Predictive Factors for the Successful Outcome of Urethral Sphincter Injections of Botulinum Toxin A for Non-Neurogenic Dysfunctional Voiding in Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

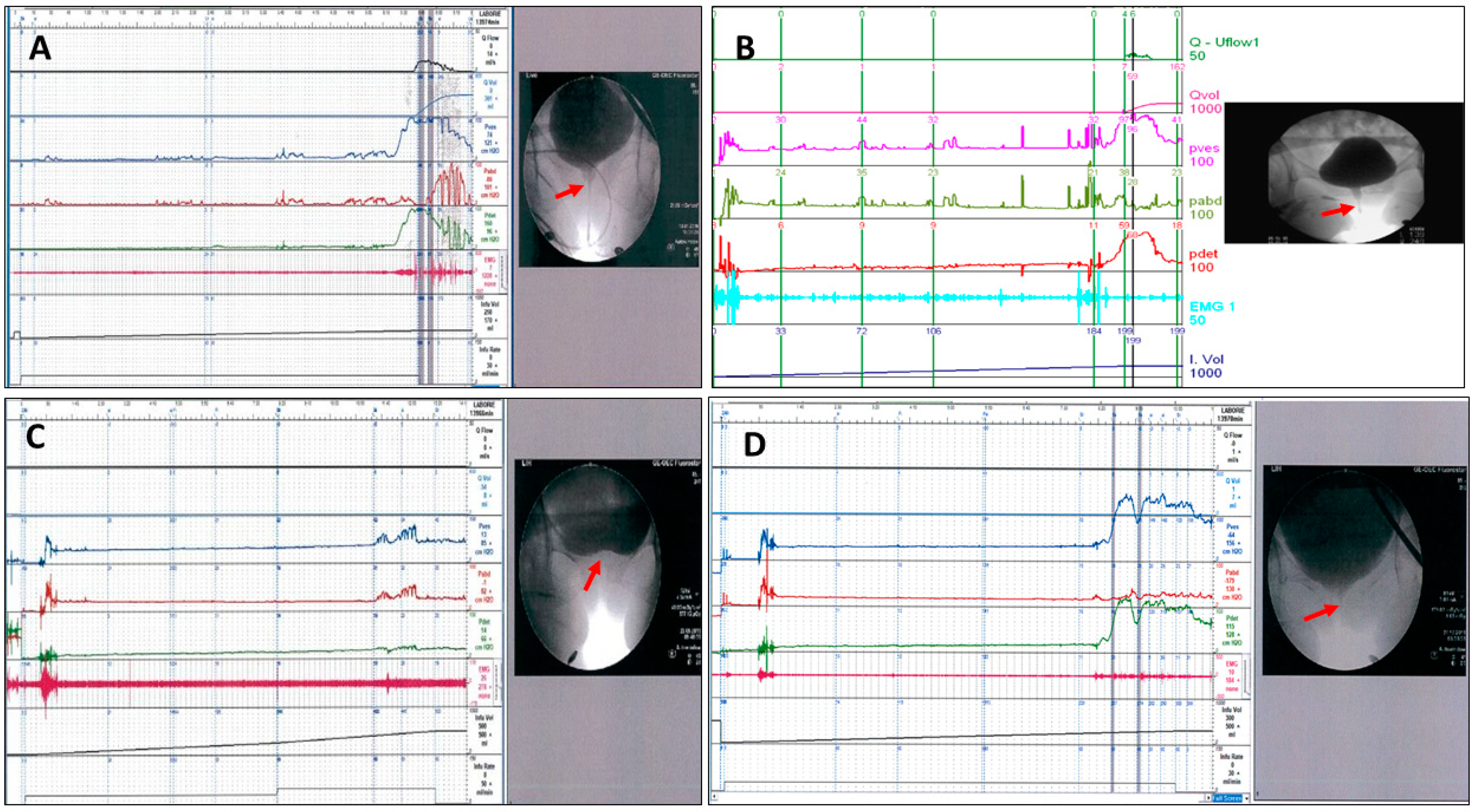

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haylen, B.T.; de Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010, 29, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, J.A.; Abrams, P.H. Obstructed voiding in the female. Br. J. Urol. 1988, 61, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitti, V.W.; Fiske, J. Cystometrogram versus cystometrogram plus voiding pressure-flow studies in women with lower urinary tract symptoms. J. Urol. 1999, 161, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groutz, A.; Blaivas, J.G.; Pies, C.; Sassone, A.M. Learned voiding dysfunction (non-neurogenic, neurogenic bladder) among adults. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2001, 20, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kim, J.C.; Lee, K.S.; Seo, J.T.; Kim, H.-J.; Yoo, T.K.; Lee, J.B.; Choo, M.-S.; Lee, J.G.; Lee, J.Y. Analysis of female voiding dysfunction: A prospective, multi-center study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2013, 45, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malde, S.; Solomon, E.; Spilotros, M.; Mukhtar, B.; Pakzad, M.; Hamid, R.; Ockrim, J.; Greenwell, T. Female bladder outlet obstruction: Common symptoms masking an uncommon cause. LUTS Low. Urin. Tract Symptoms 2019, 11, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minardi, D.; D’Anzeo, G.; Parri, G.; Polito, M.; Piergallina, M.; El Asmar, Z.; Marchetti, M.; Muzzonigro, G. The Role of uroflowmetry biofeedback and biofeedback training of the pelvic floor muscles in the treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections in women with dysfunctional voiding: A randomized controlled prospective study. Urology 2010, 75, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espuña-Pons, M.; Cardozo, L.; Chapple, C.; Sievert, K.; van Kerrebroeck, P.; Kirby, M.G. Overactive bladder symptoms and voiding dysfunction in neurologically normal women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2012, 31, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.-W.; Wu, M.-Y.; Yang, S.S.-D.; Jaw, F.-S.; Chang, S.-J. Comparing the Efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA, Sacral Neuromodulation, and Peripheral Tibial Nerve Stimulation as Third Line Treatment for the Management of Overactive Bladder Symptoms in Adults: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Toxins 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Lindsay, J.; Pakzad, M.; Hamid, R.; Ockrim, J.; Greenwell, T. Botulinum toxin A injection to the external urethral sphincter for voiding dysfunction in females: A tertiary center experience. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2022, 41, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-L.; Chen, S.-F.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Kuo, H.-C. Effect of videourodynamic subtypes on treatment outcomes of female dysfunctional voiding. Int. Urogynecology J. 2022, 33, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-H.; Lee, C.-L.; Chen, S.-F.; Kuo, H.-C. Therapeutic Effects of Urethral Sphincter Botulinum Toxin A Injection on Dysfunctional Voiding with Different Videourodynamic Characteristics in Non-Neurogenic Women. Toxins 2021, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.-M.; Hsiao, S.-M.; Kuo, H.-C. Obstructive patterns in videourodynamic studies predict responses of female dysfunctional voiding treated with or without urethral botulinum toxin injection: A long-term follow-up study. Int. Urogynecology J. 2020, 31, 2557–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, C.; Segura, J.; Osborne, D. Evaluation and treatment of the female urethral syndrome. J. Urol. 1980, 124, 609–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, W.E.; Firlit, C.F.; Schoenberg, H.W. The female urethral syndrome: External sphincter spasm as etiology. J. Urol. 1980, 124, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, S.; Smith, R.B. External sphincter spasticity syndrome in female patients. J. Urol. 1976, 115, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deindl, F.M.; Vodusek, D.B.; Bischoff, C.H.; Hartung, R. Dysfunctional voiding in women: Which muscles are responsible? Br. J. Urol. 1998, 82, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, F., Jr. Nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder (the Hinmann syndrome)—15 years later. J. Urol. 1986, 136, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.C.S.; He, C.; Yao, H.H.; O’Connell, H.E.; Gani, J. Efficacy of sacral neuromodulation and percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of chronic nonobstructive urinary retention: A systematic review. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2021, 40, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, M.; Vottero, M.; Bertapelle, P. Sacral neuromodulation to treat voiding dysfunction in patients with previous pelvic surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: Our centre’s experience. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhang, J.-F.; Kuo, H.-C. Botulinum Toxin A and Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: Pathophysiology and Mechanisms of Action. Toxins 2016, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, L.; Knoepp, L.R. Botulinum Toxin A: A Review of Potential Uses in Treatment of Female Urogenital and Pelvic Floor Disorders. Ochsner J. 2020, 20, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.P.; Nishiguchi, J.; O’leary, M.; Yoshimura, N.; Chancellor, M.B. Single-institution experience in 110 patients with botulinum toxin A injection into bladder or urethra. Urology 2005, 65, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.C. Dysfunctional voiding in women with lower urinary tract symptoms. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2000, 12, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ustinova, E.E.; Fraser, M.O.; Pezzone, M.A. Cross-talk and sensitization of bladder afferent nerves. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010, 29, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, S.; Kawamorita, N.; Oguchi, T.; Funahashi, Y.; Tyagi, P.; Chancellor, M.; Yoshimura, N. Pelvic organ cross-sensitization to enhance bladder and urethral pain behaviors in rats with experimental colitis. Neuroscience 2015, 284, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajbafzadeh, A.-M.; Sharifi-Rad, L.; Ghahestani, S.M.; Ahmadi, H.; Kajbafzadeh, M.; Mahboubi, A.H. Animated biofeedback: An ideal treatment for children with dysfunctional elimination syndrome. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 2379–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-H.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Kuo, H.-C. Therapeutic efficacy of biofeedback pelvic floor muscle exercise in women with dysfunctional voiding. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, B.M.; Fong, E.; Shah, S.; Kelly, C.; Rosenblum, N.; Nitti, V.W. Urodynamic differences between dysfunctional voiding and primary bladder neck obstruction in women. Urology 2012, 80, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, W.; Abrams, P.; Liao, L.; Mattiasson, A.; Pesce, F.; Spangberg, A.; Sterling, A.M.; Zinner, N.R.; van Kerrebroeck, P.; International Continence Society. Good urodynamic practices: Uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.V.; Rome, S.; Nitti, V.W. Dysfunctional voiding in women. J. Urol. 2001, 165, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propert, K.; Mayer, R.; Wang, Y.; Sant, G.; Hanno, P.; Peters, K.; Kusek, J.; Interstitial Cystitis Clinical Trials Group. Responsiveness of symptom scales for interstitial cystitis. Urology 2006, 67, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| VUDS Parameter | Baseline | Post-BoNT-A | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSF (mL) | 124.1 ± 66.6 | 132.9 ± 59.9 | 0.389 |

| FS (mL) | 200.8 ± 90.2 | 212.9 ± 95.8 | 0.334 |

| US (mL) | 241.2 ± 106.1 | 241.2 ± 105.8 | 0.998 |

| Pdet (cmH2O) | 49.4 ± 27.8 | 44.3 ± 30.9 | 0.167 |

| Qmax (mL/s) | 9.2 ± 6.9 | 12.3 ± 7.8 | <0.001 |

| Volume (mL) | 144.8 ± 106.9 | 209.0 ± 121.0 | <0.001 |

| PVR (ml) | 132.9 ± 155.6 | 100.9 ± 109.3 | 0.052 |

| VE | 0.58 ± 0.30 | 0.69 ± 0.27 | 0.002 |

| BOOI | 32.5 ± 31.9 | 26.6 ± 33.7 | 0.104 |

| BCI | 91.7 ± 36.2 | 88.7 ± 43.0 | 0.605 |

| Failure (n = 39) | Successful (n = 27) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BoNT-A injection(s) | |||

| Single injection | 18 (46.2%) | 15 (55.6%) | 0.453 |

| Repeat injections | 21 (53.8%) | 12 (44.4%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 13 (33.3%) | 14 (51.9) | 0.132 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (20.5%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0.606 |

| Coronary artery disease | 4 (10.3%) | 2 (7.4%) | 1.000 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (5.1%) | 2 (7.4%) | 1.000 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1.000 |

| Dementia | 2 (5.1%) | 0 | 0.509 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 (5.1%) | 0 | 0.509 |

| Previous surgeries | |||

| TUI-BN | 9 (23.1%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.332 |

| Spinal surgery | 4 (10.3%) | 3 (11.1%) | 1.000 |

| Pelvic surgery | 6 (15.4%) | 12 (44.4%) | 0.009 |

| VUDS Parameter | Failure (n = 39) | Successful (n = 27) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up period | 9.3 ± 6.7 | 7.7 ± 5.2 | 0.295 |

| Age (years) | 54.4 ± 16.4 | 62.4 ± 13.1 | 0.038 |

| FSF (mL) | 114.3 ± 52.7 | 138.2 ± 81.7 | 0.154 |

| FS (mL) | 192.8 ± 84.3 | 212.4 ± 98.6 | 0.388 |

| US (mL) | 230.1 ± 97.1 | 257.3 ± 117.8 | 0.310 |

| Pdet (cm H2O) | 45.4 ± 27.2 | 55.2 ± 28.2 | 0.164 |

| Qmax (mL/s) | 10.7 ± 7.3 | 7.1 ± 6.0 | 0.038 |

| Volume (mL) | 177.8 ± 116.4 | 97.1 ± 69.0 | 0.002 |

| PVR (mL) | 70.4 ± 99.7 | 223.2 ± 177.9 | <0.001 |

| VE | 0.74 ± 0.23 | 0.35 ± 0.25 | <0.001 |

| BOOI | 27.8 ± 32.0 | 39.3 ± 31.2 | 0.151 |

| BCI | 89.6 ± 35.6 | 94.8 ± 37.4 | 0.569 |

| VUDS DV subtype | |||

| Mid-urethral | 30 (76.9%) | 17 (63.0%) | 0.353 |

| Distal urethral | 7 (17.9%) | 9 (33.3%) | |

| BND | 2 (5.1%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| VUDS Parameter | Failure (n = 39) | p-Value | Successful (n = 27) | p-Value | Δp-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSF (mL) | BL F/U | 114.3 ± 52.7 128.9 ± 53.7 | 0.183 | 138.2 ± 81.7 138.7 ± 68.6 | 0.976 | 0.505 |

| FS (mL) | BL F/U | 192.8 ± 84.3 202.4 ± 86.2 | 0.495 | 212.4 ± 98.6 228.0 ± 108.0 | 0.503 | 0.818 |

| US (mL) | BL F/U | 230.1 ± 97.1 233.3 ± 104.0 | 0.813 | 257.3 ± 117.8 252.5 ± 109.3 | 0.842 | 0.771 |

| Pdet (cm H2O) | BL F/U | 45.4 ± 27.2 42.9 ± 31.2 | 0.633 | 55.2 ± 28.2 46.3 ± 31.0 | 0.079 | 0.394 |

| Qmax (mL/s) | BL F/U | 10.7 ± 7.3 10.9 ± 7.9 | 0.777 | 7.1 ± 6.0 14.4 ± 7.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Volume (mL) | BL F/U | 177.8 ± 116.4 200.0 ± 130.7 | 0.206 | 97.1 ± 69.0 222.1 ± 106.4 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| PVR (mL) | BL F/U | 70.4 ± 99.7 98.1 ± 112.3 | 0.061 | 223.2 ± 117.9 104.9 ± 106.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VE | BL F/U | 0.74 ± 0.23 0.68 ± 0.28 | 0.016 | 0.35 ± 0.25 0.70 ± 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BOOI | BL F/U | 27.8 ± 32.0 27.7 ± 31.5 | 0.990 | 39.3 ± 31.2 24.9 ± 37.3 | 0.002 | 0.050 |

| BCI | BL F/U | 89.6 ± 35.6 81.0 ± 46.3 | 0.265 | 94.8 ± 37.4 99.8 ± 35.6 | 0.571 | 0.248 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Age (years) | 1.037 (1.001–1.075) | 0.043 | 0.990 (0.945–1.038) | 0.687 |

| FSF (mL) | 1.006 (0.998–1.014) | 0.169 | ||

| FS (mL) | 1.002 (0.997–1.008) | 0.384 | ||

| US (mL) | 1.002 (0.998–1.007) | 0.306 | ||

| Pdet (cm H2O) | 1.013 (0.995–1.032) | 0.165 | ||

| Qmax (mL/s) | 0.913 (0.834–0.999) | 0.048 | 1.047 (0.920–1.191) | 0.486 |

| VE | 0.003 (0.000–0.045) | <0.001 | 0.001 (0.000–0.034) | <0.001 |

| BOOI | 1.012 (0.996–1.028) | 0.153 | ||

| BCI | 1.004 (0.990–1.018) | 0.563 | ||

| VUDS DV subtype | 0.365 | |||

| Mid-urethral | Ref. | |||

| Distal urethral | 2.269 (0.716–7.188) | |||

| BND | 0.882 (0.074–10.464) | |||

| Botox injection(s) | 0.453 | |||

| Single injection | Ref. | |||

| Repeat injections | 0.686 (0.256–1.838) | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 2.154 (0.787–5.893) | 0.135 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.356 (0.425–4.325) | 0.607 | ||

| CAD | 0.700 (0.119–4.123) | 0.693 | ||

| CKD | 1.480 (0.195–11.208) | 0.704 | ||

| CVA | 1.462 (0.087–24.430) | 0.792 | ||

| Dementia | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.999 | ||

| CHF | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.999 | ||

| Previous surgeries | ||||

| TUI-BN | 0.417 (0.101–1.711) | 0.224 | ||

| Spinal surgery | 1.094 (0.224–5.334) | 0.912 | ||

| Pelvic surgery | 4.400 (1.387–13.959) | 0.012 | 6.643 (1.223–36.073) | 0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, C.-C.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Kuo, H.-C. Predictive Factors for the Successful Outcome of Urethral Sphincter Injections of Botulinum Toxin A for Non-Neurogenic Dysfunctional Voiding in Women. Toxins 2024, 16, 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16090386

Yang C-C, Jiang Y-H, Kuo H-C. Predictive Factors for the Successful Outcome of Urethral Sphincter Injections of Botulinum Toxin A for Non-Neurogenic Dysfunctional Voiding in Women. Toxins. 2024; 16(9):386. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16090386

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Chia-Cheng, Yuan-Hong Jiang, and Hann-Chorng Kuo. 2024. "Predictive Factors for the Successful Outcome of Urethral Sphincter Injections of Botulinum Toxin A for Non-Neurogenic Dysfunctional Voiding in Women" Toxins 16, no. 9: 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16090386

APA StyleYang, C.-C., Jiang, Y.-H., & Kuo, H.-C. (2024). Predictive Factors for the Successful Outcome of Urethral Sphincter Injections of Botulinum Toxin A for Non-Neurogenic Dysfunctional Voiding in Women. Toxins, 16(9), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16090386