The Role of Brand Spillover on Firm’s Sourcing and Contract Decisions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Model Setup

4. Equilibrium Analysis

4.1. Results Under

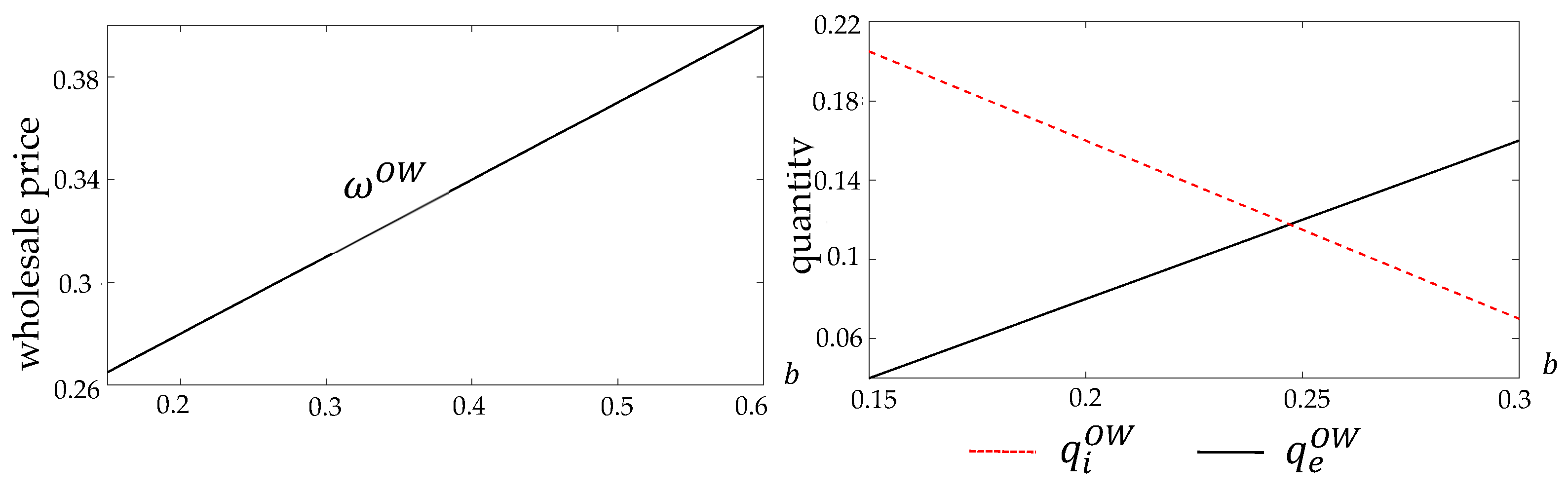

4.2. Results Under

4.3. Results Under

4.4. Results Under

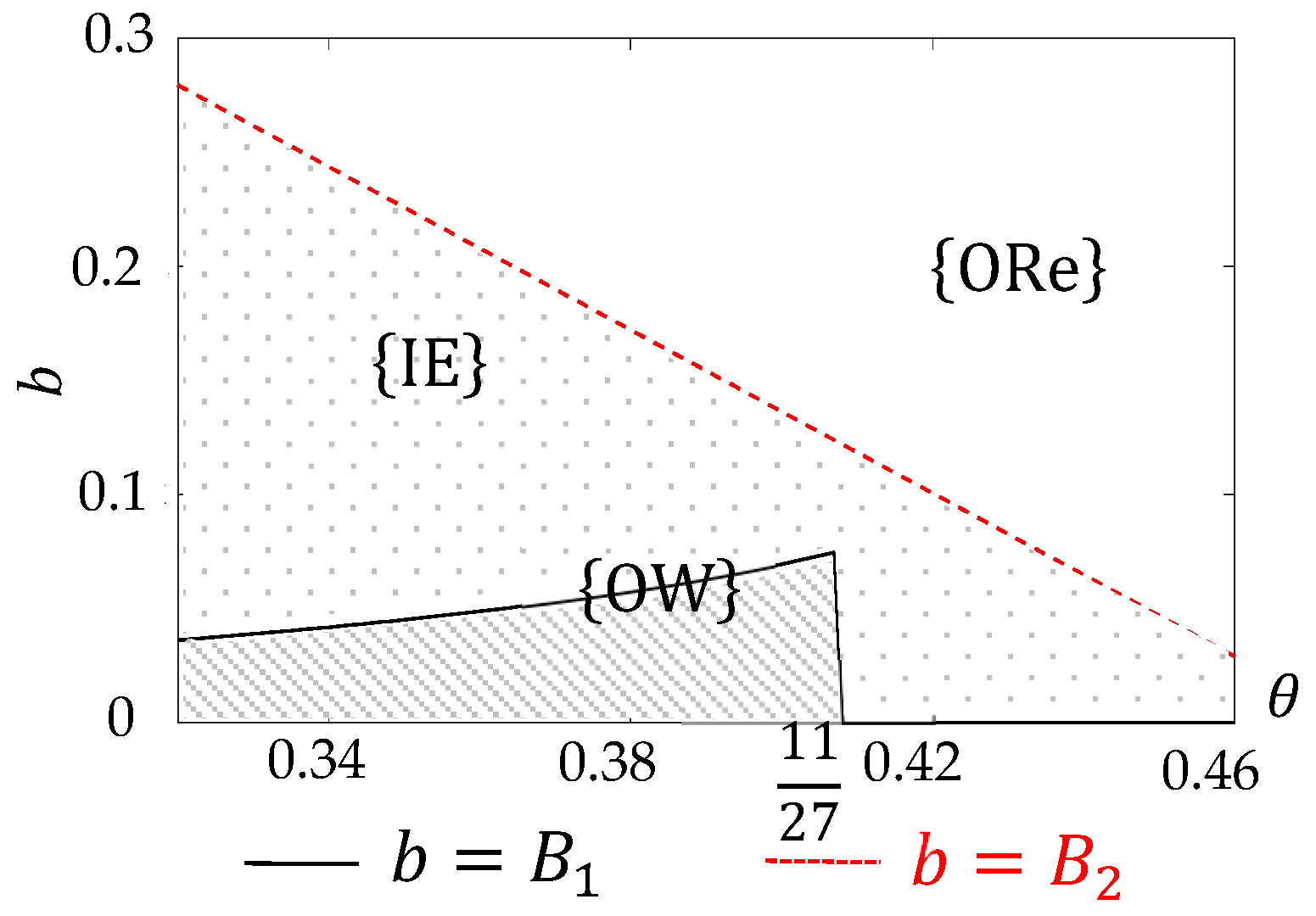

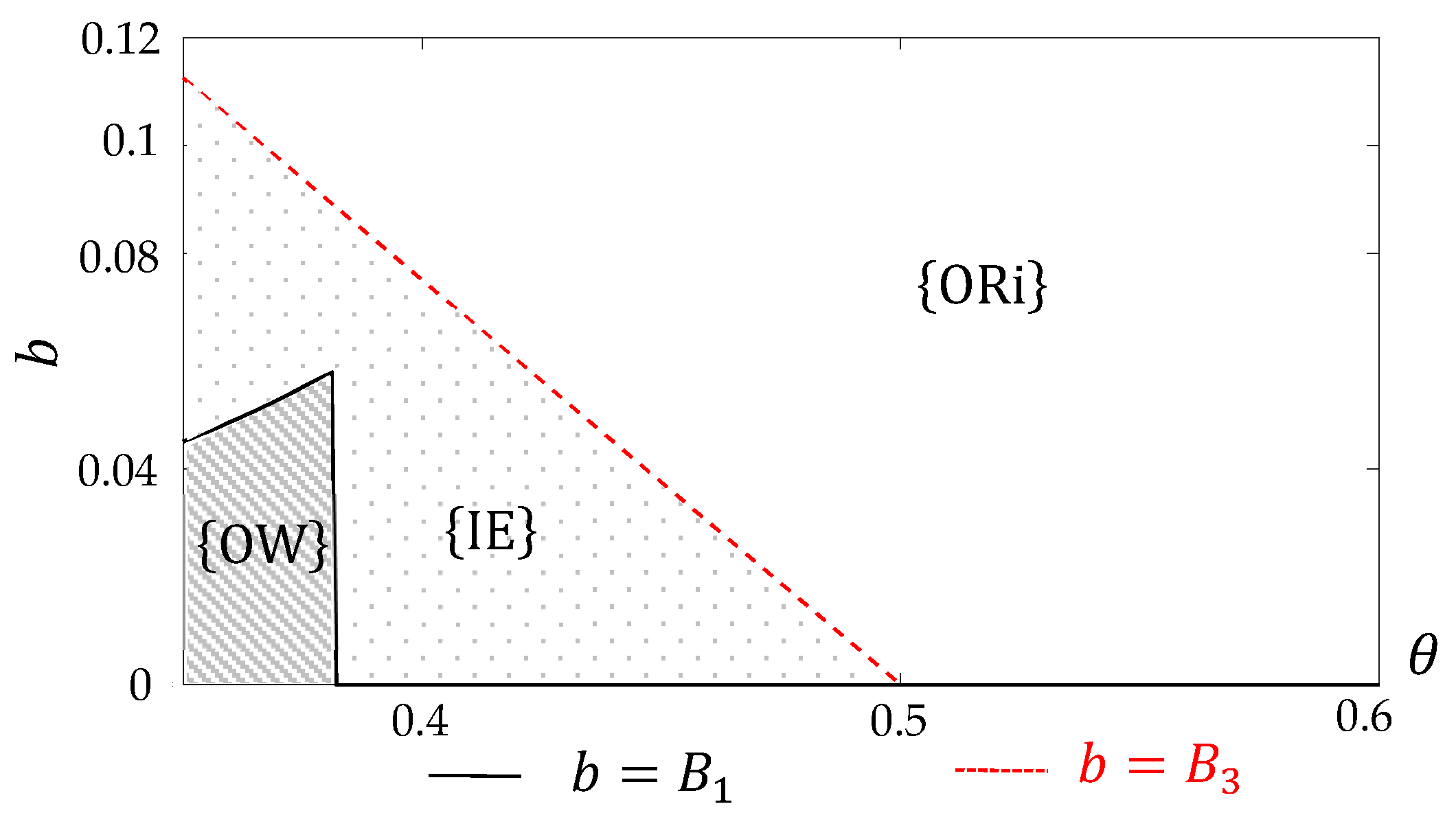

4.5. Equilibrium Sourcing Strategy

5. Extensions: Positive Production Costs

5.1. Incumbent’s Cost Advantage

5.2. Entrant’s Cost Advantage

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proofs

Appendix B. The Derivation of

Appendix C. The Formulas

| 1 | The formula is available in Appendix C due to its complexity. |

| 2 | The formula is available in Appendix C due to its complexity. |

| 3 | The formula is available in Appendix C due to its complexity. |

| 4 | is the intersection of and . |

| 5 | is the intersection of and ; is the intersection of and . |

References

- Anand, K. S., & Girotra, K. (2007). The strategic perils of delayed differentiation. Management Science, 53(5), 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, E., Iancu, D. A., & Swinney, R. (2017). Disruption risk and optimal sourcing in multitier supply networks. Management Science, 63(8), 2397–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arani, H. V., Rabbani, M., & Rafiei, H. (2016). A revenue-sharing option contract toward coordination of supply chains. International Journal of Production Economics, 178, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinadav, T., Chernonog, T., & Perlman, Y. (2015). Consignment contract for mobile apps between a single retailer and competitive developers with different risk attitudes. European Journal of Operational Research, 246(3), 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachander, S., & Ghose, S. (2003). Reciprocal spillover effects: A strategic benefit of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, A., & Servais, P. (2005). Co-branding on industrial markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(7), 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, A., & Tellis, G. J. (2016). Halo (spillover) effects in social media: Do product recalls of one brand hurt or help rival brands? Journal of Marketing Research, 53(2), 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G. P., & Kök, A. G. (2010). Competing manufacturers in a retail supply chain: On contractual form and coordination. Management Science, 56(3), 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G. P., & Lariviere, M. A. (2005). Supply chain coordination with revenue-sharing contracts: Strengths and limitations. Management Science, 51(1), 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G., Dai, Y., & Zhou, S. X. (2012). Exclusive channels and revenue sharing in a complementary goods market. Marketing Science, 31(1), 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Hu, X., Tadikamalla, P. R., & Shang, J. (2017). Flexible contract design for VMI supply chain with service-sensitive demand: Revenue-sharing and supplier subsidy. European Journal of Operational Research, 261(1), 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, G., Wang, Y., Gao, H., Liu, H., Liu, H., Song, Z., & Fan, Y. (2023). Coordination decision-making for intelligent transformation of logistics services under capital constraint. Sustainability, 15(6), 5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T., Chauhan, S. S., & Vidyarthi, N. (2015). Coordination and competition in a common retailer channel: Wholesale price versus revenue-sharing mechanisms. International Journal of Production Economics, 166, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernonog, T., & Levy, P. (2023). Co-creation of mobile app quality in a two-platform supply chain when platforms are asymmetric. European Journal of Operational Research, 308(1), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T. M., Wang, Y., & Shen, B. (2022). Selling to Profit-Target-Oriented retailers: Optimal supply chain contracting with bargaining. International Journal of Production Economics, 250, 108617. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, T. G., Khare, A., & Coulter, R. A. (2025). Spillover effects of sensory stimulation. European Journal of Marketing, 59(3), 501–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbs, J., Groza, M., & Rich, G. (2015). Brand spillover effects within a sponsor portfolio: The interaction of image congruence and portfolio size. Marketing Management Journal, 25(2), 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- El Ouardighi, F., & Kim, B. (2010). Supply quality management with wholesale price and revenue-sharing contracts under horizontal competition. European Journal of Operational Research, 206(2), 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, P. H. (1989). Managing brand equity. Marketing Research, 1(3), 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fazli, A., & Shulman, J. D. (2018). Implications of market spillovers. Management Science, 64(11), 4996–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q., & Lu, L. X. (2012). The strategic perils of low cost outsourcing. Management Science, 58(6), 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M., & Netessine, S. (2007). Strategic technology choice and capacity investment under demand uncertainty. Management Science, 53(2), 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H., Yang, Z., & Gurnani, H. (2022). Value of information with manufacturer encroachment. Production and Operations Management, 32(3), 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., Jayaswal, S., & Mantin, B. (2024). Who benefits from supplier encroachment in the presence of manufacturing cost learning? Production and Operations Management, 33(8), 1700–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., & Loulou, R. (1998). Process innovation, product differentiation, and channel structure: Strategic incentives in a duopoly. Marketing Science, 17(4), 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heese, H. S., & Kemahlioglu-Ziya, E. (2014). Enabling opportunism: Revenue sharing when sales revenues are unobservable. Production and Operations Management, 23(9), 1634–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B., Meng, C., Xu, D., & Son, Y. (2016). Three-echelon supply chain coordination with a loss-averse retailer and revenue sharing contracts. International Journal of Production Economics, 179, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiacheng, C., Haibo, Z., Ning, Z., Peng, Y., Lin, G., & Xuemin, S. (2016). Software defined internet of vehicles: Architecture, challenges and solutions. Journal of Communications and Information Networks, 1(1), 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Wang, S., & Hu, Q. (2015). Contract type and decision right of sales promotion in supply chain management with a capital constrained retailer. European Journal of Operational Research, 240(2), 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, N., Hammami, R., & Battaïa, O. (2022). Insourcing versus outsourcing decision under environmental considerations and different contract arrangements. International Journal of Production Economics, 253, 108589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, O. (2024). Cournot duopoly with cost asymmetry and balanced budget specific taxes and subsidies. Games, 15(4), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G., Rajagopalan, S., & Zhang, H. (2013). Revenue sharing and information leakage in a supply chain. Management Science, 59(3), 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvelis, P., & Zhao, W. (2016). Supply chain contract design under financial constraints and bankruptcy costs. Management Science, 62(8), 2341–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, D. M., & Wilson, R. (1982). Reputation and imperfect information. Journal of Economic Theory, 27(2), 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C. W., & Yang, S. J. S. (2013). The role of store brand positioning for appropriating supply chain profit under shelf space allocation. European Journal of Operational Research, 231(1), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. X., Zhou, Y. W., Li, J., & Zhou, S. (2013). Contract choice game of supply chain competition at both manufacturer and retailer levels. International Journal of Production Economics, 143(1), 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhang, R., & Liu, B. (2022). Encroachment strategy and revenue-sharing contract for product customization. RAIRO-Operations Research, 56(5), 3499–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y. F., Wang, Y., & Wu, Y. (2015). Consignment contracts with revenue sharing for a capacitated retailer and multiple manufacturers. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 17(4), 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Lv, J., Hou, P., & Lu, D. (2023). Disclosing products’ freshness level as a non-contractible quality: Optimal logistics service contracts in the fresh products supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research, 307(3), 1085–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Li, G., & Zheng, H. (2025). Dose free brand spillover always benefit? Procurement outsourcing in co-opetitive supply chains. Transportation Research. Part E, Logistics and Transportation Review, 197, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. (2024). Should competing suppliers with dual-channel supply chains adopt agency selling in an e-commerce platform? European Journal of Operational Research, 312(2), 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1982). Predation, reputation, and entry deterrence. Journal of Economic Theory, 27(2), 280–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithas, S., Chen, Z. L., Saldanha, T. J. V., & De Oliveira Silveira, A. (2022). How will artificial intelligence and Industry 4.0 emerging technologies transform operations management? Production and Operations Management, 31(12), 4475–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, I., Jeong, Y. J., & Saha, S. (2020). Investment and coordination decisions in a supply chain of fresh agricultural products. Operational Research, 20(4), 2307–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., Glaeser, C. K., & Su, X. (2025). Food ordering and delivery: How platforms and restaurants should split the pie. Management Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, O. C., Chintagunta, P. K., & Venkataraman, S. (2019). Consumer response to chapter 11 bankruptcy: Negative demand spillover to competitors. Marketing Science, 38(2), 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsule-Desai, O. D. (2013). Supply chain coordination using revenue-dependent revenue sharing contracts. Omega, 41(4), 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A. R., Qu, L., & Ruekert, R. W. (1999). Signaling unobservable product quality through a brand ally. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(2), 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehm, M. L., & Tybout, A. M. (2006). When will a brand scandal spill over, and how should competitors respond? Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J., & Wang, D. (2023). Contracting in hierarchical platforms. Economics Letters, 226, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B. L., & Ruth, J. A. (1998). Is a company known by the company it keeps? Assessing the spillover effects of brand alliances on consumer brand attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., & Vives, X. (1984). Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. The Rand Journal of Economics, 15(4), 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluis, S., & De Giovanni, P. (2016). The selection of contracts in supply chains: An empirical analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 41(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2023). Number of Tesla vehicles delivered worldwide from 1st quarter 2016 to 1st quarter 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/502208/tesla-quarterly-vehicle-deliveries/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Swaminathan, V., Reddy, S. K., & Dommer, S. L. (2012). Spillover effects of ingredient branded strategies on brand choice: A field study. Marketing Letters, 23(1), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., Yang, L., & Wang, M. (2025). Contract selection strategy for a multi-channel supply chain considering contract unobservability and channel spillover effect. Industrial Engineering and Management, 30(1), 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Thorbjørnsen, H., Dahlén, M., & Lee, Y. H. (2016). The effect of new product preannouncements on the evaluation of other brand products. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33(3), 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization (pp. 250–270). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vedantam, A., & Iyer, A. (2021). Capacity investment under Bayesian information updates at reporting periods: Model and application. Production and Operations Management, 30(8), 2707–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., & Shin, H. (2015). The impact of contracts and competition on upstream innovation in a supply chain. Production and Operations Management, 24(1), 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xiao, Y., & Yang, N. (2014). Improving reliability of a shared supplier with competition and spillovers. European Journal of Operational Research, 236(2), 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Li, G., Zheng, H., & Zhang, X. (2022). Contingent channel strategies for combating brand spillover in a co-opetitive supply chain. Transportation Research. Part E, Logistics and Transportation Review, 164, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Zha, Y., Li, L., & Yu, Y. (2022a). Market entry strategy in the presence of market spillovers and efficiency differentiation. Naval Research Logistics (NRL), 69(1), 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Zhang, F., & Zhou, Y. (2022b). Brand spillover as a marketing strategy. Management Science, 68(7), 5348–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. P., Liang, L., Liu, L., & Ieromonachou, P. (2017). Coordination contracts of dual-channel with cooperation advertising in closed-loop supply chains. International Journal of Production Economics, 183, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G., Xia, B., & Guo, J. (2022). Contract choice for upstream innovation in a finance-constrained supply chain. International Transactions in Operational Research, 29(3), 1897–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Duan, H., & Deng, S. (2025). Managing social responsibility efforts with the consideration of violation probability. European Journal of Operational Research, 323(3), 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Luo, J., & Wang, H. (2017). The role of revenue sharing and first-mover advantage in emission abatement with carbon tax and consumer environmental awareness. International Journal of Production Economics, 193, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Luo, J., & Zhang, Q. (2018). Supplier encroachment under nonlinear pricing with imperfect substitutes: Bargaining power versus revenue-sharing. European Journal of Operational Research, 267(3), 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Shi, M., & Goldfarb, A. (2009). Estimating the value of brand alliances in professional team sports. Marketing Science, 28(6), 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Aydın, G., Babich, V., & Beil, D. R. (2009). Supply disruptions, asymmetric information, and a backup production option. Management Science, 55(2), 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Hu, X., Gurnani, H., & Guan, H. (2018). Multichannel distribution strategy: Selling to a competing buyer with limited supplier capacity. Management Science, 64(5), 2199–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenipazarli, A. (2017). To collaborate or not to collaborate: Prompting upstream eco-efficient innovation in a supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research, 260(2), 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Gao, L., Zolghadr, M., Jian, D., & ElHafsi, M. (2023). Dynamic incentives for sustainable contract farming. Production and Operations Management, 32(7), 2049–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Donohue, K., & Cui, T. H. (2016). Contract preferences and performance for the loss-averse supplier: Buyback vs. revenue sharing. Management Science, 62(6), 1734–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Liu, Y., & Wang, M. (2024). Study of differentiated platform sales channel selection considering price discounts. Price: Theory & Practice, 3, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L., Nie, J., & Tan, Y. R. (2025). Game of brands: Managing brand spillover in a co-opetitive supply chain. Transportation Research. Part E, Logistics and Transportation Review, 199, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spillover Scope | Balachander and Ghose (2003); Simonin and Ruth (1998) | Single-firm or alliance | Competitive spillover (incumbent-entrant via sourcing) |

| Contract Mechanism | Cachon and Lariviere (2005); Palsule-Desai (2013) | Revenue share contract absent brand spillover | Revenue share contract + brand spillover |

| Sourcing Strategy | Y. Wang et al. (2014); X. Wu et al. (2022a) | Insourcing/outsourcing decoupled from contract | Sourcing + contract |

| Notation | Description |

| The entrant | |

| The incumbent | |

| Market price of the product | |

| Entrant’s original market potential, | |

| Level of brand spillover, | |

| Profit of the entrant | |

| Profit of the incumbent | |

| Decision variable | Description |

| Market demand of the product | |

| Wholesale price charged by the incumbent | |

| Commission rate | |

| Sourcing Strategy | Sensible Scenario |

| Case of insourcing strategy | |

| Case of outsourcing strategy with wholesale price contract | |

| Case of outsourcing strategy with revenue share contract (the entrant set ) | |

| Case of outsourcing strategy with revenue share contract (the incumbent set ) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jing, F.; Dong, J. The Role of Brand Spillover on Firm’s Sourcing and Contract Decisions. Games 2025, 16, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050055

Jing F, Dong J. The Role of Brand Spillover on Firm’s Sourcing and Contract Decisions. Games. 2025; 16(5):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050055

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Fei, and Junjie Dong. 2025. "The Role of Brand Spillover on Firm’s Sourcing and Contract Decisions" Games 16, no. 5: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050055

APA StyleJing, F., & Dong, J. (2025). The Role of Brand Spillover on Firm’s Sourcing and Contract Decisions. Games, 16(5), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050055