Uses of Botulinum Toxin in Headache and Facial Pain Disorders: An Update

Abstract

1. Introduction

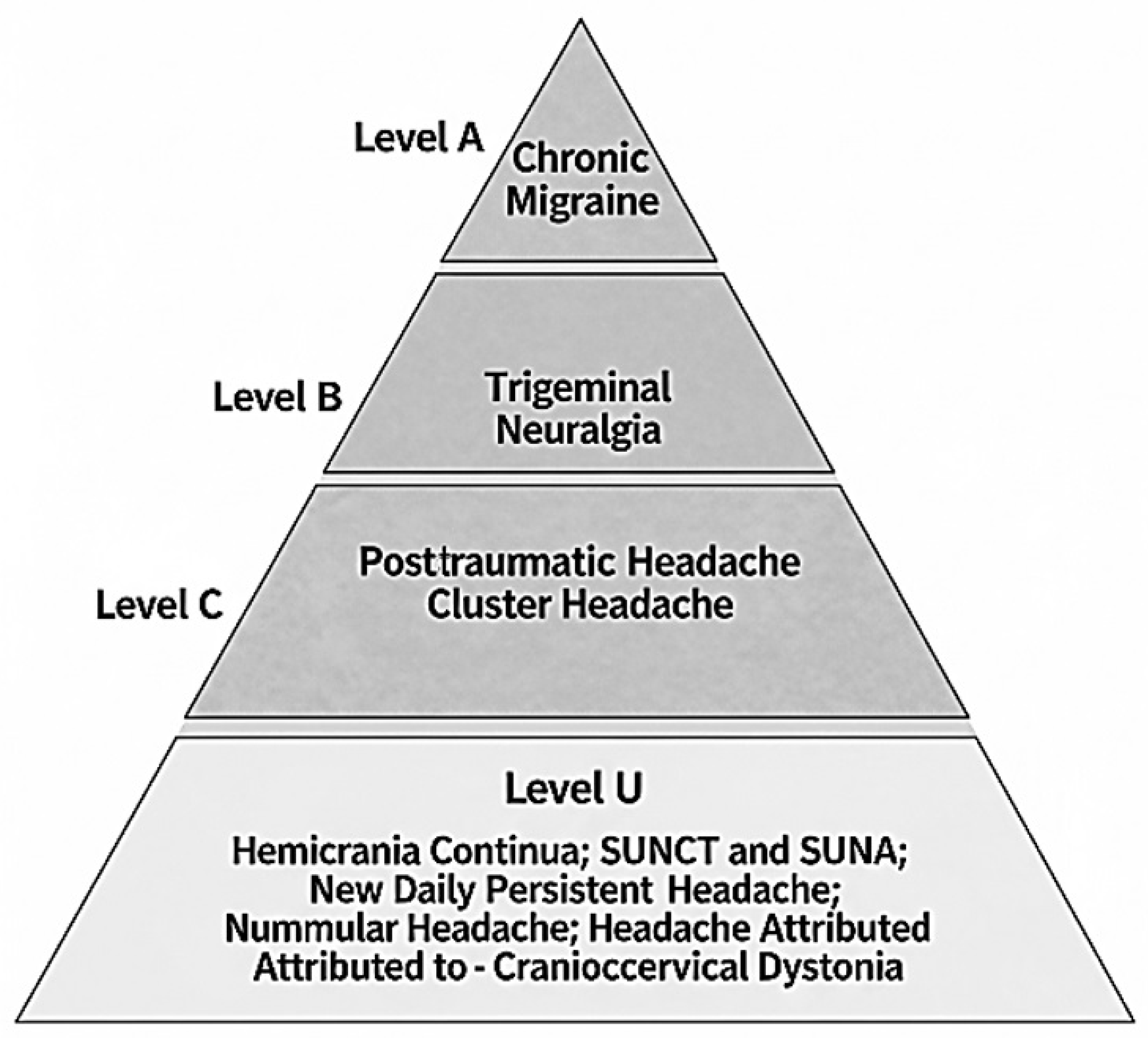

2. Method

3. Chronic Migraine

4. Cluster Headache

5. Hemicrania Continua

6. SUNCT and SUNA

7. New Daily Persistent Headache

8. Nummular Headache

9. Post-Traumatic Headache

10. Headache Attributed to Craniocervical Dystonia

11. Trigeminal Neuralgia

12. Ongoing Clinical Trials

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Onan, D.; Farham, F.; Martelletti, P. Clinical Conditions Targeted by OnabotulinumtoxinA in Different Ways in Medicine. Toxins 2024, 16, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farham, F.; Onan, D.; Martelletti, P. Non-Migraine Head Pain and Botulinum Toxin. Toxins 2024, 16, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossetto, O.; Pirazzini, M.; Montecucco, C. Botulinum Neurotoxins: Genetic, Structural and Mechanistic Insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matak, I.; Bölcskei, K.; Bach-Rojecky, L.; Helyes, Z. Mechanisms of Botulinum Toxin Type A Action on Pain. Toxins 2019, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.P.; Hvedstrup, J.; Schytz, H.W. Botulinum Toxin: A Review of the Mode of Action in Migraine. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2018, 137, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.J.; Niu, J.Q.; Chen, Y.T.; Deng, W.J.; Xu, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, W.F.; Liu, T. Unilateral Facial Injection of Botulinum Neurotoxin A Attenuates Bilateral Trigeminal Neuropathic Pain and Anxiety-like Behaviors through Inhibition of TLR2-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Mice. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovner, L.J.; Hagen, K.; Linde, M.; Steiner, T.J. The Global Prevalence of Headache: An Update, with Analysis of the Influences of Methodological Factors on Prevalence Estimates. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M.; Raggi, A. A Narrative Review on the Burden of Migraine: When the Burden Is the Impact on People’s Life. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, D.; Raggi, A.; Grazzi, L.; Lambru, G. Disability, Quality of Life, and Socioeconomic Burden of Cluster Headache: A Critical Review of Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Headache 2020, 60, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Bigal, M.E.; Kolodner, K.; Stewart, W.F.; Liberman, J.N.; Steiner, T.J. The Family Impact of Migraine: Population-Based Studies in the USA and UK. Cephalalgia 2003, 23, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, A.D.; Shah, A. National Trends in Direct Health Care Expenditures Among US Adults With Migraine: 2004 to 2013. J. Pain 2017, 18, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloudek, L.M.; Stokes, M.; Buse, D.C.; Wilcox, T.K.; Lipton, R.B.; Goadsby, P.J.; Varon, S.F.; Blumenfeld, A.M.; Katsarava, Z.; Pascual, J.; et al. Cost of Healthcare for Patients with Migraine in Five European Countries: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). J. Headache Pain 2012, 13, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.B.; Queiroz, L.P.; Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.; Sarmento, E.M.; Peres, M.F.P. Annual Indirect Costs Secondary to Headache Disability in Brazil. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.F.P.; Queiroz, L.P.; Rocha-Filho, P.S.; Sarmento, E.M.H.; Katsarava, Z.; Steiner, T.J. Migraine: A Major Debilitating Chronic Non-Communicable Disease in Brazil, Evidence from Two National Surveys. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashina, S.; Mitsikostas, D.D.; Lee, M.J.; Yamani, N.; Wang, S.J.; Messina, R.; Ashina, H.; Buse, D.C.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Jensen, R.H.; et al. Tension-Type Headache. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashina, M.; Katsarava, Z.; Do, T.P.; Buse, D.C.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Özge, A.; Krymchantowski, A.V.; Lebedeva, E.R.; Ravishankar, K.; Yu, S.; et al. Migraine: Epidemiology and Systems of Care. Lancet 2021, 397, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashina, S.; Robertson, C.E.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Di Stefano, G.; Donnet, A.; Hodaie, M.; Obermann, M.; Romero-Reyes, M.; Park, Y.S.; Cruccu, G.; et al. Trigeminal Neuralgia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Jensen, R.; Uluduz, D.; Katsarava, Z. Migraine Remains Second among the World’s Causes of Disability, and First among Young Women: Findings from GBD2019. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Alahdab, F.; Amit, A.M.L.; Bärnighausen, T.W.; Beghi, E.; Beheshti, M.; Chavan, P.P.; Criqui, M.H.; Desai, R.; et al. Burden of Neurological Disorders Across the US From 1990-2017: A Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Viktrup, L.; Nicholson, R.A.; Ossipov, M.H.; Vargas, B.B. The Not so Hidden Impact of Interictal Burden in Migraine: A Narrative Review. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1032103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.A.; Gherpelli, J.L.D. Premonitory and Accompanying Symptoms in Childhood Migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2022, 26, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.M.; Lyngberg, A.; Jensen, R.H. Burden of Cluster Headache. Cephalalgia 2007, 27, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurora, S.K.; Dodick, D.W.; Turkel, C.C.; Degryse, R.E.; Silberstein, S.D.; Lipton, R.B.; Diener, H.C.; Brin, M.F. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Chronic Migraine: Results from the Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase of the PREEMPT 1 Trial. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, H.C.; Dodick, D.W.; Aurora, S.K.; Turkel, C.C.; Degryse, R.E.; Lipton, R.B.; Silberstein, S.D.; Brin, M.F. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Chronic Migraine: Results from the Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase of the PREEMPT 2 Trial. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampl, C.; Rudolph, M.; Bräutigam, E. OnabotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Refractory Chronic Cluster Headache. J. Headache Pain 2018, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratbak, D.F.; Nordgård, S.; Stovner, L.J.; Linde, M.; Folvik, M.; Bugten, V.; Tronvik, E. Pilot Study of Sphenopalatine Injection of OnabotulinumtoxinA for the Treatment of Intractable Chronic Cluster Headache. Cephalalgia 2016, 36, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Correia, F.; Lagrata, S.; Matharu, M.S. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Hemicrania Continua: Open Label Experience in 9 Patients. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lian, Y.J.; Ma, Y.Q.; Xie, N.C.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, L. Botulinum Toxin A for the Treatment of a Child with SUNCT Syndrome. Pain Res. Manag. 2016, 2016, 8016065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lian, Y. Sustained Response to Botulinum Toxin Type A in SUNA Sydrome. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalza, R.J. Sustained Response to Botulinum Toxin in SUNCT Syndrome. Cephalalgia 2012, 32, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Kriegler, J.; Tepper, S.; Vij, B. New Daily Persistent Headache and OnabotulinumtoxinA Therapy. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 42, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Azorín, D.; Trigo-López, J.; Sierra, Á.; Blanco-García, L.; Martínez-Pías, E.; Martínez, B.; Talavera, B.; Guerrero, Á.L. Observational, Open-Label, Non-Randomized Study on the Efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Nummular Headache: The Pre-Numabot Study. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirovich, M.D.; Pangarkar, S.S.; Manh, C.; Chen, L.; Vangala, S.; Elashoff, D.A.; Izuchukwu, I.S. Botulinum Toxin Type A for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Headache: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-over Study. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugenio Ramalho Bezerra, M.; Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.A. Headache Attributed to Craniocervical Dystonia: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, H.S.; El-Tamawy, M.S.; Shalaby, N.M.; Ramzy, G. Botulinum Toxin-Type A: Could It Be an Effective Treatment Option in Intractable Trigeminal Neuralgia? J. Headache Pain 2013, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, C.; Piedimonte, F.; Díaz, S.; Micheli, F. Acute Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia with Onabotulinum Toxin A. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 36, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.J.; Lian, Y.J.; Zheng, Y.K.; Zhang, H.F.; Chen, Y.; Xie, N.C.; Wang, L.J. Botulinum Toxin Type A for the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Cephalalgia 2012, 32, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lian, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, C.; Xie, N.; Wu, C. Two Doses of Botulinum Toxin Type A for the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: Observation of Therapeutic Effect from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Headache Pain 2014, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appendix C: AAN Classification of Evidence for the Rating of a Therapeutic Study. Continuum 2015, 21, 1169. [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd Edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurora, S.K.; Winner, P.; Freeman, M.C.; Spierings, E.L.; Heiring, J.O.; Degryse, R.E.; Vandenburgh, A.M.; Nolan, M.E.; Turkel, C.C. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Chronic Migraine: Pooled Analyses of the 56-Week PREEMPT Clinical Program. Headache 2011, 51, 1358–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herd, C.P.; Tomlinson, C.L.; Rick, C.; Scotton, W.J.; Edwards, J.; Ives, N.J.; Clarke, C.E.; Sinclair, A.J. Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Botulinum Toxin for the Prevention of Migraine. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanteri-Minet, M.; Ducros, A.; Francois, C.; Olewinska, E.; Nikodem, M.; Dupont-Benjamin, L. Effectiveness of OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) for the Preventive Treatment of Chronic Migraine: A Meta-Analysis on 10 Years of Real-World Data. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1543–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornello, R.; Ahmed, F.; Negro, A.; Miscio, A.M.; Santoro, A.; Alpuente, A.; Russo, A.; Silvestro, M.; Cevoli, S.; Brunelli, N.; et al. Is There a Gender Difference in the Response to OnabotulinumtoxinA in Chronic Migraine? Insights from a Real-Life European Multicenter Study on 2879 Patients. Pain Ther. 2021, 10, 1605–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornello, R.; Baraldi, C.; Ahmed, F.; Negro, A.; Miscio, A.M.; Santoro, A.; Alpuente, A.; Russo, A.; Silvestro, M.; Cevoli, S.; et al. Excellent Response to OnabotulinumtoxinA: Different Definitions, Different Predictors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamura, C.; Ornello, R.; Ahmed, F.; Negro, A.; Miscio, A.M.; Santoro, A.; Alpuente, A.; Russo, A.; Silvestro, M.; Cevoli, S.; et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA in Elderly Patients with Chronic Migraine: Insights from a Real-Life European Multicenter Study. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.; Kalifa, A.; Kuziek, J.; Kabbouche, M.; Hershey, A.D.; Orr, S.L. The Safety and Efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA Injections for Children and Adolescents with Chronic Migraine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Headache 2024, 64, 1200–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, P.K.; Kabbouche, M.; Yonker, M.; Wangsadipura, V.; Lum, A.; Brin, M.F. A Randomized Trial to Evaluate OnabotulinumtoxinA for Prevention of Headaches in Adolescents With Chronic Migraine. Headache 2020, 60, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, M.F.; Kirby, R.S.; Slavotinek, A.; Adams, A.M.; Parker, L.; Ukah, A.; Radulian, L.; Elmore, M.R.P.; Yedigarova, L.; Yushmanova, I. Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients Exposed to OnabotulinumtoxinA Treatment: A Cumulative 29-Year Safety Update. Neurology 2023, 101, E103–E113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.T.; Khan, R.; Buture, A.; Khalil, M.; Ahmed, F. OnabotulinumtoxinA Treatment for Chronic Migraine in Pregnancy: An Updated Report of Real-World Headache and Pregnancy Outcomes over 14 Years in Hull. Cephalalgia 2025, 45, 3331024251327387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puledda, F.; Sacco, S.; Diener, H.-C.; Ashina, M.; Al-Khazali, H.M.; Ashina, S.; Burstein, R.; Liebler, E.; Cipriani, A.; Chu, M.K.; et al. International Headache Society Global Practice Recommendations for Preventive Pharmacological Treatment of Migraine. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 3331024241269735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sostak, P.; Krause, P.; Förderreuther, S.; Reinisch, V.; Straube, A. Botulinum Toxin Type-A Therapy in Cluster Headache: An Open Study. J. Headache Pain 2007, 8, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Aschehoug, I.; Bratbak, D.F.; Tronvik, E.A. Long-Term Outcome of Patients With Intractable Chronic Cluster Headache Treated With Injection of Onabotulinum Toxin A Toward the Sphenopalatine Ganglion—An Observational Study. Headache 2018, 58, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, L.; Jamtøy, K.A.; Aschehoug, I.; Hara, S.; Meisingset, T.W.; Matharu, M.S.; Tronvik, E.; Bratbak, D.F. Open Label Experience of Repeated OnabotulinumtoxinA Injections towards the Sphenopalatine Ganglion in Patients with Chronic Cluster Headache and Chronic Migraine. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 3331024241273967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespi, J.; Bratbak, D.; Dodick, D.W.; Matharu, M.; Solheim, O.; Gulati, S.; Berntsen, E.M.; Tronvik, E. Open-Label, Multi-Dose, Pilot Safety Study of Injection of OnabotulinumtoxinA Toward the Otic Ganglion for the Treatment of Intractable Chronic Cluster Headache. Headache 2020, 60, 1632–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, I.; Cutrer, F.M. Pain Relief and Persistence of Dysautonomic Features in a Patient with Hemicrania Continua Responsive to Botulinum Toxin Type A. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Ahmed, F. Hemicrania Continua Responsive to Botulinum Toxin Type a: A Case Report. Headache 2013, 53, 831–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Mehta, D.; Ray, J.C.; Hutton, E.J.; Matharu, M.S. New Daily Persistent Headache: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cephalalgia 2023, 43, 3331024231168089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.P.; Rozen, T.D. Update in the Understanding of New Daily Persistent Headache. Cephalalgia 2023, 43, 3331024221146314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.C.L.S.; da Silva, P.A.; Rocha-Filho, P.A.S. Persistent Headache and Chronic Daily Headache after COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study. Korean J. Pain 2024, 37, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, R.C. Efficacy of Botulinum Toxin Type A in New Daily Persistent Headache. J. Headache Pain 2008, 9, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trucco, M.; Ruiz, L. P009. A Case of New Daily Persistent Headache Treated with Botulinum Toxin Type A. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, A119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cuadrado, M.L. Epicranial Headaches Part 2: Nummular Headache and Epicrania Fugax. Cephalalgia 2023, 43, 3331024221146976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Filho, P.A.S. Nummular Headache: Two Simultaneous Areas of Pain in the Same Patient. Cephalalgia 2011, 31, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, U.K.; Saleem, S.; Anwar, A.; Malik, P.; Chauhan, B.; Kapoor, A.; Arumaithurai, K.; Kavi, T. Characteristics and Treatment Effectiveness of the Nummular Headache: A Systematic Review and Analysis of 110 Cases. BMJ Neurol. Open 2020, 2, e000049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.; Bressman, S.B.; DeLong, M.R.; Fahn, S.; Fung, V.S.C.; Hallett, M.; Jankovic, J.; Jinnah, H.A.; Klein, C.; et al. Phenomenology and Classification of Dystonia: A Consensus Update. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrera-Figallo, M.A.; Ruiz-De-León-Hernández, G.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Castro-Araya, A.; Torres-Ferrerosa, O.; Hernández-Pacheco, E.; Gutierrez-Perez, J.L. Use of Botulinum Toxin in Orofacial Clinical Practice. Toxins 2020, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.E.R.; Rocha-Filho, P.A.S. Headache Attributed to Craniocervical Dystonia—A Little Known Headache. Headache 2017, 57, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Jimenez, N.; Lampuri, C.; Patino-Picirrillo, R.; Hargreave, M.J.; Hanson, M.R. Dystonia and Headaches: Clinical Features and Response to Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Adv. Neurol. 2004, 94, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Ondo, W.G.; Gollomp, S.; Galvez-Jimenez, N. A Pilot Study of Botulinum Toxin A for Headache in Cervical Dystonia. Headache 2005, 45, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowson, A.J.; Kilminster, S.G.; Salt, R. Clinical Profile of Botulinum Toxin A in Patients with Chronic Headaches and Cervical Dystonia: A Prospective, Open-Label, Longitudinal Study Conducted in a Naturalistic Clinical Practice Setting. Drugs R D 2008, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, P.K.; Sadowsky, C.H.; Martinez, W.C.; Zuniga, J.A.; Poulette, A. Concurrent Onabotulinumtoxina Treatment of Cervical Dystonia and Concomitant Migraine. Headache 2012, 52, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolin, A.; Broner, S.W.; Yoo, A.; Guan, I.; Lakhani, S.; Trabilsy, M.; Klebanoff, L.; Vo, M.; Sarva, H. Dystonia Phenomenology and Treatment Response in Migraine. Headache 2023, 63, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohluli, B.; Motamedi, M.H.K.; Bagheri, S.C.; Bayat, M.; Lassemi, E.; Navi, F.; Moharamnejad, N. Use of Botulinum Toxin A for Drug-Refractory Trigeminal Neuralgia: Preliminary Report. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2011, 111, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, J.; Bratbak, D.; Dodick, D.W.; Matharu, M.; Jamtøy, K.A.; Tronvik, E. Pilot Study of Injection of OnabotulinumtoxinA Toward the Sphenopalatine Ganglion for the Treatment of Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Headache 2019, 59, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türk, Ü.; Ilhan, S.; Alp, R.; Sur, H. Botulinum Toxin and Intractable Trigeminal Neuralgia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2005, 28, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovesan, E.J.; Teive, H.G.; Kowacs, P.A.; Della Coletta, M.V.; Werneck, L.C.; Silberstein, S.D. An Open Study of Botulinum-A Toxin Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia. Neurology 2005, 65, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tereshko, Y.; Valente, M.; Belgrado, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Dal Bello, S.; Merlino, G.; Gigli, G.L.; Lettieri, C. The Therapeutic Effect of Botulinum Toxin Type A on Trigeminal Neuralgia: Are There Any Differences between Type 1 versus Type 2 Trigeminal Neuralgia? Toxins 2023, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lian, Y.; Xie, N.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y. Single-Dose Botulinum Toxin Type a Compared with Repeated-Dose for Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Pilot Study. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lian, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.F.; Ma, Y.Q.; He, C.H.; Wu, C.J.; Xie, N.C.; Zheng, Y.K.; Zhang, Y. Therapeutic Effect of Botulinum Toxin-A in 88 Patients with Trigeminal Neuralgia with 14-Month Follow-Up. J. Headache Pain 2014, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.H.; He, C.H.; Zhang, H.F.; Lian, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.J.; Ma, Y.Q. Botulinum Toxin A in the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016, 126, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val, M.; Delcanho, R.; Ferrari, M.; Guarda Nardini, L.; Manfredini, D. Is Botulinum Toxin Effective in Treating Orofacial Neuropathic Pain Disorders? A Systematic Review. Toxins 2023, 15, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Year | Number of Participants | Study Design | Type of Botulinum Toxin | Site of Injections | Follow Up After the Intervention | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Migraine | ||||||

| Aurora et al., 2010 [23] | 679 | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 24 weeks | Greater decrease in the mean number of headache days than the placebo group. |

| Diener et al., 2010 [24] | 705 | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 24 weeks | Greater decrease in the mean number of headache days than the placebo group. |

| Chronic Cluster headache | ||||||

| Lampl et al., 2018 [25] | 12 | Open-label clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 24 weeks | Reduction in the frequency of headache days, total headache duration, and headache intensity compared to baseline. |

| Blatbak et al., 2016 [26] | 10 | Open-label clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | Sphenopalatine ganglion blockade | 24 weeks | Decrease in the frequency of headache attacks compared to baseline. |

| Hemicrania continua | ||||||

| Miller et al., 2015 [27] | 9 | Case series | Onabotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | - | Improvement in headache intensity and frequency. |

| SUNCT and SUNA | ||||||

| Zhang et al., 2016 [28] Zhang et al., 2019 [29] Zabalza, 2012 [30] | 3 | Case report | Botulinum toxin A | Subcutaneously into the area of pain | 16 to 30 months | Improvement in headache intensity and frequency. |

| New daily persistent headache | ||||||

| Ali et al., 2019 [31] | 19 | Retrospective cohort study | Abobotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 12 months | Improvement in headache intensity and frequency. |

| Nummular headache | ||||||

| García-Azorín et al., 2019 [32] | 53 | Open-label clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | Area of pain | 24 weeks | Improvement in headache intensity and frequency. |

| Post-traumatic headache | ||||||

| Zirovich et al., 2021 [33] | 40 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Abobotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 32 weeks | Greater decrease in headache intensity and frequency than the placebo group. |

| Headache attributed to craniocervical dystonia | ||||||

| Eugenio Ramalho Bezerra and Sampaio Rocha-Filho, 2020 [34] | 24 | Prospective cohort study | Abobotulinum toxin A | Dystonic muscles | 16 weeks | Decrease in headache impact. |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | ||||||

| Shehata et al., 2013 [35] | 20 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | Area of pain | 12 weeks | Greater decrease in headache intensity and frequency than the placebo group. |

| Zúñiga et al., 2013 [36] | 36 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | Area of pain | 12 weeks | Greater decrease in headache intensity than the placebo group. |

| Wu et al., 2012 [37] | 42 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Botulinum toxin A (made in Lanzhou Biological Products Institute) | Area of pain | 12 weeks | Greater decrease in headache intensity and frequency than the placebo group. |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [38] | 84 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Botulinum toxin A (made in Lanzhou Biological Products Institute) | Area of pain | 8 weeks | Greater decrease in headache intensity than the placebo group. |

| Author/Sponsor | ClinicalTrials.gov ID | Headache | Study Design | Intervention | Site of Injections | Estimated Study Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zagazig University, Egypt | NCT06684249 | Chronic migraine | Randomized controlled trial | Supratrochlear and greater occipital nerve block (local anesthetics and corticosteroids) vs. onabotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 10 July 2025 |

| Ipsen Clinical Study Enquiries | NCT06047444 | Chronic migraine | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Dysport | “muscles across the head, neck, face and shoulders.” | 21 December 2026 |

| Cairo University, Egypt | NCT06974617 | Chronic migraine | Randomized, controlled trial | Onabotulinum toxin A vs. sphenopalatine ganglion block (lidocaine) | 1 October 2025 | |

| Navy Medical Center at Camp Lejeune, United States | NCT05598723 | Chronic migraine | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial | Onabotulinum toxin A (Botox) vs. incobotulinum toxin A (Xeomin) | 24 August 2026 | |

| Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Italy | NCT06537700 | Chronic migraine | Open-label clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | 31 December 2025 | |

| Ki Health Partners. LLC. United States | NCT06154070 | Migraine | Prospective, multicenter, unblinded study | Doxibutlinum toxin A | “EEG paradigm” | October 2024 (Active, not recruiting) |

| Ipsen Clinical Study Enquiries | NCT06047457 | Episodic migraine | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Dysport | “muscles across the head, neck, face and shoulders.” | 21 December 2026 |

| Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway | NCT03944876 | Chronic cluster headache | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Botulinum toxin type A | Sphenopalatine ganglion blockade | September 2025 |

| Danish Headache Center | NCT06839118 | Post-traumatic headache | Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Onabotulinum toxin A | PREEMPT protocol | 1 August 2026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.A.; Dominguez, M.; Robinson, C.L.; Ashina, S. Uses of Botulinum Toxin in Headache and Facial Pain Disorders: An Update. Toxins 2025, 17, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17070314

Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA, Dominguez M, Robinson CL, Ashina S. Uses of Botulinum Toxin in Headache and Facial Pain Disorders: An Update. Toxins. 2025; 17(7):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17070314

Chicago/Turabian StyleSampaio Rocha-Filho, Pedro Augusto, Moises Dominguez, Christopher L. Robinson, and Sait Ashina. 2025. "Uses of Botulinum Toxin in Headache and Facial Pain Disorders: An Update" Toxins 17, no. 7: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17070314

APA StyleSampaio Rocha-Filho, P. A., Dominguez, M., Robinson, C. L., & Ashina, S. (2025). Uses of Botulinum Toxin in Headache and Facial Pain Disorders: An Update. Toxins, 17(7), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17070314