C-CTX1 and 17-OH-C-CTX1 Accumulation in Muscle and Liver of Dusky Grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe 1834): A Unique Experimental Study Under Low-Level Exposure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

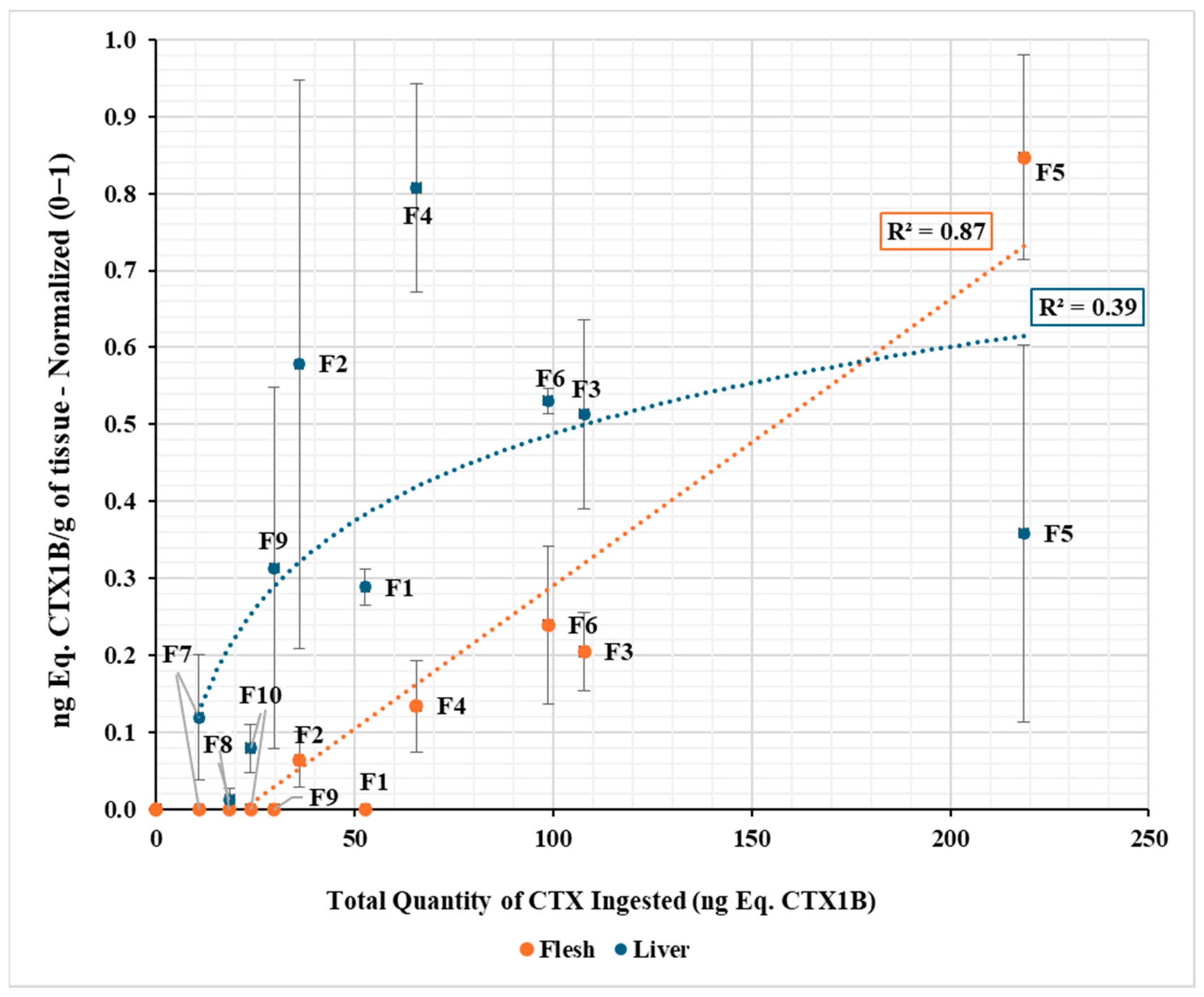

2.1. CTX Accumulation in Muscle and Liver Tissues (by CBA)

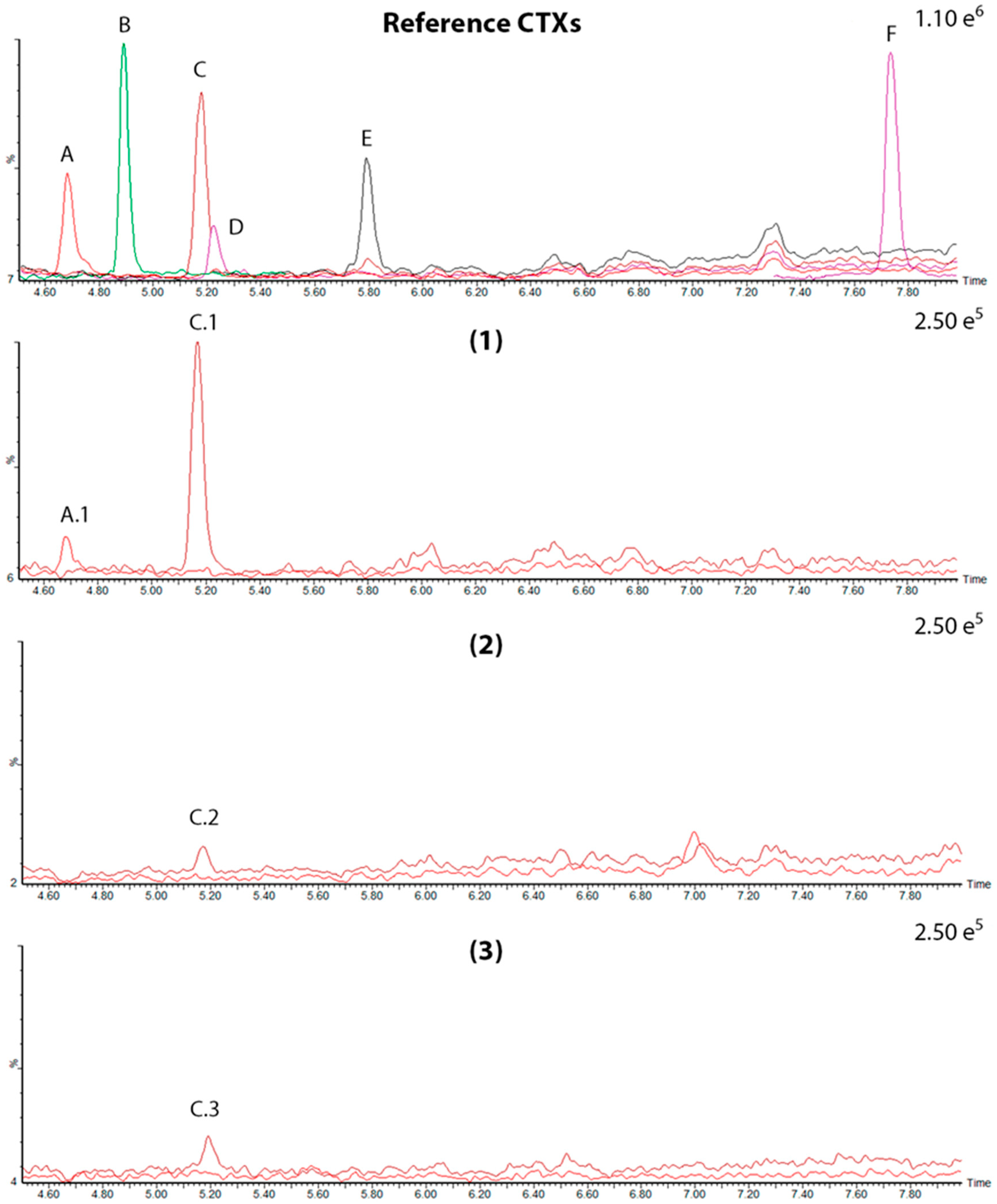

2.2. LC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Fish, Experimental Design, and Maintenance Conditions

5.2. Food Preparation and Ciguatoxin Dietary Exposure

5.3. Reagents and Standard Solutions

5.4. Extraction of CTXs

5.5. Clean-Up Procedures

5.6. Neuro-2a Cell-Based Assay for CTX Determination

5.7. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis (LC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS)

5.8. Data and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vernoux, J.P.; Lewis, R.J. Isolation and Characterisation of Caribbean Ciguatoxins from the Horse-Eye Jack (Caranx latus). Toxicon 1997, 35, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; WHO. Report of the Expert Meeting on Ciguatera Poisoning: Rome, 19–23 November 2018; Food Safety and Quality No. 9; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.; Fraga, S.; Ramilo, I.; Rial, P.; Figueroa, R.I.; Riobó, P.; Bravo, I. Canary Islands (NE Atlantic) as a Biodiversity ‘Hotspot’ of Gambierdiscus: Implications for Future Trends of Ciguatera in the Area. Harmful Algae 2017, 67, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, P.A.; Rhodes, L.L.; Smith, K.F.; Harwood, D.T.; Halafihi, T.; Marsden, I.D. Diversity and Distribution of Benthic Dinoflagellates in Tonga Include the Potentially Harmful Genera Gambierdiscus and Fukuyoa. Harmful Algae 2023, 130, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EU) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627—Of 15 March 2019 on Official Controls and Other Official Activities Performed to Ensure the Application of Food and Feed Law, Rules on Animal Health and Welfare, Plant Health and Plant Protection Product. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 1–50. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32019R0627 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain. Scientific Opinion on Marine Biotoxins in Shellfish—Emerging Toxins: Ciguatoxin Group. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Appendix 5: FDA and EPA Safety Levels in Regulations and Guidance to Safety Attributes of Fish and Fishery Products. 2021; 402, pp. 439–442. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/80400/download (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Varela Martínez, C.; León Gómez, I.; Martínez Sánchez, E.V.; Carmona Alférez, R.; Nuñez Gallo, D.; Friedemann, M.; Oleastro, M.; Boziaris, I. Incidence and Epidemiological Characteristics of Ciguatera Cases in Europe. EFSA Support. Publ. 2021, 18, EN-6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Code of Practice for the Prevention and Reduction of Ciguatera Poisoning. Codex Alimentarius International Food Standards; 2024; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/cmsgob2/export/sites/pesca/galerias/doc/Veterinario/Guia-Protocolo-Ciguat.-y-Exoticas-Rev.8-202505.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Directorate General of Public Health of the Canary Government (DG of Public Health of the Canary Government). Intoxicación Alimentaria Por Ciguatoxinas. Brotes y Casos Registrados Por El SVEICC* Según Fecha, Isla, Especie y Peso de Pescado Implicada y Confirmación de Presencia de Toxina, Canarias, 2008–2022. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/zh/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXC%2B83-2024%252FCXC_083e.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Pérez-Arellano, J.L.; Luzardo, O.P.; Brito, A.P.; Cabrera, M.H.; Zumbado, M.; Carranza, C.; Angel-Moreno, A.; Dickey, R.W.; Boada, L.D. Ciguatera Fish Poisoning, Canary Islands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.A.; Fernandez, M.; Backer, L.C.; Dickey, R.W.; Bernstein, J.; Schrank, K.; Kibler, S.; Stephan, W.; Gribble, M.O.; Bienfang, P.; et al. An Updated Review of Ciguatera Fish Poisoning: Clinical, Epidemiological, Environmental, and Public Health Management. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, G.M.; Lewis, R.J. Ciguatoxins: Cyclic Polyether Modulators of Voltage-Gated Iion Channel Function. Mar. Drugs 2006, 4, 82–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Fisheries of the Canary Government (DG Fisheries of the Canary Government). Official Control Protocol for CTX Detection of Fish Sampled at the Authorized First Sale Points, Implemented by the Canary Government. 2025; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/cmsgobcan/export/sites/pesca/galerias/doc/Veterinario/Protocolo-Ciguatoxina-Nov-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Yasumoto, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Bagnis, R.; Randall, J.E.; Banner, A.H. Toxicity of the Surgeonfishes. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 1971, 37, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darius, H.T.; Ponton, D.; Revel, T.; Cruchet, P.; Ung, A.; Tchou Fouc, M.; Chinain, M. Ciguatera Risk Assessment in Two Toxic Sites of French Polynesia Using the Receptor-Binding Assay. Toxicon 2007, 50, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfrich, P.; Banner, A.H. Experimental Induction of Ciguatera Toxicity in Fish through Diet. Nature 1963, 197, 1025–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davin, W.T.; Kohler, C.C.; Tindall, D.R. Effects of Ciguatera Toxins on the Bluehead. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1986, 115, 908–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davin, W.T.; Kohler, C.C.; Tindall, D.R. Ciguatera Toxins Adversely Affect Piscivorous Fishes. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1988, 117, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledreux, A.; Brand, H.; Chinain, M.; Bottein, M.Y.D.; Ramsdell, J.S. Dynamics of Ciguatoxins from Gambierdiscus polynesiensis in the Benthic Herbivore Mugil Cephalus: Trophic Transfer Implications. Harmful Algae 2014, 39, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J.; Holmes, M.J. Origin and Transfer of Toxins Involved in Ciguatera. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 1993, 106, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, T.; Kuniyoshi, K.; Oshiro, N.; Yasumoto, T. Biooxidation of Ciguatoxins Leads to Species-Specific Toxin Profiles. Toxins 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, E.M.; Miles, C.O.; Ivanova, L.; Uhlig, S.; James, K.S.; Erdner, D.L.; Fæste, C.K.; McCarron, P.; Robertson, A. Algal Ciguatoxin Identified as Source of Ciguatera Poisoning in the Caribbean. Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliño, L.; Costa, P.R. Global Impact of Ciguatoxins and Ciguatera Fish Poisoning on Fish, Fisheries and Consumers. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, T.; Sano, M.; Kurokura, H. Groupers of the World (Family Serranidae, Subfamily Epinephelinae). An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of the Grouper, Rockcod, Hind, Coral Grouper and Lyretail Species Known to Date. FAO Species Cat. 1993, 16, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadovy de Mitcheson, Y.; Craig, M.T.; Bertoncini, A.A.; Carpenter, K.E.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Choat, J.H.; Cornish, A.S.; Fennessy, S.T.; Ferreira, B.P.; Heemstra, P.C.; et al. Fishing Groupers towards Extinction: A Global Assessment of Threats and Extinction Risks in a Billion Dollar Fishery. Fish. Fish. 2013, 14, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.; Pascual, P.J.; Falcón, J.M.; Sancho, A.; González, G. Peces de las Islas Canarias: Catálogo Comentado e Ilustrado; Francisco Lemus: La Laguna, Spain, 2002; ISBN 84-87973-16-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Filho, J.A.; Araújo, B.C.; Mello, P.H.; Garcia, C.E.O.; Silva, V.F.D.; Li, W.; Levavi-Sivan, B.; Moreira, R.G. Hormonal Profile during the Reproductive Cycle and Induced Breeding of the Dusky Grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Teleostei: Serranidae) in Captivity. Aquaculture 2023, 566, 739150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aceituno, A.; Falcón García, I.; Torres Lana, Á.; Martín León, F.M.; Ramos-Sosa, M.J.; Sanchez-Henao, A.; Varela Martínez, C.; Negrín Díaz, M.I.; Larumbe-Zabala, E.; Cabrera García, J.U.; et al. First report in two decades of ciguatera fish poisoning linked to small-sized fish consumption in the Canary Islands. J. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 60, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Henao, A.; García-Álvarez, N.; Silva Sergent, F.; Estévez, P.; Gago-Martínez, A.; Martín, F.; Ramos-Sosa, M.; Fernández, A.; Diogène, J.; Real, F. Presence of CTXs in Moray Eels and Dusky Groupers in the Marine Environment of the Canary Islands. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020, 221, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Henao, A.; Real, F.; Darias-Dágfeel, Y.; García-Álvarez, N.; Diogène, J.; Rambla-Alegre, M. Comparison of Different Solid-Phase Cleanup Methods Prior to the Detection of Ciguatoxins in Fish by Cell-Based Assay and LC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 14580–14591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, F.; Boyra, A.; Fernández-Gil, C.; Tuya, F. Guía de Biodiversidad Marina de Canarias; Gobierno de Canarias: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-84-09-07360-3.

- Soliño, L.; Costa, P.R. Differential Toxin Profiles of Ciguatoxins in Marine Organisms: Chemistry, Fate and Global Distribution. Toxicon 2018, 150, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo-García, S.; Castro, D.; Lence, E.; Estévez, P.; Leão, J.M.; González-Bello, C.; Gago-Martínez, A.; Louzao, M.C.; Vale, C.; Botana, L.M. In Silico Simulations and Functional Cell Studies Evidence Similar Potency and Distinct Binding of Pacific and Caribbean Ciguatoxins. Expo. Health 2023, 15, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverté, J.; Shukla, S.; Tsumuraya, T.; Hirama, M.; Turquet, J.; Diogène, J.; Campàs, M. Analysis of Ciguatoxins in Fish with a Single-Step Sandwich Immunoassay. Harmful Algae 2025, 146, 102869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, G.S.; Papiol, G.G.; Rhodes, L.L.; Harwood, D.T.; Selwood, A.; Jerrett, A.; Murray, S.A.; Neilan, B.A. A Feeding Study to Probe the Uptake of Maitotoxin by Snapper (Pagrus auratus). Harmful Algae 2014, 37, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Henao, A.; García-Álvarez, N.; Padilla, D.; Ramos-Sosa, M.; Sergent, F.S.; Fernández, A.; Estévez, P.; Gago-Martínez, A.; Diogène, J.; Real, F. Accumulation of C-Ctx1 in Muscle Tissue of Goldfish (Carassius auratus) by Dietary Experience. Animals 2021, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, I.D.P.; Sdiri, K.; Taylor, A.; Viallon, J.; Ben Gharbia, H.; Mafra Júnior, L.L.; Swarzenski, P.; Oberhaensli, F.; Darius, H.T.; Chinain, M.; et al. Experimental Evidence of Ciguatoxin Accumulation and Depuration in Carnivorous Lionfish. Toxins 2021, 13, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerez, S. Efecto de Diferentes Condiciones de Cultivo En El Engorde de Meros (Epinephelus marginatus) Nacidos En Cautividad En Las Islas Canarias. In Proceedings of the Congreso Nacional de Acuicultura, Cádiz, Spain, 21–24 November 2022; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10261/313007 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kramer, M.; Font, E. Reducing Sample Size in Experiments with Animals: Historical Controls and Related Strategies. Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Mak, M.Y.L.; Cheng, J.; Li, J.; Gu, J.R.; Leung, P.T.Y.; Lam, P.K.S. Effects of dietary exposure to ciguatoxin P-CTX-1 on the reproductive performance in marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 152, 110837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mak, Y.L.; Chang, Y.H.; Xiao, C.; Chen, Y.M.; Shen, J.; Wang, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Lam, P.K.S. Uptake and Depuration Kinetics of Pacific Ciguatoxins in Orange-Spotted Grouper (Epinephelus coioides). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 4475–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Sosa, M.J.; García-Álvarez, N.; Sanchez-Henao, A.; Sergent, F.S.; Padilla, D.; Estévez, P.; Caballero, M.J.; Martín-Barrasa, J.L.; Gago-Martínez, A.; Diogène, J.; et al. Ciguatoxin Detection in Flesh and Liver of Relevant Fish Species from the Canary Islands. Toxins 2022, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, R.J.; Losen, B.; Oberhaensli, F.R.; Darius, H.T.; Sibat, M.; Hess, P.; Swarzenski, P.W.; Chinain, M.; Dechraoui Bottein, M.Y. Experimental Evidence of Dietary Ciguatoxin Accumulation in an Herbivorous Coral Reef Fish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 200, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, R.J.; Ben Gharbia, H.; Sdiri, K.; Sibat, M.; Rañada-Mestizo, M.L.; Lavenu, L.; Hess, P.; Chinain, M.; Bottein, M.Y.D. Tissue Distribution and Metabolization of Ciguatoxins in an Herbivorous Fish Following Experimental Dietary Exposure to Gambierdiscus polynesiensis. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.T.; Robertson, A. Depuration Kinetics and Growth Dilution of Caribbean Ciguatoxin in the Omnivore Lagodon rhomboides: Implications for Trophic Transfer and Ciguatera Risk. Toxins 2021, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchereau, J.L.; Body, P.; Chauvet, C. Growth of the Dusky Grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Linnnaeus, 1758) (Teleostei, Serranidae), in the Natural Marine Reserve of Lavezzi Islands, Corsica, France. Sci. Mar. 1999, 63, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinn, J.K.; Uhlig, S.; Ivanova, L.; Faeste, C.K.; Kryuchkov, F.; Robertson, A. In Vitro Glucuronidation of Caribbean Ciguatoxins in Fish: First Report of Conjugative Ciguatoxin Metabolites. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 1910–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottier, I.; Lewis, R.J.; Vernoux, J.P. Ciguatera Fish Poisoning in the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean: Reconciling the Multiplicity of Ciguatoxins and Analytical Chemistry Approach for Public Health Safety. Toxins 2023, 15, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.J.; Venables, B.; Lewis, R.J. Critical Review and Conceptual and Quantitative Models for the Transfer and Depuration of Ciguatoxins in Fishes. Toxins 2021, 13, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.J.; Lewis, R.J. A General Food Chain Model for Bioaccumulation of Ciguatoxin into Herbivorous Fish in the Pacific Ocean Suggests Few Gambierdiscus Species Can Produce Poisonous Herbivores, and Even Fewer Can Produce Poisonous Higher Trophic Level Fish. Toxins 2025, 17, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, P.; Oses-Prieto, J.; Castro, D.; Penin, A.; Burlingame, A.; Gago-Martinez, A. First Detection of Algal Caribbean Ciguatoxin in Amberjack Causing Ciguatera Poisoning in the Canary Islands (Spain). Toxins 2024, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago-Martinez, A.; Leão, J.M.; Estevez, P.; Castro, D.; Barrios, C.; Hess, P.; Sibat, M. Characterisation of Ciguatoxins. EFSA Support. Publ. 2021, 18, 6649E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J. The Changing Face of Ciguatera. Toxicon 2001, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkassar, M.; Sanchez-Henao, A.; Reverté, J.; Barreiro, L.; Rambla-Alegre, M.; Leonardo, S.; Mandalakis, M.; Peristeraki, P.; Diogène, J.; Campàs, M. Evaluation of Toxicity Equivalency Factors of Tetrodotoxin Analogues with a Neuro-2a Cell-Based Assay and Application to Puffer Fish from Greece. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darias-Dágfeel, Y.; Sanchez-Henao, A.; Padilla, D.; Martín, M.V.; Ramos-Sosa, M.J.; Poquet, P.; Barreto, M.; Silva Sergent, F.; Jerez, S.; Real, F. Effects on Biochemical Parameters and Animal Welfare of Dusky Grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe 1834) by Feeding CTX Toxic Flesh. Animals 2024, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogi, K.; Oshiro, N.; Inafuku, Y.; Hirama, M.; Yasumoto, T. Detailed LC-MS/MS Analysis of Ciguatoxins Revealing Distinct Regional and Species Characteristics in Fish and Causative Alga from the Pacific. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 8886–8891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudó, À.; Rambla-Alegre, M.; Flores, C.; Sagristà, N.; Aguayo, P.; Reverté, L.; Campàs, M.; Gouveia, N.; Santos, C.; Andree, K.B.; et al. Identification of New CTX Analogues in Fish from the Madeira and Selvagens Archipelagos by Neuro-2a CBA and LC-HRMS. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmeyer, A.; Loeffler, C.R.; Bodi, D. Extraction and LC-MS/MS Analysis of Ciguatoxins: A Semi-Targeted Approach Designed for Fish of Unknown Origin. Toxins 2021, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, K.; Yasumoto, T. Chemiluminescent Receptor Binding Assay for Ciguatoxins and Brevetoxins Using Acridinium Brevetoxin-B2. Toxins 2019, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, A.; Eixarch, H.; de la Iglesia, P.; Rodriguez, M.; Dominguez, L.; Andree, K.B.; Diogène, J. Towards the Standardisation of the Neuroblastoma (Neuro-2a) Cell-Based Assay for Ciguatoxin-like Toxicity Detection in Fish: Application to Fish Caught in the Canary Islands. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2012, 29, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/808 of 22 March 2021 on the Performance of Analytical Methods for Residues of Pharmacologically Active Substances Used in Food-Producing Animals and on the Interpretation of Results as Well as on the Methods To. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L180, 84–109. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.S.; Passfield, E.M.F.; Rhodes, L.L.; Puddick, J.; Finch, S.C.; Smith, K.F.; van Ginkel, R.; Mudge, E.M.; Nishimura, T.; Funaki, H.; et al. Targeted Metabolite Fingerprints of Thirteen Gambierdiscus, Five Coolia and Two Fukuyoa Species. Mar Drugs 2024, 22, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group (Toxic Food) ng Eq. CTX1B/g | Week | Fish (no.) | Total Quantity of CTX Ingested a | Flesh | Liver | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-Like Toxicity ng Eq. CTX1B/g (n = 8) b | Toxin Burden c | CTXs Ingested Accumulated (%) d | CTX-Like Toxicity ng Eq. CTX1B/g (n = 4) | Toxin Burden b | Toxins Ingested Accumulated (%) c | ||||

| A 0.109 ± 0.003 | 4 | 1 | 52.69 | <LOD | 0 | 0 | 0.397 ± 0.032 | 4.85 | 9.22 |

| 2 | 36.03 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 1.02 | 2.85 | 0.782 ± 0.490 | 11.65 | 32.34 | ||

| 10 | 3 | 107.77 | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 3.74 | 3.47 | 0.715 ± 0.150 | 10.72 | 9.95 | |

| 4 | 65.53 | 0.007 ± 0.003 | 1.95 | 2.97 | 1.085 ± 0.179 | 16.21 | 24.74 | ||

| 18 | 5 | 218.48 | 0.049 ± 0.001 | 17.27 | 7.91 | 0.490 ± 0.325 | 13.48 | 6.17 | |

| 6 | 98.73 | 0.014 ± 0.006 | 2.63 | 2.66 | 0.779 ± 0.118 | 9.42 | 9.54 | ||

| B 0.015 ± 0.001 | 6 | 7 | 10.78 | <LOD | 0 | 0 | 0.057 ± 0.008 | 0.87 | 8.09 |

| 8 | 18.49 | <LOD | 0 | 0 | 0.032 ± 0.018 | 0.48 | 4.47 | ||

| 12 | 9 | 29.73 | <LOD | 0 | 0 | 0.430 ± 0.311 | 8.90 | 29.96 | |

| 10 | 23.77 | <LOD | 0 | 0 | 0.120 ± 0.041 | 2.08 | 8.78 | ||

| Group | Week | Fish (no.) | Flesh | Liver | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-CTX1 (ng) | 17-OH-CTX1 (ng) | C-CTX1 (ng) | 17-OH-CTX1 (ng) | |||

| A | 4 | 1 | - | - | 0.082 ± 0.009 | 0.014 ± 0.0011 |

| 2 | - | - | 0.071 ± 0.003 | 0.012 ± 0.0005 | ||

| 10 | 3 | - | - | 0.167 ± 0.0003 | 0.030 ± 0.0006 | |

| 4 | - | - | 0.153 ± 0.006 | 0.028 ± 0.0008 | ||

| 18 | 5 | 0.006 ± 0.0003 | - | 0.025 ± 0.002 | - | |

| 6 | - | - | 0.130 ± 0.007 | 0.018 ± 0.0014 | ||

| B | 6 | 7 | - | - | 0.020 ± 0.0003 | - |

| 8 | - | - | 0.013 ± 0.0005 | - | ||

| 12 | 9 | - | - | 0.024 ± 0.002 | - | |

| 10 | - | - | 0.015 ± 0.001 | - | ||

| Trial | Species | Tissue | Somatic Indexes (% ± SD) | Daily Intake of CTX Per g of Live Weight (pg CTX/g/d) a | Uptake Rate Per g of Tissue Eq. (pg CTX/g/d) b | Toxin Assimilation Rate Per Unit of Toxin Ingested, Corrected by Somatic Index (%) c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current experiment | E. marginatus (carnivore) | Muscle | 20.33 ± 4.19 | Group A = 1.4 | 0.29 | 4.18 |

| Liver | 1.03 ± 0.19 | Group B = 0.2 | 3.87 | 19.95 | ||

| Bennet and Robertson [46] | L. rhomboides (omnivore) | Muscle | 34.9 ± 6.78 d | 19 and 17 | 3.4 | 6.98 and 6.25 |

| Liver | 1.00 ± 0.27 d | 63 | 3.71 and 3.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Darias-Dágfeel, Y.; Sanchez-Henao, A.; Rambla-Alegre, M.; Diogène, J.; Flores, C.; Padilla, D.; Ramos-Sosa, M.J.; Poquet Blat, P.M.; Silva Sergent, F.; Jerez, S.; et al. C-CTX1 and 17-OH-C-CTX1 Accumulation in Muscle and Liver of Dusky Grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe 1834): A Unique Experimental Study Under Low-Level Exposure. Toxins 2026, 18, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010003

Darias-Dágfeel Y, Sanchez-Henao A, Rambla-Alegre M, Diogène J, Flores C, Padilla D, Ramos-Sosa MJ, Poquet Blat PM, Silva Sergent F, Jerez S, et al. C-CTX1 and 17-OH-C-CTX1 Accumulation in Muscle and Liver of Dusky Grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe 1834): A Unique Experimental Study Under Low-Level Exposure. Toxins. 2026; 18(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleDarias-Dágfeel, Yefermin, Andres Sanchez-Henao, Maria Rambla-Alegre, Jorge Diogène, Cintia Flores, Daniel Padilla, María José Ramos-Sosa, Paula María Poquet Blat, Freddy Silva Sergent, Salvador Jerez, and et al. 2026. "C-CTX1 and 17-OH-C-CTX1 Accumulation in Muscle and Liver of Dusky Grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe 1834): A Unique Experimental Study Under Low-Level Exposure" Toxins 18, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010003

APA StyleDarias-Dágfeel, Y., Sanchez-Henao, A., Rambla-Alegre, M., Diogène, J., Flores, C., Padilla, D., Ramos-Sosa, M. J., Poquet Blat, P. M., Silva Sergent, F., Jerez, S., & Real, F. (2026). C-CTX1 and 17-OH-C-CTX1 Accumulation in Muscle and Liver of Dusky Grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe 1834): A Unique Experimental Study Under Low-Level Exposure. Toxins, 18(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010003