The Development of Prosociality: Evidence for a Negative Association between Age and Prosocial Value Orientation from a Representative Sample in Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Procedure and Measures

3. Results

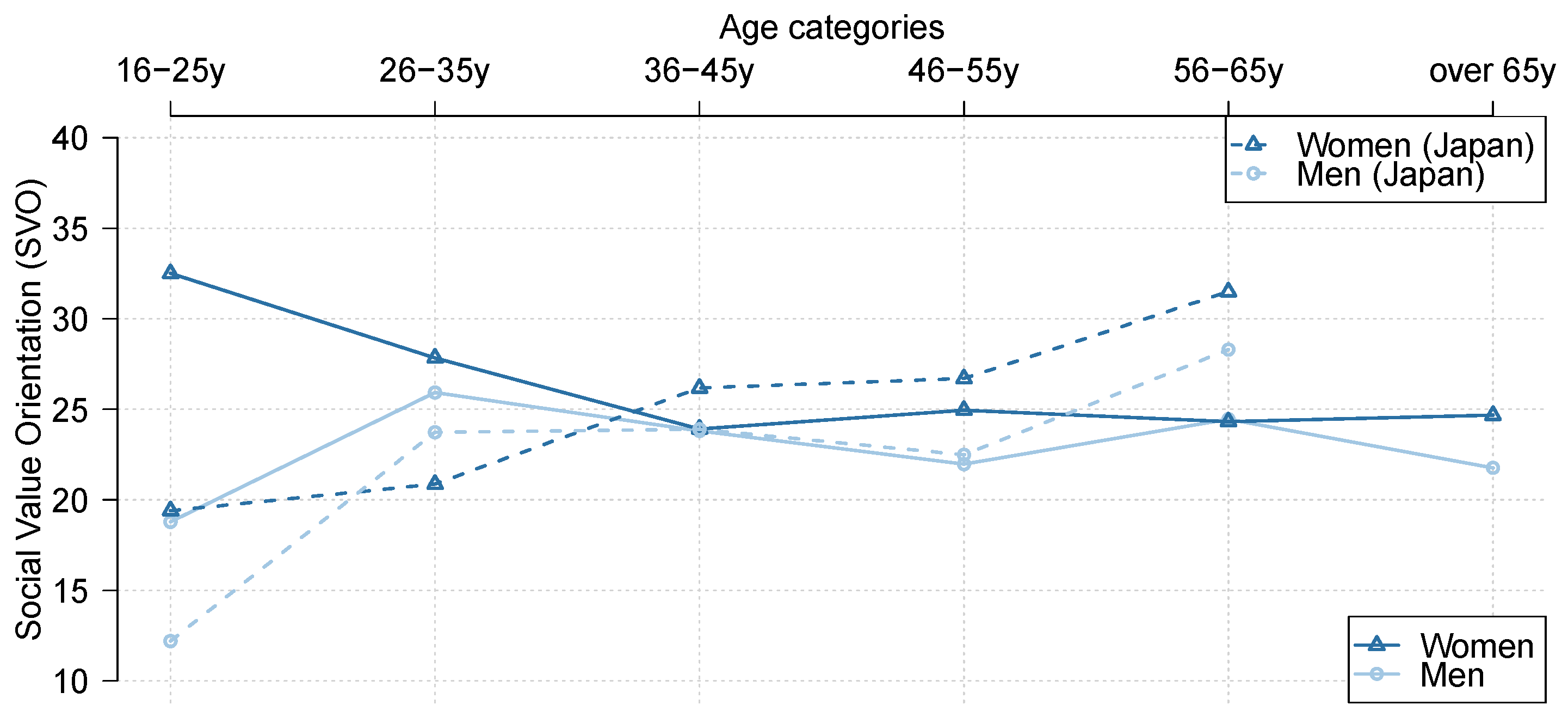

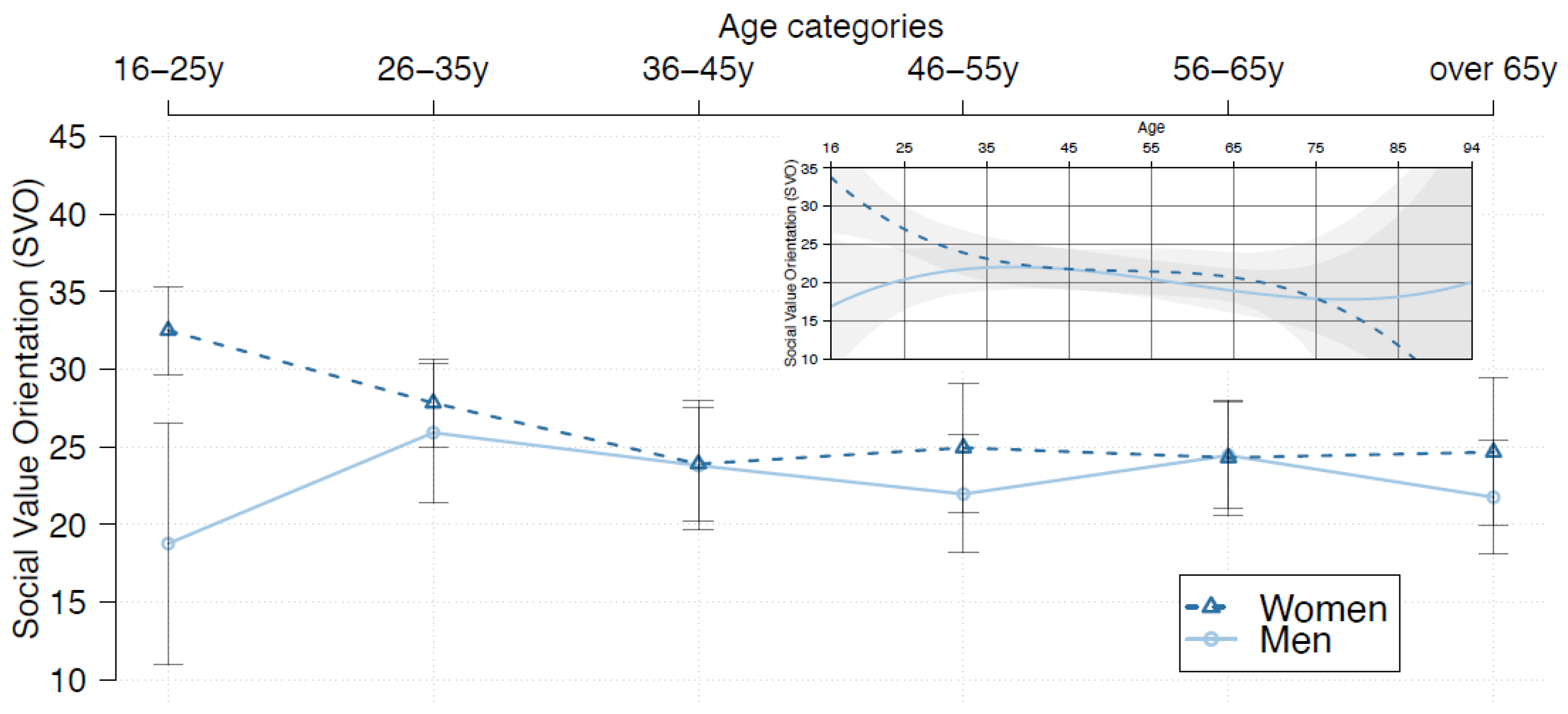

3.1. Gender and Prosociality

3.2. Age and Prosociality

3.3. Education, Political Orientation and Further Covariates and Prosociality

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Instructions

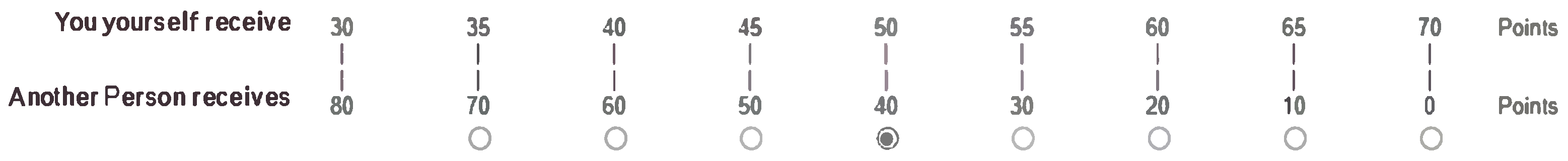

Appendix A.1. Translated Instructions of the SVO Slider Measure

- You and the other person are paid based on how you allocated points to yourself and the other person.

- Or you yourself are the “other person” and are paid according to the points that yet another participant allocated to you.

Appendix A.2. Allocation Pairs Used in the SVO Slider Measure Task

Appendix B. Supporting Figures and Tables

Appendix B.1. Supporting Figures

Appendix B.2. Supporting tables

| Variable | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVO angle | 777 | 24.23 | 15.1 | −16.26 | 61.39 |

| Age | 777 | 47.04 | 16.25 | 16 | 94 |

| Male | 777 | 0.484 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 777 | 2.71 | 1.27 | 1 | 5 |

| Compulsory school | 103 | ||||

| Vocational training | 328 | ||||

| Higher vocational training track | 129 | ||||

| University track (Matura) | 125 | ||||

| University/college | 92 | ||||

| City size | 777 | 3.00 | 1.66 | 1 | 5 |

| Below 5000 | 229 | ||||

| 5000 to below 10,000 | 113 | ||||

| 10,000 to below 50,000 | 124 | ||||

| 50,000 to below 100,000 | 49 | ||||

| 100,000 or more | 262 | ||||

| Immigrated | 777 | 0.03 | 0.177 | 0 | 1 |

| Political orientation | 777 | ||||

| Hofer | 321 | ||||

| Van der Bellen | 272 | ||||

| Undecided | 103 | ||||

| Non-voters | 81 | ||||

| Unemployed | 660 | 0.126 | 0.332 | 0 | 1 |

| Life satisfaction | 660 | 7.65 | 2.608 | 1 | 11 |

| Age Categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16–25 Years | 26–35 Years | 36–45 Years | 46–55 Years | 56–65 Years | 65 Years+ | |

| Ave. SVO | 16.94 | 22.43 | 25.04 | 24.69 | 30 | - 1 |

| Altruists | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0 | - 1 |

| Prosocials | 29.8 | 51.8 | 60.8 | 62.4 | 79.4 | - 1 |

| Individualists | 66 | 46.4 | 37.7 | 36.2 | 17.6 | - 1 |

| Competitors | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0 | 2.9 | - 1 |

| Covariates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age 1 | −0.042 | |

| (0.112) | ||

| Male | −0.151 | |

| (1.658) | ||

| Education | 1.336 | |

| (0.488) | ||

| Male × Age 1 | −0.065 | |

| (0.144) | ||

| Age 1 × Age 1 | 0.004 | |

| (0.004) | ||

| Age 1 × Age 1 × Age 1 | −0.0002 | |

| (0.0002) | ||

| City size 2 | 0.136 | |

| (0.349) | ||

| Immigrated | 0.378 | |

| (3.620) | ||

| Political orientation 3: (ref. planned voting for independent candidate VdB) | Right-wing party voter | −3.400 |

| (1.358) | ||

| Undecided voter | 0.822 | |

| (1.847) | ||

| Non-voter | −0.966 | |

| (1.981) | ||

| Male × Age 1 × Age 1 | −0.008 | |

| (0.005) | ||

| Male × Age 1 × Age 1 × Age 1 | 0.0004 | |

| (0.0003) | ||

| Constant | 21.997 | |

| (2.286) | ||

| Obs. | 700 | |

| R2 | 0.061 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.043 |

| 1 | The age category 10–16 years, which was also sampled during a Board Games Fair, revealed significantly lower cooperation rates; however, the authors could not replicate the effect among 12–13 years old young teenagers sampled at a local school. |

| 2 | Further information on the panel quality, including offline recruitment measures, is available under https://norstatgroup.com/offering/online-data-collection (accessed on 5 March 2021). |

| 3 | The study was conducted during the 2016 presidential elections in Austria. Respondents were asked to indicate their voting preferences between the rather left-wing liberal candidate A. van der Bellen (independent; formerly associated with the Austrian green party) and the right-wing nationalistic candidate N. Hofer (FPÖ; national-conservative right-wing party). Voting preferences could be indicated as undecided, in favor of either one of the two candidates, or by saying that they are not planning to vote. |

| 4 | The variable was coded 0 = if respondents indicated that they had some form of a working contract (full-time, part-time, marginally employed, vocational training or on temporal leave), were self-employed, or in pension, and 1 = otherwise. |

| 5 | The tangent of the SVO angle can also be interpreted as the weight an agent assigns to the payoff of an anonymous other person under the given conditions of the Slider Measures allocation pairs. |

| 6 | Participants with intransitive choices in the six SVO slider tasks revealed significantly lower and less volatile SVO measurements suggesting more random response patterns, but other than that did not significantly differ with respect to age, sex, education, and response time (all t(775) ≥ 1.72, all p ≥ 0.08). |

| 7 | It has to be noted that there is also one more study using the SVO slider measure, which reports no age effects [49]. However, it has to be acknowledged that their sample of 63 adults was relatively small and narrow with respect to age (the reported mean age was 31.92 with a standard deviation of 1.01 years) and therefore somewhat less informative for the age-related development of prosociality. |

| 8 | The average SVO angle and percentage of altruists, prosocials, individualists, and competitors for the different age groups in Japan calculated from data reported in [14] can be found in Table A1 in the Appendix B. |

| 9 | Further suggestive evidence in this direction has been reported by Carpenter and colleagues [17]. They found a positive age-related effect on public good contributions in Vietnam (similar to Japan) but not in Thailand. Although the comparison is not reported in the paper, it might be that Vietnamese emerging adults, similar to Japanese emerging adults, reveal lower levels of prosociality than Thai emerging adults, likewise similar to Austrian emerging adults. Such differences could, as we suggest, be linked to cross-cultural differences promoting competitiveness during childhood and adolescence. |

| 10 | The same argument regarding the possible confounding age-related effect of social desirability applies to the study from Japan since their used SVO Slider Measure was also non-incentivized. |

References

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. Why Social Preferences Matter—The Impact of Non-Selfish Motives on Competition, Cooperation and Incentives. Econ. J. 2002, 112, C1–C33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. The Nature of Human Altruism. Nature 2003, 425, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, B.R.; Silk, J.B.; Henrich, J.; Barrett, H.C.; Scelza, B.A.; Boyette, A.H.; Hewlett, B.S.; McElreath, R.; Laurence, S. Ontogeny of Prosocial Behavior across Diverse Societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 14586–14591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blake, P.R.; McAuliffe, K.; Corbit, J.; Callaghan, T.C.; Barry, O.; Bowie, A.; Kleutsch, L.; Kramer, K.L.; Ross, E.; Vongsachang, H.; et al. The Ontogeny of Fairness in Seven Societies. Nature 2015, 528, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoBue, V.; Nishida, T.; Chiong, C.; DeLoache, J.S.; Haidt, J. When Getting Something Good Is Bad: Even Three-Year-Olds React to Inequality: Children’s Reactions to Inequality. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Bernhard, H.; Rockenbach, B. Egalitarianism in Young Children. Nature 2008, 454, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fehr, E.; Glätzle-Rützler, D.; Sutter, M. The Development of Egalitarianism, Altruism, Spite and Parochialism in Childhood and Adolescence. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2013, 64, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutter, M. Outcomes versus Intentions: On the Nature of Fair Behavior and Its Development with Age. J. Econ. Psychol. 2007, 28, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinbeis, N.; Bernhardt, B.C.; Singer, T. Impulse Control and Underlying Functions of the Left DLPFC Mediate Age-Related and Age-Independent Individual Differences in Strategic Social Behavior. Neuron 2012, 73, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luengo Kanacri, B.P.; Pastorelli, C.; Eisenberg, N.; Zuffianò, A.; Caprara, G.V. The Development of Prosociality from Adolescence to Early Adulthood: The Role of Effortful Control: Prosociality and Effortful Control. J. Pers. 2013, 81, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlert, A.; Kindschi, M.; Algesheimer, R.; Rauhut, H. Human Social Preferences Cluster and Spread in the Field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22787–22792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 646–718. ISBN 0-471-27290-6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; De Bruin, E.M.N.; Otten, W.; Joireman, J.A. Development of Prosocial, Individualistic, and Competitive Orientations: Theory and Preliminary Evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Yamagishi, T.; Li, Y.; Kiyonari, T. Prosocial Behavior Increases with Age across Five Economic Games. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Roig, M.; Gracia-Lázaro, C.; Perelló, J.; Moreno, Y.; Sánchez, A. Transition from Reciprocal Cooperation to Persistent Behaviour in Social Dilemmas at the End of Adolescence. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Assem, M.J.; van Dolder, D.; Thaler, R.H. Split or Steal? Cooperative Behavior When the Stakes Are Large. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carpenter, J.P.; Daniere, A.G.; Takahashi, L.M. Cooperation, Trust, and Social Capital in Southeast Asian Urban Slums. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 55, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Love, A. Characteristics Affecting Charitable Donations: Empirical Evidence from Britain. J. Mark. Pract. Appl. Mark. Sci. 1997, 3, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Meier, S. Pro-Social Behavior in a Natural Setting. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 54, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. Who Gives? A Literature Review of Predictors of Charitable Giving Part One: Religion, Education, Age and Socialisation. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2011, 2, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landry, C.E.; Lange, A.; List, J.A.; Price, M.K.; Rupp, N.G. Toward an Understanding of the Economics of Charity: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2006, 121, 747–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellemare, C.; Krger, S.; van Soest, A. Measuring Inequity Aversion in a Heterogeneous Population Using Experimental Decisions and Subjective Probabilities. Econometrica 2008, 76, 815–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messick, D.M.; McClintock, C.G. Motivational Bases of Choice in Experimental Games. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.O.; Ackermann, K.A.; Handgraaf, M.J. Measuring Social Value Orientation. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2011, 6, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böhm, R.; Fleiß, J.; Rybnicek, R. On the Stability of Social Preferences in Inter-Group Conflict: A Lab-in-the-Field Panel Study. J. Confl. Resolut. 2021, 65, 1215–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, J.L.; Balliet, D.; Joireman, J.; Kuhlman, D.M.; Voelpel, S.C.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Back, M. Social Value Orientation, Expectations, and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas: A Meta–Analysis. Eur. J. Personal. 2018, 32, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Höglinger, M.; Wehrli, S. Measuring Social Preferences on Amazon Mechanical Turk. In Social Dilemmas, Institutions, and the Evolution of Cooperation; Jann, B., Przepiorka, W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-3-11-047297-4. [Google Scholar]

- Belfield, C.R.; Beney, A.P. What Determines Alumni Generosity? Evidence for the UK. Educ. Econ. 2000, 8, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Connolly, C.; Myers, C.K. Altruistic Behavior in a Representative Dictator Experiment. Exp. Econ. 2008, 11, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.A. Young, Selfish and Male: Field Evidence of Social Preferences. Econ. J. 2004, 114, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fülöp, M.; Gordon Győri, J. Japanese Students’ Perceptions of the Role That Shadow Education Plays in Competition in Education. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 11, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeTendre, G. Youth and Schooling in Japan: Competition with Peers. Berkeley J. Sociol. 1996, 41, 103–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Cooperative Behavior Cascades in Human Social Networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5334–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henrich, J.; Boyd, R.; Bowles, S.; Camerer, C.; Fehr, E.; Gintis, H.; McElreath, R.; Alvard, M.; Barr, A.; Ensminger, J.; et al. “Economic Man” in Cross-Cultural Perspective: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-Scale Societies. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28, 795–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soubelet, A.; Salthouse, T.A. Influence of Social Desirability on Age Differences in Self-Reports of Mood and Personality: Social Desirability, Age, and Self-Reports. J. Pers. 2011, 79, 741–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, W.; Smit, J.H.; Comijs, H.C. Using Social Desirability Scales in Research among the Elderly. Qual. Quant. 2001, 35, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J.J. Lie Scales and the Elderly. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1988, 9, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World; United Nations (Ed.) World Social Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-92-1-130392-6. [Google Scholar]

- Global Wage Report, 2016/17: Wage Policies in Times of Crisis; International Labour Office (Ed.) International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-2-130928-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus, B. Inequalities and Poverty Risks in Old Age across Europe: The Double-edged Income Effect of Pension Systems. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindschi, M.; Cieciuch, J.; Davidov, E.; Ehlert, A.; Rauhut, H.; Tessone, C.J.; Algesheimer, R. Values in Adolescent Friendship Networks. Netw. Sci. 2019, 7, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Jacklin, C.N. Gender Segregation in Childhood. In Advances in Child Development and Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987; Volume 20, pp. 239–287. ISBN 978-0-12-009720-3. [Google Scholar]

- Shrum, W.; Cheek, N.H.; Hunter, S.M. Friendship in School: Gender and Racial Homophily. Sociol. Educ. 1988, 61, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachlin, H.; Jones, B.A. Altruism among Relatives and Non-Relatives. Behav. Processes 2008, 79, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bowling, A.; Stafford, M. How Do Objective and Subjective Assessments of Neighbourhood Influence Social and Physical Functioning in Older Age? Findings from a British Survey of Ageing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2533–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, L.M.; McLanahan, S.S.; Garfinkel, I. The Gender-Poverty Gap: What We Can Learn from Other Countries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1994, 59, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.C.; Grossman, P.J. Are Women Less Selfish Than Men?: Evidence From Dictator Experiments. Econ. J. 1998, 108, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.A.; Giménez-Nadal, J.I.; Cuesta, J.A.; Gracia-Lazaro, C.; Moreno, Y.; Sanchez, A. Gender Differences in Cooperation: Experimental Evidence on High School Students. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heilman, R.M.; Kusev, P. Personal Values Associated with Prosocial Decisions. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Croson, R.; Gneezy, U. Gender Differences in Preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Gender | ||

|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |

| Ave. SVO | 26.34 | 23.09 |

| Altruists | 3.3 | 4.5 |

| Prosocials | 67.5 | 59.1 |

| Individualists | 27.5 | 31.5 |

| Competitors | 1.7 | 5 |

| Ehlert et al. (2020) | Age Categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11–15 Years 1 | 16–25 Years | 26–35 Years | 36–45 Years | 46–55 Years | 56–65 Years | 65+ | |

| Ave. SVO | 30.93 | 28.74 | 27.14 | 23.86 | 23.41 | 24.39 | 22.81 |

| Altruists | 0.7 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 3 | 5.3 |

| Prosocials | 79 | 64.4 | 66.7 | 59.7 | 58.3 | 71.1 | 60.5 |

| Individualists | 19.9 | 27.4 | 30 | 35.3 | 31.7 | 23 | 28.9 |

| Competitors | 0.4 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 5 | 3 | 5.3 |

| Covariates | Models | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-Up | |||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | |

| Age 1 | −0.117 ** | −0.172 *** | −0.120 ** | −0.176 *** | −0.178 ** | −0.115 ** | −0.184 ** |

| (0.037) | (0.050) | (0.037) | (0.050) | (0.056) | (0.042) | (0.057) | |

| Male | −2.331 * | −2.420 * | −2.167 † | −2.256 † | −2.014 | −1.819 | −2.023 |

| (1.166) | (1.166) | (1.165) | (1.165) | (1.257) | (1.257) | (1.260) | |

| Education | 1.506 ** | 1.466 ** | 1.306 ** | 1.270 ** | 1.103 * | 1.096 * | 1.032 † |

| (0.472) | (0.472) | (0.478) | (0.478) | (0.519) | (0.531) | (0.531) | |

| Male × Age 1 | 0.120 † | 0.122 † | 0.146 † | 0.147 † | |||

| (0.073) | (0.072) | (0.081) | (0.081) | ||||

| City size 2 | 0.138 | 0.136 | 0.221 | 0.213 | 0.245 | ||

| (0.349) | (0.349) | (0.376) | (0.378) | (0.378) | |||

| Immigrated | 0.758 | 0.549 | 2.047 | 2.425 | 2.058 | ||

| (3.608) | (3.605) | (3.939) | (3.946) | (3.944) | |||

| Political orientation 3: (ref. planned voting for independent candidate VdB) | Right-wing party voter | −3.588 ** | −3.556 ** | −4.248 ** | −4.208 ** | −4.135 ** | |

| (1.332) | (1.330) | (1.436) | (1.454) | (1.452) | |||

| Undecided voter | 0.609 | 0.761 | −1.313 | −1.600 | −1.370 | ||

| (1.847) | (1.847) | (2.017) | (2.021) | (2.021) | |||

| Non-voter | −0.937 | −0.926 | −2.663 | −2.623 | −2.541 | ||

| (1.977) | (1.974) | (2.148) | (2.161) | (2.157) | |||

| Unemployed | −0.211 | −0.269 | |||||

| (1.965) | (1.961) | ||||||

| Life satisfaction | 0.175 | 0.185 | |||||

| (0.249) | (0.248) | ||||||

| Constant | 21.819 *** | 21.776 *** | 23.369 *** | 23.288 *** | 24.042 *** | 22.899 *** | 22.728 *** |

| (1.550) | (1.548) | (2.052) | (2.050) | (2.240) | (3.020) | (3.016) | |

| Obs. | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 591 | 591 | 591 |

| R2 | 0.036 | 0.040 | 0.050 | 0.054 | 0.052 | 0.047 | 0.053 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.039 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.035 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ehlert, A.; Böhm, R.; Fleiß, J.; Rauhut, H.; Rybnicek, R.; Winter, F. The Development of Prosociality: Evidence for a Negative Association between Age and Prosocial Value Orientation from a Representative Sample in Austria. Games 2021, 12, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/g12030067

Ehlert A, Böhm R, Fleiß J, Rauhut H, Rybnicek R, Winter F. The Development of Prosociality: Evidence for a Negative Association between Age and Prosocial Value Orientation from a Representative Sample in Austria. Games. 2021; 12(3):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/g12030067

Chicago/Turabian StyleEhlert, Alexander, Robert Böhm, Jürgen Fleiß, Heiko Rauhut, Robert Rybnicek, and Fabian Winter. 2021. "The Development of Prosociality: Evidence for a Negative Association between Age and Prosocial Value Orientation from a Representative Sample in Austria" Games 12, no. 3: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/g12030067

APA StyleEhlert, A., Böhm, R., Fleiß, J., Rauhut, H., Rybnicek, R., & Winter, F. (2021). The Development of Prosociality: Evidence for a Negative Association between Age and Prosocial Value Orientation from a Representative Sample in Austria. Games, 12(3), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/g12030067