, excluding the own type of the decision maker. For example, is the sum of all j types excluding the i type decision maker. But since the decision maker is not a j type, denotes the sum of all j types and includes all of those types. , on the other hand, is the sum of all j types excluding the j type decision maker. Here, the decision maker is herself a j type, so the sum includes only of the j types. | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Low endowment types outearning high endowment types in any given round would require some extreme behavior. It could occur if, say, all high endowment types set (no investment) and all low endowment types set —their maximum level of investment. While participants in the experiment do not directly observe others’ payoffs, they (a) are aware of the endowment distribution, and (b) directly observe both investment decisions of all participants and the total CPR value in each round of the experiment. | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Strategic substitutes characterizes an interaction in which an increase in the aggressiveness of one player decreases the marginal profitability of another player’s action. Games with strategic substitutes—simultaneous-move games in which all players exhibit strategic substitutes—are exemplified most easily as games of Cournot competition. In such games, players have downward-sloping best responses. Common pool resource games are games with strategic substitutes: as one player increases her extraction from the resource, this decreases the marginal profitability of extracting for every other player. This interpretation is consistent with Figure 2 of Falk et al. (2001), in which inequity averse best responses are described in terms of slope. | ||||||||||||

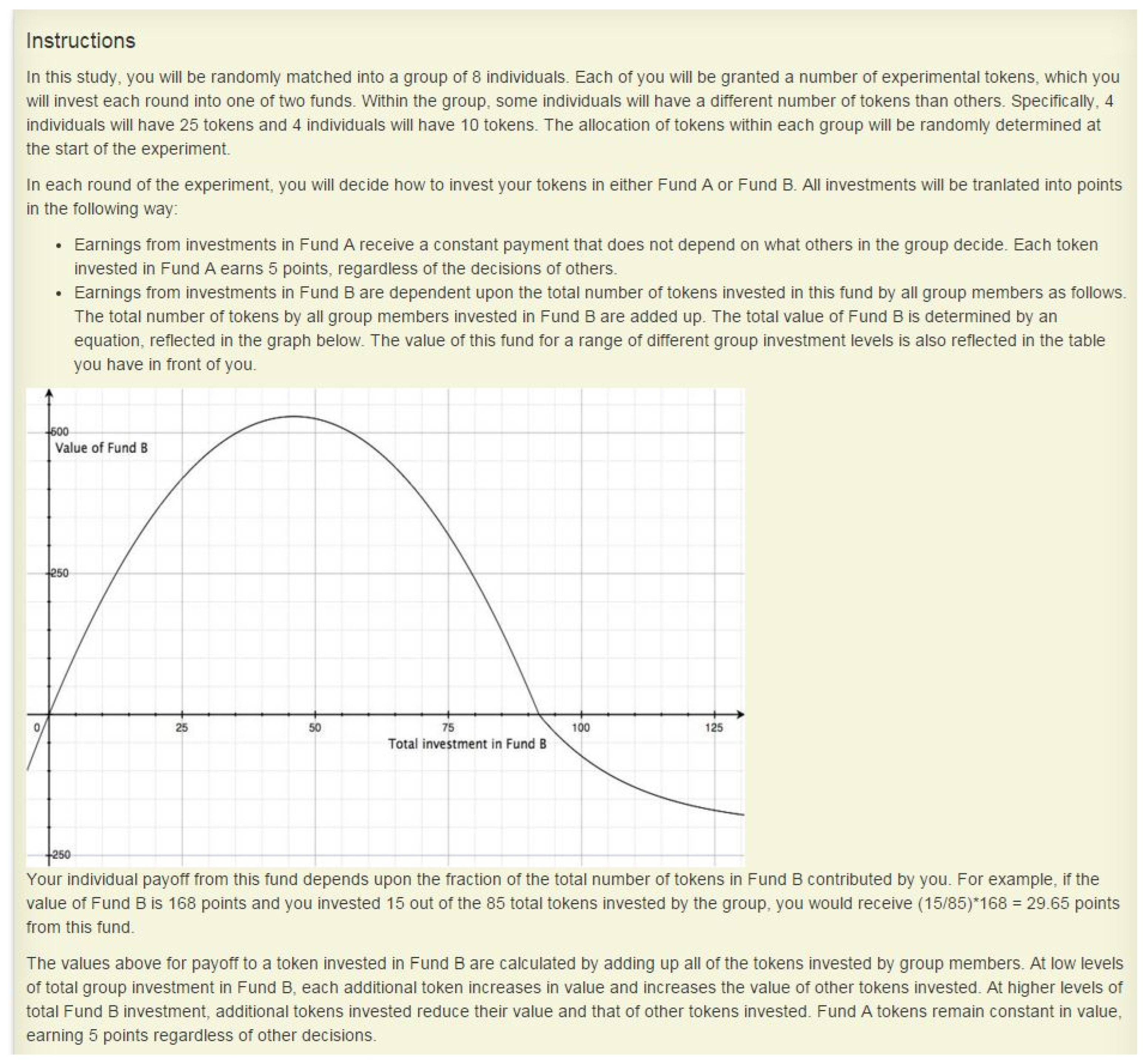

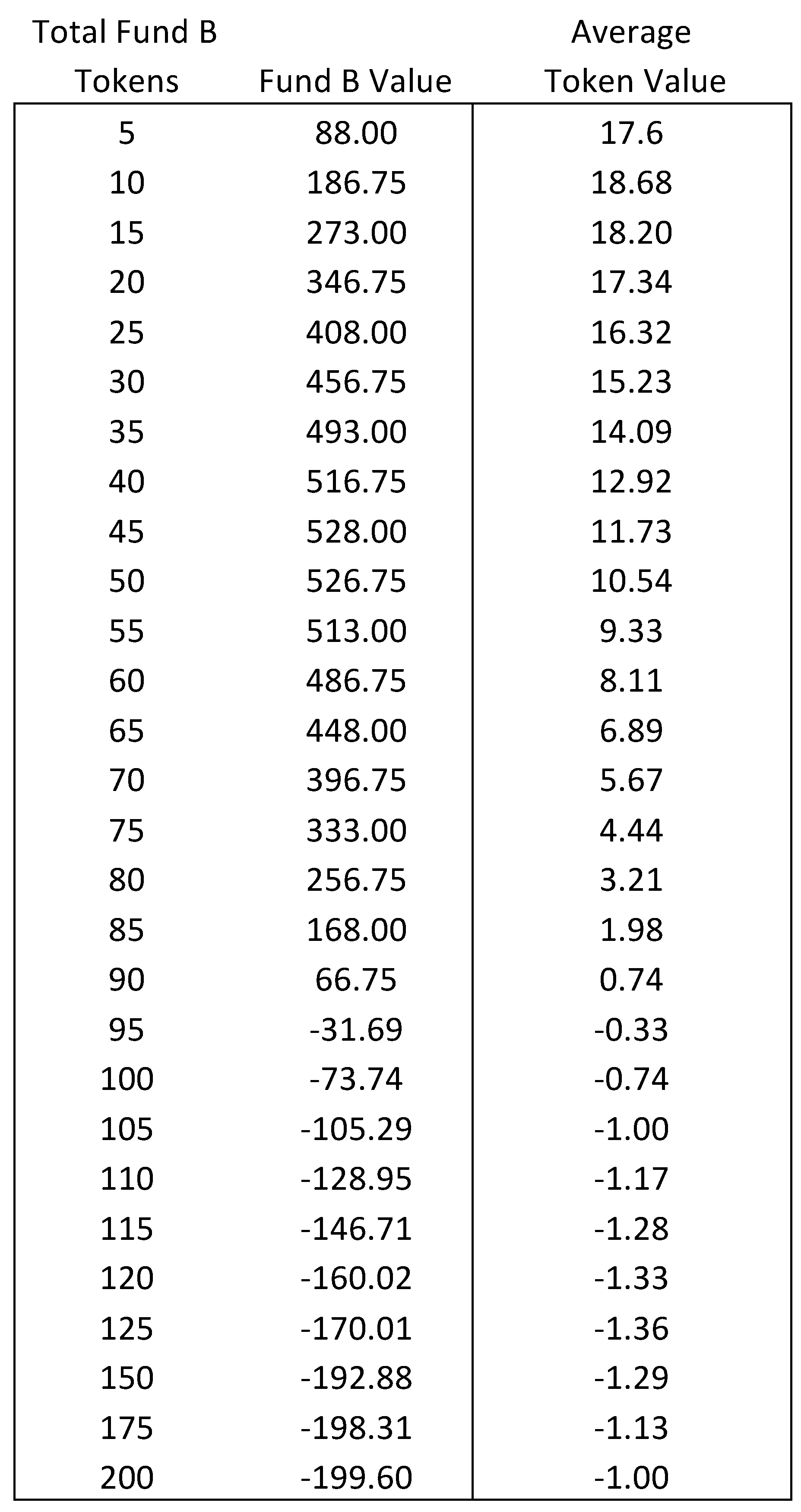

| 11 | This parametrization is chosen to be consistent with influential works in this literature, including OGW and Casari and Plott (2003). Additionally, we adopt the approach of Casari and Plott, allowing the CPR value to decrease asymptotically beyond high levels of investment. This can be seen in the Instructions graph presented to participants, and included in Appendix A. Formally, | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Framing the decision makers’ problem as an investment decision is consistent with the literature as far back as OGW. | ||||||||||||

| 13 | See Appendix A for a copy of subject instructions. | ||||||||||||

| 14 | This is equivalent to in the “subgroup” framework presented above. | ||||||||||||

| 15 | The work by Casari and Plott (2003) sheds light on reasonable ranges of LORP parameters in the model. Under the parameterization ), the resulting equilibrium investment levels are and . j types hit the lower bound on their choice space, and i types can only achieve this level of investment in an treatment. We therefore consider a LORP value of to be quite high. If, ), then and ; that is, a LORP value of is sufficiently altruistic on its own to cause an individual (in equilibrium) to invest 0 in the CPR. | ||||||||||||

| 16 | If, hypothetically, low endowment types had a high enough endowment to achieve the interior solution, NE values would be as follows:

| ||||||||||||

| 17 | This investment distribution would also hold under the (in our estimation) unlikely scenario that exclusively low endowment types are altruistic. | ||||||||||||

| 18 | We summarize two-group sessions in session format rather than group format because there are no discernible differences between group behavior that warrant group-level reporting. We present each individual session graphically in Appendix B. | ||||||||||||

| 19 | We also evaluated several other models, including a mixed-effect model with subject and group random effects and separately one with subject and group fixed effects. The results were substantively identical. | ||||||||||||

| 20 | These studies examine social dilemmas including pollution permit allocation (L. Johnson et al., 2006) and tax regime choice (Klor & Shayo, 2010). Rutstrom and Williams (2000) elicit preferences for income distribution with earned initial income endowments, finding that high endowment individuals are self-interested and reject income distribution. Côté et al. (2015) conduct an experiment with U.S. survey data on income, finding that where the degree of actual (or perceived) inequality is high, high-income individuals express less generosity. | ||||||||||||

| 21 | This study is identified by the authors as “Study 7: Tragedy of the Commons.” |

References

- Baland, J.-M., & Platteau, J.-P. (1997). Wealth inequality and efficiency in the commons Part I: The unregulated case. Oxford Economic Papers, 49(4), 451–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, E., & Croson, R. (2006). Income and wealth heterogeneity in the voluntary provision of linear public goods. Journal of Public Economics, 90(4–5), 935–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A., Shelton, J., & Exline, J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, F., Johansson-Stenman, O. L. O. F., & Martinsson, P. (2007). Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods. Economica, 74(296), 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, M., & Luini, L. (2009). Cooperation under alternative punishment institutions: An experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 71(2), 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, M., & Plott, C. (2003). Decentralized management of common property resources: Experiments with a centuries-old institution. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(2), 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K., Mestelman, S., Moir, R., & Muller, R. A. (1999). Heterogeneity and the voluntary provision of public goods. Experimental Economics, 2(1), 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral Economics and Finance, 9(1), 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, T., Kroll, S., & Shogren, J. (2005). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: Evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 57(3), 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. C., Ostrom, E., Walker, J. M., Castillo, A. J., Coleman, E., Holahan, R., Schoon, M., & Steed, B. (2009). Trust in private and common property experiments. Southern Economic Journal, 75(4), 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, S., House, J., & Willer, R. (2015). High economic inequality leads higher-income individuals to be less generous. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(52), 15838–15843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111(473), 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2001). Appropriating the commons A theoretical explanation. CESifoWorking Paper, No. 474. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/75841/1/cesifo_wp474.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. H., & Hutchens, R. M. (1993). Wages, seniority, and the demand for rising consumption profiles. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 21(3), 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayo, B., & Vollan, B. (2012). Group interaction, heterogeneity, rules, and co-operative behavior: Evidence from a common-pool resource experiment in South Africa and Namibia. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(1), 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Heap, S., Ramalingam, A., & Stoddard, B. (2016). Endowment inequality in public goods games: A re-examination. Economics Letters, 146(1), 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L., Rutstrom, E., & George, J. G. (2006). Income distribution preferences and regulatory change in social dilemmas. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 61(1), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R., & Libecap, G. (1982). Contracting problems and regulation: The case of the fishery. American Economic Review, 72(5), 1005–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Klor, E., & Shayo, M. (2010). Social identity and preferences over distribution. Journal of Public Economics, 94(3–4), 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoutere, E., D’Exelle, B., & Van Campenhout, B. (2015). Sharing common resources in patriarchal and status-based societies: Evidence from Tanzania. Feminist Economics, 21(3), 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 963–1002. [Google Scholar]

- McGinty, M., & Milam, G. (2013). Public goods provision by asymmetric agents: Experimental evidence. Social Choice and Welfare, 40(4), 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeltner, K., Murphy, J., Stranlund, J., & Velez, M. A. (2013). Institutional heterogeneity in social dilemma games: A Bayesian examination. In J. List, & M. Price (Eds.), Handbook on experimental economics and the environment. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. (1994). Rules, games and common-pool resources. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Rutstrom, E., & Williams, M. (2000). Entitlements and fairness: An experimental study of distributive preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 43(1), 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Varughese, G., & Ostrom, E. (2001). The contested role of heterogeneity in collective action: Some evidence from community forestry in nepal. World Development, 29(5), 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, M. A., Stranlund, J., & Murphy, J. (2009). What motivates common pool resource users? Experimental evidence from the field. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 70(3), 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J., Gardner, R., & Ostrom, E. (1990). Rent dissipation in a limited-access common-pool resource: Experimental evidence. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 19, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | Mean | St. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric | 3840 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Symmetric_Low | 3840 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Symmetric_High | 3840 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Asymmetric_Low | 3840 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Asymmetric_High | 3840 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Individual_investment | 3840 | 8.00 | 5.57 | 0.00 | 25.00 |

| Group_total_investment | 3840 | 64.01 | 13.63 | 21.00 | 115.47 |

| Player_payoff | 3840 | 148.72 | 149.35 | −65.25 | 767.75 |

| Player_endowment | 3840 | 17.50 | 7.50 | 10.00 | 25.00 |

| Treatment_round | 3840 | 10.50 | 5.77 | 1.00 | 20.00 |

| Treat_order_TR1 | 3840 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Treat_order_TR2 | 3840 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Treat_order_TR3 | 3840 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Hypotheses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 8 | 8 | |

| 5.28 | 10 | ||

| H3 | 6.4 | 10 | |

| 5.28 | 10 | ||

| 8.08 | 8.08 | ||

| H4 | 7.74 | 7.74 | |

| 8.37 | 8.37 | ||

| H5 | 11.07 | 5.54 | |

| 9.51 | 6.79 |

| Treatment | Sess 1 | Sess 2 | Sess 3 | Sess 4 | Sess 5 | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.75 | 7.54 | 6.87 | 7.20 | 6.35 | 7.02 | |

| (2.71) | (2.25) | (2.79) | (2.42) | (2.76) | (2.66) | |

| 8.96 | 8.39 | 9.07 | 7.94 | 8.91 | 8.65 | |

| (8.65) | (6.49) | (8.05) | (6.06) | (6.04) | (7.01) | |

| 8.76 | 8.43 | 7.99 | 8.38 | 8.39 | 8.34 | |

| (7.69) | (5.06) | (5.79) | (6.30) | (5.12) | (5.95) | |

| 4.99 | 5.54 | 5.20 | 6.58 | 5.69 | 5.68 | |

| (3.52) | (2.90) | (2.89) | (2.95) | (3.09) | (3.08) | |

| 12.52 | 11.33 | 10.79 | 10.18 | 11.09 | 10.99 | |

| (8.84) | (5.12) | (6.58) | (8.02) | (5.32) | (6.87) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ** | ** | |||

| ** | ** | |||

| (0.30) | ||||

| *** | −0.31 | |||

| (0.28) | ||||

| *** | ** | |||

| * | *** | |||

| 0.00 | ||||

| (0.01) | ||||

| -0.27 | ||||

| (0.28) | ||||

| Num. obs. | 3840 | 3840 | 3840 | 3840 |

| Num. groups | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.29 |

| 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|

| *** | ||

| *** | ||

| *** | ||

| Num. obs. | 480 | 480 |

| Adj. R2 |

| Endowment Type | Expected NE Payoff | Actual ASYM Treatment Mean Payoff |

|---|---|---|

| 141 | 139.2 | |

| 66 | 57.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milam, G.; Monaco, A. Endowment Inequality in Common Pool Resource Games: An Experimental Analysis. Games 2026, 17, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/g17010001

Milam G, Monaco A. Endowment Inequality in Common Pool Resource Games: An Experimental Analysis. Games. 2026; 17(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/g17010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilam, Garrett, and Andrew Monaco. 2026. "Endowment Inequality in Common Pool Resource Games: An Experimental Analysis" Games 17, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/g17010001

APA StyleMilam, G., & Monaco, A. (2026). Endowment Inequality in Common Pool Resource Games: An Experimental Analysis. Games, 17(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/g17010001